Articles

US - Southeast Asia

US relations with Southeast Asia ended on a down note in 2023 with the last-minute failure to finalize the trade pillar of the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF). This was not a complete loss for ASEAN states that managed to negotiate bilateral supply chain resilience agreements. However, it underscored the fact that broad regional frameworks, particularly for trade, are off the table with Washington, at least until the United States is past the November 2024 elections. Instead, the administration focused on security over trade and on key partners in the region, with Biden skipping the East Asia Summit (EAS) in Jakarta for a visit to Vietnam and the announcement of the US-Vietnam Comprehensive Strategic Partnership. In this period, US relations with the Philippines continued to strengthen, with Washington issuing three statements calling out China for its reckless maneuvers in the Philippines’ Exclusive Economic Zone in the South China Sea. But if some Southeast Asians were miffed by the administration’s focus on bilateralism over regionalism, most were reassured by Biden’s meeting with Xi Jinping on the margins of the APEC meeting in San Francisco.

US - Southeast Asia

May — August 2023New Leaders Challenged by US-China Rivalry

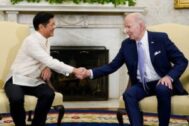

Over the summer three Southeast Asian nations—Thailand, Cambodia, and Indonesia—conducted political contests or prepared for them, with Washington and Beijing watching closely for shifts in alignments or opportunities to make inroads with new leaders. Despite this, and possibly because of it, China made bold moves in the South China Sea and caused outcry in the region with the release of a map supporting its claims to the “Nine-Dash Line.” Beijing also showed signs of worry about Russian inroads into Southeast Asia and the Indo-Pacific region. The high-profile visit to Washington of Philippine President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, Jr. enabled both countries to reconfirm the US-Philippines alliance publicly, although it gave little indication of where the broader relationship may be headed. ASEAN continued to make little headway in helping to resolve the conflict in Myanmar; and the 2023 chair, Jakarta attempted to redirect the group toward economic goals and a common approach to looming food insecurity in the region.

US - Southeast Asia

January — April 2023Washington Zeroes in on Manila

With an apparent renaissance in the US-Philippine alliance, spurred by rising tensions in the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait, the Biden administration ramped up diplomatic activity with Manila as the two countries moved toward an official visit from President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, Jr., in May. At the same time, the 42nd iteration of Cobra Gold, which returned to full strength for the first time since the 2014 coup in Bangkok, suggested momentum in the US-Thailand alliance, albeit with a lower profile. While the international environment continued to be roiled by US-China rivalry, the Russian war in Ukraine, and high food and commodity prices, Southeast Asia’s own internal turmoil was evident. The junta in Myanmar extended the state of emergency and stepped up aerial bombing of areas held by the opposition and armed ethnic groups. As Indonesia takes up the ASEAN chair, prospects for implementing the Five-Point Consensus Plan are dim, if not dead. Vietnam and Thailand began leadership transitions—Hanoi with an anti-corruption purge and Bangkok with the launch of general elections—while Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen continued to eviscerate the opposition ahead of his near-certain re-election in July.

US - Southeast Asia

September — December 2022External Order, Inner Turmoil

In November three ASEAN states—Cambodia, Indonesia, and Thailand—drew favorable marks for their chairmanship of high-profile regional and global meetings: the East Asia Summit and ASEAN Leaders Meeting; the G20 Summit; and the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) meeting, respectively. Helming these meetings was particularly challenging for Southeast Asian leaders—who are naturally inclined to avoid strong alignments with external powers—in the current global environment of heightened tensions between the United States and China in the Taiwan Strait and the war in Ukraine. However, the year was a difficult period for ASEAN internally, with uneven economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic and the intractable conflict in Myanmar. The last quarter of 2022 saw two political shifts in the region: in general elections in Malaysia, Anwar Ibrahim achieved a longstanding ambition to become prime minister but will have to manage a difficult coalition to retain power. At the year’s end, Laos changed prime ministers, but it is not clear if the transition will solve the country’s debt problems, which were revealed to be more dire than estimated.

US - Southeast Asia

May — August 2022Washington Revs Up Diplomacy with Southeast Asia

The Biden administration’s diplomatic campaign in Southeast Asia kicked into high gear in the late spring and continued through the summer. On May 12-13 President Biden co-hosted, with Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen as the 2022 ASEAN chair, the first-ever US-ASEAN Special Summit to be held in Washington, DC. US relations in the region were also boosted when the Biden administration launched the long-awaited Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) on May 23; seven Southeast Asian countries indicated interest in joining, although few are likely to accede to all four pillars of the framework in the near-term. Two Cabinet officials made visits to two US treaty allies: Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin to Thailand in June and Secretary of State Anthony Blinken to the Philippines in August. Notwithstanding continuing differences over human rights, the visits served to reaffirm the bilateral alliances. However, global and regional tensions remained high, over the persistent crisis in Ukraine; brinksmanship in the Taiwan Straits; and the internal conflict in Myanmar which has only deteriorated further. These pressures only divided ASEAN further as the region looks ahead to a trifecta of international meetings—APEC, East Asia Summit, and the G20—in the fall.

Political activity was also at high levels, with elections in the Philippines; a surprise move by the Constitutional Court of Thailand to suspend Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha; and a prison sentence for former Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak. In Thailand, Cambodia, Malaysia, Indonesia and possibly Myanmar, current political dynamics will help set the stage for elections in 2023 and 2024.

US - Southeast Asia

January — April 2022Regional Powers Cast Long Shadows: ASEAN Grapples with New Dynamics

In the early months of 2022 the Russian invasion of Ukraine had a major, if indirect, impact on Southeast Asia and its relations with the major powers. Rising commodity prices and added disruptions in global supply chains caused by the invasion threatened to erase economic gains following the damage of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021. ASEAN splintered in its response to the invasion, putting further strain on an institution already buckling under the worsening conflict in Myanmar. A year past the coup in Naypyidaw, the ASEAN Five-Point Consensus Plan has barely moved forward. Beijing’s apparent, if cautious, support for Moscow following the invasion added new tensions in a region already on edge with growing Chinese assertiveness and a reinvigoration of US alliances. Chairing the G20 for the first time this year, Indonesia faces demands from the West to expel Russia from the group, a proposal that China vigorously opposes. The Ukraine conflict exacerbates ASEAN’s fear of being caught between the West and China, but adds a new concern that the Asia-Pacific region might further nuclearize with the threat of a nuclear standoff between Russia and NATO.

US relations with Southeast Asia began the year on a positive note following the stream of visits from high-level officials from the Biden administration in the second half of 2021. By late March, however, the US-ASEAN Special Summit had been postponed, in part because of ASEAN uneasiness over Washington’s intense focus on Ukraine. The campaign for Philippine elections was launched officially in February, and Ferdinand “Bong Bong” Marcos, son of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos, maintained a steady lead and realized a substantial win in the presidential race on May 9, with Sara Duterte as his vice president. Politics in both Malaysia and Thailand were less straightforward, but by the end of April both countries appeared to be heading for early elections. A political transition of a different sort took place in Singapore, when President Lee Hsien-Loong named Finance Minister Edward Wong as the new leader of the People’s Action Party, effectively making Wong his political heir and the next prime minister.

US - Southeast Asia

September — December 2021Myanmar Spirals Downward While ASEAN Drifts

ASEAN unity wobbled in the final months of 2021, largely over the worsening conflict in Myanmar and the group’s inability to advance the five-point consensus plan it had forged in April. Vaccination rates for COVID-19 picked up, but governments that had hoped to return to pre-pandemic economic growth rates worried that the omicron variant would undo progress that had been made. Political challenges were no less daunting in several countries. The nomination process for May 2022 presidential elections in the Philippines showed that political dynasties are strengthening and may even merge. In Malaysia, the success of the United Malay Organization (UMNO) in state elections raised the prospect that the party will recover some of its former strength, although not its political monopoly. Anti-government demonstrations in Thailand became more perilous for protestors in November when the Constitutional Court ruled that advocating reform of the monarchy, one of the central planks of the protest movement, was tantamount to treason.

The region was also pressed to respond to great power dynamics, most notably to the announcement in September of the Australia/United Kingdom/United States (AUKUS) alliance and to China’s bid to elevate its relations with ASEAN to a comprehensive strategic partnership. At the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue Summit. the four nations opened a window to address nontraditional security threats, which could pull the ASEAN countries closer to the Quad. The Biden administration stepped up diplomacy with ASEAN with a virtual US-ASEAN Summit on the margins of the East Asia Summit in October and Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s first trip to Southeast Asia in his capacity as secretary. Although Southeast Asian leaders welcomed the attention, they are increasingly impatient for Washington to define its economic plans with the region.

US - Southeast Asia

May — August 2021Washington Finds Its Feet in Southeast Asia

In the months immediately following Joe Biden’s inauguration, Southeast Asia was on the backburner in US foreign policy, but in May the administration heeded calls for a stronger voice and more active role in the region with a succession of visits by high-level officials, culminating in Kamala Harris’s first trip to the region in her role as vice president. The cumulative impact remains to be seen, but one key “deliverable”—the renewal of the US-Philippines Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA) during Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin’s visit to Manila—was enough to label the summer strategy a success. More broadly, the administration responded to the surge of the COVID Delta variant in Southeast Asia with donations of vaccines, making considerable strides in the “vaccine race” with China and Russia.

US - Southeast Asia

January — April 2021ASEAN Confronts Dual Crises

The Feb. 1 coup in Myanmar dealt a serious blow to the ASEAN diplomatic order and presented the incoming Biden administration with its first major policy challenge in Southeast Asia. More profoundly, the coup set into motion a political and humanitarian crisis that has pushed Myanmar into an economic free fall. The imposition of Western sanctions gave China and Russia an opening to strengthen ties with the Tatmadaw. Myanmar was an extreme example of political turmoil, but the instability surrounding Thailand’s anti-regime and anti-monarchy movement persisted into the new year. In January, Vietnam embarked upon a more orderly political transition through the 13th National Party Congress, resulting in a leadership structure focused on ensuring stability, both external and internal.

US - Southeast Asia

September — December 2020Waiting on Washington: Hopes for a Post-Election Boost in Us Relations

The resurgent COVID-19 pandemic and US elections constrained the conduct of US relations with Southeast Asia and of regional affairs more broadly in the final months of 2020. Major conclaves were again “virtual,” including the ASEAN Regional Forum, the East Asia Summit. and the APEC meeting. Over the year, ASEAN lost considerable momentum because of the pandemic, but managed to oversee completion of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in November. Some modest gains in US-Southeast Asian relations were realized, most notably extension of the US-Philippines Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA) for another six months, an opportunity for Manila and the new administration in Washington to put the VFA—and the US-Philippines alliance more broadly—on firmer ground. Another significant step, albeit a more controversial one, was the under-the-radar visit to Washington of Indonesian Defense Minister, Prabowo Subianto, in October.

US - Southeast Asia

May — August 2020Diplomatic Doldrums: ASEAN Loses Momentum in the Pandemic as Security Tensions Rise

As Southeast Asia struggles to gain traction in the COVID-19 pandemic and address the economic damage it has imposed, leaders are hobbled by travel restrictions and other conditions that make forging a regional approach to the virus more difficult. Although most states have launched partial and cautious reopening strategies, most intergovernmental business is still conducted online. This will remain the case for the rest of 2020, given widespread fears of a second surge of the coronavirus. In the meantime, several leaders face political challenges as their domestic populations struggle under the worst recession in years. Diplomatic traffic is ordinarily busy in the summer in Southeast Asia, but this year the Shangri-la Dialogue in Singapore was cancelled, the ASEAN Summit forced to go online, and the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) pushed into the early fall, also to be conducted by video. Security tensions were not held in abeyance by COVID, and may have been exacerbated by it. China’s attempts to disrupt oil and gas explorations of the Southeast Asian claimants in the South China Sea evoked an unusually strong statement from Washington in mid-July; the reactions of the Southeast Asian claimants, particularly Vietnam and the Philippines, were a litmus test in part of their confidence in the US to ameliorate the situation. A security crisis of a different sort continued as the Mekong River entered its second year of drought, raising concerns about upstream dams controlled by China.

US - Southeast Asia

January — April 2020Fighting the Pandemic, ASEAN Braces for Economic Pain

Many Southeast Asian countries’ growth rates have been stripped to near zero by COVID-19, and leaders expect a crisis that could exceed that of the Asian Financial Crisis. The pandemic defined Southeast Asia’s diplomatic relations from March, with high-level meetings moved to video conferences. The US-ASEAN summit, scheduled for March 24, was postponed but no new date has been announced. With US elections ramping up and questions about the COVID-19 pandemic outstanding, a 2020 US-ASEAN summit appears unlikely.

US - Southeast Asia

September — December 2019Engagement in Absentia? ASEAN Worries over Lack of US Attention

Stung by a US delegation to the East Asia Summit of lower rank than previous years, ASEAN leaders retaliated by presenting National Security Advisor Robert O’Brien with a partial boycott of the adjacent US-ASEAN Summit. The Trump administration brushed off the incident with a State Department fact sheet that began, “US engagement with the ten member states of ASEAN has never been stronger.”

US - Southeast Asia

May — August 2019ASEAN Centrality Under Siege

Two regional meetings in Southeast Asia over the summer – the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore and the ASEAN Regional Forum in Bangkok – revealed growing angst among Southeast Asian leaders over narrowing political space in which to balance relations in the context of US-China competition. More broadly, the relevance of ASEAN in these polarizing times has come into question and subregional arrangements, such as the Ayeyawady-Chaopraya-Mekong Economic Cooperation Strategy (ACMECS) are emerging. Recent incidents point to growing Chinese assertiveness in the South China Sea. A reported agreement with Cambodia to build a strategic outpost on the Gulf of Thailand has drawn sharp criticism from Washington. But it is unclear how able or willing Southeast Asian governments are to push back since they view China as a critical economic partner. As several Southeast Asian leaders contemplate retirement, economic security is a common element in the legacies they envision.

US - Southeast Asia

January — April 2019Strategic Concern Deepens

The choice of two Southeast Asian countries to host US-North Korea summits in the past year has lent some credence to claims that the region serves as the foundation for regional dialogue and cooperation. In early 2019, the region was also the recipient of extra attention when foreign investment in China began to move south, driven by US tariffs on China imposed in late 2018. However, there was little sign that new bilateral trade agreements with the US will materialize in the near term. Meanwhile, greater security cooperation with the US is more likely with the bombing of a cathedral in the southern Philippines in January serving as another harbinger of increased ISIS activity in the region and continued militarization of the South China Sea strengthening the rationale for the US-Philippines alliance but also putting more pressure on it. In political developments, Thai elections in March left questions about whether the military will remain dominant while Indonesian elections in April were less controversial, with incumbent President Joko Widodo retaining power.

US - Southeast Asia

September — December 2018Deepening Uncertainties

At the mid-point in the tenure of President Donald Trump, Southeast Asian leaders have largely accepted that the era of special attention to the region, which began in the second term of George W. Bush and continued through the Obama administration, has largely passed, if only temporarily. To be sure, Southeast Asia is included in the Indo-Pacific framework and will figure to some extent in Washington’s plans to counter China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which will be partially implemented through the Better Utilization of Investment Leading to Development (BUILD) Act. The region continues to hold up one side of the conflict with China over sovereignty and island-building in the South China Sea and so can be assured of continued attention from the US Indo-Pacific Command. Apart from these broad issues and initiatives, US-Southeast Asian dynamics have returned to a status quo ante of the 1990s, when Washington was focused on geopolitical shifts in other regions, and relations with Southeast Asian nations were bilateral and spiky.

US - Southeast Asia

May — August 2018Caught in the Crossroads of Major Power Tensions

Southeast Asian governments have warmed to the Indo-Pacific concept being promoted by the US, which reinforces their own inclination to expand the cast of regional powers to balance China’s rise. However, they are still wary that a disorganized Trump administration will not be able to translate its rhetoric into policies. In the meantime, they fear being caught between Washington and its Northeast Asian adversaries. Apart from possible clashes between regional powers, Southeast Asia itself offers a number of challenges to smooth relations with the US. Recent elections in Malaysia and Cambodia are two of them, albeit for different reasons. In Indonesia, candidates have been declared for the 2019 presidential elections that could feed growing religious nationalism and anti-Americanism. The Rohingya refugee crisis has ratcheted up tensions between the West and Myanmar over the impact of the 2017 crackdown.

US - Southeast Asia

January — April 2018Policy on Auto-Pilot

The difficulties of the Trump administration in forging a coherent foreign policy were on display in US relations with Southeast Asia in the early months of 2018. The Department of Defense played an outsized role as both Secretary of Defense James Mattis and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Joseph Dunford made visits to the region. The customary menu of multilateral and bilateral exercises with Southeast Asian militaries, including the 37th round of the annual Cobra Gold exercises, reassured security partners of continued defense cooperation. However, piecemeal diplomatic activity by the US underscored perceptions that the Trump administration has downplayed the region’s significance, exacerbated by heightened rhetoric about the still-undefined “free and open Indo-Pacific region.” Chinese assertiveness in the South China Sea and the Rohingya refugee crisis continued to be of mutual concern, but were overshadowed by the emerging dialogue on the Korean Peninsula and growing trade tensions between China and the US, leaving Southeast Asian governments in a reactive mode.

US - Southeast Asia

September — December 2017Abandoning Leadership

Concerned about what Southeast Asian leaders see as US neo-isolationism under President Donald Trump, the heads of government from Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, and Singapore all visited Washington in the last four months of 2017. Trump’s trip to Asia in November led to additional talks with Vietnam’s leaders and Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte. These activities could be termed “shopping diplomacy” in that each leader has sought to curry favor with the United States and all announced plans to purchase more US goods and invest in US companies to help Washington reduce its balance of payments deficit. They also emphasized that their economic infusions in the US would generate thousands of new US jobs. Politically, their combined message was that the US should not leave Southeast Asia to China’s tender mercies but that Washington should remain a major actor in the region’s security, economic activities, and political organizations.

US - Southeast Asia

May — August 2017Regional Skepticism

Unlike its predecessor, the Trump administration has not devoted much attention to Southeast Asia; there is no clear policy toward the region. Instead, two areas have been emphasized: an increase in the number of Navy ship-days in the South China Sea and regular economic pressure on Southeast Asian states based on the president’s “America First” principle. Insofar as there is a security policy, it has been to gain support for Washington’s efforts to isolate North Korea. US relations with the Philippines have improved because there have been limited complaints about President Duterte’s war on drugs and increased support for the Philippine Armed Forces’ counterterrorism actions in Mindanao. Vietnam Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc’s trip to Washington focused on reducing Hanoi’s trade surplus, and, in August, Secretary of Defense Mattis promised a visit by a US aircraft carrier to Vietnam, the first since the end of the Vietnam War. Washington applauded the ASEAN-China agreement on a framework for a code of conduct for the South China Sea, urging that the actual code be legally binding, a stipulation opposed by China.

US - Southeast Asia

January — April 2017Mixed Messages

In its early months, the Trump administration has devoted little attention to Southeast Asia and US relations with the region have generally followed a trajectory set by the Obama administration. The US continued naval operations in the South China Sea and joint exercises with most ASEAN states with US air and naval forces rotating through bases in northern Australia and the Philippines and deploying from Singapore. There have been mixed signals between Manila and Washington. With the ASEAN states and China moving toward completion of a Code of Conduct (COC) on rules of engagement in the South China Sea, it is hoped that the new document would be “legally binding,” but little specific about its provisions has been published. Following Washington’s abrogation of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), Hanoi has sought to alleviate its disappointment, saying that it understands the US need to create more jobs and that it will try to accommodate Washington in future trade negotiations.

During the Obama administration’s two terms (2009-2016), the president’s “rebalance” to Asia featured Southeast Asia as its centerpiece. President Obama made 11 separate trips to the Asia-Pacific, visiting a total of 14 countries, nine of which were members of ASEAN. His secretaries of state and defense also made multiple journeys to the region. Among many successes during these years were US accession to ASEAN’s Treaty of Amity and Cooperation, participation in the East Asia Summit for the first time in 2011, the establishment of the first diplomatic mission to ASEAN, and realization of the historic transition to democracy in Myanmar. The United States also increased the deployment of ships and aircraft to the region, particularly in Singapore, the Philippines, and Australia. In Obama’s final year, the US began distributing resources under the Maritime Security Initiative to assist Southeast Asian countries with their maritime domain awareness by transferring patrol vessels and surveillance aircraft as well as creating a system whereby these countries could share information on the region’s maritime security picture.

While it’s still early for the Trump administration, there have been virtually no policy statements dealing with Southeast Asia, nor at this time (April) has the State Department chosen a deputy secretary – the number two position – or a permanent assistant secretary for East Asian and Pacific affairs. Direction from Washington for a region that was so important during the preceding eight years seems to be absent.

US - Southeast Asia

September — December 2016Philippine Follies

The rather bizarre behavior of Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte dominated the news in late 2016. The former Davao mayor displayed his well-known anti-US feelings while aggressively pursuing his allegedly extrajudicial campaign against Philippine drug trafficking. Duterte’s invective ran the gamut from accusations that the US still treated the Philippines as a colony to a vulgar epithet directed at President Obama. There were also threats to end all bilateral military exercises and to terminate bilateral defense agreements. Philippine officials tried to soften Duterte’s remarks and US officials offered reassurances that the US would remain a reliable defense partner and planned to continue providing military assistance. Elsewhere, the US continued to focus attention on maritime security while avoiding direct involvement in the emerging controversy over treatment of the Muslim population in Rakine State, Myanmar.

US - Southeast Asia

May — August 2016Augmented Presence

The Obama administration has achieved only a portion of its Asian rebalance strategy in Southeast Asia. Washington is repositioning elements of the US Navy to the Pacific, engaging in “freedom of navigation patrols,” and providing assistance to Vietnam and the Philippines to monitor and defend their maritime territories. US leaders are regularly attending ASEAN-based meetings to demonstrate US commitment to Asia. President Obama regularly promotes the Tran-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Despite these advances, US presidential electoral politics are presenting new obstacles. Meanwhile, the US has urged caution with respect to the UNCLOS Arbitral Tribunal’s decision on the South China Sea. Human rights concerns continue to trouble US relations with Hanoi as well as Bangkok, Nay Pyi Taw, Vientiane, and Phnom Penh.

US - Southeast Asia

January — April 2016ASEAN Centrality?

The mid-February ASEAN-US Summit was the Obama administration’s effort to show ASEAN’s central role in the US rebalance to Asia. It was only partially successful. Several new business initiatives were inaugurated to link US and ASEAN entrepreneurs. However, security cooperation hardly advanced. While maritime security was included in the joint declaration, there was no mention of US freedom of navigation (FON) patrols or the South China Sea disputes. In January, the Philippine Supreme Court cleared the way for the Philippine-US Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement, allowing US forces rotational access to several Philippine military bases and enhancing interoperability. Washington plans to increase the frequency and “complexity” of FON patrols near the artificial islands built by China, and the US has begun joint patrols with Philippine ships. Washington also announced a Southeast Asian Maritime Security Initiative that includes a $425 million multi-year appropriation for regional capacity to improve maritime domain awareness and patrols.

US - Southeast Asia

September — December 2015Commitment Concerns

US relations with Southeast Asia encompassed all three pillars of its rebalance to Asia: military presence, multilateral diplomacy, and economic engagement. Militarily, the freedom of navigation voyage of the USS Lassen past China’s artificial islands occurred while the Department of Defense announced a $425 million five-year military aid program for Southeast Asian states and the White House committed an additional $259 million in military support for Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines. Diplomatic engagements included visits to the region by the president, the secretaries of state and defense, and a number of senior aides to attend multilateral meetings. Commitment to the economic pillar led to the conclusion of negotiations for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement. If ratified by the signatories, the TPP would be the most comprehensive trade and investment arrangement in the world, though a number of obstacles in many of the countries do not portend a quick or easy confirmation.

US - Southeast Asia

May — August 2015Courting Partners

Senior State and Defense Department officials made several visits to Southeast Asia over the summer months, assuring their hosts that the US remained committed to a robust air and naval presence in the region, and assisting the littoral countries of the South China Sea in developing maritime security capacity. Washington is particularly focused on providing a rotational military force presence in Southeast Asia. On the South China Sea territorial disputes, US officials emphasized the need for peaceful approaches to conflict settlement among the claimants, pointing to arbitration and negotiation based on the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. Washington has also accentuated the importance of security partners for burden-sharing, noting the potential for an enhanced role for Japan’s Maritime Self-Defense Force in South China Sea patrols. Efforts to involve Southeast Asian states in negotiating the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) have elicited candidates from only four of the 10 ASEAN states – Malaysia, Vietnam, Singapore, and Brunei. Others have problems meeting several requirements associated with the partnership.

US - Southeast Asia

January — April 2015South China Sea Wariness

In the first four months of 2015, senior State and Defense Department officials as well as flag-rank military officers visited Southeast Asia, all emphasizing ASEAN’s importance for the Obama administration’s rebalance policy. The US is building a rotational force deployment capacity in the region along with military assistance to allies and partners, especially for increasing their maritime security capabilities. Washington and Manila await a Supreme Court decision regarding the constitutionality of the April 2014 Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA), which will permit better access for US forces. Washington has also emphasized Vietnam’s importance to the rebalance, currently concentrating on improving coast guard relations. However, the US was dismayed that Hanoi permitted Russian tanker aircraft to fly out of Cam Ranh Bay to refuel bombers that flew near US bases in Guam. The Indonesian Navy has shown interest in more naval exercises with the US around the Natuna Islands. Problems persist in US-Thai relations as the military consolidates its rule. Although the annual Cobra Gold exercise took place in February, Washington scaled back US participation and significantly reduced the kinetic component. Planning for next year’s exercise is in limbo. Finally, Japan and India have shown support for maritime security buildups and an enhanced naval presence in the South China Sea.

US - Southeast Asia

September — December 2014Diplomatic Gambits

Senior US officials at ASEAN-based meetings touted the Association’s centrality for the Obama administration’s rebalance to Asia. Nevertheless, a US proposal at the East Asia Summit (EAS) in November that all South China Sea claimants “freeze” efforts to alter the status quo on the islets they control was not endorsed. In the Philippines, there was some progress on implementing the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement, though opponents have challenged its constitutionality. The US partially lifted its arms embargo with Vietnam, agreed to resume Cobra Gold in Thailand in 2015, and expressed approval of Indonesia’s ambitious maritime development program. Human rights concerns were noted by US officials in response to ongoing ethnic tensions in Burma and the Najib government’s decision to repeal the 1948 Sedition Act in Malaysia.

US - Southeast Asia

May — August 2014Enhancing the Rebalance

Senior US officials emphasized the centrality of Southeast Asia in the Obama administration’s rebalance policy at several ASEAN-based venues, where they stressed the roles of these organizations in regional diplomacy for resolving disagreements. At the ARF, Secretary of State Kerry proposed a freeze by South China Sea claimants on activities that would unilaterally change the status quo, which the ASEAN states generally supported. The US is negotiating the implementation of the Expanded Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) with the Philippines and there was also talk of a more extensive security relationship with Vietnam. For some time Hanoi has sought more US intelligence on the South China Sea and Washington would like more access for Seventh Fleet ships to Vietnamese ports. There were also suggestions that the US is reconsidering its ban on weapons sales to Hanoi.

US - Southeast Asia

January — April 2014A Strong Start to the New Year

The US raised its profile in Southeast Asia with a series of high-profile visits and events in early 2014. Secretary of State John Kerry visited Indonesia, delivering a speech on climate change, and Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel hosted a US-ASEAN Defense Ministers Meeting in Hawaii. President Obama visited Malaysia and the Philippines, stops he had cancelled last fall because of the US government shutdown. The trip shored up the administration’s assertion that the US “rebalancing” to Asia is real and that Southeast Asia is critical to that process. However, the heavy emphasis on defense in Obama’s Philippines visit also reinforced Southeast Asian perceptions that the “pivot” is primarily a security policy. Broad movement on the Trans-Pacific Partnership was held hostage to disagreements between the United States and Japan. Relations between Washington and Nay Pyi Taw are slowing over continued violence in Rakhine State.

US - Southeast Asia

September — December 2013Obama Passes

Faced with a government shutdown and a debt default crisis, President Obama canceled an extended visit to Southeast Asia. While Secretary of State Kerry filled in for the president at these venues and most regional leaders expressed understanding, several also expressed anxiety over Washington’s ability to carry out a consistent policy toward Southeast Asia. The US rebalance toward Asia continued with financial commitments to enhancing maritime security, announcements of military sales, deployment of an additional Littoral Combat Ship to Singapore, and calls for accelerated negotiations on the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement. The robust response by the US to Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines was widely viewed as a concrete example of the ongoing US security commitment to its allies and partners.

US - Southeast Asia

May — August 2013Philippines – an Exemplar of US Rebalance

The Philippines has linked its military modernization and overall external defense to the US rebalance. Washington has raised its annual military assistance by two-thirds to $50 million and is providing surplus military equipment. To further cement the relationship, Philippine and US defense officials announced that the two countries would negotiate a new “framework agreement” under the 1951 Mutual Defense Treaty providing for greater access by US forces to Philippine bases. Washington is also stepping up participation in ASEAN-based security organizations, sending forces in June to an 18-nation exercise in Brunei. A visit to Washington by Vietnam’s President Truong Tan Sang resulted in a US-Vietnam Comprehensive Partnership. Myanmar’s president also came to Washington, the first visit by the country’s head of state since 1966. An economic agreement was the chief deliverable. While President Obama praised Myanmar’s democratic progress, he also expressed concern about increased sectarian violence.

US - Southeast Asia

January — April 2013Military Commitments and Human Rights Concerns

In emphasizing the Southeast Asian component of the US rebalance to Asia, US officials noted the “whole of government” approach that involves economics, strengthening regional institutions, and expanding partnerships. Moreover, much of the motivation for the rebalance, according to these officials, comes from Southeast Asians pressing for US leadership. In the realm of defense, the US emphasizes assisting partners to improve their own capabilities and working within security-related institutions such as the East Asia Summit – the premier forum for political-security issues in Asia. Washington is supporting security improvements in a number of countries in the region, including the Philippines, Thailand, Singapore, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Malaysia. Alongside these growing partnerships, however, are US criticisms of human rights problems in the Indochinese countries, Burma, and Indonesia that add friction to the relationships.

US - Southeast Asia

September — December 2012High-Level Attention

The importance of Southeast Asia in the US “rebalance” to Asia was underscored by President Obama’s visit to Thailand, Burma (Myanmar), and Cambodia in November, covering both bilateral relations and the region’s centrality in Asian multilateralism. Secretaries Clinton and Panetta also spent time in the region, the latter reinvigorating defense ties with Thailand and linking US security interests among Australia, India, and Southeast Asia. While visiting Jakarta in September, Clinton reinforced US support for the ASEAN plan to negotiate a formal South China Sea code of conduct, endorsing the six-point principles Indonesian Foreign Minister Marty Natalegawa negotiated after the failed ASEAN Ministerial Meeting in July. At the East Asia Summit, the majority of ASEAN states, Japan, and the US insisted that the South China Sea appear on the agenda despite objections from Cambodia and China. Obama’s visit to Myanmar occasioned the declaration of a “US-Burma partnership,” though the visit was marred by violence against the Rohingya population in Rakhine (Arakan) state. Washington is also enhancing military ties with the Philippines, Thailand, and Indonesia as part of the “rebalance.”

US - Southeast Asia

May — August 2012ASEAN Stumbles

Indonesian efforts to salvage ASEAN unity after the failure to issue a formal communiqué at the end of its 45th Ministerial Meeting were successful. Stymied by a lack of consensus over the inclusion of Philippine and Vietnamese complaints about Chinese maritime confrontations in the South China Sea (SCS) in the communiqué, Indonesia’s foreign minister presented a minimal SCS code of conduct statement that ASEAN members subsequently accepted. At the US-ASEAN Post-Ministerial Conference, Secretary of State Clinton reiterated US support for a peaceful negotiated settlement to SCS disputes and emphasized the importance of ASEAN-based institutions in the resolution process. Linking enhanced US military aid for the Philippines to President Aquino’s 2013-2017 navy and air force development plan, Washington hopes to help Manila improve its “maritime domain awareness.” The US also announced during Defense Secretary Panetta’s visit to Cam Ranh Bay that it would be adding naval visits to Vietnam. The US suspended many prohibitions against private investment in Myanmar, though human rights-based sanctions remain. At the Shangri-La Dialogue, Panetta outlined an ambitious plan for enhanced military partnerships with regional friends and allies, though how a reduced US military budget will impact these plans is a growing concern in Southeast Asia.

US - Southeast Asia

January — April 2012Conflict in the East; Opportunity in the West

US attention was focused on both ends of Southeast Asia: in the east on tensions in the South China Sea between China and the Philippines, which have energized the US-Philippine alliance; and in the west on the impact of April by-elections in Burma, which have paved the way for a quantum leap in US engagement with the country. Attacks and explosions in Thailand and the Philippines were a reminder that terrorism is still a serious threat. Policy debate over the US “pivot” to Asia was stimulated by a US request to double the number of littoral combat ships to be docked at Singapore as well as by discussion on the rotation of US troops through Philippine bases. Both represent modest steps toward “flexible bases” in Southeast Asia. The unprecedented number of US joint exercises and other forms of military cooperation anticipated in 2012 suggest the “pivot” is an ongoing and incremental process that has been underway for years.

US - Southeast Asia

September — December 2011Rebalancing

With visits to Hawaii, Indonesia, Australia, the Philippines, and Burma, President Obama and Secretaries Clinton and Panetta demonstrated a renewed US commitment to Southeast Asia despite concern over a projected steep decline in the US defense budget. Southeast Asian reactions to the announcement of an increased rotation of US military assets to Australia range from ambivalence in Indonesia to enthusiastic endorsement in the Philippines and Singapore. Generally, the additional US forces are seen as evidence of Washington’s decision to remain involved in regional security. At the East Asia Summit (EAS), Obama outlined his hope that it could serve as a high-level security conclave whose agreements would be implemented through other multilateral organizations. In visits to the Philippines and Indonesia, Clinton and Obama promised naval and air force upgrades to each, including two squadrons (24 aircraft) of refurbished F-16C/Ds for Jakarta. Hoping for a breakthrough in US-Burma relations, Obama sent Clinton to see whether the situation warranted the easing of US economic sanctions and if Naypyidaw was moving to meet US conditions for the restoration of full diplomatic relations.

US - Southeast Asia

May — August 2011Deep in South China Sea Diplomacy

Diplomacy related to the South China Sea disputes dominated US actions at the May ASEAN Summit, the June Shangri-La Dialogue, and the July ARF meeting. Washington endorsed ASEAN consultations before the Association’s meetings with China on the territorial disputes as well as an independent ASEAN role in the South China Sea negotiations separate from the bilateral negotiations preferred by the PRC. Related to US support for ASEAN is Washington’s assistance to the Philippines in gradually building its archipelagic security capability by funding Coast Watch South radars and promising more military hardware to the ill-equipped and underfunded Philippine armed forces. Manila also maintained its efforts to obtain a specific defense commitment from the US in the event of a military conflict with China over South China Sea islands. The Cambodia-Thai border dispute continues to flare periodically. ASEAN mediation efforts have established a timetable for military disengagement but, as yet, no implementation. Washington has endorsed the ASEAN efforts. In Indonesia, radical Jemaah Islamiyah, al Qaeda-affiliated cleric Abu Bakar Bashir was sentenced to 15 years in jail for aiding the formation of a new terrorist affiliate in Aceh. As in his previous trials, Bashir blamed his arrest and sentence on US and Jewish machinations. Although the Obama administration has appointed a new envoy, Derek Mitchell, as special ambassador to coordinate international approaches to Burma, this enhanced engagement runs parallel to increased US economic sanctions, suggesting little has changed with the new “civilianized” government.

US - Southeast Asia

January — April 2011Dismay at Thai-Cambodia Skirmishes

Both the US and ASEAN expressed dismay at border skirmishes between Thailand and Cambodia around the Preah Vihear temple and two other ancient temples about 160 km to the west. Artillery exchanges and small arms fire call into question the two countries’ commitment to the ASEAN rule of the peaceful settlement of disputes among its members. Washington has promised to aid Philippine maritime capabilities to patrol both its South China and Sulu Seas’ territorial waters as part of a larger US goal of keeping Asian sea lanes open. New ships and radar installations as well as navy and coast guard training are being provided by the US. In Indonesia, the US embassy inaugurated a new public diplomacy program, @america, an interactive information technology site designed to demonstrate the breadth of American life to Indonesia’s tech-savvy young people. Wikileaks releases of US embassy cables published in the Australian press critical of President Yudhoyono caused some tension between Jakarta and Washington. As the current ASEAN chair, Indonesia seemed to follow Secretary of State Clinton’s call for an ASEAN role in resolving the South China Sea islands dispute. US relations with Vietnam and Cambodia continue to be strained over human rights concerns. While ASEAN has called for the lifting of economic sanctions on Burma since its recent national election and the release of Aung San Suu Kyi from house arrest, Washington seems in no hurry to follow suit, labeling the election as fatally flawed and noting that political prisoners remain in jail. Finally, the US promised high-level participation in ASEAN-led regional organizations, including the ARF, the ADMM+, APEC, and the EAS.

US - Southeast Asia

October — December 2010Full Court Press

High-level visits to Southeast Asia this quarter found President Obama in Indonesia to inaugurate a Comprehensive Partnership, Secretary of Defense Gates in Malaysia and Vietnam, and Secretary of State Clinton in several Southeast Asian states, a trip that was highlighted by her acceptance of US membership in the East Asian Summit and attendance at the Lower Mekong Initiative meeting. Obama praised Jakarta’s democratic politics and insisted that the multifaceted relations with Jakarta demonstrate that Washington is concerned with much more than counterterrorism in its relations with the Muslim world. In Vietnam, both Clinton and Gates reiterated the US position from the July ASEAN Regional Forum that the South China Sea disputes be resolved peacefully through multilateral diplomacy led by ASEAN. Clinton expressed Washington’s appreciation that China had entered discussions with ASEAN on formalizing a Code of Conduct on the South China Sea. In all her Southeast Asian stops, she emphasized the importance of human rights. While deploring the faulty election in Burma, the US welcomed Aung San Suu Kyi’s release from house arrest and the prospect for more openness in Burmese politics.

US - Southeast Asia

July — September 2010Growing Enmeshment in Regional Affairs

The United States significantly raised its political profile in Southeast Asia this quarter, inserting itself in South China Sea disputes, announcing its plan to join the East Asia Summit, convening the second US-ASEAN summit, and creating an ambitious agenda for participation in a variety of Southeast Asia programs. On the South China Sea issue, Secretary of State Clinton proposed multilateral discussions under ASEAN auspices – an idea that did not appear, however, in the ASEAN-US summit communiqué in late September. The US inaugurated naval exercises with Vietnam in early August, coinciding with the visit of the aircraft carrier USS George Washington. Washington is considering new financial sanctions against Burma, recognizing that more engagement with the military regime has not yielded the expected results. The presence of US military trainers in the southern Philippines continues to rile leftist and nationalist legislators. As a sign of growing warmth in US-Malaysian relations, Kuala Lumpur is sending a small contingent of medical personnel to Afghanistan. The Indonesian-US Comprehensive Partnership was launched in Washington in September, signifying Jakarta’s special importance to the US. Washington also restored military-to-military relations with Kopassus, the Indonesian Special Forces unit that has been accused of egregious human rights violations in Timor, Papua, and Aceh.

US - Southeast Asia

April — June 2010Thai Turmoil; President Postpones Indonesia Trip Again

In mid-May, long-simmering political tension in Thailand between the Bangkok elite establishment and urban lower classes as well as those in northern Thailand who feel ignored by the center erupted in the worst political violence in decades. Tentative US efforts to mediate were rejected by the Thai government, though the opposition appeared to welcome a US role. A tense calm has been restored, but the prospect for renewed violence is palpable. While the Indonesian government expressed understanding for President Obama’s second postponement of a visit to his childhood home because of the disaster in the Gulf of Mexico, opposition Muslim politicians claimed the real reason for the postponement was the Israeli attack on a Turkish flotilla running Israel’s Gaza blockade. A number of Muslim leaders stated that Obama wished to avoid encountering Indonesian ire for his country’s pro-Israeli stand. The election of Benigno Aquino III as the Philippines’ 15th president was greeted by international observers as a generally fair and transparent process. The president-elect has stated he plans to review the country’s Visiting Forces Agreement with the US to modify its pro-US bias. Washington continues to criticize Burma’s preparations for elections scheduled for October as marginalizing the political opposition. The US is also concerned that Burma may be clandestinely importing materials from North Korea for a nascent nuclear weapons program.

US - Southeast Asia

January — March 2010Denouement and Delay

After banner initiatives in US policy toward Southeast Asia were unveiled in 2009 – the US-ASEAN Leaders Meeting, signing the ASEAN Treaty of Amity and Cooperation, and a 45-degree change in Burma policy that added engagement to sanctions – a loss of momentum in early 2010 was hardly surprising. President Obama’s decision to delay his long-awaited trip to Indonesia twice in March added to the impression of a slump in relations with the region. The administration proved to be prescient in its warning last fall that greater engagement with the Burmese regime would not likely reap short-term gains when the junta announced restrictive election laws. However, in the first quarter of 2010 the US also moved forward on two regional initiatives – strengthening its interest in the TransPacific Trade Partnership, which could be a route to trade liberalization with several Southeast Asian countries, and preparing to establish a Permanent Mission to ASEAN. Despite Bangkok’s ongoing political crisis and a new wave of “red shirt” protests, the US and Thailand implemented new rounds of two multilateral military exercises in this quarter, including the flagship Cobra Gold. At the end of the quarter the US and Vietnam signed a landmark Memorandum of Understanding on the development of civilian nuclear power facilities, a bilateral segue to the multilateral nuclear summit that Obama will host with 43 heads of state in mid-April.

US - Southeast Asia

October — December 2009Engagement with Burma Ramps Up

High-level US efforts to convince Burma’s military government to open its political system to the democratic opposition and release political prisoners prior to scheduled 2010 elections accelerated this quarter. President Obama, Secretary of State Clinton, and Assistant Secretary of State Campbell all weighed in during meetings in Burma and at the first ASEAN-US summit in Singapore after the annual APEC leaders meeting. The ASEAN states welcomed the first US summit with all 10 members. Secretary General Surin Pitsuwan noted that President Obama’s praise for ASEAN’s key role in Asian international organizations debunked claims by some that ASEAN is no longer the centerpiece of the region’s architecture. Singapore’s prime minister insisted that the US continues to be Asia’s “indispensable” player despite the rise of China and India. In the Philippines, the Visiting Forces Agreement continues to be a political football in domestic Philippine politics as President Arroyo’s political opponents claim that the US military violates the Philippine constitution by engaging in combat – an allegation denied by both the US embassy and the Philippine government. On a tip from the US, Thai authorities detained a cargo aircraft coming from North Korea with a load of sophisticated weapons in violation of a UN Security Council Resolution.

US - Southeast Asia

July — September 2009The United States Is Back!

Despite the renewed incarceration of Burma’s Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi after a July “show trial” as well as renewed economic sanctions against the military junta, in late September Washington announced a change in its Burma policy, agreeing to reengage members of the regime. The opening to Burma is an acknowledgement that the decades-long isolation policy has failed to change Burma’s politics and that China’s influence has increased significantly. Defense Secretary Robert Gates announced an extension of the deployment of U.S. Special Forces in Mindanao to continue assisting the Philippine armed forces’ suppression of the radical Islamist Abu Sayyaf. Gates also announced an expansion of U.S. aid in Mindanao for humanitarian and disaster response, climate change, drug trafficking, and maritime security. While expressing shock and offering condolences to Indonesia in the wake of the July terrorist bombings of two hotels in Jakarta, Washington praised the Indonesian police in mid-September for tracking down and killing the perpetrator of the attacks, notorious Jemmah Islamiyah leader, Mohammad Noordin Top. USAID is organizing a new program to assist civic social organizations in the troubled Thai south to promote governance and human rights. All of these activities indicate that, as Secretary of State Clinton exclaimed in Bangkok: “The United States is back!”

US - Southeast Asia

April — June 2009President’s Cairo Speech Resonates in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia media and elites praised President Barack Obama’s Cairo address for opening a new dialogue with Muslims and acknowledging U.S. transgressions after 9/11. Washington excoriated Burma’s ruling junta for transferring opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi to prison for violating the regime’s detention law, characterizing the charges as ”baseless” and an excuse to extend her incarceration beyond scheduled elections in 2010. Thai political turmoil disrupted ASEAN and East Asia Summit meetings in April. In the Philippines, this year’s Balikatan exercise involved 6,000 U.S. troops and focused on responses to natural disasters. Meanwhile, the Philippine Congress is scheduling new hearings on the Visiting Forces Agreement for its alleged unduly favorable treatment of U.S. military personnel. Human rights concerns in Southeast Asia were raised again in the annual U.S. watch list on human trafficking with most of the region cited for an unwillingness or inability to stop the notorious trade. Finally, the U.S. praised Southeast Asian maritime defense cooperation in suppressing regional piracy as well as contributing to counter-piracy patrols in the Gulf of Aden.

US - Southeast Asia

January — March 2009Indonesia as Exemplar of Southeast Asia’s Importance

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s visit to Indonesia, part of her initial overseas journey to Asia, was enthusiastically received in the world’s most populous Muslim country. The secretary praised Indonesia’s thriving democracy as evidence of the compatibility of Islam and political pluralism. Noting Southeast Asia’s importance to the U.S., Clinton announced that the State Department would begin consideration of a process to sign ASEAN’s Treaty of Amity and Cooperation, a prerequisite for membership in the East Asia Summit. She also acknowledged that Washington’s harsh sanctions against Burma’s military junta had not changed that regime’s draconian rule but also pointed out that ASEAN’s engagement strategy was equally impotent. Nevertheless, she stated that the U.S. would consult with ASEAN in the process of reviewing its Burma policy. Meanwhile, ASEAN held its 14th summit in Thailand at the end of February. While the global economic crisis dominated the agenda, the future of a human rights commission mandated by ASEAN’s new Charter proved the most contentious, with the more authoritarian ASEAN members insisting that noninterference in domestic affairs should remain the underlying principle of any human rights body.

US - Southeast Asia

October 2017 — December 2008Thai Political Turmoil Impacts ASEAN

Political conflict in Thailand between the ruling, rural-based pro-Thaksin People Power Party (PPP) and an urban elite coalition calling itself the People’s Alliance for Democracy (PAD) – though actually opposing democratic elections – turned violent in November and shut down Bangkok and the capital’s airports for several days. The PPP government was forced to postpone the ASEAN summit scheduled for early December because of the violence and rescheduled the meeting for February 2009 to the dismay of other ASEAN leaders. Nevertheless, the new ASEAN Charter, which provides the Association with a legal personality for the first time, was activated at a special meeting of ASEAN foreign ministers in Jakarta on Dec. 15. Southeast Asian leaders welcomed Illinois Sen. Barack Obama’s election as the next U.S. president although some commentators noted that the Democratic Party has sometimes followed a trade protectionist policy when the U.S. economy is in difficulty. The Democrats have also taken a tougher position on human rights. In general, though, no significant change is foreseen in U.S. policy for Southeast Asia under President-elect Obama.

US - Southeast Asia

July — October 2008U.S. Responds to Southeast Asian Political Turmoil

The cancellation of a draft peace agreement between the Moro Islamic Liberation Front and the Philippine government triggered renewed violence in the Philippine south and allegations that U.S. forces are involved in Philippine armed forces suppression activities. Both Manila and Washington deny the charges, though U.S. Special Operations Forces have been training the Philippine military in Mindanao since 2002. The U.S. has added new sanctions against Burma’s junta and continues to criticize its political repression, while aid for the victims of Cyclone Nargis remains under the Burmese military’s control. Ratification for ASEAN’s new Charter by its member states has been achieved by eight of the 10 countries. The delays include concerns in the Indonesian and Philippine legislatures about Burma’s detention of Aung San Suu Kyi as well as the junta’s insistence that any ASEAN Human Rights Commission be toothless. The U.S. State Department has expressed concern over the Malaysian government’s arrest of opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim on suspicious sodomy charges. Malaysian leaders responded angrily that the U.S. complaint constitutes interference in Kuala Lumpur’s domestic politics and that Washington is not “the policeman of the world.”

US - Southeast Asia

April — June 2008U.S. Frustrated as Burma Obstructs Cyclone Relief

Cyclone Nargis, which devastated Burma’s Irrawaddy delta in early May killing tens of thousand and leaving 1.5 million homeless, was met with international concern and the offer of large-scale U.S. assistance via navy ships in the vicinity for the annual Cobra Gold exercise. Burma’s junta, however, obstructed international humanitarian assistance, fearing that Western powers would use the opportunity to overthrow the generals. So, in contrast to the massive aid effort for Indonesia in the December 2004 tsunami aftermath, assistance has only trickled into Burma, and mostly controlled by the Burmese military. ASEAN, in collaboration with the UN, appealed to Burmese authorities to open the country to aid providers, but the most it has been able to accomplish is to insert 250 assessment teams into some of the hardest hit areas to survey the population’s needs. U.S. aid has been limited to more than 100 C-130 flights out of Thailand whose cargos are delivered into the hands of the Burmese military.

US - Southeast Asia

January — March 2008Domestic Drama and a New Path to ASEAN

On a bilateral level, U.S. relations with Southeast Asia held steady in the face of complicated political transitions in Thailand and Malaysia. Incremental gains were seen in security ties with U.S. allies and partners in the region – Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Singapore – while two issues remaining from the Vietnam War era complicated relations with Vietnam and Cambodia. Although the U.S. is no closer to signing the ASEAN Treaty of Amity and Cooperation, three new initiatives with ASEAN were put onto the table in early 2008, suggesting an alternative path to a stronger regional role for the U.S. However, Burma’s deteriorating situation casts a long shadow over U.S. bilateral and regional relations with Southeast Asia. The regime’s determination to go forward with a constitutional referendum in May is creating new fissures within the region and will make it more difficult for Washington to pursue comprehensive plans of any kind to strengthen relations with ASEAN.

US - Southeast Asia

October — December 2007The New ASEAN Charter Bedeviled by Burma’s Impunity

While the ASEAN 10 celebrated the association’s 40th anniversary by initialing its first Charter giving the group a legal personality at its November Singapore summit, Burma’s vicious crackdown on thousands of democracy and human rights demonstrators dampened the exultations. The Bush administration placed new sanctions on the Burmese junta, including the Treasury Department’s freezing of companies’ assets doing business in Burma and possibly even banks that handle their transactions. Moreover, Washington warned that an ASEAN-U.S. Trade Agreement now depends on Burma’s genuine progress toward democracy – an unlikely prospect as long as the junta continues to rule. For the Philippines, Washington has promised more economic and military aid focused primarily on the restive south but partially conditioned on a better human rights performance. Human rights concerns also dominated U.S. relations with Malaysia and Thailand with respect to Kuala Lumpur’s crackdown on ethnic Indian demonstrations and Thailand’s harsh treatment of Muslim dissidents in the southern provinces.

US - Southeast Asia

June — September 2007Burma Heats up and the U.S. Blows Hot and Cold

Asia’s largest multilateral naval exercise in decades took place in the eastern Indian Ocean Sept. 4-9, involving ships and aircraft from the U.S., India, Japan, Australia, and Singapore. Extensive combat, antiterrorism, and humanitarian assistance scenarios were included. President Bush condemned the Burmese junta for its brutal suppression of anti-regime demonstrations. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice bypassed the annual ASEAN Regional Forum gathering for the second time in three years while President Bush postponed the U.S.-ASEAN summit originally scheduled for September and left the Sydney APEC summit a day early, demonstrating that Asia’s importance continues to take second place to Washington’s Middle East tribulations. Antiterrorist support dominated U.S.-Philippine relations this quarter. The Indochinese states were featured in several U.S. statements on trade and human rights in Vietnam, Hmong refugees from Laos, and counterterrorism training for Cambodia. Washington continued to press for the restoration of democracy in Thailand, looking forward to elections in December.

US - Southeast Asia

April — June 2007Better Military Relations and Human Rights Concerns

Military-to-military ties with Indonesia were significantly enhanced this quarter as plans were made for joint training that included counterterrorism for the first time. Jakarta also supported UN Security Council sanctions against Iran’s nuclear program despite negative domestic reactions for opposing a fellow Muslim country. Regarding the Philippines, a U.S. Congressional hearing condemned extra-judicial killings and the impunity with which some elements of Philippine security forces have been treating political opponents and journalists. U.S. economic aid to the southern Philippines was praised by the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, currently in autonomy negotiations with Manila. U.S. Special Forces continue to train Philippine soldiers in the south to suppress the Abu Sayyaf terrorists with recent significant successes. Thailand rejected a U.S. offer to provide assistance to Bangkok’s counterinsurgency efforts in the Thai south. U.S. officials regularly remind the Bangkok military caretaker government about the importance of restoring democracy by the end of the year. The two countries are also in a dispute over patent protection for pharmaceuticals needed for public health in Thailand. ASEAN leaders have urged the U.S. to strengthen its Southeast Asian ties and not hold them hostage to U.S. Burma policy. Vietnam President Triet’s June visit to the U.S. led to new economic arrangements, but the visit was marred by Congressional complaints over human rights violations in Vietnam.

US - Southeast Asia

January — March 2007Military Support and Political Concerns

U.S. military support for Philippine counterterrorism forces has led to significant gains against the Abu Sayyaf radical Islamist criminal gang in the southern Philippines, although Philippine complaints against the Visiting Forces Agreement continue in the aftermath of the rape conviction of a U.S. Marine. Manila passed long-awaited anti-terrorism legislation to Washington’s applause. The U.S.-backed UN Security Council (UNSC) resolution condemning Burma’s human rights violations was defeated by joint Chinese-Russian vetoes, although a majority of the UNSC members supported the resolution. Free Trade Agreement negotiations with Malaysia have run up against significant labor and service industry obstacles, while former Prime Minister Mahathir Mohammad convened a private tribunal to condemn the Bush administration’s actions in Iraq. Meanwhile, Indonesia’s importance for U.S. security was emphasized in a visit by Gen. Peter Pace, chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs, and U.S. naval visits to Vietnam and Cambodia signaled growing warmth in those relations.

US - Southeast Asia

October — December 2006Bush Reaches Out at APEC

In his November visit to Southeast Asia attendant to the Hanoi Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Leaders Meeting, President George W. Bush raised the prospect of an Asia-Pacific free trade area, discussed implementation of the ASEAN-U.S. Enhanced Partnership that emphasizes good governance, praised Indonesia for the success of the peace process in Aceh, and assured Vietnamese officials that permanent normal trade relations would be approved by the U.S. Congress by year’s end. (It was.) The Visiting Forces Agreement in the Philippines survived a severe test when a U.S. Marine was convicted of rape and sentenced to 40 years in a Philippine prison. The conviction is being appealed. At the APEC summit, Philippine President Gloria Arroyo asked the U.S. president for a “deeper and broader” U.S. role in combating Philippine terrorists as well as in the ongoing peace process with the Moro Islamic Liberation Front. Although continuing to press the Thai coup leadership to restore democracy, Washington announced plans to hold the annual multinational Cobra Gold military exercise in May 2007 and continued to provide assistance for counterterrorism.

US - Southeast Asia

July — September 2006U.S. Strengthens Ties to Southeast Asian Regionalism

Indonesia and Malaysia chastised the United States for backing Israel in the July-August Hezbollah Lebanon war, though both Jakarta and Kuala Lumpur subsequently offered peacekeeping forces to monitor the ceasefire. Washington signed a trade and investment framework agreement with ASEAN at July ministerial meetings and is considering appointment of an ambassador to ASEAN as well as creating a new Southeast Asian financial post in the Treasury Department. On the military dimension, the U.S. is delivering spare parts for the Indonesian air force and has initialed a new defense arrangement – the Security Engagement Board – with the Philippines that will focus on humanitarian aid, civic engagement, and counterterrorism training in insurgent-ridden Mindanao. Washington has also placed Burma’s human rights violations on the UN Security Council agenda and enhanced economic and military relations with Vietnam. In response to the Sept. 19 Thai coup, the U.S. expressed disappointment in the setback to democracy by an important regional ally but did not insist that deposed Prime Minister Thaksin be restored to power.

In June visits to Singapore, Indonesia, and Vietnam, U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld emphasized the importance of a continued robust U.S. role in Asian security as well as the necessity for security collaboration with U.S. Asian partners. Arms smuggling and espionage scandals in Indonesia and the Philippines respectively revealed some strains in U.S. relations but did not weaken mutual security activities. The United States – along with Japan, India, and China (all of whom rely on the Malacca Strait for much of their seaborne commerce) – offered the littoral states of Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia assistance for improving their anti-piracy capabilities. Washington has also begun to send equipment to Indonesia’s armed forces now that the ban on such transfers has been lifted. Finally, U.S. trade negotiations with Vietnam have led to the signing of a Permanent Normal Trade Relations agreement, the final stage before Hanoi’s admission to the World Trade Organization.

US - Southeast Asia

January — March 2006U.S. Ratchets Up Regionalism and Boosts Ties with Muslim States

Determined to reverse impressions that the United States is out of sync with regional dynamics, the State Department floated the idea of a formal U.S.-ASEAN Summit and speculated publicly on a possible U.S. role in the next East Asia Summit. Condoleezza Rice made her first visit to Jakarta as secretary of state, while U.S. Trade Representative Rob Portman launched negotiations with Malaysia on a free trade agreement in Washington. Southeast Asia’s two oldest democracies, Thailand and the Philippines, spent much of the quarter in political turmoil. Protests in Thailand put U.S.-Thai Free Trade Agreement (FTA) talks on ice, but the Balikatan 2006 exercises went forward in the Philippines as planned, despite a declaration of national emergency. As the U.S. and Vietnam moved closer to agreement on Hanoi’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO), the focus began shifting to Congress and the debate on Permanent Normal Trade Relations. In Cambodia, the return of exiled opposition leader Sam Rainsy – and hints that Rainsy could join the government coalition – led Washington to contemplate shifts in U.S. policy.

US - Southeast Asia

October — December 2005Military Relations Restored with Indonesia, While U.S. Passes on the First East Asia Summit

Full-scale military relations have been restored with Indonesia, including Foreign Military Financing for lethal equipment, in recognition of the country’s democratic practices and its importance for the U.S. global war on radical Islamic extremism. Although not a member of the first East Asia Summit (EAS), Washington launched an Enhanced Partnership with ASEAN by agreeing to a multi-dimensional Plan of Action that includes additional cooperation on security, trade, and investment. U.S. relations with the Philippines were complicated by reports in the local media of classified U.S. assessments of Philippine politics that emphasized vulnerabilities in President Arroyo’s government. While Philippine-U.S. joint military exercises continued, the arrest of five U.S. marines on rape charges led to calls in the Philippine Congress for amending the Visiting Forces Agreement. The U.S. may provide some equipment and training for anti-piracy patrols in the Malacca Straits conducted by Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand. Under Secretary of State Karen Hughes’ visit to the region led to her enthusiastic endorsement of Malaysia’s politics of inclusion as a possible model for Iraq.

US - Southeast Asia

July — September 2005Misses and Hits

Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice’s decision to bypass the annual ASEAN and ARF meetings in her first year as secretary is seen as a snub by Southeast Asian leaders and interpreted to be a sign of the low level of the region’s importance to Washington. Nevertheless, U.S. security cooperation seems to be increasing with the littoral states in the Strait of Malacca, through bilateral exercises with ASEAN states’ armed forces, military sales to Thailand, a new security agreement with Singapore, and continued anti-insurgency training for Philippine forces in Mindanao. Moreover, the U.S.-led multinational Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI) held its first South China Sea exercise on the interdiction of weapons of mass destruction (WMD). Finally, Vietnam was added to the list of Southeast Asian states participating in the U.S. International Military and Educational Training (IMET) program.

US - Southeast Asia

April — June 2005Summitry Hints of a More Activist Approach

As the new State Department team settled in, the U.S. attempted to maintain the heightened momentum in relations with Southeast Asia created by the tsunami relief effort earlier this year. In May, Deputy Secretary of State Robert Zoellick travelled to Singapore, Thailand, the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Malaysia, using the trip to proclaim a new policy of greater attention to the region. President George Bush hosted Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY) in May and Vietnamese Prime Minister Phan Van Khai in June, inaugural visit to Washington for both leaders. Also in June, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld attended the Shangri-La security meeting in Singapore and used the spotlight to criticize Beijing’s presumed expansionist aims. Rumsfeld’s choice of Singapore as a venue for the remarks, combined with Zoellick’s listening tour, signaled growing interest in Washington in China’s increasing influence in Southeast Asia.

Indonesia was of two minds about the U.S. A recent Pew survey reported improvement of the U.S. image there because of tsunami aid, but demonstrations in Jakarta over the Newsweek story on Islamic prisoner abuse at Guantanamo Bay showed fresh resentment. U.S. military cooperation moved incrementally toward a more regional approach, while several rounds of bilateral trade talks were held. Human rights remained central to U.S. policy in Burma as Washington prepared to renew sanctions and made clear its opposition to Rangoon’s chairmanship of ASEAN in 2006.

US - Southeast Asia

January — March 2005Aid Burnishes U.S. Image but Other Concerns Persist

A massive U.S. relief effort led by the U.S. Navy for the tsunami-devastated north Sumatran coast has burnished America’s image in Indonesia, which had sunk to a record low after Washington’s invasion of Iraq. Even large Indonesian Muslim organizations that previously voiced anti-American views have praised U.S. humanitarian activities in Banda Aceh. The Bush administration has seized the new positive spirit of Indonesian-U.S. relations to press Congress for the restoration of training and education programs for the Indonesian military that had been suspended since 1992. On the anti-terrorist front, the U.S. expressed disappointment at an Indonesian court’s acquittal of radical Jemaah Islamiyah cleric Abu Bakar Bashir on allegations of involvement in the 2002 Bali and 2003 Jakarta Marriott bombings. Bashir received a relatively light 30-month sentence – half of which has already been served – for knowing about the terrorists’ plans. The U.S. State Department’s annual Human Rights Report criticized the Thai government killings of southern Thai Muslims during efforts to suppress secession activities.

US - Southeast Asia

October — December 2004Elections, Unrest, and ASEAN Controversies