Articles

2020 brought a global pandemic, economic strain, and, in both the United States and Japan, leadership transitions. COVID-19 came in waves, smaller to be sure in Japan than in the United States, and each wave intensified public scrutiny of government. Neither Tokyo nor Washington held up well. Public opinion continued to swing against President Donald Trump, increasing his disapproval rating from 50% in January to 57% in December following the US presidential election. Prime Minister Abe Shinzo also suffered a loss of confidence. His disapproval rating grew from 40% in January to 50% in July, cementing his decision to step down on Aug. 28, ostensibly for health reasons.

Yet, the transition process could not have been more different. In Japan, the LDP organized an election for party leadership, one that limited participation among local members and focused attention on those in the national legislature. Factional leaders took an early role in building a consensus for a managed succession, and on Sept. 16, Abe’s chief Cabinet secretary for almost eight years, Suga Yoshihide, stepped in. A continuity Cabinet was formed.

In the United States, however, a far more volatile and contentious campaign for the presidency led to an unprecedented transition process. The stakes were high. Two-thirds of eligible Americans voted in the 2020 election, the highest since 1900. Democratic candidate Joe Biden and his running mate, Kamala Harris, garnered 306 of the 538 Electoral College votes, winning the contest. But President Trump refused to concede, claiming his victory had been “stolen” and launching repeated legal challenges in many of the swing states. No evidence was brought to bear on the challenges, and on Dec. 14, the formal count of the Electoral College confirmed the Biden-Harris victory. Few, then, would have predicted the shocking events that followed on Jan. 6 when Congress was overtaken by a violent mob as it was certifying these results.

Bilaterally, while all eyes were on the leadership changes in Tokyo and Washington, allied military cooperation continued. The two governments continued their quiet discussion on Host Nation Support, Japanese government financial support for the deployment of US Forces in Japan. Chinese forces in the region reminded both militaries that the stakes in the Indo-Pacific remain high. A new commander was nominated for the US Indo-Pacific command. And Japan’s new defense minister, Kishi Nobuo, Abe’s younger brother, signaled Japan’s determination to strengthen its offshore capabilities as analysts waited to see how the Ministry of Defense would resolve its ballistic missile defense conundrum.

Abe Resigns, Suga Steps Up

By summer’s end, the longest-serving prime minister of Japan, Abe, faced considerable headwinds. His approval rating had dropped considerably, from 49% at the beginning of 2020 to 36% by Aug. 23. COVID-19 had shaken public confidence in Abe’s leadership, a fate that many leaders in democratic nations also shared. But Abe had additional political scandals to account for and once more his health seemed to be failing. Several visits to the hospital revealed the year’s strain on Abe’s physical strength, and on Aug. 28, he announced his intention to step down from leadership of his party and country.

On Sept. 1, the secretary-general of the Liberal Democratic Party, Nikai Toshihiro, announced the party’s leadership election would be a limited one due to Abe’s inability to fulfill his term. This limited the role of the more than 1 million grassroots party members to just 141 prefectural delegates, thereby giving the 394 lawmakers elected to the Diet the predominant voice in determining who would succeed Abe. Factional heads met in rounds of discussions over who to back, and in the end, three candidates stood for consideration: Kishida Fumio, Abe’s former foreign minister; Suga, Abe’s chief Cabinet secretary; and Ishiba Shigeru, a critic of Abe with strong backing among rank-and-file party members. None of the next-generation leaders in the party threw their hat in the ring, choosing instead to wait for the anticipated next round after the 2021 Lower House election. Suga was the clear winner, with many seeing him as the logical caretaker to the Abe Cabinet’s agenda. His role as the prime minister’s right-hand man throughout Abe’s long tenure in office meant that Suga had helped formulate that agenda, and as chief Cabinet secretary had an indispensable role in its implementation. Continuity in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic won the day.

Figure 1 Yoshihide Suga pictured in the Parliaments’s lower house after being elected as Prime Minister. Photo: Koji Sasahara/AP

Suga took over as prime minister on Sept. 16 with the surprisingly high approval rating of 74%, the third highest for any Cabinet after those of former prime ministers Koizumi Junichiro and Hatoyama Yukio. Suga’s early speeches highlighted his focus on better and more responsive governance, and he argued strongly for Japan to accelerate its transition to a digital economy. He announced plans to create a new agency directly responsible for this and appointed one of the leading future contenders for party leadership, Kono Taro, to head up his effort to eliminate the stovepipes and regulatory complications that hindered the government’s responsiveness to the needs of Japanese citizens. COVID-19 has revealed the costs of Japan’s slow adaptation to new platforms and communications technology.

But Suga’s honeymoon with the public was short-lived. By October, his approval rating began to drop. An early tussle with academic appointments to the Science Council of Japan’s General Assembly was widely perceived as a vendetta against those who had criticized the Abe Cabinet. The real challenge for the new Suga Cabinet, however, proved to be problems he inherited from the Abe era. Abe was under investigation by Japanese prosecutors for using political funds to pay for dinners at luxury hotels for supporters ahead of the annual cherry blossom viewing parties and for giving false testimony in the Diet about the spending. Furthermore, the Suga Cabinet also drew public criticism for its pandemic policies. The Go To Travel campaign designed to boost domestic tourism was widely criticized, as was the government’s determination to move ahead with the Tokyo Olympics as cases of COVID-19 infection began picking up again. In late December, Japan crossed the 200,000 mark in terms of total COVID-19 cases, as well as the 3,000 mark for coronavirus-related deaths. On Jan. 7, the Suga Cabinet declared a state of emergency in the Tokyo metropolitan area.

Suga seems to be on firmer ground diplomatically, however, leaving little room for doubt that Japan’s strategic focus on the shifting balance of power in the region continues uninterrupted. As Japan waits for the new Biden administration to take office and its Asia policy to take shape, the Suga Cabinet has not stepped back from its regional activism. The Indo-Pacific vision that frames Japan’s relations with others across the region remains paramount, and the new prime minister and his Cabinet wasted no time in demonstrating Japan’s continued leadership in building Indo-Pacific cooperation. Within weeks of assuming office, the prime minister traveled to Vietnam and Indonesia where he reiterated Japan’s Indo-Pacific vision. Not long after, Suga gave a speech at the Japan-ASEAN Summit emphasizing the need for regional consensus to “cooperatively work towards the further prosperity of a free and open Indo-Pacific.” Suga’s new defense minister, Kishi Nobuo, also continued to move forward expeditiously with Japanese security cooperation with others around the region. On Sept. 9, Japan’s ambassador to India signed a new defense agreement with India’s minister of defense, establishing an Access and Cross-Servicing Agreement (ACSA), followed by a similar agreement on Nov. 17 between the defense ministers of Japan and Australia to enable bilateral visits for training and operations on Nov. 17.

Figure 2 Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga and Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc wave during a welcome ceremony at the Presidential Palace in Hanoi during Suga’s official visit to Vietnam in October 2020. Photo: AP Photo/Minh Hoang, Pool

Suga has also deftly handled the difficult politics of the US presidential transition. Despite Trump’s challenge of the election outcome, Suga spoke with Biden over the phone about the alliance on Nov. 12, five days after Biden was declared president-elect. After the call, Suga noted how pleased he was about Biden’s unprompted assurances that the United States would continue to offer Article 5 protections for the Senkaku Islands, islands claimed also by China. Even before that call there were signs that Tokyo and Washington would return to emphasizing their shared priority on addressing global challenges. Suga had announced on Oct. 26 that Japan intended to be carbon neutral by 2050, undoubtedly welcome news for the Biden transition team, which emphasizes addressing the threat of climate change as a national security priority. And on Dec. 25, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced that longtime Washington hand, Tomita Koji, would be the next Japanese ambassador to the United States.

A Biden-Harris Win and a Rocky US Transition

On Nov. 3, the United States held general elections for the presidency, a third of the seats in the Senate, all seats in the House of Representatives, and a variety of state and local offices. While many polls in the leadup to the election projected that the Democrats would expand their majority in the House and recapture a majority in the Senate, the actual results were much closer than predicted, with Republican candidates exceeding expectations in many contests. In the House, the Democrats retained control, but their majority shrank from 232 to 222 of 435 seats, with two seats still contested as of this writing. In the Senate, the Democrats gained at least one seat but fell short of a majority with 48 of 100 seats. However, the two Senate races in Georgia were close enough to trigger runoff elections on Jan. 5. The runoff races were tightly contested, but in the end the Democrats captured both seats. The partisan balance of the new Senate will thus be tied at 50-50 when it convenes later in January, but Democrats will have effective control because it will be up to Vice President Kamala Harris to cast the deciding vote.

As close as elections were in the House and Senate, it was the presidential election that garnered the most attention. By the end of election night on Nov. 3, results seemed to favor the Democratic ticket of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris over Republican incumbents Donald Trump and Mike Pence, but the race was too close to call in several states such as Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania. The COVID-19 pandemic played a large role in delaying the official vote tally, both because of additional safety precautions at ballot counting centers and because a historic number of citizens cast their ballots via mail rather than in person. Many Americans and international observers watched closely as vote results trickled in over the next few days. Finally, on Nov. 7, the Associated Press and other major networks called Pennsylvania for Biden and Harris, putting them above the minimum 270 Electoral College votes needed to win the election.

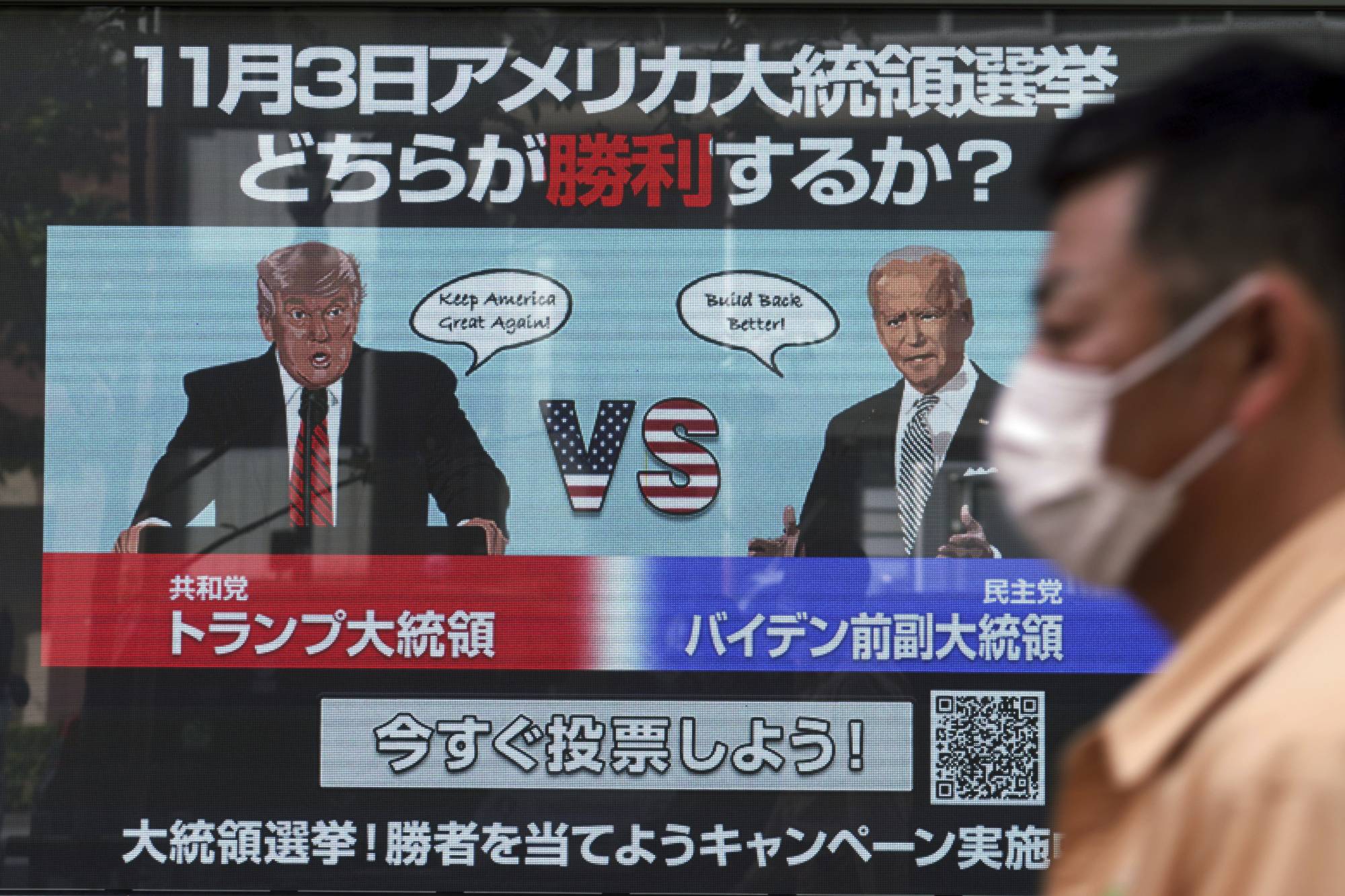

Figure 3 A digital screen in Tokyo depicts Republican candidate Donald Trump and Democratic candidate Joe Biden. Photo: AP

As Suga and other international leaders moved to congratulate Biden and Harris on their victory, Trump refused to concede and spent the remainder of 2020 trying to overturn the results by spreading baseless claims of election fraud. The Trump campaign and their allies went to court in six states with allegations of fraud but lost more than 50 lawsuits as their efforts were struck down by judges from across the political spectrum. Perhaps the most prominent case came when the state government of Texas filed a lawsuit directly in the Supreme Court challenging election procedures in Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. This unprecedented attempt by a state to overturn the election results in four other states received significant support from Republicans, including Trump, attorneys general in 17 states, and nearly two-thirds of House Republicans. However, on Dec. 11, the Supreme Court rejected the lawsuit, saying that Texas lacked standing to bring the case before the court.

Three days later, the Electoral College convened on Dec. 14 and officially confirmed Biden’s victory. In the end, Biden received 306 Electoral College votes compared to 232 for Trump, a margin that was nearly identical to Trump’s victory over Hilary Clinton in 2016, when he won 304 Electoral College votes. Biden received more than 81 million votes, the most ever cast for a presidential candidate, with Trump receiving the second most at over 74 million votes. All told, the 2020 election saw the highest voter turnout (66.5%) in over a century.

Despite their many setbacks in court, state legislatures, and the Electoral College, President Trump and his team steadfastly refused to accept the results. Officials within the Trump administration who dared to openly contradict the president by saying that there was no evidence of election fraud were fired or resigned. By the end of 2020, there were even reports that Trump held discussions in the White House about imposing martial law and seizing voting machines to rerun the election. On Jan. 2, Trump followed this up by berating Georgia’s secretary of state over the phone and urging him to “find votes” for him, a call whose transcript was published and shared widely by The Washington Post. Trump then turned his wrath on his own vice president, arguing that Pence should unilaterally overturn the election results when the Congress met to officially certify them on Jan. 6. When Pence rebuked the president’s request, correctly stating that the US Constitution gave the vice president no ability to overturn the Electoral College results, Trump railed to his supporters at a rally the same day, saying “we will never concede.”

Emboldened by the president’s speech, angry Trump supporters formed a mob that stormed the US Capitol, delaying the official certification process. As the mob clashed violently with Capitol police, Pence and lawmakers had to be evacuated and placed on lockdown. Subsequent videos revealed rioters searching for the vice president and the Speaker of the House while chanting threats to their lives. Five people died in the rioting at the Capitol, including one police officer who was bludgeoned to death. Several pipe bombs were discovered at the Republican and Democratic National Committee headquarters not far from the Capitol, suggesting the events of the day included plans for considerably more destruction. The FBI is investigating the mob violence and has begun to make arrests, while public officials are reviewing the failure of law enforcement to protect Congress from attack. Similar threats of violence on inauguration day have been documented by federal and local law enforcement.

Trump’s refusal to acknowledge his loss is likely to have both short and long-term implications for US politics. In the short term, the most direct effect of his repeated denials has been to impede the transition process for the incoming Biden administration. The first example of this came when Emily Murphy, Trump’s appointed administrator of the General Services Administration, refused to certify Biden’s victory for 16 days after the press called the election. Murphy’s refusal prevented the Biden campaign from receiving the necessary resources and security briefings to officially begin the transition. In the longer term, even though most observers expect Biden’s inauguration to proceed as planned, there is evidence that Trump’s efforts have caused serious harm to the confidence of many of his supporters in the fairness of US elections. The violent storming of the US Capitol building by Trump’s backers on Jan. 6 is likely to further hurt images of US democracy, both at home and abroad.

Biden largely ignored Trump’s efforts at obstruction throughout November and December, and instead pressed ahead with selecting the members of his incoming administration. The announcements thus far suggest that Biden’s Cabinet is set to mark several historic firsts in terms of diversity and representation. Kamala Harris will be the first female, Black, and Asian-American vice president. Elsewhere in the Cabinet, Lloyd Austin has been nominated to be the first Black Defense secretary, Janet Yellen the first female Treasury secretary, Xavier Becerra the first Latino Health and Human Services secretary, Alejandro Mayorkas the first Latino and immigrant Homeland Security secretary, Pete Buttigieg the first openly gay Cabinet member as Transportation secretary, and Deb Haaland the first Native-American Cabinet member as Interior secretary. Biden also elevated individuals with whom he has close relationships to key roles, such as by nominating Antony Blinken as secretary of state and Jake Sullivan as national security advisor.

Joe Biden’s inauguration will take place Jan. 20.

Disconnects in US-Japan Alliance Cooperation?

Presidential transitions in the United States often take time, and alliance management in the interim is largely a task for the bureaucrats and military leaders responsible for the day-to-day oversight of the US-Japan relationship. But the 2020 transition is like no other in recent memory. Moreover, a number of unresolved issues remain for the alliance, born of decisions made in 2020 that suggest a new effort at strategic coordination may be overdue.

First, Japan’s defense thinking seems to be evolving into a more independent mode. The decision to pull back from the deployment of the land-based ballistic missile program AEGIS Ashore has left some in Washington unsure of Japan’s defense plans. A new National Security Strategy is being drafted and is expected in 2021. Also expected is a rewrite of the 10-year defense plan due to increasing pressures on the defense budget. Nonetheless, on Dec. 21, the Suga Cabinet approved a record defense budget of 5.34 trillion yen ($51.7 billion) for fiscal 2021, a 0.5% increase from the year before. The policy discussion on conventional strike capability has been shelved, although many expect it will return after the Lower House election. Japan’s new defense minister, Kishi, has not skipped a beat, however, in increasing investment in Japanese capabilities. On Dec. 18, he announced that Japan would invest in an indigenous standoff missile. This followed on the heels of the announcement last year that Mitsubishi Heavy Industries would take the lead in an international consortium for replacing Japan’s support fighters.

Second, this is a complicated moment for Japan’s diplomacy with China. President Xi Jinping was due to visit Tokyo for a state visit in the spring of 2020, but the pandemic stalled that final step in improving China-Japan diplomacy. Other factors have since come into play. The rising antagonism between Washington and Beijing over the coronavirus, as well as over longstanding trade tensions, has meant little global problem-solving with China is taking place. To make matters worse, China’s imposition last summer of a National Security Law on Hong Kong residents has soured international opinion on Beijing’s ambitions. At the time, Foreign Minister Motegi Toshimitsu issued a statement expressing Japan’s opposition to the law, saying that Japan attaches “great importance to upholding a free and open system and the democratic and stable development of Hong Kong under the ‘one country, two systems’ framework.” The mass arrests of prodemocracy activists and civil society actors in Hong Kong have only made it more likely that Japan’s diplomacy with China will be derailed.

Events across the Taiwan Straits also raised the stakes for the United States and Japan as they seek to cope with China’s challenge. As Taipei and Washington have increased official contacts, Beijing has made escalating demonstrations of military power. On Sept. 18, the National Ministry of Defense in Taipei reported that 18 aircraft, including two H-6 strategic bombers, had intruded into its Air Defense Identification Zone by crossing the median line between the mainland and Taiwan. By year’s end, Reuters reported over 100 sorties by the PLA Air Force across the Straits. Opinion in Tokyo is sensitive to how the new US administration will approach China, and on Dec. 25, the State Minister of Defense Nakayama Yasuhide stated in an interview that the Chinese aggression against Taiwan constituted a “red line” and urged the incoming Biden administration to “be strong” against Beijing. To date, the Japanese government has assiduously avoided any statement that would suggest alliance cooperation with the US in a Taiwan contingency. On Jan. 9, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced that the United States would no longer restrict its diplomatic engagement with Taiwan, creating a difficult dilemma for the incoming Biden administration as it seeks to reset US foreign policy in the Indo-Pacific. Escalating tensions between the United States and China on Taiwan will undoubtedly put Japan’s Taiwan policy to the test.

Finally, domestic politics in both the United States and Japan remain unresolved, despite leadership transitions in Washington and Tokyo. For Japan, the prospect of a Lower House election hovers over the Suga Cabinet. Successfully navigating the pandemic and its economic fallout remains elusive for Suga, as it did for Abe. Moreover, the legacy of Abe’s scandals has left Suga somewhat handicapped. Without demonstrable successes in governance, the LDP’s prospects at the polls may be dimmer. Opposition parties, despite an important merger, are not poised to take power and yet they could offer greater challenge to LDP candidates in the upcoming election if frustrations continue to run high. In the United States, of course, much resets on the ability of the Biden administration to avoid a lengthy and contentious process of confirming nominees for the Cabinet and other senior positions. The victory by the two Democratic candidates in the Georgia Senate race is likely to ease this aspect of the transition. But the United States too is bogged down by the pandemic’s toll, and the Biden administration will be focused like the Suga Cabinet on improving the health and welfare of its citizens. Continued partisan antagonism could also be a factor in Washington’s ability to focus on its foreign policy agenda.

2020 Finally Ends but the Turmoil Does Not

For many, 2020 was a horrific year. Japan and the United States continue to battle the COVID-19 pandemic, and leadership transitions in both nations reveal the growing disgruntlement of the public in the government response. Japan’s political transition from Abe to Suga was unexpected. Rising US domestic tensions over its leadership choice, however, were not. The US-Japan alliance benefitted during these unpredictable Trump years from a highly personalized role for the Japanese prime minister in the execution of alliance cooperation with the United States. Abe, far earlier than other US allied leaders, understood the political benefits to be had from establishing close ties with the mercurial US president. Yet it remains unclear how well he understood the populist impulses, and the dangerous ambition, of Trump.

Deep political divisions in the United States seem destined to continue even after Joe Biden and Kamala Harris are sworn into office on Jan. 20. Few expected Trump’s persistent refusal to accept the election outcome and the continued disinformation about the voting process by elected members of the Congress. Yet, the shock of the mob violence that ensued on Jan. 6 signals a far deeper crisis for US democracy. While the impact on the US-Japan alliance may not be clear, the continued turmoil of US politics is likely to ensure a government in Washington that will find it difficult to focus on events abroad.

The COVID-19 pandemic, of course, continues to wreak havoc in the United States and Japan. Over 300,000 Americans and 3,000 Japanese died from COVID-19 in 2020. Travel between the two countries is restricted, and while the two governments continue to manage their day-to-day relations virtually, the priority for the Suga Cabinet and the incoming Biden administration will be taking care of their citizens at home. 2021 has begun with darker clouds than expected, and until the US transition to a new president has been safely accomplished, it is hard to imagine what might be ahead for the US-Japan partnership in the new year.

Sept. 1, 2020: Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) announces that it will not include votes from rank-and-file members in the party election to decide Abe’s successor.

Sept. 5, 2020: Prime Minister Abe Shinzo says that he will publish a new statement on ballistic missile defense strategy before his planned resignation on Sept. 16.

Sept. 8, 2020: G7 foreign ministers, including from the US and Japan, release a joint statement on the poisoning of Alexei Navalny.

Sept. 8, 2020: The US and Japan release a joint ministerial statement marking the one-year anniversary of the Japan-US-Mekong Power Partnership (JUMPP).

Sept. 14, 2020: Suga Yoshihide is elected LDP president with 377 of 534 votes.

Sept. 16, 2020: Suga takes office as prime minister of Japan.

Sept. 16-17, 2020: Eleventh meeting of US-Japan Policy Cooperation Dialogue on the Internet Economy is held via videoconference.

Sept. 20, 2020: Suga and President Trump speak by telephone.

Sept. 24, 2020: Japan-US Strategic Energy Partnership (JUSEP) meeting is held via videoconference.

Sept. 25, 2020: Deputy Minister for Foreign Policy Yamada Shigeo, Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs David Stilwell, Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Affairs Dean Thompson, Australian Deputy Secretary (Indo-Pacific Group) Justin Hayhurst, Indian Joint Secretary (Americas) Vani Rao, and Indian Joint Secretary (East Asia) Naveen Srivastava hold a quadrilateral Japan-US-Australia-India videoconference.

Sept. 25, 2020: Secretary of State Mike Pompeo meets National Security Secretariat Secretary General Shigeru Kitamura in Washington, DC.

Oct. 1, 2020: A list of the 210 members for Science Council of Japan’s General Assembly becomes public, revealing that Suga refused to appoint six academics.

Oct. 6, 2020: Motegi and Pompeo hold a Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in Tokyo.

Oct. 6, 2020: Pompeo meets with Suga in Tokyo.

Oct. 6, 2020: Suga, Pompeo, Australian Minister for Foreign Affairs Marise Payne, and Indian External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar attend the second Japan-US-Australian-Indian Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in Tokyo.

Oct. 7, 2020: Deputy Director General for North American Affairs Arima Yutaka, Deputy Director General for Defense Policy Taro Yamato, Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Japan and Korea Marc Knapper, and Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for East Asian Security Heino Klinck hold bilateral security discussions by videoconference.

Oct. 13, 2020: US, Japan, Australia, Canada, Italy, Luxembourg, United Arab Emirates, and the United Kingdom sign the Artemis Accords on space exploration and utilization.

Oct. 15-16, 2020: Deputy DG for North American Affairs Arima and Department of State Political-Military Bureau Senior Advisor Donna Welton hold preparatory consultations on Japan-US Host Nation Support.

Oct. 18-21, 2020: Prime Minister Suga visits Vietnam and Indonesia.

Oct. 19-23, 2020: Second Japan-Korea-US Women’s Trilateral Conference is held via videoconference, releasing a joint statement.

Oct. 27-28, 2020: The 57th Japan-US Business Conference is held via videoconference.

Oct. 29, 2020: The US, Japan, Australia, and Palau announce construction of an undersea fiber optic cable to Palau.

Nov. 3, 2020: The US holds presidential, legislative, and state and local elections.

Nov. 3, 2020: Indian, Japanese, Australia, and US begin joint naval exercises in the Indian Ocean as part of the Malabar exercise.

Nov. 7, 2020: Associated Press and other major networks declare Joe Biden the winner of the US presidential election.

Nov. 10, 2020: The US and Japan begin formal negotiations on Host Nation Support.

Nov. 10, 2020: Inaugural Japan-US-Brazil Exchange is held in Brasilia, releasing a joint statement.

Nov. 11, 2020: Biden announces Ron Klain will be his chief of staff.

Nov. 12, 2020: Suga speaks by telephone with President-elect Biden.

Nov. 12, 2020: Suga attends the 23rd Japan-ASEAN Summit Meeting.

Nov. 24, 2020: Biden announces he will nominate Antony Blinken as secretary of state, Jake Sullivan as national security advisor, Alejandro Mayorkas as secretary of homeland security, Avril Haines as director of national intelligence, Linda Thomas-Greenfield as ambassador to the United Nations, and John Kerry as special presidential envoy for climate.

Nov. 24-25, 2020: China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi visits Tokyo to meet Suga and Foreign Minister Motegi.

Dec. 1, 2020: President-elect Biden announces he will nominate Janet Yellen as Treasury secretary.

Dec. 1, 2020: Newspaper reports suggest Biden is considering appointing a White House czar for Asia on the National Security Council.

Dec. 2, 2020: Trilateral Vietnam-US-Japan Commercial Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) Forum is held in Hanoi, releasing a joint statement.

Dec. 3, 2020: Deputy Secretary of State Stephen Biegun and Vice Foreign Minister Akiba Takeo speak by telephone.

Dec. 3, 2020: Commander of US Pacific Fleet Adm. John Aquilino is nominated to be the next commander of US Indo-Pacific Command.

Dec. 7, 2020: Newspapers reports indicate that the Japanese government plans to name Ambassador to South Korea Tomita Koji as the next ambassador to the US.

Dec. 8, 2020: Biden announces he will nominate Lloyd Austin as secretary of Defense.

Dec. 9, 2020: Defense Minister Kishi Nobuo announces that Japan will build two new Aegis ships as an alternative to its cancelled land-based system.

Dec. 10, 2020: Biden announces he will nominate Katherine Tai as US trade representative.

Dec. 11, 2020: The FDA authorizes the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine for emergency use.

Dec. 11, 2020: Supreme Court dismisses Texas lawsuit seeking to overturn the presidential election results in four other states.

Dec. 14, 2020: Electoral College votes to affirm Biden’s win by a margin of 306 votes to Trump’s 232 votes.

Dec. 17, 2020: Pompeo and Motegi speak by telephone.

Dec. 17, 2020: Suga Cabinet announces decision to develop a new long-range missile.

Dec. 18, 2020: Senior officials from the US, Japan, Australia, and India meet by videoconference to follow up on the Oct. 6 quadrilateral meeting.

Dec. 18, 2020: Suga Cabinet approves the building of two new Aegis ships.

Dec. 18, 2020: FDA authorizes Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine for emergency use.

Dec. 25, 2020: Tomita Koji officially named as Japan’s ambassador to the United States, effective the same day.

Jan. 7, 2021: Suga declares state of emergency due to COVID-19 in the Tokyo metropolitan area.