Articles

2018 came to a relatively quiet close for the US and Japan. Prime Minister Abe Shinzo secured a third term as leader of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) in a party election on Sept. 20 and is now set to be Japan’s longest serving prime minister. In contrast, President Donald Trump faced an electoral setback in the November midterms. With Democrats taking over the House of Representatives in January, pressure on the administration will grow. In December, Trump dismissed Chief of Staff John Kelly and Defense Secretary James Mattis, and locked horns with the incoming Democratic Party leadership over funding for his border wall. Nevertheless, the US-Japan relationship seemed steady. In September, Prime Minister Abe agreed to open bilateral trade talks and in return sidestepped the Trump administration’s looming auto tariffs. Yet there are differences over their goals, suggesting that continued compromise will be needed. Abe worked hard in numerous summits to position Japan in Asia in the final months of 2018. He visited China, hosted India’s prime minister in Tokyo, and restarted the negotiations with Russia on the northern territories. Japan also announced its next long term defense plan and a five-year, $240 billion implementing procurement plan that includes a considerable investment in modern US weapon systems.

Toward a trade agreement (on goods)

At their summit in September, Trump and Abe agreed to enter into negotiations on a Japan-US trade agreement on goods, or TAG. The joint statement from the summit seemed to offer a quick diplomatic victory for both leaders. Trump could claim credit for bringing Japan to the negotiating table after months of Japanese officials insisting that they were not interested in bilateral talks. Instead, Abe’s trade team had tried repeatedly to convince Trump to rejoin the multilateral Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP, or TPP-11), an agreement from which Trump withdrew the US just days into his presidency. For Abe, agreeing to begin talks earned Japan at least a temporary reprieve from Trump’s threatened 20 percent tariff on automobiles. which reports suggest would have increased manufacturing costs by $8.6 billion, decreased car exports by 200,000 units, and cut profits by 2.2 percent. Moreover, Abe got the US to accept that Japan would not go any further than the CPTPP in opening up its agricultural and forestry markets.

Agreeing to begin TAG talks is, of course, just the first step in a long process. While Japan has drawn a line in the sand on agriculture, automobiles will be front and center in the coming negotiations. Trump has repeatedly stated that his goal is to reduce the US trade deficit and improve access to the Japanese automobile market for US car manufacturers. Automobiles and auto parts make up about 75 percent of the trade deficit with Japan, which at $68.85 billion (2017) is the third largest for the US after its deficit with China and Mexico.

US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer and Japanese Economic and Fiscal Policy Minister Motegi Toshimitsu are set to lead the first round of TAG negotiations in early 2019, but for now there is a divide between the two sides on what topics will be covered in the talks. Abe and senior Japanese officials have consistently stated that they are only interested in a trade agreement on goods. In contrast, US officials want to pursue a much more comprehensive free trade agreement. On Dec. 21, the US Trade Representative (USTR) released a summary of 22 specific negotiating objectives for the talks, covering a wide range of services (e.g., financial, telecommunications, pharmaceutical), regulatory practices, intellectual property, and investment, as well as a provision to prevent currency devaluations.

The Trump administration’s desire for a more comprehensive agreement may come into conflict not only with their Japanese counterparts, but also with domestic industries that are hoping for a speedy resolution to negotiations. At a USTR public hearing for the trade talks on Dec. 10, representatives from several major US beef associations urged officials to reach a deal quickly with Japan as they are worried about being left behind after the CPTPP comes into effect. Under the CPTPP, Japan has agreed to gradually reduce its 38.5 percent tariff on beef imports to 9 percent over the next 16 years for US competitors such as Australia, New Zealand, and Canada that are party to the deal.

As US-Japan trade talks get underway in the new year, Japanese officials will also be paying close attention to how the US handles trade frictions with other partners, particularly China. President Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping agreed to a 90-day ceasefire in their trade war at their meeting at the G20 Summit in Argentina. However, this does not leave much time to iron out their many differences on trade. The Trump administration could still raise tariffs from 10 to 25 percent on $200 billion worth of imports from China, or even increase the tariffs to cover all $500 billion of imported goods. The tariffs could have a significantly negative impact on Chinese economic growth, raising US consumer prices and sending inflationary shockwaves through Asia. One recent estimate by a former Bank of Japan policy board member found that a US-China trade war could shrink the value of world trade by 2 percent and reduce Japan’s GDP by 0.6 percent.

Apart from China, the US will also be busy in 2019 as Trump continues his efforts to revise the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). After months of bitter negotiations, the United States, Canada, and Mexico reached an agreement on Sept. 30 and signed the new deal two months later on Nov. 30. Now Trump must seek congressional approval, which will become much more challenging after Democrats assume control of the House in January. On Dec. 2, Trump threatened to withdraw from NAFTA, a move meant to force House Democrats to approve his revised version. If Trump follows through on the threat, Congress will have just six months to pass the new NAFTA; otherwise, it will risk causing significant harm to industries across all three countries by allowing NAFTA to expire.

In Japan, Abe will be looking to continue the momentum he built in 2018, which marked a year of significant progress on several free trade agreements, from signing and ratifying the CPTPP to inking an even larger trade deal with the European Union. The CPTPP officially entered into force on Dec. 30 for the first six countries to ratify the deal: Japan, Australia, Canada, Mexico, New Zealand, and Singapore. It will enter into force on Jan. 14 for Vietnam, and for Brunei, Chile, Malaysia, and Peru 60 days after they complete their domestic ratification processes. Even without the US, the deal still covers more than 13 percent of the global economy and $10 trillion in GDP. Abe may be hoping to continue his success streak in negotiations with the US, but any new trade deals will have to compete with a busy political calendar in 2019, including local elections in April, Upper House elections in July, and a planned consumption tax increase from 8 to 10 percent in October.

U.S. Midterms, a divided Congress, and a beleaguered White House

The final months of 2018 produced a far more difficult political path ahead for President Trump. The midterm elections in November resulted in a steady wave of Democratic victories in the House of Representatives, but the Republicans held their majority in the Senate. The new House leadership is expected to scrutinize the president far more intensely than did their Republican predecessors. With the Intelligence, Judiciary, and Oversight Committees now all chaired by Democrats who have signaled interest in a more careful look at the links between private business interests and the Trump administration’s decisions, expectations are that the White House will be under intense pressure to respond to multiple sources of congressional inquiry. Of particular interest are the Trump Organization’s business relations with Russian banks and his family’s decisionmaking in running his businesses since he assumed the presidency, but Trump administration Cabinet officials are also suspected of using their offices to their personal advantage.

A divided Congress is not all the White House will have to manage, however. Legal challenges are likely to consume the attention of the president and his advisors. Lawsuits investigating the Trump family’s management of his business while the president has been in office are now ongoing in multiple states. And, of course, the Justice Department’s Special Counsel investigation of the Trump campaign and its ties to Russia has produced multiple indictments of senior campaign staff. In the fall, former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort, former Trump lawyer, Michael Cohen, and former White House national security adviser, Lt. Gen. Michael Flynn, were all in federal court for their criminal conduct during the campaign and the subsequent FBI investigation. Special Counsel Robert Mueller is expected to release his investigation’s final report in 2019, but trials for some of those indicted by the Justice Department investigation will continue in the Southern District of New York.

Setting the tone for this increasingly fraught Washington was the government shutdown in the final days of 2018. In a televised meeting at the White House, President Trump locked horns with incoming House majority leader Nancy Pelosi and Senate minority leader Chuck Schumer over funding of the southern border wall. By the new year, President Trump was threatening to keep the government closed for “months or even years” if need be, while Pelosi also stood firm, offering a new budget deal that included funding for border security but not the $5 billion the president wanted for his wall. 800,000 federal workers have been furloughed or are working without pay, and if the shutdown continues past Jan. 21, many more federal agencies will be affected.

President Trump’s foreign policy decisions are becoming far more unpredictable. The president’s abrupt announcement that US forces would be withdrawn from Syria and cut in Afghanistan, announced without preparation or internal consensus, has raised red flags about the reliability of US support to allies. Secretary of Defense Mattis resigned in protest on Dec. 20, and in his public resignation letter, Mattis made clear that it was over the treatment of US allies.

Abe’s major power diplomacy

The fall of 2018 was a busy time for Prime Minister Abe with multiple summits with other Asian leaders. From Oct. 25-27, Abe visited China to meet President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang. Abe and Xi promised a “fresh start” for China-Japan relations. The tensions over the East China Sea seem to have waned somewhat, and the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs outlined steps the two leaders had taken to enhance crisis communications, a reminder to audiences at home and in the region that neither side wants a military conflict. Yet Beijing and Tokyo are still struggling with some sensitive issues, including differences over their maritime boundary in the East China Sea and acceptable regulatory standards for food security. A new highlight, however, was cooperation in Asia’s economic development. Specifically, Abe and Xi agreed that they would work together on infrastructure development projects. Nonetheless, each favors a different vision for Asia; Abe argued for a “free and inclusive Indo-Pacific,” while Xi continued to extol his Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). There was no joint statement from this meeting, but Xi is expected to visit Japan in 2019 as the culminating summit in this renewed effort at getting the bilateral relationship back on track.

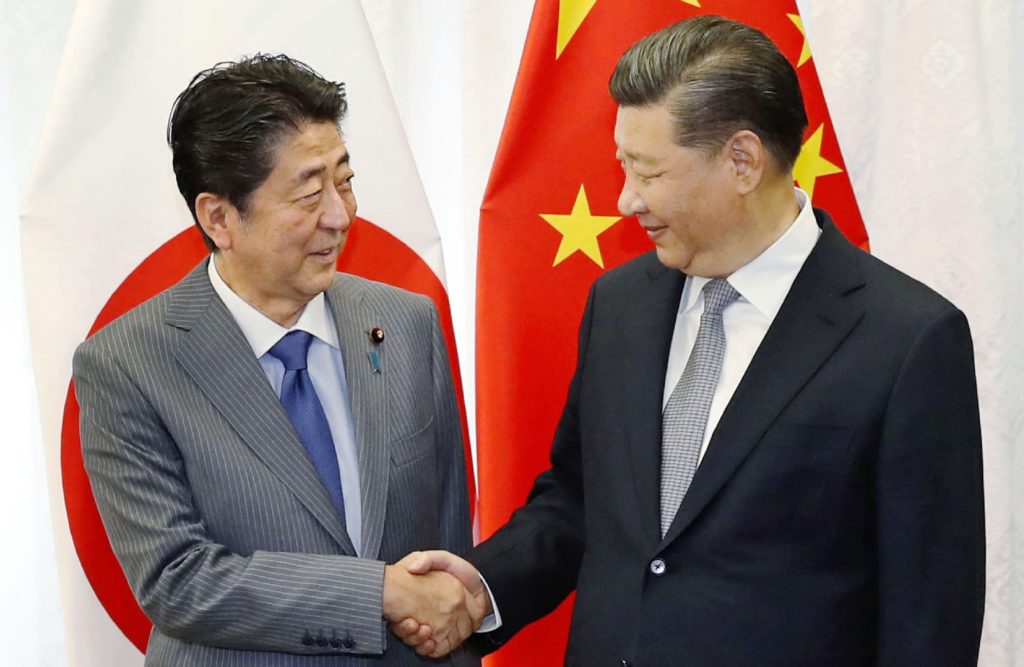

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and Chinese President Xi Jinping shake hands in Vladivostok on Sept. 12. Photo: Kyodo

The Beijing summit notwithstanding, Abe has continued to emphasize the Japan-India partnership. On the day Abe returned from China, Prime Minister Narendra Modi landed in Tokyo, demonstrating once again the close coordination between Japan and India in realizing a new Indo-Pacific framing for regional cooperation. Abe and Modi signed a Japan-India Vision Statement, marking their fourth year of ever-deeper strategic cooperation. Japanese support for Indian economic development continues to expand, including further workforce training and technology transfer opportunities as well as in creating better cooperation in the digital economy. Building on the success of the trilateral Malabar exercises with the US, Japan-India security cooperation will now include a 2+2 strategic dialogue and a new cross-servicing agreement will allow the Indian and Japanese militaries to work together more effectively with the US.

Perhaps the most overlooked of Abe’s fall summits was the meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin at the G20 meeting in Argentina on Dec. 1. Abe’s effort to persuade Putin to reach a compromise on the pathway to a peace treaty has been stymied by Russia’s reluctance to move on the sovereignty dispute over the islands Japan calls the Northern Territories and Russia refers to as the Southern Kuriles. Putin’s visit to Abe’s hometown in Yamaguchi Prefecture in 2016 proved a setback for the prime minister as Putin retreated to Moscow’s position that the only acceptable way forward was a two island solution, a reference to a 1956 joint declaration between Moscow and Tokyo to split the four islands between the two countries. On Nov. 14, Abe and Putin agreed to accelerate peace talks once again, and in Argentina they announced special envoys would conduct negotiations in the hope that another summit could be held between the two leaders in Jan. 2019. If Putin is serious about engaging Abe in his effort to finalize a peace treaty, Japan may be hard pressed to explain a warming in ties with Russia at precisely the time when US and Russian military tensions seem increasingly ominous.

Japan’s new defense plan

The Abe Cabinet’s much-anticipated new ten-year defense plan was announced in Tokyo on Dec. 18, alongside procurement plans totaling $240 billion for the first five years. Reflected in the plan were Japan’s continuing concerns over the North Korean missile threat and China’s military expansion into the East and South China Seas.

Japan’s air defenses, including missile defense, got a conspicuous boost with the purchase of two major US weapon systems, 147 F-35 fighters, and the AEGIS ashore enhanced ballistic missile defense (BMD) system. A year earlier, President Trump had urged Prime Minister Abe to buy more US weapons, and Abe seems to have made good on his promise to do so. Additionally, the Air Self-Defense Force (ASDF) will have longer-range missiles that can ensure offshore defenses. Media headlines zeroed in on one particular initiative: the Ministry of Defense’s proposal to refit the JS Izumo and other large helicopter-capable Maritime Self-Defense Force (MSDF) destroyers to accommodate the F-35B, which is capable of short take-off and landing. While no F-35Bs are to be stationed on these ships, this new platform for fighters offers the MSDF considerable flexibility in planning offshore defense operations. Finally, the Ground Self-Defense Force (GSDF) will operate the new AEGIS ashore system, bringing all three services into the BMD mission and creating the opportunity for a combined BMD command.

Modernizing Japan’s existing forces has been an ongoing goal, but this new defense plan also placed considerable emphasis on two new sets of challenges for the Self-Defense Force (SDF). The first is in readiness and combined combat operations. The language of the 2018 plan clearly signals the renewed interest in the SDF’s resilience and retaliatory capabilities. Being able to respond to attack has always been essential to deterrence, and a significant foundation of alliance readiness. SDF readiness is now at the forefront of Japanese planning, especially its ability to detect and defend offshore. The second highlight of this plan is to create capabilities in cyber, space, and defending against electromagnetic attacks. A new combined space command will be established, with input from Japan’s space agency and personnel from the SDF. Each branch of the SDF will also form new units dedicated to cyber and electronic magnetic pulse operations.

Alliance qualms as 2019 begins

At the end of 2018, several uncertainties remain on the US-Japan alliance agenda. The first will be the continued dissatisfaction in Okinawa over Tokyo’s plan to consolidate US bases there. In a special election on Sep. 30, residents elected Denny Tamaki to take the place of Gov. Onaga Takeshi, who passed away in August, and to carry on his resistance to Tokyo’s plan to build a new home for the US Marines in Henoko. The defeat of the LDP-backed candidate, Ginowan mayor Sakima Atsushi, was a serious setback for the party, and reveals its continued electoral difficulties there. Tamaki served in the Diet as a member of the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) from 2009 to 2018, so he has experience in Tokyo. As governor, Tamaki announced his intention to hold a prefecture-wide referendum as a means of conveying Okinawan sentiment to Tokyo, and once more suggesting the possibility of renewed citizen engagement in the base issue.

Okinawa Gov. Denny Tamaki speaks on Dec. 15 to a rally opposed to relocating the US military base. Photo: Kyodo

Second, trade negotiations are likely to continue to draw criticism as voters in both countries question the economic benefits of the US-Japan relationship. The governments differ on their preferences for managing trade, with the Trump administration focusing on bilateral talks and the Abe Cabinet continuing its emphasis on regional and global trade approaches. The Trump administration’s insistence on tariffs as an instrument of pressure sits uneasily among the Japanese – policymakers and citizens, alike – and the lack of consultations on steel and aluminum tariffs still stings. The threat of auto tariffs was what got Japan to the table, but two issues remain sensitive in the negotiations ahead. The first is whether the US remains committed to accepting the market access for agricultural goods negotiated bilaterally during the TPP discussions and the second is whether the limit on trade agreements with nonmarket economies in the new Canada-US-Mexico agreement will become a precedent for all US trade deals.

Finally, Japan continues to worry about unresolved tensions with North Korea and with China. The US-China trade conflict remains unresolved, and an escalation in military tensions cannot be ruled out. The Trump-Kim talks remain unproductive, although North-South diplomacy on the Korean Peninsula continues. Kim Jong Un’s New Year’s Address seemed designed to flaunt these alliance differences. Close US-Japan military coordination remains imperative, and the exit of Defense Secretary Mattis—a strong believer in US alliances—has undoubtedly unsettled Tokyo. As 2019 opens, the US-Japan relationship will continue to be managed carefully as Tokyo shores up its regional geostrategic position while it tries to wait out the increasingly difficult politics in Washington.

Sept. 20, 2018: Prime Minister Abe Shinzo wins re-election as president of the Liberal Democratic Party.

Sept. 21, 2018: Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and the US Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) sign a Memorandum of Cooperation to strengthen cooperation in financing private sector investment projects.

Sept. 21, 2018: Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Foreign Minister Kono Taro speak by telephone about North Korean denuclearization.

Sept. 23-28, 2018: Prime Minister Abe and Foreign Minister Kono visit New York for UN General Assembly meeting.

Sept. 23, 2018: Prime Minister Abe and President Trump meet for dinner at Trump Tower in NYC.

Sept. 26, 2018: President Trump and Prime Minister Abe meet on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly. They announce the two countries will enter into negotiations for a Japan-United States Trade Agreement on goods and services. Joint Statement.

Sept. 30, 2018: Denny Tamaki is elected governor of Okinawa.

Oct. 6, 2018: Secretary of State Pompeo and Foreign Minister Kono meet in Tokyo.

Oct. 8, 2018: Secretary of State Pompeo and Foreign Minister Kono speak by telephone about Pompeo’s visit to North Korea on Oct. 7.

Oct. 9, 2018: Parliamentary Vice Minister for Foreign Affairs Tsuji Kiyoto meets family members of former Prisoners of War (POWs) in Tokyo.

Oct. 17, 2018: Central Japanese government asks land ministry to review and invalidate Okinawa Prefectural government decision that suspended relocation work on US Marine Corps Air Station Futenma.

Oct. 24, 2018: US and Japan hold the second meeting of the Japan-United States Strategic Energy Partnership in Tokyo.

Oct. 25-27, 2018: Prime Minister Abe visits China where he meets President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang.

Oct. 29, 2018: Prime Minister Abe and Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi hold Japan-India summit meeting in Tokyo.

Oct. 29-31, 2018: Senior officials from Japan and the US hold bilateral Extended Deterrence Dialogue in Tokyo.

Nov. 1, 2018: Japanese central government resumes work on relocation of Marine Corps Air Station Futenma after reversing the ban by Okinawa’s Prefectural government.

Nov. 4, 2018: Foreign Minister Kono discusses US-Japan trade talks and disputes with South Korea in an interview with Bloomberg.

Nov. 6, 2018: Mid-term elections take place for US congressional, state, and local offices.

Nov. 12-13, 2018: Vice President Mike Pence visits Japan and meets Prime Minister Abe and Deputy Prime Minister Aso Taro. Joint Statement.

Nov. 13, 2018: Governor of Okinawa Tamaki pledges to hold a referendum on the relocation of US Marine Corps Air Station Futenma sometime in early 2019.

Nov. 13, 2018: Deputy Secretary of State John Sullivan meets Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs Akiba Takeo in Tokyo.

Nov. 15, 2018: Senior officials from the US, Japan, Australia, and India meet in Singapore for consultations on the Indo-Pacific region.

Nov. 27, 2018: Okinawa Gov. Tamaki announces he will hold the relocation referendum for US Marine Corps Air Station Futenma on Feb. 24, 2019.

Nov. 30, 2018: Prime Minister Abe and President Trump meet on sidelines of G20 Summit in Argentina.

Nov. 30, 2018: President Trump, Prime Minister Abe, and Prime Minister Modi meet on sidelines of the G20 summit in Argentina.

Dec. 1, 2018: Prime Minister Abe and Russian President Vladimir Putin agree on a framework for talks on a bilateral peace treaty.

Dec. 8, 2018: President Trump announces that White House Chief of Staff John Kelly will resign by the end of the year.

Dec. 10, 2018: US Trade Representative (USTR) holds a public hearing regarding a proposed US-Japan Trade Agreement.

Dec. 18, 2018: Abe Cabinet announces the 2018 National Defense Program Guidelines (NDPG) and the 2019-2023 Mid-Term Defense Program.

Dec. 20, 2018: South Korean Navy destroyer locks fire-control radar onto a Maritime Self-Defense Force P-1 patrol aircraft in the Sea of Japan, according to Japanese Ministry of Defense.

Dec. 20, 2018: Secretary of Defense James Mattis announces resignation and plan to leave office by the end of February.

Dec. 21, 2018: USTR releases its negotiating objectives for possible US-Japan trade agreement.

Dec. 23, 2018: President Trump announces that he will remove Secretary of Defense Mattis early from his office on Jan. 1. Deputy Secretary of Defense Patrick Shanahan will take over as acting secretary of defense.

Dec. 28, 2018: Japanese Ministry of Defense releases video footage of the incident with the South Korean destroyer on Dec. 20.

Dec. 30, 2018: The 11-nation Comprehensive Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP, or TPP-11) enters into force.