Articles

In the wake of the death of former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo, the fall brought unexpectedly turbulent politics for Prime Minister Kishida Fumio. In the United States, however, President Joe Biden welcomed the relatively positive outcome of the midterm elections, with Democrats retaining control over the Senate and losing less than the expected number of seats in the House. Diplomacy continued to be centered on various impacts of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, but both Biden and Kishida focused their attention on a series of Asian diplomatic gatherings to improve ties. Chinese President Xi Jinping’s attendance at the G20 Meeting in Bali and APEC gathering in Bangkok proffered the opportunity finally for in-person bilateral meetings for both leaders. Finally, Japan’s long awaited strategic documents were unveiled in December. A new National Security Strategy (NSS) took a far more sober look at China’s growing influence and included ongoing concerns over North Korea as well as a growing awareness of Japan’s increasingly difficult relationship with Russia.

Accompanying the NSS is a 10-year defense plan, with a five-year build-up commitment, that gave evidence that Kishida and his ruling coalition were serious about their aim to spend 2% of Japan’s GDP on its security. The desire for greater lethality was also there, with the inclusion of conventional strike investment.

Politics in Play for Kishida and Biden

On Sept. 27, the Kishida administration hosted a state funeral for Abe at the Nippon Budokan Hall in Tokyo. More than 4,300 guests attended the ceremony to pay their respects to the former prime minister, including the leaders of Australia, Cambodia, India, Singapore, and Vietnam. Vice President Kamala Harris led the US delegation, which also featured US Trade Representative Katherine Tai, Ambassador to Japan Rahm Emanuel, National Security Advisor to the Vice President Philip Gordon, former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Adm. Michael Mullen, Commandant of the US Coast Guard Adm. Linda Fagan, former Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage, former National Security Advisor Stephen Hadley, and the last four US ambassadors to Japan (Bill Hagerty, Caroline Kennedy, John Roos, and Thomas Schieffer).

Kishida’s decision to hold a state funeral for Abe was an unusual one. While state funerals for political leaders used to be more common prior to World War II, after the war, the state funeral law was abolished. Instead, the tradition became for funerals for prime ministers to be organized jointly between the state and the leader’s political party. The only other state funeral for a prime minister was held in 1967 for Yoshida Shigeru, who signed the San Francisco Treaty ending the US occupation of Japan and restoring Japan’s relations with the Allied powers. However, Kishida said that the state funeral for Abe was “appropriate” given his tenure as Japan’s longest-serving prime minister and his security and economic policy achievements that elevated the country’s status on the international stage.

Figure 1 Abe Akie, the widow of former Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzo, carries his ashes past Japan’s Prime Minister Kishida Fumio as she arrives for the start of his state funeral. Photo: Philip Fong/AFP

Nevertheless, Abe’s state funeral prompted considerable opposition within Japan. Nearly all major public opinion polls found that over half of the public opposed the state funeral. Among opponents, many expressed a sense that their government was forcing them to mourn Abe despite his divisive legacy. Others criticized the lack of a clear legal basis and high estimated cost to taxpayers of 1.7 billion yen ($12 million), a figure the government later said was closer to 1.2 billion yen ($8 million). The state funeral also rankled many who felt that Kishida had not done enough to address Abe and other LDP members’ ties to the Unification Church, a link believed to be a major motivation behind Yamagami Tetsuya’s decision to assassinate Abe.

On this last point, Kishida made repeated efforts throughout the fall to demonstrate his government’s and his party’s commitment to distancing themselves from the Unification Church—and to holding the church accountable for its predatory practices. On Aug. 31, Kishida said that the LDP would cut all ties with the church. He also announced that he had tasked LDP Secretary General Motegi Toshimitsu with conducting a party-wide survey of all Diet members’ connections to the group. A week later, Motegi shared his findings that around half of LDP lawmakers had dealings with the church.

On Oct. 17, Kishida announced a formal investigation of the Unification Church. Depending on the outcome of the investigation, and after a subsequent court judgment, the church could lose its official status as a religious corporation and its related tax benefits, though it would still be allowed to conduct activities in Japan. Kishida’s government also became the first ever to invoke the “right to question” provision of the Religious Corporation Law to seek information from the Unification Church about its operations. On Dec. 10, Japan’s Parliament further enacted a law banning organizations from maliciously soliciting donations, which was intended to address the controversy surrounding the fundraising practices of the church.

Despite Kishida’s efforts, the Japanese public still appears unsatisfied. The approval rating for the prime minister continued to decline month after month, with some polls indicating that by December, Kishida’s support rating had fallen below 30% and entered the so-called “danger zone” where prime ministers risk losing office. The final months of 2022 also witnessed four of Kishida’s Cabinet ministers resign from their posts for reasons including Unification Church ties, death penalty comments, and funding scandals.

In the United States, Biden’s approval ratings were also low but managed to hold steady throughout the fall at about 40 to 45%. Some polls even suggest that Biden may have received a minor bump in approval after his Democratic Party performed better than expected in the midterm elections on Nov. 8. In most midterm elections, losses for the incumbent party are the norm. The Democratic Party did lose control of the House of Representatives to the Republican Party, as expected, but surprisingly maintained their control of the Senate.

The midterm results mean that the United States will enter a new period of divided government when Congress begins its next session in January. While Republican leaders in the House are already facing challenges in governing with their slim majority, many expect the party to at least find common cause in stymieing much of Biden’s legislative agenda for the next two years. The silver lining for the Democratic Party is that their Senate majority should allow the Biden administration to continue making senior appointments in the executive and judicial branches without significant opposition.

Two points are worth keeping an eye on in the months ahead. First, US support for Ukraine is expected to be a focal point for the new Congress. Second, there now seems to be uniform skepticism on both sides of the aisle about China. Last July, Kevin McCarthy praised Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi’s Taiwan visit and said that he, too, would visit Taiwan if he became speaker. After a historic 15 rounds of voting, McCarthy was finally elected speaker on Jan. 7, though as of this writing we have yet to hear if he will follow through with his Taiwan pledge.

Ramping up Japan’s Defense

2022 proved a watershed year for Japan’s military planning. A new National Security Strategy, crafted across the Cabinet, laid out a stark assessment of Japan’s view of the world. China loomed large, of course, with the strategy saying that Japan would “strongly oppose China’s growing attempts to unilaterally change the status quo by force, demand it to not conduct such activities, and respond in a calm and resolute manner.”

Threats were identified as the main driver of a wholesale change in Japan’s defense planning. China, North Korea, and Russia were singled out for particular attention, but it is clearly China that dominates Japanese thinking. Beijing’s intentions toward Taiwan were clearly on the minds of planners, and there were signs, too, that the Russian invasion of Ukraine had created a deeper sense of urgency in Japanese military planning. The 10-year defense plan includes an across-the-board improvement in capabilities and suggests that the SDF needs to ready itself for the possibility of a major conflict. From new weapons systems, such as long-range missiles, to an emphasis on the new domains of space and cyber, to the nuts and bolts of military readiness—such as ammunition, fuel, and other supplies required for sustained warfighting—the plan covered all bases in the SDF’s needs should a crisis erupt.

New organizational changes were also suggested. The SDF will now have a joint operational command, a reform that has been discussed since the response to the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake demonstrated the need for integrated command. An important expansion of cyber security personnel is also planned, adding another capability for offensive operations if required to defend Japan. Planned upgrades in intelligence gathering include integrating signals intelligence with human intelligence capabilities. Furthermore, the Japanese Ministry of Defense also pointed to the need to ready both military and civilian airfields and ports for use in the case of a conflict. The list of upgrades is comprehensive.

Washington was quick to commend Japan’s doubling down on its defenses. Both Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin publicly acknowledged the importance of this comprehensive commitment to improving Japan’s military. In press statements, Blinken said that “Japan’s new documents reshape the ability of our Alliance to promote peace and protect the rules-based order,” while Austin praised Japan’s actions as underpinning “continuing bilateral efforts to modernize the Alliance, bolster integrated deterrence, and address evolving regional and global security challenges through cooperation with likeminded allies and partners.”

Tokyo’s strategic review paved the way for a similar adjustment in US-Japan alliance force posture and an eventual revision of the expected roles and missions between the two militaries once Japan’s capabilities are enhanced. The three strategy documents also reveal the extent to which Japan is readying itself for security cooperation with two other US allies: Australia and the UK. On Oct. 22, Japan and Australia signed a new defense agreement, and on Jan. 11, Japan and the UK concluded their Reciprocal Access Agreement to allow their forces to operate in each other’s countries. Japan and the US are also deepening their cooperation on providing security assistance to the Philippines.

Yet, for all this ambition, there remain considerable knots to untie in terms of implementation. First, and perhaps most important, Prime Minister Kishida will need to finance his ambitious new military plan. Over the next five years, a projected budget of 43 trillion yen ($318 billion) will be needed. Already, in early December, political lines were being drawn prior to announcing the new strategic documents. The Ministry of Finance, of course, wants to avoid increasing the national debt, and Kishida said he, too, is concerned about funding his defense expansion through bonds. Instead, Kishida would like to ask the Japanese to pay an added defense tax. Whether this would be a tax aimed primarily at corporate Japan or at individual citizens remains unclear. But few Japanese welcomed the idea of new taxes, especially as Japan sought to emerge from the economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic.

A second challenge is for the alliance. The prospect of increasing tensions between China and Taiwan makes it imperative that Tokyo and Washington align their planning for a possible crisis or, in a worst-case scenario, a conflict across the Taiwan Strait. Japan’s defenses writ large will be at stake should the United States and China find themselves at war, but it remains unclear if and how the SDF can play a role directly in a Taiwan scenario. Another knot that will take time to untangle for the US-Japan alliance is how Japan’s decision to introduce conventional strike capability will be addressed in allied military planning. While the added capability is a welcome addition to the combined US-Japan deterrent, political questions about how and when that capability will be used remain to be explored.

US-Japan Diplomatic Alignment

Beyond the security upgrades of late, there has been a remarkable calibration of US-Japan diplomacy. Two examples illustrate this in the fall of 2022. First, in a series of multilateral gatherings in Asia, President Biden and Prime Minister Kishida had the opportunity to engage directly with Chinese President Xi Jinping, the first in-person meetings since the dramatic rise in tensions after Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to the region. The G20 meeting hosted by Indonesia in Bali on Nov. 15-16 began a week-long Asian diplomatic engagement. Biden and Xi had a three-hour long conversation on the sidelines that prompted the two to commit to high-level discussions on how to mitigate the risk of escalated tensions between the two militaries.

Biden reiterated that US-China competition should not veer into conflict and underscored the need for the United States and China to manage their competition responsibly and maintain open lines of communication. The two leaders discussed the importance of developing principles that would advance these goals and tasked their teams to discuss them further.

Talks covered a range of topics, including in a series of follow-up meetings. In December, Assistant Secretary of State for East Asia and Pacific Affairs Daniel Kritenbrink and National Security Council Senior Director for China and Taiwan Laura Rosenberger traveled to Beijing to prepare for a visit there in early 2023 by Secretary of State Blinken. Perhaps, too, there will be a visit to Washington, DC by President Xi in 2023.

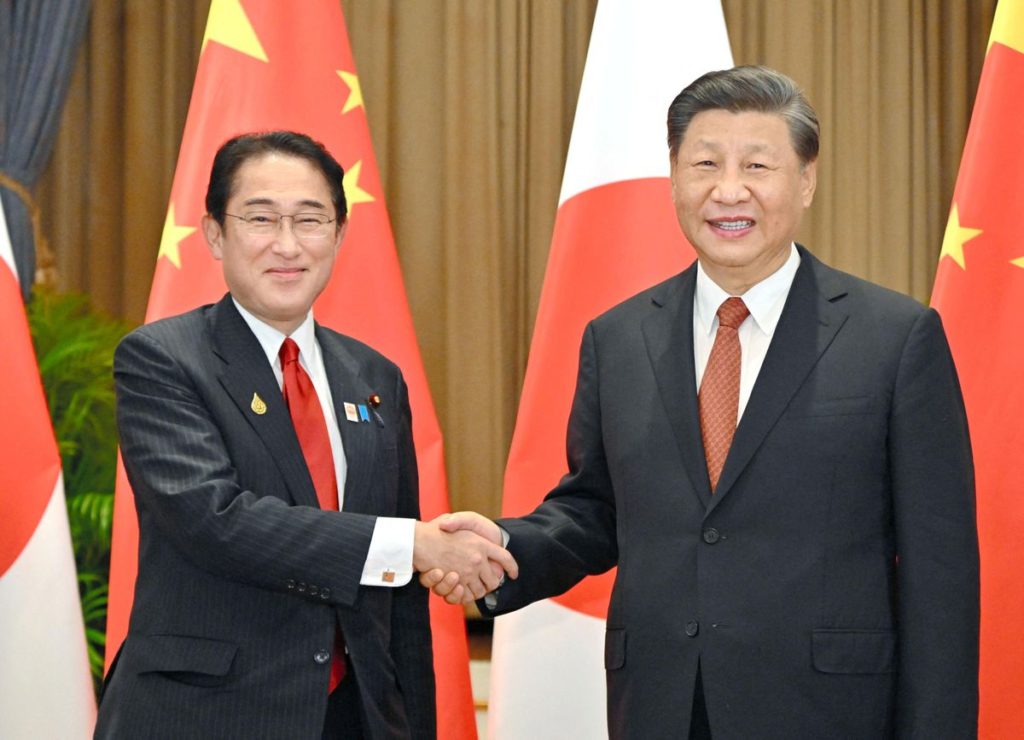

On Nov. 17, Kishida had his bilateral meeting with Xi on the sidelines of the APEC meeting in Bangkok. After August’s military tensions over Taiwan, then Foreign Minister Wang Yi canceled a scheduled meeting with Japanese Foreign Minister Hayashi Yoshimasa. But weeks later, Kishida’s National Security Advisor Akiba Takeo traveled to China where he met State Councilor Yang Jiechi. Foreign Minister Hayashi had hoped to visit Beijing by year’s end as a follow up to the prime minister’s meeting with Xi, but China postponed the visit after Japan announced its new National Security Strategy. In the meantime, a new Chinese foreign policy team has been announced. The newly appointed foreign minister is Qin Gang, formerly ambassador to the United States and confidante to Xi, and former Foreign Minister Wang Yi has been promoted to the Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party, where he is expected to wield considerable influence over China’s foreign policy.

Figure 2 Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio meets Chinese President Xi Jinping on the sidelines of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit in Bangkok. Photo: Kyodo via Reuters

Yet, the remarkable convergence of diplomacy between the United States and Japan is not all about China. Washington and Tokyo are firmly aligned also in the broader global effort to respond to Russian aggression against Ukraine. Indeed, the visit of Kishida to Washington on Jan. 13 was the final stop in a G7 tour designed to craft an agenda for the next G7 meeting in May, which will be hosted by Japan. Taking place in the prime minister’s home district of Hiroshima, the G7 will not only continue to align their cooperation with Ukraine but will also address the rising nuclear risk posed by threats to use these weapons of mass destruction from Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Kishida visited France, Italy, and the UK before heading to Canada and then to the United States. All along the way, the situation in Ukraine was a focal point of discussion as the Japanese prime minister began to build his agenda for the upcoming G7 Summit. But Japan’s own desire for deeper security cooperation with the NATO allies was also evident. In Italy, Kishida and Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni announced their new strategic partnership. Already, Italy joined the Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP) alongside UK and Japanese defense manufacturers to build a new next-generation fighter. In France, President Emanuel Macron committed to further security cooperation with Japan in the Indo-Pacific, especially on missile and nuclear proliferation by North Korea, as well as on the global economic difficulties created by the Russian invasion. In the UK, Kishida signed a Reciprocal Access Agreement to allow the Japanese and UK forces to exercise and train on each other’s soil. Before heading to Washington, Kishida’s final stop was in Ottawa to meet with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. On the agenda there was not only the Ukraine situation but also the Indo-Pacific, following Canada’s announcement of its own new Indo-Pacific strategy.

Arriving in Washington, DC, Kishida had much to discuss with Biden. Biden praised Kishida’s watershed defense reforms but also spent their time together discussing how best the United States and Japan could continue their diplomatic efforts to counter Russian aggression and the world’s growing concern about Chinese ambitions. At a range of meetings earlier in the week, including a 2+2 meeting on Jan. 11, a meeting at NASA between Foreign Minister Hayashi and Secretary of State Blinken to highlight a new era of space cooperation, and a meeting at the Pentagon between Defense Minister Hamada Yasukazu and Secretary of State Austin, the US and Japan rolled out a broad range of new initiatives designed to accentuate the capabilities that will be brought to bear for the alliance during this era of intense strategic alignment.

Figure 3 US President Joe Biden and Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio at the White House on Jan. 13, 2023. Photo: T.J. Kirkpatrick/Pool via Reuters

Conclusion

Diplomacy will continue to be front and center for the United States and Japan in 2023. Kishida will host the G7 Summit in Hiroshima in May and will highlight Japan’s continuing commitment to reducing the risk of nuclear weapons. Russia’s war in Ukraine shows few signs of ending. Another North Korean nuclear test is expected. This year, Japan joins the UN Security Council for a two-year assignment as a nonpermanent member. Expect nuclear risk to also be high on the Japanese government’s agenda during this era of Security Council strain.

In the Indo-Pacific, 2023 should be a good year for the US-Japan-South Korea trilateral as diplomacy has yielded cautious optimism that the governments in Japan and South Korea continue to work through difficult bilateral issues. Prime Minister Kishida has stated his hope to invite President Yoon Suk Yeol to join the G7 nations in May. The Quad will continue to develop its agenda for Indo-Pacific cooperation and Australia is due to host the next leaders’ summit in mid-2023. Finally, later in the year, the United States will host the APEC meeting in San Francisco and provide opportunity for enhanced economic cooperation.

Politics at home will continue to draw the focus of both Kishida and Biden. In Japan, local elections in April are expected to be difficult for both the LDP and Komeito, and there is much chatter in Tokyo around what this might mean for the prime minister’s future. The government’s finances and especially concern over how to manage its debt has created tensions within the LDP as well as debate more broadly over how to pay for the Kishida Cabinet’s new priorities on defense and family support subsidies. A new Bank of Japan governor will be appointed in 2023 as Kuroda Haruhiko steps down.

In the United States, a fractured Republican party has taken control over the House. The difficulties within the party, demonstrated by the inability for days to unify around a new speaker, suggest a tumultuous time ahead for Congress. And already, who might run for the 2024 presidential election invites considerable speculation.

Sept. 5-6, 2022: Director General of the Foreign Policy Bureau Keiichi Ichikawa, Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asian Affairs Donald Lu, and Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs Camille Dawson attend Quad Consultations in Delhi, India.

Sept. 6, 2022: Minister for Foreign Affairs Hayashi speaks by telephone with Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo.

Sept. 8-9, 2022: US Trade Representative Katherine Tai, Secretary of Commerce Raimondo, METI Minister Yasutoshi Nishimura, and State Minister for Foreign Affairs Kenji Yamada attend the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF) Ministerial in Los Angeles.

Sept. 8, 2022: LDP Secretary General Toshimitsu Motegi announces that about half of LDP members have ties to the Unification Church.

Sept. 21, 2022: President Biden meets Prime Minister Kishida on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly Meeting in New York.

Sept. 21, 2022: Prime Minister Kishida attends High-Level Meeting of the Friends of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty on sidelines of the UN General Assembly (UNGA).

Sept. 21, 2022: Prime Minister Kishida meets with Bill Gates, co-chair of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly Meeting in New York.

Sept. 22, 2022: Secretary of State Blinken, Minister for Foreign Affairs Hayashi, and South Korean Minister of Foreign Affairs Park Jin meet on the sidelines of the UNGA.

Sept. 22, 2022: Prime Minister Kishida visits New York Stock Exchange to deliver remarks and ring the closing bell.

Sept. 23, 2022: Secretary of State Blinken, Minister for Foreign Affairs Hayashi, Australian Foreign Minister Penny Wong, and Indian External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar attend the Quad Foreign Ministers’ Meeting on the sidelines of the UNGA.

Sept. 23, 2022: Secretary of State Blinken and Minister for Foreign Affairs Hayashi attend the COVID-19 Global Action Plan Foreign Ministerial Meeting on the sidelines of the UNGA.

Sept. 23, 2022: President Biden announces a presidential delegation to Japan to attend the State Funeral of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

Sept. 26, 2022: Vice President Harris meets Prime Minister Kishida during her trip to Tokyo to attend the State Funeral of former Prime Minister Abe.

Sept. 27, 2022: US Special Representative for the DPRK Sung Kim, Director General for Asian and Oceanian Affairs Bureau Takehiro Funakoshi, and South Korean Special Representative for Korean Peninsula Peace and Security Affairs Kim Gunn speak by telephone

Sept. 27, 2022: State funeral for former Prime Minister Abe is held in Tokyo.

Oct. 4, 2022: North Korea launches an intermediate-range ballistic missile that flies over Japan.

Oct. 4, 2022: Secretary of State Blinken, Minister for Foreign Affairs Hayashi, and South Korean Foreign Minister Park Jin speak by telephone.

Oct. 4, 2022: Prime Minister Kishida speaks by telephone with President Biden.

Oct. 4, 2022: Foreign Minister Hayashi speaks by telephone with Secretary of State Blinken.

Oct. 4, 2022: Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman, Vice Minister for Foreign Affairs Takeo Mori, and South Korean First Vice Foreign Minister Cho Hyun-dong speak by telephone.

Oct. 7, 2022: US Special Representative for the DPRK Sung Kim, Director General for Asian and Oceanian Affairs Bureau Takehiro Funakoshi, and South Korean Special Representative for Korean Peninsula Peace and Security Affairs Kim Gunn speak by telephone.

Oct. 11, 2022: Japan reopens to foreign tourists without visas.

Oct. 17, 2022: Prime Minister Kishida announces formal investigation of the Unification Church.

Oct. 20, 2022: Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and UN Under-Secretary General Izumi Nakamitsu discuss gender equality at an event in Tokyo.

Oct. 24, 2022: Economic Revitalization Minister Daishiro Yamagiwa resigns from Kishida’s Cabinet.

Oct. 25, 2022: Deputy Secretary of State Sherman meets with Vice Minister for Foreign Affairs Mori Takeo in Tokyo.

Oct. 25, 2022: Deputy Secretary of State Sherman, Vice Minister for Foreign Affairs Mori, and South Korean First Vice Foreign Minister Cho hold a trilateral meeting.

Oct. 26, 2022: Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security Bonnie Jenkins, State Minister of Economy, Trade, and Industry Ota Fusae, Assistant Secretary for Nuclear Energy Kathryn Huff, and Ghana’s Deputy Minister of Energy William Owuraku Aidoo announce a collaboration to support deploying small modular reactor technology in Ghana.

Oct. 27, 2022: Department of Defense releases its Nuclear Posture Review.

Oct. 27, 2022: Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security Jenkins and State Minister of Economy, Trade, and Industry Ota announce the Winning an Edge Through Cooperation in Advanced Nuclear (WECAN) Partnership.

Nov. 4, 2022: Secretary of State Blinken and Minister for Foreign Affairs Hayashi meet on the sidelines of the G7 Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in Munster Germany.

Nov. 8, 2022: US holds midterm elections for the Congress and many local offices.

Nov. 11, 2022: Justice Minister Yasuhiro Hanashi resigns from Kishida’s Cabinet.

Nov. 13, 2022: President Biden and Prime Minister Kishida meet on the sidelines of the ASEAN-related Summit Meetings in Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

Nov. 13, 2022: Prime Minister Kishida, President Biden, and South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol meet on the sidelines of the ASEAN-related Summit Meetings in Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

Nov. 15, 2022: President Biden, Prime Minister Kishida, and Indonesian President Widodo announce the launch of the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) in Indonesia.

Nov. 15-16, 2022: Japan-US Extended Deterrence Dialogue is held at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Tokyo.

Nov. 18, 2022: North Korea launches an intercontinental ballistic missile.

Nov. 20, 2022: G7 Foreign Ministers release a joint statement condemning North Korea’s launch of an intercontinental ballistic missile.

Nov. 20, 2022: Minister for Internal Affairs and Communications Terada Minoru resigns from Kishida’s Cabinet.

Nov. 21, 2022: Deputy Secretary of State Sherman, Vice Foreign Minister Mori, and Korean First Vice Foreign Minister Cho speak by telephone about North Korea’s missile launch.

Dec. 1, 2022: Assistant Secretary of State for Energy Resources Geoffrey Pyatt and METI Director General Ryo Minami hold the inaugural US-Japan Energy Security Dialogue in Tokyo.

Dec. 10, 2022: Japan’s Diet enacts law to ban organizations from maliciously soliciting donations.

Dec. 13, 2022: US Special Representative for the DPRK Sung Kim, Director General for Asian and Oceanian Affairs Takehiro Funakoshi, and South Korean Special Representative for Korean Peninsula Peace and Security Affairs Kim Gunn meet in Jakarta.

Dec. 13, 2022: Governor of Maryland Lawrence Hogan, Jr. and Ambassador of Japan to the US Tomita Koji sign and renew the Memorandum of Cooperation on Economic and Trade Relations between Japan and Maryland.

Dec. 15, 2022: Director-General of the North American Affairs Bureau Kobe Yasuhiro meets with Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs Daniel Kritenbrink in Tokyo.

Dec. 16, 2022: Japan releases new National Security Strategy, National Defense Strategy, and Defense Buildup Program.

Dec. 16, 2022: Japan’s Cabinet approves plan to double the amount earmarked for Japan’s defense.

Dec. 20, 2022: Minister for Foreign Affairs Hayashi, METI Minister Nishimura, and Secretary of Commerce Raimondo attend the online IPEF Ministerial.

Dec. 27, 2022: Reconstruction Minister Akiba Kenya resigns from Kishida’s Cabinet.