Current Issue

Regional Overview

May — November 2024Regional Overview: The Year of Elections (Finally) Ends

The “year of elections” culminated in the allegedly (but not actually) “too close to call” US presidential elections on Nov. 5, which resulted in Donald Trump’s scheduled return to the oval office on Jan. 20, 2025. Trump has wasted no time identifying his preferences for key leadership positions in his incoming administration, some surprising, some shocking, and a few somewhat disturbing (to us, at least), although most of his national security/foreign policy choices appear more mainstream. While we would not be bold (or foolish) enough to make firm predictions regarding future policy, we will speculate on expected trends and characteristics, while acknowledging at the onset that Trump prides himself on being unpredictable (and has largely succeeded in this quest).

While elections elsewhere have gone largely as expected, two unexpected domestic political developments promise to impact US policy and regional stability; namely, the failed attempt by Republic of Korea President Yoon Suk Yeol to declare martial law which resulted in his impeachment, and the political turmoil in Japan that has left the Liberal Democratic Party for the first time in decades finding itself at the helm of a minority government. Elsewhere (and largely overlooked), the usual spate of multilateral meetings took place in the second half of the year—the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Leaders’ Meeting, the G20 gathering, the East Asia Summit and companion ministerial-level ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), the BRICS Summit, etc. —amid enhanced military activity and enhanced trilateral/minilateral cooperation.

Temp Placement of Figure 1 G20 Leaders Meeting

Trump Triumphs

Figure 1 PM Modi made the remarks at the G20 session on “Social Inclusion and the Fight Against Hunger and Poverty.” (Photo: X/@narendramodi)

There should be no repeat of the Jan. 6, 2020 mayhem as Vice President Kamala Harris graciously accepted defeat and congratulated president-elect Donald Trump on his Nov. 6 victory. Trump was quick in identifying his planned nominees for key national security posts, including Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida to be secretary of state and Florida Republican Rep. Michael Waltz as National Security Advisor. Rubio is expected to sail through the Senate confirmation process and National Security Council members are not subject to ratification. This holds true as well for Trump’s choice of former State Department official Alex Wong to serve as deputy national security adviser. Wong served as deputy special representative for North Korea during the first Trump administration and was closely involved in arranging Trump’s summits with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un.

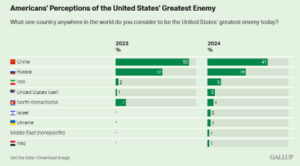

One thing Rubio and Waltz and other national security-related potential nominees, like U.S. ambassador to the United Nations nominee Congresswoman Elise Stefanik (R-NY) and CIA Director-designate (and former Director of National Intelligence) John Ratcliffe have in common is strong anti-China and anti-authoritarian views. Prospective Secretary of Defense (and former Fox News host) Pete Hegseth would join this chorus if his nomination is approved (which seemed somewhat likely but is by no means assured at this writing).

The real wild card on the national security team is former Hawaii Democratic Rep. Tulsi Gabbard who Trump has chosen to serve as his director of national intelligence, a job for which (in our not-so-humble opinions) she is uniquely unqualified. At this writing she appears to be the candidate most likely to be rejected by the Senate.

On the economic front, Trump has identified hedge fund CEO Scott Bessent to be Treasury secretary and billionaire Harold Lutnick as Commerce secretary. Both are strong proponents of tariffs; Lutnick, among other duties, oversees the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative.

Still to come will be the under-secretaries and assistant secretaries for the various Asia-related posts who will be presenting their bosses with policy alternatives and assessments. They in turn will be guided by the new administration’s key strategy documents such as the White House-produced National Security Strategy and the Pentagon’s National Defense Strategy.

What we think we know . . .

. . . based on what he’s done before.

Unlike most who have come before or since, Trump is more transactional, more unpredictable (which he sees as a virtue and many others see as a vice), more confrontational (with friends and potential foes alike), and more mercurial. When it comes to the promotion of democracy and values-based policies, however, he is much less ideological (some would say less sanctimonious) than many of his predecessors. His foreign policy approach is more trade-based (or more accurately deficit-based), than security-oriented. He is more unilateralist than multilateralist and places less value in alliances and like-minded security relationships than both Democratic and Republican predecessors.

His focus is primarily domestic, not international, and while his policies can have significant impact on others, “America First” means how does it impact the US’ (or his own personal) bottom line, with little concern for the consequences to others. He also seemingly rejects any belief in US exceptionalism and all the burdens and responsibilities that it creates.

Most importantly, we have learned that you can’t take what he says at face value. Normally, if the president says something, it is usually seen as a policy pronouncement. But with Trump, it may just be a bargaining point, or a wild random thought, or even a deliberate lie (or “alternative truth”). Then-President Trump once referred to Chinese President Xi Jinping as a “brilliant leader” and “great man” only a few days after calling him an “enemy” who is ripping off America. When pressed about this inconsistency, he responded: “Sorry. It’s the way I negotiate,” further noting that “it’s done very well for me over the years, and it’s doing even better for the country.” Separating when he is speaking as “commander-in-chief” from when he is acting as “negotiator-in-chief” has been, and will remain, no easy task.

Someone once said “Wagner’s music is not as bad as it sounds.” The same can be said for Trump’s foreign policy in his first administration, if you focus on what he actually did and on stated policies in documents like the National Security Strategy, not tweets. Countering this somewhat comforting thought, however, is the fact that many of the internationalists surrounding and advising Trump during his first administration, like former Defense Secretary Jim Mattis, former-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, and his former UN Ambassador (and main primary opponent) Nikki Haley are not likely to be involved in the upcoming administration.

. . . based on what he’s saying and doing now.

While the world has changed in many ways since he was last president, there appears to be very little change in the way Trump sees the world.

While his relentless focus on the bottom line for the US and the disregard for other nations’ interests is often derided, the same can be said about virtually every national leader; they are elected (or self-appointed) to look out for their own country’s national interests, first and foremost. Americans like to believe we have been held, and/or have held themselves, to a higher standard. Trump, in this regard, is more like every other world leader, and less like the ideal picture we have painted for ourselves.

Trump is also doubling down on his America First mantra, based on the eclectic assortment of potential cabinet and other senior officials being proposed thus far (and remember, with the exception of his national security advisory staff, most face confirmation hearings, a task made easier, but by no means certain even with Republican control of the Senate). On the other hand, unlike many of his domestic-oriented choices, most of his national security choices, as noted above, are mostly internationalists who are more pro-alliance and pro-engagement, and more anti-authoritarian than Trump often appears to be.

Meanwhile, the hardening of anti-China sentiment, which grew during the first Trump administration and then was at least perpetuated if not intensified during the Biden administration, appears likely to continue to intensify, for economic and ideological reasons as well as security concerns. To be fair, a lot of this is driven not by US preferences or predetermination but by Chinese predatory practices and increased aggressiveness, which also seem destined to continue if not increase.

Even before the failed declaration of martial law (more on this below), South Koreans were nervously awaiting the onset of Trump 2.0. The sense of urgency that drove the Biden/Kishida/Yoon administrations (now all gone or going) to further institutionalize the Camp David agreements was to prevent backsliding if Trump were reelected. Koreans were also nervous about a possible renewed “bromance” between Trump and Kim Jong Un; Alex Wong’s selection as deputy national security advisor has added to this anxiety. Trump’s intentions and desires (or lack thereof) aside, one wonders if Kim would agree to another summit even if one were proposed. He’s already gotten what he desired most (international recognition) and is unlikely to agree on the next diplomatic step, which would be a visit to Trump’s home turf. It’s also hard to imagine Xi or Putin pressuring Kim to make nice with Trump, at least not while Ukraine is still boiling over and China-US relations remain strained.

Despite headlines to the contrary, what Trump plans to do about Ukraine is also unclear. His fascination with Putin aside, his pledge to end the Ukraine War on day one requires Putin’s acquiescence. Note that Trump spokesmen have claimed the two have spoken and Trump has told Putin not to make things worse, advice Putin has clearly ignored. While Trump is likely to cut back if not curtail US financial support to Ukraine, he is equally likely to remove remaining restrictions on Ukraine’s use of US-provided weapons if Putin drags his feet, thus making the great negotiator look bad. Only time will tell.

. . . but really don’t know!

While all that we have just said may very well continue to hold true, we must caveat it all by saying that, when it comes to Trump’s future policies, we are all guessing. Everything we just said could be wrong. Or, even if it is initially correct, it could change. Biden, like many of his predecessors, has had, among other senior Cabinet officials, the same national security advisor, secretary of State, and secretary of defense he began with four years ago. Trump, in his first term, had four national security advisors, two confirmed and four acting secretaries of state, two secretaries of defense, and four chiefs of staff. With each leadership change came subtle and, on occasion, not so subtle policy changes; again, stay tuned.

More importantly, recall the words of former UK Prime Minister Harold MacMillan, when asked what had been the greatest influence on his administration: “Events, my dear boy, events,” he replied. Trump’s first administration didn’t see COVID coming, and the Ukraine invasion and events of Oct. 7 and its aftermath in Gaza had a profound impact on the Biden administration. Who knows what great challenge lies just around the next corner?

Domestic Politics Spill Over

Speaking of surprises, while considerable column inches have been devoted to the impact of Donald Trump’s return to the White House, domestic political developments in other countries have potentially significant consequences as well. Two—the collapse of the Kishida government in Tokyo and the botched auto-golpe by South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol—warrant mention here.

LDP turmoil. Kishida’s government collapsed under the weight of accumulated scandal and policy incoherence. The political funds scandal that decapitated the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) was only the latest in a series of revelations about misbehavior that undermined public trust in the party. Kishida’s dithering response to the crisis exposed him as weak. His government’s inability to prioritize among competing objectives—increased defense spending, strengthening the social safety net, and more support for child care—further eroded public confidence.

The political funds scandal also deprived the LDP of its ability to organize party elections. The factions that were disbanded in the aftermath of the scandal served as the vehicle to distribute positions within the government and the party; without them, politicians were left to vote as they pleased in party elections rather than in accordance with the backroom decisions of senior officials who served as faction heads. This vacuum allowed Ishiba Shigeru, the five-term contender for party president, to prevail in the October party vote and then be elected as prime minister.

While qualified to serve as PM and holder of views that align him with the party (and national) mainstream, he is reviled by the rightwing of the LDP for being “the anti-Abe,” adopting political positions and a style that were the antithesis of Japan’s longest-serving prime minister. Days after Ishiba’s victory in the LDP vote, Taniguchi Tomohiko, Abe’s speechwriter who carries the flame for his former boss and speaks for the group within the LDP, published a commentary that essentially declared war on the new prime minister.

A little over a month into his tenure, Ishiba clings to power but the media focus on his weakness reflects both the reality of his government and some nudging from the right. The truth is Ishiba is weak, leading a minority government in which small opposition parties are trying to maximize their influence and the prime minister has little alternative but to try to accommodate them.

This matters for our purposes because Japan has played a key role in regional politics in recent years, following Abe’s lead and with support from the US to step up. It is not clear that he has the diplomatic chops or the political power to maintain that leading position in the region, a shortcoming that will become palpable if Trump runs roughshod through the Indo-Pacific and the US-supported alliance structure as he did in his first term. Moreover, it isn’t clear that Ishiba has the power to deliver on the promise of increased defense spending that Kishida made and which is likely to be a key factor in, if not determinate of, relations with the US.

Yoon’s self-inflicted disaster. The second important domestic political development is the botched coup launched by President Yoon in early December. Yoon was a weakened political figure before he committed that act of self-immolation, and now his fate is now in the hands of the Constitutional Court, which has up to 180 days to determine if the impeachment stands. If so (which seems likely), a new presidential election must be held within 60 days of the court’s ruling. Until then (and even if the impeachment is overturned), he is a husk of a leader.

Again, for our purposes the issue is the durability of his foreign policy after he leaves office, in particular the rapprochement with Japan that he engineered. Yoon displayed real vision and no small amount of courage to push that project, and while it is popular among the South Korean public, relations with Japan have proven susceptible to political manipulation and Yoon’s outreach to Japan has been severely criticized by the opposition. A politician determined to use history issues as a tool for advancement invariably finds fertile soil for such a strategy. A weakened partner in Tokyo and a disinterested White House could prove fatal to the rejuvenated bilateral and trilateral relationships.

More Multilateralism, Mostly under the Radar

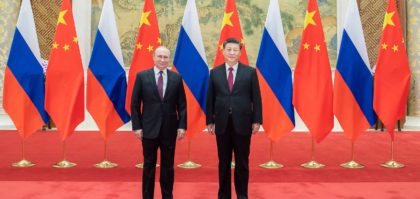

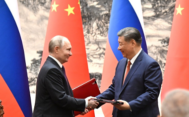

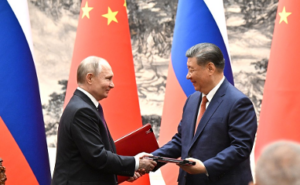

There were, as always in the last half of the year, several multilateral meetings of note. First in the list was the 16th BRICS summit, held Oct. 22-24 in Kazan, Russia. The summit was a pageant for several reasons. It was the first BRICS meeting to include Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates as members—nine in all—who were joined by another 29 guests/observers. Even more important was President Vladimir Putin’s role as host of the summit. That turnout and the continuing interest in the BRICS are proof that attempts to make Putin an international pariah have failed and he remains a powerful figure in world politics—and not only for his ability to wreak havoc and destruction.

The BRICS summit produced the Kazan Declaration. It called for “comprehensive reform of the UN, including its Security Council, with a view to making it more democratic, representative, effective and efficient,” condemned terrorism, expressed concern “about the rise of violence and continuing armed conflicts in different parts of the world,” and called for the peaceful resolution of conflicts. While endorsing an immediate ceasefire in the Gaza Strip, it was far less decisive when it came to the Ukraine war, merely recalling national positions on the Ukrainian crisis, and it “noted with appreciation relevant proposals” aimed at a peaceful settlement of the conflict through diplomacy. The statement also called for reform of the institutions of the global economic order, to reduce US influence (and that of the West more generally) and increase the role of developing countries.

Second was the APEC Economic Leaders Meeting on Nov. 15-16 in Lima, Peru. APEC represents 3 billion people – nearly 40%of the world’s population—and almost half of global trade and more than 60% of global GDP. That gathering produced the Machu Picchu Declaration, which detailed the usual objectives. As always, the leaders called for enhanced economic cooperation to promote sustainable and inclusive economic growth, and address regional challenges. In addition, the leaders endorsed the Lima Roadmap to Promote the Transition to the Formal and Global Economies (2025-2040) and the Ichma Statement on A New Look at the Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific Agenda. The leaders’ Declaration had a companion Chair’s Statement, which addressed, as in most other similar meetings, the discussion on Russia’s aggression in Ukraine and other geopolitical issues. Issuance of a separate statement reflects the inability of the group to reach consensus on those issues.

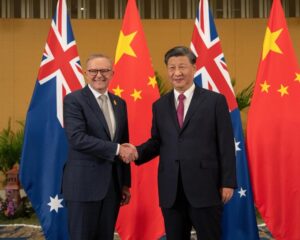

For the most part, the APEC meeting got little attention save for the seeming decline in US influence in Latin America. Considerable media space was devoted to the opening of a $3.5 billion megaport in Peru funded with Chinese money and President Xi’s attendance at that ceremony, a sign of growing Chinese influence in the region. Biden was described as “seemingly dazed” at the usual photo op, and thought to have been “dissed” when placed in the far back corner, between Thailand and Vietnam—even though the positioning is alphabetical.

Figure 2 Newly elected president Luong Cuong arrives at the National Assembly in Hanoi, Vietnam on Monday, Oct. 21, 2024. Photo: Minh Hoang/Associated Press.

The following week, many of those same leaders convened in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil for the annual G20 summit. The summit declaration hammered home the meetings three priorities: social inclusion and the fight against hunger and poverty, reform of the institutions of international governance, and sustainable development and the energy transition. The statement again failed to condemn the war in Ukraine—repeating the omission of last year’s declaration – because of Russian resistance. The leaders supported international trade and WTO reform, but the sections were lukewarm at best, calling for respect for rules without a forceful condemnation of protectionism. The climate sections were similarly tepid, again a product of a membership that includes major fossil-fuel producing countries. While more representative than other institutions of global order, we are inclined to agree with the observer who cautioned against expecting much of the G20, which because of its membership, is likely to “follow other international institutions in which little, if any, meaningful progress is made for the foreseeable future.”

Speaking of “little, if any, meaningful progress,” the 19th annual East Asia Summit convened in Vientiane, Laos on Dec. 6-11, absent a number of key leaders: the United States was represented by Secretary of State Tony Blinken, Russia by Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, and China by Premier Li Qiang. The Chairman’s Statement contained the usual bromides, reaffirming the importance of maintaining and promoting peace, security, stability, safety, and freedom of navigation in and overflight above the South China Sea,” expressing “deep concern over the escalation of conflicts and humanitarian situation” in Myanmar while reaffirming support for the ASEAN Leaders’ Five-Point Consensus (5PC), and expressing “grave concern over the dire humanitarian situation in Gaza, which has been exacerbated following the 7 October attacks.” Regarding Ukraine, “as for all nations, [the leaders] continued to reaffirm our respect for sovereignty, political independence, and territorial integrity” and “reiterated our call for compliance with the UN Charter and international law.” The leaders’ words largely echoed the comments earlier in the year in the ASEAN Regional Forum Chairman’s Statement, also attended by Secretary of State Blinken.

Ever More Military Cooperation, and Rising Dangers

Multinational ships sail in formation July 22, off the coast of Hawaii during Exercise Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) 2024. Twenty-nine nations, 40 surface ships, three submarines, 14 national land forces, more than 150 aircraft and 25,000 personnel are participating in RIMPAC in and around the Hawaiian Islands, June 27 to Aug. 1. The world’s largest international maritime exercise, RIMPAC provides a unique training opportunity while fostering and sustaining cooperative relationships among participants critical to ensuring the safety of sea lanes and security on the world’s oceans. RIMPAC 2024 is the 29th exercise in the series that began in 1971. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Larissa T. Dougherty)

One of the great dangers that stalks the Indo-Pacific region these days is the threat of a crisis emerging from mistake or miscalculation. The immediate danger stems from the gray-zone tactics pursued by governments that seek to gain advantage and shift the status quo in their favor by subtle means that remain below the threshold of conflict.

Almost as worrisome—if not more so—is the proliferation of military exercises throughout the region. Many of these drills are intended to signal commitment and readiness to defend alliance obligations, along with the expanding capabilities of the US and its allies as they work together in new ways. In June, US, Japan and ROK held the first trilateral Freedom Edge exercise, a multidomain exercise that was announced at the summit of the three leaders last year at Camp David as part of their efforts to deter evolving nuclear and missile threats from North Korea.

In September, the Royal Australian Navy, Air Force, Japan’s MSDF, Royal New Zealand Navy, the Armed Forces of the Philippines, and the US Navy conducted a Maritime Cooperative Activity (MCA) within the Philippines’ Exclusive Economic Zone in the South China Sea. The MCA included training on routine multilateral surface operations, deck landings, hoisting, and search and rescue.

At the 14th Trilateral Defense Ministers’ Meeting (TDMM) that was held Nov. 17 in Darwin, the ministers—Australian Minister for Defense Richard Marles, Japanese Minister of Defense Nakatani Gen, and US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin III—agreed to deepen defense cooperation by including Japanese forces in the annual US-Australia Talisman Sabre and Southern Jackaroo from next year. They also agreed to include or enhance Australia’s participation in annual US-Japan exercises That participation will boost “trilateral interoperability” among the three countries’ militaries. (Their statement also included the usual talking points on “commitment to a peaceful, stable, and prosperous Indo-Pacific region,” respect for rule of law, support for ASEAN centrality, concern about destabilizing actions by China and North Korea, the importance of peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait, and the like.)

The meeting announced establishment of the “Trilateral Defense Consultations” to support alignment of policy and operational objectives of the JSDF, the Australian Defense Force, and US forces from peacetime to contingency. The statement identifies ways to promote or strengthen trilateral cooperation from intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance cooperation in the Indo-Pacific region, enhanced trilateral air interoperability, Japan’s participation in AUKUS under pillar 2, and increased interaction among the three countries defense industries.

The next week, Australian Minister for Defense Industry Pat Conroy, Japanese DM Nakatani, Philippine Secretary of National Defense Gilberto Teodoro, Republic of Korea Minister of National Defense Kim Yong-hyun, and Secretary of Defense Austin met for the first time in Vientiane, Lao PDR, along the sidelines of the 11th ASEAN Defense Ministerial Meeting-Plus (ADMM+). They repeated the commitment to advance a vision for a free, open, secure, and prosperous Indo-Pacific, where international law and sovereignty are respected, and emphasized the importance of close multilateral cooperation to secure regional security and stability. (The ADMM+ meeting itself was largely uneventful, with the Joint Vision Declaration containing the usual platitudes about “peace, security, and resilience.”)

This spirit of cooperation was realized in December when the three militaries joined for Yama Sakura 87, which was held simultaneously with the first US Army Warfighter command post exercise held in Japan Dec. 6-14. YS 87 features the first full participation from the U.S. III Marine Expeditionary Force with expanded ADF participation for the second consecutive year. Participants in the US-Japan Extended Deterrence Dialogue took a side trip from their meeting to observe the exercise.

While strategists and planners cheer the cooperation and growing interoperability of their forces, the sheer volume of the exercises and the logistics involved court dangers. There is an extraordinary number of military assets crossing the region and the possibility that some could bump or collide without any genuine intent to do so is real, and exacerbated by the tendency of other governments to observe, and sometimes interfere, with drills as they take place. There is also a cycle of action and reaction as one country or group of countries holds drills and the ostensible target responds with its own exercises to show that it is not deterred or intimidated. A detailed list is available in the chronology, but note

- The tendency of North Korea to have missile tests immediately after the US and South Korea hold their drills (in May and June).

- China’s joint naval and air exercises around Scarborough Shoal the day after the five country MCA in Philippine waters.

- The increased tempo of China-Russia exercises in East Asia as the US and its allies step up their exercising in the region.

AUKUS, JAUKUS, ROKAUKUS, or ….

Finally, it is worth noting the continuing debate over the future of the Australia-UK-US (AUKUS) enhanced strategic partnership, the multidimensional agreement to cooperate among the three nations that is emerging as “the cool kids club for hard security in the Indo-Pacific.” Most attention has focused on Pillar 1 of the plan, which will transform Australia’s submarine force, and likely its defense industrial base as well. There have been doubts about the viability of the project, even as the three governments continue to voice support for it. The first set of obstacles have been overcome as the US modified restrictions on the export of advanced technologies that would blocked the entire project. Now, however, questions swirl around the capacity of the US industrial base and its ability to build the subs demanded by the deal. Simply put, it isn’t clear that the US can meet its own needs and that has US lawmakers concerned about the commitment to build boats for its ally. Supporters insist that all can be constructed, but the debate will continue.

Most experts believe that for all the attention to the subs, the substance of the AUKUS agreement is in Pillar 2, which aims to develop new defense technologies. This pillar has aroused the most interest among other countries when they contemplate joining the group. In May, the ROK government said that it was thinking of joining Pillar 2, and the US DoD announced the next month that Japan was being considered for membership as well. (In October, Tokyo sent observers to an AUKUS exercise.) In May, New Zealand was reported to be involved in “information gathering discussions” on joining but a decision was far off. That triggered a warning from China to Wellington about doing so.

In September, the three members said that they in discussions with Canada, Japan, and New Zealand about potential collaboration. Most of the reporting, however, suggests less enthusiasm about expanding the group, with an Australian diplomat characterizing the addition of members as “complicated.” Reportedly, the chief concern is dilution of the focus on getting Pillar 1 done, while information security remains a worry. Other observers note a shift in focus regarding Pillar 2, with the three governments indicating that the goal of the work in that area is now regulatory harmonization rather than product innovation. “They are quietly moving the goal posts,” explained Tom Corben of the US Studies Center in Sydney.

Logic and common sense would argue that all these exercises and initiatives would continue during the upcoming Trump administration since they support US national interests. It remains to be seen if this will indeed be the case. It also raises the question as to who will step up if the United States steps back?

US - Japan

May — December 2024Once Again, Leadership Transitions Challenge US-Japan Alliance

2024 closes with new governments primed to lead in the US and Japan. A surprise decision by Prime Minister Kishida Fumio to step away from leadership of his party in August led to an unprecedented race to succeed him. Nine members of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) fought for the chance to become president of the LDP on Sept. 27, and in a surprisingly tight race, Shigeru Ishiba won the honor and thus became the 102nd prime minister of Japan on Oct. 1. Within days, Ishiba called a Lower House election for Oct. 27. The LDP lost dramatically, and in the Nov. 11 vote in the Diet, Ishiba’s LDP and its partner Komeito formed a minority coalition government. The US similarly was in the throes of political contest. On Nov. 5, Donald Trump won a decisive victory in the presidential election, and in the days that followed, the Republicans were declared winners in both the House and the Senate as well.

While Trump’s inauguration will not be until January 2025, his transition team began immediately to announce candidates for his Cabinet and for the many political appointments needed to fill out his new administration. There was little doubt that this would be a far more robust challenge to the status quo than Trump marshaled during his first term.

The US-Japan alliance continues to be a fundamental feature of US strategy in the Indo-Pacific. The bilateral agenda for strategic coordination has grown considerably, and significant changes in Japanese defense preparedness are underway. US forces, too, are adapting to the needs of the growing military imbalance in the region. Trilateral US-Japan-South Korea security ties have deepened, and a new trilateral with the Philippines seems promising. Across the region and globally, the US and Japan have joined in broader coalitions of strategic cooperation. And yet, there is concern that this burgeoning agenda of strategic cooperation could flounder as domestic priorities take center stage in both Washington and Tokyo.

A Fall Full of Elections

The fall brought national elections in both Japan and the US, though under notably different circumstances. In Japan, a snap election came as a surprise, following Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s resignation, the subsequent LDP leadership race that elevated Shigeru Ishiba to power, and Ishiba’s abrupt decision to dissolve the Lower House. In contrast, the date of the US election may have been fixed and known, but the political landscape otherwise offered little predictability. President Joe Biden’s late decision not to seek reelection paved the way for Vice President Kamala Harris to step in as the Democratic nominee, only for former president Donald Trump and the Republicans to reclaim not only the presidency but also control of both the House and Senate.

Figure 1 Prime Minister Fumio Kishida and U.S. President Joe Biden shake hands at the White House on Friday. Photo: Masanori Genko / The Yomiuri Shimbun.

On Aug. 14, Prime Minister Kishida announced that he would not run for reelection in September’s LDP leadership race, setting the stage for a fiercely contested and unusually open competition. The race initially featured nine candidates but quickly narrowed to three frontrunners: Koizumi Shinjiro, who would have been Japan’s youngest prime minister; Takaichi Sanae, vying to become the first female prime minister; and Ishiba Shigeru, a seasoned politician marking his fifth bid for party leadership. Ishiba consistently led public opinion polls, reflecting strong grassroots support, but he had long struggled to win backing from fellow Diet members. In the Sept. 27 election, Takaichi emerged as the top candidate in the first round of voting, but in the second round, Ishiba narrowly secured victory. His unexpected win highlighted divisions within the LDP but also marked an effort among some members to turn the page on recent scandals and rebuild public trust.

On Oct. 1, Japan’s parliament formally elected Ishiba as prime minister. Just over a week later, on Oct. 9, Ishiba surprised many by calling a snap election for Oct. 27, a move that appeared aimed at capitalizing on his initial popularity, taking advantage of a fragmented opposition, and securing a stronger mandate for his leadership. However, the gamble backfired. On Oct. 27, voters handed the ruling coalition of the LDP and its junior partner Komeito a decisive defeat. The LDP lost power for the first time in 15 years. While the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan (CDPJ), led by former Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda, gained significantly, much of the attention was drawn to the unexpected rise of the Democratic Party for the People (DPP) and its leader Tamaki Yuichiro, whose strong performance underscored the shifting political landscape.

The failure of any party or coalition to secure a majority of seats in the Lower House left uncertainty about the shape of Japan’s next government. On Nov. 11, Prime Minister Ishiba won a parliamentary vote to remain in office, making him the leader of Japan’s first minority government in three decades. Governing without a legislative majority presents significant challenges. The opposition now controls key committees, including the influential Budget Committee, which could complicate efforts to secure funding for next year’s priorities. Public approval of Ishiba’s Cabinet remains low, though it has improved slightly from 32% in late October to 40% in mid-November, according to Kyodo polling. Questions abound about how Ishiba will navigate this precarious political environment, including the extent to which smaller parties like the DPP will influence his policy agenda. With Upper House elections looming in July 2025, Ishiba’s ability to maintain leadership and deliver results will be closely watched, both at home and abroad.

In the US, the 2024 election campaign began with an air of familiarity, as it initially appeared to be shaping up as a rematch of 2020 between Biden and Trump. On July 15, the Republican Party officially selected Trump as their presidential nominee, alongside Senator JD Vance (Ohio) as his running mate. Trump had been the presumptive nominee since March 12, when he secured enough delegates in the Republican primary race. Despite unprecedented challenges—including his conviction on May 30 for 34 felony counts of falsifying business records to cover up a sex scandal tied to his 2016 campaign—Trump solidified his hold on the party. His path to the nomination was further punctuated by two assassination attempts, the most prominent of which occurred just days before the Republican National Convention. On July 13, Trump was shot and wounded in his right ear during a public appearance but was released from the hospital shortly thereafter and attended the convention as scheduled. A second attempt on Sept. 15 in Florida, while Trump was golfing, was thwarted before the would-be assassin could get close to him.

As the incumbent, President Biden initially appeared to have a clear path to securing the Democratic Party nomination, facing no primary challengers. However, his performance in the first debate on June 27 raised serious concerns among voters and within his party. Biden appeared visibly unwell, with a strained voice and moments of hesitation that cast doubts about his age and ability to serve another term—despite being less than four years older than Trump. These concerns quickly translated into declining public support and growing unease among Democratic leaders. On July 21, Biden announced he would not seek reelection, citing the need for new leadership and endorsing Vice President Kamala Harris as the party’s nominee.

On Aug. 2, Vice President Kamala Harris officially secured the Democratic nomination at the party’s national convention, becoming the first woman of color to lead a major party’s presidential ticket. Four days later, she announced Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz as her running mate, a choice seen as an effort to balance the ticket with a Midwestern governor who had garnered bipartisan support in his state. Initial polling suggested strong public enthusiasm for Harris, with many Democratic voters rallying behind her historic candidacy and optimism about her chances in the general election.

However, the Nov. 5 election saw Donald Trump ultimately emerge victorious, defeating Harris by a vote margin of 312 to 226 in the Electoral College. Trump carried all the key swing states, including Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin, flipping several districts that had narrowly supported Biden in 2020. Nationwide, most areas showed a pronounced shift toward the right. The Republican Party not only reclaimed the presidency but also gained control of both the House and Senate, signaling a significant shift in American politics.

Looking ahead to US-Japan relations in 2025, new teams in both countries will take the lead in managing the alliance. In Japan, Prime Minister Ishiba, a former defense minister, has signaled his focus on defense by appointing four former defense ministers to key posts, including Takeshi Iwaya as foreign minister and Gen Nakatani as defense minister. On the US side, Trump’s cabinet nominees reflect a mix of experience and controversy. Senator Marco Rubio of Florida has been nominated for secretary of state, while former Army National Guard officer and Fox News host Pete Hegseth is Trump’s choice for secretary of defense. Rubio’s nomination is expected to sail through Senate confirmation, but Hegseth’s has drawn significant scrutiny over past allegations of sexual misconduct, excessive drinking, and financial mismanagement.

These new teams will inherit a complex and demanding alliance agenda, spanning bilateral priorities, regional security challenges, and pressing global issues.

The US-Japan Security Agenda

Bilateral security cooperation is burgeoning. Japan’s security review in 2022 produced a massive increase in security-related investments, including new conventional strike capability, improved operational integration and readiness for the Self Defense Force, and a new program of overseas security assistance. In January, the Japanese government agreed to purchase 400 land-based Tomahawk missiles, and in April, the Maritime Self Defense Force began training for their use. Deployment is expected in Japanese fiscal year 2025, which begins in April 1, a year earlier than originally planned.

Figure 2 South Korea, the US and Japan began their first trilateral multi-domain exercise on June 27, 2024, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) said, amid efforts to deepen security cooperation against threats from North Korea, recently emboldened by its deepening ties with Russia. Photo: Yonhap

A new Joint Permanent Operational Command will also be stood up in the coming fiscal year, a first for Japan’s three branches of armed forces. This will integrate Japanese military operations to respond jointly to aggression and will place a single combatant commander in charge of Japan’s military readiness. To match this Japanese move to enhance operational integration, the US Forces Japan will gradually match operational requirements to provide smooth integration of operations between Japanese and US forces.

Finally, the Japanese government has begun to provide overseas security assistance to its neighbors in an effort to enhance their capacity to meet the growing instability in the region. By the end of the Japanese fiscal year 2023, this assistance included support for surveillance, radar, and patrol boats provided to the armed forces of the Philippines, Malaysia, Bangladesh, and Fiji.

All told, the Japanese government committed to enhancing its spending to 2% of GDP by 2027 when the current five year build up plan will be complete. In its third year, the plan will require consistent revenue if it is to be successful. A new defense tax is under consideration in the Diet, and preliminary cooperation between the LDP, DPP, and Ishin no Kai has been reached.

The US has also led efforts to institutionalize trilateral military cooperation between the Japanese, South Korean, and US forces in multidomain exercises named Freedom Edge. These were initiated after a bilateral Japan-South Korean defense agreement was reached in June at the Singapore gathering of the IISS Shangri-La Dialogue. Two of these trilateral exercises have been held since then, one in June and another in November, bringing the air, maritime, and space forces of all three allies together for a combined exercise dedicated to cooperation in case of a contingency on the Korean peninsula.

Keeping the US and Japan in Regional and Global Alignment

Much of the bilateral effort over the past several years has been focused on building coalitions of like-minded countries to cope with the growing challenge to the rules-based order. Two sets of relationships were emphasized by the Biden Administration. The first was the recovery of the Japan-South Korea bilateral relationship and the strengthening of institutionalized trilateral cooperation between the US and its two northeast Asian allies. Consultations between National Security Advisors, Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Intelligence heads bolstered a shared vision of strategic cooperation. Presidents Yoon and Biden and Prime Minister Kishida also committed to a set of shared strategic principles, outlined in the Spirit of Camp David joint statement in 2023, that were then amplified in November 2024 in a second leader’s meeting with Prime Minister Ishiba attending on the sidelines of the APEC meeting in Peru. In addition to the regular trilateral military exercises, noted above, the three leaders agreed to create a secretariat designed to facilitate trilateral cooperation.

Figure 3 US President Joe Biden hosted Australia’s Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Japan’s Prime Minister Fumio Kishida for the latest summit of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) in Wilmington, Delaware on September 23, 2024. Photo: South China Morning Post

Second, Japan and the US worked closely on building stronger ties among the Quad nations: US, Japan, Australia, and India. Leaders’ summits began in 2020 virtually but then became annual in-person meetings in 2021. In 2024, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese joined Japanese Prime Minister Kishida in Wilmington, Delaware to honor President Biden’s support of the Quad. A full agenda of Quad projects has developed over time, largely focused on aiding the Indo-Pacific nations in the provision of healthcare, infrastructure development, maritime domain awareness, and other collective goods required for regional stability. India is expected to host the 2025 Quad Leaders meeting.

Of course, concerns loom large over the fate of Taiwan. The US and Japan will continue to consult on the increased Chinese military exercises around Taiwan. Much of this is interpreted as pressure on President William Lai Ching-te. For example, a recent surge of Chinese military activity around Taiwan occurred shortly after Lai’s first overseas trip, which included visits to Pacific Island nations and transit stops in Hawaii and Guam—moves that were widely expected to elicit a strong response from Beijing.

But the growing assertiveness of China’s military beyond the Taiwan Straits continues to prompt enhanced security cooperation among US, Japanese, and other national forces. Chinese maritime pressure on the Philippines has also grown, challenging their maritime defenses and drawing a US restatement of its commitment to the US-Philippine alliance. During his fourth visit to the Philippines in November 2024, Secretary of Defense Austin announced the establishment of an information sharing agreement with the Philippines, designed to enhance the ability of the US and the Philippines to have real-time information on the activities of Chinese forces. Over the course of 2024, the PLA Navy has also increased its activity in and around Japanese waters, and Chinese-Russia strategic exercises have also increased. In August, Chinese government survey vessels intruded repeatedly into Japanese waters.

Conclusion

As the Ishiba Cabinet seeks to navigate its difficult position in the Japanese Diet, a second Trump Administration prepares to take the reins in the US. Trump’s Cabinet picks have created controversy already, and there is a sense that a major shakeup is coming to Washington. How this will affect US foreign policy remains to be seen, and personnel responsible for the day-to-day management of US Asia policy have yet to be identified. On the surface, however, there is little to suggest that the US-Japan alliance will suffer from a second Trump Administration.

Two issues will likely be of deepest interest to alliance watchers. The first is President-elect Trump’s position on tariffs and on trade more broadly. His announcement after his electoral victory that he is looking to place 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico and “an additional 10% tariff, above any additional tariffs” on China will, of course, have spillover effects for many countries. Japan’s automakers have a stake in however the Trump Administration seeks to revamp the USMCA trade agreement, up for review in 2026. More short term, the political hot potato of the purchase of US Steel by Nippon Steel will be determined by the CFIUS decision expected on Dec. 18. President-elect Trump has stated he will reject the deal.

Figure 4 Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida meets with U.S. President Joe Biden and other Group of Seven leaders at NATO Headquarters in Brussels in March. Photo: REUTERS

Burden-sharing will also likely be on the agenda for the US-Japan alliance, as it will for the NATO allies. Already, there are rumors that the NATO commitment to spending 2% of GDP on defense might be raised to 3% in a new Trump administration, again with possible spillover effects for US Indo-Pacific allies. The five-year Host Nation Support agreement between the US and Japan is set to expire in 2027 and thus will need to be renegotiated during the next administration.

But it is likely the larger questions of US strategy under the Trump administration that will be of most concern. Three foreign policy areas are particularly important for Japan. First, US strategy toward China will be of deepest import to Tokyo. Given that Japan has identified China as its gravest strategic threat, Washington’s choices and how much Japan’s interests will be considered in those choices are paramount. Second, how the US decides its role in Ukraine and in the larger context of European security remains to be seen. Japan has committed extensive resources to Ukraine and to the effort to rebuild the nation. Similarly, Japan, like other G7 nations, has imposed sanctions on Russia, drawing retaliation from Moscow. Finally, Japan has a deep stake in the global economy and relies on a free and open global order. A retreat to mercantilist practices would have devastating effects on Japan’s future economic prosperity. Of course, the LDP will face yet another election next year, and Prime Minister Ishiba will have to juggle pressures from within to keep on top of the domestic dynamics at play in Tokyo even as he seeks to ensure a strong US-Japan partnership under a second Trump Administration.

US - China

May — December 2024Trump’s Return Scrambles Outlook

US-China relations through 2024 remained marked by a paradox. On the one hand, ties displayed a distinct stabilization. The two sides translated their leaders’ modest “San Francisco Vision” into reality. Cabinet officials and the numerous working groups met in earnest and produced outcomes, functional cooperation was deepened though differences emerged, sensitive issues were carefully managed, and effort was devoted to improving the relationship’s political optics. US electoral politics, or threat of Chinese interference in the elections, did not materially impinge on ties. On the other hand, the negative tendencies in US-China relations deepened. With its time in office winding down, the Biden administration went into regulatory overdrive to deepen the “selective decoupling” of the two countries’ advanced technology ecosystems. China methodically responded in kind using its now-robust economic lawfare toolkit. The chasm in strategic perceptions remained just as wide. Donald Trump’s return to the Oval Office portends a period of disruptive unpredictability in ties, although “Tariff Man” Trump can reliably be expected to enact additional impositions on Chinese imports.

Two years to the day that they met on the sidelines of the G20 summit in Bali, Indonesia to place a floor under their troubled relationship and initiate a process of emplacing guardrails, Joe Biden and Xi Jinping met for their third in-person meeting as presidents in Lima, Peru, on the sidelines of the APEC Economic Leaders Meeting. In Lima, the two presidents took stock of the gradual rehabilitation of ties over the past two years, despite its early interruption by the balloon incident, and pledged to consolidate the fragile stability and make the relationship more predictable. They also patted themselves for harvesting some of the low-hanging fruit since their summit in Woodside, California, 12 months ago. US-China relations have made important incremental progress over the past 18 months, starting with Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s visit to Beijing in June 2023 (Blinken returned to Beijing again this April). In Spring 2023, aside from meetings of their senior-most officials, there was practically no active communication channel between the two sides. Fast forward to today and there are more than 20 dialogue frameworks that span the range from diplomacy, security, economy, trade, fiscal affairs, finance and military to counternarcotics, law enforcement, agriculture, climate change, and people-to-people exchanges.

Figure 1 US President Joe Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping greet one another prior to a bilateral meeting on Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024 in Lima, Peru. Photo: Official White House Photo by Oliver Contreras

In Spring 2023, the US Treasury Department was sanctioning Chinese entities for their involvement in supplying chemical precursors to US-bound fentanyl trafficking networks. Today, 55 dangerous synthetic drugs and precursor chemicals have been class scheduled by Beijing, online platforms and pill presses shut down, and arrests connected to the illicit chemical industry made. Reciprocally, China’s Ministry of Public Security-linked Institute for Forensic Studies has been delisted from the Entity List—a rare case of an adversary state entity being delisted without any underlying change in the listed reason for its blacklisting.

In Spring 2023, US-China people-to-people as well as academic ties were frail, having suffered body blows stemming from the polemics associated with the origins of the COVID-19 virus and the Justice Department’s earlier “China Initiative.” There were only 12 weekly roundtrip passenger flights in service. Today, the two sides are on the verge of renewing their landmark Science and Technology Agreement (STA), the first major agreement to be signed by the two governments following the re-establishment of diplomatic relations in January 1979, pandas are returning to zoos in San Diego, Washington, DC and San Francisco, the number of roundtrip passenger flights has risen to 50 (prior to COVID-19, the number exceeded 150), and the health authorities of the two countries recently held their first ministerial-level dialogue in over seven years. The cases of “wrongfully detained” Americans have been resolved (although many others remain on exit bans), reciprocal repatriations of illegal migrants and fugitives have been conducted, and the Mainland’s Level 3 travel advisory status (Reconsider Travel) has been lowered to Level 2 (Exercise Increased Caution) by the State Department. For his part, President Xi has committed to inviting 50,000 young Americans to China on exchange and study over the next half-decade.

Figure 2 A screenshot from a Smithsonian National Zoo video showing the FedEx truck driving through Washington, DC transporting two pandas newly arrived from China on October 15, 2024. Photo: National Zoo via X/Twitter

In Spring 2023, US-China climate change discussions—a mutually beneficial area of cooperation – were at a standstill and would only resume after the visit to Beijing by Special Climate Envoy John Kerry in July 2023. Today, the US-China bilateral Working Group on Enhancing Climate Action in the 2020s has met twice and, in keeping with their Sunnylands Statement of November 2023, the two parties jointly hosted a Methane and Other Non-CO2 Greenhouse Gases Summit at COP 29 in Baku, Azerbaijan. In Spring 2023, the idea of hosting exchanges on AI hadn’t even been broached, even as US and Chinese organizations were moving forward with transformative breakthroughs in Generative AI. Today, the two sides have begun a constructive and candid policy dialogue on AI, co-sponsored each other’s resolutions on AI at the UN General Assembly, and affirmed the need to ensure that unsupervised AI must not allowed to dictate command-and-control of critical weapon system – especially the decision to use a nuclear weapon. The fear that China would be treated as a political football during the US election season or that it would interfere in the elections using disinformation operations did not materialize either (although there may have been interference in down-ballot races).

For all the positives that have flowed from their newly established or restarted dialogue frameworks, not all conversations ended in constructive outcomes. This is understandable. As the “new normal” in US-China relations takes shape, there is no one typology of interaction that can cut across the various “baskets” of US-China issues. A complex relationship demands complex choices that are built as much on ideology and values as much on interests, objectivity and realism.

Mil-Mil Conversations Go Sideways on Strategic Arms Proliferation Concerns

The decision to restart mil-mil communications at the Biden-Xi Woodside summit in November 2023 was a bright spot in bilateral ties, to the extent that “jaw-jaw” is vastly preferable to “war-war.” Mil-mil ties had been suspended by China, it bears remembering, following Speaker Pelosi’s visit to Taipei in August 2022. This included the Military Maritime Consultative Agreement (MMCA) talks, an operational safety dialogue between US INDOPACOM and PLA naval and air forces, which had convened regularly since 1998. The full range of institutionalized high-level mil-mil communications stand restored as of this writing.

In January and September 2024, the 17th and 18th editions of the Defense Policy Coordination Talks, an annual deputy assistant secretary level policy dialogue, were respectively conducted. The MMCA working group met earlier in April and again in November, and a theater commanders video-teleconference featuring the Commander of the US Indo-Pacific Command and the PLA’s Southern Theater Commander was held in early-September (the two met later in September at the Indo-Pacific Chiefs of Defense Conference in Hawaii). Topping these engagements was the first in-person meeting between the two countries’ defense chiefs, Secretary Lloyd and Minister Dong, in a year-and-a-half on the margins of the Shangri La Dialogue (SLD) in late-May. While both sides had tough words for the other in their SLD remarks, they also agreed to convene a crisis communications working group by the end of 2024. For added measure, National Security Advisor Sullivan was afforded the opportunity to meet the Vice-Chairman of the Party’s Central Military Commission (CMC), Zhang Youxia, during his late-August visit to Beijing, the first such NSA-CMC vice chair meet in eight years.

The mil-mil communications were wholesome but could not mask the wide chasm between the two sides on strategic arms-racing and deterrence concerns. It was reported in August that Biden had reoriented a highly classified US nuclear strategic plan, the Nuclear Employment Guidance, in March 2024 to account for an era of multiple nuclear-armed adversaries in the context of China’s rapidly growing nuclear arsenal. Whether linked or not, China discontinued the bilateral arms control and nonproliferation consultations in July (lamely using Taiwan arms sales card as an excuse) and, later that month, unleashed broadsides against AUKUS’ nuclear submarine cooperation pillar as well as NATO’s nuclear sharing arrangements (it issued a No-first-use Nuclear Weapons Initiative too). It also conducted its first ICBM test in 44 years in late-September, with the projectile splashing down in the South Pacific. The US and China also clashed over the deployment of the Typhon Mid-Range Capability missile system in the Philippines. The US side cautioned the PLA for its dangerous, coercive, and escalatory tactics in the South China Sea which could trigger Article V of the US-Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty; the Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson admonished the US side for the first deployment of a strategic offensive weapon system outside its territory and in the Asia-Pacific since the end of the Cold War.

Careful Management on Taiwan Amidst Lobbing of Rhetorical Salvos

The Taiwan Question remained a bone of contention in US-China relations during the mid and latter part of 2024, to nobody’s surprise. In early-May, China’s foreign ministry spokesperson blasted Secretary Blinken’s encouragement as well as that of seven other allied nations to the WHO to invite Taiwan as an observer at the 77th World Health Assembly meeting. Later that month, the ministry spokesperson “deplore[d] and oppose[d]” Blinken’s note of felicitation to Lai Ching-te on his inauguration as president of the self-governing island. Lai had angered Beijing by noting that “the PRC and the ROC are not subordinate to each other” in his inaugural address. He was called out by name; treatment that took Beijing three years to mete out to his predecessor Tsai Ing-wen.

The Biden administration, for its part, was critical of the PLA’s Joint Sword 2024 A and B military exercises that were conducted in the wake of Lai’s inaugural address in May and his “Double Ten Day” address in October, respectively. Joint Sword 2024-A had focused on seizing the initiative in the Taiwan Strait battlefield, with the training content aimed at precision strikes on critical land, air and sea targets; Joint Sword 2024-B featuring the PLA Navy and the Coast Guard sought to execute a blockade of ports and other key locations. The exercises were denounced as “irresponsible, disproportionate and destabilizing.” The Biden administration also strongly condemned the June 2024 judicial guidelines issued by China’s Supreme People’s Court which imposes criminal punishments on “diehard Taiwan independence separatists” for conducting or inciting secession, noting that threats and legal warfare would not achieve peaceful resolution of cross-strait differences. And in conjunction with like-minded ANZUS, NATO and Japanese government allies, the US State Department sought to develop a common front to debunk China’s conflation and “mischaracterization” of UNGA Resolution 2758 with its “One China Principle.” China’s foreign ministry was having none of it, and political parties at the National Assembly in Taipei too were unable to arrive at a consensus on this point. All along, the Biden administration maintained a consistent clip of arms sales to the island, including by utilizing presidential drawdown authority, as well as periodic transits through the Taiwan Strait in international waters and airspace. China, for its part, built out its Taiwan arms sales-related list of sanctioned US parties under the framework of its Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law.

Figure 3 A schematic diagram of the area of the military exercise “Joint Sword 2024B,” released by the Eastern Theater Command. Photo: Ministry of National Defense of the People’s Republic of China, Public Domain

Tit-for-tat skirmishes between the two sides were not the whole story on the Taiwan Question. In Lima, Peru, Biden again assured his counterpart that the US does not support Taiwan independence (Xi had attempted—unsuccessfully—in Woodside to alter the phraseology to “oppose Taiwan independence’) and added that the US does not use the Taiwan card to compete or contain China. More broadly, Biden yet again reemphasized his “Five Noes’: that the US does not seek a Cold War with China; does not seek to change China’s system; the revitalization of its alliances is not directed at China; does not support Taiwan independence; and does not seek conflict with China. Whether believed or not in Beijing, these assurances offer a steadying framework for future-oriented ties.

Playing Cleanup on Advanced Technologies Decoupling

In an important speech in September 2022, NSA Jake Sullivan had listed three “families of technologies” —computing related technologies; biotechnologies and biomanufacturing; clean energy technologies—as “force multipliers” that would define the geopolitical landscape of the 21st century. Given their foundational nature, the US would seek to “maintain as large a lead as possible” over adversary nations, including by resorting to a “small yard, high fence” approach on strategic trade controls. Following the speech, the US Commerce Department issued an expansive regulation that instituted controls on China’s access to advanced computing chips as well as semiconductor manufacturing equipment essential to producing such chips.

With the clock winding down on its term in office, the Biden administration maintained its frenetic rulemaking pace, issuing a number of regulations in quick succession to deepen the “selective decoupling” of the two economies’ advanced technology ecosystems. On Sept. 23, the administration released a Proposed Rule to secure the supply chain for connected vehicles, which prohibits the import of Chinese hardware and software integrated into vehicle connectivity system (VCS) and software integrated into automated driving system (ADS). VCS is the set of systems that allow the vehicle to communicate externally, including telematics control units, Bluetooth, cellular, satellite, and Wi-Fi modules. The ADS includes the components that collectively allow a highly autonomous vehicle to operate without a driver behind the wheel. The Proposed Rule follows an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPRM) issued earlier this February.

On Oct. 29, the US Justice Department issued a massive 422-page proposed rule to prevent access to Americans’ bulk sensitive personal data as well as government-related data by countries of concern, such as China. The rule proposes to establish a new national security-based regulatory regime governing the collection and transfer of personal data. Two types of commercial transactions between a “US person” and a “country of concern” are to be prohibited – transactions involving “data brokerage” (with the term defined broadly) and transactions involving human genomic data. The proposed regulation contains an exemption for certain data transfers in connection with biopharmaceutical clinical investigations and post-marketing surveillance data. The Proposed Rule follows a White House executive order accompanied by an ANPRM issued earlier this March. It also follows instances of damaging cyberespionage breaches by China-linked hackers, which include the infiltration of US broadband providers” networks to sweep up the private communications of hundreds of thousands of Americans as well as access the “lawful intercept” system maintained by the Justice Department to place wiretaps on suspected Chinese spies in the US. Earlier in July, the “Five Eyes” countries, joined by Germany and Japan and South Korea for the first time, had issued a rare joint advisory attributing malicious cyber activities to China. President Xi, for his part, disavowed any such conduct in his Lima meeting with Biden, with his foreign ministry spokesperson having earlier thrown the ball back into the US’ court.

Also on Oct. 29, the US Treasury Department released a voluminous final rule to prohibit outbound investment in semiconductors and microelectronics, quantum information technologies, and AI systems to China. The purpose of the Outbound Order is to shut down a pathway for Beijing to exploit the “intangible benefits” – including enhanced standing and prominence, managerial assistance, investment and talent networks, market access, and enhanced access to additional financing – that accompany the flow of US investments to China. The order marks the first instance of the US government controlling outbound capital flows for national security reasons. And while the regulation is framed as addressing capital flows, it effectively regulates the coverage of “greenfield” and “brownfield” investments in these national security technologies and products, too. The Final Rule follows a White House Executive Order issued in August 2023 and a Proposed Rule issued earlier this July.

Finally, on Dec. 2, the US Commerce Department issued a final rule that upgrades the existing controls on China’s access to semiconductor manufacturing equipment so as to impair its capability to produce advanced node semiconductors. Twenty-four types of semiconductor manufacturing equipment and three types of software tools are to be additionally denied to Chinese end-users. Beijing response to the measure was swift. On Dec. 3, it announced a ban on several minerals essential to semiconductor, communications and military technologies, as well as a prohibition on exports of dual-use items to US military end users. Alongside the semiconductor manufacturing equipment rule, the US Commerce Department also imposed controls on the transfer of high-bandwidth memory (HBM) chips, which are crucial for accelerating AI training and inference as well as added 140 entities spanning tool companies, chip fabs and investment firms to the Entity List. Earlier this May, a number of Chinese quantum technology companies and research institutes had been added, too, to the List. Overall, the number of Chinese entities placed in the Entity List during the 2018-2023 period have increased over 300% (from 218 to 787). As for license applications submitted that involve a Chinese Entity List-ed party, they increased from five in 2018 to a high of 1,751 in 2021, with approximately 33 percent of applications either denied or revoked.

In addition to these advanced technologies and data flow controls, successive rounds of sanctions were enforced on China for its policies on “forced labor” in Xinjiang and support for Russia’s war in Ukraine. This included the first US sanctions imposed on a Chinese entity for joint development and production of a complete weapon system (the Garpiya series long-range attack unmanned aerial vehicle) with the Russians. No Chinese financial institutions have as yet been sanctioned, despite Secretary Blinken’s threat to do so in his late-April meetings in Beijing. To the contrary, the US Treasury Department and China’s Finance Ministry maintain a cordial working dialogue that spans the range from financial sector operational resilience to debt relief for low-income countries to central bank scenario testing of climate change risks. Earlier in April, the two sides had established dedicated workstreams on Balanced Growth in the Domestic and Global Economies and on Cooperation and Exchange on Anti-Money Laundering under the aegis of their financial and economic working groups.

“Small yard, high fence” export controls has been one component of the Biden administration’s toolkit to vigorously compete with China in the advanced technologies of tomorrow. Alongside, the administration also passed landmark legislation, such as the CHIPS and Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), as well as employed an impressive array of industrial policy authorities, such as the Defense Production Act, Buy American Act and the Bayh-Dole Act, to incentivize the expansion of domestic productive capacity in key strategic and high value-added manufacturing industries. To this end, and in its waning days in office, the administration aggressively pushed out CHIPS Incentives Awards totaling in the many billions to the likes of Intel, BAE Systems, GlobalFoundries, and TSMC. There are uncertainties whether this industrial buildout will continue under President Trump and a Republican Congress, particularly with regard to the proposed IRA project investments (fully 80% of announced Korean and Japanese investments are tied to IRA money). Trump had vowed to “terminate” the IRA on the campaign trail and no Republican supported passage of the legislation in 2022. On the other hand, three-quarters of announced investments are in Republican-controlled districts and 65% of them located in counties that voted for Trump.

China Responds in Kind

China was active on the “selective decoupling” front too in 2024, having methodically built a robust economic lawfare toolkit over the past five years. These include the Unreliable Entities Regulation (Sept. 2020), the updated National Security Review Mechanism (Dec. 2020), the Unjustified Extraterritorial Measures Regulation (Jan. 2021), the Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law (June 2021), and more lately, a new Dual-Use Export Control Regulation (September 2024) under the framework of its Oct. 2020 Export Control Law. Having absorbed blow after blow of US technology denial measures, China began deploying these tools in earnest in 2024. In March 2024, new procurement guidelines were introduced phasing out foreign operating systems, microprocessors and database software from government PCs and servers. In May, the Cyberspace Administration of China banned the use of the US semiconductor firm Micron’s products in China’s critical information infrastructure following a failed cybersecurity review. There have been calls for a cybersecurity review of Intel too and more lately, a coordinated advisory issued by four Chinese industry bodies to discontinue the usage of US-made chips given that they are “no longer safe.”

In August, the Ministry of Commerce (MofCom), announced export controls on antimony, a critical mineral with military and civilian applications including battery storage. The antimony controls follow on the heels of controls on gallium, germanium, and high-purity natural and synthetic graphite materials introduced in 2023. These controls were effectively upgraded in early-December 2024 to a full ban “in principle” vis-à-vis the US following the latter’s imposition of export controls on China-destined semiconductor manufacturing equipment. Controls on “superhard materials” such as industrial-grade diamonds and tungsten carbide, used in chip manufacturing-related cutting, grinding, and polishing processes, is anticipated to be the next export control shoe to drop. In September, MofCom announced an investigation into the US parent company of Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger under its Unreliable Entity List mechanism for its exclusion of Xinjiang-originating cotton from supply chains. And in October, sales of key Chinese battery components to the largest US drone maker, Skydio, was revoked under the Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law for its role in arms sales to Taiwan, forcing Skydio to ration batteries to one per drone to customers.

Wave-upon-wave of Taiwan arms-sales related countermeasures against US military companies and senior executives were imposed too in April, May, June, July, September, and December by China’s foreign ministry under its Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law. For added measure, General Atomics Aeronautical Systems, General Dynamics Land Systems, and Boeing Defense, Space & Security were separately added to the Commerce Ministry’s Unreliable Entities List in May. In February 2023, Lockheed Martin and Raytheon Missiles & Defense became the first US entities to be placed on this list for their role in arms sales to Taiwan. The upshot is clear: China’s countersanctions and reciprocal export control regime is being ramped up which will inevitably lead to more US (and foreign) companies being caught in the crossfire between the US and Chinese regimes.

Doubling-down on Section 301 Tariffs

Trade frictions returned to the fore in US-China relations during the latter half of 2024. The first shot of this new great power rivalry, it bears remembering, was fired in the trade policy arena in the Summer of 2018 when the Trump administration introduced Section 301 List 1 tariffs on $34 billion of Chinese imports. In total, $370 billion of Chinese imports spread across four lists were thereafter subjected to tariffs, with China imposing lesser retaliatory tariffs also. On May 14, 2024, following a statutory four-year review of the Trump-introduced tariffs, the Biden administration not only retained the tariffs but selectively augmented them to the tune of $18 billion for semiconductors, electric vehicles, batteries, battery parts and critical minerals, solar cells, and certain personal protective equipment (final modified rates were notified in September). Concurrently, the White House and the Treasury Secretary accused China of engaging in non-market practices that was creating excess supply to the detriment of industry and workers abroad. China was failing to meet its industrial subsidies-linked notification requirements at the WTO too, especially regarding proliferation of sub-central level “public-private investment funds” which were driving this structural overcapacity. The additional Section 301 tariffs were justified, in the administration’s telling, to protect the historic Chips Act and IRA investments in strategic sectors (semiconductors, batteries, EVs, solar, medical equipment) from being unfairly undercut by Chinese exports.

The administration’s accusations are not without merit. China’s domestic savings remains excessively high. The fear that these excess savings (and domestic under-consumption) will macroeconomically manifest itself in the form of overproduction that is dumped overseas is genuine. And because a component of this overproduction is the product of non-transparent industrial subsidies, this would amount to unfair trade-distorting competition in international markets. Beijing rejects this characterization. In its view, the current global production landscape is the result of market competition and the international division of labor. Within China, competition in its new energy marketplace is intense; as such, only the fittest survive and therefore tend to prosper in international markets. Export volumes too should not be taken as a benchmark for determining overcapacity either. US, Japan, and Germany’s auto exports for instance account for 23%, 75%, and 50%, respectively, of domestic production; China’s EV exports by comparison account for only 12.5% of production. Besides, there is a huge demand for new energy products in global markets, and it is the fragmentation of global industrial and supply chains due to the adoption of discriminatory subsidy measures by the West that is the primary contributor to “so-called overcapacity,” Beijing counters. China’s subsidy programs adhere to fair competition and non-discrimination rules, are mainly for R&D, are targeted at the consumption end, and are not contingent upon export performance. The WTO secretariat and the European Commission might beg to differ with some of these contentions.

Figure 4 A Donald Trump impersonator standing in front of the White House in Washington, DC in a mask and pointing at the camera. Photo: UnSplash, CC2.0

The Return of “Tariff Man” and the Uncertain Future of Bilateral Ties

“I am a Tariff Man. When people or countries come in and raid the great wealth of our Nation, I want them to pay for the privilege of doing so. It will always be the best way to max out our economic power. We are right now taking $billions in Tariffs. MAKE AMERICA RICH AGAIN.”

So tweeted President Donald Trump, three days after a tense but positive meeting with President Xi on the sidelines of the G20 Summit in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in December 2018 as the two sides tried to head-off tit-for-tat tariffs on billions of dollars of bilateral trade.