Articles

Late February summitry gave way to stalemate, raising the specter of increased tension on the Korean Peninsula. President Donald Trump and North Korean Chairman Kim Jong Un signaled warmth around their Hanoi meeting – their second summit in a year – but Trump’s walkout hours short of the planned conclusion and the absence of an agreement left everyone struggling to define next steps. South Korea’s surprise at the lack of a deal gave way to efforts at facilitation with calls for inter-Korean economic engagement and President Moon Jae-in’s April visit to Washington. Trump and Moon urged patience and diplomacy and the US and ROK canceled spring military exercises, allowing space for North Korea negotiations. The DPRK still criticized the more limited exercises, announced an end-of-year deadline for the US to change its approach, snubbed South Korea on the first anniversary of the Panmunjom summit, and condemned US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and National Security Advisor John Bolton. Meanwhile, the US and ROK reached an agreement on host nation financial support for US forces stationed in Korea, quieting discord in an otherwise sound alliance.

Breaking down the Hanoi summit

The US and the two Koreas leaned toward the Feb. 27-28 Trump-Kim summit with much fanfare, though Washington and Seoul sought to temper expectations in the immediate run-up to the event, reflective of stumbling blocks that played out. US Special Representative for North Korea Policy Stephen Biegun had laid out the US approach for an agreement that would bring significant economic and other benefits in exchange for denuclearization during his Stanford University address in late January, and South Korean Foreign Minister Kang Kyung-wha had urged real progress in the next round.

US Special Representative for North Korea Biegun remarks on DPRK at Stanford. Photo: Twitter

With the world focused on it, the Hanoi summit started with a dinner among principals, President Trump, his chief of staff and secretary of state on the one side, Chairman Kim, his foreign minister, and party vice chair, the then-envoy Kim Hyok Chol, on the other. The first evening pleasantries, with Kim and Trump expressing satisfaction with the process begun in Singapore, gave way to a more complicated second day, which saw Trump step away from the proceedings two hours prior to the scheduled end, leaving Kim in the lurch.

Importantly, both sides chose to frame the meeting in a positive light, a step forward in a process, despite a lack of final agreement. Many in Washington breathed a sigh of relief, feeling it better that Trump walked away from signing something weak. Kim’s aides, Foreign Minister Ri Yong Ho and Vice Foreign Minister Choe Son Hui, provided an initially negative assessment, but the Hanoi video aired for North Korea’s public focused on the statesmanship of their leader and his relationship with Trump, avoiding any hint of a breakdown. KCNA’s first statement a week later was muted relative to prior denunciations of failed talks, blaming the US but pointing to more positive aspects of the two meetings. Vice Minister Choe followed suit in her condemnation, describing the relationship between Trump and Kim as “miraculous,” while blaming the US for the failure of the talks.

Trump’s initial readout for the press in Hanoi was generally positive, with he and Pompeo describing the progress made relative to the complexity of denuclearization. Trump noted the distraction of Michael Cohen’s testimony on the Hill and pointed to the nuclear and missile test moratorium still in place. He also acknowledged a need for multilateral efforts along with the bilateral talks, crediting the United Nations, South Korea, Japan, China, and Russia as contributors. He twice mentioned contacting President Moon and Prime Minister Abe Shinzo for consultations post-summit, and he rang Moon from Air Force One on departure, reportedly ceding the next steps to Seoul.

The party that bore the initial brunt of the failure was South Korea, whose diplomats scurried to assess a fix and find ways to move forward. In the ensuing weeks, Seoul’s dismay turned to suggestions for a return to talks, economic inducements for North Korea, and preparations for Moon’s visit to Washington.

Much was made of what happened – or failed to happen – in Hanoi. Accusations that North Korea simply wanted the totality of sanctions lifted have been refuted by North Korean officials, who claimed that US demands were all or nothing. Reuters reported in late March that Trump had conveyed a one-page memo to Kim at the table demanding a removal of all nuclear weapons and missiles in exchange for a lifting of sanctions (a la Libya), which Kim promptly dismissed. Regardless, it appears that North Korea failed to have a Plan-B in hand, a sign of North Korea’s limited capacity and of the leader’s youth and relative inexperience.

Saving face

With that in mind, most ensuing actions over the spring can be seen in the light of Kim Jong Un struggling to save face. The return train to Pyongyang was a long ride, but Kim avoided stopping in Beijing along the way. Kim reportedly sidelined his chief envoy, Vice Chairman Kim Yong Chol in late April, although he remains on the powerful State Administrative Council. Also elevated to that body was Vice Minister Choe Son Hui, who joined Foreign Minister Ri Yong Ho in an impromptu press conference in Hanoi, signaling that the diplomats may carry the North forward on its next steps. The condemnation by the North of Pompeo and Bolton should also be seen in that light: we’ve removed our principal interlocutor, you should do the same. That and the show of force with short-range missile tests in late April might also be seen as Kim playing to hardliners after perceived Hanoi failures.

Trump and Kim pose prior to their meeting in Hanoi on Feb. 27. Photo: Reuters

Chairman Kim led North Korea’s party plenary and central committee meetings amid a “tense situation,” largely urging economic self-reliance and condemning those imposing sanctions as “hostile forces,” but refraining from naming the US specifically – creating some wiggle room should the US offer some sanctions relief. Significantly, he also suggested that the US has until the end of 2019 to adopt a new approach or North Korea would pursue a different path – consistent with his New Year’s Day message, where he warned of a timeline for progress. Though Trump and Pompeo did not respond to Kim’s threatened deadline, the announcement portends the return to a harder line of ratcheting tensions.

Face is also an issue for Moon Jae-in, who has staked his presidency on progress with the North. As South Korea’s economy has become more of a concern and political chasms have widened, Moon finds himself in need of a real win. This is particularly true with the end of year in mind, as next year will see Moon – as with all former presidents, who serve a single term – labeled a lame duck. Moon’s polling numbers have declined markedly, and barring improvement with the North, the viability of his approach is in question. Accordingly, aides like special adviser Moon Chung-in have called on the US to allow maximum flexibility, especially in considering a lifting of sanctions for inter-Korean economic development projects.

Mending rifts

President Moon arrived in the United States on April 10 with the goal of kickstarting talks between Washington and Pyongyang. A meeting and lunch with Trump led the two leaders to underscore patience with the process and the need for diplomacy. The week prior to the visit, Moon’s foreign minister and defense chief had laid good ground for a cooperative stance between the allies, and Moon departed with likely the best for which he could have hoped, though critics pointed to a lack of hard results. Pyongyang’s dismissiveness of Seoul’s mediating (“facilitating” as the Moon administration now prefers) role – coupled with failures to show for liaison office meetings in Kaesong and to mark the first anniversary of the Panmunjom summit – represent a further poke in the eye for Moon.

The Moon-Trump meeting came on the heels of an agreement on South Korea’s support for US troops on the peninsula. After an arduous almost year-long process with 10 meetings that failed to bear fruit, the White House brushed aside its demand that Seoul increase support by a time-and-a half – which drew National Assembly concern – and settled on an increase to about $900 million in support for 2019. As had been the case with 2018’s accommodation on the Korea-US (KORUS) Free Trade Agreement, the US and ROK arrived at a compromise, but as was the case in the lead-up to the FTA reinvigoration, Seoul negotiators were concerned, especially given fragility on the security front and the need for strong alliance support in the face of North Korean developments.

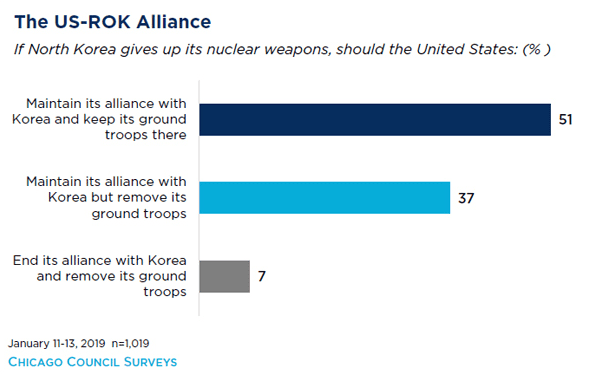

US public support on the troop issue remains strong. Chicago Council on Global Affairs polling shows a full 51 percent of Americans support US troops on the Peninsula, even if North Korea agrees to denuclearize, although 73 percent have doubt about the ability of the US and North Korea to reach agreement. Testimony by new UNC/CFC/USFK Commander Gen. Abrams to the Senate Armed Services Committee continued to emphasize US-ROK readiness and capabilities–though questions about the impact of the drawdown of exercises persist among some observers.

Bar graph depicting US opinion on maintaining its Korea alliance if the DPRK gave up its nuclear weapons. Photo: Twitter

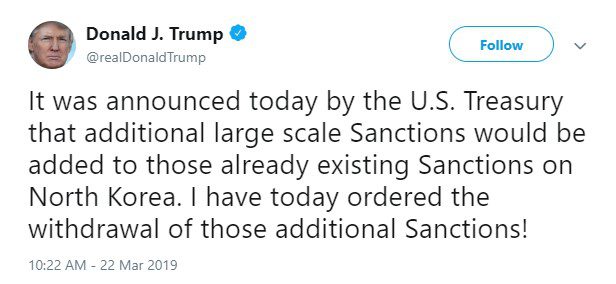

Sanctions confusion and calls for enforcement

Washington’s messaging was not without some inconsistencies. The most noted involved Trump’s purported late March curtailment of massive new sanctions against the North. In fact, the US Treasury Department announced measures against two Chinese shipping companies with more than 60 vessels engaged in sanctions violations. Trump tweeted that he had checked those, leading to some confusion and a rush for clarification. Trump’s efforts appeared to have had the effect of winning a return of North Korean staff to the Kaesong liaison office, after a walkout reportedly ordered at the senior-most level and spurred by the Treasury announcement.

Significant sanction violations were noted in a UN Panel of Experts report released in mid-spring, highlighting violations in shipments of coal, petroleum, and arms, with 20 nations in violation of UN Security Council sanctions. Democrats seized on some of these concerns, as well as human rights and financial violations, and increased calls for greater sanctions enforcement. Concern continued about the treatment that led to student Otto Warmbier’s death, with his parents condemning North Korea as “evil” and lawmakers introducing an act aimed at financial sanctions in his name. Seoul for its part intercepted a Korean vessel on the grounds of violating sanctions, despite persistent criticism from conservative quarters that it has looked the other way too often.

The period saw several efforts to spur new approaches, designed to avoid a return to tensions on the Peninsula. Notable among them were suggestions offered by former USFK/CFC/UNC Commander Gen. Vincent Brooks at Stanford University, Harvard University, and the Korea Society, calling for a “visible but not accessible” international fund aimed at North Korea development. Brooks suggested that North Korea be able to see the movement of funds in light of forward progress on denuclearization, but that it not be permitted access until good efforts were verified. Brooks called for increasing sanctions, while increasing incentives for North Korea at the same time – forcing its hand and encouraging real progress.

President Trump’s March 22 tweet. Photo: Twitter

Reports of site preparations

Several US nonprofit organizations, as well as media outlets in the United States and South Korea, reported at several points on site preparations for rocket or missile launches. Whether it was following a schedule devoid of Hanoi’s input, a post-Hanoi response, or a negotiating tactic aimed at upping the ante, North Korea appeared to be active at Yongbyon with reported sightings of rail cars adjacent to a uranium enrichment area, at the Sohae rocket launch facility, and at a newly reported missile headquarters. The US and ROK governments maintained that the reports from the Center for International and Strategic Studies (CSIS) and elsewhere revealed nothing not already known, as signaled by Trump and Bolton and in Seoul by the National Intelligence Service head, who described the US and ROK as having detailed knowledge of DPRK facilities.

Perhaps the biggest policy disagreement during this period was not between US and Korean policy makers, but rather between President Trump and his intelligence chiefs. Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats testified to the intelligence community consensus that North Korea would not give up the entirety of its nuclear capabilities, a conclusion later underscored by the head of US Indo-Pacific Command. Trump pushed back against that read, breaking with the intel community again, this time in his quest to break new ground with North Korea.

Room for boom

The period ended with North Korea launching a volley of short-range missiles, deemed projectiles by a cautious Washington and Seoul trying together to stem any appearance of a return of North Korea provocation. The all-important moratorium on nuclear and long-range missile tests appeared to be intact, reflecting a calculated move by Pyongyang to push, but only so far. The early May launches followed a mid-April test, directed by Kim Jong Un, of a “new tactical weapon,” a short range guided missile. The White House shrugged off both, projecting calm. Seoul called a meeting of its national security council, but muted its responses beyond urging Pyongyang to refrain from tensions.

Though the latest launches represent a step-up from mid-April and hint at a return to more provocative ways, North Korea appears to be leveraging its threat to return to, rather than refrain from, the negotiation process. Accompanying military moves was condemnation of US Secretary of State Pompeo – with North Korea urging his dismissal from talks – and John Bolton, whose proposals were deemed “dim-witted.” Washington and Seoul refrained from much response to the verbal heat, with Pompeo not taking the bait and reminding North Korea that it is his team in charge going forward.

The US and South Korea showed flexibility and tact in the alliance by moving away from regular, large-scale spring military exercises – Foal Eagle and Key Resolve – and limiting activities to smaller-scale drills, more emphasis on computer-driven command post scenarios, and operations employing fewer forces. North Korea still bristled at the moves, which reportedly drew Kim’s ire, but North Korea no doubt saw the downtick by the US and South Korea as intended: breathing room for the negotiation process. At several other points, US officials urged confidence building and tensions reduction, with Pompeo describing denuclearization as one truncheon alongside a range of efforts at security and peacebuilding.

Looking ahead

For Trump, who enters the US political season later this year and for Moon, who sees an electoral referendum on his approach early next, the clock is ticking. With all sides holding out hope for a resumption of dialogue and Kim Jong Un sending a clear signal that North Korea expects the US to “come up with a courageous decision,” by his yearend deadline, we can anticipate more posturing by all sides in the coming months. In the end, the central problem remains: who goes first?

Jan. 1, 2019: In New Year address, Kim Jong Un says he is ready to meet Trump “at any time” and demands an end to sanctions.

Jan. 10, 2019: President Moon Jae-in calls for “bold steps: ahead of second Trump-Kim summit.

Jan. 17, 2019: President Donald Trump unveils the US Missile Defense Review, which labels North Korea an “extraordinary threat.”

Jan. 17, 2019: Foreign Minister Kang Kyung-wha notes that US and South Korea are discussing “corresponding measures” to reward North Korea for steps toward denuclearization.

Jan. 17-19, 2019: North Korean Special Envoy Kim Yong Chol travels to Washington DC to meet Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Special Representative for North Korea Stephen Biegun to “make progress on the commitments President Trump and Chairman Kim Jong Un made at their summit in Singapore.”

Jan. 18, 2019: ROK and US officials agree to seek a UN Security Council sanctions exemption for inter-Korean joint projects.

Jan. 18, 2019: Trump meets Worker Party Vice Chairman Kim Yong Chol and Special Envoy Kim Hyok Chol at White House.

Jan. 20, 2019: US Special Representative for North Korean Policy Biegun meets Vice Foreign Minister Choe Son Hui in Stockholm.

Jan. 22, 2019: CSIS report describes Sino-ri, one of 20 undeclared ballistic missile bases in North Korea, as a missile headquarters.

Jan 22, 2019: Seoul describes US demands for funding increase for support of US forces in South Korea as “unacceptable.”

Jan 23, 2019: State media reports Kim Jong Un will advance “step by step” and was “satisfied” by recent Washington meetings and a letter from Trump. Secretary of State Pompeo hails “progress” in talks in Washington and Stockholm.

Jan 24, 2019: ROK Foreign Minister Kang calls for “concrete results on denuclearization” at Trump-Kim second summit.

Jan. 28, 2019: US National Security Adviser John Bolton calls on North Korea for a “significant sign of a strategic decision to give up nuclear weapons.”

Jan. 29, 2019: Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats tells Senate Intelligence Committee that “we currently assess North Korea will seek to retain its WMD capability and is unlikely to completely give up its nuclear weapons and production capability.”

Jan. 31, 2019: In comments at Stanford University, Special Representative Biegun notes North and South militaries working with UNC and USFK for confidence building and tension reduction. He notes that the US is willing to wait on key objectives, and that Trump is ready to formally end the Korean War.

Feb. 6, 2019: Special Representative Biegun holds talks in Pyongyang.

Feb. 10, 2019: South Korea agrees to pay $915 million in 2019 for US troops in Korea.

Feb. 12, 2019: US Indo-Pacific Commander Adm. Philip Davidson supports US intelligence community position that North Korea is unlikely to give up all its nuclear weapons or production facilities.

Feb. 15, 2019: Secretary Pompeo says US is hoping to get “far down the road” with North Korea, adding pillars to “reduce tension, reduce military risks” in addition to denuclearization.

Feb. 18, 2019: The Wall Street Journal reports the US is weighing opening a liaison office in North Korea.

Feb. 20, 2019: Trump suggests he expects to meet Kim again after Hanoi and raises prospect of easing North Korea sanctions.

Feb. 21, 2019: Chairmen of the House Foreign Affairs Committee Eliot Engel, Armed Services Committee Adam Smith, and Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence Adam Schiff send letter to Trump urging the White House to stop withholding information on North Korea negotiations.

Feb. 22, 2019: Special Representative Biegun meets DPRK counterpart in Hanoi for a second day of pre-summit negotiations.

Feb. 22, 2019: Trump confirms decreasing US troops in ROK not on summit agenda. White House suggests that if North Korea follows through on denuclearization, the US will explore “how to mobilize for investment, improve infrastructure, enhance food security, and more.”

Feb. 24, 2019: North Korea urges Trump to disregard skeptics.

Feb. 26, 2019: Twenty House Democrats introduce a resolution calling for an end to the Korean War but maintenance of US troops on the Peninsula.

Feb. 27, 2019: Trump hails North Korea’s “awesome” potential and that he is “satisfied” with pace of denuclearization.

Feb. 28, 2019: On second day of Hanoi summit, Trump walks away over reported DPRK sanctions demands. Trump credits China as a “big help” with North Korea.

March 1, 2019: KCNA reports that the US and North Korea “deepened mutual respect and trust” in Hanoi. Kim vows to meet again, Trump says both sides know the issues.

March 1, 2019: President Moon pledges to work with Trump and Kim after failed talks. US and South Korea suggest replacement of spring exercises with smaller drills.

March 3, 2019: Trump says North Korea has no economic future with nuclear weapons.

March 4-12, 2019: US and South Korean militaries hold the inaugural Dong Maeng joint military exercise, a scaled-back version of the annual Foal Eagle and Key Resolve series.

March 5, 2019: Sen. Pat Toomey and Sen. Chris Van Hollen introduce the Otto Warmbier Banking Restrictions Involving North Korea (BRINK) act.

March 5-7, 2019: South Korean Special Representative for Korean Peninsula Peace and Security Affairs Lee Do-hoon visits Washington DC to meet Special Representative Biegun to coordinate plans following the US-DPRK second summit.

March 6, 2019: National Intelligence Service Director Suh Hoon says ROK and US military intelligence has a “detailed grasp” of DPRK uranium enrichment and other nuclear and missile facilities.

March 6, 2019: Seoul calls for a quick resumption of talks after Hanoi breakdown.

March 7, 2019: North Korea Hanoi documentary focuses on Kim-Trump relationship, not summit breakdown.

March 7, 2019: US analysts from 38 North and CSIS’s Beyond Parallel report that North Korea’s Sohae Launch Facility is returning to normal operating status after being moderately dismantled following the Singapore Summit, analysis based on commercial satellite imagery acquired on March 6.

March 8, 2019: North Korea’s Rodong Sinmun reports that the public blames the US for the Hanoi summit ending without agreement.

March 8, 2019: South Korea FM Kang signs Special Measures Agreement with US Ambassador Harry Harris, formally agreeing to pay $915 million for the upkeep of US Forces, Korea.

March 11, 2019: Special Representative Biegun suggests diplomacy is “very much alive,” despite CSIS reports around Sohae rocket testing site.

March 12, 2019: Blue House adviser Moon Ching-in suggests US “all or nothing” approach won’t work with North Korea.

March 12, 2019: UN Panel of Experts reports North Korea sanctions violations by 20 countries in 66-page report.

March 15, 2019: North Korea warns it may suspend nuclear talks, but describes leaders’ relationship as “mysteriously wonderful.”

March 16, 2019: Pompeo says US hopes to continue talks with North Korea.

March 18, 2019: ROK Defense Minister Jeong Kyeong-doo advises a parliamentary defense committee that despite US think tank reports of DPRK launch preparation, “it’s hasty to call it missile-related activity.”

March 22, 2019: Trump blocks new “large-scale” sanctions directed at North Korea, in reality aimed at two Chinese shipping companies in violation of sanctions.

March 25, 2019: North Korean officials return to liaison office after weekend pullout and Trump move to stem new sanctions.

March 26, 2019: South Korean Unification Minister-designate Kim Yeon-chul promises to seek a “creative solution” for the US and North Korea to meet again.

March 26, 2019: Free Joseon, a political organization that opposes Kim Jong Un, claims responsibility for raid on the North Korean Embassy in Spain on Feb. 22. Information stolen from the embassy was later shared with the FBI, but the US government claims no involvement in the operation.

March 27, 2019: UNC/CFC/USFK Commander Gen. Robert Abrams describes North Korean activity as “inconsistent with denuclearization” to House Armed Services Committee.

March 29, 2019: Reuters reports Trump called on Kim to denuclearize completely in one-page Bolton memo delivered at Hanoi. Pompeo meets counterpart Kang Kyung-wha in New York.

March 31, 2019: DPRK describes Spain embassy raid as “grave terrorist attack,” but refrains from blaming the US directly.

April 1, 2019: Moon Jae-in describes hope that North Korea responds positively to US-South Korea efforts in advance of his Washington trip.

April 4, 2019: Former UNC/CFC/USFK Commander Gen. Vincent Brooks calls for a “visible but not accessible” international development fund to promote North Korean denuclearization.

April 4, 2019: South Korea detains a domestic ship over North Korea sanctions violation.

April 10, 2019: DPRK central committee meets amid “tense situation.”

April 10-11, 2019: President Moon travels to Washington DC to meet President Trump for a summit on North Korean diplomacy.

April 12, 2019: Kim Jong Un signals end-of-year deadline for new US stance.

April 13, 2019: Trump calls for a third summit with Kim and hope for a removal of nuclear weapons and sanctions on North Korea.

April 16, 2019: CSIS report reveals April 12 imagery of five specialized rail cars near its Uranium Enrichment Facility and Radiochemistry Laboratory at Yongbyon.

April 17, 2019: North Korea tests new tactical weapon, or a short-range guided missile, and calls for Pompeo to be dropped from talks.

April 19, 2019: Despite North Korean criticism, Pompeo underscores that “it’ll be my team” on North Korea.

April 21, 2019: North Korea dismisses Bolton’s call for denuclearization sign as “dim-witted.”

April 22-May 5, 2019: Air forces of the United States, South Korea, and Australia undertake two weeks of “scaled-back” joint air drills around the Korean Peninsula, replacing the large-scale Max Thunder drill.

April 27, 2019: North Korea accuses US of pressuring South Korea on implementing sanctions.

April 30, 2019: US federal judge orders three Chinese banks to provide documents on a Hong Kong-based front company for North Korea’s nuclear program.

April 30, 2019: North Korea warns of “undesired consequences” if no change in US position.