Articles

While inter-Korean relations saw a fraught—even explosive—May-August reporting period, US relations with South Korea and North Korea settled into a holding pattern commingling frustration, disappointment, occasional bared teeth (from North Korea), and frequently forced smiles (from South Korea). Washington and Seoul failed to reach agreement on troop burden-sharing, an issue weighing down the US-South Korea alliance. Meanwhile, US-South Korea joint military exercises remain scaled-down, in part due to COVID-19, even as South Korea is committing to greater capabilities for its own defense. Regarding alliance coordination on diplomacy with North Korea, the administrations of Donald Trump and Moon Jae-in continue to try to mask obvious differences in prioritization of engagement for reconciliation and pressure for denuclearization. Ties between Washington and Pyongyang have stalled such that even talking about talking makes news. And in the background, Kim Jong Un’s regime continues to build up and improve its nuclear weapons program and missile arsenal.

Overall, US relations with the two Koreas are in a wait-and-see mode, with all three governments delaying significant steps until after the November US presidential election.

US-North Korea—Double Talkin’ Jive

The US and North Korean governments had no publicly known official interactions between May and September. The Trump administration has been fixated on the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic fallout, heightened strategic rivalry with China, and the November US presidential election campaign. In North Korea, activity in 2020 has been inwardly focused and relatively opaque even by its standards, as it has largely closed its borders with its primary trade and strategic partner, China, to limit its exposure to the novel coronavirus (in-country cases of which it has only reluctantly, and dubiously, intimated). Pyongyang has also assiduously attended to domestic concerns: making rare public admission of economic policy failures, dealing with flooding (prompted by heavy rains), re-shuffling political/party posts, and readying major construction projects for the October 75th anniversary of the founding of the Worker’s Party of Korea (WPK). Kim Jong Un’s health has remained a background issue. The biggest exception to Pyongyang’s inward focus was a dizzying July 10 statement by Kim Yo Jong (Kim Jong Un’s sister), who assailed the asymmetric value of US-North Korea summits (benefiting Trump more than Kim), lauded the positive relationship between the two leaders, and made a veiled threat that Washington should avoid antagonizing Pyongyang into an unpleasant “October Surprise.”

As noted in the previous reporting period, May began with Kim’s return to the public eye after weeks of absence and rumors regarding his wellbeing. President Trump responded by tweeting well wishes, saying that it was good to see Kim “back, and well!” This was followed by another set of relatively long periods in which Kim was not publicly depicted, and although he has since chaired high-level party meetings, reports of his “delegation” of some authority to others in the regime inner circle, notably Kim Yo Jong, have sustained speculation about his rule.

If Trump’s sentiments were aimed at prompting negotiations with North Korea, they failed. Throughout the summer Pyongyang and Washington failed to move beyond talking about talks. If the purpose was to support the façade of bonhomie between Trump and Kim to forestall potential provocations and keep open the door for future diplomacy, however, the results appear better. North Korea’s expressions of hostility—Kim Yo Jong’s May missives, the demolition at the inter-Korean liaison office, threatening to militarily occupy the DMZ—were directed more at Seoul than Washington. Advanced artillery and short-range ballistic missile launches, which had been regular events in 2019 and into spring 2020, were not repeated in the summer, and at points both the US and North Korea hinted at the future possibility of resumed talks.

Figure 1 An explosion at the inter-Korean liaison office. Photo: WSJ

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said on July 9 that he was “very hopeful” talks on North Korea’s denuclearization could take place, a little more than a month after he reaffirmed that denuclearization remained the objective. Other officials echoed these calls, and in the following month Pompeo’s boss said much the same, blaming uncertainty surrounding the November election from keeping additional talks, culminating in a deal, from occurring. “North Korea, we’re doing fine,” Trump said. “We’re doing fine with everything. They’re all waiting now to see.”

Two weeks later, Trump made a case for re-election by saying that Kim, along with Chinese Communist Party Chairman Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin, were all “world-class chess players” with whom he developed a rapport, but that his election opponent, former Vice President Joe Biden, could never contend with them. At moments over the summer Trump declared that his 2016 election was all that had prevented a war with North Korea. In July word leaked to the American Conservative that Trump administration insiders were hoping to reach a deal before the election.

Much commentary in recent months has cast doubt on the Trump administration’s ability to achieve (or even interest in) a substantive deal, rather than settling for the optics of détente. The status quo allows Trump to claim success—earned or not—in the form of North Korea’s moratorium on nuclear and long-range missile testing. And US voters are notorious for discounting foreign policy in presidential elections, so any deal brokered by the Trump administration to boost his election would have to be significant. Based on the signals from North Korea since Kim Jong Un’s resurfacing, Pyongyang intends to drive a hard bargain, and is nearly unmovable on its nuclear deterrent. This state of affairs buttresses the Trump administration’s political choice to rest on its ostensible laurels and softpedal the North Korea dossier until after the Nov. 3 election.

The Kim regime faces a similar question: does it want a real deal (achieved either opportunistically via exploiting US election season, or, more likely, after November), or is it content with the image of a détente and testing pause, while quietly building up its nuclear arsenal and attempting to ensure economic survival in the face of sanctions (via physical and cyber-enabled sanctions evasion) and COVID-19? Questions about regime intention are always difficult, especially as concerns Pyongyang, and that is even more the case currently, as the Kim regime is facing numerous, simultaneous challenges whose valence for regime preferences for external action is ambiguous. It requires a lot of bandwidth to improve a difficult domestic situation by balancing a focus on internal governance issues with reinforcement of national pride in possessing nuclear weapons, so delaying tricky diplomacy with a distrusted interlocutor facing potential political transition seems sensible. Some short-term solutions to domestic (especially economic) problems could take a path of least resistance, however, through nuclear diplomacy with the prospect of sanctions relief.

This ambivalence was on display throughout the summer. Kim—having disappeared for another three weeks following his May 1 reemergence—stepped back into the public eye on May 24 to convene a Central Military Commission (CMC) meeting focused on increasing strategic nuclear deterrence. A follow-up CMC meeting in July did not explicitly discuss nuclear weapons, but Kim told participants repeatedly that “bolstering a war deterrent of the country” would remain a priority, A week later, in an address marking the 67th anniversary of the Korean War armistice, he called nuclear weapons a “reliable, effective” deterrent that could prevent a second war. A July Politburo meeting chaired by Kim was dedicated to improving measures to prevent COVID-19. The meeting featured criticism of some officials’ response to the pandemic, implicitly indicating failure to keep the coronavirus out of North Korea. Certainly it indicated a regime preoccupied by an internal threat. That sense was reinforced in late August, when Kim called a WPK Central Committee meeting that produced both a rare public admission of the failure of recent (2016-2020) economic planning, and a scheduled 8th Party Congress for early 2021.

Figure 2 North Korean leader Kim Jong Un gives an address marking the 67th anniversary of the Korean War armistice. Photo: Reuters

If Kim said little about relations with Washington, senior officials acknowledged diplomatic stalemate while sending bi-valent messages regarding the use-value of negotiations with the US. In mid-June, two high-ranking North Korean officials threw cold water on the prospects for talks. Kwon Jong Gun, director general of the American affairs department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, responded to a US statement of disappointment with North Korea cutting communication lines with the South by warning against US intervention in inter-Korean disputes, claiming the result would be a “hair-riser” during US elections. The next day, Foreign Minister Ri Son Gwon vowed North Korea would build a reliable force to cope with long-term military threats from the US. Notably, instead of issuing a denunciation of “US imperialists” or “Washington,” Ri explicitly criticized the Trump administration, reiterating the notion that the administration’s calculus is largely driven by high-profile, low-substance summits that primarily look good for re-election campaigns. “In retrospect, all the practices of the present US administration so far are nothing but accumulating its political achievements. Never again will we provide the US chief executive with another package to be used for achievements without receiving any returns.”

A month later Kim Yo Jong—to whom brother Kim has reportedly delegated some power, including perhaps heading the powerful WPK Organization and Guidance Department (OGD)—chimed in with a multifaceted commentary, adumbrated above. Apparently acting both to increase her profile and as a mouthpiece for the North’s dissatisfaction with the South in June, Kim’s younger sister released a lengthy statement through the state wire service, KCNA, in which she expressed doubt about a summit, saying this would benefit the US almost exclusively and give little benefit to the North. “Serious contradiction and unsolvable discord exist between the DPRK and the US,” she said. “Under such circumstances, I am of the view that the DPRK-US summit talks is not needed this year and beyond, and for our part, it is not beneficial to us unless the US shows decisive change in its stand.” She did not close the door entirely on a meeting, saying “a surprise thing may still happen, depending upon the judgment and decision between the two top leaders.”

Any agreement the two sides reach between now and November—or beyond—does not appear as though it will include North Korea abandoning, or meaningfully downsizing, its nuclear arsenal. Consequently, regardless of whether Kim and Trump hold another summit, the US remains committed to a comprehensive pressure campaign against North Korea’s nuclear weapons program. Prior international and US sanctions remain in place, while on May 28 the US Justice Department indicted 33 North Koreans—including executives of the state-owned Foreign Trade Bank—on charges of facilitating $2.5 billion in illegal payments for Pyongyang’s nuclear weapons and missile program. The US government is also reportedly seizing 280 cryptocurrency accounts linked to North Korean hackers who stole and laundered millions of dollars as a part of sanctions mitigation.

In mid-June US B-52H strategic bombers were spotted near the Korean Peninsula on two separate occasions during a period of high inter-Korean tension following Pyongyang’s destruction of the Kaesong inter-Korean liaison office. On July 20, a US Air Force RC-135W Rivet Joint flew over South Korea to reconnoiter North Korea, possibly looking for the enhanced “war deterrent” Kim had mentioned just prior at a CMC meeting. In late August, before the start of US-South Korea joint military exercises, a detachment of US strategic bombers (four B-1Bs and two B-2s from the US and US Naval Support Facility Diego Garcia) was joined by a squadron of fighters (including F-35s from the aircraft carrier USS Ronald Reagan and F-15s from Japan’s Air Self-Defense Force) in crossing over the Korean Strait as a part of combined air drills. Beijing was likely the primary target of this action underlining US-led alliance force projection capabilities, but INDOPACOM’s statement clearly indicated that Pyongyang was also an intended recipient of the message.

Figure 3 US strategic bombers and a squadron of fighters cross over the Korean Strait. Photo: INDOPACOM

On the diplomatic front, US Assistant Secretary of State and Special Envoy for North Korea Stephen Biegun visited Seoul in July, where he made efforts to underscore the strength of the US-South Korea alliance and reiterated that the US is prepared to re-enter denuclearization talks with North Korea. A month later, continuing with the same basic message, US Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs David Stilwell, speaking during the 33rd US-ASEAN Dialogue, said North Korea “must halt provocations, abide by its obligations under the UNSCRs, and engage in sustained negotiations” to achieve fully verified denuclearization. In late August at a security forum, Defense Secretary Mark Esper reiterated a call for negotiations with the North, while emphasizing denuclearization as the objective. Meanwhile on September 1 the US State Department published an industry advisory directed at constraining North Korea’s missile programs by clearly reminding companies across the globe of the consequences for sales (even unintentional) to Pyongyang of missile-related (and dual-use) technology and materials.

US-South Korea—Estranged, or Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door?

US-South Korea alliance relations reached an absurd low point in early 2020, with the US ambassador to Seoul accused of Japanese sympathies because of his mustache and Trump belittling a South Korean film’s Oscar win. More substantively, Washington continued pressing outrageous demands in negotiations over troop cost burden-sharing under the Special Measures Agreement (SMA).

The May-August period did not plumb such depths, but the alliance is still strained. SMA negotiations are unresolved, the US has sent signals that troop levels may decrease, Trump’s disregard for Moon in particular and South Korea in general remains, Seoul and Washington have misaligned priorities on North Korea policy, and US-South Korea joint military exercises continue to be reduced and modified (partially due to policy choice, partially due to COVID-19) such that “conditions-based” remanding of wartime operational control of the military (OPCON transfer) to South Korea is at risk of delay. Behind-the-scenes accounts suggest barely concealed bitterness toward the White House within the Moon administration (whose reshuffling of senior aides has brought to power figures with a history of latent anti-Americanism dating from the 1980s). On the positive side, rows over trade between Washington and Seoul have receded, and Moon’s Blue House has committed to a significantly growing budget for high-end weapons and defense systems (including purchases from the US). One also notes that despite the general unease in the alliance caused by mutual disdain at the highest levels, popular and institutional (e.g., diplomatic corps, military) support girding the US-South Korea alliance in both countries is resilient, so far preventing the worst instincts of decision-makers from becoming reality.

The SMA negotiations remain deadlocked almost certainly due to Trump’s transactionalist fixation on financial cost-sharing and misunderstanding of the role and value of alliances in the maintenance of international order. James DeHart, former US State Department envoy for cost-sharing negotiations with South Korea, reportedly had a deal ready in April, but Trump refused it and ordered negotiations to continue. DeHart’s replacement, Donna Welton, received her appointment as chief negotiator in August, and is tasked with extracting higher payments from Seoul for the stationing of US troops on the Korean Peninsula, as well as for temporary deployment to South Korea of off-peninsula assets.

Although Washington has reduced its extortionate demand from late 2019 (ca.$5 billion annually), the current figure (supposedly $1.3 billion) is still a 50% increase over the amount agreed ($860 million) in the previous SMA. Seoul’s counteroffer is a 13% increase (ca. $975 million). This is a substantial, albeit bridgeable, difference. That said, the US is incentivized to push for the higher figure as a message to Japan, which will soon enter similar negotiations with the US. Beyond the monetary amount, there are also questions about the duration of the agreement (Seoul wants to lock-in multi-year SMAs as was the case before the 2019 stopgap agreement), and whether Seoul will be amenable to expanding areas of burden-sharing, such as payment for rotation of strategic assets (a burden-sharing metastisization that Seoul has so far avoided by tying it to renegotiation of the SOFA, in which the US has no interest). Seoul is content to run out the clock on the Trump administration, assuming a Biden White House will make more reasonable demands. If Trump wins re-election, Moon will likely adjust expectations regarding what constitutes an acceptable negotiation outcome. Regardless, the SMA issue will continue to cause friction in the alliance in the near term.

Looming in the background, the biggest potential negative knock-on effect of SMA discord is how it is linked to Trump’s threat of troop reductions on the peninsula. Indeed, there is well-founded worry that SMA disagreement gives Trump a policy-based excuse to scratch his anti-alliance itch and reduce US troop numbers in South Korea without a strategic plan. Seoul is concerned about this, but so is a bipartisan coalition in Washington. Starting in 2019 the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) set the lower bound for US troop levels in South Korea at 22,000, absent certification from the Defense Secretary that drawdown below that level would not adversely affect US national security. The 2020 and 2021 (draft) NDAAs tighten restrictions on drawdown, with the latter setting the floor at 28,500 (the current deployment level) and requiring a more stringent Pentagon certification process, including consultation with South Korea. Nonetheless, given Trump’s proclivity to violate institutional guardrails, a behavior likely to be more unrestrained post-re-election, these bureaucratic measures are hurdles not barriers.

US-South Korea joint exercises have also faced difficulties. Combined exercises have been delayed or reduced (even cancelled entirely in spring 2020), either as a policy choice (reflecting Trump’s lack of enthusiasm for “expensive wargames,” and the Moon administration’s desire not to aggravate North Korea) or due to COVID-19, which has infected soldiers in both militaries. The US and South Korea carried out annual computer-simulated Combined Command Post Training (CCPT/CPX) exercises during the summer, but even this routine event had thorny implications. The most recent combined exercises were reduced enough to prevent a Full Operational Capability (FOC) test, a necessary milestone in South Korea’s retaking of OPCON. News of the delayed FOC was followed shortly by reports that Gen. Robert B. Abrams, the commander of USFK/CFC/UNC, submitted to the Blue House enhanced criteria for OPCON transfer, increasing the METL (Mission Essential Task List) by 61 items (now totaling 155). This is likely to push back OPCON transfer beyond the 2022 deadline that the Moon administration had set.

Not all was gloomy in the US-South Korea alliance, however. At the end of May, Trump announced that the G7 summit, which the US originally planned to host in June, would be delayed by several months. Furthermore, he said that the present G7 membership “does not properly [represent] what’s going on in the world” and that more countries, including South Korea, would be invited to attend. On June 1, South Korean President Moon Jae-in said he would accept Trump’s invitation. This invitation was not met with universal approval; Japan has objected to Seoul’s participation and Germany opposes the addition of 4-5 more members, as Trump has proposed, saying that a “G11” or “G12” is unnecessary given the G20. Chinese state media has also warned South Korea about participating in a format it sees as designed to contain Beijing. However, as of mid-August, the US was still reportedly in communication with Seoul on the summit, and South Korea had promised to fulfill the duties of attendance.

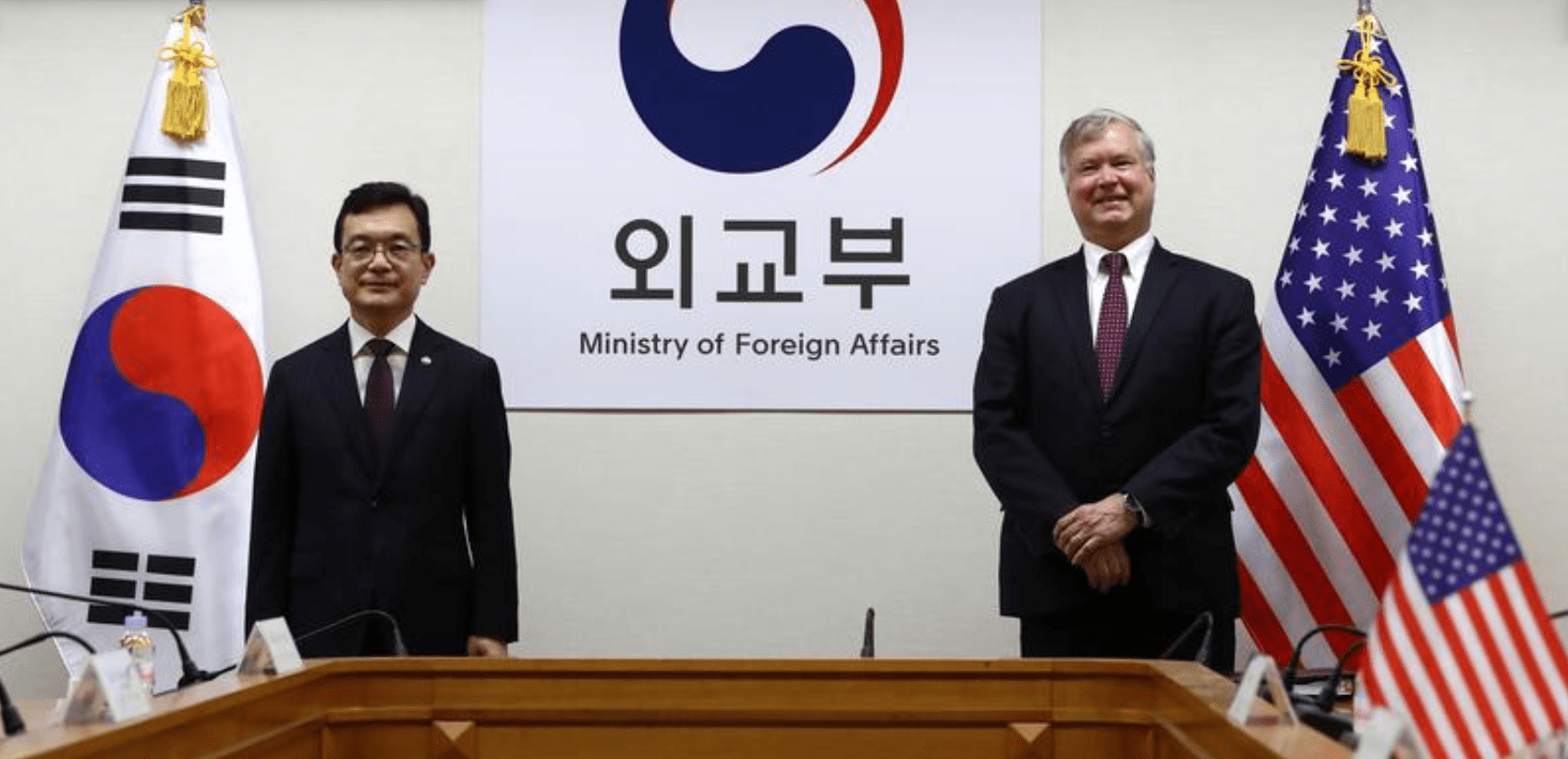

Also on the diplomatic front, the US point man for the Korean Peninsula, Stephen Biegun, visited his South Korean counterparts in July to coordinate on alliance politics and North Korea policy; he followed that up with a productive discussion with Lee Do-hoon, Seoul’s envoy to North Korea. Trump even found kind words for South Korea—or at least the renegotiated US-South Korea FTA—during the Republican National Convention in late August.

Figure 4 South Korean First Vice Foreign Minister Cho Sei-young meets US Deputy Secretary of State Stephen Biegun in Seoul. Photo: Reuters

Meanwhile Seoul is demonstrating impressive bona fides in improving its military capabilities. The announced 2021 defense budget will rise to $44 billion (+5.5% year-on-year), a record high. This would be the first installment of a 2021-2025 defense budget cycle that the Moon administration plans to total $235 billion, much of which is for military modernization, procurement, and research-and-development. In that vein, summer 2020 witnessed the announcement of several big ticket items, including the purchase of 40 additional F-35s slated for deployment on a planned light aircraft carrier. South Korea is also upgrading its ISR capabilities. After an initial launch—executed by SpaceX—of a military satellite for surveilling North Korea, Seoul has negotiated with the US the removal of solid-fuel restrictions for its own space launch vehicles, which will allow it to more economically place military satellites. These ambitions are advancing as a new South Korean Minister of National Defense (Suh Wook) and chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (Won In-choul) are taking up their posts. Time will tell if they manage to shepherd these procurement programs—which are important for OPCON transfer—toward completion.

Finally, the US-South Korea relationship—and by extension the alliance’s approach to North Korea—also received context when former Trump National Security Advisor (NSA) John Bolton published an account of his time working with the president. No party was flattered by Bolton’s description of Korean Peninsula diplomacy. Although The Room Where it Happened, published in late June, has an unreliable narrator with an ax to grind, critics of current relations between Washington and Seoul, and their feckless, superficial, and/or self-interested coordination on North Korea, had confirmed a lot of their suspicions. The Trump and Moon administrations were nonplussed and embarrassed.

Bolton claims that the Blue House was naïve (or possibly duplicitous) in establishing unrealistic expectations concerning denuclearization, which led to dashed hopes all around (and perhaps to the North’s recent hostility). Bolton’s portrayal of President Moon focuses on his reeking desperation to be visible at momentous occasions with Trump and Kim, most notably at their DMZ meeting in June 2019. Seoul responded in anger at the substance of Bolton’s claims (calling them “distorted”) and with aggrievement at the process foul—secret leader conversations were revealed (arguing it “violates the basic principles of diplomacy”). The Trump administration denied Bolton’s version of events (Trump called Bolton a “disgruntled boring fool who only wanted to go to war”), but distrust and tension between Washington and Seoul were amplified.

Bolton’s revelations on the North got the most attention, however. The former NSA asserted that Trump met Kim at the Singapore summit in 2018 because he considered it “great theater,” complimented Kim as a “really smart … a very good person, totally sincere, with a great personality,” and “preened” when Kim said he had demonstrated courage by coming to Singapore. Trump, Bolton continued, was happy to sign a substance-free communiqué in Singapore because of his greater concern with optics. This, however, led to mistaken impressions on the North Korean side, as Kim believed there would be “action for action,” with the US rolling back sanctions as North denuclearized in phases. Then, in the ill-fated Hanoi summit, Bolton writes that Trump, irritated by his former lawyer Michael Cohen’s testimony before Congress, chose to “walk away” rather than give the North Koreans a small deal that would not make for a big story.

Assessment and Strategic Picture: Welcoming Either Biden to the Jungle, or Trump’s Appetite for Destruction

US relations with the two Koreas are an uneasy holding pattern leaving critical matters in limbo. Existing dossiers—SMA negotiations, US troop levels on the Korean Peninsula, international sanctions, and North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs—have worsened with studied inattention. Failure to agree on US-South Korea alliance cost-sharing has produced bad publicity for the US, and fed Trump’s desire to reduce US troop levels on the Korean Peninsula. For the US, there may be a need to rethink US force posture in light of changing power dynamics in the Indo-Pacific, but a strategic perspective and approach are necessary, not presidential pique over costs. China has used Korean Peninsula diplomatic stasis to lessen sanctions enforcement. North Korea has continued producing (and presumably improving) nuclear weapons and delivery systems, albeit at the high price of economic stagnation.

These areas should receive stimulation after the November US presidential election. How that impulse is transmitted depends on which candidate wins. If Biden unseats Trump his party has pledged to counter North Korea by strengthening regional alliances, including with South Korea, which could thus expect a more accommodating US on burden-sharing and other issues. This would remove some of the unpredictability surrounding Washington’s relationship with Seoul and Pyongyang since 2017. It would likely also mean Strategic Patience 2.0, which is unrealistic and destined to fail given North Korea’s nuclear arsenal improvement since the Obama administration. For a Moon administration that covets progress on inter-Korean reconciliation, Strategic Patience 2.0 would be a bitter exchange for a more predictable Biden White House.

How a re-elected Trump would manage the alliance—both per se and vis-à-vis North Korea—is both more and less clear. It is clearer in that Trump’s tendencies (e.g., alliance disparagement, transactionalism) and obsessions (trade balances, media coverage) are well-known and fairly fixed. It is less clear in that Trump revels in unpredictability. The prospect of a US troop drawdown would be real, with unknown (but likely negative) knock-on effects for regional stability, notably for the credibility of US extended nuclear deterrence.

Finally, whoever is inaugurated as US president on January 20, 2021 will have a tough row to hoe on two strategic issues. The first is convincing South Korea to commit to an active Asia-Pacific policy line that is in consonance with—if not part of—the Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) concept, which is led by the US, Japan, and Australia, and supported by other regional states. As a “lynchpin” ally of the US, South Korea’s absence is noticeable. The reason, of course, is China, which objects to FOIP and whose likely pressure on South Korea, were it to align its Asia-Pacific regional policy with that of the US, is dissuasive. This is symptomatic of the second, larger strategic challenge the US has with respect to the Korean Peninsula: how should it be integrated—both in terms of the alliance with the South and diplomacy with the North—into the larger China-focused rivalry in a structurally dynamic Indo-Asia-Pacific? Whether Biden or Trump, this bracing question awaits the election winner like a cold November rain.

Chronology by Pacific Forum Korea Foundation Fellow Kangkyu Lee.

May 3, 2020: North Korean soldiers fire at a South Korean guardpost across the DMZ, prompting South Korean retaliatory fire with no damages or casualties, in the first breach of 2018 inter-Korean military pact.

May 4, 2020: Pompeo reaffirms that denuclearization remains key US strategic goal following North Korean leader Kim’s public reappearance.

May 4, 2020: North Korean defectors-turned South Korean assemblymen Thae Yong-ho and Ji Seong-ho apologized for “rash, careless” remarks confirming Kim’s public disappearance.

May 7, 2020: North Korean military representative says South Korean military drills were a “grave provocation” and violated inter-Korean agreements.

May 7, 2020: Kim Jong Un extends greetings to Chinese President Xi Jinping, congratulating him on a successful COVID-19 response.

May 10, 2020: South Korean President Moon Jae-in, in 3rd annual address to nation, says communications “not smooth” with North Korea, expressing hope for cooperation over coronavirus.

May 24, 2020: Kim Jong Un, in first appearance in 20 days, convenes Central Military Commission meeting focused on increasing strategic nuclear deterrence capabilities, mentioning nothing on inter-Korean activity.

May 26, 2020: UN Command concludes that both North and South Korea violated 1953 armistice agreement during exchange of fire following multinational special investigation.

May 26, 2020: US Justice Department indicts 28 North Koreans with facilitating $2.5 billion in illegal payments for Pyongyang’s nuclear weapons and missile program.

June 1, 2020: In phone call Moon says he would accept Trump’s invitation to G7 summit.

June 4, 2020: Kim Yo Jong, sister of North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, threatens to withdraw from inter-Korean military agreement and exchange projects over anti-Pyongyang leaflet activity.

June 4, 2020: South Korean Ministry of Unification releases statement denoting suspension of leaflet activities as a risk to inter-Korean cooperation.

June 7, 2020: Kim Jong Un convenes Politburo meeting of Workers’ Party concerning economic self-sufficiency.

June 8, 2020: North Korean Central News Agency says the country will cut all inter-Korean communication following order of Kim Yo Jong.

June 11, 2020: North Korean director general of the American affairs department of the Foreign Ministry Kwon Jong-gun warns the US against meddling in inter-Korean affairs, threatening a “hair-riser” during American elections.

June 12, 2020: North Korean Foreign Minister Ri Son Gwon vowed North Korea would build a reliable force to cope with long-term military threats from US, adding his country would “never again” provide US with “another package” that Trump could use to boast.

June 15, 2020: North Korean state media threatens South Korea with “severe punishment” over tepid approach to inter-Korean relations, saying “no need to sit face to face with the South Korean authorities.

June 15, 2020: North Korean People’s Army’s General Staff says it is prepared to move armed forces into DMZ.

June 16, 2020: North Korea blows up inter-Korean liaison office in Kaesong, followed by US urging North Korea from “further counterproductive actions.”

June 23, 2020: John Bolton, in his memoir, claims Trump thought the 2017 Singapore Summit with Kim Jong Un would be “great theater” and claims that Moon set unrealistic expectations concerning denuclearization.

June 24, 2020: Kim Jong Un suspends planned military action against South Korea in fifth meeting of the Seventh Central Military Commission of the Workers’ Party.

July 9, 2020: Pompeo says he is “very hopeful” about resuming denuclearization talks with North Korea.

July 9, 2020: Kim Yo Jong states that she doubts a US-North Korea summit will take place this year, adding that the summit would only serve to benefit the US.

July 16, 2020: Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan claims President Trump called South Koreans “terrible people” during private dinner, and questioned US protection of South Korea because “they don’t pay us.”

July 16, 2020: North Korean Pyongyang science research council claims it is developing vaccine for COVID-19.

July 19, 2020: South Korea says there were no discussions with US on US troop drawdown from Korean Peninsula following report that Pentagon provided troop cut proposals in March.

July 19, 2020: Kim Jong Un presides over Central Military Commission meeting of the ruling Workers’ Party concerning “bolstering a war deterrent of the country.”

July 20, 2020: US flies spy plane RC-135W Rivet Joint over South Korea to reconnoiter North Korea, possibly in reaction to recent Central Military Commission meeting.

July 20, 2020: Kim Jong Un rebukes officials during “field guidance” trip over “careless” construction of large-scale hospital planned for completion by October 10.

July 21, 2020: South Korea rejects UNC request to hold annual ceremony of Korean War armistice agreement at Freedom House in Panmunjom over coronavirus concerns and inter-Korean tensions.

July 25, 2020: North Korea declares state of emergency and places Kaesong under lockdown after allegedly finding South Korean runaway with COVID-19 symptoms in city.

July 27, 2020: South Korea confirms former North Korean defector secretly crossed back to North Korea, but cannot confirm if he had COVID-19.

July 27, 2020: Kim Jong Un calls his nuclear weapons a “reliable, effective” deterrent that could prevent a second war in address celebrating 67th anniversary of the Korean War armistice.

Aug. 3, 2020: Chicago Council of Global Affairs releases poll presenting that 90% of South Korean adults support the US-ROK alliance despite tensions over burden sharing.

Aug. 3, 2020: Donna Welton, former assistant chief of mission at the Embassy in Afghanistan, named new envoy for defense cost-sharing negotiations with South Korea replacing Jim DeHart.

Aug. 5, 2020: US Deputy Special Representative for North Korea Alex Wong says “US is ready” to negotiate on North Korean denuclearization.

Aug. 5, 2020: US Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs David Stilwell says North Korea “must halt provocations, abide by its obligations under the UNSCRs, and engage in sustained negotiations” to achieve fully verified denuclearization during 33rd US-ASEAN Dialogue.

Aug. 5, 2020: Trump says “…you don’t know that, and they have spikes,” during interview when asked if he thought South Korea was faking its COVID-19 statistics.

Aug. 5, 2020: Trump says North Korea would be “wanting to make a deal” if US presidential elections were not months away.

Aug. 5, 2020: US Defense Secretary Mark Esper remarks that expanding “lateral partnerships with South Korea and other Asian nations can help deter China’s ‘bad behavior’” during Aspen Security Forum.

Aug. 11, 2020: ROK Ministry of Defense releases $252.7 billion five-year defense blueprint including acquisition of light aircraft carrier and multi-tiered missile interception system.

Aug. 12, 2020: ROK Unification Ministry launches investigation into North Korean civic and defector groups.

Aug. 13, 2020: Kim Jong Un lifts lockdown on Kaesong, insisting on closed borders and rejection of international flood aid.

Aug. 18, 2020: US and South Korea began computer-simulated annual Combined Command Post Training (CCPT/CPX) exercises planned to run until Aug. 28.

Aug. 18, 2020: President Trump says Kim Jong Un is among “world-class chess-players,” adding “we get along.”

Aug. 19, 2020: Department of State says it regularly “coordinates on diplomatic efforts” with South Korea on inter-Korean affairs following US Ambassador to South Korea Harry Harris’ statement reaffirming importance of inter-Korean cooperation working group.

Aug. 19, 2020: Kim Jong Un says he will present a new five-year economic development plan at a Eighth Congress of the Workers’ Party in January 2021.

Aug. 20, 2020: Kim Jong Un reportedly delegates partial power to sister Kim Yo Jong, among other close aides.

Aug. 25, 2020: During speech on first day of Republican National Convention, Trump says he improved the 2012 US-Korea free trade agreement.

Aug. 25, 2020: South Korea reportedly to purchase 40 Lockheed Martin F-35 jets at the cost of $6.7 billion to be delivered by the end of 2021.

Aug. 27, 2020: Esper says the goal of “complete, verifiable and irreversible” denuclearization of North Korea hasn’t changed, reiterating diplomacy as “best path forward.”

Aug. 27, 2020: North Korean TV stations air footage of damage caused by Typhoon Bavi as Kim Jong Un emphasizes need to minimize damage at politburo meeting.

Aug. 28, 2020: US Department of Justice files civil forfeiture complaint against 280 North Korean-linked cryptocurrency accounts.

Aug. 28, 2020: North Korea broadcasts alleged encrypted spy message for first time on state-run Radio Pyongyang’s YouTube channel.

Aug. 31, 2020: US Forces Korea suspends training in Pocheon after a military vehicle driven by two US soldiers crashes into SUV killing four South Korean civilians.