Articles

For the past two years, US officials have made reference to a new Indo-Pacific Strategy. The June 1 release of the Defense Department’s Indo-Pacific Strategy Report provides some clarification and contains many familiar themes, including the need for a credible forward presence and strengthened alliances and partnerships “to preserve a free and open Indo-Pacific where sovereignty, independence, and territorial integrity are safeguarded.” The Report further notes “the critical linkages between economics, governance, and security.” Not to be outdone, ASEAN introduced its own Outlook on the Indo-Pacific, with “inclusivity” as the central theme. The G20 meeting in Osaka was probably as successful as was possible, but the group offered little more than rhetorical support for efforts to quell the US-China trade war. Finally, the Japan, South Korea, China trilateral provided some reason for hope –but just a little.

For the past two years, US defense officials have made reference to a new Indo-Pacific Strategy. We have tracked its emergence while arguing that there was more continuity than change in this administration’s approach to this “priority” region. For the most part, we were right, at least as far as its military dimension was concerned. The June 1 release of the Defense Department’s Indo-Pacific Strategy Report, subtitled “Preparedness, Partnerships, and Promoting a Networked Region,” contains many familiar themes, including the need for a credible combat-forward presence and strengthened alliances and partnerships “to preserve a free and open Indo-Pacific where sovereignty, independence, and territorial integrity are safeguarded.”

The Report further notes that “advancing this Indo-Pacific vision requires an integrated effort that recognizes the critical linkages between economics, governance, and security – all fundamental components that shape the region’s competitive landscape.” The security aspects were addressed by then-Acting Defense Secretary Mike Shanahan at this year’s Shangri-La Dialogue; rule of law and economic cooperation were central themes stressed by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo at the ASEAN Regional Forum and the US-ASEAN ministerial; and economic priorities (the major divergence from prior administrations) were clearly in evidence at the G20 meeting in Japan.

Not to be outdone, ASEAN introduced its own Outlook on the Indo-Pacific. If “free and open” was the buzzword of the US report, “inclusivity” was ASEAN’s central theme. Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzo hosted a G20 meeting that was probably as successful as was possible given seeming US hostility to economic multilateralism, but the group offered little more than rhetorical support for efforts to quell the US-China trade war. Finally, the Japan, South Korea, China trilateral provided some reason for hope – but just a little.

Preparedness, partnerships, and promoting a networked region

Those who have been following our commentaries on the emerging strategy will find few surprises in the DoD Indo-Pacific Strategy Report. As expected, it stresses both the importance of US alliances and partnerships and the need for these allies and partners to do more. It also minces no words in describing the primary challenges: the PRC as a “revisionist power,” Russia as a “revitalized malign actor,” and North Korea as a “rogue state.” Somewhat surprising – and disconcerting – was Acting Secretary Shanahan’s accusation, in his opening message, that the People’s Republic of China (PRC), “under the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party [emphasis added], seeks to reorder the region to its advantage by leveraging military modernization, influence operations, and predatory economics to coerce other nations.” Previous administration complaints had focused on China’s behavior, this one seemed to aim at its ideology as well, leading to Chinese counter-accusations that Washington is really seeking fundamental changes in China’s political system.

Nonetheless, the word “enemy” appears nowhere in the China section of the Report, and it further reminds the reader that “one of the most far-reaching objectives of the National Defense Strategy is to set the military relationship between the United States and China on a long-term path of transparency and non-aggression.” To this end, it further notes that “pursuit of a constructive, results-oriented relationship between our two countries is an important part of US strategy in the Indo-Pacific.”

Preparedness. The focus here, as expected, is on “peace through strength,” “effective deterrence,” and “combat-credible . . . forward-postured” forces. This section also stresses the need to “prioritize investments that ensure lethality against high-end adversaries.”

Partnerships. While President Trump’s tweets have raised anxiety levels among traditional US allies, the Report reaffirms the official view that “our unique network of allies and partners is a force multiplier” while reinforcing the Defense Department’s “commitment to established alliances and partnerships,” even while seeking new ones with countries who “share our respect for sovereignty, fair and reciprocal trade, and the rule of law.”

Networking. Countering the argument that “America first” means “America alone,” the Indo-Pacific Strategy calls for “strengthening and evolving US alliances and partnerships into a networked security architecture to uphold the international rules-based order,” while also continuing “to cultivate intra-Asian security relationships capable of deterring aggression, maintaining stability, and ensuring free access to common domains.” Specific references are made to trilateral cooperation (US-ROK-Japan, US-Japan-Australia, and US-India-Japan) and to the various ASEAN-led multilateral forums (while tipping its hat to “ASEAN centrality”). The DoD also “supports the recent re-establishment of the diplomatic quadrilateral consultations – or Quad – between the United States, Australia, India, and Japan.” Note the emphasis on the Quad as a “diplomatic” vice security mechanism.

Shanahan in Singapore

It was no accident that the Indo-Pacific Strategy Report was released the day prior to Acting Secretary Shanahan’s debut at this year’s Shangri-La annual gathering. In his prepared remarks, he made all the above points, while also stressing the administration’s commitment to enduring principles of international cooperation: respect for sovereignty and independence of all nations, large and small; peaceful resolution of disputes; free, fair, and reciprocal trade and investment, which includes protections for intellectual property; and adherence to international rules and norms, including freedom of navigation and overflight – further noting that “these are not American principles; they are broadly accepted across this region and the world.”

Acting U.S. Defense Secretary Patrick Shanahan speaks at the IISS Shangri-la Dialogue in Singapore, June 1, 2019. REUTERS/Feline Lim

Taking a page from the Chinese playbook, Shanahan did not criticize China by name in his prepared remarks, instead noting that “some seem to want a future where power determines place and debt determines destiny,” that “some in our region are choosing to act contrary to the principles and norms that have benefitted us all,” and that the greatest threat comes from “actors who seek to undermine, rather than uphold, the rules-based international order.” He did however talk about the need and desire for US-China cooperation, stressing that “China could still have a cooperative relationship with the United States,” and that “it is in China’s interests to do so.”

Esper doubles down and adds a dimension

Those who might be concerned that the change in DoD leadership – Secretary of the Army Mark Esper replaced Shanahan as acting defense secretary in early July and was officially confirmed as the 27th US secretary of Defense on July 23 – might impact the new Strategy can rest easy. Esper’s first trip as defense secretary was to the Indo-Pacific region – Australia, New Zealand, Japan, South Korea, and Mongolia – where he reaffirmed his and Washington’s commitment to a free and open Indo-Pacific: “I want to go out to the theater, visit with some of our longest standing allies, and new partners, and to affirm our commitment to the region to reassure our allies and our partners, and to make sure they understand that it’s not just the department’s commitment, but my personal commitment and the United States’ commitment to this region.”

Speaking to students at the Naval War College in late August, he went even further, stating “we must be present in the region. Not everywhere, but in the key locations. This means looking at how we expand our basing locations, investing more time and resources in certain regions we haven’t been to in the past.” Just where those new locations will be is open to speculation. Esper also repeated the favorite mantra of his several most recent predecessors: “we have to continue to fly, to sail and to operate wherever international rules allow to preserve freedom of navigation for both military and commercial operations.”

Pompeo at the ARF/ASEAN Ministerial

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo also made a high-profile visit to the region during this reporting period to participate in the annual ASEAN Regional Forum and US-ASEAN Ministerial, along with a number of bilateral and broader meetings. A constant theme was adherence to the rule of law. As he stated during brief opening remarks at the US-ASEAN Ministerial, “American diplomacy with ASEAN has been consistently guided by our desire for a partnership of respect towards the sovereignty of each of our nations, and a shared commitment to the fundamental rules of law, human rights, and sustainable economic growth.” But he further stressed that “we don’t ever ask any Indo-Pacific nation to choose between countries. Our engagement in this region has not been and will not be a zero-sum exercise. Our interests simply naturally converge with yours to our mutual benefit.”

Secretary Pompeo poses with the Foreign Ministers of Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia and Laos during the US-ASEAN Ministerial Meeting on the sidelines of the ASEAN Foreign Ministers Meeting. Photo: US Department of State

Speaking to the Siam Society in Bangkok the next day, he returned to the same themes: “We want a free and open Indo-Pacific that’s marked by the core tenants of the rule of law, of openness, of transparency, of good governance, of respect for sovereignty of each and every nation, true partnerships.” Washington’s respect for sovereignty was mentioned no less than seven times in his remarks and Q&A session.

While one would think this term would resonate with ASEAN, it appeared nowhere in the ARF Chairman’s Statement; nor did openness or good governance. Transparency was mentioned once (in praising the ARF’s unspecified efforts to promote it) as was, ironically, the rule of law (in supporting Myanmar’s efforts to bring peace, harmony, and the rule of law in Rakhine State).

As an aside, the Thai Chairman’s Statement “noted with satisfaction that the number of ARF activities on preventive diplomacy continued to increase, while confidence-building measures continued to be strengthened.” For an alternative view on the ARF’s progress (or lack thereof) toward preventive diplomacy, we call your attention to the following PacNet and more extensive Issues & Insights report on The ASEAN Regional Forum at 25: Moving Forward or Standing Still?

ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific

After stressing the Trump administration’s support for ASEAN centrality at the US-ASEAN Ministerial, Secretary Pompeo also noted that he was “heartened to see ASEAN recently released its outlook on the Indo-Pacific, which also supports sovereignty, transparency, good governance, a rules-based order, among many other things.”

This is true – to a point. The ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific, issued on June 23 in advance of the ARF, states that it is “based on the principles of strengthening ASEAN Centrality, openness, transparency, inclusivity, a rules-based framework, good governance, respect for sovereignty, non-intervention, complementarity with existing cooperation frameworks, equality, mutual respect, mutual trust, mutual benefit and respect for international law.”

Pompeo had every reason to be heartened and was wise to stress the complementarity of the two approaches. Others have chosen to stress the differences instead. Long-time ASEAN watcher Amitav Acharya argues that the differences are captured in the terminology used by the two countries: “the United States wants a ‘free’ and ‘open’ Indo-Pacific, echoing the wording used by Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, but with a more overt military–strategic orientation. In comparison, Indonesia [which he cites as the primary author of the document] seeks an ‘open’ and ‘inclusive’ Indo-Pacific. The United States does not use ‘inclusive’ while Indonesia does not use ‘free’.” To Acharya, free denotes “domestic political openness and good governance as key ingredients, putting it at odds with China” while inclusivity “implies that its policy is not meant to isolate China.” Regardless of your interpretation of the ASEAN document – and we see more similarities than fundamental differences – both the US and ASEAN concepts agree on one central point: ASEAN centrality lies at its heart.

Abe’s G20 ends with a whimper, not a bang

Japanese Prime Minister Abe hosted the other big multilateral get-together of this reporting period, the annual G20 Summit. Abe had hoped the Osaka meeting would address pressing global issues and reinvigorate multilateral diplomacy. He, like all other world leaders who harbor similar ambitions – are you listening, Emmanuel Macron? – was frustrated and was forced to settle for a lengthy declaration that was marked by platitudes and vague statements.

The statement noted that “Global growth appears to be stabilizing and is generally projected to pick up moderately” but warned that “risks remain tilted to the downside.” The leaders pledged to promote “free, fair and non-discriminatory” trade and to “keep our markets open.” Pressure from Washington scratched any mention of protectionism, which would have prompted scrutiny and criticism of unilateral US tariffs. The group also provided “support for the necessary reform of the World Trade Organization”; failure to identify what constitutes “necessary” is diplomacy at its best or worst, depending on your point of view.

Abe should take pride in the statement’s endorsement of “quality infrastructure,” a Japanese concept that is intended to be a counterpoint to Chinese aid diplomacy and its risk of putting recipients in a “debt trap.” The G20 statement built on the G20 finance ministers’ communique, issued June 9, which highlighted the importance of “quality infrastructure” and endorsed the “G20 Principles for Quality Infrastructure Investment as our common strategic direction and high aspiration.” They also emphasized the need to improve debt transparency and secure debt sustainability.

The leaders statement also mentioned climate change. The leaders “recognize the urgent need for addressing complex and pressing global issues and challenges, including climate change…” and “stress the importance of accelerating the virtuous cycle and leading transformations to a resilient, inclusive, and sustainable future. We emphasize the importance of taking concrete and practical actions and collecting international best practices and wisdom from around the world, mobilizing public and private finance, technology and investment and improving business environments.” Another entire paragraph is devoted to ways to proceed. It concludes, however, with a third paragraph that is a paean to US policy and Washington’s decision to go its own way. It is a remarkable concession to the US and an indication of how much of an outlier Trump’s climate policies are.

As always, much of the substantive work at the G20 occurred during bilateral meetings on the sidelines. The most important of those (for our purposes) was the dinner between US President Donald Trump and Chinese Chairman Xi Jinping, at which they declared a truce in their escalating trade war. Trump agreed to halt the imposition of additional tariffs, and the two sides agreed to continue negotiations on a final deal. Trump also said that China had agreed to purchase more agricultural products, a point disputed by the Chinese. (For more, see the chapter on US-China relations in Comparative Connections.)

President Trump and President Xi at the G20 Summit in Osaka on June 29, 2019. Photo: Getty Images

Another notable development during the meeting was Trump’s tweeted invitation to North Korean leader Kim Jong Un to join him in the Joint Security Area at Panmunjom, when the US president visited South Korea after the Osaka summit. Kim obliged. (For more see the chapter on US-Korea relations in this issue of Comparative Connections.)

Ripples and tidal waves

The outcome of the Trump-Xi dinner had implications for all the leaders gathered in Osaka (and many who weren’t present as well). Assessments of the global economy increasingly identified the US-China trade dispute as the chief danger. In her remarks to the G20 finance ministers, Christine Lagarde, managing director of the International Monetary Fund, warned that “The principal threat stems from continuing trade tensions,” noting that the IMF estimated that the trade war could reduce global GDP by 0.5% in 2020, or about $455 billion. In July, IMF economists lowered their estimate of global growth by 0.1 percentage points to 3.2%.

Analysts have warned of the risks to smaller regional economies – “innocent bystanders” in one formulation – that could be upended by the trade spat. Already, the “Asia tiger” economies – Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, and South Korea – are feeling the impact. Japan, too, is affected, as its exports to China have tumbled, falling 8.2% in the first half of 2019, a decrease that well outpaced the deceleration of the Chinese economy (which still managed to post 6.25% growth from April to June).

Not all the regional economies are suffering, however. Australia’s nominal exports to China have increased by 30% since early 2018, the time that US tariffs were first imposed. In addition, uncertainty has prompted investors to buy gold, another one of the country’s big exports. Vietnam is another beneficiary, with its economy picking up speed as international businesses look for other places to invest as Trump focuses on China. The Vietnamese economy is projected to grow between 6.6-6.8% in 2019; a good part of the boost is a result of the US trade war with China. US imports from the country were up 36%. This is a mixed blessing: President Trump has since denounced Vietnam as “almost the single worst abuser of everybody.”

Might the “plus Three” matter?

One other multilateral meeting of note occurred this reporting period: the ASEAN Plus Three Foreign Ministers Meeting, which was held in Bangkok, Thailand on Aug. 2. Its statement was the usual mix of diplomatic boilerplate reiterating the importance of ASEAN centrality, concern about trade and economic prospects, calls for more cooperation on nontraditional security threats, and the general desire to promote and pursue greater Asian connectivity and integration. It also “urged all concerned parties to resume and continue peaceful dialogue and work together towards progress in the realisation of lasting peace, security, and stability in a denuclearised Korean Peninsula…”

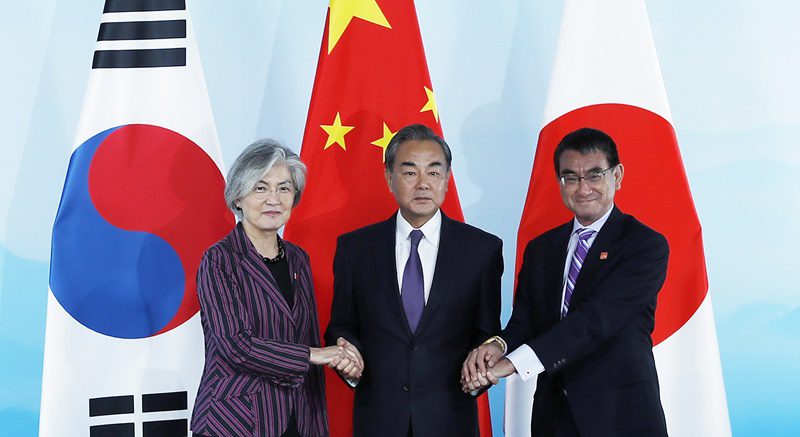

The “plus Three” component – Japan, South Korea and China – has always been an interesting if not undervalued element of the ASEAN process. On Aug. 21, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi hosted his counterparts, Kono Taro from Japan and Kang Kyung-wha from South Korea, for a trilateral discussion in Beijing. The meeting was preceded by commentary by Chen Youjun, a senior research fellow and director of regional economics office with the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies, who argued that China should assume its traditional regional role and help Seoul and Tokyo overcome their differences. “China has always played an active role in regional economic integration, which is why China could act as a mediator to help Japan and South Korea reach a compromise.” He went on to note that “easing their tense relationship under a trilateral FTA framework could be a way to avoid nationalist pressure inside the two countries.”

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi hosts his counterparts, Kono Taro from Japan and Kang Kyung-wha from South Korea, for a trilateral discussion in Beijing. Photo: Yonhap News

After the meeting, Wang Yi was not as forward leaning, merely noting at a press conference with Kono and Kang that “I would like Japan and South Korea to find a way to solve the issue.” Kono was also reserved, adding that the three countries should “strengthen cooperation,” since their economies combined account for 20% of the global GDP. “East Asia has a responsibility for global stability and prosperity,” he said.

At the end of August, culture and tourism ministers from the three countries met in Incheon and agreed to enhance cultural, sports, and people-to-people exchanges despite the mounting tensions over trade and history. The mood was cordial, in contrast to meetings between trade and foreign policy officials, and cultural cooperation seems to have survived the bilateral feuds. Given signs that tourism among the three is tapering off – blame history and faltering economies – that happy state of affairs may not persist. Indeed, there is little reason for optimism regarding any of the issues we identified in this period’s report. Uncertainty is likely to intensify as headwinds – political and economic – pick up strength.

May 2-8, 2019: Six naval vessels from the US, Japan, the Philippines, and India conduct a military exercise in the South China Sea including “formation exercises, communication drills, passenger transfers” and a leadership exchange on board the JS Izumo helicopter destroyer.

May 2-4, 2019: Japanese Defense Minister Iwaya Takeshi visits Vietnam and meets Defense Minister Ngo Xuan Lich and Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc in Hanoi. They agree to strengthen defense cooperation and sign an MOU to promote defense industry exchanges.

May 6, 2019: China protests the passage of the USS Preble and USS Chung-Hoon near the Spratly Islands the same day, claiming the ships traveled within 12 nm of its territory without permission. Officials also denounce the Pentagon’s 2019 report on China’s military power, saying it aims to “distort our strategic intentions and paint China as a threat.”

May 7-10, 2019: US Special Representative for North Korea Stephen Biegun visits Tokyo and Seoul to meet South Korean and Japanese officials.

May 8-10, 2019: Chinese Vice Premier Liu He meets US Special Representative Robert Lighthizer and Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin for the 11th round of trade talks in Washington DC. The talks conclude without a formal agreement and the Trump administration increases tariffs on $200 billion of Chinese imports from 10 to 25%.

May 8, 2019: China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs issues “stern representations” against the US in response to the unanimous passing of a non-binding resolution reaffirming support for Taiwan and the Taiwan Assurance Act of 2019 in the House of Representatives.

May 9, 2019: North Korea test-launches two short-range ballistic missiles that land in the East Sea. They are the first ballistic weapons the country has tested since November 2017.

May 9, 2019: US seizes the Wise Honest, North Korea’s second largest cargo ship, which is accused of violating international sanctions by transporting coal and heavy machinery to North Korea.

May 9, 2019: The 11th round of US, Japan, South Korea Defense Trilateral Talks (DTT) is held in Seoul to discuss regional security issues.

May 13, 2019: China announces that it will raise tariffs on $60 billion of US goods currently taxed between 5 and 10% up to 25% beginning on June 1. This includes commodities like “animal products, frozen fruits and vegetables,” as well as “baking condiments, chemicals and vodka.”

May 14, 2019: US Coast Guard cutter Bertholf practices search-and-rescue exercises with Philippines Coast Guard vessels BRP Batangas and BRP Kalanggaman near Scarborough Shoal.

May 16, 2019: USS William P. Lawrence participates in naval exercise La Perouse with five other vessels from France, Japan, and Australia in the Bay of Bengal. The exercise includes “sailing in formation, live-fire drills, communications, search and rescue, damage control and personnel transfers.”

May 18, 2019: USS William P. Lawrence joins JS Izumo and JS Marusame for a “cooperative naval deployment” in the Malacca Strait to improve communication and interoperability between the US Navy and Japan’s Maritime Self-Defense Force (MSDF).

May 20, 2019: USS Preble conducts a freedom of navigation operation (FONOP) near Scarborough Shoal in the South China Sea “to challenge excessive maritime claims and preserve access to the waterways as governed by international law.”

May 22, 2019: USS Preble and USNS Walter S. Diehl transit the Taiwan Strait to demonstrate “the U.S. commitment to a free and open Indo-Pacific.” China issues “stern representations” against the US in reaction.

May 23-28, 2019: Navies from the US, Japan, South Korea, and Australia launch the inaugural Pacific Vanguard exercise off Guam “to conduct cooperative maritime training.” Over 3,000 sailors take part in drills including “combined maneuvers, live fire exercises, defense counter-air operations, anti-submarine warfare, and replenishment at sea.”

May 27, 2019: Taiwan confirms that its National Security Council Secretary General David Lee met US national security adviser John Bolton during Lee’s May 13-21 visit to the US. It’s the first exchange between top security officials of both governments since 1979.

May 28-June 4, 2019: Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte visits Tokyo to deliver a keynote address at the 25th International Conference on The Future of Asia. Duterte also meets Prime Minster Abe to discuss “trade, investment and growing Chinese activity in disputed regional seas.”

May 29, 2019: Amnesty International releases report that chronicles seven unlawful attacks by the Tatmadaw against civilians in Rakhine state since the Jan. 4 attacks by the Arakan Army (AA) on police.

May 30, 2019: Narendra Modi is sworn in for a second term as India’s prime minister following a general election in which his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) won 303 of 542 parliamentary seats.

May 31-June 2, 2019: US Acting Secretary of Defense Patrick Shanahan presents the Indo-Pacific Strategy Report at Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore and identifies the region as the “priority theater” for the US.

June 2, 2019: China’s Defense Minister Wei Fenghe defends the use of force against protesters in Tiananmen Square in 1989 and its “vocational training centres” in Xinjiang as integral to ensuring that Chinese citizens “enjoy secure and stable lives” in his speech at the Shangri-La Dialogue.

June 2, 2019: China releases a white paper on economic and trade talks with the US, refuting the efficacy of the US tariffs and blaming the dissolution of the negotiation process on it.

June 3, 2019: Acting Secretary of Defense Shanahan and South Korean Minister of National Defense Jeong Kyeong Doo formally terminate the Freedom Guardian joint military exercises that were first suspended last year to reduce military tensions on the Korean Peninsula.

June 5, 2019: Thailand’s Parliament elects PM Prayut Chan-o-cha to remain in office.

June 5-7, 2019: Chinese Chairman Xi Jinping visits Russia to attend the 23rd St. Petersburg International Economic Forum. The two sides agree to upgrade bilateral ties to a “comprehensive strategic partnership,” sign more than $20 billion of deals in technology and energy to boost economic ties, and present themselves as champions of free trade and globalization.

June 9-10, 2019: Chinese vessel sinks a Filipino fishing boat near Reed Bank and leaves the 22 Filipino crewmen stranded until they are rescued by a Vietnamese fishing boat.

June 10, 2019: US Coast Guard (USCG) announces the deployment of cutters Bertholf and Stratton with the Navy’s Seventh Fleet in Yokosuka on the rationale that they will aid “law enforcement and capacity-building in the fisheries enforcement realm” in the Western Pacific.

June 12, 2019: US submits report to the UN Security Council’s North Korea Sanctions Committee blaming North Korea for breaching a UN-imposed cap on fuel imports through illicit ship-to-ship transfers.

June 13, 2019: US Senate confirms David Stilwell to be the assistant secretary of state for East Asia and the Pacific. The position had been vacant since 2017.

June 16-28, 2019: Protesters demand Chief Executive Carrie Lam’s resignation. Lam apologizes for “deficiencies in the Government’s work” regarding the extradition bill that spurred the largest protests in Hong Kong since 1997.

June 17, 2019: President Rodrigo Duterte calls the sinking of a Philippine fishing boat by a Chinese vessel “just a collision,” warning against military action toward China.

June 19, 2019: South Korea’s Special Representative for Korean Peninsula Peace and Security Affairs Lee Do-hoon meets US Special Representative for North Korea Stephen Biegun in Washington DC to discuss ways to facilitate the resumption of US-North Korea dialogue.

June 19, 2019: US Department of Treasury blacklists Russian Financial Society for allegedly aiding North Korea in sanctions evasion.

June 20, 2019: Japan’s Ministry of Defense and South Korea’s Air Force each cite two Russian military aircraft violating their air defense identification zones (ADIZ).

June 20-21, 2019: Chairman Xi travels to Pyongyang to meet Chairman Kim Jong Un. Xi promises to play a “positive and constructive role” in denuclearization and urges the continuation of US-DPRK talks, while Kim states that North Korea will “remain patient” despite “parties that have failed to respond positively” to negotiations.

June 20-23, 2019: Southeast Asian leaders meet in Bangkok for the 34th ASEAN summit. They adopt a joint declaration to combat plastic pollution in oceans and release statements regarding regional economic and security collaboration, the de-escalation of tensions in the South China Sea, and investigations into human rights violations in Myanmar.

June 21, 2019: US State Department condemns China’s “intense persecution” of religious faiths, particularly in Xinjiang, in its 2018 Annual Report on International Religious Freedom.

June 24, 2019: US, Japan, and Australia announce jointly financed $1 billion LNG project in Papua New Guinea.

June 27, 2019: Prime Minister Abe and Chairman Xi Jinping meet ahead of the G20 summit and agree to collaborate on “free, fair trade,” elevate their countries’ relationship “to the next level,” and confirm Xi’s state visit to Japan next spring. President Moon Jae-in also meets Xi to discuss denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula, Xi’s recent visit to Pyongyang, and bilateral cooperation. President Trump and Xi agree to a tentative truce ahead of negotiations during the G20 Summit.

June 28-29, 2019: The 14th meeting of the G20 convenes in Osaka, where leaders discuss trade tensions, WTO reforms, information security, climate change and migration.

June 29-30, 2019: President Trump visits South Korea. He and President Moon “reaffirm” the US-ROK alliance, describing it as “the linchpin of peace and security in the Indo-Pacific.” Trump shakes hands with North Korean Chairman Kim Jong Un at the Demilitarized Zone and agrees to continue negotiations with North Korea.

July 3, 2019: JS Izumo returns to Japan following a two-month extended naval deployment in the Indo-Pacific that included joint cooperation exercises with the US and other allies.

July 4, 2019: China’s Defense Ministry denies launching anti-ship missiles during recent exercise in the South China Sea, claiming drills “involved the firing of live ammunition.” Vietnam’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson responds to China’s exercises by referencing the UN Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), and that any activities should serve “regional peace, security, stability and cooperation.”

July 8, 2019: US Department of State approves $2.2 billion arms sale to Taiwan including 108 Abrams tanks and 250 Stinger missiles. China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs calls on the US to “immediately cancel” the sale and cease undermining “China’s sovereignty and security interests.”

July 10-21, 2019: Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs Stilwell makes his first official trip to Asia. He stops first in Japan before continuing to the Philippines where he leads the US delegation in the Bilateral Strategic Dialogue. He stops in South Korea on July 17 and concludes his tour in Thailand.

July 11-22, 2019: Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen tours the US and Caribbean on her “Journey of Freedom, Democracy and Sustainability.” Tsai stops in New York City for two nights on her way to visit Caribbean allies Haiti, St. Christopher and Nevis, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and St. Lucia. She stops in Denver on her way back to Taiwan.

July 19, 2019: Vietnam’s Foreign Ministry accuses Chinese oil survey vessel, Haiyang Dizhi 8, of having undertaken activities that “violated Vietnam’s exclusive economic zone and continental shelf,” in the South China Sea.

July 20, 2019: US Department of State calls on China to “cease its bullying behavior” in coercing ASEAN members from pursuing oil and gas activities in the South China Sea.

July 21, 2019: China’s State Council Information Office publishes a white paper to justify its treatment of Uighurs in Xinjiang, positing that they became Muslim by force of “religious wars and the ruling class.”

July 23, 2019: US Department of Justice indicts Dandong Industrial Development Co., its owner Ma Xiaohong, and three managers on charges of conspiracy to evade US sanctions in engaging with North Korean companies developing nuclear weapons.

July 23, 2019: Russia and China fly a joint patrol over the East China Sea. South Korea fires warning shots at two Russian Tu-95 strategic bombers, two Chinese H-6 bombers, a Russia A-50 early warning plane, and a Chinese KJ-2000 after they enter the Korean Air Defense Identification Zone. Japan lodges official complaints against Russia and China for violating its airspace.

July 24, 2019: China’s State Council Information Office releases the 10th defense white paper, China’s National Defense in the New Era.

July 24, 2019: USS Antietam conducts “a routine Taiwan Strait transit” to demonstrate “the US commitment to a free and open Indo-Pacific.”

July 25, 2019: North Korea test-fires two short-range ballistic missiles into the East Sea.

July 29, 2019: Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen commits $40 million to weapons purchases from China “to strengthen the army.”

July 31, 2019: North Korea test-fires two short-range ballistic missiles into the East Sea.

July 31, 2019: Philippines Foreign Affairs Secretary Teodoro Locsin files a diplomatic protest against China after over 100 Chinese fishing vessels were recorded around Philippines’ claimed Pag-asa (Thitu) Island.

Aug. 2-9, 2019: US Defense Secretary Esper makes his first official trip to Asia with stops in Australia, New Zealand, Japan, Mongolia, and South Korea.

Aug. 2, 2019: Japan’s Foreign Ministry calls Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev’s visit to Iturup island in the South Kurils “extremely regrettable.”

Aug. 2, 2019: US formally withdraws from the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces Treaty.

Aug. 2, 2019: Japan’s Cabinet votes to remove South Korea from its export “white list.” President Moon threatens countermeasures, including reconsidering renewal of its military information-sharing deal with Japan.

Aug. 2, 2019: The 20th ASEAN Plus Three Foreign Ministers Meeting is held in Bangkok.

Aug. 2, 2019: The 26th ASEAN Regional Forum is held in Bangkok.

Aug. 2, 2019: South Korea’s military detects two short-range missiles fired from North Korea’s East Coast into the East Sea.

Aug. 4, 2019: Secretary of State Pompeo and Defense Secretary Esper meet Australian Foreign Affairs Minister Marise Payne and Defense Minister Linda Reynolds in Sydney for the 29th Australia-United States Ministerial Consultations “to deepen economic, security, and strategic cooperation in the Indo-Pacific region and globally.”

Aug. 5-20, 2019: US and South Korea hold joint-military exercises Dong Maeng 19-2, a “scaled-back combined command post exercise” that is executed primarily through computer simulations.

Aug. 5, 2019: India’s Home Minister announces the decision to abolish Article 370 of the constitution, removing Kashmir’s special status.

Aug. 5, 2019: US Treasury Department formally accuses China of “manipulating its currency.”

Aug. 5, 2019: Secretary of State Pompeo visits Pohnpei, the first official visit by a sitting secretary of State to the Federated States of Micronesia.

Aug. 6, 2019: South Korea’s military reports that two “short-range ballistic missiles” were launched by North Korea into the Sea of Japan.

Aug. 7, 2019: UN sanctions committee on North Korea releases a report showing DPRK-directed cyberattacks have raised to date $2 billion in funds to support its WMD programs.

Aug. 10, 2019: North Korea launches “the fifth round of launches by Pyongyang in just over two week,” sending two short-range ballistic missiles into the Sea of Japan.

Aug. 12, 2019: South Korea downgrades Japan from “most trusted status” to a newly established category, citing Tokyo’s violations of “the basic principles of the international export control regime.”

Aug. 13-16, 2019: Leaders of the 18 member countries convene in Tuvalu for the 50th meeting of the Pacific Islands Forum and issue the Kainaki II Declaration for Urgent Climate Change Action Now immediately following the session.

Aug. 16, 2019: North Korea test-fires two short-range ballistic missiles into the Sea of Japan, “the sixth launch of projectiles by the country since July 25.”

Aug. 20, 2019: US State Department approves $8 billion arms sale comprising 66 F-16 fighter jets to Taiwan.

Aug. 23, 2019: South Korea notifies Japan that it will withdraw from the General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA).

Aug. 24, 2019: North Korea launches its seventh projectile test since July 25. Korean Central News Agency reports the successful test of a “super-large multiple rocket launcher.”

Aug. 26, 2019: Indonesian President Joko Widodo announces that Indonesia will relocate its capital from Jakarta to East Kalimantan on the island of Borneo.

Aug. 28, 2019: USS Wayne E. Meyer sails near Fiery Cross and Mischief Reef “to challenge excessive maritime claims and preserve access to the waterways governed by international law.”

Aug. 29, 2019: In a meeting with China’s Chairman Xi in Beijing, Philippine President Duterte raises the 2016 ruling on China’s 9-dash line in the South China Sea. Xi reiterates “China’s refusal to recognize the arbitral ruling.”

Aug. 30, 2019: Culture and tourism ministers of South Korea, Japan and China meet in Incheon and agree to increase cultural, sports and people-to-people exchanges despite tensions over trade and their shared history.