Articles

US footing on the Korean Peninsula grew less firm as both Koreas resisted moves by Washington. The initial White House call for an increase in annual South Korean host-nation support (HNS) for US Forces in Korea to $5 billion was met with incredulity among the Republic of Korea’s officials and public. By yearend, there were media reports of a lowering of the US ask and agreement by Seoul to arms purchases, but the challenge of finalizing the Special Measures Agreement (SMA) and a residue of resentment remained. Seoul, too, was unhappy with Washington’s lack of progress with Pyongyang, a foil to President Moon Jae-in’s peace ambitions.

North Korea raised its stakes higher, rejecting diplomatic overtures by the United States and its “hostile policy,” disregarding curtailment of US-ROK military exercises, and testing 27 short range ballistic missiles, as well as multiple rocket launchers and engines, between May and the end of the year. December saw activity at the once-decommissioned Sohae Launch Facility. At year’s close, Kim Jong Un declared abandonment of North Korea’s long-range missile and nuclear testing moratorium, expectations of continued sanctions and renewed “self-reliance,” and the promise of a “new strategic weapon.”

The post-Hanoi blues (following the failed US-DPRK summit in February 2019) gave way to malaise around denuclearization talks, despite consistent efforts by the US administration to re-engage in dialogue. North Korea rebuffed overtures by US Special Representative Stephen Biegun, with the exception of one day of talks in Stockholm in October. Those ended with a split in North Korean (bad) and US (good) interpretations, and in retrospect were simply seen by North Korea as an opportunity to deliver its statement on US “hostile policy” and remind the US of its Dec. 31 deadline for progress before Pyongyang pursued a “new path.”

North Korea continued its diplomatic trajectory post-Hanoi, avoiding the US and at the same time distancing itself from South Korea, which had brokered the 2018 opening and righted the faltering US-Korea negotiations in the leadup to the Singapore summit and in the subsequent fall, when Moon visited New York to push for progress at the UN and in US circles for a path to peace. A year on, North Korea failed to turn up for the United Nations General Assembly opening, its UN ambassador speaking on the final day of statements after Foreign Minister Ri Yong Ho stayed home. Kim extended a politely worded apology to Moon on skipping an ASEAN summit in Busan in late November, yet the dye was set, reflecting Pyongyang’s decision to adopt a harder line. That continued with the North’s rejection of Biegun’s overture to meet during his mid-December sojourn in Seoul.

Perhaps by design, Pyongyang’s more insular bent post-Hanoi widened gaps between South Korea and the United States. Moon saw success in establishing dialogue with Kim for both himself and US President Donald Trump, but Trump’s walk away in Hanoi, despite his call after from Air Force One to Moon, was a blow to a South Korean administration bent on dramatically improved inter-Korean relations. By year’s end, Kim pronounced dialogue with the US futile and braced for a long-term struggle, leaving Moon—only months out of what promises to be a hotly contested National Assembly election—in a bind.

The atmosphere between South Korea and the United States was already clouded by Trump’s statements. Since the early days of his administration, the US president had complained about alliances, though at times he praised them, as was the case with NATO. Trump was bruising in his condemnations of European and Asian allies who failed to shoulder sufficient defense burden costs as “freeloaders,” and Seoul planners were particularly susceptible to the insult. This, coupled with broader regional concerns about US reliability and regard for norms and institutions, worries South Korea. On the economic front, the sting created by the Korea-US Free Trade Agreement (KORUS FTA) renegotiations persisted.

Seoul took steps on multiple fronts to negate the impression of unfairly benefitting from US or other largesse. In late October, Seoul acquiesced and abandoned its developing country status in the WTO after White House comments. The debate over defense burden sharing was less easy, fostering new friction in US-South Korea ties.

Host Nation Support

The biggest challenge in the United States-South Korea bilateral relationship this period stemmed from the White House request for $5 billion in South Korea’s annual host-nation support for US troops positioned on the Korean Peninsula. The initial request, which came only months after contentious discussions produced the Feb. 10, 2019 signing of the latest Special Measures Agreement (SMA), caught South Korean officials and the public—as well as many US policy observers—off-guard.

In Seoul, South Koreans rally to denounce U.S. demands for raising costs for stationing troops in South Korea. Photo: The Washington Post

A Korea Institute for National Unification (KINU) poll showed 96% of South Korea’s public opposed paying more. Surprise and resistance to the White House move was exacerbated by the economic decline in South Korea over 2019; exports fell markedly the first 11 months and only declined less in December, suggesting a possible upturn at yearend, as South Korea wrestled with the impact of the US-China trade war and plummeting chip demand.

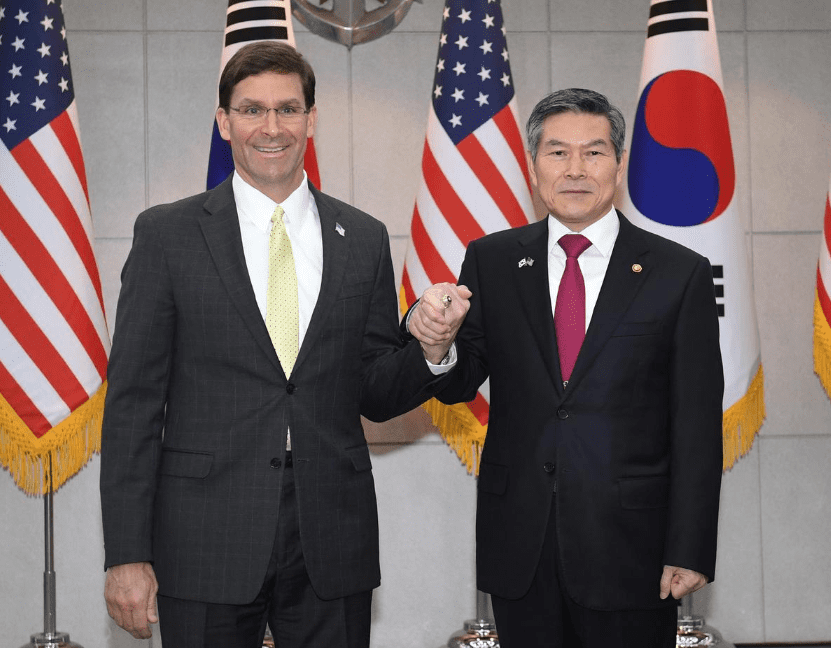

US Defense Secretary Mark Esper traveled to Seoul in mid-November to argue for greater and more “equitable” support, as well as rein in Seoul’s intent to abandon its General Security of Military Information (GSOMIA) pact with Tokyo on Nov. 23. The Republic of Korea had announced it would abandon the military intelligence-sharing pact after a summer of economic sparring between it and Japan—to include the removal, by each, of the other on preferential trade white lists. However, South Korea underestimated the blowback from the United States, which was concerned by the discord when North Korea was stepping up short-range ballistic missile tests and displaying other military advances. Seoul argued that the pact had had limited employment in practice, but Washington believed it was hard won and highly symbolic, and its disintegration a vulnerability benefitting Pyongyang, and by extension Beijing and Moscow.

Mark Esper meets Jeong Kyeong-doo in Seoul on Nov. 15, 2019. Photo: Reuters

Cognizant of US sentiment, Seoul agreed at the last hour to postpone cancellation, quietly hoping that the move would lessen demands at the SMA negotiation table as well. Unfortunately, the initial round of SMA talks broke off with the US lead arguing a lack of ROK commitment to demands for greater equity. By late December, however, Bloomberg and South Korea’s Chosun Ilbo were reporting significant declines in the US request, with suggestions of an increase of between 10% and 20% per annum and possible arms sales. The State Department rebuffed these reports, but expressed hope for an agreement in early 2020.

Critics of the initial ask—both in South Korea and the United States—underscored the need for enhanced transparency in the process. With the proposed budgetary expansion, some observers puzzled at how such a large increase could be spent (or where it came from). Many also questioned the White House timing relative to the shared priority on denuclearization dialogue with North Korea. South Korea may have approached the matter knowing that this US administration makes large initial overtures that would be followed by more reasonable demands, and the inclusion of arms sales and other contributions could provide an offset and allow an offramp to a more practical agreement, one that might best return to a five-year renewal cycle to avoid flareups.

Joint Exercises

Alliance relations involve give-and-take, and a positive and practical reflection on US and South Korea coordination and flexibility centered on the cancelation and postponement of large-scale joint exercises this period. The move aimed to provide room for denuclearization dialogue, and reflected a continuation of cooperation between Seoul and Washington and a preference for diplomacy over force.

However, consistent with its diplomatic hunkering down, North Korea criticized, rather than welcomed, the downtick in joint exercises. More telling, Kim Jong Un twice surveyed North Korean air exercises over three days in mid-November, after the United States and South Korea postponed their combined flying training exercise.

Reflecting a limit to those cancelations, however, the US shared photos with Reuters in late December showing a joint commando exercise simulating a raid aimed at enemy leadership. Secretary Esper and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mark A. Milley also reminded North Korea of the “high state” of US and ROK readiness, despite stated hopes for a return to negotiations. Trump too underscored US resolve, warning on Christmas Eve that in the event of a North Korean provocation, the US would “deal with it.”

North Korean Policy Shift

In his reportedly seven-hour address at the close of late December’s four-day party plenum, Kim voiced a fundamental, strategic shift away from dialogue with the US. His experiment with diplomacy followed North Korea’s last long range ballistic missile test in November 2017 and grew from his 2018 New Year address and the goodwill surrounding the Pyeongchang Olympics.

Two years on, Kim’s December 2019 plenum address—designed first and foremost for domestic consumption and different in form from his shorter, televised past New Year’s addresses—signaled the shift. Although it tacked toward economic change, a buildout of his “economy-first” policy launched in April 2018, it also returned to byeongjin, the simultaneous pursuit of economic development alongside nuclear weapons development.

The underpinning of Kim’s address was disappointment in the experiment of negotiating with the United States. Kim portrayed North Korea’s nuclear and missile moratorium as unilateral and unrequited by the US administration. Although not attacking Trump by name—allowing room for future summits—Kim made clear that the pursuit of dialogue with the United States and sanctions relief was no longer the correct approach. He called for resolve and self-reliance and invoked the lack of progress with the US as an attack on North Korea’s “dignity.” In doing so, Kim reflected the likely need to placate potentially restive voices among elites, some of whom may have wondered at the approach with the US and meetings with Trump, and all of whom were asked to tighten belts.

This watershed shift in North Korea’s position dramatically raises stakes for the United States and South Korea. Kim’s recognition of the futility of dialogue with the United States and subsequent push for military readiness—doubled down on the week prior to the party plenum in a meeting of the party’s Central Military Commission—implied a step up and, more fundamentally, a long term stand against the US.

Critically, also, over time the military is regaining its influence. Though the days of Kim Jong Il’s military-first policy and organization under the National Defense Commission are behind, the emergence of the party’s Central Military Commission as a node of principal influence—albeit party-based and under the State Affairs Commission (SAC)—underscores a harder line in decision-making.

Growing Disregard

Kim Jong Un’s break from recent policy is evident over this reporting period and in retrospect. North Korea’s warning of its self-imposed yearend deadline was voiced by a variety of North Korean officials at several levels. Post-Hanoi, North Korea stepped up its launch of short-range missiles—with all but one taking place after the Trump-Kim meeting at the DMZ. Repeated engine tests—real or implied, took place twice in December at the reactivated Sohae Launch Site, a sign of further hardening of resolve. Worrying are enhancements to the modified Iskander KN-23 short-range missiles and of solid-fuel technology—amplified with potential placement on improved transporter erectors launchers (TELs), and given the Oct. 3 launch of the Pukguksong-3 second-generation submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM).

In diplomacy, the one-day Stockholm talks on Oct. 5 allowed North Korea’s delegation to deliver only a blunt communique. In late November and early December, North Korea issued a flurry of statements from the foreign ministry advisor and vice foreign minister levels, as well as from the SAC—railing in one form or another against Washington’s “hostile policy” and reminding the US of North Korea’s impending deadline.

The name-calling associated with the earlier “fire and fury” phase returned too, with Trump hailing his relationship with Kim multiple times, but referring to Kim as “Rocket Man” in one statement. North Korea in turn invoked the earlier “dotard” label (via Vice Foreign Minister Choe Son Hui) and dismissed Trump as “heedless and erratic” (from Party Vice Chairman Kim Yong Chol); the young leader did not make the comments himself, a hedge against damaging his personal relationship with Trump.

Kim Jong Un for his part took to appearancing atop a white steed at the base of Mount Paektu, the symbolic birthplace of the Korean nation and, by legend, the birthplace of his grandfather, Kim Il Sung. Designed to invoke notions of resistance to foreign/US intervention in the young leader’s domestic audience and change to come, Kim appeared alone in mid-October photos and then with a cadre in support riding behind in early December. Broadcasts of him galloping the slopes also appeared after the plenum address. The images marked the shift in policy and reinforced Kim’s lineage and legitimacy for his elites and public.

Kim Jong Un rides across the snowy Mount Paektu. Photo: Reuters

Conclusion

In his policy shift, Kim may have banked on domestic constraints in 2020 hindering Trump in the US and Moon in South Korea. Arguably, Trump’s distractions over impeachment and election year priorities and the perceived referendum on Moon in the April 15 National Assembly elections may check their attention. But North Korea may misread these constraints as rendering the US administration less potent or cooperation between the White House and Blue House less likely. It is important for Washington and Seoul to get it right, especially at a time of new volatility with Pyongyang.

The US and South Korea must weigh new realities in a clear-eyed manner and prepare contingencies. A satellite test may be in the offing, possibly on or around the February or April birthdays of Kim Jong Il or Kim Il Sung, respectively. That would neatly fit North Korea’s outreach to China and Russia, both of whom have argued for a weakening of international sanctions and would argue a space test is acceptable. Trump too might tack away from a return to fire and fury and explain away a space test as less provocative—though analysts would look hard at any first-stage solid fuel core.

A seventh nuclear test would put North Korea beyond the Indian and Pakistani threshold and might anger Beijing and Moscow, as the international community would unite at the UN Security Council. A blatant long-range ballistic missile test too would cross thresholds and embolden proponents of maximum pressure 2.0.

Trump and Moon will not want to abandon diplomacy and their successes in 2018 and 2019. These include the long-range and nuclear testing moratorium, a return (in the glow of Singapore) of 54 sets of US war remains, and the inter-Korean Comprehensive Military Agreement—which saw the destruction of guardposts and a meeting of Korean troops—along with the highly symbolic leaders’ meetings, three each between Kim and Moon and Kim and Trump.

Kim’s late December shift has led many observers to argue for enhanced ballistic missile defense, civil safety readiness, or a return to US-ROK joint military exercises. Accordingly, the US and South Korea will have to work better together and with Japan—a challenge as the US allies weather significant tension.

Globally, the deterioration of relations between the US and Iran must impact North Korean thinking. The decapitation strike that eliminated Iranian major general Qasem Soleimani and concern about Trump’s volatility could check Pyongyang’s instinct to experiment, yet widespread international concern and condemnation and the initial, quick de-escalation of tensions might falsely embolden North Korea’s young leader.

The US and ROK must engage in better ways at understanding one another’s core strategic objectives—eliminating the clear and present danger of North Korea’s nuclear threat for the one and a stable integration and ultimate unification for the other. So too, Washington needs to more fully incorporate an understanding of Korea’s domestic political realities and constraints. Moon is a progressive president who tacks left, yet underscores backing US priorities. He faces opposition from the right, albeit divided, but also pulls from the left and civic, church, provincial, and municipal entities—all of which make for difficult politics. The complexity of the political divide in South Korea is profound, as are domestic divisions in Washington. These often temper policymakers’ better instincts; therein lies a fundamental challenge to maximizing relations between the US and South Korea.

Sept. 1, 2019: North Korea says its hopes for more dialogue with the White House are “gradually disappearing,” and threatens to reconsider its conciliatory gestures.

Sept. 4, 2019: North Korea tells the UN to cut its international staff given undue US influence.

Sept. 6, 2019: US Special Representative Stephen Biegun confirms that denuclearization talks have stalled.

Sept. 9, 2019: North Korea says it is willing to resume talks late month, but calls for a new US approach.

Sept. 9, 2019: North Korea fires missiles despite moves to restart talks with the US.

Sept. 10, 2019: North Korea’s state-run Korean Central News Agency (KCNA) reports a test of a “super-large” multiple rocket launcher.

Sept. 13, 2019: US sanctions three North Korean state-sponsored groups linked to hacking and high-profile ransomware attacks.

Sept. 15, 2019: North Korean leader Kim Jong Un reportedly invites US President Donald Trump to visit Pyongyang, according to South Korea’s Joongang Ilbo.

Sept. 16, 2019: Trump says he “probably” won’t visit Pyongyang for a next round of talks with Kim, but might in the future.

Sept. 20, 2019: Bolton contends that Trump’s courtship of Kim is increasing North Korea’s power.

Sept. 20, 2019: North Korea praises Trump’s “wise political decision” to fire National Security Adviser John Bolton.

Sept. 26, 2019: KCNA reports that a lack of US progress casts doubt on future talks.

Sept. 27, 2019: North Korea urges Trump to adopt a bold move toward reviving diplomacy.

Oct. 1, 2019: KCNA announces working-level talks with the US within a week.

Oct. 3, 2019: North Korea announces a submarine-launched ballistic missile test, though with Kim absent during testing.

Oct. 5, 2019: The United States and North Korea hold working-level talks in Stockholm.

Oct. 5, 2019: North Korea describes the US as having arrived at the talks “empty-handed,” although the US dismissed the assertion as not reflecting the “content or spirit” of the dialogue.

Oct. 16, 2019: Kim rides a white horse on Mt. Paektu, revered as the birthplace of the Korean nation, symbolizing resistance to the US and a significant move in the near future.

Oct. 17, 2019: Bolton writes in a letter to his political action committee that North Korea “isn’t our friend and will never be” and that they will “never give up their nuclear weapons. Period.”

Oct. 19, 2019: South Korean students break into the US ambassador’s residence in protest over increased host-nation support.

Oct. 21, 2019: North Korea asks for new US and South Korea solutions for conflict. The US wins a court battle over control of a North Korean cargo ship used to skirt sanctions.

Oct. 25, 2019: South Korea abandons its status as a developing country in the WTO after Trump criticism.

Oct. 28, 2019: North Korean Central Committee Vice Chair Kim Yong Chol warns that the good relationship between Kim and Trump is no guarantee that tensions will not flare and that an exchange of fire could happen at any time.

Nov. 1, 2019: North Korea tests a “super-large” multiple rocket launcher and short-range missiles, marking a dozen different tests since May.

Nov. 3, 2019: South Korea and the US suspend an air-power drill for a second straight year.

Nov. 4, 2019: A South Korean parliamentarian suggests North Korea and the US will resume talks in mid-November.

Nov. 8, 2019: North Korea says the “window of opportunity” for talks with the US is closing.

Nov. 9, 2019: South Korea reiterates its intent to terminate its intelligence-sharing pact with Japan, raising concerns in Washington.

Nov. 13, 2019: North Korea warns of retaliation over reduced—but not ended—US and South Korea military drills.

Nov. 14, 2019: Esper arrives in Seoul, with an eye to alliance management with Korea and Japan in general, and host-nation support talks in particular.

Nov. 15, 2019: Esper presses Seoul to pay more for US troops and maintain its intelligence-sharing pact with Japan.

Nov. 17, 2019: The US and South Korea postpone joint Combined Flying Training event to allow for diplomacy with North Korea.

Nov. 18, 2019: South Korea and the US resume talks over US demands for enhanced host-nation support.

Nov. 18, 2019: Kim supervises air force drills for the second time in three days despite US and South Korea’s postponement of drills.

Nov. 19, 2019: US walks out of military cost-sharing talks with South Korea; lead negotiator James DeHart describes South Korea as “not responsive to our request for fair and equitable burden-sharing.”

Nov. 20, 2019: Biegun suggests Kim hasn’t empowered his negotiators to engage seriously in talks.

Nov. 20, 2019: Esper denies reports of a US threat to cut troops over host-nation support.

Nov. 22, 2019: South Korea backs away from scrapping its intelligence-sharing pact with Japan after US pressure.

Nov. 23, 2019: South Korea asks US for help in resolving issues with Japan.

Nov. 28, 2019: North Korea test fires two ballistic missiles on the US Thanksgiving holiday and a day ahead of the two-year anniversary of its long-range missile and nuclear testing moratorium.

Nov. 29, 2019: FBI arrests US blockchain expert who aided North Korea.

Dec. 3, 2019: North Korean Vice Foreign Minister Ri Thae Song described the US as dragging out talks and warns that that it is “entirely up to the US what Christmas gift it will select to get.”

Dec. 3, 2019: Trump states confidence in Kim, but also describes him as “Rocket Man.”

Dec. 4, 2019: Kim appears atop a white horse at Mt. Paektu, with cadre fallowing, hinting at a more confrontational stance moving forward.

Dec. 5, 2019: Commercial satellite imagery shows movement at North Korea’s Sohae Launch Facility, and Vice Foreign Minister Choe Son Hui warns against the “relapse of the dotage of a dotard” in Trump.

Dec. 6, 2019: US Ambassador to the UN Kelly Craft warns that the Security Council is united against North Korea’s repeated missile tests. In a nod to diplomacy, US withholds support for a North Korea human rights debate at the UN.

Dec. 7, 2019: Trump and Moon speak by phone and underscore that talks with North Korea should continue. North Korea says it carried out a “very important test” at Sohae.

Dec. 8, 2019: North Korea’s UN Ambassador Kim Song says denuclearization is off the negotiating table with the US.

Dec. 10, 2019: Secretary of State Mike Pompeo says he is “very hopeful” North Korea will abide by its commitments. North Korea lashes out at Pompeo and his calls for sanctions enforcement.

Dec. 11, 2019: Craft says the US is prepared to “simultaneously take concrete steps” with North Korea, but that the United Nations Security Council must respond to provocations.

Dec. 12, 2019: US Assistant Secretary of State David Stilwell cautions North Korea against “ill-advised behavior” and notes that the US has “heard threats before.”

Dec. 14, 2019: North Korea says its undertook a “crucial” test at Sohae the day before.

Dec. 15, 2019: Biegun arrives in South Korea for a three-day visit, urging North Korea to drop its “hostile” tone and return to nuclear talks.

Dec. 16, 2019: Esper suggests North Korea will test if it doesn’t “feel satisfied.”

Dec. 20, 2019: Esper says he is hopeful for a restart of diplomacy with North Korea, although he and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Milley also describe the US “high levels of readiness.”

Dec. 21, 2019: North Korea criticizes the US for targeting its human-rights record and warns it will “pay dearly.” Kim Jong Un convenes a meeting of the Central Military Commission.

Dec. 23, 2019: Bolton laments Trump’s “failure” on North Korea.

Dec. 23, 2019: US provides Reuters with photos of US and ROK commandos simulating a raid on an enemy facility.

Dec. 23, 2019: The US and its allies call on UN members to report compliance on returning North Korean workers.

Dec. 24, 2019: Trump says if North Korea tests an ICBM, the US will “deal with it.”

Dec. 25, 2019: Media report that the US is backing down from its demand for a five-fold increase in host-nation support.

Dec. 27, 2019: US denies reports that it asked South Korea to pay 10% to 20% more for US troops.

Dec. 29, 2019: National Security Adviser Robert O’Brien says the US would be “extremely disappointed” should Kim resume testing and will “demonstrate” that disappointment.

Dec. 30, 2019: Kim calls for North Korea’s “positive and offensive security measures” at a year-end party plenum.

Dec. 30, 2019: Microsoft Corp. says it has taken control of 50 web domains used as a “command and control infrastructure” by North Korean hacking group Thallium to steal information.

Dec. 31, 2019: KCNA reports that Kim said North Korea is no longer bound by its moratorium on nuclear and long-range missile tests. Kim suggests a “new strategic weapon” will be unveiled in the near future.