Articles

After a months-long wait to see who would lead the US from 2021, both South and North Korea got an answer in November: Joe Biden. South Korea moved to forge ties with the incoming US administration, relieved at the prospect of a more conventional White House, yet anxious for it to adopt an approach to North Korea congruent with that of the Blue House. North Korea has stayed mum on Biden’s victory, reflecting its poor relations with the former vice president, a pause to recalibrate diplomatic expectations, and domestic issues that overshadow foreign policy in Pyongyang. The latter point is fitting, as it is also true of Washington. The early days of the Biden presidency will see domestic focus due to the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccine rollout, economic recovery, and the need to try to heal political and cultural divisions in the United States. That said, neither Korea can be neglected for long.

Election Fallout: Return of a ‘Serious Man’

As throughout 2020, the lead-up to the November election saw little discussion between the US and North Korea, though figures in the Trump administration promised that Trump’s re-election would spark a breakthrough. Even interactions between the US and South Korea were limited and restrained compared to earlier in 2020, when, for example, there were tough negotiations over troop burden-sharing under the Special Measures Agreement (SMA). Seoul and Pyongyang took a wait-and-see approach to US relations, knowing they could be dealing with a strikingly different interlocutor depending on the election results.

Early indications suggest South Koreans are relieved by Biden’s election, seeing him as one who takes traditional diplomacy seriously, but one who also recognizes changes that have taken place since the Obama administration. That said, the Biden White House is likely to have priorities toward Korea similar to those of previous US administrations, including Trump’s: maintaining high-quality economic ties and the military alliance with South Korea, while pressuring North Korea to cease and eventually roll back its nuclear weapons program. Additionally, the US relies on South Korea to improve inter-Korean relations, notably via Seoul’s proposals for joint economic projects and confidence-building measures, while Washington mixes sticks (sanctions, military deterrence) and carrots (potential sanctions relief) to try to advance denuclearization of North Korea. Over several decades this overall strategic approach to Korea has been successful in advancing the US-South Korea relationship; it has failed abysmally with respect to North Korea’s nuclear weapons development.

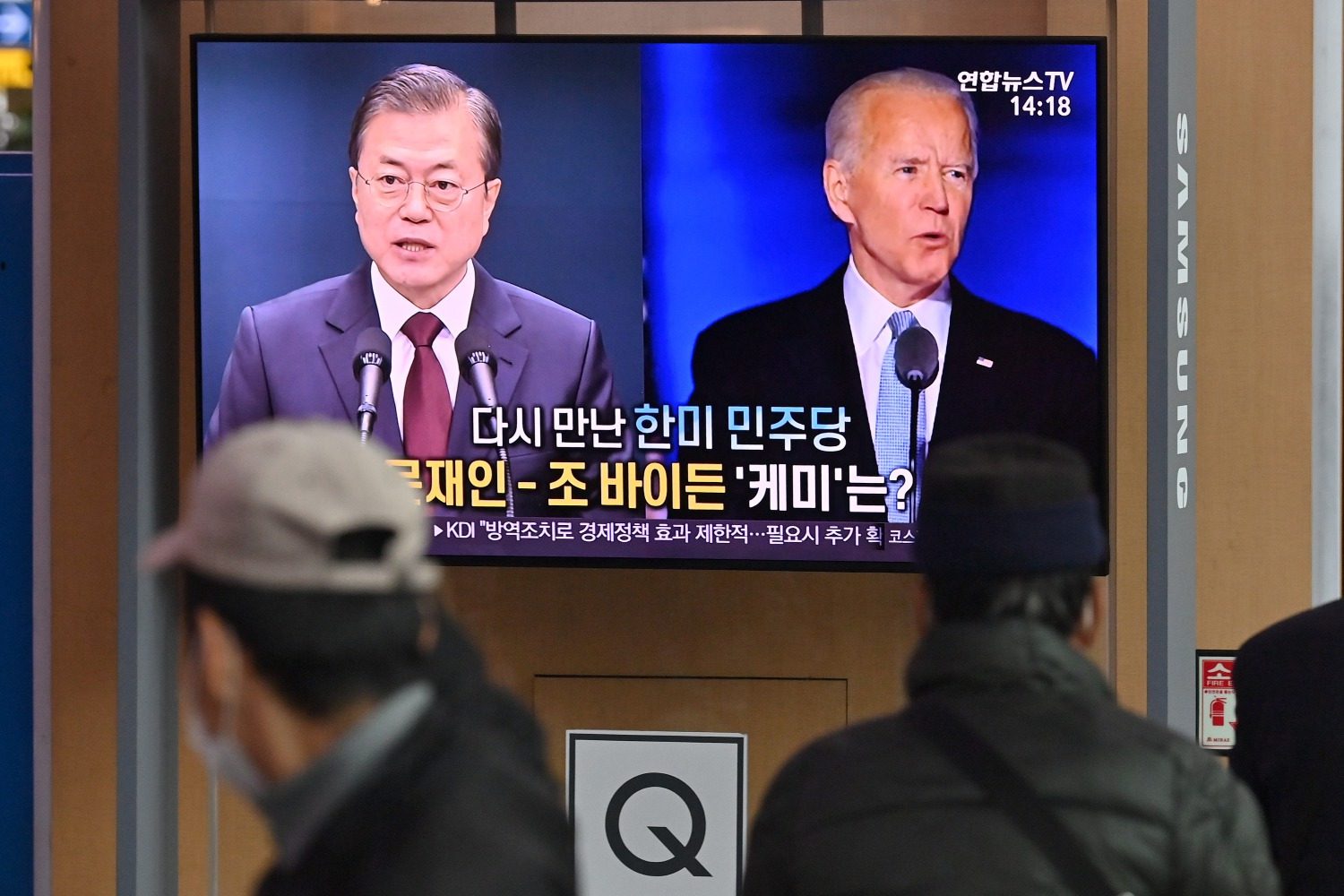

Figure 1 News coverage of the US presidential election at a Seoul railway station. Photo: AFP

What has changed under the Trump administration is not the fact that North Korea has continued to build out and improve its nuclear weapons arsenal, which happened under every US president since the 1990s, but rather that the US-South Korea alliance frayed as well. This was due to multiple factors—including missteps by South Korean President Moon Jae-in and an increasingly complicated regional environment for alliance management—but the overarching reason was the US administration. US-South Korea alliance degradation was a consequence of choices and priorities by President Trump, as well as his transactionalism and distaste for alliances in general. Worse still, this occurred during a period of rising strategic competition with China, which should have made the importance of US alliances, including with South Korea, even more marked.

Joe Biden, by contrast, is the walking definition of establishment centrism, and his administration’s foreign policy outlook prioritizes re-building US alliances to recover US international influence and compete more effectively with China both regionally and globally. The incoming White House also recognizes that improving US standing abroad requires addressing dramatic domestic challenges: COVID-19 mitigation and vaccination, economic recovery, and healing the political polarization and cultural division that have cleaved US society. This implies that the Korean Peninsula will not be an immediate focus for Biden.

When the time comes to turn to the Korean Peninsula, there will be a mix of familiar problems and new opportunities. The new administration inherits Trump’s refusal to give sanctions relief for the North ahead of serious concessions on its nuclear program. This is the orthodox US position. It is also one that has failed to prevent North Korean nuclear weapons proliferation and qualitative and quantitative improvement of its warheads and delivery systems. The establishment credentials of Biden and his foreign, security, and defense policy team indicate that his administration would tend to take a standard hardline approach to Pyongyang (more on this later). In late October he opened the door to meeting with Kim Jong Un, but only after drawdowns in nuclear capacity of the sort that North Korea has consistently rejected. Around the same time, he blamed Trump’s “friendship” with Kim Jong Un for blinding him to the growing threat of North Korea’s nuclear weapons and expanded missile arsenal. And while no one should expect a precise repeat of the Obama administration, it cannot be overlooked that Biden was its vice president, and that this administration tightened sanctions and disavowed proactive solutions to the North Korea conundrum after the Leap Day Deal debacle. That said, there is a small but growing community of North Korea experts in Washington arguing for shifting US nonproliferation policy toward North Korea to that of arms control, which may find more support in both Koreas. Even Biden’s nominee for secretary of state, Antony Blinken, has hinted at this possibility, if one reads between the lines.

Figure 2 President Moon Jae-in virtually delivers a speech to the United Nations General Assembly, urging the UN and the international community to formally end the 1950-1953 Korean War. Photo: Blue House

During the September-December period South Korean officials were straightforward about the approach to the North they hoped from Washington, regardless of which presidential administration would begin Jan. 20. On Sept. 22, Moon made a call for a declaration of the end to the Korean War at the 75th session of the United Nations General Assembly. In November, Director of National Security Suh Hoon urged a return to talks with North Korea. Five days later Foreign Minister Kang Kyung-hwa reaffirmed the Moon government’s commitment to reaching a peace regime. The chairman of Moon’s Democratic Party, Lee Nak-yon, went so far as to call on Biden to keep the deal Trump signed with Kim in Singapore in 2018. That the South has continued to push the issue, not only with the US but with China, suggests that Moon’s September UN statement was part of an effort to build international consensus.

Biden and Moon have reaffirmed commitment to working together on the North Korean nuclear issue, but that is only one task for the alliance. Some outstanding issues are relatively easy (e.g., US troop burden-sharing), others are fraught (US-South Korea-Japan trilateral cooperation), and still others are new and promising (growing the US-South Korea military alliance on space defense cooperation, or Seoul’s participation in a D-10 grouping to be inaugurated at the upcoming expanded G7). One of the key issues in the US-South Korea relationship will be how Seoul aligns its geostrategic/geo-economic/geopolitical approach to Southeast Asia, notably under the New Southern Policy, with Washington’s more muscular approach to the Indo-Pacific, which Biden has indicated he will continue.

However, given the rise in strategic competition with China and resulting complications in the regional strategic environment, managing relations with the two Koreas will require more than merely being nicer to Seoul on burden-sharing and restoring a less mercurial policy approach toward Pyongyang. Moon has high hopes for inter-Korean cooperation that have thus far been blocked by US-led sanctions, and Moon’s administration is hedging by signaling warmer relations with Beijing. The North continues to defy the US pressure campaign designed to stop its nuclear weapons program, and China’s lax sanctions enforcement renders this possible (despite the drop in North Korea-China trade due to COVID-19 border closures). It is a wicked problem to square the circle on US-South Korea relations, US-North Korea denuclearization efforts, and the US commitment to nonproliferation, all with a disruptive China in the background and a still-uncontained global pandemic.

US-South Korea: O Brother, Where Art Thou?

During the final trimester of 2020 the US-South Korea relationship, long predicated on mutual security and shared values, was in stasis. A lull is a normal, periodic consequence of the US presidential electoral cycle. The spectacle during this lull, however, was highly abnormal, as the Trump campaign and a significant part of the Republican party have engaged in an unprecedented attempt to overturn the presidential election. Certainly Trump’s refusal to concede to Biden put Moon—like most world leaders—in an uncomfortable protocol dilemma, as he was obliged to weigh how long to delay the traditional congratulatory phone call to the presumed president-elect. More substantively, US-led alliances, including with South Korea, have been girded by shared democratic values for decades, so a US political system with damaged rule-of-law would mean other countries would face a US partner of a different character.

Now, with the election decided for Biden, the Moon administration may be relieved, even if that relief is tinged with regret as Trump’s departure means a likely reduction of transformative possibilities for the Korean Peninsula. Trump’s unorthodox, personalized wheeling-and-dealing did conjure the occasional fleeting opportunity for a breakthrough in US-North Korea relations, with positive potential knock-on effects for inter-Korean relations. Moon seized those opportunities and tried to realize them, even if they ultimately stalled. This tantalizing set of opportunities, moreover, was accompanied by complications from the US side: extortionate SMA demands, harassment about the US-South Korea trade imbalance, subtextual threats of US troop withdrawals from the peninsula, and public and private denigration of the alliance in general.

Moon will not miss these headaches. Rather, at the leader and Cabinet secretary levels Moon and his senior officials will now have an experienced set of counterparts aiming to rebuild US alliance relations, even if South Korea as such will not likely be an immediate priority for the incoming White House. Thus the Moon administration will likely need to be patient in expectation that the Biden administration will turn to dealing with the Korean Peninsula.

Still, the Biden administration’s foreign policy team will get its chance to deal with Korea issues soon enough. At the highest levels, some of that team is already known: Antony Blinken as secretary of state, Lloyd Austin as secretary of defense, Jake Sullivan as national security advisor, Avril Haines as director of national intelligence, Katherine Tai as US trade representative, Linda Thomas-Greenfield as US ambassador to the United Nations. Personnel is policy, and these names (some of which require Senate confirmation) signal competence and centrist Democratic, establishment foreign policy and national security ideas.

It remains to be seen how that will translate into US policy on the alliance with South Korea, not only because events (especially unforeseen events) will drive policy, but also because most of the senior-level alliance managers responsible for or connected to the Korea portfolio are still unknown. As with every incoming presidential administration, there will be significant turnover, and staffing takes time. US Ambassador Harry Harris will vacate his post without a known successor, as will US North Korea envoy (and deputy secretary of state) Steve Biegun. One notes that South Korea also has a new North Korea envoy, Noh Kyu-duk, who replaced Lee Do-hoon in December. The incoming White House’s nominees for assistant secretary of state for Asia-Pacific Affairs and the assistant secretary of defense for Indo-Pacific security affairs are also unknown. The same is true for senior officials responsible for Asia and Korea at the National Security Council.

US-Korea stasis in the final trimester of 2020 meant pending issues saw little or no progress. In theory one of the easiest problems to solve is the impasse over the US-South Korea SMA, which became a problem largely due to exorbitant demands by Trump in late 2019 and throughout 2020. A stopgap burden-sharing arrangement was in force until Dec. 31, 2020. Given that negotiations throughout 2020 yielded no satisfactory compromise, in the middle of October USFK advised the South Korean government that current SMA funding will run out on March 31, 2021. This is not only a problem for alliance management reasons, but also has a political dimension, as SMA funding cut-off would furlough 9,000 South Korean contract workers for the USFK. However, signs indicate that the Biden administration will set the SMA contribution request at a manageable figure, which portends well for removing this thorn from the side of the alliance during the first half of 2021.

The military dimension of the US-South Korea alliance remains solid—with joint military cooperation, inter-operability, and trust at high levels—and little changed in that regard during the September-December period. Gen. Suh Wook, who became South Korean defense minister in September 2020, has met with his counterparts—US defense secretary Christopher Miller, and his predecessor Mark Esper, as well USFK/CFC/UNC Commander Gen. Robert Abrams, US Army Chief of Staff Gen. James McConville, and Adm. Philip Davidson, chief of US Indo-Pacific Command—to continue strengthening alliance military cooperation and strategize on countering North Korea and its nuclear program. Suh will soon have a new USFK/CFC/UNC commander with which to interact, as Gen. Abrams will finish his posting and be replaced by Gen. Paul LaCamera.

There are alliance sticking points, however. The combination of postponement and scaling-down of US-South Korea combined exercises—first due to Trump’s decision following the 2018 Singapore summit, and then due to precautions in light of COVID-19—have begun to erode joint military readiness. McConville has had regular contact with South Korean military leadership regarding strengthening alliance military cooperation, but stated in September that it is unlikely that full-scale exercises can resume before the end of the pandemic, which has led to numerous outbreaks among US and South Korean soldiers. The US has begun vaccinating USFK members in Korea, but South Korea has yet to do so. The Blue House has competing interests regarding a possible US request to resume full-scale combined exercises. On the one hand, a return to full-scale exercises is a sine qua non for the still-unresolved issue of transferring wartime operational control back to South Korea, a priority for Moon. On the other hand, Unification Minister Lee In-young hinted at reluctance to restart full-scale exercises if they were to impede inter-Korean relations, claiming in December that exercises “must not provoke” Pyongyang, a deferential attitude that likely rankles in both Washington and among the ranks of USFK.

In the September-December period, two nuclear-related issues continued to lurk in the background of the US-South Korea military alliance. First, Trump’s erratic commitment to the alliance and inability to halt North Korea’s nuclear program have cast doubt on US extended nuclear deterrence for South Korea. This has moved discussions of Seoul acquiring its own nuclear deterrent out of the political fringes and into the mainstream, as Kim Chong-in, leader of the main opposition party PPP (People Power Party), argued that South Korea would have to seriously consider developing nuclear weapons if North Korea did not denuclearize.

Second, and more likely to cause consternation, South Korea reiterated its plans to develop a nuclear-powered attack submarine, the fueling of which would complicate US nuclear policy toward South Korea in particular. In September, South Korean Deputy National Security Advisor Kim Hyun-chong went to Washington to ask the US to provide the nuclear fuel for the submarine’s reactors. Doing so would require re-negotiation of the US-South Korea Agreement of Cooperation Concerning the Use of Atomic Energy for Peaceful Purposes, which the US has no interest in doing. Seoul could pursue its own uranium enrichment program to produce reactor fuel indigenously, but this would be provocative, put Seoul crossways with Washington, and damage denuclearization efforts vis-à-vis Pyongyang.

Beyond bilateral alliance management issues, there are several regional challenges for the US-South Korea partnership. One US desideratum is improved US-South Korea-Japan trilateral relations—Blinken, the secretary of state nominee, has stated that mending South Korea-Japan relations will be one of his priorities. This will require finesse, as domestically there is little to be gained politically in Seoul or Tokyo from repairing fractured relations. It makes sense from a US perspective, however, as solid Seoul-Tokyo ties make more efficacious US regional strategy in the Indo-Asia-Pacific, especially in terms of countering both China and North Korea.

Although manageable—whether via 2+2 ministerial meetings, the Security Consultative Mechanism, or the US-South Korea working group established in September by South Korean Vice-Foreign Minister Choi Jong-gun—friction on the above dossiers is pre-programmed, as in a few other areas. To wit: the US under Biden will likely continue to prioritize a competitive China strategy implicating regional partners such as South Korea in areas such as trade/economics, technology (notably 5G), maritime security, cybersecurity, and human rights. Seoul is concerned about drawing the wrath of Beijing, particularly economically, and can be expected to continue to hedge where possible.

The North Korea dossier presents both peril and promise for Washington-Seoul relations. The Moon administration is seeking to advance diplomacy with Pyongyang, but the incoming Biden White House foreign affairs and security policy team has left North Korea off its list of priorities. Improved inter-Korean relations—which require coordination with the US—is Moon’s signature issue, but he has little to show for it even as his term is entering its last full year. Whether via the 8th Workers’ Party Congress or otherwise, Pyongyang will have its say, of course. One should not expect it to remain sidelined by Washington for long. A re-start of nuclear and/or missile testing would get the attention of the Biden team and move Pyongyang higher on the agenda. At the same time, a belligerent North Korea makes improved inter-Korean relations a more difficult sell for Moon.

US-North Korea: The Relationship That Wasn’t There

Little has happened at the highest levels of US-North Korea relations since early 2019. There has been, however, a quid pro quo equilibrium: North Korea continued its moratorium on testing long-range missiles and nuclear weapons that the US considers especially provocative, while the Trump administration stopped pushing for major new UN sanctions and downplayed human rights. At lower, bureaucratic levels the US continued efforts to restrain North Korea’s proliferation activities, which continued apace, and North Korean officials did not hesitate to denounce the US, although not Trump himself. US officials occasionally spoke of ongoing talks and possible breakthroughs, and both leaders spoke fondly of one another, keeping alive hopes of a deal if Trump was re-elected. Indeed, Kim was one of the world leaders to send his regards following Trump’s October COVID-19 diagnosis.

Between September and the end of December this trend continued. The US:

- Successfully prosecuted a company based in the British Virgin Islands, which pleaded guilty to laundering money for North Korean clients.

- Placed new sanctions on Iranian entities and individuals, with the justifications for doing so including the resumption of cooperation between Tehran and Pyongyang over long-range missile development.

- Called Pyongyang’s nuclear and missile programs a global threat after seeing North Korea’s new weapons—especially a new generation ICBM—at its October military parade.

- Issued a warning in late October over the North Korean hacking group Kimsuky, seemingly timed to deter interference in the upcoming election.

- Sanctioned two North Korea-linked enterprises operating in Russia, citing involvement in the exploitation of forced labor.

- Offered up to $3 million in funding for organizations working for North Korean human rights, a 25% increase over the State Department’s previous offering.

- Criticized China for “flagrant violation” of obligations to enforce international sanctions on North Korea, adding that the US would offer rewards up to $5 million for information about sanctions evasions.

- Placed new sanctions on six entities and four vessels related to North Korean sanctions evasion.

The Kim regime had little reaction to such measures, probably because its focus was on internal matters. North Korea is by all accounts in as difficult a position as it has been in 25 years. The only recent positive for North Korea was the October stealth military parade, in which it celebrated the 75th anniversary of its ruling party by displaying modern military equipment, including a new ICBM. The parade was a good show, but other than this international and domestic propaganda success, the situation in North Korea has become dire.

Figure 3 Military vehicles are seen during a parade to mark the 75th anniversary of the founding of the ruling Workers’ Party of Korea, October 10. Photo: KCNA via Reuters

Inclement weather, including severe flooding, left the North Korean leader concerned about typhoon recovery outside the country’s capital and in its mining areas. Worry over COVID-19 has loomed particularly large. Given the Kim regime’s decision to close the border with China for nearly all of 2020, Pyongyang’s licit trade with Beijing has shrunk to practically zero. The economic consequences are bordering on disastrous. North Korea has also warned citizens to stay inside to avoid so-called COVID-carrying “yellow dust,” and the virus threat was implied even when not mentioned, as it appears to have led to suspension of the mass games expected in October. Earlier that month Kim took the unprecedented step of weeping openly and saying he had failed to provide the people of the country with a better economy. The regime ordered an 80 day economic “speed battle”—much hated by North Koreans—to finish state development projects and boost economic productivity.

Under such conditions, it’s safe to say Kim’s priority is on avoiding domestic catastrophe and ensuring regime survival in the Hermit Kingdom. He even refrained from the usual New Year’s address, instead penning a solemn letter thanking North Koreans for their support in difficult times. This makes the outcome of the just completed 8th Workers’ Party Congress all the more critical, both as such and in terms of the signals it will send the Biden administration.

Kim’s opening Congress speech apologized for failure of the 2016-2021 five-year economic plan, vaguely referred to better relations with South Korea, and did not mention nuclear weapons. A new five-year economic plan was also announced at the Congress, although the details are still sketchy. Focus on prolonged autarky would suggest a continued shutdown of nuclear diplomacy with the US, as Kim would be betting that he can survive sanctions that might be lifted if an agreement were to be made. Beyond that signaling mechanism, the Biden administration’s Korea policy team will want to study the mix of focus on domestic (economics, technology, pandemic) vs international (e.g., China relations, military deterrence) issues, and what that might reveal about Pyongyang’s intentions toward Washington. Any openings toward improved inter-Korean relations will also be scrutinized for possibilities that they might allow Washington and Seoul to coordinate policies for renewed nuclear negotiations and steps toward a more peaceful and secure peninsula.

Conclusion: No Country for Old Approaches

Perhaps the biggest question is whether the Kim regime will engage in an act of hostility—nuclear or missile test, inter alia—to welcome the Biden administration and move Pyongyang up the agenda in Washington. This is a standard move from Pyongyang’s playbook, and one that has bedeviled the approach to Korea for most recent US presidents. North Korea had largely been silent about the US in the final six months of 2020, but at the 8th Party Congress on Jan. 9 Kim called the US North Korea’s “biggest enemy,” then announced a series of goals for increased military power, including missiles with strike capabilities of 15,000 kilometers, tactical nuclear weapons, ground or submarine-launched solid-fuel intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), plus hypersonic aircraft and a military surveillance satellite.

Had the silence of the second half of 2020 been a precursor to a fixed strategic plan, or a sign of strategic flexibility, perhaps waiting to see what would be produced by a review of North Korea policy by the Biden administration? The prevailing sense is that Kim will miss comrade Trump, whose unorthodox approach to negotiations failed to deliver sanctions relief, but at least made that prospect thinkable, even in the absence of significant denuclearization. That said, the US and North Korea continue to have divergent national interests, and how Kim initially reacts to a new US administration will set a path that will likely persist throughout Biden’s presidency.

Another important question is how much space Moon will have to facilitate dialogue along his preferred path. If North Korea chooses not to act provocatively early in Biden’s term, and gives him a chance to settle into the role and address the wreckage left over from America’s 2020 annus horribilis, it improves the chances of the US working with South Korea to find opportunities to reduce sanctions pressure. Yet Biden may not, as Trump did, disregard short-range missile tests of the sort North Korea carried out in 2019 and 2020, and may consider them provocations. With the US deeply divided, behavior that the US public considers threatening may not give Biden the political leeway necessary for a deal. In any event, by the time we revisit US-Korea relations in late spring, the pattern for US engagement with the Korean Peninsula may be set.

Chronology compiled by Pacific Forum intern Hanmin Kim

Sept. 1, 2020: A company based in the British Virgin Island pleads guilty to laundering money for North Korean clients.

Sept. 2, 2020: Documents reveal that North Korea is seeking millions of dollars in medical supplies for an upcoming Pyongyang general hospital project.

Sept. 3, 2020: Senior adviser Jared Kushner says President Trump will reach a breakthrough with North Korea if he is reelected.

Sept. 4, 2020: Satellite imagery suggests North Korea’s preparation for a submarine-launched ballistic missile at the South Sinpo shipyard.

Sept. 6, 2020: North Korea sends only low or mid-level diplomats to UN General Assembly meetings this year.

Sept. 7, 2020: UN chief urges North Korea to resume denuclearization talks with the US and the South.

Sept. 8, 2020: North Korean leader Kim Jong Un calls for an urgent recovery from typhoon damage.

Sept, 9, 2020: US Army chief Gen. James McConville says he doesn’t see full-scale ROK-US drills amid the coronavirus pandemic.

Sept. 11, 2020: US and South Korea agrees to launch a new working-level dialogue channel to discuss alliance matters.

Sept. 12, 2020: Kim inspects recovery work in a flood-hit area, according to North Korea state media.

Sept. 13, 2020: Deputy Secretary of State Stephen Biegun expresses Washington’s support for lasting peace on the Korean Peninsula at a regional security meeting.

Sept. 15, 2020: Secretary of State Mike Pompeo tells the Atlantic Council that US talks with North Korea remain ongoing.

Sept. 16, 2020: South Korean Minister of Unification Lee In-young visits Panmunjom, urging North Korea to implement agreements reached during the 2018 inter-Korea summit.

Sept. 17, 2020: Assistant Secretary of State for East Pacific and Pacific Affairs David Stilwell says that the US is not discussing the possibility of withdrawing troops from South Korea.

Sept. 18, 2020: USS Pueblo intelligence ship veterans file a lawsuit against North Korea, demanding compensation of up to $6 billion.

Sept. 19, 2020: North Korean defector is arrested trying to cross back into the DPRK.

Sept. 20, 2020: US announces new sanctions on Iranian entities and individuals, saying Tehran and North Korea have resumed cooperation on long-range missile development.

Sept. 21, 2020: Energy Secretary Dan Brouillette says the US “remains committed to addressing the threats posed by the nuclear programs of both North Korea and Iran” at IAEA.

Sept. 22, 2020: South Korean President Moon Jae-In calls for declaring an end to the Korean War at 75th session of the United Nations General Assembly.

Sept. 25, 2020: State Department condemns North Korea’s killing of a South Korean official and demands an explanation.

Sept. 26, 2020: State Department says North Korea’s apology over killing of a South Korean official is a “helpful step.”

Sept. 27, 2020: North Korea accuses South Korea of sending ships into its territory to find the body of the dead South Korean official.

Sept. 28, 2020: ROK President Moon apologizes to the South Korean public and the family of the official killed by North Korean troops.

Sept. 29, 2020: South Korean Coast Guard says that the South Korean official killed by the North Korean Navy sought defection to the North.

Sept. 29, 2020: Biegun says the US and South Korea discussed how to move the stagnated dialogues with the North.

Sept. 30, 2020: North Korea’s UN ambassador says North Korea has a “reliable and effective war deterrent for self-defense.”

Oct. 1, 2020: Kim Jong Un inspects a flooded village damaged by recent typhoons.

Oct. 2, 2020: Kim Jong Un sends a letter to President Trump, expressing his hopes that he would recover from the coronavirus.

Oct. 4, 2020: South Korean and US intelligence have spotted North Korea moving an intercontinental ballistic missile.

Oct. 4, 2020: Pompeo cancels a planned visit to South Korea.

Oct. 5, 2020: South Korea’s Unification Ministry calls on North Korea to respond to South Korea’s request for a joint investigation over the killing of a South Korean official.

Oct. 6, 2020: North Korea’s acting ambassador to Italy, who went missing in late 2018, reveals he lives in South Korea under government protection since last year.

Oct. 8, 2020: South Korea grants permission to private organizations to send $1.24 million in private aid to North Korea.

Oct. 11, 2020: South Korean government holds emergency National Security Council meeting after North Korea unveils a massive intercontinental ballistic missile.

Oct. 13, 2020: Kim Jong Un inspects a mining area in South Hamgyong province, which was recently hit by flooding and typhoons.

Oct. 14, 2020: Defense Secretary Mark Esper says North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs pose a global threat, after seeing North Korea’s new weapons at military parade.

Oct. 15, 2020: UN condemns North Korea’s unlawful killing of a South Korean government official in waters.

Oct. 16, 2020: South Korean National Security Adviser Suh Hoon says Seoul and Washington are on the same page over the initiative to declare the end of the Korean War.

Oct. 17, 2020: U.S. National Security Adviser Robert O’Brien sees a chance to resume denuclearization talks with North Korea around next summer Olympic games.

Oct. 19, 2020: Civilian tours of Panmunjom will reopen early next month after a year of suspension caused by the African swine fever, the Unification Ministry says.

Oct. 20, 2020: South Korean Defense Minister Suh Wook and Adm. Phil Davidson, commander of the US Indo-Pacific Command, discuss denuclearization of North Korea.

Oct. 21, 2020: South Korean Unification Minister Lee In-young says South Korea will keep seeking dialogue with North Korea for cooperation in railway linking.

Oct. 22, 2020: North Korea appears to have suspended gymnastic shows scheduled for this month.

Oct. 23, 2020: Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden says he could meet Kim Jong Un if North Korea reduces the country’s nuclear capabilities.

Oct. 24, 2020: North Korea warns citizens to stay inside over fears that yellow dust from China could bring coronavirus.

Oct. 26, 2020: Biden says that North Korea possesses a great number of missiles because of Trump.

Oct 27, 2020: Moon’s special security adviser, Moon Chung-in, says signing a declaration to end the Korean War is the first step toward the denuclearization.

Oct. 28, 2020: US government issues a warning on a North Korean hacking group before the US presidential election.

Oct. 29, 2020: North Korea says South Korea is responsible for the death of a fisheries official killed at sea last month, although they reiterate regret over the killing.

Oct. 29, 2020: US Ambassador Harry Harris becomes honorary citizen of Seoul in recognition of his efforts to expand exchanges between the city and the United States.

Oct. 31, 2020: A UN panel says the al-Shabab Islamic extremist group used a North Korean mortar in a terrorist attack in Somalia earlier this year.

Nov. 1, 2020: North Korea imposes requirements on foreigners to fight against coronavirus.

Nov. 2, 2020: North Korea argues that the South is plotting to bring in additional U.S. missile defense system in the country, saying that it would lead to “self-destruction.”

Nov. 3, 2020: ROK troops take into custody a North Korean man who crossed the border.

Nov. 4, 2020: Unification Minister Lee In-young urges North Korea to restore cross-border communication lines between the two Koreas.

Nov. 6, 2020: South Korean national security chief Suh urges US government to resume talks with the North Korean regime.

Nov. 8, 2020: President Moon congratulates Joe Biden on his election victory.

Nov. 9, 2020: ROK Foreign Minister Kang Kyung-hwa visits Washington for talks with Pompeo.

Nov. 11, 2020: Foreign Minister Kang reaffirms efforts to continue ensuring peace on the Korean Peninsula after Biden’s election.

Nov. 12, 2020: Moon and Biden reaffirm commitment to their alliance and to work together closely on the North Korean nuclear issues in a phone call.

Nov. 13, 2020: Chairman of the Democratic Party of South Korea Lee Nak-yon calls on Biden to keep the deal signed between North Korean leader Kim and President Trump in 2018.

Nov. 15, 2020: Three members of ruling Democratic Party of South Korea leave for Washington for meetings with US congressional leaders and experts on the Korean Peninsula issues.

Nov. 16, 2020: Ambassador Harris congratulates four Korean-Americans on their election to the House of Representatives.

Nov. 17, 2020: US Army Chief of Staff Gen. James C. McConville meets South Korean Defense Minister Suh Wook to discuss ways to strengthen and expand cooperation.

Nov. 18, 2020: Unification Minister Lee says South Korea will formally offer talks with North Korea when the coronavirus wanes.

Nov. 19, 2020: Department of Treasury adds two North Korean enterprises that operate in Russia to sanctions list on North Korea for alleged involvement in the exportation of “forced labor.”

Nov. 20, 2020: North Korea accuses the UN Security Council for labeling the country’s space program as threats, calling the agency an “undemocratic organ devoid of impartiality.”

Nov. 20, 2020: International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) suspects North Korea of producing enriched uranium at the Kangson facility.

Nov. 22, 2020: South Korea agrees to boost cooperation with US Air Force to respond better to emerging space threats.

Nov. 23, 2020: Unification Minister Lee stresses that a breakthrough in South-North Korean ties could come “sooner than expected.”

Nov. 24, 2020: Kim Chong-in, leader of South Korea’s main opposition People Power Party (PPP), says South Korea may need to consider acquiring nuclear weapons if North Korea does not give up nuclear weapons.

Nov. 24, 2020: US State Department offers up to $3 million in funding for organizations working for North Korean human rights.

Nov. 26, 2020: China’s top diplomat Wang Yi and Kang hold talks in Seoul, discussing North Korea’s nuclear program and preparing a visit of Chinese President Xi Jinping.

Nov. 27, 2020: North Korean hackers are suspected of trying to break into the systems of British drug company AstraZeneca in recent weeks.

Nov. 27, 2020: Former Commander of US Forces Korea (USFK) Burwell Bell warns South Korea may lose allies if the country arms itself with nuclear weapons.

Nov. 29, 2020: North Korea reinforces border lockdown to prevent the COVID-19 pandemic from spreading into its country.

Nov. 30, 2020: US expert says North Korean leader Kim Jong Un and his family have been vaccinated for the coronavirus with a vaccine provided by China.

Dec. 1, 2020: Department of State accuses China of “flagrant violation” of its obligation to enforce international sanctions on North Korea, saying the US would offer rewards up to $5 million for information about sanctions evasions.

Dec. 2, 2020: North Korean hackers have attempted to hack at least six pharmaceutical companies developing COVID-19 vaccines in the US, the UK, and South Korea.

Dec. 3, 2020: Six US soldiers and two other civilians in South Korea test positive for coronavirus.

Dec. 4, 2020: ROK Minister of Unification Lee promises aid organization activists to send humanitarian assistance to North Korea.

Dec. 4, 2020: Head of US Army Pacific, Gen. Paul LaCamera, is nominated to be next commander of US Forces Korea (USFK).

Dec. 8, 2020: Biegun arrives in South Korea for talks with South Korean officials, including the foreign minister and the minister of unification, regarding bilateral alliance and stalled nuclear negotiations with North Korea.

Dec. 9, 2020: Treasury Department announces new sanctions on six entities and four vessels related to North Korea.

Dec. 10, 2020: Biegun calls on North Korea to return to dialogue for complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.

Dec. 11, 2020: Kim Yo Jong, sister of the North Korean leader, slams the ROK foreign minister for “reckless remarks” on Pyongyang’s coronavirus handling.

Dec. 12, 2020: Biegun reaffirms the US commitment to complete denuclearization of North Korea.

Dec. 15, 2020: North Korea starts regular winter-time drills, showing no signs of unusual movements.

Dec. 16, 2020: Trump says he will veto US defense bill, which includes limits on the president’s ability to withdraw troops from countries including South Korea.

Dec. 18, 2020: USFK Commander Gen. Robert Abrams calls for “immediate and aggressive” antivirus measures.

Dec. 19, 2020: United Nations Command (UNC) suspends tours to truce village of Panmunjom due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Dec. 20, 2020: North Korea says it will expand its Mount Kumgang tourist complex in “our way,” despite hopes of revived inter-Korean cooperation there.

Dec. 21, 2020: Presidential Secretary Noh Kyu-duk is named Seoul’s new top nuclear envoy.

Dec. 23, 2020: USFK will be the first group in South Korea to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. It will start administering the Moderna vaccine against coronavirus to frontline health workers and first responders.

Dec. 24, 2020: US State Department expresses strong support for South Korea to defend its air space after Chinese and Russian military aircrafts entered the KADIZ.

Dec. 25, 2020: Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccines for USFK arrive in South Korea.

Dec. 26, 2020: ROK Defense Ministry discusses with related authorities whether ROK Army troops assigned to USFK can get the COVID-19 vaccine shipped for US soldiers in South Korea.

Dec. 27, 2020: North Korea’s trade with China slumps to just $2,382 in November due to Pyongyang’s measures to stop the entry of the coronavirus into the country.

Dec. 29, 2020: US Air Force reconnaissance plane flies over Korea as North Korea appears to prepare a military parade.

Dec. 30, 2020: Data shows six countries—Russia, Switzerland, Sweden, Norway, Canada, and Bulgaria—have provided nearly $10 million in food aid this year to help North Korea respond to chronic food shortages.

Dec. 31, 2020: USFK-affiliated South Korean civilian workers and troops begin getting COVID-19 vaccinations. They are the country’s first citizens getting vaccinated against the virus.