Articles

Several unexpected events during the summer of 2020 confounded US-Japan ties. The COVID-19 pandemic continued to challenge governments in Tokyo and Washington, as the number of infected grew. The scale of the pandemic’s impact was far greater in the United States, with new cases climbing in southern and western states. Japan’s metropolitan centers faced an uptick in cases, but so too did less populated regions. The mortality rate of the United States hovered at 3%, a far more worrisome indicator that the pandemic was far from contained. In contrast, Japan continued to have a relatively low mortality rate of 1.9%.

The impending US presidential election increasingly loomed large. The Democratic and Republican parties convened their conventions, with the first online convention showcased by the Democrats on Aug. 17. President Trump held his convention at the White House on Aug. 24, drawing criticism from his opponents, and while his supporters attended in person, it was a scaled-back version of what had initially been planned. By the end of the summer, polling still showed former Vice President Joe Biden, the Democratic nominee, had the lead. The president’s approval rating remained low due largely to his handling of the coronavirus, with 58% of Americans saying they disapproved of the way Trump has responded to the pandemic in a CNN poll (Aug. 12-15).

On June 23, the Japanese and US governments marked the 60th anniversary of the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security. Yet difficulties in defense cooperation rattled relations. The first was the decision by Japan’s Minister of Defense Taro Kono on June 15 to cancel the deployment of the Aegis Ashore ballistic missile defense system. The decision caught many by surprise and resulted in a broader decision to redraft Japan’s National Security Strategy (NSS) and to review the National Defense Program Guidelines adopted in December 2018. Tensions also grew in base communities, particularly in Okinawa, over increasing cases of COVID-19 infections within the US military stationed in Japan. Nonetheless, the United States and Japan continued to work closely on developing their Indo-Pacific cooperation. Chinese behavior demonstrated Beijing’s assertion of its control over the South China Sea. Moreover, Beijing’s decision on June 30 to impose the National Security Law on Hong Kong created ripple effects across the region as demonstrators and others critical of government were detained and arrested.

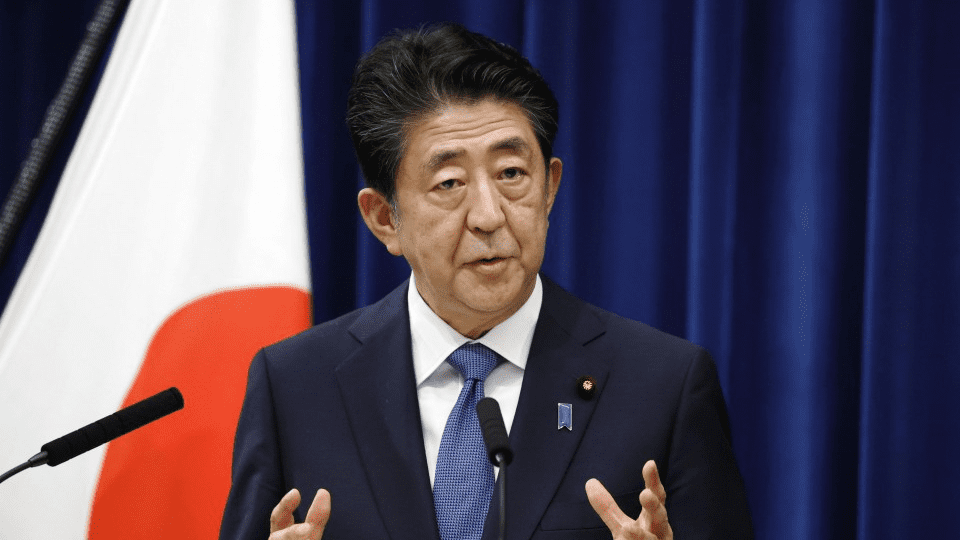

A bigger surprise to the US-Japan relationship came on Aug. 28 when Prime Minister Abe Shinzo announced he would resign. Abe’s relationship with Trump was widely seen as the reason Japan managed to avoid the growing strain between the US and its allies. In a tweet, Trump said that Abe would “soon be recognized as the greatest Prime Minister in the history of Japan, whose relationship with the USA is the best it has ever been.” Abe’s exit, however, raises the question of whether his successor can manage the US-Japan relationship with the same skill.

Japan’s About Face on AEGIS Ashore

Defense Minister Kono Taro announced on June 15 that Japan would suspend deployment of the Aegis Ashore, a sophisticated land-based missile defense system. At a press conference on June 25, Kono then announced that the National Security Council had decided to officially cancel the deployment in Akita and Yamaguchi prefectures. Trouble in Akita began in June 2019 when Ministry of Defense officials responsible for studying how and where the missile defense system would be located in the prefecture incurred the wrath of local residents by misrepresenting the trajectory of GSDF missiles that would shoot down incoming missiles.

Figure 1 Defence Minister Kono Taro announced that Japan would suspend plans for Aegis Ashore. Photo: AP / South China Morning Post

On top of this local concern, the early promise of the Aegis Ashore system was belied by the growing technical capabilities of North Korea, especially the increased maneuverability of its missiles. Furthermore, consultations with the United States suggested it would take more time than originally planned to adapt the system to Japan’s demands. Ultimately with the prime minister’s approval, Kono decided that the estimated $4.1 billion cost of this new BMD system, designed to augment the sea-based Aegis system operated by the Maritime Self-Defense Force, was too great given its limitations in meeting Japan’s growing defense needs. Kono noted that Japan had already spent $1.02 billion on development, which he hoped could be repurposed toward other objectives. Other weapons systems, such as the purchase of Global Hawk unmanned surveillance aircraft, also came under review.

But Kono did not stop at canceling this weapons system. After consultations with the LDP’s defense experts, he recommended larger changes to Japan’s defense policy. The Abe Cabinet announced it would rewrite Japan’s National Security Strategy, which was adopted in 2013 during the first year of the Abe’s return to the kantei. With the marked improvement in North Korean nuclear and missile capabilities, the Cabinet decided it was also time to re-evaluate Japan’s National Defense Program Guidelines and Mid-Term Defense Program, both adopted in 2018. Some in the LDP suggested the time had come to move beyond sole reliance on missile defenses and to seriously consider acquisition of an offensive strike option, an idea that had been proposed in 2017 by the LDP’s Research Commission on Security. The Abe Cabinet ordered a full review of Japan’s military planning to be completed by the end of 2020. On Sept. 5, Abe further said that he would publish a new statement outlining his strategy on ballistic missile defense before his planned resignation on Sept. 16.

US Forces in Japan faced growing Japanese criticism of their management of the coronavirus. By May 25, Japan had lifted its state of emergency as COVID-19 seemed to be contained. However, US Forces Japan had its own public health emergency status. Initially declared on April 6 for US bases in the Kanto area, the public health emergency was expanded to all US military installations in Japan on April 15 and then repeatedly extended over the summer. On July 11, Okinawa Governor Denny Tamaki spoke out against the large number of COVID-19 cases on US bases in his prefecture. While the US military said both Futenma and Camp Hansen had been placed on lockdown, Tamaki expressed “grave doubts” over whether the military had taken adequate steps to prevent US Marines from spreading COVID-19 off base. The number of confirmed cases among US military personnel rose from 45 on July 11 to 62 by July 12, 94 by July 13, and 201 by July 24. After the Japanese government urged them to conform to its protocols on quarantine for those arriving in Japan, US Forces Japan announced on July 24 that all arriving personnel must undergo mandatory testing before being released from two weeks quarantine. Five days later, a joint press statement was issued describing how the Japanese government and US Force Japan would cooperate on COVID-19 efforts. On Aug. 12, US Forces Japan once again extended its public health emergency for Japan for another month.

With these tensions in the relationship, in a rare in-person meeting, Kono flew to Guam to meet US Secretary of Defense Mark Esper on Aug. 29. Consultations on Japan’s purchase of 105 F-35 joint strike fighters moved forward, with US approval issued on July 9. Notable too was deepening US-Japan cooperation in space. On the civilian side, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine and Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Hagiuda Koichi signed the Joint Exploration Declaration of Intent for cooperation on space exploration. Equally important, military cooperation in space, one of Abe’s priorities, continued to move ahead. The US Chief of Space Operations, Gen. John Raymond, visited Tokyo in late August, and met Abe in addition to civilian and uniformed leaders at the Ministry of Defense.

The influence of Abe on Japan’s defense preparedness and on the US-Japan alliance cannot be overstated. Just ahead for Tokyo and Washington are the potentially difficult negotiations over Host Nation Support. Trump’s insistence that US allies do not do enough for their own defense has already had considerable impact on NATO as well as the US-ROK alliance. The US election will undoubtedly frame how Washington responds to Japan’s efforts to realign and strengthen the SDF’s force posture.

China Raises the Stakes for the Alliance

Over the summer, the United States and Japan increased their cooperation in the Indo-Pacific. Efforts to build a coalition of like-minded maritime powers to ensure freedom of navigation across the region stepped up as Chinese military activities also grew. In July, the MSDF and US Navy joined their counterparts from Australia for a trilateral exercise in the Philippine Sea. Capt. Sakano Yusuke, commander of the MSDF’s Escort Division 4, emphasized that “strengthening cooperation with the US Navy and Royal Australian Navy is vitally important for Japan, and also contributes to a free and open Indo-Pacific in the region.” Likewise, Capt. Russ Caldwell, commanding officer of the USS Antietam, noted that the “United States is fortunate to routinely operate alongside its allies across the Indo-Pacific, [as] coordinated operations like these reinforce our mutual commitments to international maritime norms and promoting regional stability.”

Growing Chinese pressure on Taiwan also prompted greater US-Japan maritime collaboration, including a major exercise from Aug. 15-19, in the East China Sea and the Philippine Sea. The USS Ronald Reagan Carrier Strike Group joined the Japanese destroyer JS Ikazuchi for the operations, which involved integrated flight operations, maritime defense exercises, and tactical training. At the same time, the United States organized the 10-country Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercises off Hawaii from Aug. 17-31, which included participation by Japan. While some drills had to be scaled back due to the pandemic, the exercises still involved approximately 5,300 personnel from these 10 countries. Vice Adm. Scott Conn, commander of the US 3rd Fleet and leader of RIMPAC 2020, said at the conclusion of the exercises that the “diverse range of knowledge and professionalism” among navies is what “makes us stronger, and allows us to work together to ensure a free and open Indo-Pacific and ultimately, our collective prosperity.”

Figure 2 The USS Essex arrives in Hawaii for RIMPAC 2020. Photo: US Navy

Chinese behavior in and around Taiwan and its decision to impose the National Security Law on Hong Kong prompted more coordination on China policy. Beijing’s growing pressure on Taiwan drew a series of steps from the Trump administration to signal the US commitment to peaceful cross-strait relations and to bolster Taipei. On Aug. 10, Secretary of Health and Human Services Alex Azar visited Taipei to discuss the COVID-19 pandemic, the highest-level US government official to visit, and met President Tsai Ing-wen. Washington has openly expressed interest in a bilateral trade agreement with Taiwan, rounding out its emphasis on the importance of Taiwan to US interests. Furthermore, on Aug. 31, the American Institute on Taiwan released declassified documents on the Six Assurances offered to Taipei during the Reagan administration. While the content of these documents had been well-known, Assistant Secretary of State for East Asia David Stilwell noted that “it is important to review history like this because Beijing has a habit of distorting it … The fundamental US interest is that the Taiwan question be resolved peacefully, without coercion, in a manner acceptable to the people on both sides of the Strait—as Beijing promised.”

Although Japan did not offer an official comment on Azar’s visit or the release of the declassified documents, newspaper reports cited an anonymous source from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs who on Aug. 10 said that Japan would continue to support Taiwan through “available means.” Earlier, on May 20, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs had expressed support by referring to Taiwan as an “extremely important partner” in the annual Diplomatic Bluebook, which represented stronger language than the previous year’s description of Taiwan as a “crucial partner and an important friend.”

Beijing’s decision to impose its National Security Law on the citizens of Hong Kong invited a strong rebuke by both Washington and Tokyo. The Abe Cabinet had postponed a state visit by Chinese President Xi Jinping to Japan due to the pandemic. But the announcement of China’s intention to crack down on Hong Kong’s prodemocracy movement prompted a backlash against the visit. Government statements grew increasingly critical. Initially, Foreign Minister Motegi Toshimitsu noted the reports of China’s intentions as suggesting that if true, “then it is regrettable that it was enacted despite the strong concerns of the international community and the people of Hong Kong.” Later, Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga Yoshihide stated that imposition of the law “undermines the credibility of the “one-country, two-systems” principle. On July 7, after the enactment of the law, the Liberal Democratic Party adopted a resolution against Xi’s visit.

The Trump administration and the US Congress were more forceful in their condemnation. As early as May 22, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo warned of punishment and said that the proposed security measure would be a “death knell” for Hong Kong’s political freedoms. On June 30, Pompeo condemned the newly enacted law by saying that “the Chinese Community Party’s decision to impose draconian national security legislation on Hong Kong destroys the territory’s autonomy and one of China’s greatest achievements.” On July 1, the House of Representatives passed the Hong Kong Autonomy Act by unanimous consent, requiring the Department of State to report annually to Congress on “foreign individuals and entities that materially contributed to China’s failure to comply with the Joint Declaration or the Basic Law” and on “foreign financial institutions that knowingly conducted a significant transaction with such identified individuals and entities.” On July 2, the Senate likewise approved the bill by unanimous consent. On July 14, by Executive Order 13936, Trump revoked Hong Kong’s special trading and economic status with the United States and signed the Hong Kong Autonomy Act into law. On Aug. 7, the Department of Treasury designated 11 individuals under the Executive Order.

The United States and Japan will need to further coordinate China policy as the US-China confrontation intensifies. Others in Asia are also taking a far more confrontational tack with Beijing, most notably Japan’s close partner, Australia. Tokyo remains more comfortable aligning with other partners in multilateral settings. For example, China’s announcement of the imposition of the National Security Law on Hong Kong prompted a strongly worded statement of condemnation by G7 foreign ministers on June 17, including Motegi and Pompeo. The foreign ministers said that they were “extremely concerned” that the action would threaten Hong Kong’s autonomy, rule of law, and the “fundamental rights and freedoms” of its people as they urged China to reconsider the decision. With the impending leadership transition in Tokyo, and possibly in the United States, a far more concrete alliance agenda for dealing with the many challenges posed by China will be required.

Abe’s Resignation and the US-Japan Relationship

Abe was remarkable among allied leaders in his approach to, and subsequent friendship with, Trump. Abe met with president-elect Trump at Trump Tower the week after the election in November and he was the first foreign leader to officially visit President Trump in February 2017, the month after his inauguration. Abe met with Trump at the White House, with the two leaders issuing a joint statement on the importance of the bilateral relationship, but he also enjoyed a weekend of golf with Trump at the president’s Mar-A-Lago resort in Florida. In May 2019, Trump visited Japan and became the first world leader to meet the new Emperor Naruhito and Empress Masako. Abe’s close, personal relationship with Trump also helped him to handle Trump’s insistence on a bilateral rather than multilateral trade agreement. The two leaders concluded a limited trade deal in September 2019 and agreed to begin negotiations on a more comprehensive pact. In doing so, Abe managed to avoid Trump’s threat of higher tariffs on Japanese automobiles, which would have been devastating for the Japanese economy.

Figure 3 Prime Minister Shinzo Abe announces his intention to step down. Photo: Kyodo

Abe was also deft at navigating around the mercurial president. While Trump officially withdrew the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) as soon as he entered office in 2017, Abe continued to be a fierce proponent of free trade. In 2018, Japan signed two landmark free-trade agreements: the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPPP), without US participation, and the even larger Japan-European Union trade deal. Abe also proved to be effective in asserting Japan’s interests in other multilateral settings, such as encouraging greater cooperation among the members of the UN Security Council in enforcing compliance on sanctions against North Korea. Similarly, as tensions between Washington and Beijing grew, Abe continued the slow but important effort to find common cause with China in building a more open regional order. Although derailed by COVID and then by China’s crackdown in Hong Kong, the carefully calibrated summitry between Abe and Xi contrasted markedly with the increasingly hostile tone of US-PRC relations.

At home, Abe remained popular throughout much of his tenure as Japan’s longest-serving prime minister, though his approval ratings suffered at times from allegations of corruption and more recently from criticism over his handling of the coronavirus pandemic. Even though Japan fared much better than many other countries, including the United States, citizens in Japan gave the Abe administration low marks for its handling of the country’s response. Critics worried that Abe was prioritizing the economy, already in recession, at the expense of public health. Policies such as the 1.35 trillion yen ($12.7 billion) Go-to-Travel program, which offered travel subsidies to encourage domestic tourism within Japan, came under criticism as the number of COVID-19 cases began to surge. In August, Abe’s approval rating fell to its lowest level (NHK: 34%) on the eve of his resignation. The same poll found that 58% disapproved of the government’s handling of the pandemic, with 57% saying that Abe should declare a second state of emergency.

As the Abe Cabinet struggled to win popular support for its COVID-19 response, many local leaders in Japan gained popularity for implementing stronger measures to bring the coronavirus under control. Governor of Tokyo Koike Yuriko in particular emerged as a strong critic of Abe, taking on a role that some observers likened to the clash between New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo and Trump. Unlike Abe, Koike received high praise from Tokyoites for her daily video briefings, approachable style, and tougher stance on reopening businesses or promoting travel. On July 5, she easily won re-election with 59.7% of the vote. Apart from Koike, other governors in Japan have also received strong support in their prefectures for defying the central government by issuing their own coronavirus policies, including Nisaka Yoshinobu in Wakayama, Suzuki Naomichi in Hokkaido, Omura Hideaki in Aichi, Yoshimura Hirofumi in Osaka, and Tamaki in Okinawa. However, there have been some missteps at the local level as well, such as when Yoshimura came under fire for suggesting that a gargling medicine could help patients with the coronavirus.

The era of Abe-Trump will come to a close when a new president of the LDP is chosen. All three candidates are well known in Washington, and all are deeply steeped in the workings of the US-Japan alliance. Ishiba Shigeru worked closely with the Bush administration when he was minister of Defense from 2007 to 2008. His position as secretary-general of the LDP from 2012 to 2014 also contributed to Japan’s political relations with the United States. Kono Taro, now defense minister, was Japan’s minister of Foreign Affairs from 2017 to 2019. Coming from Kanagawa Prefecture, Kono has a keen interest in ensuring that implementation of the Status of Forces Agreement does not come at the expense of the communities that host US forces. Finally, the most likely candidate to succeed Abe, Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga Yoshihide, has had ample exposure to the US-Japan relationship during both the Obama and the Trump presidencies. Suga visited Washington in May 2019 to meet Vice President Mike Pence and Pompeo.

Looking Ahead

National responses to the COVID-19 pandemic continue to consume Tokyo and Washington, and yet foreign and security cooperation in the US-Japan alliance needs considerable policy attention. From how to ensure deterrence against the growing missile threat to Japan to the conspicuous signs of a far more challenging Chinese military in the Indo-Pacific, the United States and Japan must organize themselves far more effectively if they are to shape the military balance in the region. The Japanese decision to revamp its missile defenses and its overall National Security Strategy this fall could falter as both governments face political transitions. To be sure, Abe’s emphasis on strengthening Japan’s defenses, including the US-Japan alliance, will not be abandoned by his successor. Yet there is an increasing sense that the alliance needs greater political stewardship in Washington to keep the United States and Japan on track to cope with fast-paced military changes in the region.

The US presidential election, of course, looms large. Will it be a Trump administration 2.0, and if so, who will assume the critical national security portfolios in a new Cabinet? With Abe gone, can the alliance receive the same level of presidential attention it did during his time in office? Japan and the United States will begin sensitive negotiations on Host Nation Support soon, and the worry in Tokyo is that it could raise domestic political tensions over the alliance as similar US-ROK talks did in South Korea. Getting the Trump administration’s nominee for US ambassador to Japan, the Hudson Institute’s Kenneth Weinstein, confirmed by the Senate would help ease the prospect of a disconnect on Host Nation Support.

A new US president would, of course, bring new issues to the fore. The lengthy process of nominating and confirming the Cabinet and a Biden presidency’s Asia team would likely postpone strategic coordination. The traditional worry in Tokyo continues to be that a new Democratic administration, especially if backed up by a more progressive Democratic Party in the House and Senate, could have a far different foreign policy agenda. But until Japan’s approach to China policy is reset, it will be hard to predict whether Tokyo and Washington can synchronize actions vis-à-vis China. Military cooperation will likely continue apace, and cooperation with Australia and India across the Indo-Pacific region is likely to continue or even increase. Yet Japan’s economic investment in China could take longer to adapt.

May 8, 2020: Okamoto Yukio, veteran diplomat, adviser to prime ministers, and staunch advocate for the US-Japan alliance, passes away at the age of 74.

May 8, 2020: President Trump and Prime Minister Abe Shinzo speak by phone about COVID-19.

May 11, 2020: Minister of Foreign Affairs Motegi Toshimitsu and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo participate in a teleconference on COVID-19 with foreign ministers of Australia, Brazil, Israel, India, and South Korea.

May 12, 2020: US Forces Japan extends public health emergency in Japan until June 14, 2020.

May 20, 2020: Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ annual Diplomatic Bluebook describes Taiwan as an “extremely important partner,” a stronger description than the previous year’s description of a “crucial partner and an important friend.”

May 22, 2020: Pompeo warns China of punishment if it goes ahead with the planned security law for Hong Kong.

May 25, 2020: Abe lifts the state of emergency for COVID-19.

June 15, 2020: Defense Minister Kono Taro announces that Japan will suspend deployment of the Aegis Ashore ballistic missile defense system.

June 17, 2020: Pompeo and Motegi join G7 foreign ministers in issuing a joint statement of concern for China’s national security law in Hong Kong.

June 23, 2020: Japan and the United States mark the 60th anniversary of the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security entering into force.

June 25, 2020: Kono announces that the National Security Council has decided to cancel deployment of the Aegis Ashore ballistic missile defense system in Yamaguchi and Akita prefectures.

June 30, 2020: Pompeo condemns China over Hong Kong’s national security law.

June 30, 2020: Chinese President Xi Jinping signs a new security law for Hong Kong.

July 1, 2020: US House of Representatives passes the Hong Kong Autonomy Act by unanimous consent.

July 2, 2020: The US Senate approves the Hong Kong Autonomy Act by unanimous consent.

July 5, 2020: Koike Yuriko wins reelection as governor of Tokyo.

July 7, 2020: Liberal Democratic Party adopts a resolution against Xi’s visit to Japan.

July 9, 2020: United States approves Japan’s planned purchase of 105 F-35 joint strike fighters.

July 9, 2020: NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine and Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology Koichi Hagiuda sign Joint Exploration Declaration of Intent on space cooperation.

July 9, 2020: US Forces Japan extends public health emergency in Japan until Aug. 13.

July 9-10, 2020: Deputy Secretary of State and Special Representative for North Korea Stephen Biegun travels to Tokyo to meet Motegi, Kono, Vice Foreign Minister Akiba Takeo, and other officials.

July 11, 2020: Okinawa Gov. Denny Tamaki calls the large number of COVID-19 cases at US bases in Okinawa “extremely regrettable” after being notified by the US military that the number of confirmed cases had risen to 62.

July 13, 2020: The US Marine Corps in Okinawa officially reports 94 confirmed cases of COVID-19 to the prefectural government.

July 14, 2020: Trump issues Executive Order 13936 revoking Hong Kong’s special trading and economic status with the United States and signs the Hong Kong Autonomy Act into law.

July 19, 2020: Maritime Self-Defense Force, Australian Defense Force, and US Navy begin a trilateral exercise in the Philippine Sea.

July 23, 2020: Pompeo delivers a speech on China at the Nixon Library.

July 24, 2020: US Forces Japan announces that all arriving personnel must undergo mandatory COVID-19 testing before being released from two weeks of quarantine.

July 29, 2020: Government of Japan and United States Forces Japan issue joint press release on their efforts to combat COVID-19.

Aug. 3, 2020: Department of State appoints Donna Welton as senior advisor for security negotiations and agreements, where she will lead negotiations over the costs of stationing US forces in Japan.

Aug. 5, 2020: US Ambassador to Japan nominee Kenneth Weinstein testifies before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

Aug. 7, 2020: US Department of Treasury designates 11 individuals under Executive Order 13936.

Aug. 10, 2020: Secretary of Health and Human Services Alex Azar visits Taipei to discuss the COVID-19 pandemic and meet with President Tsai Ing-wen.

Aug. 12, 2020: US Forces Japan extends public health emergency for Japan until Sept. 12, 2020.

Aug. 13, 2020: Newspaper reports suggest that the Japanese government may abandon its plan to buy three US-made Global Hawk surveillance aircrafts.

Aug. 15-19, 2020: The US Navy and Maritime Self-Defense Force conduct joint operations in the East China Sea and Philippine Sea.

Aug. 17-20, 2020: The Democratic National Convention convenes in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Aug. 17-31, 2020: Maritime Self-Defense Force participates in the US-led, 10-country Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercises off the coast of Hawaii.

Aug. 24-27, 2020: Republican National Convention convenes in Charlotte, NC and Washington, DC.

Aug. 27, 2020: Abe meets with Chief of Space Operations General John Raymond in Tokyo.

Aug. 28, 2020: Abe announces that he will resign because of ill health.

Aug. 29, 2020: Secretary of Defense Mark Esper and Kono meet in Guam.

Aug. 31, 2020: Abe and Trump speak by telephone.

Aug. 31, 2020: The American Institute in Taiwan declassifies documents on the Six Assurances offered to Taipei during the Reagan administration.

Sept. 1, 2020: The Liberal Democratic Party announces that it will not include votes from rank-and-file members in the party election to decide Abe’s successor.

Sept. 5, 2020: Abe says that he will publish a new statement on ballistic missile defense strategy before his planned resignation on Sept. 16.