Articles

The outbreak of COVID-19, first in China and then in South Korea, placed plans for a highly anticipated summit between Xi Jinping and Moon Jae-in on hold. Beijing and Seoul’s priorities focused on fighting the virus together through aid exchanges, a new inter-agency mechanism led by their foreign ministries, and multilateral cooperation with Japan and ASEAN. As cases spread across borders, political frictions emerged over entry bans and relief supplies. The public health crisis triggered efforts to mitigate its socioeconomic repercussions, raising questions over long-term US influence. The virus also dramatically interrupted the normal diplomatic and economic interactions between China and North Korea.

The outbreak of the novel coronavirus COVID-19 virus, first in China and then in South Korea, placed plans for a highly anticipated Xi-Moon summit on hold. Beijing and Seoul’s priorities focused on fighting the virus together through aid exchanges, a new inter-agency mechanism led by their foreign ministries, and multilateral cooperation with Japan and ASEAN partners. As cases spread across borders, political frictions emerged over entry bans and relief supplies. The public health crisis triggered regional efforts to mitigate its socioeconomic repercussions, raising questions over the United States’ long-term influence. COVID-19 dramatically interrupted the normal flows of diplomatic and economic interaction between China and North Korea.

Containment of the virus quickly consumed the Chinese leadership’s attention by mid-January and became a focal point in North Korean state media by the end of January. The virus was the pretext for an exchange of messages between Kim Jong Un and Xi Jinping on February 2, but dramatically curtailed official diplomatic, tourist, and economic exchanges during the first part of 2020. It is not yet clear whether the virus also affected the growing volume in 2019 of ship-to-ship transfers of oil and coal between North Korea and China under the tacit protection of Chinese state authorities.

Xi-Moon Summit Talks on Hold

South Korean President Moon Jae-in declared “war” on COVID-19 on March 3, six weeks after the country’s first confirmed case on January 20, and two months after the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) began reporting suspected cases in China. South Korea recorded the highest number of confirmed cases outside China as infection peaked in late February. By the time the World Health Organization (WHO) called COVID-19 a global pandemic on March 11, it also identified China and South Korea as countries with “significantly declining” cases.

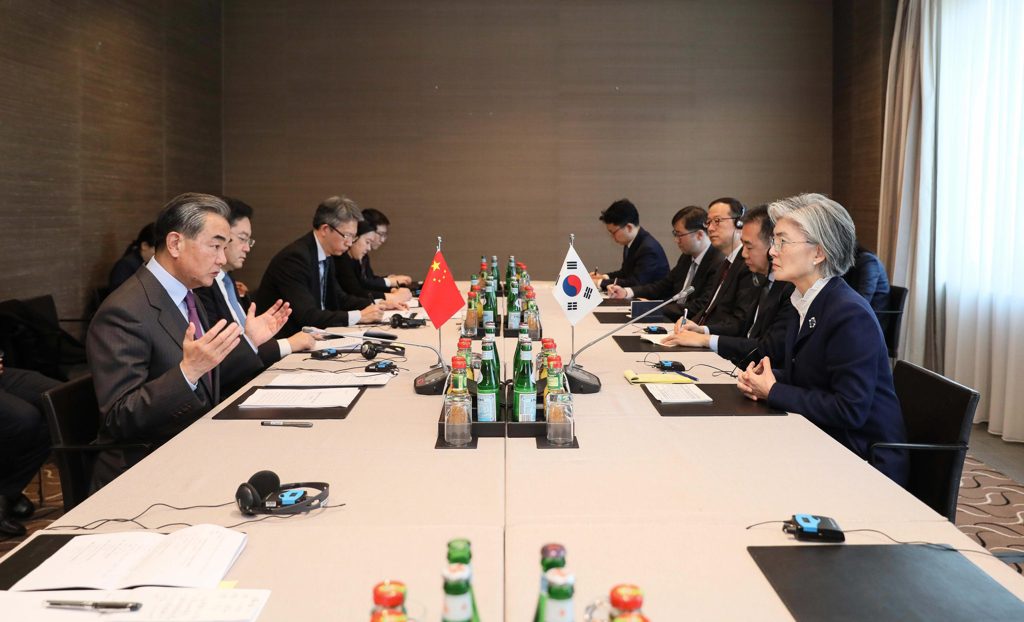

Foreign ministers Wang Yi and Kang Kyung-wha met on the sidelines of the Munich Security Conference on February 15, where they continued to support Xi-Moon summit plans. After months of speculation, Kang finally indicated at an April 28 parliamentary meeting that Xi’s visit to South Korea would indeed be unlikely due to the coronavirus pandemic. The visit was planned for the first half of 2020 after the summit in Beijing last December. In his New Year address on January 7, Moon vowed to upgrade bilateral relations in anticipation of separate visits by Xi and Premier Li Keqiang, expressed hopes for advancing trilateral cooperation with Japan, and outlined plans for boosting South Korea’s export competitiveness in light of US-China trade tensions. During his New Year press conference on January 14, he promised to coordinate his regional economic policies with China’s Belt and Road Initiative, and emphasized Beijing’s role in resolving the North Korea nuclear issue. China’s foreign ministry in response expressed Beijing’s readiness to advance regional dialogue and inter-Korean engagement.

Figure 1 Foreign Ministers Wang Yi and Kang Kyung-wha participate in bilateral talks in Munich. Photo: Yonhap

Those priorities quickly shifted by January 28, when Moon promised “support and cooperation” in China’s fight against COVID-19 in a letter to Xi. In telephone talks with Wang the same day, Kang indicated South Korea’s willingness to provide medical supplies, and coordinated plans for evacuating about 700 Koreans from Wuhan, Hubei province, where the virus originated. Evacuations were completed in three rounds on January 31, February 1, and February 12, combined with South Korea’s deliveries of emergency supplies to China as part of a total $5 million in aid announced on January 30.

Effects of Quarantine on China-North Korea Diplomacy

Concerns about the spread of the virus quickly led North Korea to impose a comprehensive quarantine on air and ground transit routes between China and North Korea at the end of January. Travel companies were banned from bringing tourists to North Korea on January 22, a one-month quarantine on overseas arrivals was announced the following week, and most air, port, and train routes were suspended during the last week of January. Foreign diplomats located in Pyongyang were restricted to their compounds throughout February. Many diplomatic representatives withdrew and closed their embassies once an evacuation flight to Vladivostok was arranged on March 9, though Chinese embassy personnel were reported to have remained in country during and following the quarantine period.

North Korea announced the appointment of former defense commander Ri Son Gwon as its new minister of foreign affairs, replacing veteran diplomat Ri Yong Ho, who had met with Xi Jinping on December 22 in Beijing as one of his last official international diplomatic engagements. But due to the coronavirus outbreak, Ri did not have any substantive external engagements through the end of April. Kim Jong Un’s letter to Xi Jinping reported on February 2 offering his support to Xi’s coronavirus response efforts was the single public leadership interaction between Pyongyang and Beijing during the first four months of 2020. China announced that it sent COVID-19 test kits to North Korea for future use on April 27, months following North Korea’s quiet appeals to international aid organizations since early February for COVID-19 related supplies. China had previously exported over $50 million in medical supplies to North Korea in 2019.

In a Reuters interview ahead of the Munich Security Conference in February, Wang Yi reiterated China’s position on Korean Peninsula peace and denuclearization, stating that the “dual-track approach” supported by Moscow and Seoul awaits “a real consensus within the US.” Working-level defense talks between Beijing and Seoul on January 16 focused on advancing denuclearization and peace after the breakdown of US-DPRK talks after the February 2019 Trump-Kim summit.

Coronavirus Cooperation: Interagency Mechanisms and Aid Exchanges

Figure 2 Chinese and ROK officials participate in a video conference as part of their established joint response. Photo: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China

The public health crisis surrounding the coronavirus prompted close cooperation between China and South Korea from the onset, most notably in the form of interagency institutional mechanisms and bilateral aid exchanges. Xi and Moon discussed information-sharing and other ways to cooperate in telephone talks on February 20, when South Korea reported its first coronavirus-related death. The foreign ministries led the first working-level video conference on joint contingency measures on March 13, launching a new cooperation mechanism on COVID-19 including health, education, customs, immigration, and civil aviation agencies.

China’s foreign ministry called it not just a step toward implementing Xi and Moon’s “important consensus,” but also a “reference for other countries to join hands to fight the epidemic.” Moon’s approach stood in contrast to the Trump administration’s early ban on travel from China as well as recommendations to ban flights to China from the Korean Medical Association. In an extensive China Daily report in March on China-ROK cooperation, Wang Junsheng at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) agreed that “the two neighbors will serve as a model for other countries,” many of which have “overreacted” to Chinese and South Korean cases. For Yu Wangying at Sungkyunkwan University, the “mutual assistance” from governments and society demonstrated “people-to-people connectivity” and “deepened mutual understanding.”

A day before pledging $5 million in government aid, South Korea’s foreign ministry revealed on January 29 that two Korean civic groups would send medical supplies to China. Local governments, companies, and the private sector contributed relief aid to Wuhan and other regions from late January. New Consul General Kang Seung-seok arrived in Wuhan on February 20 with additional relief supplies from various sectors. As a Global Times interview with Kang indicated, his arrival “won praises” from China’s foreign ministry and “touched the hearts of many Chinese citizens.” In his China Daily op-ed on February 27, new PRC Ambassador to Seoul Xing Haiming reflected on local gestures of emotional support in South Korea, and shared experiences fighting outbreaks like SARS in 2002-2003 and MERS in 2015.

Among the first to donate supplies to China, South Korea soon became a recipient of China’s reciprocal global aid at intergovernmental, technical, and subnational levels. China’s foreign ministry on February 20 identified the South Korean case as a primary example of such aid exchange, praising the ROK Embassy slogan of Moon’s early words to Beijing, “China’s problems are our problems.” Shanghai was the first Chinese municipal government to support South Korea by providing masks to the hardest-hit regions of Daegu and North Gyeongsang province on February 27. Dismissing foreign media claims on China’s export restrictions on surgical masks, the foreign ministry on March 9 pointed to China’s 1.1 million mask donations to South Korea and additional donations from Chinese businesses and eight sister-city regions. As the Chinese state media later declared, “made-in-China supplies reinforce world’s war on COVID-19.”

Coronavirus Conflict: Entry Bans and Domestic Backlash

In South Korea, Seoul’s $5 million aid plan to China still drew domestic backlash for threatening domestic supplies. When the plan was announced on January 30, South Korea also reported its first suspected human-to-human transmission. During a crackdown between February 6 and 12, the Korea Customs Service detected illegal shipments of 730,000 masks worth $1.18 million, mostly by Chinese nationals. A foreign ministry official told the media on February 28 that South Korea would only provide half of its promised aid to China through international agencies.

Frictions in China and South Korea’s fight against the coronavirus emerged most importantly over entry restrictions. Pointing to Seoul’s concerns about the economic impact and Xi’s planned visit, a Korea Herald editorial on March 2 argued that Moon “should have been more active in banning entry from China without being bound by considerations other than public health.” Jeju residents voiced the earliest concerns in January by pressing their regional government to ban Chinese travelers under its visa-free program. By the time Seoul announced a temporary entry ban from February 4 on foreigners who have been in Hubei, more than 650,000 citizens supported an online petition demanding a ban on travelers from China entirely. According to one survey in February, 64% of respondents supported a ban on visitors from China, while 33% found it unnecessary.

Xing Haiming’s first press conference remarks as PRC ambassador on February 4 raised controversy for suggesting Seoul’s failure to follow WHO recommendations against travel restrictions. Unannounced quarantine measures by Chinese provincial authorities from February 25 especially angered South Koreans, who criticized the Moon administration for not taking “reciprocal measures.” Kang expressed South Korea’s concerns to Wang during telephone talks on February 26, which Deputy Foreign Minister Kim Gunn also voiced to Xing in Seoul. As global attention on China’s entry restrictions heightened, the PRC foreign ministry on February 28 released a statement on health regulations indicating that Chinese and foreign nationals are “treated as equals.” But in nationalist media outlet Global Times, experts like Da Zhigang at the Heilongjiang Academy of Social Sciences warned against re-imported cases from South Korea, especially via missionary activities of religious groups like Shincheonji Church, linked to more than half of the country’s cases.

Seoul filed an official written complaint on March 16 protesting Beijing municipality’s decision to quarantine incoming travelers in designated facilities at their own expense. The complaint came just two days after Xi sent a message of sympathy to Moon reciprocating South Korea’s show of support. By mid-March, 22 Chinese regions were implementing tightened quarantine measures for travelers from South Korea. South Korea’s foreign ministry again called in Xing for a meeting with Deputy Foreign Minister Kim Gunn on March 27 after Beijing announced a temporary suspension of the entry of foreigners. The second meeting of the China-ROK mechanism on COVID-19 reached agreement on April 29 to initiate a fast-track system simplifying entry procedures for business travelers effective May 1. Although the system applied to all of South Korea, only half the 10 designated Chinese regions could bring it into force given the status of flight operations. China’s foreign ministry called it a “groundbreaking initiative” between the two neighbors and economic partners as “epidemic prevention and control becomes a new normal.”

The Steep Downturn in China-North Korea Trade and Its Implications

A major casualty of North Korea’s self-imposed quarantine was China-North Korea official trade, which hit levels of exchange even lower than those recorded at the height of sanctions in early 2018. Overall trade dropped by 24% compared to the previous year according to Chinese customs data for January and February. China’s exports fell to $198 million for the first two months of the year, while imports from North Korea dropped 74% to only $10 million, reflecting the severity of the impact of the quarantine.

North Korea has reportedly placed a ban on imports of consumer goods as part of the quarantine, but Seoul National University Professor Kim Byeong-yeon speculates that the real reason behind import restrictions is foreign currency shortages inside North Korea. He cites reports of “panic buying” and the resumption of public bond issuance for the first time in 17 years as evidence that supports this conclusion. If North Korea does face a domestic currency crunch, China would face even greater pressure to provide support to stave off a humanitarian and political crisis should economic conditions drastically worsen inside North Korea.

China Abets North Korean Sanctions Evasion

The anticipated March 2020 release of the 2020 UN Panel of Experts report on North Korea was delayed to April due to objections from China. The report came against the backdrop of a draft UNSC resolution co-sponsored by China and Russia last December advocating the loosening of sanctions on North Korea. A draft of the Panel of Experts report, leaked to the media in February, drew attention to extensive ship-to-ship transfers of oil, coal, and sand that regularly occurred in Chinese territorial waters during 2019. North Korea is reported to have utilized foreign-flagged tankers to make 64 deliveries of refined petroleum products ranging between 560,000 and 1.531 million barrels, in excess of the 500,000 limit imposed by UNSC resolutions on North Korean petroleum imports. In addition, North Korea is suspected of having illicitly exported 2.8 million metric tons of coal to China worth an estimated $370 million via ship-to-ship transfers, and of having earned over $120 million by selling fishing rights in North Korean waters to Chinese vessels.

The regularity and location of the suspected transfers near Zhoushan, home of the China’s East Sea Fleet, suggest that Chinese state authorities have tacitly enabled North Korean ships and Chinese-controlled counterparts to evade UN sanctions on North Korea through nonenforcement of the resolutions. US National Security Advisor Robert O’Brien stated in response that “The Chinese have to enforce the sanctions against North Korea. They’ve got to stop the ship-to-ship transfers. They have to send the labor—the folks who are engaged in labor in China, and then sending remittances back to North Korea to keep the economy going. We need the Chinese to assist us as we pressure the North Koreans to come to the table.”

Constraints imposed by China on the content of the UN Panel of Experts reports have meant that specific information detailing Chinese nonenforcement of sanctions has come from independent research organizations such as the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) and the Japanese foreign ministry. The RUSI report entitled “The Phantom Fleet: North Korea’s Smugglers in Chinese Waters” provides extensive photographic and other evidence showing the routes, locations, and cargos of vessels involved in UN sanctions evasion through ship-to-ship transfers. China has routinely been identified as an overseas base for North Korean hacking and cybertheft operations, but the PRC embassy in Pyongyang has also been reported as the victim of North Korean hacking operations, according to a Beijing-based security firm Qihoo 360.

COVID-19’s Economic Impact on China and South Korea

COVID-19’s economic impact on China and South Korea heightened concerns over the global repercussions. During video talks on April 17, Commerce Minister Zhong Shan and Industry Minister Sung Yun-mo agreed to mitigate disruption to global supply chains, especially given South Korea’s heavy dependence on China for labor-intensive products in sectors like automobiles. China’s economy declined by 6.8% in January-March 2020 after the coronavirus shutdown, challenging Beijing’s goal of doubling the economy from 2010 levels by 2020. The IMF projected in April that China’s economy is expected to grow by 1.2% in 2020, 4.9% lower than in 2019, while South Korea’s economy will shrink by an estimated 1.2%. Asia-Pacific growth overall is projected to be worse than during the global or Asian financial crises, with the United States and EU, key trading partners, to be hit even harder. The Asian Development Bank estimated in March that South Korea’s GDP could shrink by up to $16.5 billion in 2020 in the worst-case scenario of prolonged outbreaks and declining Chinese consumption. According to South Korea’s trade ministry, total exports declined by 24.3% in April on-year, the biggest decline since 2009. Exports to China declined by 6.2% in March on-year, but FDI pledged from China grew almost threefold in January-March 2020 to $1.46 billion, driven by service-sector investment.

According to the China Institute for Reform and Development, trilateral economic cooperation with Japan is critical in light of newly-emerging trends of regionalization and localization. Director-General of the Ministry of Commerce’s Department of Foreign Trade Li Xingqian identifies cooperation with South Korea and Japan among China’s priorities for stabilizing foreign trade, through targeted support to enterprises and initiatives like the trilateral FTA and Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). Wang Jinbin at Renmin University similarly calls for signing the trilateral FTA and RCEP this year as part of a post-pandemic trade development strategy in Asia, citing the growing importance of regionalization, an ailing global industrial chain, and “reverse globalization.” According to Wang Junsheng at CASS, the coronavirus outbreak combined with US protectionism “has given them a push to cooperate” despite tensions among the three countries last year. As Tian Yun at the Beijing Economic Operation Association argues, China’s diversifying export market may place it in a better position to deal with the trade war with Washington. ASEAN emerged as China’s biggest trade partner in the first quarter of 2020, surpassing the EU and the United States. A Boston Consulting Group report in March indicated that US-China trade frictions have especially damaged US leadership in the semiconductor industry, predicting that South Korea will take over in a few years and China will lead in the long term.

Asian Models and Implications for the United States

The regional spread of the coronavirus reinforced Beijing and Seoul’s cooperation with Japan and other partners since RCEP talks in Bali on February 3-4. Foreign Ministers Wang Yi, Kang Kyung-wha, and Toshimitsu Motegi held a trilateral video conference on coronavirus cooperation on March 20, three days after director-general level talks. According to CASS scholars, the meeting highlighted the need to maintain cross-border economic exchanges, high-level political consensus, favorable public opinion, and multilateral coordination. In an interview with People’s Daily earlier that month, Deputy Secretary-General of the Trilateral Cooperation Secretariat Cao Jing claimed that such efforts would “inject new impetus to deepening their cooperation,” identifying public health, scientific innovation, and the trilateral FTA as priorities. Premier Li, President Moon, and Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzo joined a special ASEAN+3 video summit on April 14 affirming their commitment to a collective regional response. The joint statement on COVID-19 identified various proposals including the creation of a regional reserve of medical supplies and an emergency response fund.

Figure 3 Premier Li speaks in Beijing with ASEAN Plus Three leaders via video conference in April. Photo: China Daily

Such initiatives inspired Chinese debate on Asian regional cooperation and lessons for the West. China Daily commentators suggested that East Asian countries are developing innovative models to “fill in the gaps” in the supply of global public goods from organizations like the WHO. The China-ROK mechanism and trilateral foreign ministers meeting on COVID-19 exemplified comprehensive approaches to mitigate the socioeconomic effects, showing that international public health governance goes beyond health sector cooperation. Wang Sheng at Jilin University saw the public health crisis as an important driver of trilateral cooperation with Japan on non-traditional security, pointing to China and South Korea’s similar responses at home. In a Global Times op-ed, Wang Junsheng attributed their success compared to Western counterparts to their governments’ early measures, advanced quality of health sectors, and their people’s stronger willingness to “obey and follow” government recommendations. He further criticized the West’s “hypocritical” tendency to reject China’s model while seeking to learn from democratic South Korea, arguing that “the three countries are coordinating efforts to deal with discrimination against Asians.” A CGTN opinion piece on April 15 concluded that “US influence in East Asia continues to wane” since COVID-19, highlighting tensions with South Korea over defense burden-sharing.

Conclusion: Post-Pandemic China-Korea Relations

At the start of 2020, Moon called Xi’s planned visit “an opportunity for South Korea-China relations to make an epoch-making leap.” Despite the visit’s delay, joint efforts to fight the coronavirus pandemic consolidated claims of deepened friendship. Briefing the Chinese media in April, South Korea’s Consul General in Wuhan Kang Seung-seok identified intergovernmental information sharing, nongovernmental donations, and emotional support as the “biggest gain” for both countries, expressing hopes that such friendship will “serve as a basis for further bilateral exchanges in the future.” After telephone talks with Moon in February, Xi reassured that “friendly feelings between the Chinese and South Korean people will grow even deeper.” As China’s foreign ministry spokesperson echoed, “after being tested by this pandemic, the friendship and mutual trust between the two peoples in China and the ROK will be strengthened.” As China Daily summed up, the China-South Korea case shows that “East Asia is enhancing its institutions, interagency coordination, people-to-people ties and information sharing.”

Such favorable assessments lay aside looming domestic and global uncertainties surrounding post-pandemic relations. One poll conducted by a US marketing agency in March 30-April 3 showed that Chinese consumers had the most positive view of their government’s response to the outbreak (79%), followed by Britain (50%), South Korea (43%), and the United States (34%). Even as opposition voices on diplomacy with China and economic challenges grew louder, a Gallup Korea poll showed that Moon’s approval rating increased from 44 to 57% in March-April, the highest since October 2018. The ruling Democratic Party’s win in the parliamentary elections on April 15 was seen to boost his foreign policy agenda at a time of growing concern over North Korea’s belligerence, tensions with Japan, and the future of the US-ROK alliance. According to Ma Weying’s assessment of Moon’s future diplomacy, although the US-ROK alliance will remain the “cornerstone,” South Korea’s military and political dependence on Washington is likely to be limited since “Moon values autonomy.” Having recovered from the THAAD fallout, Seoul will continue to “seek a balance between China and the US.” While Moon will seek friendly ties with China to meet economic goals, his China policy will also depend on US relations and Korean Peninsula conditions. Although Seoul relied heavily on Xi’s planned visit this year to advance Moon’s regional agenda, bilateral priorities remain on battling the virus and its economic repercussions.

Research assistance and chronology compilation provided by Chenglong Lin, San Francisco State University.

Jan. 1, 2020: Kim Jong Un receives a New Year’s letter from the General Association of Koreans in China.

Jan. 2, 2020: After Kim declares plans to develop “new strategic weapons,” China urges the United States and North Korea to remain committed to peacefully resolving the nuclear issue.

Jan. 3, 2020: China’s UN Ambassador Zhang Jun expresses support for a China-Russia resolution aimed at easing sanctions on North Korea.

Jan. 4, 2020: South Korea seizes Chinese fishing boats for illegally fishing in its waters in the Yellow Sea.

Jan. 7, 2020: South Korean activists protest Chinese actions against Hong Kong demonstrators.

Jan. 7, 2020: South Korean President Moon Jae-in in his New Year’s address expresses hopes for advancing China-ROK ties.

Jan. 8, 2020: The Korean Centers for Disease Control begins reporting suspected cases of pneumonia-like illness spreading in China.

Jan. 10, 2020: South Korea asks China to provide information on a new type of coronavirus.

Jan. 13, 2020: The Korea Tourism Organization announces that about 3,500 Chinese students will travel to South Korea on winter field trips until early February.

Jan. 14, 2020: Pak Kyong Il, vice-chairman of the Korean Committee for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries and chairman of the DPRK-China Friendship Association, Chinese ambassador to the DPRK Li Jinjun, and other officials attend a friendship meeting in North Korea for Lunar New Year.

Jan. 14, 2020: The United States sanctions two DPRK entities including a China-based lodging facility for involvement in labor exports violating international sanctions.

Jan. 14, 2020: Moon discusses cooperation with China in his New Year’s press conference.

Jan. 15, 2020: President Trump during a signing ceremony for a phase-one trade deal with China acknowledges China for “helping us with North Korea.”

Jan. 15, 2020: People’s Republic of China foreign ministry responds to Moon’s New Year press conference.

Jan. 16, 2020: PRC and ROK officials attend the 19th Meeting of ASEAN+3 Tourism Ministers in Brunei.

Jan. 16, 2020: China and South Korea hold working-level defense talks in Seoul.

Jan. 16, 2020: Pak Kyong Il, vice-chairman of the Korean Committee for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries and chairman of the DPRK-China Friendship Association, Chinese ambassador to the DPRK Li Jinjun, and other officials attend a friendship film show in North Korea.

Jan. 18, 2020: A DPRK delegation including North Korea’s Ambassador to China Ji Jae-ryong and Ambassador to the UN Kim Song leave Beijing for Pyongyang.

Jan. 20, 2020: KCDC reports the first confirmed coronavirus case in South Korea. China’s foreign ministry indicates that China has been working with South Korea, Japan, and Thailand to control the spread of the virus.

Jan. 22, 2020: Foreign tour agencies report that North Korea has temporarily closed its borders with China.

Jan. 22, 2020: DPRK Embassy in Beijing hosts a Lunar New Year reception, attended by PRC Vice Foreign Minister Luo Zhaohui and other officials.

Jan. 22, 2020: Korea-China Air Quality Joint Research Team releases research findings that show ultrafine dust in Beijing and Seoul contain similar elements.

Jan. 23, 2020: Korean Air Lines is South Korea’s first airline to announce a planned suspension of flights to Wuhan.

Jan. 25, 2020: KCDC designates China entirely as a “coronavirus watch” zone. ROK foreign ministry raises its travel advisory level for Wuhan and surrounding areas in Hubei province.

Jan. 28, 2020: In his reply to President Xi Jinping’s congratulatory birthday letter, Moon expresses support for Beijing’s efforts to contain the spread of coronavirus.

Jan. 28, 2020: ROK foreign ministry issues a travel alert for all of China, Hong Kong, and Macau.

Jan. 28, 2020: Foreign ministers Wang Yi and Kang Kyung-wha hold telephone talks.

Jan. 28, 2020: North Korea’s Rodong Sinmun reports strengthened measures against the coronavirus.

Jan. 29, 2020: Asan and Jincheon residents protest South Korea’s decision to bring evacuees from Wuhan. Jeju residents urge the regional government to ban Chinese travelers under its visa-free program.

Jan. 29-30, 2020: ROK foreign ministry announces medical aid to China from two Korean civic groups and separate plans to send China $5 million in aid to fight the coronavirus.

Jan. 30, 2020: South Korea reports its first suspected human-to-human transmission case of coronavirus.

Jan. 30, 2020: A South Korean plane arrives in Wuhan to evacuate South Korean nationals.

Jan. 30, 2020: South and North Korea temporarily close their Kaesong liaison office due to coronavirus concerns. North Korea plans to close all foreign transportation routes according to South Korean media.

Jan. 30, 2020: Jeju government and justice ministry discuss a temporary suspension of a visa-free program for Chinese visitors.

Jan. 30, 2020: New PRC Ambassador to South Korea Xing Haiming arrives in Seoul.

Jan. 31, 2020: ROK Vice Foreign Minister Cho Sei-young and PRC Ambassador Xing Haiming meet in Seoul.

Jan. 31, 2020: Korean evacuees from Wuhan arrive in Seoul. Asan and Jincheon residents remove protest signage. President Moon thanks them via Twitter.

Jan. 31, 2020: North Korea is reported to have closed all air and railway routes across borders with China, and suspended plans to remove South Korean-built facilities at the Mt. Kumgang resort.

Feb. 1, 2020: South Korea’s second evacuation plane arrives in Seoul with nationals from Wuhan.

Feb. 1, 2020: Kim Song-nam, first vice director of the WPK, arrives at Beijing Capital International Airport.

Feb. 1, 2020: KCNA reports that Kim Jong Un has sent a letter of sympathy to Xi, and that North Korea has sent financial aid to the CCP.

Feb. 2, 2020: South Korea announces a temporary entry ban on foreigners who have recently been in Hubei, effective Feb. 4.

Feb. 3, 2020: An Asiana Airlines cargo flight leaves for Wuhan to deliver relief aid.

Feb. 3-4, 2020: ASEAN and dialogue partners hold a high-level meeting on RCEP in Bali.

Feb. 4, 2020: Ambassador Xing Haiming holds his first press conference at the PRC Embassy.

Feb. 6, 2020: ROK Deputy Foreign Minister for Political Affairs Kim Gunn and Chinese Ambassador to South Korea Xing Haiming meet in Seoul.

Feb. 7, 2020: Moon receives the credentials of PRC Ambassador to South Korea Xing Haiming.

Feb. 10, 2020: North Korea’s Rodong Sinmun reports the WHO’s recommendation not to use “Wuhan” in naming the coronavirus.

Feb. 10, 2020: A draft UN report shows that North Korea exported about $370 million worth of coal last year in violation of UN sanctions, largely via illicit ship-to-ship transfers with China.

Feb. 10, 2020: China’s foreign ministry in an online daily briefing expresses appreciation for South Korean assistance to fight the coronavirus.

Feb. 11, 2020: China’s Permanent Mission to the UN expresses concern over leak of a UN draft report on DPRK sanctions.

Feb. 11, 2020: A Red Cross report shows that North Korea has dispatched about 500 workers to the border with China to prevent a coronavirus outbreak.

Feb. 12, 2020: South Korea’s third evacuation plane arrives in Seoul from Wuhan carrying ROK citizens and Chinese relatives.

Feb. 12, 2020: Rodong Sinmun praises Xi’s medical site visits in China’s efforts to fight the coronavirus.

Feb. 13, 2020: Korea Customs Service announces it has detected illegal shipments of 730,000 masks worth $1.18 million, mostly by Chinese nationals, in a crackdown since February 6.

Feb. 13, 2020: ROK Education Minister Yoo Eun-hae announces planned support measures for Chinese students returning to local universities.

Feb. 14, 2020: PRC State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi in a Reuters interview during the Munich Security Conference reiterates China’s position on the Korean Peninsula.

Feb. 15, 2020: Wang and Kang meet on the sidelines of the Munich Security Conference.

Feb. 16, 2020: Kim Jong Un receives a congratulatory letter from the General Association of Koreans in China on the occasion of Kim Jong Il’s birth anniversary.

Feb. 19, 2020: ROK foreign ministry sends a fourth round of relief supplies to Wuhan, and announces plans to send aid to other Chinese regions.

Feb. 19, 2020: Hubei Provincial Foreign Affairs Office Director Qin Yu welcomes new ROK Consul General in Wuhan Kang Seung-seok, who arrives with relief supplies.

Feb. 20, 2020: Xi and Moon hold telephone talks.

Feb. 20, 2020: PRC, ROK, and Japanese foreign ministers hold a trilateral videoconference on coronavirus cooperation.

Feb. 21, 2020: A UN Security Council report shows that China and Russia supplied 22,730 tons and 30,180 tons of refined oil respectively to North Korea in 2019.

Feb. 21, 2020: Hubei Party Secretary Ying Yong and ROK Consul General in Wuhan Kang Seung-seok meet.

Feb. 22, 2020: WHO indicates that, besides the Diamond Princess cruise ship in Japan, South Korea has the highest number of confirmed coronavirus cases outside China.

Feb. 25, 2020: Chinese cities start tightening entry measures against South Korean and other foreign visitors.

Feb. 25, 2020: China’s foreign ministry expresses support for cooperation with South Korea and Japan on fighting the coronavirus.

Feb. 26, 2020: ROK Deputy Foreign Minister Kim Gunn and PRC Ambassador to South Korea Xing Haiming meet in Seoul.

Feb. 27, 2020: Foreign ministers Wang and Kang hold telephone talks.

Feb. 28, 2020: ROK education ministry announces a cooperation agreement with China to advise students against returning to school in each other’s countries.

Feb. 28, 2020: ROK foreign ministry announces that South Korea will provide about half its promised $5 million worth of aid to China.

Feb. 29, 2020: ROK justice ministry indicates that 42 followers of the Daegu-based Christian sect Shincheonji are presumed to have entered the country from Wuhan over the last eight months.

March 2, 2020: North Korea fires what appears to be two short-range ballistic missiles into the East Sea. China’s foreign ministry calls for dialogue.

March 3, 2020: Moon declares “war” against the coronavirus.

March 3, 2020: US Treasury Department sanctions two PRC nationals linked to a North Korean state-sponsored cyber group.

March 8, 2020: North Korea test-fires short-range projectiles into the East Sea.

March 11, 2020: WHO calls COVID-19 a pandemic, and identifies China and South Korea as countries with “significantly declining” cases.

March 12, 2020: China Cultural Center in Seoul organizes online educational and cultural activities.

March 13, 2020: China and South Korea hold their first working-level video conference under a new inter-agency mechanism led by the foreign ministries.

March 14, 2020: Xi sends a message of support to Moon.

March 16, 2020: Seoul protests Beijing municipality’s March 15 decision to quarantine incoming travelers at designated facilities at their own expense.

March 17, 2020: Foreign ministries of China, ROK, and Japan hold conference call on coronavirus cooperation.

March 18-19, 2020: State media reports Chinese provincial donations for coronavirus relief.

March 20, 2020: North Korea fires two projectiles presumed to be short-range ballistic missiles toward the East Sea.

March 20, 2020: PRC, ROK, and Japanese foreign ministers hold a videoconference.

March 25, 2020: A Chinese military plane enters South Korea’s air defense identification zone.

March 27, 2020: ROK foreign ministry calls in PRC Ambassador Xing Haiming for a meeting with Deputy Foreign Minister Kim Gunn after Beijing’s March 26 announcement on temporarily suspending the entry of foreigners.

March 28, 2020: North Korea fires what appear to be two short-range ballistic missiles toward the East Sea.

Apr. 14, 2020: North Korea fires what appear to be cruise missiles and air-to-ground missiles into the East Sea on the eve of Kim Il Sung’s birthday anniversary and South Korea’s general elections.

Apr. 14, 2020: ASEAN+3 partners hold a Special Summit on COVID-19 Response via video.

Apr. 15, 2020: General Association of Koreans in China celebrate Kim Il Sung’s 108th birth anniversary.

Apr. 15, 2020: ASEAN+3 leaders adopt a joint statement on coronavirus cooperation.

Apr. 15, 2020: General Association of Koreans in China celebrate Kim Il Sung’s 108th birth anniversary.

Apr. 17, 2020: ROK Vice Foreign Minister Cho Sei-young and PRC counterpart Le Yucheng hold videoconference. ROK Industry Minister Sung Yun-mo and PRC counterpart Zhong Shan hold a videoconference.

Apr. 17, 2020: The China Tourism Office in Seoul and Shandong Provincial Department of Culture and Tourism organize an online exhibition.

Apr. 20, 2020: The ROK Consulate General in Wuhan resumes full operations.

Apr. 23, 2020: A CCP International Liaison Department senior official reportedly leads a delegation to North Korea amid speculation over Kim Jong Un’s health.

Apr. 27, 2020: ROK Vice Foreign Minister Kim Gunn and PRC Ambassador Xing Haiming meet in Seoul.

Apr. 27, 2020: The Palace Museum and China Tourism Office in Seoul jointly launch an Online Spring Forbidden City Photo Exhibition.

Apr. 27, 2020: China’s foreign ministry indicates that China has sent coronavirus testing kits to North Korea.

Apr. 29, 2020: Director-general talks between PRC and ROK foreign ministries reach an agreement to implement fast-track entry for each other’s business travelers from May 1.

May 1, 2020: Two chartered flights depart from Seoul with the first group of Korean high-tech workers returning to Wuhan.