Articles

Beginning in 2000, and in almost every year since, Comparative Connections has carried an annual assessment of India-East Asia relations; on occasion this assessment has been combined with one on India-United States relations. The approach to this series of articles has been to review India’s relations with East Asia’s individual countries and subregions such as Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands. This year our annual assessment of India-East Asia relations takes a new approach: assessing India’s involvement and integration with East Asia thematically (diplomacy, defense, trade/investment and multilateralism) incorporating updates on select/relevant countries during 2018. The impetus to the change is to arrive at a better appreciation of the most important elements of India’s involvement and integration into East Asia’s diplomatic, defense-security, and economic environment.

East Asia in India’s foreign, defense and commercial policies

India is engaged globally via a number of overlapping conceptions, initiatives, interests, and policies as might be expected of a country of its size, population, economy, military and foreign policy traditions.

As I have argued in Weighted West, Focused on the Indian Ocean and Cooperating on the Indo-Pacific: The Indian Navy’s New Maritime Strategy, Capabilities and Diplomacy, India’s key major foreign policy, economic, and security interests are “weighted west” and concentrated in the Indian Ocean even as the country’s diplomatic, security, and commercial engagements have expanded across the Indo-Pacific region, especially in East Asia. Importantly, India’s foreign policy and naval functional and regional interests have converged significantly, and the Navy has become an important defense and diplomacy tool in India’s “Act East” policy. This trend, a few years running, was especially pronounced in 2018.

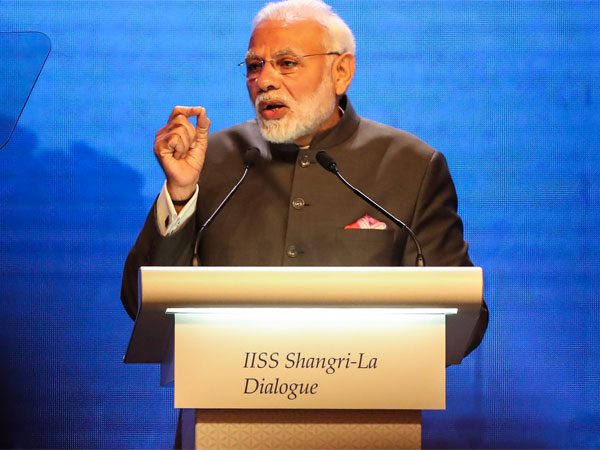

Prime Minister Narendra Modi giving the keynote address at the June 2018 Shangri-La Dialogue. Photo: One India

India recently also has sought to link specific foreign policy initiatives to its expanding East Asia engagements. For example, during Indian President Ram Nath Kovind’s visit to Myanmar in December 2018, he highlighted “synergies between Myanmar’s independent, active and non-aligned foreign policy and India’s pragmatic Act East and Neighbourhood First policies.” And Prime Minister Narendra Modi, giving the keynote address at the June 2018 Shangri-La Dialogue articulated his SAGAR (Security and Growth for All in the Region) initiative as “the creed we follow to our East now even more vigorously through our Act East Policy by seeking to join India, especially her East and North-East, with our land and maritime partners to the East.”

The conceptual application by India of its other foreign policy initiatives such as “Neighborhood First” and SAGAR to “Act East” which is focused on East Asia signifies a continued effort to deepen and expand its engagement with the region. Tenuous as the specific synergies might be for driving India-Myanmar relations, and the paucity of evidence that SAGAR as an initiative has practical application to India’s East Asia relationships, the fact that the president and prime minister sought to highlight these linkages speaks to an effort to place India’s East Asia efforts in the context of its primary conceptions and initiatives of foreign policy – something akin to internalizing the externality of East Asia in India’s international relations.

India’s diplomatic engagement with East Asia

As the India-East Asia relations articles in this series have shown, since the initial “Look East” policy was launched in 1992 India has increased and enhanced its diplomatic ties with East Asia beginning with “first-ever visits,” proceeding to institutionalizing regular interactions, establishing and then upgrading frameworks for cooperation, and more recently building a set of mechanisms for moving forward with specific elements of cooperation across diplomatic, security, and commercial domains. Inevitably, some diplomatic ties have progressed further and faster than others. This pattern largely continued in 2018 and reflected India’s aspirations and activities for a greater diplomatic role in East Asia.

However, India’s diplomatic engagements in East Asia must still compete with other regions and even in East Asia itself they are fitful and episodic. For example, India’s Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) officials, in a briefing about President Kovind’s November visits to Vietnam and Australia noted that this is first time “he is travelling to an ASEAN country, it is also the first time he is travelling to the East of India in capacity as the President of India. His visits so far have been to the West, they have spanned the Western Indian Ocean right up to the Atlantic. This visit will take him right up to the heart of the Indo-Pacific region.” And External Affairs Minister (EAM) Sushma Swaraj noted during her August visit to Hanoi that this was her first visit to the country after a gap of four years.

Despite these limitations, the seniority and scope of India’s East Asia diplomacy during the year was quite robust. Prime Minister Modi’s decision to accept an invitation to give a keynote speech at the Shangri-La Dialogue, the first Indian prime minister to do so, indicated at a minimum a desire to project India as a player in the Indo-Pacific. The fact that India’s MEA meticulousness about protocol was relaxed to have the prime minister speak at a gathering meant for defense ministers also gave the decision significance.

The most significant diplomatic event of India-East Asia relations in 2018 was the India-ASEAN Commemorative Summit and the 25th Anniversary of ASEAN-India Dialogue Relations under the theme of “Shared Values, Common Destiny” held in New Delhi on Jan. 25, 2018. All heads of ASEAN member countries traveled to India to participate and as a group were “Chief Guests” of India’s Republic Day parade. During the event, a “Delhi Declaration” was issued, providing both a review and framework for future cooperation. This event was the culmination of an effort by India to engage all 10 ASEAN member countries since Prime Minister Modi took office in 2014. As an MEA official explained, “in the last four years we have had visits to all the 10 ASEAN countries at the highest level, i.e., at the level of our President, Vice President and our Prime Minister who have covered all the ten ASEAN countries.” As of 2018, “India and ASEAN have 30 dialogue mechanisms cutting across various sectors and operating at various levels that meet regularly. This includes a Summit and 7 Ministerial meetings in Foreign Affairs, Defence, Commerce, Agriculture, Environment, Renewable Energy and Telecommunications.”

India-Southeast Asia ties did not end with the January extravaganza. Other leader-level exchanges included Cambodia Prime Minister Hun Sen’s state visit in January and Vietnam’s President Tran Dai Quang’s state visit in March. Prime Minister Modi visited Indonesia in May, his first visit to the country since taking office in May 2014. Also in May, PM Modi briefly stopped in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia to meet newly-elected Prime Minister Mahathir Mohammad. Modi continued his focus on Southeast Asia with his second visit to Singapore at the end of May and early June including the keynote speech at the 17th Shangri-La Dialogue. The prime minister ventured to Singapore yet again in mid-November for the second RCEP Summit, 16th ASEAN-India Breakfast Summit, and the 13th ASEAN Summit. President Kovind also kept up the diplomatic pace with Southeast Asia, closing out the year with a November visit to Vietnam and a December state visit to Myanmar. Other officials from India and Southeast Asia supplemented these leader-level visits that are summarized in the chronology accompanying this article. Looking ahead, 2019 is labelled the year of tourism between India and ASEAN.

Elsewhere in East Asia, Prime Minister Modi made a visit to China in April for a new diplomatic innovation labelled an “Informal Summit” – though it is questionable just how informal a summit could be between the leaders of the world’s two largest, nuclear-armed countries whose militaries had just faced off on the Doklam Plateau, including a bout of unarmed jostling and rock throwing. The trip achieved little beyond platitudes in the way of resolving the specific dispute or improving India-China relations. But relations did not get worse or break into open conflict. In fact, there is evidence to support the view that China has not altered its longer-term strategic objectives in the region and India, for a mix of motives, has chosen to respond in a measured way.

In June, Prime Minister Modi again traveled to China, this time Qingdao, to attend the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) Summit, the first occasion on which India attended as a full member rather than observer. During this visit, Modi also had an hour-long bilateral meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping. Importantly, an MoU was signed on “provision of hydrological information of the Brahmaputra river in flood season by China to India” that “enables the Chinese side to provide hydrological data in flood season from 15th May to 15th October every year. The Article also enables the Chinese side to provide hydrological data if water level exceeds mutually agreed level during non-flood season.” Earlier, during an April 22 visit to Beijing by EAM Sushma Swaraj for talks with State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi and to attend the Shanghai Cooperation Organization’s Council of Foreign Ministers, India expressed “appreciation to the Chinese side for their confirmation on resumption of data sharing on Brahmaputra and Sutlej rivers in 2018, as this issue has direct relevance for people living in those areas.” This data sharing had been suspended by the Chinese side in the wake of the Doklam faceoff in December 2017.

Prime Minister Modi travelled to Tokyo in late October to meet Prime Minister Abe as part of annual leader-level meetings between the two countries. The main features of this meeting were a 25-point Joint Vision Statement and a set of 12 Facts Sheets on the relationship. A number of announcements and agreements were announced ranging from Japan becoming the 71st country to join India’s International Solar Alliance (ISA) and an “implementing arrangement for deeper cooperation between Japan Maritime Self-Defence Force and Indian Navy.”

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and his Indian counterpart, Narendra Modi, shake hands in a photo session at a luncheon at a resort hotel near Mount Fuji. Photo: Japan Times

There were also important visitors from East Asia to India. In July the Republic of Korea’s President Moon Jae-in made a state visit to India and in November Korea’s First Lady Kim Jung-sook made her own visit.

In a year in which there was significant discussion of the so-called “Quad” or quadrilateral meeting among the US, Japan, India, and Australia, President Kovind visited Australia in November, the first-ever visit by an Indian president and following on the first visit of an Indian prime minister to Australia in 30 years in 2014 when Modi visited. Such visits were a reminder that for all the excitement about the quad, at least one side of the square is still quite fresh and developing in a steady but thin manner – the India-Australia side.

As the mutual exchange of leader-level and senior officials visits suggest, by most measures India-East Asia diplomatic engagements in 2018 were considerable if not precedent-setting.

India’s defense & security relations with East Asia

India continued in 2018 to build on its defense and security ties with select East Asian countries and speak to broader security issues and developments in the Indo-Pacific region, including the US’ own articulation of free and open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) policies.

Prime Minister Modi’s June 2018 Shangri-La speech was an important indicator of India’s positions. First, he repeatedly used the word “inclusive” to indicate that India’s regional approach was not intended to exclude China. Indeed, if the Trump administration’s FOIP mean “free and open Indo-Pacific” then India’s counter acronym could be labeled as “free and inclusive Indo-Pacific.” India’s efforts throughout the year to manage and tone down frictions with China reinforced this inclusive message. On breathless discussions about the Quad, India poured lukewarm water; with PM Modi saying “[w]e will work with them, individually or in formats of three or more, for a stable and peaceful region. But, our friendships are not alliances of containment.” India’s MEA officials were even more unenthusiastic, saying when it comes to “…quad, let me say that India engages with countries in different formats and with many countries at the same time as well. We meet at bilateral levels, we meet at trilateral levels, we meet in quadrilaterals, we meet in pluri-lateral and we meet in multilateral formats. So this quad meeting is something which is going to take place but it has got nothing to do with the East Asia Summit. It is a meeting which takes place at the official functional level between the four countries and the agenda there normally is to look at how we can look at peace and prosperity issues in the region.”

Prime Minister Modi himself gave primacy to maritime and naval engagement in India’s East Asia security, military, and defense relations. Speaking at Shangri-La, he said “India Armed Forces, especially our Navy [emphasis added], are building partnerships in the Indo-Pacific region for peace and security, as well as humanitarian assistance and disaster relief.” And the defense diplomacy component was visible in ship visits coordinated with the prime minister’s travels.

Throughout the year, defense cooperation focusing on the maritime domain were featured in bilateral relationships between India and East Asia. For example, in the January India-Cambodia joint statement “The Prime Minister of India highly appreciated Cambodia for hosting the goodwill visits of Indian ships for three consecutive years starting from 2015 to 2017.” Notably the joint statement referred to both India and Cambodia’s “support [for] complete freedom of navigation and overflight and pacific resolution of maritime issues based on international law, notably the1982 UNCLOS.” Given Cambodia’s role in seeking to derail ASEAN pushback against China’s assertiveness on the South China Sea issue, the inclusion of the language was notable.

India-Indonesia defense and security relations also advanced during the year with PM Modi himself highlighting them in his prepared remarks at Shangri-La. He noted that since 2005 Jakarta and New Delhi have had a strategic partnership and in 2018 held the first security dialogue via visits by India’s external affairs minister and national security advisor. Modi did not explain why a strategic partnership launched in 2005 took until 2018 to begin a security dialogue or why four years elapsed before his first visit to Indonesia. Nevertheless, during his May visit the two sides agreed to move from a “strategic partnership” to a “comprehensive strategic partnership” and issued a “Shared Vision of India-Indonesia Maritime Cooperation in the Indo–Pacific,” which called for the two sides “to take necessary steps to enhance connectivity (institutional, physical, digital and people-to-people) between Andaman and Nicobar Islands of India and provinces in Sumatera Islands of Indonesia to promote trade, tourism and people-to-people contacts; facilitate B to B linkages between the Chamber of Commerce of Andaman and the ones of the Provinces in Sumatera, including Aceh.” And the Joint Statement issued during the visit stated that the two sides “appreciate the decision to set up a Joint Task Force to undertake projects for port related infrastructure in and around Sabang” and “welcome the plan to build connectivity between Andaman Nicobar – Aceh to unleash the economic potentials of both areas.”

With Vietnam, too, India’s defense cooperation progressed and still seems a priority, indicated by the fact that it is the first subject heading in the November 2018 joint statement. The two countries agreed, during a March 2018 state visit to India by President Quang, “to operationalise the Memorandum of Understanding signed between the National Security Council Secretariat of India and the Ministry of Public Security of Viet Nam and initiate the Deputy Ministerial level dialogue to enhance cooperation in traditional and non-traditional security matters and undertake training and capacity building programmes.” Specifically regarding maritime issues, the “two sides agreed to further promote Viet Nam-India bilateral consultation” and “strengthen cooperation in the maritime domain including anti-piracy, security of sea lanes, exchange of white shipping etc… and further encouraged port calls of each other’s naval and coast guard ships.” During an August visit by India’s EAM to Hanoi it was agreed that “it is essential to strengthen our cooperation in maritime domain and [they] decided to hold the first Bilateral Maritime Security Dialogue later in 2018.” This was later pushed back to early 2019 as President Kovind told Vietnam’s National Assembly.

However, on the two credit-lines provided by India for use by Vietnam, no major progress appears to have been made. In the joint statement during President Qang’s March 2018 visit “The Indian side affirmed its continued willingness to partner with Viet Nam in defence cooperation and in building capabilities and capacities for Viet Nam. Both sides agreed to expedite the implementation of the US$100 million Line of Credit for building of high-speed patrol boats for the Viet Nam Border Guards and urged for early signing of a framework agreement on the US$ 500 million Line of Credit for defence industry.” The language indicates that neither line of credit is being utilized – or at least not fully. There has been speculation that the $500 million LoC was for the purchase of Indian missiles but when asked at press brief about the Aakash and Brahmos missiles, the Indian spokesperson said “I would not get into the details but what you have mentioned is something that these aspects are not in the agenda now with Vietnam.” The joint statement issued at the end of Modi’s visit in November seemed to imply that it was Hanoi that needed to move on utilization of the $500 million line of credit: “The Vietnamese side appreciated India’s offer of the US$500 million Line of Credit to defence industry and agreed to accelerate procedures for its approval.”

India-Japan defense and maritime cooperation in particular was highlighted during the year though no new major developments were reported and earlier reports about possible sales of Japan’s US-2 reconnaissance planes went mostly unmentioned – suggesting that no progress has been made. According to an India-Japan Defense and Security Fact Sheet and a Joint Vision Statement issued on Oct. 29 at the conclusion of PM Modi’s visit, the two sides expressed “great satisfaction with the enormous progress made in the last decade in fostering joint efforts towards shared security since the signing of the India-Japan Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation in 2008.” Highlighted was the institutionalization of various dialogue mechanisms including “Foreign and Defense Ministerial Dialogue (2+2), in addition to existing mechanisms, including the Annual Defense Ministerial Dialogue, Defense Policy Dialogue, the National Security Advisers’ Dialogue, and Staff-level Dialogues of each service.” They also welcomed “commencement of negotiations on the Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Agreement (ACSA), which will enhance the strategic depth of bilateral security and defence cooperation.”

Maritime cooperation received special mention with both the Indian and Japanese leaders acknowledging “the significant progress in maritime security cooperation, as seen in the high frequency of bilateral naval exercises and deepening level of the Malabar exercises, as well as long standing dialogues and training between the Coast Guards. Recognizing that enhanced exchanges in expanding maritime domain awareness (MDA) in the Indo-Pacific region contributes to regional peace and stability, they welcomed the signing of the Implementing Arrangement for deeper cooperation between the Indian Navy and the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF).”

Given PM Modi’s two visits to Singapore during the year, defense cooperation in the relationship received some attention. During one of the visits, an “Implementation Agreement between Indian Navy and Republic of Singapore Navy concerning Mutual Coordination, Logistics and Services Support for Naval Ships’, Submarines and Naval Aircraft (including Ship borne Aviation Assets) Visits” was signed. The two countries also agreed to establish maritime exercises with like-minded regional/ASEAN partners. Both initiatives represent an important uptick and enhancement of India-Singapore defense cooperation, concentrated in the maritime space.

Even in India’s relations with Myanmar, “bilateral cooperation…with an emphasis on maritime security…including coordinated patrolling initiatives along their land and maritime boundaries” was highlighted in the joint statement.

India’s trade and investment relations with East Asia

During 2018, Indian officials took considerable effort to provide upbeat assessments of India’s trade and investment relations with East Asia. For example, PM Modi, in his Shangri-La speech, stated that “We have more trade agreements in this part of the world than in any other. We have Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreements with Singapore, Japan and South Korea. We have Free Trade Agreements with ASEAN and Thailand. And, we are now actively participating in concluding the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement.” Specifically regarding India’s position on RCEP, Modi stated “We will also support rule-based, open, balanced and stable trade environment in the Indo-Pacific Region, which lifts up all nations on the tide of trade and investment. That is what we expect from Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. RCEP must be comprehensive, as the name suggests, and the principles declared. It must have a balance among trade, investment and services.” India’s officials provided more details on India’s thinking and negotiating posture on RCEP in background briefings. These principles do not align completely with the Trump administration’s focus on “free, fair and reciprocal trade.”

In specific bilateral relationships, too, India sought to project a positive assessment of commercial relations. During her January 2018 speech in Jakarta at the fifth Roundtable of the ASEAN-India Network of Think Tanks, EAM Swaraj gave this summary of India-ASEAN economic relations. “A deeper economic integration with the dynamic ASEAN region, is an important aspect of our Act East Policy. ASEAN is India’s 4th largest trading partner, accounting for 10.2% of India’s total trade. India is ASEAN’s 7th largest trading partner. Trade is back on track and registered an 8% increase in 2016-17, as compared to the previous year. Investment flows have also remained robust. It is our continuous attempt to promote dialogue among ASEAN and Indian business and trade associations, to further enhance bilateral trade and investment. The establishment of a Project Development Fund will encourage Indian companies to develop manufacturing hubs in CLMV countries. Our offer of a US$1 billion Line of Credit is another important initiative to enhance physical and digital connectivity.” Later in the year, PM Modi provided even better numbers saying, “…India and ASEAN enjoy close trade and economic relations. Trade between India and ASEAN stood at USD 81.33 billion in 2017-18 and constitutes 10.58% of India’s total trade. Exports to ASEAN countries constitute 11.28% of our total exports.”

India-China economic relations saw no major developments during 2018. During PM Modi and President Xi’s bilateral meeting in June in Qingdao, Xi reportedly suggested to Modi that they set a goal of $100 billion for bilateral trade by 2020. And reportedly “China is looking at [emphasis added] enhancing agriculture exports from India including non-basmati rice and sugar.” There was also some hope for more Indian pharmaceutical products being sold in China, but without any specific commitments. India continues to run a huge trade deficit with China.

Small steps regarding trade, investment, and commercial relations were taken in India’s other bilateral relationships in East Asia. India and Singapore announced the conclusion of a second review of CECA. India and Korea agreed to try reach $50 billion in trade by 2030, but noted that to facilitate achievement of such a goal early conclusion of ongoing negotiations to upgrade their bilateral Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) and implementation of trade facilitation measures would be needed. India also expressed interest in Korean investment in infrastructure modernization. During the state visit of ROK’s president to India in July, a Joint Statement on Early Harvest Package of the Upgraded Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) was issued to “facilitate ongoing negotiations on upgrading the India-ROK CEPA by identifying key areas for trade liberalization (including Shrimp, Molluscs and Processed Fish).” India and Vietnam established a trade target of $15 billion by 2020. In India-Indonesia relations the main issue was the “…high trade deficit that India has with Indonesia…” and New Delhi’s view that “…the best way to address this issue is not to restrict trade but to increase it. We agreed to work together for a balanced and sustainable trade by providing greater market access, both in goods and services.”

India and East Asia multilateralism

Beyond India’s expanded and enhanced bilateral relationships with East Asia, in his speech at the Shangri-La Dialogue PM Modi paid considerable attention to India’s multilateral efforts in the region. Modi emphasized his country’s adherence to ASEAN centrality and ASEAN-led regional organizations, saying he saw “…ASEAN as an example and inspiration” and ASEAN unity [as] essential for a stable future for this region. The East Asia Summit and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership – two important initiatives of ASEAN – embrace this geography.” Modi went on to report that India is an active participant “in ASEAN-led institutions like East Asia Summit, A.D.M.M. Plus and A.R.F.” but also of non-ASEAN-led groupings such as “BIMSTEC and Mekong-Ganga Economic Corridor – a bridge between South and Southeast Asia.” Finally, he noted that India had its own efforts at multilateralism through which it sought to “promote collective security [such as] forums like Indian Ocean Naval Symposium…[and] We are advancing a comprehensive agenda of regional co-operation through Indian Ocean Rim Association.” He also noted that he had initiated the Forum for India-Pacific Islands Cooperation to “bridge the distance of geography through shared interests and action.”

It is worth noting the multilateral efforts and groupings that PM Modi did not refer to in his Shangri-La Dialogue address. He did not refer to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), which India in 2018 attended for the first time as a full member rather than as an observer. Indeed, Modi made a visit to Qingdao, China in June just for the SCO meeting. EAM Swaraj, earlier in April, attended the SCO Council of Foreign Ministers meeting in Beijing. Nor did Modi specifically mention the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in his Shangri-La dialogue address. But he unmistakably alluded to it saying “There are many connectivity initiatives in the region. If these have to succeed, we must not only build infrastructure, we must also build bridges of trust. And for that, these initiatives must be based on respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, consultation, good governance, transparency, viability and sustainability. They must empower nations, not place them under impossible debt burden. They must promote trade, not strategic competition. On these principles, we are prepared to work with everyone.” India has taken a consistent position, at odds with nearly every country in East Asia, against BRI because BRI does not meet these criteria and because BRI makes commitments to projects in territory disputed between India-Pakistan and India-China. However, India continues to pursue a range of engagements with overlapping multilateral institutions including the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the New Development Bank and the so-called BRICS grouping of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. This hodge-podge of multilateralism reflects India’s complex global and functional interests and its utilization (and rejection) of multilateralism consistent with its perceived national interests.

Conclusion

Last year, this series asked “How receptive will India be to this convergence [between the Trump Administration’s FOIP and the Obama administration’s US-India Joint Vision for the Asia-Pacific and Indian Ocean Region].” India’s East Asia diplomatic, defense, trade and investment, and multilateral relations provide a reasonably comprehensive answer. First, India continues to pursue its relations with the region on its own terms, pace, and priorities. Second, India has clearly identified its own FOIP with overlapping characteristics with those of the US but not in complete alignment with it. Third, India seeks to frame its relations with East Asia (and the US) not in a “great power competition” framework, but in a more multipolar and autonomous vision. And finally, India seeks to engage a range of instruments and tools to fashion an East Asia engagement that serves first and foremost India’s national interests. Hence, its relations with the US will seek to benefit from overlapping interests with Washington, but not to be compliant or subservient to Washington in the East Asia region.

Jan. 4-8, 2018: India’s External Affairs Minister (EAM) Sushma Swaraj visits Thailand, Indonesia, and Singapore. In Indonesia, Swaraj co-chairs the fifth India-Indonesia Joint Commission meeting and greets new ASEAN Secretary General Lim Jock Hoi.

Jan. 24-27, 2018: Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen makes a state visit to India during which four agreements of cooperation ranging from culture to water resource development and criminal matters and human trafficking were signed.

Jan. 25-26, 2018: Leaders of the 10 ASEAN countries visit New Delhi for the ASEAN-India Commemorative Summit on the occasion of India’s 69th Republic Day of India.

March 2-4, 2018: Vietnam’s President Tran Dai Quang makes a state visit to India during which MoUs are signed to enhance trade and economic relations, technical agriculture cooperation, and cooperation on peaceful uses of atomic energy.

March 28-30, 2018: EAM Swaraj visits Tokyo to co-chair the ninth India-Japan Strategic Dialogue. In her remarks to the press, Swaraj refers to many aspects of India-Japan relations but does not mention defense or military ties.

April 22, 2018: EAM Swaraj visits Beijing to meet State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi and to attend the Shanghai Cooperation Organization’s (SCO) Council of Foreign Ministers.

April 25-26, 2018: EAM Swaraj visits Mongolia, the first by an Indian EAM in 42 years, to co-chair the sixth round of India-Mongolia Joint Consultative Committee (IMJCC) meeting.

April 26-28, 2018: Prime Minister Narendra Modi travels to China for the so-called “Wuhan Informal Summit.”

May 10-11, 2018: EAM Swaraj travels to Myanmar to discuss “boundary and border related issues, peace & security matters, developments in the Rakhine State, including return of displaced persons, India’s development assistance to Myanmar, ongoing projects, and other issues of mutual interest.”

May 29-31, 2018: PM Modi visits Indonesia, his first since becoming prime minister in 2014.

May 31, 2018: Pm Modi makes a brief visit to Kuala Lumpur to meet Malaysia’s newly-elected PM Mahathir Mohammad.

May 31-June 2, 2018: PM Modi makes his second official visit to Singapore including delivering the keynote speech at the 17th Shangri-La Dialogue.

June 9-10, 2018: PM Modi visits Qingdao, China to attend the SCO Summit. He also meets separately with President Xi.

June 12-15, 2018: India’s Defense Minister Nirmala Sitharaman visits Vietnam.

July 8-11, 2018: South Korean President Moon Jae-in makes a state visit to India.

Aug. 27-28, 2018: EAM Swaraj visits Vietnam to co-chair the 16th Joint Commission meeting and inaugurate the third Indian Ocean Conference.

Aug. 29-30, 2018: EAM Swaraj makes her first official visit to Cambodia.

Sept. 6, 2018: US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Secretary of Defense James Mattis and Minister of External Affairs Swaraj and Minister of Defense Nirmala Sitharaman meet in New Delhi to conduct the first US-India 2+2 Dialogue.

Oct. 5, 2018: President Putin and Prime Minister Narendra Modi meet in New Delhi for annual India-Russia summit.

Oct. 27-29, 2018: PM Modi travels to Japan and meets PM Abe Shinzo.

Nov. 14-15, 2018: PM Modi travels to Singapore for the second RCEP Summit, 16th ASEAN-India Breakfast Summit and the 13th ASEAN Summit.

Nov. 19-21, 2018: India’s President Ram Nath Kovind visits Vietnam.

Nov. 21-24, 2018: President Kovind visits Australia, the first-ever visit by an Indian president.

Nov. 22-23, 2018: EAM Swaraj co-chairs the ninth India-Laos Joint Commission Meeting on Bilateral Cooperation in Vientiane.

Dec. 10-14, 2018: President Kovind makes a state visit to Myanmar during which the two countries issue a joint statement.

Dec. 18-19, 2018: South Korea’s Foreign Minister Kang Kyung-wha visits New Delhi for the ninth meeting of the India-ROK Joint Commission.

Dec. 21-24, 2018: China’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Wang Yi travels to India for the third High-Level Media Forum.