Articles

2023 marks the 50th Year of ASEAN-Japan Friendship and Cooperation, and there are expectations that their relationship will be upgraded to a “comprehensive strategic partnership.” Given the good diplomatic, security, and economic relations between Japan and Southeast Asian states, ties are likely to be strengthened. However, Japan is now taking a more competitive strategy toward China, as indicated in the three security documents issued in December 2022, while Southeast Asian states generally continued the same strategic posture by which they have good relations with all great powers in the Indo-Pacific region. Also, while Japan issued the “New Plan for the Free and Open Indo-Pacific” that emphasizes the “Global South,” it remained silent about ASEAN centrality and unity in the Indo-Pacific, and it was unclear what roles Japan expects ASEAN to play. Although both Japan and Southeast Asian states need to adjust their roles in the Indo-Pacific region, it remains to be seen whether the 50th anniversary becomes an opportunity for clarification.

Golden Anniversary

The year 2023 marks the 50th Year of ASEAN-Japan Friendship and Cooperation. In 1973, Japan and ASEAN held a dialogue to resolve trade frictions regarding Japan’s export of synthetic rubber, which would likely have marginalized the value of Southeast Asia’s natural rubber. The “ASEAN-Japan forum on synthetic rubber” eventually mitigated bilateral tensions and elevated them to “dialogue partner” status in 1977. This anniversary is particularly important, considering that it’s an opportunity to strengthen Japan-ASEAN ties as US-China strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific region intensifies.

Figure 1 Japanese Foreign Minister Hayashi meets the recently-appointed Secretary-General of ASEAN, Dr. Kao Kim Hourn. Photo: Ministry of Foreign Affairs Japan

The prospect is positive. Japan has consistently supported ASEAN as a regional institution in the Indo-Pacific since ASEAN issued the “ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific” (AOIP) in 2019. In past official statements of the Quad, including the recent summit in Tokyo in May 2022, Japan always showed strong support for ASEAN unity and centrality, and Japan started to emphasize the importance of synthesizing the “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” (FOIP) and AOIP from 2020–2021. Japan and ASEAN officially issued the ASEAN-Japan Joint Statement on AOIP in 2020, and Japan focused on implementation of FOIP and AOIP, with four priority areas—maritime cooperation, connectivity, UN sustainable development goals 2030, and economic and other possible areas of cooperation—rather than pushing its own liberal political values such as democracy and human rights on Southeast Asian countries.

The Japan-ASEAN Vision Statement is expected to be issued in December 2023 as has become tradition following the 30th anniversary in 2003 and the 40th in 2013. Their relationship would also likely be upgraded to a “comprehensive strategic partnership,” a status that only three major dialogue partners—China, Australia, the United States—have attained. To further strengthen relations, Japanese nongovernmental committees were organized by Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) as well as jointly by METI and JETRO (Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry and Japan External Trade Organization) while the inter-ministerial committee also started discussion in February 2023. Additionally, a Japanese private sector group, Keizai Doyukai (Japan Association of Corporate Executives), submitted the report of the 48th ASEAN-Japan Business Meeting, emphasizing that the relationship between Japan and ASEAN is no longer that of developed-developing countries given ASEAN members’ rising economic status and Japan’s relative economic decline. The political and economic momentum is therefore strong.

Both Japan and Southeast Asian states recognize the importance of redefining and enhancing their ties. This is particularly so because intensification of US-China strategic competition could narrow their strategic choices by increasing the risk of entrapment in great power competition. In this context, Japanese Foreign Minister Hayashi Yoshimasa expressed Japan’s support for mainstreaming of the AOIP in February 2023 as ASEAN pushes implementation of priority areas in the AOIP by adopting the “ASEAN Leaders’ Declaration on mainstreaming Four Priority Areas of the AOIP on the Indo-Pacific Within ASEAN-Led Mechanisms” in November 2022.

Despite these positive developments, there are uncertainties in the Indo-Pacific region that neither Japan nor Southeast Asian states can dispel, which will require strategic adjustment from both sides.

Southeast Asia in Japan’s New Security Strategy and New Plan for FOIP

Arguably, the most significant change in Japanese policy is the Kishida administration’s issuance of three security documents in December 2022, namely the National Security Strategy (NSS), National Defense Strategy (NDS), and Defense Buildup Program. These documents present important changes in Japanese defense policy that clarify its intention to drastically increase defense capabilities, including the acquisition of counterstrike capabilities. In terms of Japan-Southeast Asia relations, which are mainly focused on the diplomatic aspect of Japan’s security policy, the NSS is the document to examine as it explains Japan’s strategic perspective. Nevertheless, there is not much description of Southeast Asia and ASEAN in the NSS. In fact, the document is not quite sufficient in explaining its strategic vision, and instead, the NSS “Indo-Pacific” is narrowed to Northeast Asia, particularly China, Russia, and North Korea.

Given the steady increase in Japan’s threat perceptions toward these neighboring states, this strategic priority is understandable. Nevertheless, compared with the 2013 NSS that discussed diplomatic posture toward regional states and institutions, including Southeast Asian states and ASEAN, the 2022 NSS only described ASEAN as one of many frameworks, with which Japan aims to widen its networks and enhance deterrence in general. The NDS puts more emphasis on Japan’s effort to support ASEAN-led institutions as well as ASEAN’s institutional principles, ASEAN centrality and unity, while noting that the promotion of capacity-building and transfer of defense equipment is necessary to empower Southeast Asian states’ deterrence capabilities. In this sense, it becomes unclear what Japan expects of Southeast Asia in its overall security strategy as well as the FOIP vision.

Prime Minister Kishida Fumio made a speech, “The Future of the Indo-Pacific: Japan’s New Plan for a ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’” in New Delhi, on March 20, 2023. This essentially built on his earlier speech in the United States in January 2023 that highlighted the necessity of engaging with the “Global South.” The Delhi speech also complemented the three security documents, clarifying Japan’s strategic posture in the Indo-Pacific region. Japan expressed its recognition of the different strategic perspectives existing in the “Global South.” While many in the United States and its allies/partners believe that international rules and norms based on liberal values should be defended to maintain the existing international law, Global South states see those values differently because of differing historical and cultural backgrounds. This resonates with Southeast Asian states’ long-held skepticism about “political values” arguments, such as the dichotomic classification between democracy and autocracy, that have been pushed by the United States. Therefore, Japan’s new statements would likely be well received in Southeast Asia.

Yet even with the new plan for the FOIP, the Kishida administration has yet to be sufficiently clear in articulating Japan’s expectations of Southeast Asia. Admittedly, Japan has been consistent in supporting ASEAN and ASEAN-led institutions. However, while Kishida’s January speech in the United States describes ASEAN as “the closest and most crucial partner” in the Global South, the New Plan for FOIP does not indicate ASEAN as such. Instead, Kishida mentioned Southeast Asia as one of the three most important regions (the other two are South Asia and the Pacific Islands) in terms of “multi-layered connectivity” that consists of soft and hard connectivity. He was also silent about ASEAN centrality and unity in the Indo-Pacific region. In other words, although Kishida has seemingly situated ASEAN as the indispensable partner to manage Japan’s Global South relations, he did not explain how ASEAN would be helpful for Japan.

Although Southeast Asian states did not react to these documents and plans immediately, if these issues are left unclear, they may believe that Japan’s support for ASEAN centrality and unity in the Indo-Pacific region are inconsistent with its national strategy and only diplomatic rhetoric. Whether Japan will clarify the strategic role of ASEAN and Southeast Asian countries in the Indo-Pacific at the 50th anniversary of ASEAN-Japan relations is an important issue to monitor.

Diplomatic Relations: Ukraine War, Myanmar, and ASEAN Unity

Apart from these strategic perspectives, Japanese and Southeast Asian diplomatic relations remained positive. This is indicated by the fact that Japan was again considered the most trusted major power according to the annual survey conducted by the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, The State of Southeast Asia 2023. This positive relationship has been cultivated by Japan’s ongoing contributions to Southeast Asia’s socio-economic development, but at the same time, Japan under the Abe administration played an important strategic role as an alternative as US-China strategic competition intensified. This explains the presence of Southeast Asian leaders, namely Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen, Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, and Vietnamese President Nguyen Xuan Phuc, at the state funeral of Abe Shinzo in September 2022 along with other Southeast Asian representatives, such as Indonesian Vice President Ma’ruf Amin, Thailand’s Deputy Prime Minister Don Pramudwinai, Philippine Vice President Sara Duterte, and Malaysia’s Senior Minister Mohamed Azmin Ali. This illustrates that Japan-Southeast Asia friendship exists in its own right.

Japan-Southeast Asian states’ bilateral diplomatic relations also saw progress. Japan and Cambodia agreed on a Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) regular visit to the Ream base, which the United States has been suspicious about China’s potential use. Also, in November 2022, they also decided to upgrade their relationship to the “comprehensive strategic partnership” since 2023 is the 70th anniversary of Japan-Cambodia relations. Also, Malaysia and Japan decided to upgrade their ties to a “comprehensive strategic partnership,” expanding their areas of cooperation. Additionally, Thailand and Japan upgraded their relationship to a “comprehensive strategic partnership” to focus on three areas of cooperation, “(1) human resource development, regulatory reform, innovation, (2) Bio-Circular-Green (BCG) Economy and (3) infrastructure.”

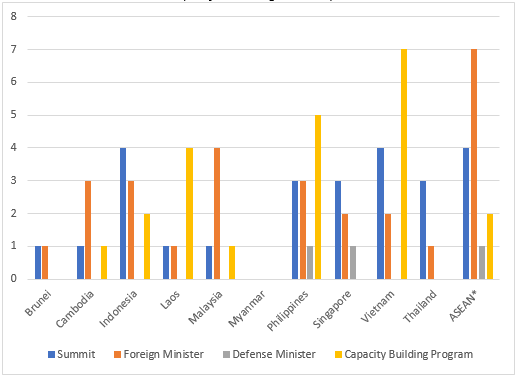

Overall, as Figure 1 shows, Prime Minister Kishida and Foreign Minister Hayashi have been actively meeting with counterparts in ASEAN member states except for Myanmar. At the same time, given the replacement of Defense Minister Kishi Nobuo by Hamada Yasukazu in August 2022 and given Japan’s preparation of new security documents, there was less high-level defense diplomacy at the ministerial level. In November 2022, Japan’s defense minister missed the ADMM-Plus for the first time, and Parliamentary Vice-Minister of Defense Onoda Kimi participated instead.

Figure 2 Diplomatic Interactions between Japan and Southeast Asian Countries (May 2022-April 2023) including ASEAN-related formal and informal meetings, such as the ARF and EAS. Source: Data from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, compiled by the Author

That said, strategic concerns in the period of power-shift did not cease between Japan and Southeast Asian states, affecting ASEAN centrality and unity. First, there was strategic divergence between Japan and Southeast Asian states over the Ukraine War. Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Japan has consistently called for the condemnation of Russia’s unprovoked attacks that are a clear violation of international law, state sovereignty, and the territorial integrity of Ukraine; imposing strong economic sanctions on Russia; and coordinating Ukraine policy with G7 member states. Japan’s firm stance derives from a simple logic: the international community should not reward an aggressor because doing nothing affects the international perception that a fait accompli invasion can be implemented, and that international rules and norms are not worth protecting. As a result, Japan’s move aims to punish Russia.

ASEAN member states’ postures diverge. While Singapore is essentially aligned with Japan’s position, as well as that of the United States and its partners, other member states are more cautious about naming-and-shaming tactics and the imposition of economic sanctions. Vietnam, which has strong political and military relations with Russia, consistently refrained from condemning Russia’s actions. Cambodia, Indonesia, and Thailand, the 2022 chairs of G20, APEC, and ASEAN, respectively, issued the joint statement in May 2022, inferring that they did not exclude any members from those international forums. Japan regularly reports its firm position and rationale on the Ukraine War through the summit and ministerial meetings, but it has not yielded any substantial changes in Southeast Asian stances.

Meanwhile, the Myanmar situation has been stalemated and affects ASEAN unity. Although Japan supported ASEAN’s “Five-Point Consensus” agreed in April 2021, there has yet to be implementation. ASEAN has refused to invite the Tatmadaw to high-level meetings as the official representative of Myanmar. Japan also stopped diplomatic interaction with Myanmar, including the Mekong-Japan Summit Meeting in the past three years. Instead, Japan has issued a series of foreign minister’s statements for returning to a democratic political system, including this one in February 2023, two years after the coup, while stopping its ODA except for socio-economic assistance for those affected by the coup with cooperation from UNICEF. It has had no affect: the Tatmadaw accelerated democratic backsliding, as illustrated by its execution of pro-democracy activists in July 2022 and the dissolution of the National League of Democracy (NLD) in March 2023.

The Tatmadaw strengthened ties with Russia and China, which do not condemn the coup and continue diplomatic and economic relations with Myanmar under the noninterference principle rather than cooperating with ASEAN or other external actors, such as Japan, to pursue the 5-Point Consensus. This Myanmar situation not only weakens ASEAN’s internal unity but also provides Russia and China a tool to drive a wedge between ASEAN member states. ASEAN and Japan thus face a strategic dilemma. For ASEAN, engaging the Tatmadaw essentially justifies its political legitimacy and allows it to be criticized by advanced democracies, such as the United States and the EU. Yet, if it does not do so, the stalemate will likely continue. For Japan, economic sanctions and political isolation of the Tatmadaw is consistent with its values. However, this would provide the junta still more incentives and justification to align with Russia and China. Since a change in the current policy is costly for both, the diplomatic stalemate is likely to persist.

Security Relations: Defense Diplomacy and Japan-Philippines Relations

Japan’s security engagement toward Southeast Asia remained strong. Japan continuously shows its presence by dispatching defense assets to the region. Notably, the JMSDF conducted its annual naval deployment, the “Indo-Pacific Deployment 2022” (IPD22), sending vessels such as the DHH-183 Izumo, DD-110 Takanami, and DD-104 Kirishima to the Indo-Pacific region, including the Philippines, Vietnam, and the Pacific Islands. Also, as the defense diplomacy hiatus caused by COVID-19 is being eased, Japan conducted the 5th Japan-ASEAN Invitation Program on Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief and the 4th Japan-ASEAN Ship Rider Cooperation Program under the “Vientiane Vision 2.0” in February and March 2023, respectively. The former was the first in two years (2021), and the latter was the first in four years (2019). From February to March 2023, Japan also participated in US-Thai-led multilateral joint military exercise, Cobra Gold 23, with Indonesia, Malaysia, South Korea, Singapore, Australia, China, and India.

Bilateral defense dialogue cooperation also made progress. In addition to the bilateral capacity-building program with Indonesia, Cambodia, and Malaysia, Japan engaged with the Philippines, Vietnam, and Laos most frequently in this period. The Philippines not only received various capacity-building programs, such as the Humanitarian Assistance/Disaster Relief (HA/DR) and the three-year project of Vessel Maintenance Cooperation, but also conducted the first US-Japan-Philippines trilateral defense policy dialogue to exchange views on common security challenges, including the maintenance of maritime security stability and the rules-based order. Additionally, Japan and the Philippines concluded terms of reference for HA/DR in February 2023 to simplify the process of military cooperation, such as the SDF’s visit to the Philippines. Vietnam and Laos received a high number of capacity-building programs, such as cyber security, underwater UXO clearance, search and rescue, military medicine, and engineering.

Against this backdrop, Japan’s creation of “Official Security Assistance” (OSA) in April 2023 will play an important role in shaping Southeast Asia’s strategic environment. OSA was established based on the 2022 NSS, which enables Japan to provide “equipment and supplies” and “assistance for infrastructure development” such as satellite communication systems and radio communication systems, “to the countries with a view to strengthening their capacities and improving their deterrence capabilities.” While ODA’s original focus remains on socio-economic development, OSA is a grant for defense-related capacity-building to developing states, which would make defense capacity-building easier administratively and operationally. The target states in FY2023 will be two Southeast Asian states, the Philippines and Malaysia, in addition to Bangladesh and Fiji.

Japan and Southeast Asia maintained regular interactions and steadily developed bilateral defense cooperation with each Southeast Asian state. In 2022-2023, Japan conducted institutionalized defense diplomacy with the Philippines via the 9th Military-Military (MM) Dialogue, Malaysia through the 7th MM Dialogue in October 2022, Cambodia through the 7th Politico-Military (PM) Dialogue in February 2023, and Singapore through the 18th MM Dialogue in March 2023. Brunei and Japan agreed to newly establish the “Defense Policy Dialogue” at the vice-minister of defense level.

Among them, Japan’s specific emphasis was on defense relations with the Philippines. Given Japan’s increasing security concerns vis-à-vis the Taiwan Strait and the Philippines’ renewed balanced diplomacy under the Marcos administration, both strengthened security ties with each other and with the United States. While nontraditional security issues, particularly HA/DR, remained the primary security focus, Japan’s OAS to the Philippines is being framed as a traditional security concern. This strategic posture, however, is not completely shared with the Philippines, which seeks balanced relationship with great powers to ensure its own national interests, and thus, the degree to which the Philippines would “tilt” among the great powers depends on the development of the strategic environment.

Socio-Economic Relations: IPEF and Asia Zero Emission Community

Economic relations between Japan and Southeast Asia remained stable in the post-COVID-19 period. While Japan’s direct investment toward ASEAN in Japanese fiscal year 2022 was 2.6539 trillion yen ($20 billion), dropping approximately 10% from a year earlier, its net share of Japan’s total outward direct investment, 11.7%, exceeded China’s (5.2%). ASEAN-Japan trade relations also gradually recovered from the negative impact of COVID in 2020, with a 26.6% increase in Japan’s exports to ASEAN and 16.9% in Japan’s imports from ASEAN between 2020 to 2021. Given the rise of US-China technological decoupling and geoeconomic competition, Japan and Southeast Asian states look for means to diversify economic risks, which becomes an additional incentive for them to strengthen ties with each other.

Also in this period, Japan and Southeast Asian states attempted to support the establishment of “Asia Zero Emission Community” (AZEC). As the joint initiative of Japan and Indonesia in November 2022, AZEC aims to promote regional decarbonization to achieve the objectives of the Paris Agreement and facilitate energy transition while considering each member state’s socio-economic situation. So far, the community consists of Australia and ASEAN-minus-Myanmar, and it promotes comprehensive cooperation among member states. The first ministerial meeting was held in March 2023. As this initiative was created on the sidelines of the G20, Japan as 2023 chair of G7 would likely introduce the concept to the G7 and G20 with cooperation from India, 2023 chair of the G20 for the realization of carbon-neutral societies.

Another cooperative framework in the Indo-Pacific that Japan and Southeast Asian states paid attention to was the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF). The United States looked for ways to become more involved in economic cooperation in the Indo-Pacific region. Since the US has already withdrawn from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and is highly unlikely to commit to any free trade agreements because of domestic opposition, the Biden administration took the initiative to establish IPEF. However, Washington initially framed this grouping in the US-China strategic competition, and the administration aimed to include only “like-minded” states without inviting all the ASEAN member states such as Thailand. As Japan considered ASEAN members’ involvement to be vital and suggested that the US invite them, Washington decided to include ASEAN members except for Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar.

IPEF members from Southeast Asia generally welcome this US initiative since it shows its involvement in regional economic affairs; however, several ASEAN members remained cautious. For example, Cambodia’s Hun Sen indicated that any economic cooperative frameworks needed to support ASEAN Centrality in May 2022. Negotiations over the four pillars—1) trade, 2) supply chains, 3) clean energy, decarbonization, and infrastructure, and 4) tax and anti-corruption—continue, and because of US unwillingness to reduce tariffs, the outcome is uncertain. Japan and Southeast Asian members also want to assure non-IPEF ASEAN members that the IPEF would not compete with ASEAN in the Indo-Pacific.

Southeast Asian states prefer cooperation to geopolitical and geoeconomic competition that would divide not only the Indo-Pacific but also Southeast Asia. Given deepened economic relations with China and traditionally strong trade ties with the United States, it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, for Southeast Asian states to consider economic decoupling with China or to weaken economic links with the United States. As such, Japan’s concept of “economic security” does not resonate with the interests of Southeast Asia, although bilateral and multilateral information-sharing and discussion remain imperative. Rather than accepting confrontational postures, Southeast Asia is more likely to accept future-oriented cooperative economic measures, such as the Japan-Indonesia joint initiative for AZEC.

Looking Ahead

As a great power politics evolve rapidly and Japan’s threat perceptions toward China converge with those of the United States, Japan has inclined toward a more competitive national security strategy. This was well-illustrated by Japan’s support for US initiatives in countering China, such as US-Dutch-Japan Trilateral Semiconductor Export Controls, as well as three security documents issued in 2022. Southeast Asian states maintained their traditional strategic posture, hedging against the risk of great power politics. To that end, ASEAN under the Indonesian chair in 2023 has doubled down its strategy to maintain good relations with all major powers in the Indo-Pacific and took an initiative to mainstream the four priority areas of the AOIP. Moreover, ASEAN gradually moves to clarify what it means by ASEAN Centrality in the Indo-Pacific—maintaining ASEAN Centrality within ASEAN-led mechanisms and reach out to other regional institutions, such as the Pacific Islands Forum—so that the association can shape the regional order.

Figure 3 Samdech Akka Moha Sena Padei Techo Hun Sen, Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Cambodia and Chair of ASEAN 2022, co-chaired with Kishida Fumio, Prime Minister of Japan, the 25th ASEAN-Japan Summit in Phnom Penh on the afternoon on November 12, 2022

The good news is that while focusing on geopolitical and geoeconomic competition with China, Japan considers the “Global South” countries important in shaping a new international order. The Kishida administration highlights “rulemaking through dialogues” with the international community under the FOIP that respects diversity, inclusiveness, and openness. Japan is willing to actively engage the Global South. The bad news is that Japan has yet to clarify its priority among the Global South, which consists of diverse regions and strategic environments. The Kishida administration always emphasizes the importance of ASEAN and Southeast Asia, but it does not discuss their relative importance for Japan.

In a rapidly changing strategic environment in the Indo-Pacific region and beyond, the future of Japan-Southeast Asia relations has become increasingly complex. Now that Japan has conceptually organized its security policy, new strategic adjustments will be necessary to define Japan-Southeast Asia relations. But it remains to be seen how they situate each other’s strategic roles on the 50th anniversary of Japan-ASEAN friendship and cooperation.

May 2, 2022: Japan-Thailand Summit between Kishida and Prime Minister/Minister of Defense Prayut Chan-o-cha. Japan-Thailand Agreement on the Transfer of Defense Equipment and Technology is also concluded.

May 16-20, 2022: Defense capacity-building program on Underwater UXO Clearance is conducted between Japan and Vietnam.

May 25, 2022: Japan-Singapore Foreign Ministers Meeting held between FM Hayashi and Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan.

May 25, 2022: Japan-Malaysia Foreign Minister Meeting held between FM Hayashi and Foreign Minister Saifuddin bin Abdullah.

May 26, 2022: Japan-Singapore Summit takes place between Kishida and Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong.

May 26, 2022: Japan-Thailand Summit takes place between Kishida and Prime Minister/Minister of Defense Prayut.

May 27, 2022: Japan-Malaysia Summit takes place between Kishida and Prime Minister Ismail Sabri bin Yaakob.

June 2-9, 2022: Japan-Philippines Vessel Maintenance Cooperation Project is conducted as part of Japan-Philippines-United States trilateral cooperation.

June 10-17, 2022: Japan-Philippines capacity-building program on aviation medicine is conducted.

June 10, 2022: Prime Minister Kishida makes keynote speech at Shangri-La Dialogue.

June 11, 2022: Japan-Singapore Summit takes place between Kishida and Lee and a meeting with President Halimah Yacob. Japan-Singapore Defense Ministers Meeting between Minister Kishi and Minister Ng Eng Hen.

June 22, 2022: ASEAN-Japan Defense Ministers’ Informal Meeting held with Defense Minister Kishi and ASEAN Defense Ministers.

June 30, 2022: Foreign Minister Hayashi attends the inauguration of Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos.

July 8, 2022: Japan-Indonesia Foreign Ministers Meeting held between Hayashi and Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi.

July 12, 2022: Japan-Philippines Foreign Ministers’ Telephone Talk occurs between Hayashi and Foreign Secretary Enrique Manalo.

July 25, 2022: Foreign Minister Hayashi issues statement, “Regarding Executions of Myanmar Citizens including Pro-democracy Activists.”

July 26, 2022: Hayashi releases “Joint Statement on Execution of Pro-Democracy and Opposition Leaders in Myanmar” with Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Norway, Republic of Korea, the UK, and the US.

July 27, 2022: Japan-Indonesia Summit takes place between Kishida and Jokowi.

July 28, 2022: Foreign Minister Hayashi issues “G7 foreign Ministers’ Statement on the executions by the military junta in Myanmar.”

July 29, 2022: Japan and Laos sign Memorandum of Cooperation (MOC) on “Specified Skilled Worker.”

Aug. 4, 2022: FM Hayashi participates in ASEAN-Japan Foreign Ministers Meeting and ASEAN+3 Foreign Ministers Meeting that issues the “ASEAN Plus Three Cooperation Work Plan (2023-2027).

Aug. 4, 2022: Japan-Cambodia Foreign Ministers Meeting held between Hayashi and Deputy Prime Minister/Foreign Minister Prak Sokhorn. Hayashi met Kao Kim Hourn, minister attached to the prime minister.

Aug. 4, 2022: Japan-Vietnam Foreign Ministers conversation takes place between Foreign Minister Yoshimasa Hayashi and Vietnamese Foreign Minister Bui Thanh Son.

Aug. 5, 2022: FM Hayashi participates in ASEAN Region Forum and EAS Foreign Ministers Meeting. Hayashi also met ASEAN Secretary-General Lim Jock Hoi.

Aug. 5, 2022: Japan-Brunei Foreign Ministers meeting held between Hayashi and Foreign Minister Erywan.

Aug. 6, 2022: Japan-Laos Foreign Ministers Meeting held between Hayashi and Foreign Minister Saleumxay Kommasith.

Aug. 17, 2022: Japan-Philippines Foreign Ministers’ Telephone Talk occurs between Hayashi and Manalo.

Sept. 2, 2022: Japan-Malaysia Foreign Minister Telephone Talk occurs between Hayashi and Saifuddin.

Sept. 8, 2022: 5th Japan-Philippines Vice-Ministerial Strategic Dialogue is held.

Sept. 11-15, 2022: Defense capacity-building program on Air Rescue is conducted between Japan and Vietnam.

Sept. 21, 2022: Japan-Philippines Summit-Level Working Lunch takes place between Kishida and Marcos.

Sept. 22, 2022: FM Hayashi issues statement, “Completion of the Khmer Rouge Trials.” Japan has contributed financially (30% of the international assistance) to setting up the Khmer Rouge Trial

Sept. 26, 2022: Japan-Vietnam Summit takes place between Kishida and President Nguyen Xuan Phuc.

Sept. 27, 2022: Japan-Singapore Summit takes place between Kishida and Lee.

Sept. 28, 2022: Japan-Cambodia Summit meeting takes place between Kishida and Prime Minister Hun Sen.

Oct. 8, 2022: Foreign Minister Hayashi holds meeting with Singaporean Senior Minister Tharman Shanmugarathnam. Foreign Ministers’ Level Working Lunch between Hayashi and Balakrishnan also takes place.

Oct. 9, 2022: FM Hayashi makes a visit to Malaysia, meeting with Foreign Minister Saifuddin and Senior Minister/MITI Minister Mohamed Azmin Ali.

Oct. 10-11, 2022: Defense capacity-building program on Underwater Medicine is conducted between Japan and Vietnam.

Oct. 17-20, 2022: Japan-Philippines HA/DR Cooperation project is conducted.

Oct. 26-27, 2022: Defense capacity-building program on vessel maintenance is conducted between Japan and the Philippines.

Oct. 28, 2022: Japan-Indonesia Summit Telephone Talk occurs between Kishida and Jokowi.

Nov. 4, 2022: 13th Japan-Philippines High Level Committee on Infrastructure Development and Economic Cooperation held. Japan-Philippines Summit Informal Talk between Japan and the Philippines.

Nov. 8, 2022: Japan-Indonesia foreign ministers’ telephone call between Hayashi and Marsudi takes place.

Nov. 12, 2022: Japan-Laos Summit Informal Talk between Kishida and Prime Minister Phankham Viphavanh.

Nov. 12, 2022: Kishida attends ASEAN+3 Summit and the ASEAN-Japan Summit.

Nov. 13, 2022: Kishida participates in the 2nd ASEAN Global Dialogue initiated by Cambodia. Kishida participated in EAS.

Nov. 13, 2022: Japan-Vietnam Summit takes place between Kishida and PHAM Minh Chinh.

Nov. 13, 2022: Japan-Vietnam Summit takes place between Kishida and PHAM Minh Chinh.

Nov. 14, 2022: Japan-Indonesia Summit takes place between Kishida and Jokowi. Japan and Indonesia issued a “Joint Announcement on Asia Zero Emission Community (AZEC) Concept.”

Nov. 14-17, 2022: Japan-Malaysia HA/DR Cooperation Project is conducted.

Nov. 17, 2022: Japan-Thailand Summit between Kishida and Prayut. Japan and Thailand decided to upgrade relationship to “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership.” Japan-Thailand Foreign Minister Meeting between Hayashi and Deputy Prime Minister/Foreign Minister Don Pramudwinai. “Five-Year Joint Action Plan on Japan-Thailand Strategic Economic Partnership: Towards a More Resilient and Sustainable Future” is agreed upon.

Nov. 17, 2022: Japan-Vietnam Foreign Ministers Meeting takes place between Hayashi and Foreign Minister Bui.

Nov. 23, 2022: Parliamentary Vice-Minister of Defense Onoda participates in 9th ADMM-Plus.

Dec. 5-15, 2022: Defense capacity-building program on Underwater UXO Clearance is conducted.

Dec. 6, 2022: FM Hayashi meets Minister Kao Kim Hourn, next secretary-general of ASEAN.

Dec. 12-16, 2022: Defense capacity-building program on HA/DR (search and rescue and military medicine) is conducted.

Dec. 14, 2022: Japan-Singapore Experts Level Meeting on Digital Economy Cooperation is held.

Dec. 16-20, 2022: Japan-Indonesia HA/DR Cooperation Project conducted as Japan’s defense capacity-building program.

Dec. 20-23, 2022: Defense capacity-building program on cybersecurity conducted between Japan and Vietnam.

Dec. 22, 2022: Japan-Malaysia Foreign Ministers’ Telephone call occurs between Hayashi and Foreign Minister Zambry Abdul Kadir.

Jan. 18, 2023: Planning Committee on Japan-Singapore Partnership Program for the 21st Century, JSPP21, takes place.

Jan. 23-February 2023: Defense capacity-building program on HA/DR (engineering) is conducted between Japan and Laos.

Jan. 24, 2023: Japan-Cambodia Foreign Ministers Meeting takes place between Hayashi and Sokhonn.

Feb. 1, 2023: Foreign Minister Hayashi issues the statement, “The Situation in Myanmar Two Years after the Coup d’Etat.”

Feb. 7, 2023: 7th Japan-Cambodia Politico-Military (PM) Dialogue takes place.

Feb. 9, 2023: Japan-Philippines Summit between Kishida and Marcos, issues “Japan-Philippines Joint Statement.” Terms of Reference (TOR) concerning Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) Activities of the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) in the Republic of the Philippines is signed.

Feb. 9, 2023: Japan-Vietnam Summit Video Teleconference Meeting takes place between Kishida and Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong.

Feb. 13-17, 2023: 5th Japan-ASEAN Invitation Program on Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief is conducted.

Feb. 15, 2023: First Japan-Brunei Policy Meeting at Senior Official Level is held.

Feb. 28-March 15, 2023: Japan-Philippines Vessel Maintenance Cooperation Project is conducted.

March 2-8, 2023: Defense capacity-building program on HA/DR (search and rescue and military medicine) is conducted between Japan and Laos.

March 6, 2023: Japan-Indonesia Foreign Ministers Meeting between Hayashi and Marsudi takes place.

March 6-9, 2023: Defense capacity-building program on Air Rescue is conducted between Japan and Vietnam.

March 14-17, 2023: Japan-ASEAN Ship Rider Cooperation Program is conducted.

March 27, 2023: 6th Japan-Philippines Vice Minister Level Strategic Dialogue is held.

March 29, 2023: 5th Japan-Philippines Maritime Dialogue is held.