Articles

China’s recently recognized position as Southeast Asia’s leading power faces growing challenges from efforts of the Biden administration to counter Chinese ambitions and advance US regional influence. Beijing has stuck to practices of strong diplomatic engagement, economic enticement, and a range of coercive measures that have been broadly successful in the past but seem to have failed badly in the Philippines, now moving into the US orbit.

Measuring Competition for Regional Leadership

After more than a decade of growing Chinese influence, leading to perceived greater dominance in Southeast Asia and gradual US decline, two years of Biden administration activism have increased US influence and challenged China’s recent ascendance. Southeast Asia has emerged as the Indo-Pacific sub-region most in play in the acute China-US regional rivalry, with no clear sense of which power will prevail.

An authoritative study published by the Asia Society providing the findings of deliberations by leading regional and US experts emphasized China’s ascendance. A report by CSIS summarizing the strengths and weaknesses of recent polls about the competition between the US and China in Southeast Asia generally agreed on China’s prominence in terms of economic power and to a degree in strategic power, but saw the United States as more popular than China in the region.

Beijing’s mix of economic inducements, which deepen regional dependence that is often used as leverage to compel Southeast Asian compliance, and its overt and covert use of coercive measures to counter Southeast Asian resistance have allowed China to increasingly have its way in South China Sea disputes and other sensitive matters. China’s advantages relative to the United States include common borders and proximity, control of headwaters of major rivers of utmost importance to Southeast Asia, a lasting position as leading trader and largest or second largest source of financing for infrastructure, and deep investment by Southeast Asian states in China while China’s investment in ASEAN states grows substantially.

China also influences and controls significant regional transportation, communications, and other infrastructure, and large segments of the ethnic Chinese diaspora and local media. It accommodates corrupt practices by regional leaders. Regional economies often depend on large numbers of Chinese tourists and students, now returning after the lifting of COVID restrictions.

The Asia Society and CSIS studies cited the Lowy Institute’s Asia Power Snapshot of April 2023 covering Southeast Asian countries, which offered an historical perspective to conclude that in over five years China’s influence has soared, largely at the expense of the United States. Nevertheless, the Asia Society report duly assessed US strengths in military networks across the region, strategic counterbalancing against Chinese expansionism, foreign investment, and the large role of US businesses and non-government as well as government cultural and educational exchanges.

Perhaps the most important advantage the United States has in dealing with China’s rising influence is the synergy that flows from the Biden administration’s coordination of its efforts with those by allies and partners to work with the United States and among themselves and others outside the region to build regional resilience and deter the danger posed by increasing Chinese regional expansionism and dominance. Seemingly reflecting this development in was the Lowy Institute’s annual Asia Power Index 2023 covering 22 Indo-Pacific countries including all 10 ASEAN members. The Index was available soon after the release of the Snapshot. It pointed to a surprising pause over the past year in China’s rising regional influence and some increase in that of the US. It claimed that China’s Economic Capacity—a measure of core economic strength and ability to use the economy to political advantage—is at its lowest level since 2018, with the United States again leading on this measure. It forecast that China will remain second to the US in regional influence for at least the rest of this decade.

Official Chinese media and leadership commentary, along with some international specialists, see ever-stronger negative consequences for Chinese interests from the growing array of US-ally-partner arrangements establishing what the Biden government calls “positions of strength” allowing for more effective efforts to counter adverse Chinese challenges. Australian specialists advised recently that AUKUS is not just a trilateral Australia, United Kingdom, US agreement involving nuclear-powered submarines, but it also aims to “transform the Indo-Pacific order” in ways adverse to China’s ambitions. Beijing has long viewed the Quadrilateral dialogue (The Quad) —involving the US, Australia, India, and Japan — as working actively against Chinese regional interests. Strong Chinese criticism followed the summit of the Quad leaders in Japan in May. Beijing’s criticism also took note of the announcement in May of progress of the United States and 13 other countries including several from Southeast Asia in seeking to lessen dependence on China in their supply chains under the rubric of the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework.

Beijing has long attacked the G7 and NATO for their growing involvement in the Indo-Pacific, including Southeast Asia. The G7 summit in Japan in May featured the attendance of eight other countries, two from Southeast Asia (Indonesia and Vietnam) and one from the Pacific Islands (the Cook Islands) representing the Pacific Islands Forum. The Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson issued a detailed statement condemning the G7 leaders’ communique criticizing China’s actions over the South China Sea and other issues sensitive to Beijing.

Figure 1 Chinese Defence Minster Li Shangfu salutes the audience before delivering a speech at the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore on Sunday. Photo: AFP

Speaking at the Shangri-La Dialogue in June, China’s Defense Minister Li Shangfu rebutted Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin’s complaint about China’s dangerous aerial intercepts of US aircraft over the South China Sea and warned the region of US-led “NATO-like alliances in the Asia Pacific.” Official Chinese commentary was shrill in opposition to the criticism of China at the NATO summit in Lithuania July 11-12. China was particularly critical of the attendance of “the Indo-Pacific Four”—Australia, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea—arguing they were all becoming more active in support of the US “Indo-Pacific Strategy.”

Strident anti-NATO rhetoric overshadowed Chinese claims of stability in the Asia-Pacific at the ASEAN-led foreign ministers’ meetings in Indonesia July 12-14. Substituting at those meetings for recently appointed and then abruptly removed Chinese Foreign Minister Qin Gang, China’s Director of the Central Commission for Foreign Affairs and Foreign Minister Wang Yi warned of US-led NATO expansion into Southeast Asia and the Asia-Pacific. Other official commentary charged the US was using these measures to promote “containment” of China.

Authoritative Chinese commentary on the Biden government’s effort to solidify the trilateral US-Japan-South Korea alliances at a remarkable summit meeting at the presidential retreat at Camp David on Aug. 18 saw wide-ranging negative implications for China throughout the Indo-Pacific, including Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands. In particular, the summit saw South Korea, an influential power in these areas, increasingly joining with the US and Japan as well as leading NATO powers in countering Chinese expansionism while cooperating in economic and trade measures to counter Beijing’s adverse practices.

Most recently, initial Chinese media commentary reacted warily to the White House announcement on Aug. 28 that President Biden would visit Vietnam on Sept. 10 amid reports that the two countries would upgrade their relationship.

China’s Regional Leadership

Beijing sustained strong efforts in Southeast Asia and elsewhere in the so-called “Global South” to portray China as a major source of strategic stability and economic growth with comprehensive global governance plans supportive of interests of developing countries and opposing the United States. Nevertheless, the expected boost in 2023 in Chinese trade with ASEAN and the four other members of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) free trade pact (Australia, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea) failed to materialize. China-ASEAN two-way trade hit $447.3 billion in January-June, down 1.5% year-on-year. Chinese exports to Southeast Asia fell by 21.43% in July compared with a year earlier.

Wang Yi and Chinese official commentary emphasized the positive during the ASEAN-led foreign ministers’ meetings in Jakarta in July. On the sidelines of the China-ASEAN foreign ministers’ meeting on July 13, Wang echoed Chinese commentary lauding the 20th anniversary of China signing the ASEAN Treaty of Amity and Cooperation, the first foreign power to do so. He highlighted building an even closer China-ASEAN community and reaching important common understandings with Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia on what China calls a community with a shared future. He praised the Belt and Road Initiative in Southeast Asia, and asserted that the value of China-ASEAN trade in 2023 was expected to exceed $1 trillion. He highlighted progress on reaching version 3.0 of a China-ASEAN free trade agreement.

On other matters, negotiations were held in preparation for a new multinational military exercise Aman Yuyi-2023 involving China and five Southeast Asian countries in 2023. China also began construction of a $10 billion canal connecting the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region with Southeast Asia.

South China Sea Issues Apart from the Philippines-China Furor

Figure 2 US Secretary of State Antony Blinken shakes hands with Chinese Communist Party’s foreign policy chief Wang Yi during their bilateral meeting on the sidelines of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in Jakarta, Indonesia, Thursday, July 13, 2023. Dita Alangkara/Pool via Reuters

While Chinese media duly reported Wang’s talks with US Secretary of State Antony Blinken at the meetings in Indonesia, they criticized Blinken’s purported efforts during the sessions to drive a wedge between China and Southeast Asia over territorial disputes in the South China Sea. Blinken earlier criticized China’s refusal to meet with Austin in Singapore or with other senior US military officials to discuss a close mid-air encounter between a US surveillance aircraft and a Chinese jet fighter over the South China Sea on May 26.

At the meetings in Indonesia, Wang Yi said China welcomes the successful completion of the second reading of the draft text of the Code of Conduct (COC) in the South China Sea, supports the guidelines reached in July to accelerate the conclusion of the COC, and stands ready to continue to play a constructive role for an early conclusion of the COC.

In other developments, Indonesia’s defense chief noted that an agreement was reached with ASEAN counterparts to hold the first ASEAN joint military drills in the South China Sea later in 2023. Vietnam on May 25 demanded that China’s survey ship and escort vessels leave waters near Vanguard Bank claimed by Vietnam but challenged by China where Vietnam has been carrying out exploration for oil and natural gas. Vietnam also protested China and the Philippines deploying buoys in South China Sea areas claimed by all three countries. The CSIS Asia Maritime Initiative reported a big increase over the past year in governments supporting the July 2016 South China Sea arbitral ruling which voided China’s expansive claims to the South China Sea. Since November 2022, 16 governments including India and 15 European countries have moved from positively acknowledging the ruling to fully supporting it as legally binding. Significantly, none of the Philippines’ Southeast Asian neighbors have formally endorsed the ruling as binding.

Most recently, the Chinese embassy in Indonesia and official Chinese media criticized a US Defense Department statement marking Defense Secretary Austin’s meeting with Indonesia’s defense minister in the United States on Aug. 24 for asserting that the two ministers “shared the view that the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) expansive maritime claims in the South China Sea are inconsistent with international law as reflected in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.” In rebuttal, the Chinese embassy and supporting media said “We’re informed by the Indonesian side that what the US side described is not true.” They noted that “no such content can be found in the news release by the Indonesian side on the same meeting.”

Figure 3 An undated photo of the amphibious BRP Sierra Madre the Philippines have used as an outpost in the South China Sea. Photo: Jay Directo via Getty Images

As discussed in the Philippines section below, a dramatic confrontation took place on Aug. 5 near the Philippines outpost on Second Thomas Shoal between large Chinese Coast Guard ships using threatening maneuvers and water cannons to block two much smaller Philippine supply ships seeking to reach the outpost. The incident, video recorded and released by the Philippines Coast Guard, prompted a barrage of harsh criticism of Chinese coercive behavior by the Philippines, the United States and their allies and partners, representing a new low in Philippines-China relations and a stronger international effort against Chinese bullying in the South China Sea. Chinese officials and commentary were preoccupied with defending China’s actions in the following weeks.

Philippines Rebuke China’s Coercion, Embrace Closer US, Allied Ties

Chinese officials and media commentary in 2023 registered growing concern with the steady decline in relations with the Philippines as President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., while voicing support for good relations with China, markedly strengthened alliance relations with the United States as well as closer ties with Japan and Australia; all were seen by Beijing in strongly negative terms as attempting to contain China. Chinese criticism of Philippine actions put much of the blame on the United States, though Manila was also seen as willingly joining in perceived anti-China measures for its own reasons. There were repeated warnings of unspecified negative consequences but Chinese coercion against the Philippines remained covert, notably in swarming maritime militia, coast guard, and naval forces in June to dissuade the Philippines from resuming oil and gas exploitation in the disputed Reed Bank of the South China Sea.

Beijing criticized Marcos’ joint statement with President Biden on May 1, in which the Philippines aligned more closely with US positions opposing China on Taiwan, the war in Ukraine, and the US-Australia-India-Japan Quadrilateral Dialogue. Prominent Chinese South China Sea expert Wu Shicun saw the “ever deepening US-Philippines security cooperation” as “a main driver of militarization of the South China Sea.” In a step unwelcome in Beijing, the first-ever quadrilateral defense leaders meeting, involving the Philippines with the United States and fellow US allies Japan and Australia, occurred on the sidelines of the Shangri-La Dialogue in June.

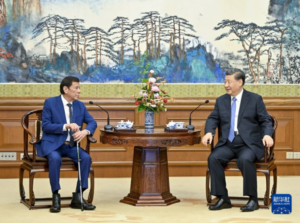

Beijing did welcome China-friendly visitors to China, notably former Presidents Gloria Arroyo in April and Rodrigo Duterte in July. Xi Jinping met Duterte, praising his “strategic choice to improve relations with China.” In late June, Duterte said that the Chinese ambassador in the Philippines told him that the Philippines will be a target of Chinese attack if it allows US forces to use bases in the Philippines to launch military strikes against China.

Figure 4 On the afternoon of July 17, 2023, President Xi Jinping met with former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte at the Diaoyutai State Guesthouse in Beijing. Photo: Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the United States of America

The Aug. 5 confrontation at Second Thomas Shoal prompted across-the-board condemnations from Philippine foreign policy, coast guard and military leaders with President Marcos leading the pack in putting aside any ambiguity in his stance against China’s actions. Marcos strongly attacked Beijing’s argument that the Philippine supply ships were bringing in construction supplies to make permanent the outpost, a long grounded and rusting ship, breaking an agreement to eventually remove the grounded ship. He said there was no such agreement and if there were such an accord he declared it rescinded.

Subsequently, the Philippines Coast Guard suspended a “hotline” with its Chinese counterpart begun during the Duterte government, arguing “we didn’t gain anything from this.” During a meeting with the Vietnamese ambassador, President Marcos urged discussions on a maritime cooperation agreement with Vietnam. The president also appointed former foreign minister and now ambassador to Britain and Ireland Teodoro Locsin as the president’s “Special envoy” to deal with unspecified “special concerns” with China. Locsin was the most outspoken critic of China’s practices in the previous Duterte government.

The US State Department reacted quickly to “stand with our Philippine allies” and Defense Secretary Austin followed with promises of “iron-clad” support. There were prompt strong statements against China’s behavior by Japan, Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the UK, and the European Union. Other reports indicated that recently improved US intelligence sharing with the Philippines had assisted the Philippines in its operations. Philippines Coast Guard observers were ready to create a good quality video of the incident to show to viewers at home and abroad the comparatively tiny supply ship being doused by the much larger Chinese Coast Guard ship.

The resulting outrage in the Philippines put pro-China advocates in the country on the defensive, with a Coast Guard official targeting pro-China Filipinos as “traitors.” Chinese commentary was also on the defensive, actively attempting to defend Beijing’s actions. Frequent Chinese official commentary continued to repeatedly warn Manila of usually unspecified negative consequences for its alignment with the United States and its allies and partners against China’s interests. Wang Yi was sent to Singapore, Malaysia, and Cambodia on Aug. 9 to boost “strategic communication” that focused on giving China’s side of the story about the dispute with the Philippines.

It was disclosed that one of the two Philippine supply ship containing routine supplies for the troops at the outpost was eventually allowed to reach the outpost. The other with construction supplies to reinforce the outpost was turned away, with the reported expectation that it would attempt to reach the outpost in the coming week.

The new supply mission encountered resistance from Chinese Coast Guard vessels and Maritime Militia boats as it approached the outpost on Aug. 22. Over a period of five hours, the Coast Guard ships harassed two supply ships and two accompanying Philippines Coast Guard vessels, surrounding the latter as the small supply ships reached shallow waters and landed at the outpost. Once deliveries were made, all Philippine vessels departed. The prolonged encounter was publicized by reporters invited to accompany the crew on the Philippines Coast Guard vessels, a step said by the reporters’ news items to represent a new strategy by the Philippines government to highlight Beijing’s “increasingly aggressive actions in the South China Sea.” The reports added that throughout the encounter a US Navy surveillance aircraft flew overhead as the Chinese ships blocked and harassed the Philippine vessels. In response to questions about US involvement, the US Embassy issued a general reassurance that US military activities in the Philippines are conducted “in full coordination with our Philippine allies.”

Concurrently, Philippine officials disclosed on Aug. 20 that exercises by warships involving three aircraft or helicopter carriers from the United States, Japan, and Australia would hold joint drills in the South China Sea near the Philippines, with the commanders meeting Philippine officials after the exercises. As it turned out, the Philippines unexpectedly sent a warship to join the allies in the exercise, a further demonstration of Manila standing with the allies in the face of Chinese intimidation and coercion.

China-Myanmar Relations in the Spotlight Again

Prior to the sudden removal from his post, Chinese Foreign Minister Qin Gang stepped up engagement with Myanmar in May. He met Noeleen Heyzer, the UN Secretary-General’s Special Envoy on Myanmar. Qin expressed China’s support to assist Heyzer’s mediation efforts, as well as ongoing ASEAN-led efforts and the region’s Five Point Consensus on Myanmar. Qin said that “we need to act prudently and pragmatically to prevent escalating tensions and the spillover of the crisis.” He added that “more than any other country,” China hopes that Myanmar can achieve stability, “as it is a close neighbor.”

Following the meeting with Heyzer, Qin visited Ruili, a border town in Yunnan province, and urged local officials to help maintain the stability of China-Myanmar borders. He then proceeded on an official visit to Myanmar, meeting with the junta leaders in the capital of Naypyitaw, the first such meeting since Myanmar’s coup in February 2021. The trip comes amidst growing ASEAN frustration with stalled progress in Myanmar’s cooperation on and implementation of the Five Point Consensus. At the same time, international pressure is also mounting as clashes between the junta and resistance groups have become more frequent with increasing levels of violence and civilian deaths. Local media reported that Qin and Myanmar’s junta leader Min Aung Hlaing met to discuss the country’s political situation as well as trade and investment. China’s diplomatic approach appears to strengthen its formal ties with the junta, all the while mediating and engaging with ethnic minority response groups as well. China’s special envoy on Myanmar has been in contact with the armed ethnic minority groups along the Chinese border since December in attempts to mediate.

China-Indonesia Summit

Indonesian President Joko Widodo visited Chengdu and met in July with President Xi for a bilateral summit. The talks between the two leaders centered on deepening business and trade ties, given the significance of bilateral economic activities. Indonesia’s trade data show that two-way exchange stood at $133.7 billion in 2022. China invested $8.2 billion last year, making it Indonesia’s second-largest foreign investor (after Singapore). Beijing’s investment in Indonesia throughout the first half of 2023 amounted to nearly $4 billion. The discussion also focused on stepping up cooperation and investment in public health and research and technology in renewable energy. Both sides also inked agreements to exchange knowledge and experience for Indonesia’s capital project as it plans to relocate its capital city from heavily congested Jakarta to Nusantara on Borneo in 2024.

Singapore Clarifies its Stance Amid US-China Competition

A recent article published by the Washington Post asserted that the political alignment of Lianhe Zaobao, Singapore’s largest Chinese-language newspaper, is largely pro-China, prompting Singapore’s Ambassador to the United States Lui Tuck Yew to clarify the city-state’s position on intensifying US-China competition. The article, published in late July, finds that Lianhe Zaobao “routinely echoes some of Beijing’s most strident falsehoods, including denying evidence of rights abuses in Xinjiang and alleging that protests in Hong Kong and in mainland China were instigated by ‘foreign forces.’”

In Lui’s response via a letter to the editor, he explained that “Singapore’s mainstream media, including Lianhe Zaobao, reflect our distinct societal concerns, cultural history and perspectives. They report local and global news for Singaporeans and play a crucial role in preserving the voices of our multi-cultural communities.” He added that it was “misguided for American news outlets to expect Zaobao to resemble the Washington Post or for Singapore to follow either the US or China,” while emphasizing that Singapore does not pick sides in the rivalry. The statement echoed senior Singaporean leaders’ views. Earlier in May, Singapore’s Deputy Prime Minister Lawrence Wong, who is widely expected to become the next prime minister, stated that Singapore “cannot prescribe policy for the US and China;” instead it is a “friend to both China and America, and we want to stay friends with both sides.”

Vietnam-China Relations—Warily Cordial

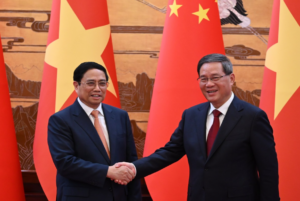

Vietnam’s relations with China remained cordial in the wake of a visit to Beijing in October by General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong, Vietnam’s top leader, in October, the first foreign leader to visit China to personally congratulate Xi on winning a new five-year term at the 20th Chinese Communist Party Congress. In June, Vietnam’s prime minister made a four-day visit to China. Both sides routinely emphasized their extensive common ground while managing differences without disrupting regional stability, especially in the South China Sea.

Figure 5 Vietnamese Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh (left) with Chinese Premier Li Qiang in the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on Monday. Photo: EPA-EFE

Nonetheless, as noted above, Vietnam protested China’s dispatch in May-June of a survey ship and escorts to harass Vietnamese-backed oil and gas exploration activities near Vanguard Bank in the disputed South China Sea. China put heavy pressure on Vietnam in the same area five years ago, forcing Vietnam to terminate exploration activities at that time. Vietnam has also shown its independence from China in reaching an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) delimitation agreement with Indonesia, reflecting their respective claims in the South China which are at odds with China’s wide-ranging claim. President Marcos’ meeting with the Vietnamese ambassador in August signaled that Manila and Hanoi will start discussions on a maritime cooperation agreement in hopes of stabilizing tensions in the South China Sea. Marcos reportedly underscored the need for such cooperation as Beijing escalates tensions in the South China Sea.

Vietnam also showed independence from China in welcoming the US aircraft carrier Ronald Reagan to Vietnam after having hosted one of Japan’s largest naval combatants. Both ships were exercising in the South China Sea, demonstrating their opposition to Chinese coercive intimidation.

Vietnam’s sensitivity regarding China’s South China Sea claim showed as Hanoi banned the Hollywood movie Barbie because it allegedly portrayed China’s nine-dash line claim, which is at odds with Vietnam’s claim. The other main disputant of China’s claim, the Philippines, did not see the map shown in the movie as grounds for banning the film.

Beijing reacted cautiously to rumors and then final confirmation that President Biden would visit Hanoi on September 10. Initial Chinese commentary focused on US intentions to use improved relations with Vietnam to increase its regional influence and contain China. Global Times cited Chinese experts in Chinese government think tanks and universities for the view that the visit will have a “limited impact” on China as Beijing leaders have strong “mutual trust” with their Vietnamese counterparts. The reports took note that the US and Vietnamese leaders might raise their relationship to the level of “strategic partnership” and did not anticipate relations being upgraded to a comprehensive strategic partnership as was reported by foreign media on September 2. China has long had a solid position in this highest rung of Vietnam’s relationships, with Hanoi recently establishing this status with South Korea and Australia.

Thailand-China Relations—Treading Water

Foreign assessments often depicted China as having gained influence in relations with Thailand at the expense of the United States over the past decade of Thai military rule and partial return to civilian leadership. Official Chinese commentary duly noted that the surprise victory of the newly formed Move Forward Party and its Harvard- and MIT-educated leader Pita Limjaroenrat in the general elections in May might lead to a change and some turn away from China.

China remained Thailand’s largest trading partner with trade in 2022 valued at $107 billion, representing 18% of Thailand’s total trade. China was also the top investor with $2.3 billion invested in Thai industries in 2022. Despite the longstanding US alliance with Thailand and its large-scale signature military exercise Cobra Gold, China has markedly increased military ties with Thailand. It has surpassed the United States as the primary supplier of military equipment to the country.

Against this background, official Chinese media have reported generally without comment what has turned out to be a prolonged process in approving a new government after elections in May. Chinese commentary only recently raised complaints about the negative economic costs for Thai businesses and foreign businesses working in Thailand because a government has not yet been approved. In the end, China Daily noted controversy surrounding the selection of the new prime minister but judged his government could now fill the vacuum of government leadership that has complicated economic development.

Cambodia-China Relations—Uninterrupted Progress

The government leadership transition in August from long-serving Prime Minister Hun Sen to his eldest son Hun Manet prompted nothing but effusive official Chinese commentary depicting ever-stronger economic, military, and political relations. Chinese media focused on major projects done under the rubric of the Belt and Road Initiative, while foreign coverage added that China’s military base in Cambodia is nearing completion. Chinese commentary duly noted the new prime minister’s undergraduate studies at West Point and a PhD in economics from a university in England, but it averred that the deeply rooted Sino-Cambodia cooperation seen for over two decades will advance smoothly. Beijing media relied on none other than Hun Sen himself to write the most important commentary marking the leadership transition. It advised that the former prime minister will remain actively involved in policymaking as leader of the country’s ruling political party.

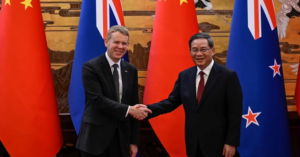

Chinese advances in this reporting period included the visit to Beijing of the prime minister of New Zealand in June and the prime minister of the Solomon Islands in July. In power since January, Prime Minister Chris Hipkins adopted a public posture notably less critical of China than previous New Zealand prime minister and also less critical than the United States and its other allies and partners. Beijing appreciated the new leader’s emphasis on advancing economic relations while playing down differences. How far this moderation will go remained to be seen as concurrent New Zealand strategy documents sustained a tougher approach to Chinese behavior more in line with US policies.

Figure 6 New Zealand Prime Minister Chris Hipkins (l) and Chinese Premier Li Qiang shake hands at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China, June 28, 2023. Photo by Pool/ Reuters

Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare’s China visit featured an upgrading of relations to a “comprehensive strategic partnership,” with Xi Jinping promising deeper cooperation in all areas of the relationship. Beijing media praised Sogavare for resisting the “constant pressure” from the United States and Australia particularly regarding a security agreement the country signed with China in 2022. It noted that one of the new agreements signed during the visit involved “deepening police cooperation” with China.

In the process of criticizing US policy in the Pacific Islands, Chinese commentary underlined impressive US activism over the past year. It adopted a low-key posture, maintaining that Beijing is not interested in engaging in a geopolitical contest with the United States in the Pacific Islands region. The defense pact with Papua New Guinea signed in May was said to give the US military access to the country’s ports and airports. Renewed US security related pacts with Palau, Micronesia, and the Marshall Islands were noted as was Secretary of State Blinken’s meeting with representatives of 14 Pacific Island countries when visiting the region in May. Other US advances included a deal with Papua New Guinea, allowing the US Coast Guard to board the country’s ships to help patrol for illegal fishing, with Chinese fleets as a leading target. Micronesia and Palau are expected to go forward with plans for the United States to build military bases on their territories.

Another advantage the US has is close relations with Australia and New Zealand, both members of the Pacific Islands Forum, the region’s leading decision-making group. Both have been active in security matters in the Solomon Islands, with Australia also active in Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea, and Kiribati.

Outlook

Beijing depicts a pattern of US initiatives challenging China’s position in the region as having momentum and likely to continue during the Biden administration. The ASEAN summit and the G20 gathering in September are two platforms where US-China competition will likely take center stage yet again. Among uncertainties is China’s capacity for effective responses in these venues and US resolve given Biden’s continued mediocre public approval ratings and the prospect that Donald Trump will win the 2024 election with an America First platform that could complicate and weaken US alliances and partnerships.

May 1, 2023: Chinese Foreign Minister Qin Gang meets UN Secretary-General’s Special Envoy on Myanmar, Noeleen Heyzer, in Beijing. Qin reiterates China’s position to respect Myanmar’s sovereignty and that China is willing to provide support to ASEAN and UN’s mediation efforts.

May 2, 2023: Chinese Foreign Minister Qin Gang visits the China-Myanmar border areas in southwestern Yunnan province. Qin calls for local authorities in the border town of Ruili to maintain friendly cooperation with Myanmar.

May 17, 2023: Chinese Premier Li Qiang meets Singapore’s Deputy Prime Minister Lawrence Wong in Beijing. The two sides discuss furthering bilateral cooperation in such areas as energy, digitalization, sustainability, and increasing people-to-people exchanges.

June 2, 2023: China and Singapore defense establishments agree to set up a secure, bilateral hotline to strengthen high-level communication between their defense leaders.

June 13, 2023: Eurasia Group reports on new survey results regarding Asia’s views on US and China’s influence in the region. The survey of 1,500 adults from Singapore, South Korea, and the Philippines finds that Singaporeans are less worried about rising great power tensions and have a more balanced view of US-China competition, compared to others. Most respondents across the three countries have a positive view of US influence, with Singaporeans being more evenly divided: 63% of those surveyed think China’s influence has been positive, while 64% think the same of the United States.

June 22, 2023: Indonesia, host of ASEAN’s first-ever joint military drills in the South China Sea due in late September, announces that it will move the location of the regional exercise to the South Natuna Sea, closer to Indonesian waters.

July 8, 2023: Philippine military raises concerns about the increasing presence of Chinese coast guard ships and militia vessels in the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone, specifically near Sabina Shoal, Second Thomas Shoal, and the Reed Bank. The Philippines’ air surveillance missions also report that Chinese coast guard vessels are shadowing and firing water cannons at the Philippine coast guard ships escorting boats on a resupply mission for Philippine naval soldiers stationed in the Second Thomas Shoal.

July 10-14, 2023: Southeast Asian foreign ministers convene in Jakarta for the region’s semi-annual meeting and for their meeting with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi. ASEAN and China agree on the “Guidelines for Accelerating the Early Conclusion of an Effective and Substantive Code of Conduct” to expedite the negotiations. In addition, ASEAN and Chinese diplomats engage in discussions to more fully implement the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a trade deal involving 15 countries in the region.

July 28, 2023: Chinese President Xi Jinping meets Indonesian President Joko Widodo in Chengdu. Both leaders agree to enhance bilateral cooperation in the areas of public health, research and technology, as well as regional security and development.

Aug. 10-13, 2023: Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi is on a four-day, three-country visit to Southeast Asia that includes Singapore, Malaysia, and Cambodia. The tour signals China’s intention to shore up diplomatic relations and deepen engagement with Southeast Asia. In Singapore, Wang’s meetings and discussion with Singapore’s leaders conclude with Singapore’s in-principle support for China’s interest in joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

Aug. 29, 2023: China’s People’s Liberation Army Southern Theater Command and the Singapore Armed Forces announce that they will conduct “Exercise Cooperation,” a two-week joint exercise that will commence in mid-September and focus on tactical training, and small arms live firing, among other activities.