Articles

In the first third of 2019, senior Chinese leaders devoted little attention to the South China Sea and China’s relations with Southeast Asian countries. Infrequent comments depicted slow progress in negotiations on a code of conduct in the South China Sea and steady advances with its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), offering strong economic incentives for closer regional cooperation with China. ASEAN and Southeast Asian claimants adhered to Beijing’s demands to avoid reference to the 2016 UNCLOS tribunal ruling against China’s South China Sea claims and to handle disputes through negotiations without outside interference. Routine complaints about more frequent US freedom of navigation exercises and other US and allied military operations in the South China Sea came from lower-level ministry spokespersons. Little attention was given to growing angst in Southeast Asia that intensified US-China competition compels countries to take sides, a choice undermining strategies that seek benefits from close ties with both the US and China.

ASEAN, South China Sea

Foreign Minister Wang Yi underlined Chinese confidence in recent relations with Southeast Asia in a speech reviewing 2018 international developments. Hailing successful visits to the region by President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang, Wang highlighted progress made in the China-ASEAN comprehensive strategic partnership, consultations on the code of conduct in the South China Sea, and efforts by China and ASEAN member states to maintain stability and conduct maritime cooperation in the South China Sea based on “increased mutual trust.” Briefly taking aim at “shows of force” of unnamed nonregional countries conducting “freedom of navigation” operations, Wang argued they would “by no means” upset overall stability in the South China Sea.

Unlike past years when South China Sea matters were more prominently addressed, senior Chinese leaders generally ignored such matters in the annual National People’s Congress government report and press conferences by the premier and the foreign minister. Even Premier Li’s keynote speech at the annual Boao Forum for Asia in March paid little attention to China-Southeast Asian relations or the South China Sea. China’s attention to China-Southeast Asia relations during the second Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Forum in late April likewise focused on the positive impact of the many large-scale infrastructure projects that would improve economic ties through regional connectivity.

Criticism of more frequent US freedom of navigation and other navy and B-52 bomber operations in the South China Sea by Chinese Defense and Foreign Ministry spokespersons and official media remained low-key. Also criticized was Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s rebuke in March of Beijing’s use of coercion to prevent Southeast Asian claimants from developing energy resources in the South China Sea. Other official Chinese media coverage of Southeast Asia and the South China Sea featured articles highlighting progress made in integrating China more closely with Southeast Asian economies, movement (albeit slow) toward completing the China-supported Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) regional free trade agreement involving China and ASEAN countries but not the United States, and China working alone or with others in restoring coral reefs and sustaining environmental conditions in the South China Sea. In January, Beijing announced the establishment of a maritime rescue center on Fiery Cross reef in the Spratly Islands. In March, the Communist Party secretary of the Sansha administrative region for China’s South China Sea territories, which is headquartered in Woody Island in the Paracel Islands, announced plans to build “an island city” that would convert Woody Island and nearby islets into a “national key strategic service and logistical base.”

Global Times and other Chinese outlets with greater editorial freedom than official party-state media showed some concern about intensified US rivalry with China and its impact on China-Southeast Asian relations. They noted stepped-up US military operations, the recent trend of US allies and partners Australia, Japan, Great Britain, and France challenging China’s claims with naval deployments, and their support for the 2016 UNCLOS tribunal ruling against China’s South China Sea claims. And they agreed with Southeast Asian specialists that progress in the code of conduct negotiations would be complicated, notably as Southeast Asian claimants sought support from the US and its allies to back their claims against China. The commentary said that Beijing would seek to use the code of conduct negotiations “to eliminate interference from countries outside the region.”

Regional commentary highlighted dilemmas for Southeast Asian governments seeking to avoid negative consequences from the intense US-China trade disputes and broader US rivalry with China. Singapore commentator Ja Ian Chong judged that both China and the United States are viewed with distrust by regional governments facing increased pressures from both that upset regional strategies to avoid alignment with one or the other.

Philippines: China presses territorial claim amid intensified US rivalry

President Rodrigo Duterte’s efforts to ease South China Sea tension with China, pursue advantageous economic deals under China’s BRI, and distance the Philippines from close alliance relations with the United States hit a major roadblock with China’s intimidation of Philippine efforts to construct modest infrastructure upgrades in the Philippine-occupied Thitu Island. Since January, hundreds of Chinese vessels said to be part of Beijing’s maritime militia have been involved in a standoff near Thitu Island, with the presumed intent of intimidating the Philippine occupiers and halting construction activity. According to the CSIS Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, in early March, the presence of suspected maritime militia boats spread to two smaller nearby Philippines-held features. The issue prompted thousands of Philippine citizens to protest the Chinese “invasion,” and shifted opinion against China in the lead-up to important nationwide legislative elections in May. In response, Duterte warned China to stop the pressure or he would order his soldiers to defend the territory. His chief aides were more vocal in criticizing China’s “assault.” The issue did not disrupt Foreign Secretary Teodoro Locsin’s inaugural visit to China in March, which went smoothly according to official Chinese media. The foreign secretary’s visit was in preparation for Duterte’s attendance at the BRI Forum in Beijing in April. Philippine officials hailed Duterte’s “highly successful” visit in late April, featuring numerous economic agreements and private talks with Xi Jinping on the dispute over Thitu Island.

View of the Subic Bay shipyard. Photo: AFP

The increased tensions over Chinese pressure came as Philippine leaders worried about China’s intentions and uncertainty about the US alliance. In January, a former Philippines Navy chief warned against the reported interest of Chinese companies in acquiring the Philippines largest shipyard in Subic Bay, then in bankruptcy. Subsequently, Philippines Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana advocated that rather than have the bankrupt shipyard in Subic Bay be taken over by Chinese or other foreign companies, the Philippines government should acquire the facility as a naval base.

Also in January, Lorenzana gave a speech focused on rising South China Sea disputes in which he called for a review of the Philippines defense treaty with the United States. Among other things, he sought clarification on whether the Philippines had to get involved if a shooting war broke out between the US and Chinese forces in the Philippines-claimed areas of the South China Sea. Some US specialists judged that the review suggestion was the defense minister’s way of pressing the United States to clarify the application of the defense treaty to apply to Philippines occupied outposts in the South China Sea. Visiting Manila on March 1, Secretary of State Pompeo offered the strongest US support for the Philippines on this matter. He said that “any armed attack on Philippines forces, aircraft or public vessels in the South China Sea would trigger mutual defense obligations under Article 4 of our mutual defense treaty.” That Pompeo’s remarks did not satisfy Philippines defense minister’s concern seemed evident when Lorenzana told the media on March 5 that he still sought a review of the treaty, noting his concern that the Philippines could be “automatically involved” in a “shooting war” involving US and Chinese forces in Philippines claimed waters of the South China Sea.

Chinese media rebuked Pompeo for attempting to sow discord between the Philippines and China. The Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson reacted mildly to the deployment of a US amphibious assault ship outfitted with fifth generation F-35B jet fighters as part of the annual Exercise Balikatan with the Philippines in April.

Malaysia: controversial railroad project successfully renegotiated

On April 12, the Malaysian and Chinese governments announced the renegotiation of a deal to build the China-backed East Coast Rail link. The project, with an estimated cost of about $20 billion, was criticized and canceled by the incoming government of Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamed in 2018 as too expensive and poorly negotiated by the corrupt Malaysian government of former Prime Minister Najib Razak. Media reports in January disclosed that Razak signed the rail deal and a companion deal for pipelines built by China, and made other concessions to Beijing in return for Chinese support. Chinese backing was sought to help the beleaguered Malaysian government in the face of US government and media investigations and other pressures showing the extent of the regime’s corrupt practices in plundering a multibillion-dollar government investment fund for the leaders’ private benefit.

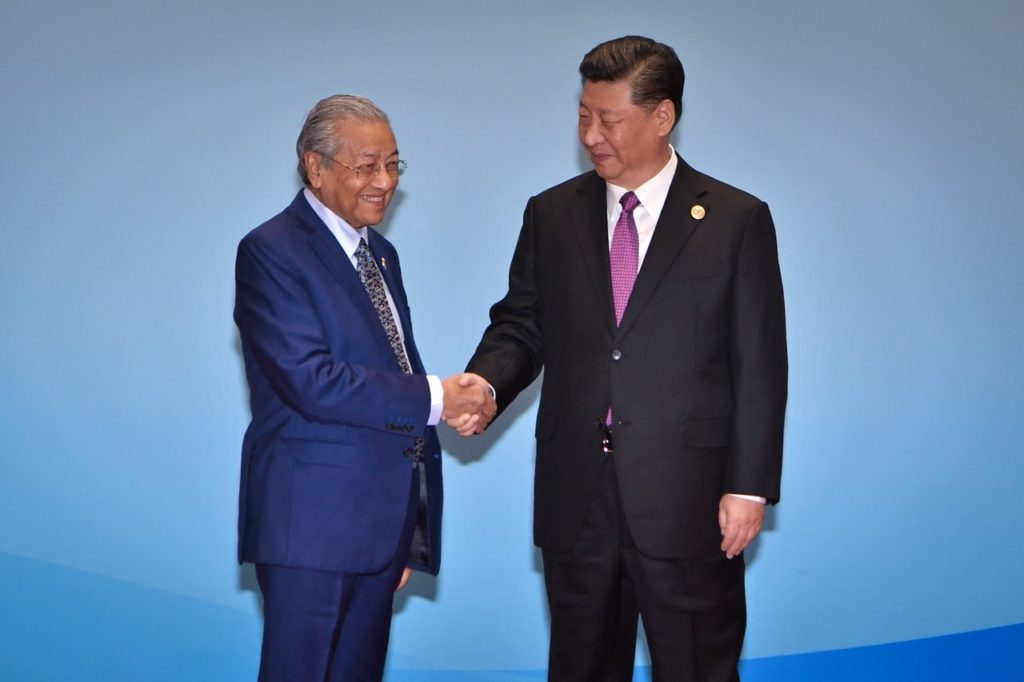

President Xi Jinping welcomes Prime Minister Mahathir to the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing. Photo: Bernama

Intense negotiations with China followed warnings from Mahathir after visiting China in August 2018 that Malaysia faced expensive penalties for ending the rail deal. China showed keen interest in pursuing the most important BRI project in the country and arguably in Southeast Asia. The April 12 announcement said the first two links of the rail project would now cost substantially less than the original price, with Malaysia claiming a savings of one-third and China claiming a somewhat lower figure. Both governments sought to sustain close relations during the difficult negotiations. Media reports in January said Mahathir and Chinese President Xi had established “a very special understanding” when they met in August that would ease any problems between the two states. Mahathir in February was the first world leader to confirm his attendance at China’s second BRI Forum in April, with the prime minister telling the media that Malaysia “valued” its relationship with China. China’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson put a positive spin on the renegotiation arguing that “achieving solutions through negotiations is what matters.”

Meanwhile, presumably in deference to China’s sensitivities, the Mahathir government has kept a low profile on Chinese suppression of Muslim Uighurs in the Xinjiang region, a notable contrast with the government’s strong rebuke of the Myanmar government’s suppression of Muslims in the Rohingya crisis. The Malaysian authorities did defy reported intense Chinese pressure to deport 11 Uyghur refugees to China and allowed them to seek asylum in Turkey. Mahathir in interviews and comments to the media also has adopted a more critical stance against the Trump government’s “unusually aggressive and inconsistent” foreign policies.

Developments in China-Myanmar relations

Three days before announcement of the dramatic cut in the cost of Malaysia’s rail deal with China, The Wall Street Journal reported on April 9 that Myanmar in the past year had been able, thanks to the assistance of a team of specialists led by US Agency for International Development (USAID) officials, to successfully renegotiate the scope of a Chinese-funded rail link, deep-water port, and industrial zone, thereby slashing the country’s debt to China. The report disclosed that the Myanmar government quietly reached out to US as well as British and Australian officials in seeking assistance to ensure that its contract with China didn’t have hidden traps enlarging Myanmar’s debt to China. The $7.3 billion Myanmar project was developed in 2015 between the previous military-dominated government and Chinese state-owned Citic Group. The plan called for a rail line from China to the town of Kyaukphyu, with the intent of transforming it into a major-deep-water port and industrial zone. After renegotiation, the Myanmar government under civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi announced the deal would be reduced to $1.3 billion, with just two jetties, with possible expansion later. The Journal disclosed the intention of USAID to offer similar assistance to other countries seeking to avoid onerous terms that come with Chinese-funded debt.

Xi Jinping demonstrated commitment to developing relations with Myanmar in receiving Myanmar Commander-in-Chief of Defense Services Senior General Min Aung Hlaing in Beijing on April 10. He said relations between the two countries have developed well in all areas, with unspecified “new progress” in jointly building the Belt and Road. The visit was Min Aung Hlaing’s fifth to China since becoming commander-in-chief. At the meeting, Xi paid special attention to assuring Myanmar that China supports the peace process of Myanmar and pays attention to the development of the political and security situation in the northern part of Myanmar and to enhancing border management between China and Myanmar.

Xi’s comments highlighted a now well-documented reality: contrary to China’s stated principle of noninterference, Beijing has become deeply involved in the Myanmar government’s efforts to seek peace with ethnic armed groups in conflict with the government, notably those along the frontier with China. Beijing also supports Myanmar against foreign criticism and in seeking a resolution of the crisis caused by the widely reported brutality of the Myanmar military against the Muslim Rohingya population.

A report by the United States Institute of Peace in 2018 notes that China’s approach is driven in part by its vast economic interests in Rakhine, “including a major port at Kyaukphyu, a planned special economic zone (SEZ), and a road, rail, and pipeline network to move energy and other materials and supplies from the Bay of Bengal through Myanmar to Yunnan Province.”

The report judged that on balance Myanmar viewed China’s involvement in the slow-moving peace process as constructive, though there remained serious doubt that Beijing would welcome a lasting peace. The latter risked ending China’s longstanding practice of using its influence with ethnic forces along the border as a source of leverage against Myanmar taking action against China’s interests, such as aligning closer with India or the United States.

While China is keen to “assert its leadership in regional affairs,” the report identifies a number of complicating factors. Most notably, Myanmar’s policy elites harbor continued distrust of China’s intentions and worry about over-reliance on China. Myanmar’s proud nationalism and colonial history mean that China’s influence would be strategically constrained and limited. In addition, Chinese businesses and nonstate entities involved in the commercial, business, and economic activities in Myanmar could complicate the government’s official position. The report, for example, notes that “illicit Chinese entities that traffic in Myanmar’s natural resources often act in concert with corrupt officials in the Myanmar government, military, and EAOs to fuel conflict in Kachin and Shan states. As a result, Chinese business actors provide revenue to conflict actors on both sides and help sustain Myanmar’s civil war.” While China may want to do more – and is increasingly expected to do so by the international community – the report’s conclusion is a sober reminder of the many factors beyond Beijing’s direct control that could hinder its strategic goals and diplomatic efforts in the peace talks in Myanmar.

China’s involvement in Myanmar’s internal ethnic conflicts stands in contrast to other non-traditional security challenges stemming from Myanmar. A new report, published by the International Crisis Group, examines the longstanding production of illicit drugs – especially methamphetamine – in Myanmar’s Shan state that have been supported for decades by armed militias in the region as well as by Myanmar’s military. The report notes that in the Mekong sub-region, the drug trade from the Shan state alone amounts to over $40 billion a year, facilitated by “good infrastructure, proximity to precursor supplies from China and safe haven provided by pro-government militias and in rebel-held enclaves,” all of which have made it a major regional, and increasingly global, source of high purity crystal meth.

With the inauguration of the new China-Myanmar Economic Corridor, increased cross-border and regional connectivity means that illicit drugs can become more readily and easily accessible. Better roads and a proposed high-speed rail from Kunming, Yunnan, to Kyaukphyu on the Rakhine state seaboard, for example, has helped bridge the link between south China to the Bay of Bengal. Thus far, China has remained relatively quiet about interfering in the illicit drug problem. According to the ICG report, China, where most chemicals needed to make meth originate, has almost never intercepted shipments crossing its border with Myanmar. It also finds that local government authorities in the region are often part of a wider corruption chain that span the border.

Cambodia: strengthening economic and military ties

While the increasingly authoritarian Hun Sen government faces growing visa and financial sanctions, withdrawn aid commitments, and other pressures from the US and other Western governments, its relations with China flourish. The Cambodian leader received top-level treatment during a trip to China in January. President Xi stressed China’s “close communications and coordination on global and regional matters” in calling for ever stronger economic ties in line with China’s BRI. Eight cooperative economic agreements were signed during the visit that dealt with BRI infrastructure projects. Hun Sen gave particular attention to a special economic zone in Sihanoukville, and to strengthening bilateral coordination in China-ASEAN negotiations and in discussions in the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation Mechanism.

In return for growing economic support from China, Hun Sen’s government since at least 2012 has been viewed by foreign experts as China’s reliable ally in ASEAN, repeatedly thwarting ASEAN from taking positions on South China Sea disputes that Beijing opposes. Military relations have grown in tandem. The Chinese Defense Ministry monthly press conference on Feb. 28 gave special prominence to the Cambodian Army commander’s visit to China and to the Dragon Gold 2019 military exercise held in Cambodia in March involving 252 Chinese soldiers helping Cambodia develop anti-terror capabilities.

Australia, New Zealand, Pacific Islands

The ferment in Australia’s relations with China over the past two years continued into 2019. In January, Beijing hosted Australian Defense Minister Christopher Pyne for his first visit to China since taking office in August. Chinese media said the visit demonstrated “a much needed change given the recent chill in China-Australia relations.” Nonetheless, the chill continued with China objecting in February to Australian Foreign Minister Marise Payne’s strong opposition to the Chinese firm Huawei playing a role in advanced telecommunications in Australia. Payne reiterated the Australian government position while visiting London in what Chinese media saw as an effort to encourage Great Britain to join the US-backed ban against Huawei. On March 26, former Foreign Minister Julie Bishop launched a broadside against the Australian business interests that lobby for a more accommodative policy toward China. She accused these interests of not understanding the risks Australia would face in allowing Chinese firms’ involvement in technology projects and other critical infrastructure. Beijing reacted positively to Payne’s announcement on March 29 that the Australian government is setting up an A$44 million foundation devoted to deepening understanding of and boosting relations with China.

New Zealand also reportedly banned Huawei from its next-generation wireless networks, which triggered China’s demand in February that a New Zealand Air flight to China turn around and return home as retaliation and a signal of worsening relations. Nevertheless, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern carried out successful talks with both Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang during a one-day visit, her first to China, on April 1. Chinese media positively highlighted the modest achievements of the visit; they also underlined concerns about New Zealand’s seeming acceptance of the US-led ban on Huawei, and Wellington’s efforts to work with the United States, Australia, and others to strengthen ties with Pacific Island countries to counter Chinese investment, infrastructure development, and security cooperation with Pacific Island countries.

Following Xi’s unprecedented visit to Papua New Guinea where he met leaders of the eight Pacific Island countries that recognize Beijing in November, Chinese media has had little to say about recent moves by the United States, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and others to guard against perceived adverse impacts of China’s rising influence in the Pacific Islands. Both the US and Australia have elevated the importance of the Pacific Islands within their respective foreign policy government organizations. The US National Security Council (NSC) created a new position of director of Oceania & Indo-Pacific Security and its director joined the NSC senior director for Asian affairs for a trip in March to Vanuatu and the Solomon Islands, along with representatives from Australia, New Zealand and Japan, reportedly to coordinate policies geared at “thwarting China’s strategic ambitions in the region.” Analysts at the Australian Lowy Institute judged that the US and Australia increasingly view China’s role in the Pacific Islands through a strategic lens. Reinforcing this trend, Conor Kennedy published an article in The Jamestown Foundation’s China Brief in March documenting how Chinese military analysts signal China’s intent to establish maritime strongholds in strategic locations including the Pacific Islands. John Lee of the Hudson Institute warned in similar terms of China following in the Pacific Islands the pattern China employed in using aid and commercial relations to gain agreement to establish a military base in Djibouti.

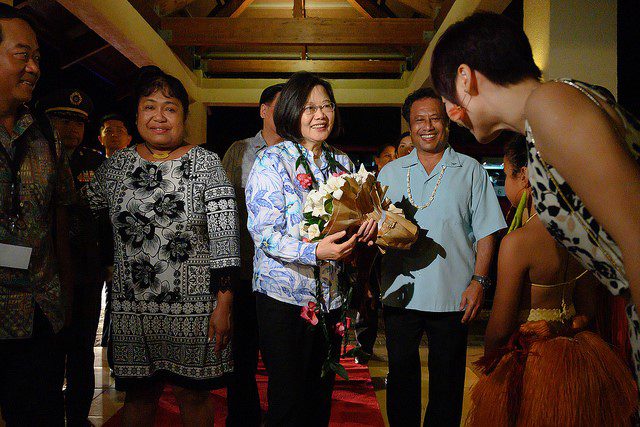

Against this background, Taiwan, an important aid provider to the six Pacific Island countries that maintain official relations with Taipei, sought and received more prominence in US efforts to build support for US objectives in the Pacific Islands at odds with Beijing. Secretary Pompeo sent a message to the 19th Micronesian Presidents’ Summit in Palau in February that highlighted Taiwan’s commitment to democracy and open societies, values he said were shared by the US and the five nations at the summit—Palau, Kiribati, the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) and Nauru (all but the FSM have official relations with Taipei). The US showed official support for Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen’s eight-day visit in March to Palau, Nauru, and the Marshall Islands when the US ambassador to Palau attended banquets hosted by the Palau leader and the Taiwan government marking Tsai’s visit. And the US approved Tsai’s one-day stopover in Hawaii during her trip to the region. At this time, Hawaii-based specialist Denny Roy issued a lengthy report emphasizing the strong common interests of Taiwan and US policies in countering Chinese influence in the Pacific Islands.

President Tsai being welcomed in Palau. Photo: Office of the President of the Republic of China (Taiwan)

Outlook

Whether Chinese relations with Southeast Asia and the nearby Pacific figure more prominently in Chinese foreign policy after the BRI Forum in late April is uncertain. Chinese leaders may be more likely preoccupied over the next few months with intensified competition with the United States and serious domestic concerns amid lackluster economic growth.

Jan. 16-Feb. 21, 2019: China conducts a military exercise that includes nearly 20 drills that draw from its navy, air force, and missile forces in the South China Sea as well as in the Pacific Ocean. The drills simulate combat situations at sea, repel advancing vessels, rescue efforts, and live-fire exercises, and are attempts to better integrate the People’s Liberation Army’s Rocket Force conventional and tactical units in its Southern Theater Command.

Jan. 22, 2019: Three PLA Navy escort vessels engage in a five-day visit to the Philippines on their return from an escort mission to the Gulf of Aden.

Jan. 22, 2019: Chinese Premier Li Keqiang meets visiting Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen to discuss the state of bilateral relations. They agree to cooperate on Cambodia’s infrastructure development and through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), jointly implement plans for the Sihanoukville Special Economic Zone, and strengthen Lancang-Mekong cooperation.

Jan. 29-Feb. 1, 2019: China, Laos, Myanmar, and Thailand jointly carry out the 78th Mekong River joint patrol. Four vessels from each of the four participant countries are involved in the joint patrol focusing on countering terrorist activities and other cross-border crimes.

Feb. 16, 2019: Singaporean Defense Minister Ng Eng Hen announces at the Munich Security Conference that negotiations for a code of conduct between ASEAN and China aimed at easing tensions in the South China Sea will begin later this month.

March 8, 2019: Vietnamese official reports that a Vietnamese fishing boat was rammed by a Chinese vessel near Discovery Bay in the Paracel Islands on March 6.

March 13, 2019: Former Philippine Foreign Secretary Albert del Rosario, former Ombudsman Conchita Carpacio Morales, and Filipino fishermen file a complaint against Chinese President Xi Jinping before the International Criminal Court for committing “crimes against humanity” in China’s systematic takeover of the South China Sea.

March 15, 2019: Communist Party Secretary of Sansha Zhang Jun announces plans to develop Woody Island and two smaller islets in the Paracels into a “national key strategic service and logistics base.”

March 26, 2019: Chinese Communist Party’s Minister of International Department Song Tao meets Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong to discuss bilateral cooperation. They agree to enhance relations through the BRI and through cultural and educational exchanges.

March 29, 2019: Vietnam’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs lodges a protest against China’s Hainan Province’s notice to hold live-fire drills in the Paracel/Hoang Sa islands.

April 1, 2019: Philippines presidential spokesperson announces that the Department of Foreign Affairs has filed a diplomatic protest against China regarding “the presence of more than 200 Chinese boats” that have been recorded near Philippines-claimed territory in the South China Sea between January and March.

April 3, 2019: China and the Philippines convene the Fourth Meeting of the Bilateral Consultation Mechanism in Manila. They agree to engage in dialogue to prevent and manage incidents at sea, to build mutual trust and confidence, and to explore prospects for maritime economic cooperation.

April 17, 2019: Preliminary results from Indonesia’s general election show incumbent Joko Widodo winning over Prabowo Subianto in the presidential race.

April 19, 2019: Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad announces revival of the $34 billion Bandar Malaysia development project that was suspended in 2017. The Chinese-backed rail and property development project is described by Mahathir’s office as “a significant contribution to the Belt and Road Initiative,” and integral in fostering long-term bilateral relations between Malaysia and China.

April 23, 2019: Thai officials announce that Thailand will sign a memorandum of cooperation with Laos and China to increase regional connectivity and infrastructure development.

April 25-27, 2019: China convenes the second Belt and Road Forum in Beijing with a joint statement signed by China and 37 other countries in attendance. A number of infrastructure projects ranging from sea ports to railways are highlighted for their impact on strengthening land and maritime trade routes that would forge stronger economic ties between Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and Africa.