Articles

In the last four months of 2019, Beijing and Moscow continued to broaden and deepen their strategic partnership across political, economic, diplomatic, and security areas with some visible outcomes: the 3,000-km, 38-bcm “Power of Siberia” gas line went into operation and the cross-border rail and road bridges were finally completed after decades of endless negotiations and delays. While Chinese and Russian top leaders jointly steered the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and BRICS through challenging times, it was in military relations that breakthroughs were made.

This included Russia’s assistance in the construction of a missile attack early-warning system for China, China’s participation in Russia’s Center-2019 large-scale exercises, and the first joint naval exercises with Iran in the last few days of 2019. These developments took place amid continuous discussion on both sides about the nature, scope, and degree of an “alliance” relationship, formal or not, in an increasingly fluid and challenging world. With the rapidly deteriorating Iran-US relations at the onset of the new decade, it remains to be seen how Moscow and Beijing can keep their “best ever” relationship short of moving to a formal alliance, a state of affairs they have been trying to avoid for years.

24th Prime Ministerial Meeting in St Petersburg

All high-level interactions between Chinese and Russian leaders in the last few months of 2019 were annual regular meetings either in bilateral or multilateral formats (the SCO and BRICS). On Sept. 16-19, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang traveled to Russia for the 24th Prime Ministers’ Regular Meeting with his Russian counterpart Dmitry Medvedev in St. Petersburg. The meeting covered a wide range of issues, from trade, investment, market access, and settlement of payment in local currencies, to anti-trust, intellectual property rights, the agricultural/food industry, cross-border transportation, manufacture cooperation, regional development, digital commerce, custom service, environment and sustainable development, science, and humanitarian exchanges. In Medvedev’s words, the two prime ministers covered “practically all areas.”

They also agreed to cooperate in multilateral forums such as the UN, WTO, APEC, G20, SCO, BRICS, and the regional projects of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and EAEU (Eurasian Economic Union), which were very important “in the current uncertain political and economic global situation, with many factors of instability,” Li said.

Twenty-four documents were signed at the end of the meeting, including a five-year trade plan, cooperation in agriculture, energy, border inspection, and several investment projects in Russia’s Far East, the Arctic, joint ventures, etc.

Medvedev thanked the Chinese for their “constructive work and friendly attitude” during the meeting. He particularly noted progress in research and space cooperation. Li echoed his Russian host, saying that the two sides were “willing” and “ready” to strengthen cooperation in basic and applied research. Several agreements were signed during the meeting, including a joint data center for the exploration of the moon and deep space, joint construction and operation of a fast neutron reactor in China, a $1 billion joint research and technology innovation fund, compatibility and interoperability of BeiDou (北斗) and GLONASS (ГЛОНАСС) global satellite navigation systems, and IT and AI development. The two sides will launch the “Scientific and Innovation Cooperation Years,” in 2020-21. “The two countries need to take this opportunity to upgrade their scientific and technological innovation cooperation,” Li told reporters.

Following the St. Petersburg meeting, Li traveled to Moscow on Sept. 18 and met Russian President Vladimir Putin in the Kremlin. Referring to the 70th anniversary of Russia-Chin diplomatic relations, Putin noted that “a very long distance has been covered in the history of bilateral cooperation over the past decades. Today, we really are strategic partners in the full sense of the word, and are implementing a comprehensive partnership that remains Russia’s unconditional foreign policy priority.” Li responded by saying “[I]ndeed, we have come a long way – we have been holding regular meetings without fail for 20 years, and the agenda is continuously being filled with new content.”

Bridges Too Far?

The “long-distance” may be a convenient phrase to capture the twists and turns of the 70 years of Sino-Russian relations. In bilateral economic ties, however, the “long distance” fits well. At the end of 2019, both Putin and Li indeed had reasons to breathe easy as several marathon-like joint projects were completed after years, and even decades, of hibernation.

On Nov. 29, the first vehicle bridge across the Amur River between Russia and China was finally finished, 24 years after the two countries signed an agreement in 1995. Construction, however, did not start until the end of 2016. Still, people and their cars in the Russian city Blagoveshchensk (Благовещенск) and Chinese city Heihe (黑河) will have to wait until mid-2021 for the bridge to open for traffic.

Blagoveshchensk, Russia. Photo: Google Maps

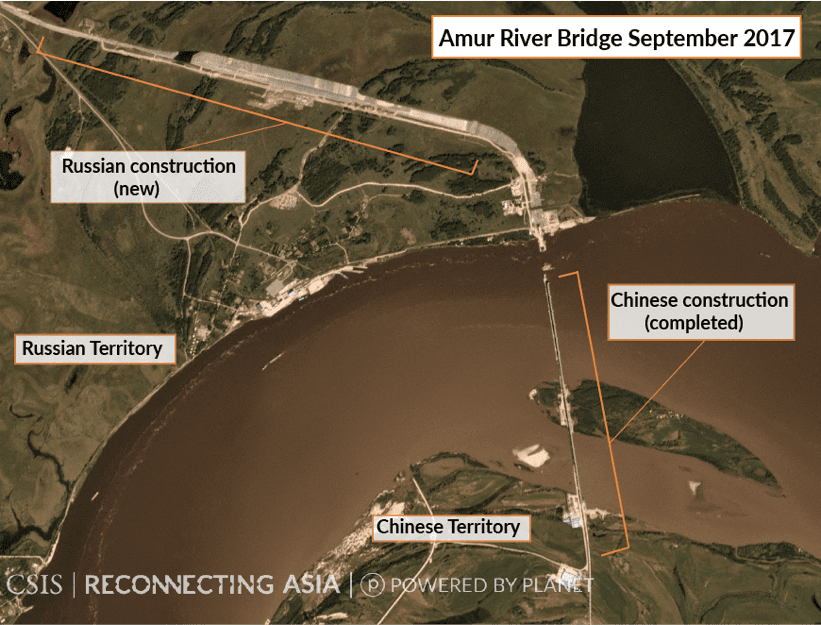

Located 450 km downstream from the Amur to the southeast, the first Russia-China rail bridge took just 12 years, or half of the time, of the Blagoveshchensk-Heihe road bridge. First proposed by Russia in 2007, the 2,200-meter rail bridge between Russia’s Nizhneleninskoye (Нижнеленинское) and Chinese city Tongjiang (同江), did not complete its structural link until March 2019. Putin’s visit to China in May 2014 led to an agreement for construction to start later that year. The Chinese completed their side of the work in July 2016 while the Russian side had just started at that time. It looks like construction of both bridges received fresh impetus after the 2014 Ukraine-Crimea crises, when Russia was sanctioned by the West.

Amur River Bridge. Photo: CSIS Reconnecting Asia

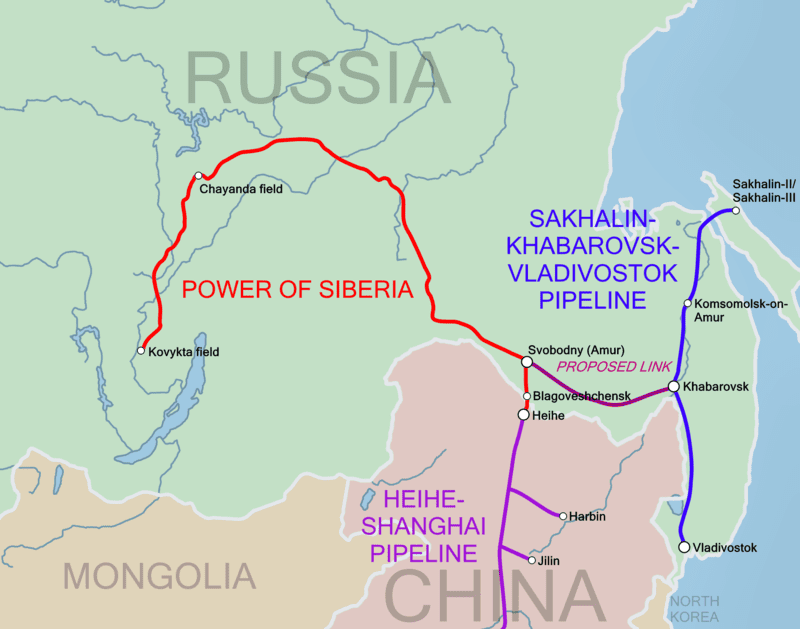

The same was true for the 8,000-km “Power of Siberia” (Сила Сибири) gas line, also known as “China–Russia East-Route Natural Gas Pipeline,” which started to deliver gas on Dec. 2, 2019. Its construction started in September 2014, or 20 years after the two sides signed a memo in 1994. For its historic inauguration, Presidents Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin presided over the opening ceremony on Dec. 2 by video. The $400 billion pipeline, with an annual capacity of 380 billion cubic meters (bcm) of gas to China for 30 years, will considerably alleviate China’s thirst for clean energy. In 2017 and 2018, China became the world’s largest importer of oil (440 million tons) and gas (125.4 bcm), respectively.

Russian pipeline routes and the proposed link between them. Photo: Wikipedia

SCO in Tashkent: The Unity of Differences?

The SCO held its 18th Prime Ministerial Meeting in Tashkent, Uzbekistan on Nov. 2. Chinese Premier Li Keqiang and Russian Prime Minister Medvedev joined the meeting of the SCO heads of the government. They also met prior to the SCO formal meeting. From Tashkent, Li and Medvedev also traveled to Bangkok on Nov. 4 for the 14th East Asian Summit.

There was a keen awareness in Tashkent of the changing and challenging external environment for the regional organization: be it protectionism, trade wars or sanctions. “This certainly does not make our work easier,” said Medvedev. “Complex and deep changes are taking place in the world with visibly increased elements of instability and uncertainty,” echoed Li. Given these external challenges, the prime ministers focused on institutional development, primarily in economics and humanitarian cooperation. All participants believed the SCO should prioritize improving living standards, to be achieved through sustainable development and cooperation in the areas of infrastructure, trade, finance, digitalization, energy, environment, and humanitarian exchanges. Fourteen documents were inked in Tashkent, including a 15-year outline for multilateral economic cooperation, a railroad coordination memo, and cooperation agreements for rural digitalization, agriculture and food, the environment, etc.

Additionally, heads of the government proposed to create in the near future more expert working groups (EWG) for industry, energy, and regional development. Currently, EWGs have been established only for certain “high politics” issue areas such as defense and information security. Some of the most discussed issues were in the social (youth and women), cultural, educational, tourism, and sports. The Chinese premier offered a list of specific events, including hosting an SCO craftsmen workshop, a vocational skills contest and SCO forum on traditional medicine in China, organizing training programs for poverty eradication, and providing 1,000 free cataract surgeries for SCO members and observers over the next three years through the Lifeline Express International Sight Saving Mission.

The Tashkent meeting was overshadowed by the Indian-Pakistani border conflicts that started in February when a suicide attack in India-held Kashmir led to both ground and air operations by the two sides. In August, India revoked the special status granted to Jammu and Kashmir on Aug. 5, leading to further tension in the region. The renewed India-Pakistan conflict was the first between SCO member states, whose predecessor, the Shanghai Five, started in post-Soviet times as a mechanism to handle border issues. Successful resolution of border issues between members helped gave rise to the SCO in 2001. Since then, the SCO has focused on consensus building and avoided becoming a platform for conflict resolution between any of its members. This operational principle of the SCO worked this time as the heads of state in Tashkent focused on issues concerning the group rather than the largely unresolvable India-Pakistan conflict.

BRICS’ 11th Summit

If the SCO remains a regional enterprise for Russia and China, BRICS adds a global dimension (Brazil and South Africa). At almost all times, Chinese and Russian leaders seized opportunities for a mini-summit on its sidelines. During the 11th BRICS summit on Nov. 14 in Brasilia, the Chinese and Russian presidents met on the sidelines prior to the summit. Xi emphasized the importance of the 70th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic ties and the elevation of the bilateral ties to a historic new height (“China-Russia comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination for a new era”); and he was looking forward to the coming “China-Russia year of scientific and technological innovation from 2020 to 2021.”

Putin defined Russia-China relations as “profound friendship and mutual trust” that is “unaffected by any external factors.” In addition to “close political coordination, mutually beneficial economic cooperation and close coordination on international stage,” Putin added that “a lot of work is being done in terms of our military-technical cooperation and military interaction in general. This is truly a comprehensive partnership.”

For Russia and China, BRICS was to be sustained, and even expanded for a variety of reasons, particularly in the midst of the fragmentation of existing multilateral platforms such as the WTO, as well as those designed to address climate change, arms control, etc. Russia is chairing BRICS from January 1, 2020 with a more expansive theme: “Partnership for Global Stability, Shared Security and Innovative Growth.” In Brasilia, Putin revealed that Russia would seek more coordination between BRICS members in several key areas: more coordination in foreign policy, primarily at the UN for peacekeeping and anti-terrorism; a joint statement for the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II; updating BRICS’ “Strategy for BRICS Partnership in Trade and Investment” for the next five years. Some 150 events would be held under the Russian chairmanship, which would culminate in the next summit in St Petersburg, where EAEU states and Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) members would join the BRICS summit.

While Putin planned to maximize the future of the BRICS at the Russian helm, Xi focused on the present: mending fences with the South American giant and stimulating BRICS’ investment projects. A few months into the Brazilian presidency in 2019, the far-right former army captain Bolsonaro became more conciliatory regarding economic relations with China, Brazil’s largest trading partner. In official talks prior to the BRICS summit, the Chinese and Brazilian presidents further committed their two countries to mutual market liberalization and cooperation in trade, energy, minerals, science and technology, and investment, following Bolsonaro’s successful visit to China in late October. Already, two-way trade volume between China and Brazil (more than $112 billion in 2018) had surpassed that of Sino-Russian trade, and Brazil exported twice as much to China as to the US. A successful BRICS summit would not be possible without a reasonably solid foundation with the host.

For Xi, the existence and continuity of BRICS itself was a useful counterforce to the international anti-globalization trend, such as “rising protectionism and unilateralism; greater deficit of governance, development and trust; and growing uncertainties and destabilizing factors in the world economy,” Xi said in his official remarks at the summit. Xi’s concerns were set against the backdrop of a trade war with the US since early 2018. At the heart of the China-US trade disputes was science and technology. BRICS’ response was to launch its “Partnership on New Industrial Revolution (PartNIR)” in its Johannesburg summit in July 2018. The goal was to cooperate and coordinate in “digitalization, industrialization, innovation, inclusiveness and investment.”

For Xi, BRICS served as an integral part of China’s effort to build “a community with a shared future for mankind” (人类命运共同体). In comparison, Russia’s strategy regarding BRICS seemed to use the platform to integrate those multilateral forums led by Russia, such as EAEU, CIS, etc. Both, however, required a sustainable and growing BRICS in the midst of an increasingly fragmented world.

Deepening Military-to-Military Ties

The last four months of 2019 witnessed much active mil-mil interaction between China and Russia. Four joint exercises were held, including a conventional large-scale land-based drill (Center-2019 in September), an anti-terror drill (Cooperation 2019 in October) and two naval drills (with South Africa in November and with Iran at the year-end).

From Sept. 16-21, 2019, the Russian military conducted its Center-2019 (Центр-2019) military exercises in eight training areas in the Orenburg, Astrakhan, Chelyabinsk, Kurgan, Altai, and Kemerovo Regions for almost 130,000 soldiers, 20,000 pieces of equipment, 600 aircraft, and 15 warships. It was a considerably larger drill than Center-2015 when 95,000 troops and 7,000 pieces of hardware were involved. Center-2019 was defined as an antiterrorist drill. The scale, duration and scenario, however, were typical of conventional warfare, such as active defense, massive bombing, as well as offensive and consolidation operations.

China sent 1,600 troops, 300 pieces of equipment, and 30 aircraft, together with 750 men from Pakistan, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. This was the second time China had joined Russia’s large-scale exercises following Russia’s “East-2018” (Восток 2018) exercises.

Until 2018, exercises by Russian military districts only invited some CIS members such as Belarus and Kazakhstan. China’s participation in large maneuvers inside Russia indicated a major upgrading of mil-mil relations with Russia. Although the number of Chinese military personnel involved was less than half of that for the East-2018 maneuvers (3,500), the momentum seemed to point to a more regular participation in those maneuvers rotating between Russia’s four military districts. It remains to be seen if the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) will join Russia’s scheduled drills of the Western and Southern Military Districts in the next two years.

Russia’s military districts. Photo: Google

The increased frequency of China-Russia joint exercises was accompanied by a more expanded scope of these drills. For the first time, the Russian and Chinese navies joined the third parties: South Africa and Iran. While the former is a member of the BRICS, the latter is an SCO observer state (along with Afghanistan, Belarus, and Mongolia), a status below formal membership but above “dialogue partner” (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Cambodia, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Turkey).

In September, Moscow, Beijing, and Tehran announced that a joint naval exercise would be held in the last four days of 2019 in the northern part of the Indian Ocean and Gulf of Oman. Between Dec. 27 and 30, three Russian vessels and one Chinese guided missile destroyer (Xining, 西宁) joined the Iranian naval forces for anti-piracy, communication, and night navigation exercises. The trilateral maneuvers occurred at a sensitive time and place, with rising tension in the region after the Trump administration pulled out of the Iranian nuclear deal in May 2018. The decision was made in the aftermath of US-initiated “International Maritime Security Construct” (IMSC, which includes the UK, Australia, Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Bahrain) to patrol the Gulf of Oman, the Persian Gulf and the Strait of Hormuz waterway, a transit point for a fifth of the world’s oil exports.

Prior to this first-ever naval maneuver between the three navies, Iran had had separate bilateral exercises with Russia and China. Unlike the US and Russia, China’s footprint in the Middle East has been quite insignificant despite its growing economic clout in the region. As the world’s largest oil importer, 43% of China’s oil imports goes through the Strait of Hormuz. For the sake of its own energy security, China is perhaps the only major power that has been “aloof” in the highly sensitive region while managing to maintain good working relations with virtually all regional players (Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, Syria, etc.), including American allies. This may explain the relatively low visibility of the drill in China’s media. Shortly before the exercises, Chinese Defense Ministry defined the drills as normal military exchange activities that had no connection with regional tension (与地区形势没有必然联系).

More coordinated efforts were also made at the multilateral level. Twice in the last four months of 2019, the Expert Working Group (EWG) affiliated with the Meeting of Defense Ministers of the SCO met first in Moscow (the 7th meeting) on Oct. 31-Nov. 1, and then in Beijing (the 8th meeting) on Dec. 9. In addition to discussing normal SCO issues such as antiterrorism, Moscow intended to combine the next SCO defense chiefs meeting with those of the CIS and the CSTO, scheduled for June 2020 in Moscow.

One of the highlights of close Sino-Russian mil-mil ties was the first presence of Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu at the 9th Beijing Xiangshan Forum (香山论坛) on Oct. 20-22. Since its inception in 2006 as a track-2 platform for Asia-Pacific security dialogue by the China Association of Military Science (CAMS) and the China Institute for International Strategic Studies, the forum has become an important platform for dialogue and cooperation on defense and security issues, at both the regional and global levels.

Shoigu’s presence was a highlight of the Chinese security forum as his speech was prominently featured right after the speech by Chinese Defense Minister Wei Fenghe. One of the key points of Wei’s keynote speech was China’s commitment to building a new type of security partnership. Wei cited China’s military relations with Russia as a model and such a relationship enjoyed “the highest level of mutual trust, strategic coordination and practical cooperation, and maintains a vigorous momentum of development. It is a model of security cooperation and an important cornerstone underpinning world peace.”

Shoigu echoed this by saying that the China-Russia “military cooperation has played an important role in the mutually beneficial ties of China and Russia.” Meanwhile, his speech criticized three major aspects of US foreign and security policies. First, he warned that “Chaos and the collapse of statehood are becoming the norm,” and “it is enough to recall Yugoslavia, Iraq and Libya, against which military force was used under contrived pretexts and bypassing the decisions of the UN Security Council. Today we are witnessing an attempt at a violent change of power in Venezuela.”

Regarding the INF treaty, Shoigu criticized US withdrawal in that “the real reason that prompted Washington to unilaterally withdraw from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) is the deterrence of the People’s Republic of China and the Russian Federation,” he added.

Russian Defence Minister General of the Army Sergei Shoigu speaks at the 9th Beijing Xiangshan Forum. Photo: Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation

He concluded by questioning the US Indo-Pacific strategy, which did not have a clear geographic explanation and does not include all countries in the region. “We believe that the artificial expansion of the sphere of cooperation to the so-called Indo-Pacific region is aimed at creating dividing lines, clashing the Asia-Pacific countries and, ultimately, at restraining regional development,” stated Shoigu.

Putin’s “Big Secret”

Efforts to enhance mil-mil ties also came from the highest level of Russian leadership. In his speech to the 16th Valdai Forum in Sochi of Russia on Oct. 3, Putin surprised the audience by revealing “a big secret,” that Russia is helping China create a missile attack early-warning system (система предупреждения о ракетном нападении). “This is very important and will drastically increase China’s defense capability. Only the United States and Russia have such a system now,” he added. The Russian president did not offer any further details regarding the location, specifications, and funding of an early-warning system for China.

Responding to a Japanese reporter’s question at his annual year-end press conference on Dec. 19, Putin said that he believed that China was capable of creating a missile early warning system on its own, but “there are certain projects that take up a great deal of time to implement,” and “with our help, it will do this faster,” said Putin. He further emphasized the defensive nature of the early warning system: “This is a missile early warning radar system, which means the system works when you are being attacked…I would like to repeat that this system does not encourage aggression and is intended to protect one’s own territory,” insisted Putin. An early warning system allows China to adopt a launch-on-warning posture instead of waiting for enemy missiles to explode on its territory. China’s small nuclear arsenal, therefore, would become more survivable, hence a more credible deterrent against potential adversaries.

There was no solid information about the origin and process of this joint early warning system. Media sources argued that Russia took the initial step in May 2015 by suggesting that Russia was “willing” to build a ballistic missile defense system for China. In the next two years, Russia and China conducted two missile defense computer simulations code-named “Aerospace Security” in May 2016 and December 2017. Since April 2019, the two sides have been preparing for the third simulation. Russia’s early warning system apparently impressed the Chinese side during those simulations.

In late 2018 and early 2019 when Russia and China were preparing for the third simulation, global strategic stability was in disarray, as the US was readying itself to withdraw from the INF Treaty, which became official on Aug. 2, 2019. The end of the INF meant more deployment of US short and intermedium-range missiles around China’s periphery. The combined effect of these developments in both bilateral and trilateral levels presumably made China reach out to Russia, according to Dmitry Trenin, director of the Carnegie Moscow Center.

Putin justified the disclosure of the early-warning system for China because “it will transpire sooner or later anyway.” It also reflected a pattern in the Sino-Russian reciprocity in which Moscow became more eager for closer mil-mil ties with Beijing, particularly after the 2014 Ukraine crisis. In 2017, Russia initiated a three-year road map for mil-mil cooperation with China, which apparently included “the full-fledged expansion of cooperation to cover strategic arms,” according to Vasily Kashin, a Moscow-based expert on military-strategic affairs.

Even so, China’s reaction to Putin’s revelation was somewhat reserved. In mid-October 2019, China’s Ambassador to Moscow Zhang Hanhui stressed the “defensive nature” of such a system. Meanwhile, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Geng Shuang described the system as part of the “normal” exchange and cooperation, and did not target any third party.

Assessment of Putin’s revelation was quite different, reflecting the asymmetrical capability of the two sides in the area of missile defense. Military experts in Beijing accredited Russia’s claim with its long operational experience in early-warning system dating back to the Cold War, according to Yang Yucai, professor of the PLA’s National Defense University. Russia even “enjoys ideal geographical conditions to develop an anti-missile system,” added Yang. He went as far as to say that Russia may even assist China in developing a missile defense (MD) system, in addition to an early-warning system.

The timing of Putin’s remarks “reflected the fact that Beijing and Moscow have been deepening political trust and cooperation,” said Yang. This was also because “the possibility that the US launches a new round of strategic operations to infringe on core national interests of China and Russia cannot be ruled out. Therefore, it is more urgent than before for Beijing and Moscow to be prepared. They need to establish reliable strategic deterrence capability and prevent the breakout of war.”

For Russia, however, such a Chinese missile launch detection system would be constructed primarily for early warning purposes against non-Russian approaching missiles. In the event of a fallout with China, according to Kashin, Russia would lose “virtually nothing in terms of security, while making life difficult for the United States, strengthening its relationship with a key partner, and gaining a significant economic advantage.”

Trenin shared Kashin’s confidence that Russia’s assistance to China in this highly sensitive area would not jeopardize Russia’s strategic interests should the Sino-Russian relationship turns sour. He also saw some positive impact on China’s relations with the US and other Western powers. “A China equipped with a reliable early warning system should feel more confident in relation to the other nuclear powers. These other powers, in turn, would feel more confident that the Chinese system is reliable. In principle, this mutual confidence should be a steadying force for global strategic stability,” reasoned Trenin. It is unclear if Putin shared this logic. For him, the disclosure of the project would make sure that China is on the side of Russia in the post-INF world.

Russia and China: Transcending Alliance?

In the same speech at Sochi to the Valdai audience in early October, Putin dropped a second “shoe” by claiming that the Russia-China ties were “an allied relationship in the full sense [emphasis added] of a multifaceted strategic partnership,” and “we enjoy an unprecedentedly high level of trust and cooperation.” Until this point, Putin had said several times that Russia and China had no plans for a military union. His choice of phrase in Sochi seemed to have stretched the outer limits of the current “partners-but-not-allies” (结伴不结盟) status with Beijing.

For years, particularly after the 2014 Ukraine crisis, Russia had been exploring a closer relationship, if not an alliance, with China. For its part, China had been hesitant, given its much larger stake in the stability of the existing international order. Instead, the two sides settled on phrases such as “the comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination for a new era between China and Russia,” officially unveiled in the June Moscow summit of 2019.

Presidents Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin sign statements on elevating bilateral ties to the comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination for a new era and on strengthening contemporary global strategic stability, and witness the signing of a number of cooperation documents, after their talks in Moscow, Russia on June 5. Photo: Xinhua

The alliance issue, however, continued to stretch the imagination of many, friends and foes. In his annual yearend news conference on Dec. 19, Putin walked back a bit by clarifying that Russia did not have a military alliance with China and “we do not plan to create one.” To fine-tune Russia’s China policy Sergei Lavrov, the foreign minister, publicly said three days later that Russia and China were allies only in the areas of political relations and diplomatic coordination. “We are allies when it comes to politics, the protection of international law and polycentric international relations,” he told Channel One Russia on Dec. 22.

Lavrov’s clarification was part of his extensive discussion of his recent meeting with President US Donald Trump in the White House on Dec. 10 and his meeting with Henry Kissinger in September. In both meetings, US-Russia-China triangular relations was discussed, with the assumption of taking Russia away from China. He recalled Kissinger’s preference that “it would be ideal for the United States if its relations with Russia and China are better than relations between Russia and China.” That, however, was “unrealistic,” recalled Lavrov, who said, “We will not undermine our relations with China to please the Americans,” given US sanctions and ultimatums. In contrast, “China behaved completely differently on the international stage. It is not trying to humiliate anyone with ultimatums.” As reassurance, Lavrov told his Chinese counterpart four days before his meeting with Trump that “nobody, no forces would be able to weaken the strategic trust between Russia and China (任何人、任何势力都无法挑拨俄中之间的战略互信)。

Chinese analysts were busy searching for innovative concepts around and beyond the conventional notion of alliance. Chinese Defense Ministry continued to stress the “three nos” formula (non-allied, non-confrontational, and not targeting a third party, 不结盟、不对抗、不针对第三国) as the basis for the “new type” of international relations based on principles of mutual respect, equality and justice, cooperation and win-win.

The nature, scope, and degree of a China-Russia alliance, however, remained a heated topic in China’s foreign and security policy community. Gen. Wang Haiyun (王海运), former military attaché to Russia, advocated for a quasi-allied (准同盟) relationship with Russia in the context of China-Russia-US triangular realpolitik. It was unrealistic for Beijing and Moscow to form a military alliance, which may lead to a dangerously asymmetrical bipolar structure. In facing a common strategic rival (the US), China and Russia cannot afford to go it alone (单打独斗), but ought to support each other with more effective and realistic strategic coordination to constrain (抑制) US hegemony. Wang argued that this quasi-alliance matches Xi’s “community of common destiny” (命运共同体) for common responsibility and interests, as well as Putin’s “special partnership relationship.”

Within this strategic triangle, Wang argued that China’s relationship with its strategic partner (Russia) should not be outweighed by that of its strategic rival (the US), though China-US ties remain paramount (重中之重). Instead, the “Russian factor” (俄罗斯因素) should be tapped. Although it is no longer a superpower, Russia plays an important role in balancing US power within the strategic triangle with its skillful diplomacy and intimidating military power. For the US, Wang advocates that China should have strategic confidence (战略自信) and tactical caution (战术谨慎) to prevent isolated conflicts from becoming full-scale ones.

The preference for a quasi-alliance formula was shared by many inside China’s foreign policy community, including Prof. Qiao Liang (乔良) of China’s National Defense University. For him, alliance with binding responsibility may lead to a situation in which one has to support the blunders of an ally. An informal type of relationship—particularly the “back-to-back” (背靠背), not “hand-in-hand” (手拉手) type—with Russia may be more convenient.

For some, the issue of alliance is not necessarily “to be or not to-be.” Shang Wei (尚伟) of China’s Academy of Social Sciences, for example, argued for “transcending” (超越) the practice of conventional military alliance for a simple reason: alliances are enemy oriented, particularly in wartime and during the Cold War. Shang believed that the “three nos” posture of the current Sino-Russian strategic partnership transcended the conventional military alliance. For him, alliance structure does not fit peace time.

Interestingly, Shang’s “transcending” conceptualization of the bilateral ties was echoed by Andrey Denisov (Андре́й Дени́сов), Russia’s ambassador to Beijing. His response to the alliance speculation was that “in some areas, we have transcended an alliance relationship, while not being constrained by responsibilities derived from alliance.” It appeared that as long as there were no official confirmation, there is a great deal of flexibility at the functional and operational level of the bilateral interaction.

By the end of 2019, Moscow and Beijing continued to stay with non-alliance status, at least paying lip service to such a principle. At the operational level, however, the two sides seemed to be taking specific steps toward an eventuality in which security and political situations drastically deteriorate at both regional and global levels. Should this occur, Russia and China would have the choice of taking joint actions.

In the last few months of 2019, signs of such a scenario appeared on the horizon. On Aug. 2, the Trump administration officially terminated the 1987 INF Treaty with Russia, which was seen as the beginning of the end of the arms control mechanism that regulated nuclear weapons since the Cold War. Both Russia and China were alarmed by US unilateral withdrawal. Ji Zhiye (季志业), senior advisor of the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations, described the mechanism for global nuclear and strategic stability as “on the verge of collapsing” as a result of the US exit. Indeed, the post-INF world is seen as far more unpredictable and more dangerous than the Cold War in which rules of the games were sought and created by both sides.

The direst forecast came from Russian scholar Sergei Karaganov (Сергей Караганов), Honorary Chairman of the Russian Council on Foreign and Defense Policy in Moscow. “The threat of war is now extremely high (Угроза войны сейчас чрезвычайно высока),” said Karaganov when interviewed by the influential Russian journal Sight (Взгля) on Dec. 3. For him, the coming disaster was shaped by at least three factors: military technology including automated platforms (drones with both nuclear and conventional capabilities) and cyber warfare; a lost generation as a result of the long peace; and the decay of political elites (and the rise of the “iPhone generation”) around the world. The combined effects of these trends would make coming conflicts more explosive (гораздо более взрывоопасную) than that of the Cold War.

Iran: The Beginning of the End?

The last month of 2019 was unfolding along Karaganov’s script as the fragile post-INF world system was being shaken by heightened tension between Iran and the Trump administration. On the same day Karaganov gave his Sight interview Li Shaoxian (李绍先), one of the most prominent experts of the Middle East, warned of coming danger for Iran in 2020. In his interview with Channel One on Dec. 22, Lavrov, too, warned that “Iran cannot be treated the way Washington is trying to do it. Not only do Americans grossly violate the UN Charter by refusing to comply with the UN Security Council’s binding resolution but they also rather rudely address the demands to the Islamic Republic of Iran, a country with a one-thousand-year-old civilization, traditions, and an immense sense of dignity.”

The Iran-Russia-China naval drill in the last days of 2019 was widely seen as a needed balancing act to offset the US and some of its allies in the region. The balancing effect, however, was soon outpaced by a situation on the ground. On Jan. 2, 2020, three days after the Iran-China-Russia naval drills, Iranian Gen. Qasem Soleimani was killed by US drones in Bagdad’s international airport. The killing triggered worldwide protests against the US action, and both Iran and the US threatened to retaliate and escalate.

Even without the Iran-US conflict, the 2020 US presidential election will be challenging for Moscow and Beijing. In Washington, both the Russia and China factors will be significant features of the highly charged and increasingly divisive political climate. It remains to be seen to what extent realism in US foreign policy making will be able to retain influence in the midst of the highly politicized election politics, not to mention the impeachment against the president who is seeking reelection.

The year 2019 supposed to be one of multiple anniversaries and celebrations for China and Russia: 30th anniversary for normalization of relations (1989-2019); the 70th anniversary of Sino-Soviet/Russia diplomatic ties; the 100th anniversary of Vladimir Lenin’s declaration to abolish all of the Czarist unequal treaties with China, thus winning the hearts and minds of the Chinese; and the 400th anniversary of the first official contact (first Russian mission to Beijing in 1619). At the onset of the new decade, however, the mounting tensions, uncertainties, and hostilities at both global and regional levels—which made 2019 the most challenging year for Moscow and Beijing in recent times—may turn out to have been relatively minor irritants compared to those of coming years.

Sept. 5, 2019: Russian President Vladimir Putin meets Chinese Vice Premier Hu Chunhua (胡春华) at the 5th Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok.

Sept. 16-21, 2019: The Russian military conducted the Center-2019 (Центр-2019) military exercise with 130,000 soldiers, 20,000 pieces of equipment, 600 aircraft, and 15 warships. The PLA sent 1,600 troops, 300 pieces of equipment and 30 aircraft, and 750 personnel attended from Pakistan, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

Sept. 17, 2019: The Shanghai Cooperation Organization holds a meeting of its Council of National Coordinators in Beijing. They discuss foreign policy coordination for countering greater security, political and economic risks. They also work on the upcoming annual Prime Ministerial Meeting in Tashkent.

Sept. 19, 2019: SCO holds its 2nd meeting of railway administration heads in Nur-Sultan, capital of Kazakhstan. The SCO decided to start this new mechanism at its Qingdao summit in June 2018 and held its first meeting Sept. 9, 2018 in Tashkent.

Sept. 24, 2019: SCO holds its 7th meeting of heads of territorial authorities for border area emergencies of SCO member states in Chelyabinsk in the South Urals.

Sept. 25, 2019: Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi and Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov join a six-nation foreign ministerial meeting on the Iran nuclear issue at UN headquarters in NYC. Participants also include foreign ministers of Iran, France, Germany, and UK.

Sept. 26, 2019: The SCO holds its 18th meeting of ministers of foreign trade in Tashkent.

Sept. 27, 2019: Wang and Lavrov meet on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly session.

Sept. 27, 2019: SCO holds its first meeting of ministers of environmental protection in Moscow.

Oct. 1, 2019: The 17th Meeting of the Prosecutors General of the SCO Member States is held in Bishkek. They focus on cooperation against illegal drug trafficking.

Oct. 2, 2019: Chinese and Russian presidents, prime ministers and foreign ministers exchange congratulatory telegraph messages for the 70th anniversary of Sino-Russian diplomatic relations.

Oct. 3, 2019: In his speech to the 16th Valdai Forum in Sochi of Russia, Putin reveals that Russia is helping China with a missile attack early-warning system.

Oct. 9, 2019: Reception in Beijing for the 70th anniversary of Sino-Russian/Soviet diplomatic relations. Li Zhanshu, member of the standing committee of the CCP Politburo and Chairman of the Standing Committee of the Chinese People’s Congress, and Russian Ambassador to Beijing Andrey Denisov (Андре́й Дени́сов) join.

Oct. 9, 2019: Director-General of the Information Department of the Foreign Ministry Hua Chunying (华春莹) meets in Beijing at request of visiting Maria Zakharova (Мария Захарова), spokesperson for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and director of the Information and Press Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Russia. They exchange views on the international situation, and press and media cooperation between the two Foreign Ministries.

Oct. 11-18, 2019: Russia and China stage “Cooperation-2019” antiterror drills in Russia’s Novosibirsk Region, the 5th joint exercise between law-enforcement units of the two countries since 2007.

Oct. 20-22, 2019: Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu joins 9th Beijing Xiangshan Forum (香山论坛), a defense issue conference hosted by the China Association of Military Science (CAMS). Shoigu was the first Russian defense minister to join the forum, together with 600 participants from 76 countries, including 23 defense ministers and 6 chiefs of general staff.

Oct. 31-Nov. 1, 2019: Expert Working Group (EWG) affiliated with the Meeting of Defense Ministers of the SCO holds its 7th meeting in Moscow. The Russian side suggested that SCO defense chiefs be invited to a joint meeting with counterparts of the CIS and the CSTO in June 2020 in Moscow. They also discuss the SCO’s “Peace Mission-2020” to be held in Russia.

Nov. 6-7, 2019: Tashkent hosts the 7th scientific and practical conference of the SCO’s Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure (RATS). Representatives of the UN, CIS, CSTO, OSCE, and CICA join.

Nov. 8, 2019: New Delhi hosts the 10th SCO Meeting of Heads of Emergency Prevention and Relief Agencies, chaired by India’s Minister of Home Affairs Amit Shah. India also hosted a SCO Joint Exercise on Urban Earthquake Search and Rescue on Sept. 4 at Ambedkar International Centre in Janpath, New Delhi.

Nov. 12, 2019: SCO Expert Group on International Information Security holds a regular meeting in Moscow. They draft a joint statement for cooperation in international information security to be issued at the 2020 SCO summit in Russia.

Nov. 13-14, 2019: BRICS holds its 11th summit in Brasilia,. Chinese and Russian presidents meet on the sidelines of the summit on Nov. 13.

Nov. 21, 2019: Moscow hosts SCO’s 5th Meeting of Heads of Science and Technology Ministries. First Deputy Minister of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation Grigory Trubnikov is chair.

Nov. 23, 2019: Wang meets Lavrov in Osaka on the sidelines of the G20 foreign ministerial meeting.

Nov. 25, 2019: China, Russia, and South Africa conduct joint naval exercises in Cape Town,. Three Russian ships, two South African ships, and one Chinese ship join the drills.

Nov. 25, 2019: Chinese and Russian parliamentarians hold dialogue in Beijing on how to offset foreign interference in domestic affairs.

Nov. 25, 2019: Chinese President Xi Jinping meets a delegation of Russia’s United Russia party led by Chairman of the United Russia’s Supreme Council Boris Gryzlov in Beijing. The Russian group visited Beijing for the 7th meeting of the dialogue mechanism between the ruling parties of China and Russia.

Nov. 27, 2019: Chinese Deputy Foreign Minister Mao Zhaoxu (马朝旭) and Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov (Сергей Рябков) and Russia hold their first consultation on intermediate-range ballistic missiles in Beijing.

Dec. 2, 2019: Xi and Putin conduct video conference while presiding over the opening of the eastern section of the Power of Siberia gas line. The 3,000-km gas line, contracted in 2014, will eventually provide China with 38 billion cbm per year, or 30% of China’s annual gas import.

Dec. 4, 2019: 15th Sino-Russian consultation on strategic and security issues is held in Shanghai, co-chaired by Yang Jiechi (杨洁篪), director of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the Communist Party, and Nikolai Patrushev (Никола́й Па́трушев), secretary of the Security Council of the Russian Federation. Chinese President Xi Jinping met Patrushev Dec. 2 in Beijing.

Dec. 5, 2019: 12th Sino-Russian Commission of Friendship, Peace and Development is held in Beijing. Vice President Wang Qishan met with members of the commission.

Dec. 9, 2019: Beijing hosts a meeting of divisional heads of SCO member state defense ministries for international military cooperation, and the 8th meeting of the Expert Working Group for the SCO Defense Ministers (SCO EWG).

Dec. 16, 2019: China and Russia jointly propose to the UN Security Council a political resolution for the Korean issue, including lifting a ban on North Korean exporting statues, seafood and textiles; promoting bilateral (US-North Korea) and multilateral (such as six-party) dialogues, etc.

Dec. 19, 2019: Wang takes part in telephone talks with Lavrov. The two exchange views on the Korean Peninsula nuclear issue, international situation of common concern and other topics.

Dec. 22, 2019: Lavrov tells Russian media that Russia is not going to worsen relations with Beijing to make the United States happy.

Dec. 27-30, 2019: China, Russia, and Iran conduct a four-day naval exercise in the northern part of the Indian Ocean and Gulf of Oman, the first trilateral exercise between the three armed forces since the 1979 Islamic Revolution. China dispatched the Xining, a guided missile destroyer, to the drills.

Dec. 31, 2019: Russian and Chinese presidents and prime ministers exchange New Year greetings.