Authors

Ji-Young Lee

Ji-Young Lee is a political scientist who teaches at American University’s School of International Service. She is the author of China’s Hegemony: Four Hundred Years of East Asian Domination (Columbia University Press, 2016). Her current work concerns historical Korea-China relations with a focus on military interventions, as well as the impact of China’s rise on the U.S. alliance system in East Asia. She has published articles in Security Studies, International Relations of the Asia-Pacific, and Journal of East Asian Studies. Previously, she was a Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Politics and East Asian Studies at Oberlin College, a POSCO Visiting Fellow at the East-West Center, a non-resident James Kelly Korean Studies Fellow with the Pacific Forum CSIS, an East Asia Institute Fellow, and a Korea Foundation-Mansfield Foundation scholar of the U.S.-Korea Scholar-Policymaker Nexus program. She received her Ph.D. and M.A. from Georgetown University, an M.A. from Seoul National University, and a B.A from Ewha Womans University in South Korea.

Articles by Ji-Young Lee

Japan - Korea

September — December 2023The Year 2023—Major Turning Point and Blossoming Cooperation

The year 2023 was a turning point for Japan-South Korea relations. There was a breakthrough in the issue of compensating forced laborers, which led South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol and Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio to meet seven times since their summit in March. Shuttle diplomacy has been fully resumed. By year’s end, their cooperation in new areas such as energy, critical and emerging technology, development and humanitarian assistance, space, and cyber is blossoming. Last year will be remembered as the year that began to demonstrate a real potential for Seoul and Tokyo to be like-minded global partners, along with Washington. If the first half of 2023 was a speed chase to get to the finish line—the Camp David trilateral summit meeting—the latter half of 2023 was a coordinated plan to prepare for many more races. As noted in our last issue of Comparative Connections, the Camp David trilateral summit represented a potential harbinger for the future of Japan-Korea relations.

Japan - Korea

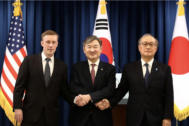

May — August 2023Camp David: Institutionalizing Cooperation Trilaterally

Japan-South Korea relations are going strong. In the months leading up to the historic Camp David trilateral summit in August, we saw the return of shuttle diplomacy between Korea and Japan. If President Yoon Suk Yeol’s March visit to Japan was groundbreaking, Prime Minister Kishida Fumio’s May visit to Seoul signified the continued momentum of improving bilateral ties. The Aug. 18 trilateral summit meeting, where President Biden, President Yoon, and Prime Minister Kishida announced bold steps to cement trilateral cooperation into the institutional fabric of the relationship, represents the deepest attempt in recent memory. A successful trilateral summit like this one was possible only because Seoul and Tokyo mended their bilateral ties. A positive cycle is expected the other way around, as well. For example, the “Commitment to Consult” —to expeditiously “share information, align messaging and coordinate response actions” among the three leaders—will likely create more incentives and opportunities for Seoul and Tokyo to keep bilateral relations friendly and cooperative.

Japan - Korea

January — April 2023The Return of Shuttle Diplomacy

In March 2023, Japan and South Korea had a long-awaited breakthrough in their bilateral relations, which many viewed as being at the lowest point since the 1965 normalization. On March 16, South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol and Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio held a summit in Tokyo and agreed to resume “shuttle diplomacy,” a crucial mechanism of bilateral cooperation that had been halted for about a decade. Behind the positive developments was President Yoon’s political decision on the issue of compensating wartime forced laborers. The two leaders took steps to bring ties back to the level that existed prior to actions in 2018 and 2019, which precipitated the downward spiral in their relationship. Japan decided to lift the export controls it placed on its neighbor following the South Korean Supreme Court ruling on forced labor in 2018. South Korea withdrew its complaint with the World Trade Organization on Japan’s export controls. Less than a week after the summit, Seoul officially fully restored the information sharing agreement (GSOMIA) that it had with Tokyo. They also resumed high-level bilateral foreign and security dialogues to discuss ways to navigate the changing international environment together as partners.

Japan - Korea

September — December 2022Japan and South Korea as Like-Minded Partners in the Indo-Pacific

The last four months of 2022 saw a flurry of bilateral diplomatic activities between Japan and South Korea in both nations’ capitals and around the world. They focused on 1) North Korea, 2) the issue of wartime forced labor, and 3) the future of Seoul-Tokyo cooperation in the Indo-Pacific region. Despite mutual mistrust and the low approval ratings of Prime Minister Kishida Fumio and President Yoon Suk Yeol, both leaders had the political will to see a breakthrough in bilateral relations. Another signal came in the form of new strategy documents in which Seoul and Tokyo explained their foreign and security policy directions and goals. On Dec. 16, the Kishida government published three national security-related documents—the National Security Strategy (NSS), the National Defense Strategy (NDS), and the Defense Buildup program. On Dec. 28, the Yoon government unveiled South Korea’s Strategy for a Free, Peaceful, Prosperous Indo-Pacific Region, its first-ever Indo-Pacific strategy. Although each document serves a somewhat different purpose, it is now possible to gauge how similarly or differently Japan and South Korea assess challenges in the international security environment, and how they plan to respond to them.

Japan - Korea

May — August 2022The Passing of Abe and Japan-Korea Relations

How might the passing of former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo impact Tokyo’s approach to Seoul? This unexpected turn of events loomed large in the minds of many who have been cautiously optimistic that Japan and South Korea would take steps toward a breakthrough in their stalled relations. In our last issue, we discussed how this summer could provide good timing for Seoul and Tokyo to create momentum in this direction after Yoon Suk Yeol’s inauguration as president in South Korea and the Upper House election in Japan. However, the results from this summer were mixed. Seoul and Tokyo have not yet announced whether Yoon and Kishida will hold a summit any time soon. Both leaders ended the summer juggling domestic politics amid declining approval ratings. However, there were some meaningful exchanges between the two governments, signaling that both sides were interested in improving relations.

Japan - Korea

January — April 2022South Korea’s New President and a Seoul-Tokyo Reset?

What impact will the victory of Yoon Seok-yul in South Korea’s presidential elections have on Seoul-Tokyo relations? During his campaign, Yoon repeatedly emphasized the “strategic importance of normalizing” and improving relations with Japan. It was an open secret that Yoon was Tokyo’s preferred candidate. With his May inauguration, opportunities for a diplomatic reset are on the horizon. Unsurprisingly, however, Japan is responding cautiously to overtures. Prime Minister Kishida Fumio sent his foreign minister to Yoon’s inauguration on May 10, instead of attending himself, especially as he looks to the Upper House election in July. Seoul and Tokyo will probably schedule a long-awaited summit meeting when they begin to move toward addressing the issue of wartime forced laborers. That issue has strained bilateral ties since the South Korean Supreme Court ruled in favor of Korean wartime forced laborers in separate decisions in late 2018, leading to drawn-out legal processes against the court orders. Yoon’s election win has not changed the Japanese position, which maintains that the reparations issue was fully settled by the 1965 normalization treaty.

ROUNDTABLE

February 23, 2022South Korea’s Presidential Election

Japan - Korea

September — December 2021Awaiting a Breakthrough? PM Kishida and South Korea’s Presidential Candidates

The year 2021 ended with no breakthroughs in Japan-Korea relations. Bilateral ties remain stalled over South Korea’s 2018 Supreme Court ruling on forced labor during Japan’s occupation of the Korean Peninsula and Japan’s export restrictions placed in 2019 on key materials used for South Korea’s electronics industry. The inauguration of Kishida Fumio as Japan’s new prime minister in September did not lead to a new momentum for addressing these bilateral issues, as both Tokyo and Seoul adhered to their positions. Prime Minister Kishida, while acknowledging that Japan’s relationship with South Korea should not be left as is, largely reiterated Tokyo’s official stance from the Abe and Suga governments that Seoul should first take steps on the forced labor issue. South Korean President Moon Jae-in sent a letter congratulating Kishida on his inauguration, signaling willingness to talk about bilateral challenges. Developments in the final months of 2021 are a reminder that there is no easy solution to these issues in sight.

Japan - Korea

May — August 2021Unrealized Olympic Diplomacy

In the summer months of 2021, the big question for many observers was whether Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide and President Moon Jae-in would hold their first summit meeting during the Tokyo Olympic Games. Cautious hope was in the air, especially on the South Korean side. However, by the time the Olympics opened in late July, any such hope was dashed amid a series of unhelpful spats. Seoul and Tokyo decided that they would not gain much—at least not what they wanted from the other—by holding a summit this summer. With Suga’s announcement of his resignation as head of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) at the end of September, barring any sudden turn of events, his tenure as Japanese prime minister will be recorded as one that did not have a summit with a South Korean president.

Japan - Korea

January — April 2021Difficult to Disentangle: History and Foreign Policy

Unsurprisingly, historical issues proved difficult to disentangle from other foreign policy issues in Japan-South Korea relations, which remained at the “worst level since the normalization” in the first four months of 2021. The Seoul Central District Court’s ruling on Jan. 8 that the Japanese government should pay damages to victims of sexual slavery during World War II set the tone for contentious relations at the beginning of the year. While the Moon Jae-in administration made gestures to mend ties, the Suga administration maintained that South Korea should take concrete measures to roll back the 2018 South Korean Supreme Court ruling on Japanese companies requiring them to compensate wartime forced laborers. Export restrictions levied by Japan against South Korean companies in 2019 remain in place, while the case is with the World Trade Organization after South Korea reopened a complaint in 2020 that was filed and then suspended in 2019.