Articles

Japan - China

Japan - China

September — December 2023The Sparring Continues

Several senior-level contacts failed to narrow the gap between Japan and China. Xi Jinping and Kishida Fumio met at APEC for 65 minutes in November to discuss topics including a buoy placed in what Japan regards as its territorial waters, China’s lack of cooperation on North Korea’s nuclear program, Beijing’s resumption of drilling in a disputed section of the East China Sea, and the detention of Japanese nationals on vaguely worded charges. China complained about Japan’s enhanced defense relationship with the US and other countries, its chip alliance with the US aimed at excluding China, the continued release of allegedly contaminated water from the disabled Fukushima plant, as well as Japan’s support for Taiwan. There was no resolution of any of these issues. Komeito leader Yamauchi Natsuo visited Beijing with a letter from Kishida; its contents have not been publicly disclosed but it had had no discernible results. Foreign Minister Kamikawa Yoko’s meeting with counterpart Wang Yi at a trilateral meeting of foreign ministers in South Korea, also in November, was similarly unproductive. With Kishida seemingly losing support of his own party and likely to be replaced soon, Japan has little leverage in negotiations.

Japan - China

May — August 2023From Talking Past Each Other to Barely Talking

China’s mid-August decision to allow group travel to Japan days ahead of the 45th anniversary of the Treaty of Peace and Friendship between the two nations as well as indications that China would be open to a meeting between Xi Jinping and Fumio Kishida on the sidelines of the Group of 20 (G20) leaders’ summit in India in September gave hope for improvement in China-Japan ties. The optimism proved short-lived. Chinese media responded that Japan would first have to turn away from following the US lead, stop encouraging Taiwanese pro-independence forces, and strictly abide by the four communiques signed between Beijing and Tokyo. China’s protests over Japan’s release of radioactive water culminated in a total ban on Japanese marine products. The PRC also expressed annoyance with Japanese restrictions on the export of computer chips, the ministry of defense’s release of its annual Defense of Japan 2023 white paper, Tokyo’s closer relations with NATO, and its tripartite agreement with South Korea and the US. Japan expressed uneasiness with Russia-China cooperation and became concerned with renewed Chinese interest in Okinawa, with its purchases of Japanese land, cyberattacks, and its refusal to import Japanese seafood products.

Japan - China

January — April 2023Talking—But Talking Past Each Other

The 17th China-Japan Security Dialogue resumed in late February after a four-year pause but produced no resolution to outstanding problems. In early April, Chinese and Japanese foreign ministers also met for the first time since 2019, with the four-hour meeting similarly unproductive. The Chinese side expressed annoyance with Tokyo for its cooperation with the United States, its support of Taiwan, the release of Fukushima nuclear-contaminated wastewater into the ocean, and Tokyo’s recent restrictions on semiconductor equipment exports. The Japanese foreign minister sought, but did not obtain, information on a Japanese national who had been arrested on spying charges, complained about Chinese intrusions into the territorial waters around the disputed Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, and stressed the importance of stability in the Taiwan Strait. There was no mention of the long-postponed state visit of Xi Jinping to Tokyo as a matter of reciprocity for former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo’s visit to Beijing.

Japan - China

September — December 2022A Period of Cold Peace?

In the sole high-level meeting in the reporting period, on the sidelines of the APEC meeting in Bangkok in November, General Secretary/President Xi Jinping and Prime Minister Kishida Fumio essentially talked past each other. At an earlier ASEAN+3 meeting in Phnom Penh, Premier Li Keqiang and Kishida not only talked past each other but pointedly walked past each other. There was no resolution of major issues: the Chinese position is and remains that Taiwan is a core interest of the PRC in which Japan must not interfere. Japan counters that a Chinese invasion would be an emergency for Japan. On the islands known to the Chinese as the Diaoyu and to the Japanese as the Senkaku, Tokyo considers them an integral part of Japan on the basis of history and international law while China says the islands are part of China. On jurisdiction in the East China Sea, Japan says that demarcation should be based on the median line and that China’s efforts at unilateral development of oil and gas resources on its side of the median are illegal. Beijing does not recognize the validity of the median line.

Japan - China

May — August 2022Few Positive Signs and Much Negativity

The tone of China-Japan relations became more alarmist on both sides with long-anticipated plans to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the normalization of diplomatic relations still clouded with uncertainty. Several related events were canceled or postponed sine die.

Internationally, Prime Minister Kishida was exceptionally active, attending meetings of the Quad, the G7, NATO, and Shangri-La Dialogue, where he delivered the keynote address. A common theme was attention to a Free and Open Pacific (FOIP) and the need for stability in the region, both of which Beijing sees as intended to constrain China. At NATO, Kishida met with US and South Korean representatives for their first trilateral meeting in nearly five years and suggested the possibility of joint military exercises.

Meanwhile, China continued pressure on Taiwan and the contested Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands. Although Foreign Minister Wang Yi and State Councillor Yang Jieqi were active internationally, Xi Jinping himself has not ventured outside the Chinese mainland since January 2020 save for a brief, tightly controlled visit to Hong Kong, which is unquestionably part of China. Speculation ranged from concern with his health to worries that he might be toppled by unnamed enemies—who these enemies are and what degree of influence they wield are the topics of much discussion, since Xi has through selective arrests of potential rivals and the country-wide imposition of his thoughts, effectively silenced public expression of dissident opinions.

After former Prime Minister Abe was assassinated on July 8 in an incident unrelated to foreign policy, the Chinese government sent condolences, though no Chinese representative attended the wake. A state funeral is to be held in the fall, with much speculation on who will represent the PRC.

Japan - China

January — April 2022The Cold Peace Continues

Intermittent declarations of intent to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the normalization of relations notwithstanding, China-Japan tensions continued unabated. No high-level meetings were held between the two, but rather between each and its respective partners: China with Russia, and Japan with members of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue as well as separately, with Australia, New Zealand, and the United States. All of the latter had apprehension over Chinese expansionism as their focus. Both the Chinese and Japanese economies sputtered in response to COVID lockdowns and the rising cost of energy but trade relations were robust and expected to increase as the number of new COVID cases declines. However, each side continued to develop its military capabilities, with China continuing to voice irritation with Japan for its obvious, though largely tacit, support for Taiwan’s autonomy.

Japan - China

September — December 2021Red Lines Are Tested

Chinese Communist Party leader Xi Jinping’s long-expected and often postponed—even before the pandemic—state visit to Japan was not even spoken of during the reporting period. In the closing days of the year, the defense ministers of the two countries met virtually but, at least according to published accounts, simply reiterated past positions and hopes for cooperation in the interests of regional stability. Japan did not receive the assurances it sought on the implications of the PRC’s new Coast Guard law. China repeatedly pressed the Japanese government for support for the Beijing Winter Olympics, expressing dissatisfaction with the lack of official representation announced by Tokyo. Although trade was brisk, economic growth in both countries remained impacted by quarantines and the uncertain investment climate in China. China complained about closer Taiwan-Japan relations

Japan - China

May — August 2021A Chilly Summer

China and Japan continued to vie over a wide variety of issues including economic competitiveness, jurisdiction over territorial waters, World War II responsibilities, representation in international organizations, and even Olympic and Paralympic medals. The Japanese government expressed concern with the increasingly obvious presence of Chinese ships and planes in and around areas under its jurisdiction, with Chinese sources accusing Japan of a Cold War mentality. Nothing was heard of Xi Jinping’s long-planned and often postponed official visit to Tokyo. Also, Chinese admonitions that Japan recognize that its best interests lay not with a declining United States but in joining forces with a rising China were conspicuous by their absence.

Japan - China

January — April 2021The Gloves Come Off

After several years of seeking to counter each other while insisting that their relations were at a recent best, Tokyo and Beijing became overtly contentious. A major event of the reporting period was China’s passage, and subsequent enforcement, of a law empowering its coast guard to take action, including through the use of force, to defend China’s self-proclaimed sovereignty over the Japanese administered Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea. Heretofore reluctant to criticize Beijing over its actions in Xinjiang and Hong Kong, Japanese Foreign Minister Motegi Toshimitsu finally did so in April, and pledged to work with the United States to resolve China-Taiwan tensions. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi warned that a continuation of such moves would cause Chinese-Japanese ties to hit bottom and threatened retaliation for any interference on Taiwan. No more was heard about a long-postponed Xi Jinping visit to Japan.

Japan - China

September — December 2020Treading Water

Perhaps the biggest news of the last third of 2020 was that Xi Jinping’s often-postponed state visit to Japan will not take place in spring 2021 and may be postponed to September 2022, in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the normalization of China-Japan diplomatic relations. Both countries’ economies recovered well from the pandemic, with robust trade between them even as they continued to snipe at each other politically and upgrade their military capabilities. China continued to expand its presence in waters of the East China Sea claimed by Japan.

Japan - China

May — August 2020The Velvet Gloves Fray…Slightly

Major concern in this period centered around the future of Sino-Japanese relations in the post-Abe era, with most analysts predicting that there would be little change. China’s impressive, though credit-fueled, rebound from the coronavirus pandemic as Japan’s economy sharply contracted indicates that Tokyo will seek to maximize trade with the PRC.

Xi Jinping’s long-awaited state visit to Japan is on indefinite hold, with concern for the pandemic a convenient explanation for underlying multiparty opposition due to Beijing’s assertive actions in contested areas and its repressive measures in Hong Kong and Xinjiang. Differences of opinion remain on the wording of a so-called 4th Sino-Japanese Communique that is much desired by Beijing.

Japan - China

January — April 2020Sino-Japanese Relations: In a Holding Pattern

Politically, the major news in Japan-China relations was that Xi Jinping’s long-anticipated state visit was postponed. While the coronavirus was a factor, the two sides had also been unable to agree on the text of the Fourth Communiqué, and there was considerable opposition within Japan to the visit due to issues between them. Several major Japanese companies announced major investments in the People’s Republic of China, even as the Japanese government agreed to subsidize companies to move their supply chains out of the country.

Japan - China

September — December 2019Speaking Softly but Planning for the Worst

As Tokyo continued to press unsuccessfully for a date on Xi Jinping’s state visit to Japan, frictions continued on matters such as the number of Japanese nationals detained in China, human rights concerns involving Xinjiang and Hong Kong, and Japan’s tentative reaction to participation in both the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership and the Belt and its Road Initiative. Trade relations remained strong despite declining economic growth in China and near stagnation in Japan, with both sides continuing to enhance their defense capabilities.

Japan - China

May — August 2019External Smiles, Internal Angst

Chinese and Japanese relations have been cordial during the summer months, but tensions over history, economics, disputed territories, and military expansion continue to simmer. Several meetings failed to reach consensus on issues. China continued to tighten its de facto control over disputed territories as Japan reinforced its capabilities to defend those areas. Several major Japanese corporations announced plans to move production out of China, citing concerns with the US-China trade war. Worsening relations between Seoul and Tokyo, and in particular Seoul’s decision to end an intelligence-sharing agreement, could weaken plans for joint resistance to Chinese and North Korean activities. No date has been set for Chairman Xi Jinping’s long-delayed reciprocal state visit to Japan.

Japan - China

January — April 2019Warm but Wary

Sino-Japanese interactions were less prominent in the early months of 2019, with the Chinese government focused on its Belt and Road Forum and the Japanese with the imperial abdication. Although President Xi Jinping has committed to attending the G20 Summit in Osaka in late June, no date has been set for a state visit to reciprocate Prime Minister Abe’s fall 2018 visit to Beijing. There is speculation that the Chinese are seeking prior commitment to a fifth communiqué, which would be controversial in Japan. The generally cordial atmospherics of lower-level talks belied tensions over territorial disputes, intellectual property rights, and cybersecurity.

Japan - China

September — December 2018Warmer Political and Economic Relations, Continuing Military Concerns

Prime Minister Abe’s long coveted visit to Beijing gave the appearance of better China-Japan relations, although Chinese President Xi Jinping has yet to confirm a date for the expected reciprocal visit. Trade ties were strong, with Japanese firms taking tentative steps toward participating in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). As China’s GDP growth slowed, Japan’s showed modest gains. Instances of economic rivalry in Southeast Asia and Africa continued even as both affirmed the need for cooperation. Each side expressed alarm at the other’s robust defense preparations, amid numerous, though somewhat diminished in numbers, complaints from Japan about incursions into its territorial waters and airspace. Tokyo continued to court countries that share its concerns about Chinese expansion.

Japan - China

May — August 2018Warm Words, Underlying Anxieties

Government-to-government relations were cordial over the summer, with the public expression of differences minimized to emphasize their common opposition to US protectionist trade policies. Bilateral trade and tourism posted impressive gains. Both leaders seemed likely to continue in office, though China’s annual Beidaihe meeting of power brokers allegedly criticized the disappointing results of President Xi Jinping’s economic restructuring program, his aggressive foreign policies, and the excesses of his cult of personality. Unimpressive popularity polls notwithstanding, Prime Minister Abe Shinzō had solid support for re-election as president of the Liberal Democratic Party and is therefore likely to win a third consecutive term as prime minister. Abe remained optimistic about receiving an invitation for a state visit to Beijing. However, Japan continued to complain about China’s military expansion and to strengthen its defenses. Summing up China-Japan relations 40 years after normalization, the Yomiuri Shimbun noted that coolness persisted despite bilateral exchanges of people and money.

Japan - China

January — April 2018Warmer Words, Continuing Defense Preparations

Chinese President Xi Jinping successfully presided over the Boao Forum indicating progress toward establishing China as the fulcrum of the international trading system. Meanwhile, Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzō’s political future was clouded by the Moritomo Gakuen scandal. Formal high-level dialogue between Beijing and Tokyo, interrupted since September 2010 was cautiously reinstated in April. In the same month, lower-level military exchanges resumed after a six-year hiatus. Despite talk of resetting relations, there was no resolution of key issues such as the disposition of disputed islands in the East China Sea or of present-day Japanese responsibility for the country’s conduct during World War II. As for trade, although both China and Japan are committed in theory to early conclusion of the Regional Economic Cooperation Partnership agreement, Japan favors a deal closer to the Trans-Pacific Partnership while China wants additional concessions to support its economic reform goals. Nonetheless, China hopes to obtain Japanese participation in its Belt and Road Initiative.

Japan - China

September — December 2017Managing a Fragile Relationship

As China’s President Xi Jinping entertained national leaders in Beijing, Japan’s Prime Minister Abe Shinzō made appearances at the opening of the United Nations General Assembly and the New York Stock Exchange, and authored an op-ed in The New York Times. Abe’s common theme was denunciation of North Korea’s provocative behavior, adding that China must play a greater role in curbing its activities. Abe also indicated Japan would consider supporting companies that participated in the Belt and Road Initiative and partner with China in underwriting aid to African countries, while hinting strongly that he would like an invitation for a state visit. China is holding fast to its conditions for a formal meeting: Japan must agree there is a dispute over Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands ownership and show that it has come to terms with its misconduct during World War II. At yearend, Beijing’s Global Times asserted that bilateral ties had broken out of their slump while Japanese papers reported a senior LDP official as stating the two sides had pushed their relations to a new state, enabling them to discuss the future.

Japan - China

May — August 2017No Setbacks, No Progress

The pattern of warm trade and cold politics continued over the summer of 2017. No discernible progress was made in resolving issues between Japan and China. Leadership interaction was limited, while economic relations showed some signs of improving and tensions in the East China Sea dominated defense activity. At the end of September, the government-sponsored China Daily opined that it was “no exaggeration to say that the past five years have been among the darkest days in Sino-Japanese ties since the two established formal diplomatic ties.”

Japan - China

January — April 2017No Pyrotechnics, No Progress

Though free of the large-scale anti-Japanese demonstrations and acerbic exchanges that have characterized the recent past, the cold peace between China and Japan continued in the early months of 2017. There were no meetings of high-level officials, and none were scheduled. Mutual irritants continued on familiar topics: defense and territorial issues, Taiwan, trade and tourism, and textbooks and history.

Japan - China

September — December 2016Abe-Xi Met; Diplomats Talked; Wait ‘Til Next Year…

Prime Minister Abe and President Xi met twice in the last four months of 2016. Both committed to advancing the relationship during 2017, taking advantage of the opportunities presented by historic anniversaries – the 45th anniversary of normalization and the 40th anniversary of the Japan-China Friendship Treaty. Both leaders also committed to the early implementation of an air and maritime communications mechanism. Notwithstanding the increasing air and maritime interactions between the PLA and the Japanese SDF and Coast Guard, working-level officials were unable to reach agreement. At the end of the year, the Abe government announced a record high defense budget for 2017; days later the China’s aircraft carrier transited in international waters between Okinawa and Miyakojima into the western Pacific. Meanwhile public opinion polling revealed growing pessimism in Japan with respect to China and Japan-China relations.

Japan - China

May — August 2016No Lack of Dialogue, Results – TBD

There was no lack of high-level bilateral dialogue over the summer months with the foreign ministers meeting three times between late April and the end of August. There were several other exchanges in between including a meeting between Prime Minister Abe and Premier Li in July at the Asia-Europe Meeting in Ulaanbaatar. Despite the dialogue, strong differences continued to mark the relationship, in particular on issues related to the South China Sea and the East China Sea. Tensions heightened in June when a PLA Navy ship entered Japan’s territorial waters off Kagoshima and again in August when Chinese fishing boats and Coast Guard ships swarmed into the Senkakus, entering Japan’s contiguous zone and territorial waters despite repeated high-level protests.

Japan - China

January — April 2016Staying on a Test Course

Citing his November meeting with Premier Li as evidence, Prime Minister Abe found relations with China improving in his Diplomatic Report to the Diet. Chinese officials took a more cautious view. While acknowledging progress, China’s ambassador to Japan called attention to unstable elements in the relationship and Foreign Minister Wang Yi accused Japan of “double dealing” in its relations with China. Issues related to the East China Sea and the South China Sea continued to trouble the relationship. Chinese Coast Guard ships made incursions into Japan’s territorial waters in the Senkakus while Japan continued to strengthen its military presence in Okinawa and the southwest islands. The foreign ministers met at the end of April.

Japan - China

September — December 2015Moving in the Right Direction

Senior political and diplomatic contacts expanded in late 2015. Prime Minister Abe met Premier Li in October and President Xi briefly in November. Meanwhile, maritime issues dominated the policy agenda: China’s natural gas exploration in the East China Sea, incursions into Japan’s territorial waters near the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, and China’s land reclamation projects in the South China Sea. History issues also punctuated the period – the September victory parade in Beijing, at UNESCO, and the anniversary of the Nanjing Massacre in December. Nevertheless, there was a general sense that relations were moving in the right direction.

Japan - China

May — August 2015To August 15 – Toward September 3

The summer months witnessed a parade of senior Liberal Democratic Party figures traveling to Beijing. The visits were aimed at sustaining positive political trends, securing an invitation for Abe to visit China, and anticipating issues related to Abe’s August statement commemorating the end of World War II. Meanwhile, China prepared to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression and the World Anti-Fascist War with a victory parade on Sept. 3. Against this backdrop, each country sought to enhance its security posture in the East China Sea and South China Sea, further besetting bilateral relations.

Japan - China

January — April 2015Gaining Traction

Despite ongoing discussions of history and present-day issues related to the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, there was a general sense in both Tokyo and Beijing that relations were slowly moving in the right direction. Meetings took place between senior diplomats and political leaders. Slowly gaining traction, engagement culminated in the April 22 Xi-Abe meeting in Bandung, Indonesia, featuring smiles, handshakes, and a 25-minute talk – a far different picture of the relationship than that presented at the November meeting in Beijing. However, Xi and other Chinese officials consistently made it clear that progress in restoring relations would depend significantly on Japan’s proper understanding of history, in particular Prime Minster Abe’s much anticipated statement commemorating the 70th anniversary of the end of the war.

Japan - China

September — December 2014A Handshake at the Summit

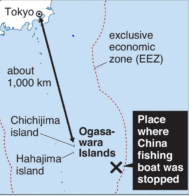

Prime Minister Abe realized his long quest for a summit with President Xi during the APEC meeting in Beijing. The picture of the encounter – Xi’s averted gaze at the handshake – spoke volumes, underscoring the politically sensitive issues that trouble the relationship: disputed history, Yasukuni, and the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. China commemorated several anniversaries: the victory over Japan on Sept. 3, the Mukden Incident on Sept. 18, and the Nanjing massacre on Dec. 13. In the East China Sea, Chinese Coast Guard ships regularly operated in Japan’s contiguous zone, while asserting administrative jurisdiction and frequently entering Japan’s territorial waters. Meanwhile, Chinese fishing boats engaged in coral poaching within Japan’s EEZ. Polls in both countries revealed a continuation of mutually strong negative feelings.

Japan - China

May — August 2014Searching for a Summit

Japan spent the summer months pressing for a summit. In remarks to the Diet, press conferences, and public speeches Prime Minister Abe made clear his quest for a summit with President Xi during the November APEC meeting in Beijing. A parade of Japanese political figures explored the possibility of a summit during visits to China. Beijing continued to point to the obstacles – Abe’s visit to Yasukuni Shrine and Japan’s failure to recognize the existence of a dispute over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands. Meanwhile, incursions by China’s Coast Guard into Japan’s territorial waters continued and two mid-air incidents heightened security concerns. Japanese investment in China plunged over 40 percent in the first half of the year, and history remained ever present.

Japan - China

January — April 2014Past as Prologue

History dominated the Japan-China relationship. Controversies over the Yasukuni Shrine, the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, Ahn Jung-geun, the Kono and Murayama Statements, Nanjing, compensation for wartime forced labor, and China’s seizure of a Mitsui ship over a wartime-related contract dispute marked the first four months, ending almost where the year began with Prime Minister Abe making an offering to the Yasukuni Shrine during the spring festival. Meanwhile, Chinese Coast Guard ships operated on an almost daily basis in the Senkakus, occasionally entering Japanese territorial waters. In response, Japan increased the presence of the Self-Defense Forces in the southwest islands.

Japan - China

September — December 2013Can We Talk?

China marked the first anniversary of Japan’s nationalization of the Senkaku Islands by reasserting its sovereignty claims to the islands and conducting Coast Guard patrols in the area, which continued on a regular basis through December. Tokyo called for dialogue with China without preconditions, while Beijing insisted that dialogue required Japan to admit the existence of a dispute over the islands. Meanwhile, business leaders continued to develop economic ties and Japanese companies in China began to recover from the profit doldrums that followed initial Chinese reaction to the nationalization. In late November, Beijing announced the establishment of its East China Sea ADIZ, which Tokyo found to be unacceptable and refused to recognize. Prime Minister Abe added more tension to the relationship when he visited Yasukuni Shrine.

Japan - China

May — August 2013Going Nowhere Slowly

Repeated efforts by the Abe government to engage China in high-level dialogue failed to produce a summit meeting. While Tokyo remained firm in its position on the Senkakus, namely that there is no territorial issue that needs to be resolved, Beijing remained equally firm in its position that Japan acknowledge the existence of a dispute as a precondition for talks. In the meantime, Chinese and Japanese patrol ships were in almost daily contact in the Senkaku/Diaoyu region, while issues related to history, Japan’s evolving security policy, Okinawa, and the East China Sea continued to roil the relationship. By mid-summer over 90 percent of Japanese and Chinese respondents to a joint public opinion poll held negative views of each other.

Japan - China

January — April 2013Treading Troubled Waters

The Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands controversy continued to occupy center stage in the Japan-China relationship. Trying to find political traction and advance a possible summit, Prime Minister Abe, at the end of January, sent Yamaguchi Natsuo, leader of his coalition partner New Komeito Party, to Beijing, where he met Xi Jinping. The meeting produced agreement on the need for high-level talks, which have yet to materialize. In response to Beijing’s efforts to have Tokyo admit the existence of a dispute over the islands, the Abe government continued to insist that a dispute does not exist. To demonstrate the contrary and challenge Japan’s administration of the islands, China increased the number and frequency of maritime surveillance ships deployed to the region. At the end of April, China’s Foreign Ministry for the first time applied the term “core interest” to the islands.

Japan - China

September — December 201240th Anniversary: “Fuggetaboutit!”

The Japanese government’s purchase of three of the Senkaku Islands from their private owner on Sept. 11 and the sovereignty dispute over the maritime space surrounding them dominated Japan-China relations. In short order after the purchase, anti-Japanese riots broke out across China, events scheduled to mark the 40th anniversary of normalization of relations were canceled, trade and investment plummeted, and political leaders engaged in public disputations. To underscore Beijing’s claims, Chinese government ships regularized incursions into Japan’s contiguous zone and territorial waters near the islands. As both governments held fast to their respective national positions, prospects for resolution appeared dim. Prime Minister-designate Abe Shinzo told a press conference in mid-December that there was “no room for negotiations” on the Senkakus.

Japan - China

May — August 2012Happy 40th Anniversary…? Part 2

The summer was not all about the Senkakus, but the islands did dominate developments in the bilateral relationship. The Ishihara Senkaku purchase plan went full speed ahead. By the end of August, Japanese citizens had contributed over 1.4 billion yen toward the purchase and the Tokyo Municipal Government had formally petitioned to conduct a survey of the islands prior to purchase. Meanwhile, Hong Kong activists landed on the islands, sparking diplomatic protests from Tokyo; Japanese activists followed with their own landing on the islands, sparking diplomatic protests from Beijing and anti-Japanese riots across China. Japan’s ambassador to China caused his own political storm in Tokyo when he expressed his personal view that the Ishihara plan could lead to a crisis in Japan-China relations. Relations suffered further as Tokyo hosted the convention of the World Uighur Congress and President Hu Jintao found a bilateral meeting with Prime Minister Noda inconvenient during a trilateral China-Japan-ROK meeting in Beijing. An alleged spy incident involving a Chinese diplomat served to further complicate relations. Japan’s 2012 defense white paper reiterated, longstanding, but growing concerns with China’s lack of transparency and the increasing activities of its navy in waters off Japan. Meanwhile public opinion on mutual perceptions continued a downward trend in both countries.

Japan - China

January — April 2012Happy 40th Anniversary

With both Tokyo and Beijing intent on celebrating the 40th anniversary of normalization, bilateral relations started well in 2012 – and quickly went downhill. Contested history returned in a controversy sparked by Nagoya Mayor Kawamura Takashi’s remarks questioning the reality of the Nanjing massacre. Repeated incidents in the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands involving ships of China’s State Oceanic Administration Agency and Japan’s Coast Guard kept the volatile issue of sovereignty claims politically alive. Both sides engaged in island naming games to enhance sovereignty and EEZ claims in the region. In April, Tokyo Gov. Ishihara Shintaro announced plans for the Tokyo Municipal Government to purchase three of the Senkaku Islands. With that, the relationship moved into May and Prime Minister Noda’s visit to China.

Japan - China

September — December 2011Another New Start

Noda Yoshiko succeeded Kan Naoto as prime minister of Japan in early September and met President Hu Jintao at the G20 Summit in Cannes and the APEC meeting in Honolulu. On both occasions, they agreed to take steps to strengthen the mutually beneficial strategic relationship. They reiterated that commitment during Noda’s visit to China at the end of December. Meanwhile, maritime safety and security issues in the East China Sea and the South China Sea continued as a source of friction. In both areas, Tokyo worked to create a maritime crisis management mechanism while Chinese ships continued to intrude into the Japan’s EEZ extending from the Senkaku Islands, keeping alive contentious sovereignty issues. Tokyo and Beijing were able to resolve a November incident involving a Chinese fishing boat operating in Japanese waters. Repeated high-level efforts by Tokyo to resume negotiations on joint development in the East China Sea failed to yield any progress.

Japan - China

May — August 2011Muddling Through

Private-sector contacts kept the bilateral relationship afloat while high-level official contact began to re-engage. Defense ministers met in June in Singapore and foreign ministers met in July in Beijing. In each instance, they agreed on the importance of advancing the strategic and mutually beneficial relationship. In early August, Japan’s Ministry of Defense released its 2011 Defense White Paper, which expressed concerns over China’s military modernization, its increasing activities in waters off Japan, and its “overbearing” conduct in the South China Sea. Eight days later, the Chinese aircraft carrier Varyag left port for initial sea trails. Meanwhile, activities in the Senkaku/Diaoyutai Islands area continued to generate political friction in both Tokyo and Beijing.

Japan - China

January — April 2011Looking for Traction

Old problems – the Senkaku fishing boat incident, the East China Sea, and China’s increasing maritime activities in waters off Japan – persisted in early 2011. Efforts by Japan to keep lines of communication open with China’s leadership included a visit to China by members of the Diet and Japan’s senior vice minister for foreign affairs at the end of January – the first high-level bilateral diplomatic engagement since the Senkaku incident. The China-Japan Strategic Dialogue resumed in Tokyo at the end of February. Less than two weeks later, the March 11 earthquake and tsunami hit Japan. China responded by providing emergency assistance and sending a rescue and medical team. Prime Minster Kan personally thanked China’s leadership and, in an article carried by the Chinese media, the Chinese people for their assistance, support, and encouragement. The Asahi Shimbun offered the hope that the crisis could serve as an opportunity for a fresh start in Japan’s relations with its Northeast Asian neighbors.

Japan - China

September — December 2010Troubled Waters: Part II

Reactions to the Sept. 7 Senkaku fishing boat incident continued to buffet the relationship. Both the East China Sea and the Senkaku Islands remain flashpoints in both countries. Anti-Japanese protests spread through China in mid-October and were followed by smaller-scale anti-Chinese protests in Japan. Efforts by diplomats to restart the mutually beneficial strategic relationship ran into strong political headwinds, which hit gale force with the public uploading of the Japan Coast Guard’s video of the September collisions on YouTube. Prime Minister Kan did meet China’s political leadership, but the Kan-Wen and the Kan-Hu meetings were hotel lobby or corridor meet-and-greets, with the Chinese taking care to emphasize their informal nature. In Japan, public opinion on relations with China went from bad in October to worse in December.

Japan - China

July — September 2010Troubled Waters

The quarter started well. The Kan government, emphasizing efforts to strengthen economic ties with China, appointed Niwa Uchiro, former president of the trading giant Itochu Corp., as Japan’s new ambassador to China. Talks to implement the June 2008 agreement on joint development of the East China Sea began in Tokyo in late July. Prime Minister Kan and all Cabinet members refrained from visiting Yasukuni Shrine on Aug. 15. In early September, Japan began the destruction of chemical weapons left behind in China by the Imperial Army at the end of the war. The quarter, however, ended in controversy. Sparked by the Sept. 7 incident in which a Chinese fishing boat operating near the Senkaku Islands collided with two Japanese Coast Guard ships, relations quickly spiraled downward. The Japanese Coast Guard detained the captain and crew setting off a diplomatic row that led to the Japanese ambassador being called in for a midnight demarche as well as the personal involvement of Premier Wen Jiabao before Japanese prosecutors released the ship’s captain on Sept. 24. China’s call for compensation and an apology went unanswered as of the end of the quarter.

Japan - China

April — June 2010Troubled Waters to Calm Seas?

The quarter began with China’s execution of Japanese nationals convicted of drug smuggling. This was followed shortly by large scale and unannounced naval exercises in international waters near Japan that involved PLA Navy helicopters buzzing Japanese surveillance destroyers. This was followed by Chinese pursuit of a Japanese research ship operating within Japan’s claimed EEZ. Meanwhile, Foreign Minister Okada chided his Chinese counterpart on China being the only nuclear-weapon state not committed to nuclear arms reduction. Nevertheless, high-level meetings continued throughout the quarter: Hatoyama and Hu in April, Hatoyama and Wen in May, Kan and Hu in June. At the meetings, China unexpectedly agreed to begin negotiations on the East China Sea at an early date and proposed a defense dialogue and defense exchanges, while both sides reaffirmed commitments to build “win-win” outcomes in the economic relationship and to advance the mutually beneficial strategic relationship.

Japan - China

January — March 2010All’s Well that Ends Well

The final report of the Japan-China Joint Study of History project, which was composed of studies by individual Japanese and Chinese historians and not a consensus document, was released at the end of January. While differences remained over issues related to Nanjing and postwar history, both sides expressed satisfaction with the three-year effort and committed to follow-on studies. At the same time, efforts to reach an implementing agreement on joint development in the East China Sea failed to make progress. Even the decline to single-digit growth in China’s 2010 defense budget, while welcomed in Japan, was met with skepticism and calls for greater transparency. Meanwhile, China protested Japan’s appropriations to support conservation and port construction on Okinotorishima. Then, with hopes fading in Japan for a resolution of the two-year running controversy over contaminated gyoza imported from China, Chinese authorities at the end of March announced the arrest of a former employee at the Tianyang Food Plant in Hebei Province who admitted under questioning that he had injected pesticide into the frozen gyoza.

Japan - China

October — December 2009Gathering Momentum

A flurry of high-level political and diplomatic contacts marked the quarter. The engagement culminated in the December visit of DPJ Secretary General Ozawa Ichiro to China and his meeting with President Hu Jintao followed by the visit of Vice President Xi Jinping to Japan and his audience with Emperor Akihito. Both Japanese and Chinese political leaders repeatedly made clear their intentions to advance the bilateral relationship. While progress on issues related to joint development of resources in the East China Sea and resolution of the adulterated gyoza case remained noticeably lacking, public opinion polls suggested an upward trend in the way both Japanese and Chinese viewed each other and the bilateral relationship.

Japan - China

July — September 2009Old Issues Greet a New Government

After months of anticipation, Prime Minister Aso Taro dissolved the Diet on July 21 and scheduled elections for the Lower House. On Aug. 30, Aso’s Liberal Democratic Party suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of the Democratic Party of Japan and DPJ President Hatoyama Yukio became prime minister on Sept. 16. With Japan focused on the historic shift of power for most of the quarter, politics took primacy over diplomacy. In this environment, Japan-China relations continued to tread water, waiting for the arrival of a new government in Tokyo. Perhaps the good news is that there were no major dilemmas or disruptions and the new Japanese leadership had early opportunities to establish a relationship with their Chinese counterparts.

Japan - China

April — June 2009High-level Meetings Intensify as Old Problems Simmer

Intensive high-level meetings marked the second quarter of the year for Japan and China. In April alone, Prime Minister Aso Taro met three times with China’s leaders, President Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao. Efforts to structure a response to North Korea’s April 5 missile test and May 25 nuclear test dominated bilateral diplomacy. Japan’s call for a strong response in the UN Security Council met with Chinese appeals for caution and restraint. Japanese efforts to begin implementation of the June 2008 agreement on the joint development of natural gas fields in the East China Sea and to resolve the January 2008 contaminated gyoza cases made little progress. Issues of history were rekindled by Prime Minister Aso’s offerings at the Yasukuni Shrine and the release of movies on the Nanjing Massacre in China. The quarter ended with senior diplomats again discussing implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 1874, which imposed sanctions on North Korea.

Japan - China

January — March 2009New Year, Old Problems

The year 2008 ended with reports that China would begin construction of two conventionally powered aircraft carriers, while February brought news that China was planning to construct two nuclear-powered carriers. January marked the first anniversary of the contaminated gyoza controversy and despite concerted efforts to find the source of the contamination and the interrogation of several suspects, Chinese officials reported that the investigation was back at square one. Meanwhile, efforts to implement the June 2008 Japan-China joint agreement on the development of natural gas fields in the East China Sea made little progress and the long-standing territorial dispute over the Senkaku Islands found its way into the headlines following Prime Minister Aso’s February visit to Washington. In mid-March, China’s defense minister confirmed to his Japanese counterpart Beijing’s decision to initiate aircraft carrier construction.

Japan - China

October — December 2008Gyoza, Beans, and Aircraft Carriers

In early December, the Japanese Foreign Ministry released its annual survey of public opinion on Japan’s international relations, which revealed that over 70 percent of the public considered relations with China to be in poor shape. The survey likewise revealed a record high, 66.6 percent of the Japanese public, as feeling no affinity toward China. Meanwhile, the Ministry of Defense reported increasing PLA naval activities in the waters around Japan, including the incursion of research ships into Japanese territorial waters in the Senkaku Islands chain. There were also reports that China would begin the construction of two aircraft carriers in 2009. Japanese and Chinese leaders met in Beijing in October and in Japan in December, but beyond commitments of best efforts, failed to make any demonstrable progress on food safety and sovereignty issues.

Japan - China

July — September 2008The Gyoza Caper: Part II

The issue of contaminated frozen gyoza moved to the bilateral front burner during the quarter. In his meeting with President Hu Jintao on the sidelines of the G8 summit at Lake Toya, Hokkaido and again during the opening ceremonies of the Beijing Olympics, Prime Minster Fukuda Yasuo emphasized the importance of making progress on the six-month old case. Hu promised to accelerate efforts to identify the source of the problem and in mid-September, Japanese media reported that Chinese authorities had detained nine suspects at the Tianyang factory. The commemoration of the end of World War II on Aug. 15 passed quietly with only three Cabinet ministers visiting the Yasukuni Shrine. Meanwhile, joint Japanese and Chinese public opinion polling data revealed markedly different perceptions on the state and future course of the bilateral relationship. In early September, Japan’s Ministry of Defense released its Defense White Paper 2008, which again expressed concerns about China’s military modernization and its lack of transparency. Later in the month, the Maritime Self-Defense Force sighted what was believed to be an unidentified submarine in Japanese territorial waters. Reacting to Japanese media speculation, China’s Foreign Ministry denied that the submarine belonged to China’s Navy.

Japan - China

March — June 2008Progress in Building a Strategic Relationship

Two events dominated the second quarter of 2008: the visit of President Hu Jintao to Japan and the Sichuan earthquake. Tibet, poisoned gyoza, and the East China Sea dispute set the pre-summit agenda. Although the summit itself failed to provide solutions, both Hu and Prime Minister Fukuda Yasuo renewed commitments to cooperate in resolving the issues, and a month later the two governments announced agreement on a plan for joint development in the East China Sea. Shortly after Hu’s return to China, a devastating earthquake hit Sichuan Province. Japan’s response, which included sending emergency rescue and medical teams, tents, and emergency supplies, was well received by the Chinese victims. Beijing, however, quickly pulled back from an early but unofficial acceptance of Japan’s Air Self- Defense Force participation in relief operations. By the end of May, Japan’s contributions to relief efforts totaled 1 billion yen.

Japan - China

January — March 2008All about Gyoza: Almost all the Time

While Japanese and Chinese political leaders and diplomats worked to build the mutually beneficial strategic relationship and to advance the spring visit of China’s President Hu Jintao, both sides found it hard going. The safety of imported Chinese gyoza (dumplings) became a major issue as reports of food poisoning of Japanese became front-page news in early February. Responsibility for the poisoning, whether the result of the manufacturing process in China or deliberate action by individuals after the gyoza left the factory, became the center of contention. Health Ministry and pubic safety officials in both countries pledged cooperation in resolving the issue but failed to identify the cause, while retreating to positions that attributed responsibility to the other side.

At the same time, expectations for a resolution of the East China Sea dispute before the Hu visit, raised during the visit by Prime Minister Fukuda Yasuo to China in December, faded. By mid-March, both sides were taking the position that resolution should not be linked to a previously anticipated April cherry-blossom visit. Scheduling problems, failure to resolve the East China Sea dispute, and the gyoza controversy, combined to push the visit back to an early May, post-Golden Week time frame.

Japan - China

October — December 2007Politics in Command: Part 2

Beijing welcomed the new Fukuda government and Japan’s new prime minister made clear his commitment to improving Japan’s relations with its Asian neighbors and building the strategic relationship with China. However, the new government in Tokyo soon became preoccupied with the passage of a new antiterrorism special measures law to reauthorize Japan’s refueling operations in support of UN operations in Afghanistan, Defense Ministry scandals, and the continuing pension fund imbroglio.

Despite repeated commitments by political leadership in Tokyo and Beijing to joint development of the oil and natural gas resources in the East China Sea, there is no tangible resolution of the issue in sight. At the end of the year, joint development remained an aspiration. Even as the prime minister prepared for his late December visit to China, government and diplomatic sources were downplaying expectations that the visit would produce agreement on the issue. Meanwhile, as underscored by the first meeting of the Japan-China High Level Economic Dialogue, economic and business ties continued to strengthen the foundation of the bilateral relationship.

Japan - China

June — September 2007Politics in Command

As the second half of 2007 began, Japan focused on the Upper House election held July 29. Beset by political scandals and dogged by questions of competency, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) suffered a historic defeat. Following the election, Prime Minister Abe Shinzo was preoccupied with a Cabinet reshuffle that resulted in the appointment of Machimura Nobutaka as foreign minister and Komura Masahiko as minister of defense. At the same time, the government was preoccupied with preparations for the Japan-North Korea Working Group meetings as the Six-Party Talks appeared to gather momentum. Meanwhile, Beijing worked to accentuate the positive, the approaching anniversary of the normalization of Japan-China relations (1972) and to downplay history, the July anniversary of the Marco Polo Bridge Incident (1937).

The tempo in the bilateral relationship began to pick up with the late August visit to Japan of China’s minister of defense and the early September meetings between Prime Minister Abe and President Hu Jintao on the sidelines of the APEC meeting in Sydney. On Sept. 12, Abe announced his resignation. Beijing’s reaction was to make clear the importance China places on the development of a stable bilateral relationship. On Sept. 25 Beijing congratulated Prime Minister Fukuda Yasuo on his accession to office and expressed hope that the reciprocal strategic relationship would continue to develop in a healthy and stable manner.

Japan - China

March — June 2007Wen in Japan: Ice Melting But . . .

The April 11-13 visit of China’s Premier Wen Jiabao proved to be a public diplomacy success. Wen met with Prime Minster Abe, and, focusing on environmental cooperation, both leaders agreed to advance their strategic relationship. Wen addressed the Diet, a historic first; engaged early morning Tokyo joggers in conversation; and played catch with the Ritsumeikan University baseball team in Kyoto. Before his departure, Wen made clear that he considered his visit a success in strengthening bilateral relations. And, judging from the attention given to a mid-June meeting between President Hu Jintao and former Prime Minister Nakasone and members of the Japan-China Youth Friendship Association, so did his boss. In the run-up to the September Party Congress, the media suggested that Hu was running on a platform of improving relations with Japan. Success at public diplomacy, however, did not translate into success at the nuts and bolts level. Despite repeated high-level commitments to a resolution of the East China Sea issue, little progress was evident as the quarter drew to a close. And testing times, the 70th anniversary of the Marco Polo Bridge Incident in July and the 70th anniversary of the Nanjing Massacre in December loom on the horizon.

Japan - China

April — June 2007Treading Water, Little Progress

Although progress was made in resolving the Banco Delta Asia dispute between North Korea and the United States, and international inspectors were invited back into North Korea in June, relations between Japan and North Korea remain deadlocked, with no apparent progress or even political will to address the deep issues that divide them. Seoul and Tokyo made little progress on their history issues. However, the meeting of the foreign ministers of China, Japan, and South Korea this quarter was a positive step, and with elections coming up in Japan and South Korea, the prospect of further foreign policy changes appears likely.

Japan - China

January — March 2007New Year, Old Problems, Hope for Wen

Japanese and Chinese political leaders and diplomats, focusing on the steps necessary to build a strategic mutually beneficial relationship, worked throughout the quarter to lay the groundwork for a successful April visit to Japan by Premier Wen Jiabao. Dialogue, cooperation, and peaceful resolution were omnipresent bywords. But, in fact, little progress was made in addressing longstanding issues related to the East China Sea, North Korea, security, and China’s Jan. 11 anti-satellite (ASAT) test – all hopefully deferred for resolution to the Wen visit. Meanwhile, Prime Minister Abe Shinzo and the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) were caught up in a debate over history, comfort women, and Nanjing. Interestingly, Beijing’s response was low key, suggesting a commitment on the part of China’s leadership to progress with Japan.

Japan - China

October — December 2006Ice Breaks at the Summit

The long search for a Japan-China Summit was realized Oct. 8, when Japan’s new Prime Minister Abe Shinzo arrived in Beijing and met China’s President Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao. Abe and Hu agreed to build a “strategic, reciprocal relationship” aimed at enhancing cooperation and advancing a wide range of mutual interests. Both leaders agreed to address the difficult issues of history and the East China Sea, setting up expert panels to explore ways to resolve them. On the topic of visiting Yasukuni Shrine, Abe relied on strategic ambiguity, which the Chinese leadership appeared to tolerate, if not accept, in the interest of moving relations ahead. The joint history panel met in Beijing at the end of December and the East China Sea experts meeting was scheduled for early in the new year. After several years of tough going, the road ahead appears smoother and more promising.

Japan - China

July — September 2006Searching for a Summit

Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro visited Yasukuni on Aug. 15, honoring a long-standing campaign pledge. China protested the visit and moved on, focusing its attention on Chief Cabinet Secretary Abe Shinzo, odds-on favorite to succeed Koizumi as Liberal Democratic Party president and Japan’s prime minister. Abe took the reins of the LDP Sept. 20 and control of the government Sept. 26. China welcomed Abe with the same words it welcomed Taiwan’s President Chen Shui-bian: it would listen to what he says and watch what he does.

Meanwhile in Japan, the late Showa Emperor and the LDP’s intra-party search for a successor brought the subject of Japan’s relations with its neighbors and the nature of Yasukuni Shrine to center stage. In August, Abe acknowledged an April visit to the shrine but, contrary to his custom of visiting the shrine on Aug. 15, did not do so this year. Even before taking office, Abe made clear his interest in finding a path to a summit meeting with China. As the fourth quarter begins, Japanese and Chinese diplomats are engaged in exploring various paths to a summit.

Japan - China

April — June 2006Spring Thaw

For the first time in over a year, the foreign ministers of Japan and China met on May 23. Both ministers retreated to well-worn talking points on Yasukuni but agreed to move ahead in expanding exchange programs. Afterward, Foreign Minister Aso Taro announced that Japan’s relations with China were moving toward normalcy and in early June, to further warm the atmosphere, the Koizumi government removed the freeze on loans to China. In turn, China’s President Hu suggested that under the proper conditions and at an appropriate time, he would like to visit Japan.

The vice ministers of foreign affairs also met in Beijing to conduct the Fifth Japan-China Comprehensive Policy Dialogue. Meanwhile, director general-level discussions continued on the East China Sea. Beyond a desire to keep talking, little progress was evident.

In Japan, political leaders jockeyed for position in the post-Koizumi prime ministerial sweepstakes. Increasingly, foreign policy, Japan’s relations with its Asian neighbors, and Yasukuni-related matters assume growing importance in the political debate, with candidates attempting to find their footing on the issues. In meetings with Japanese political figures, China’s political leaders and diplomats worked to shape the post-Koizumi environment in Japan.

Japan - China

January — March 2006Looking Beyond Koizumi

The quarter ended as it began – with Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro expressing his inability to understand why China and the Republic of Korea refused to hold summit meetings just because of differences over Yasukuni Shrine. He also could not understand why he should not pay homage at the shrine simply because China and South Korea said he should not do so. Meanwhile, China’s leadership made clear that it was writing off the next six months and looking to a post-Koizumi future. During the quarter, Beijing hosted a number of high-level political delegations and courted potential Koizumi successors. Reflecting the political stalemate, diplomatic efforts to resolve issues related to the exploration and development of natural gas fields in the East China Sea failed to make progress. China rejected Japan’s proposal for joint development, and when Chinese diplomats presented their ideas, Japanese diplomats found little they could agree to beyond agreeing to take them back to Tokyo, where the political reception proved decidedly frosty.

Despite the government adopting the position that China was not a threat to Japan, the political debate continued. The opposition Democratic Party of Japan adopted a party platform that China represented an “actual threat” to Japan. At the end of March, the Foreign Ministry released the 2006 Diplomatic Blue Book, which called attention to the lack of transparency in China’s military budget and in the modernization of the People’s Liberation Army. In the face of “cold politics,” economic relations continued “hot.” For the seventh consecutive year, Japan’s trade with China hit a record high in 2005, reaching $189.3 billion.

Japan - China

October — December 2005Yasukuni Stops Everything

Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro’s Oct. 17 visit to the Yasukuni Shrine effectively put Japan-China relations into a political deep freeze. Meetings on sensitive East China Sea issues were cancelled and prospects for a Japan-China leadership summit before the end of the year went from slim to none. In December, Foreign Minister Aso Taro and Democratic Party of Japan President Maehara Seiji raised the issue of a China threat, which Beijing dismissed as irresponsible and without foundation. China’s diplomatic White Paper, issued at the end of December, announced that China has never been a threat and that it never had and never would seek hegemony.

Japan - China

July — September 2005Summer Calm

During this quarter, China observed a number of anniversaries in Sino-Japanese relations related to the Japanese military action in Asia. China’s leadership took care that the anniversaries, aimed at strengthening Chinese patriotism and the legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), would not replicate the anti-Japanese sentiment loosed in April. And they were successful.

At the same time in Japan, domestic politics were center stage. Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro was absorbed in the passage of his postal reform legislation. Failure to secure passage led Koizumi to dissolve the Diet in early August and to go to the polls Sept. 11. The prime minister focused his campaign on the reform issue and avoided discussion of Aug. 15 and his visits to the Yasukuni Shrine. Meanwhile, Japanese diplomacy is absorbed by the Six-Party Talks.

One issue did disturb the political and diplomatic calm – the East China Sea territorial dispute. In July, the Japanese government granted exploration rights to Teikoku Oil Company in the area east of the mid-line boundary, which China has refused to acknowledge. The government later committed to protect Teikoku exploration activities in the event of Chinese challenges. In mid-September, reports reached Tokyo that China had initiated natural gas production in the Tianwaitian field – on the western Chinese side of the mid-line. Diplomats are scheduled to meet in Tokyo at the end of September to discuss East China Sea issues.

Japan - China

April — June 2005No End to History

From the April anti-Japanese riots through Vice Premier Wu Yi’s snubbing of Koizumi and the June debates over Yasukuni and China policy within the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and governing coalition, history demonstrated its power over the Japan-China relationship. The past influenced the present and future as sovereignty issues over the Senkaku islands and East China Sea were caught up in surging nationalisms in both countries. The Japanese prime minister’s visits to the Yasukuni Shrine to pay homage to Japan’s war dead touched almost every aspect of the relationship, including Japan’s official development assistance (ODA) program. Even traditionally robust commercial and economic ties wobbled. History punctuated the end of the quarter as well, when, at the end of June, three Chinese residents of Guangzhou city were afflicted by poison gas leaking from shells abandoned by the Japanese Imperial Army and Chinese authorities in Dalian confiscated Japanese textbooks intended for use in the local Japanese school for inappropriate references to Taiwan.

Japan - China

January — March 2005Trying to Get Beyond Yasukuni

The New Year opened with promise – Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro did not visit the Yasukuni Shrine. While old issues, history and nationalism, sovereignty in the Senkaku (Diaoyu) Islands and the East China Sea, the extent and scope of the Japan-U.S. alliance (Taiwan) lingered, if not intensified, political leaders and diplomats worked to repair strained political relations, hopefully setting the stage for high-level reciprocal visits. The spirit of the Santiago and Vientiane Summits, in particular dealing “appropriately” with the Yasukuni issue, appeared to suffuse political and diplomatic engagement. Meanwhile, economic relations continued to expand – China replaced the United States as Japan’s top trading partner in 2004.

Japan - China

October — December 2004A Volatile Mix: Natural Gas, a Submarine, a Shrine, and a Visa

The dispute over exploration of natural gas fields in the East China Sea continued to simmer. China proposed working-level discussions and the two sides met in Beijing. The results left Japanese officials wondering why they bothered to attend. Shortly thereafter, Japanese patrol aircraft tracked a Chinese nuclear submarine traveling submerged through Japanese territorial waters. Beijing’s apology paved the way for summit-level talks between Japanese Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro and China’s President Hu Jintao and later Premier Wen Jiabao. The talks only highlighted issues of Yasukuni Shrine and history in the bilateral relationship, underscoring national sensitivities in both countries. In Japan, reaction centered on graduating China from Japan’s ODA program; this was not appreciated in Beijing. In the meantime, Tokyo issued Japan’s new National Defense Program Guidelines, which highlighted China’s military modernization and increasing naval activities, concerns which Beijing found groundless. Finally, Japan approved a visa for Taiwan’s former President Lee Teng-hui, in Beijing’s eyes a “splittist” and advocate of Taiwanese independence.

Also during the quarter, commercial and economic relations continued to expand. The phenomenon of bifurcated political and economic relations with China is now characterized in Japan as “cold politics; hot economics.” An end of year Asahi Shimbun editorial asked: “can this be resolved?”

Japan - China

June — September 2004Not The Best Of Times

Both Tokyo and Beijing looked for ways to advance cooperation this quarter. The ASEAN Plus Three framework provided one venue. North Korea provided another. Commercial and economic relations provided a third: two-way trade in the first six months of 2004, for the fifth consecutive year, hit a new high.

But a series of events, such as resource exploration in disputed areas in the East China Sea, Chinese maritime research activities in Japan’s claimed Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), significant anniversaries – the Marco Polo Bridge Incident (July 7), Aug. 15 visits by Japan’s political leaders to the Yasukuni Shrine, the Mukden Incident, (Sept. 18) –combined with Japan’s 3-1 victory over China in the China-hosted Asia Cup soccer tournament to keep nationalist emotions at a high state in both countries. Other issues of history, munitions abandoned by the Imperial Army in China, court decisions on compensation claims for wartime forced labor, and Taiwan also played into the relationship. It was not the best of times.

Japan - China

March — June 2004Not Quite All about Sovereignty – But Close

Issues related to sovereignty dominated the Japan-China political and diplomatic agenda. As the quarter began, politicians and diplomats were involved in the controversy generated by the landings of Chinese activists on Uotsuri Island in the Senkaku/Diaoyu Island chain. The quarter ended with politicians and diplomats dealing with Chinese efforts to test drill for natural gas in the East China Sea bordering the Japan-China demarcation. Tokyo was concerned that extraction could tap resources on the Japanese side of the demarcation line. In the interim, the issue of Chinese maritime research ships operating, without prior notification, in Japan’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) kept the political-diplomatic spotlight focused on sovereignty claims.

At the same time, issues of history repeatedly surfaced. In April, the Fukuoka District Court ruled that Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro’s visits to the Yasukuni Shrine were tantamount to religious activity and violated the constitution. However, in May, the Osaka District Court, while not addressing the constitutional issue, found the visits to be private in nature, not the official action of a government officer. In either case, the prime minister made clear that he would continue to visit the shrine, and his foreign minister returned from China again without the prime minister’s long-sought invitation for an official visit to China. In northeast China, chemical weapons abandoned by the Imperial Army again affected Chinese construction workers in Qiqihar.

Japan - China

January — March 2004Dialogue of the Almost Deaf

It was not quite all Yasukuni all the time, but close. Set off by Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro’s Jan. 1 visit to the shrine, Yasukuni served as the leitmotif for extensive high-level political and diplomatic exchanges over the first quarter of the year. Neither the prime minister and his political proxies nor China’s political leaders gave any ground. As the quarter ended, Koizumi, determined to continue his visits to the shrine, seem resigned to not visiting China if the Chinese did not want him to visit, while the Chinese made it clear that Yasukuni was the problem.

In the meantime, the Self-Defense Forces deployed to Iraq, raising back-to-the-future concerns in Beijing, and a landing by Chinese activists on the Senkaku Islands at the end of March raised nationalist sentiments in both countries. In Japan, suits brought by Chinese nationals seeking compensation for wartime forced labor kept alive the issues of history. At the end of March, for the first time, the Niigata District Court ruled in favor of Chinese plaintiffs in a case brought against both the Japanese government and a private company.

The good news, as both Koizumi and Chinese Prime Minister Wen Jiabao agreed, was economic. Commercial relations rapidly expanded during the quarter, stimulating Japanese growth rates. As a result, Japanese views of China were shifting from “threat” to “market opportunity” as China’s consumers continued to consume made-in-Japan electronics and machine products.

Japan - China

October — December 2003Cross Currents

In October, Japanese Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro met with China’s Premier Wen Jiabao and President Hu Jintao. On each occasion, the leaders renewed commitments to enhance cooperation in the bilateral relationship, and, at the leadership level, cooperation – on North Korea, energy, banking and finance, and conservation – defined the relationship over the final quarter of the year. China’s leaders, however, made clear that a proper understanding of history is central to the development of bilateral relations.

Economic and financial relations continued to expand and diversify, almost on a daily basis. But Japan’s rapidly expanding private sector presence on the mainland had to deal with Chinese national sensitivities and the burdens of history. In one instance, Toyota had to pull an advertisement for its SUV in response to a groundswell of Chinese protests and internet threats of a boycott.

Meanwhile, the repercussions of a Fukuoka murder committed by Chinese students; of the September Zhuhai sex orgy involving a Japanese business tour group; and of a Chinese rampage at Xian’s Northwest China University following a dance performed by Japanese students resurfaced nationalist sentiments in both countries. At the same time, the August Qiqihar chemical weapons incident and a series of compensation cases brought in Japanese courts by Chinese survivors of wartime forced labor kept history in the forefront of the relationship.

Japan - China

July — September 2003Bridges to the Future, Reflections on the Past

In anticipation of the 25th anniversary of the Japan-China Friendship Treaty, both Tokyo and Beijing worked to normalize political relations. Japan’s chief Cabinet secretary and defense minister traveled to China, while China’s foreign minister and the chairman of China’s National People’s Congress visited Japan. But, at the end of the comings and goings, Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro had yet to secure the long-coveted invitation for an official visit to China.

Aug. 15 brought with it the customary end of war remembrances as well as lectures about history and its proper understanding. History did, however, intrude on 21st century reality, as the unearthing of chemical weapons abandoned by the Imperial Army in northern China led to the hospitalization of over 30 construction workers and the death of one. The Koizumi government moved quickly to deal with the issue, offering “sympathy” compensation to the families affected.

Meanwhile, economic relations continued to expand. Two-way trade skyrocketed during the first half of the year, even as the SARS epidemic raged during the second quarter. By mid-July, most Japanese companies in China were operating on a “business as usual basis.” At the same time, domestic economic pressures were building in Japan to push the Koizumi government to seek a revaluation of China’s currency.

Japan - China

April — June 2003Political Breakthrough and the SARS Outbreak

Political relations broke out of the Yasukuni-induced deep freeze. Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro met with China’s President Hu Jintao in St. Petersburg, Russia, on May 31 during ceremonies marking the city’s 300th anniversary. Less than three weeks later, during meetings of the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) in Phnom Penh, Foreign Minister Kawaguchi Yoriko invited China’s new Foreign Minister Li Zhaoxing to visit Japan in August to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the Japan-China Friendship Treaty; Li accepted. Japan also successfully lobbied China to support Japan’s admission to the multilateral U.S.-China-North Korea talks that opened in April in Beijing.

But across the board, the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic in China dominated the relationship. Japan extended emergency medical assistance and personnel to help China cope with the epidemic. SARS also affected Japanese business operations in China as well as in Japan, which is now increasingly dependent on low-cost component imports from China. Throughout the quarter, economists repeatedly tried to assess the bottom-line impact of SARS. Through mid-May, the prospects were judged to range from bad to catastrophic. However, by the end of the quarter as the epidemic appeared to come under control, economic forecasts brightened.

Japan - China

January — March 2003Cross Currents

The new year began with controversy. Territorial issues over the Senkaku/Daoyutai Islands resurfaced at the beginning of January and Japanese Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro’s visit to the Yasukuni Shrine followed in short order. Political reaction in Beijing to the Yasukuni visit again derailed planning for a Koizumi visit to China and also affected Japan’s diplomacy toward North Korea, complicating efforts to secure Beijing’s cooperation in dealing with Pyongyang’s nuclear program.

Nevertheless, the two governments demonstrated an ability to work through practical problems posed by North Korean refugees in China (some Japanese nationals) seeking asylum in Japan. At the same time, economic relations continued to broaden and deepen. For the first time, Japan imported more from China than from the U.S., while Japanese exports to China increased 32 percent in 2002. And, with a new leadership coming to power in Beijing, there were signs of new thinking with respect to Japan and history.

Japan - China

October — December 2002Congratulations, Concern, Competition, and Cooperation

The quarter began with celebrations commemorating the 30th anniversary of the normalization of relations. But, during the last quarter of 2002, Japan’s relations with China played second fiddle to relations with North Korea, and, after Oct. 3, the nuclear crisis emerging on the Korean Peninsula.

Though not in Beijing to attend 30th anniversary celebrations, Japanese Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro did meet with Chinese President Jiang Zemin at the end of October and Premier Zhu Rongji at the beginning of November. Issues of the past, exemplified by the prime minister’s visit to the Yasukuni Shrine, and the future, North Korea and free trade agreements, dominated the discussions. However, even as the leaders met to advance cooperation, public opinion surveys in Japan and China pointed to problems ahead in the relationship.

Nevertheless, China’s new leaders, announced formally during the November People’s Party Congress, were favorably evaluated in Japan, in part as being less consumed with the issues of history. In what many in Japan saw as a goodwill gesture aimed at getting off to a good start with the new leadership, Tokyo moved quickly to resolve sensitive issues involving Taiwan’s former President Lee Teng-hui and the activities of a Japanese military attaché in China.

China’s concerns over Japan’s surging steel exports caused Beijing to impose formal safeguards on five kinds of steel imported from Japan. At the same time, commercial relations continued to broaden and deepen, with surveys indicating Japanese companies focusing on China as the market of the future.

Japan - China

July — September 2002Toward the 30th Anniversary

The quarter ended on a high note with ceremonies in Beijing commemorating the 30th anniversary of the normalization of relations between Japan and China. Senior Foreign Ministry officials and over 50 political figures represented Japan. Conspicuously absent, however, was the prime minister. Still under a Chinese cloud for his April visit to Yasukuni Shrine, Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro decided in August not to attend the ceremonies.

Over the course of the summer the past continued to intrude on the present. A Tokyo District Court was the first to rule that Japan had engaged in biological warfare in China during the war. The court, however, rejected the Chinese plaintiffs suit for compensation. Visits by members of the Koizumi Cabinet to Yasukuni Shrine on Aug. 15 drew traditional censure from Beijing. At the same time, Japanese concerns with China’s on-going military modernization and its perceived lack of gratitude for Japan’s development assistance largess foreshadowed a looming debate over the China official development assistance (ODA) program.

Nevertheless, commerce continued to expand as joint ventures multiplied, and Japanese investment continued to flow into China (although at reduced rates). At the same time, the safety of Chinese dietary supplements and pesticide residue on imported Chinese vegetables have triggered trade controversies.

Japan - China

April — June 2002The Good, the Bad, and … Japan-China Relations