Articles

Chinese enhanced activism in Southeast Asia in this reporting period focused on countering Biden administration efforts to enhance influence in the Indo-Pacific. The Chinese government intensified its depiction of the United States as disrupting regional order and portraying itself as the regional stabilizer. Beijing’s effort faced complications and uncertain prospects as Chinese military forces in August launched large-scale provocative shows of force amid strident media warnings targeting the United States over Taiwan.

Countering US Initiatives

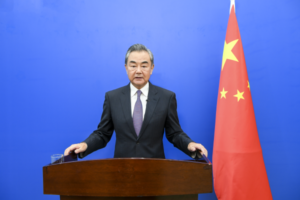

Beijing’s activism in Southeast Asia in mid-2022 featured strong diplomatic efforts led by Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi and backed by authoritative media and included a summit meeting with Indonesia’s president in China. Beijing strengthened regional ties through proposals for greater security involvement along with extensive economic and diplomatic involvement. These proposals were in line with Xi Jinping’s new Global Security Initiative complementing his Global Development Initiative, both of which are especially appealing to developing countries.

As shown in the previous Comparative Connections, China maintained a focus on depicting the United States in Southeast Asia as a disruptive force at odds with regional interests in cooperative economic development led by China as regional stabilizer. The focus was complicated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and China’s siding with Russia against US sanctions and US military support for Ukrainian resistance. Chinese diplomacy and supporting publicity for several months was preoccupied with Russia-Ukraine-US issues and gave top priority in the region to lobby for opposition to US actions against Russia. The anti-US message aimed to condemn what was seen as an emerging US-led regional military alliance in the Indo-Pacific and to warn Asian countries against bandwagoning with the United States on Russia-Ukraine and regional matters. The results of China’s effort were mixed. Regional governments carefully avoided major controversy associated with choosing sides in UN votes and other policies regarding the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

Chinese Initiatives

At the same time, China moved forward with important initiatives reflecting Beijing’s expanding influence in Southeast Asia and nearby areas. In line with Xi Jinping’s global objective of a shared destiny of mutually beneficial development and peace, Beijing has long argued that its vision of Chinese-ASEAN ties stands in contrast with the disruptive policies of US leaders. The United States is portrayed as creating divisive blocs to compete with China for leadership in Southeast Asia and the broader Indo-Pacific region. Xi launched his Global Security Initiative in a keynote speech to the annual Boao Forum for Asia in April; he depicted the Initiative as upholding “common, comprehensive, cooperative and sustainable security” and opposing the US “Cold War mentality.” According to subsequent explanations, Xi’s initiative was in line with new types of security relations that are said to replace confrontation, alliances, and zero-sum competition with dialogue, partnerships, and win-win cooperation. When married with Xi’s Global Development Initiative, the Asia Society concluded that the new security proposal reinforces China’s image as “an empathetic friend of the global south, including Southeast Asia, and fellow developing countries seeking to advance ‘greener and more balanced development through open and inclusive partnerships.’” Xi subsequently highlighted his new security initiative among other regional groups and China lobbied Southeast Asian and other developing countries to explicitly endorse the proposal.

The substance of Chinese enhanced security involvement has come in usually incremental but sometimes dramatic efforts to advance security ties in line with robust Chinese economic and diplomatic relations throughout the region and in regional organizations. Beijing’s ambitions showed notably in China’s security agreement with the Solomon Islands in May and a concurrent proposed security and development pact with 10 Pacific Island nations, discussed at the end of this chapter.

US Initiatives and China’s Responses

This section explains how Beijing developed and intensified its argument that the United States was the main disrupter and threat to regional peace and development and China was the leading regional stabilizer and benefactor. And it assesses how China’s shows of force and threats targeting Taiwan, the United States, and allies complicated and compromised China’s purported image as a regional stabilizer.

As President Biden and senior administration leaders increased involvement in the Indo-Pacific region with a series of initiatives beginning with the US-ASEAN summit in May, Beijing stepped up diplomatic lobbying and media warnings in response.

Biden Summit with ASEAN Leaders, May 12-13

Critical Chinese media focused on perceived shortcomings of the summit and depicted the president as trying to keep pace with Beijing’s much more active and substantive diplomatic and economic relations with the region. Biden’s pledge of $150 million to aid regional countries and the appointment of an ambassador to ASEAN were offset by much larger Chinese aid pledges to the region and the absence of a US proposal to compete with the China-ASEAN Trade agreement and the China-backed and ASEAN-led Regional Cooperation Economic Partnership (RCEP). Chinese commentary of the summit noted that ASEAN leaders tried to avoid alignment with the United States, notably by resisting US efforts to get them to support Washington in criticizing Russia in Ukraine.

Biden Visits Korea, Japan: Quad Summit, Economic Framework May 20-24

Heightened Chinese concern over US advances in Southeast Asia showed in critical Chinese media and commentary by the foreign minister and ministry spokespersons targeting the Quad summit (of Australia, India, Japan, and the United States) and the announcement of the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF). The latter agreement included seven of the 10 ASEAN members, along with the Quad powers, South Korea, and New Zealand.

Widely seen as targeting China’s expansionism and bullying, the Quad summit supported “a rules-based order,” affirmed that disputes should be settled without the threat of force, opposed attempts to unilaterally change the regional status quo and stated that the regional order should be free from all forms of coercion. The four powers advocated the Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy, long criticized by China. China sharply attacked the Quad meeting, with Foreign Minister Wang Yi advising on May 22 that the US-backed Indo-Pacific Strategy is causing more concern in the region and “is bound to fail.”

Figure 1 Chinese fishing fleet operating in North Korean waters. Photo: The Outlaw Ocean Project via CBC News

One result of the Quad meeting of particular concern to China was the Indo-Pacific Partnership for Maritime Domain Awareness (IPMDA). This effort was seen as likely to be carried out expeditiously with existing US and partner capacities and targeted at China’s use of fishing boats for illegal fishing— (China accounts for the bulk of illegal fishing in the Indo-Pacific, a source of major friction with most of its maritime neighbors and many Pacific Island nations).

The IPEF was viewed with greater Chinese concern. Chinese rhetoric depicted the pact as designed to “box in China” by restricting its regional “sphere of economic influence.” Official Chinese media cited expert opinion that the US-proposed IPEF is really a trade defensive measure involving export controls, import screening, secure supply chains, and other defensive measures targeting China. In response, Wang Yi announced Beijing’s plan to advance China’s accession to the other major Indo-Pacific trade agreement, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, as well as advance accession to the Digital Economic Partnership Agreement.

Shangri-La Dialogue: New Emphasis on Taiwan, US “Confrontational” Indo-Pacific Strategy, June 2022

Defense Minister Wei Fenghe’s speech at the Shangri-La Dialogue on June 12 gave a robust defense of China’s position on the Taiwan issue, while supporting Chinese commentary took aim at US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin’s speech critical of China’s aggressive policy and provocative behavior regarding Taiwan and other regional disputes. Chinese media repeated indictments of the US Indo-Pacific Strategy that was now depicted as facing China with constant political intimidation, economic coercion, and harassment by the US and “the cliques” of countries it supports. The Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson on June 13 strongly attacked US policy on the Taiwan issue and what was seen as its “militarization” in the Indo-Pacific region, viewing both as major threats to regional peace.

Figure 2 Chinese State Councilor and Defense Minister General Wei Fenghe delivers a speech on “China’s Vision for Regional Order” at the19th Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore on June 12, 2022. Photo: Li Xiaowei/Ministry of National Defense of the People’s Republic of China

G7 Summit, June 26; NATO Summit, June 30

Chinese commentary about the G7 summit focused on the announcement of the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) as a vehicle for geopolitical competition to counter China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The PGII pledged to raise $600 billion in private and public funds over five years to finance infrastructure in developing countries. Though casting doubt on the viability of PGII, Chinese media viewed this challenge more seriously than an earlier failed Biden-supported Build Back Better World infrastructure initiative in 2021. In particular, the PGII was seen as part of the negative turn against China by NATO, the European Union, and Europe’s major powers.

Chinese coverage of the NATO summit on June 30 concluded with the judgment that NATO was focused not just on Russia and Ukraine but also on an eastward expansion designed to contain China’s development. The commentary highlighted the participation of Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand in supporting the shift of the alliance now directed against China. A China Daily commentary on July 6 listed US gains in competing with China and judged that America’s “biggest gain” is “the new-found transatlantic unity that has consolidated its grip on NATO.”

Wang Yi Regional Tour, G20 Meetings: Solidify Relations, Challenge the United States

In a trip widely seen as directly challenging the United States, China’s foreign minister visited Myanmar, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Malaysia July 4-14. During the trip, Wang attended the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation Foreign Ministers Meeting in Bagan, Myanmar, a controversial visit that signaled the legitimation of the military junta and possibly undercut ASEAN’s efforts to incentivize change in the junta’s behavior. Wang gave speeches at the G20 Foreign Ministers meeting on July 7-8, met many regional counterparts at the G20 meeting, held a five-hour session with US Secretary of State Antony Blinken on July 9, and offered an assessment of US policy on Taiwan, Southeast Asia, and related issues at ASEAN headquarters in Jakarta on July 11. Wang’s rhetoric at the G20 sessions was moderate in dealing with the United States but his later comments at the ASEAN Headquarters were sharply critical. There, Wang warned against the United States “playing the Taiwan card” to disrupt and contain China. He alerted Southeast Asian countries about being used as chess pieces by the United States as they faced US coercion and bullying.

Chinese treatment of the session with Blinken implicitly rebuked US policy by disclosing the Chinese envoy gave Blinken four lists of Chinese requirements for the United States to follow to correct “mistakes” in its policies toward China and advance cooperation. At the ASEAN headquarters meeting, Wang went further in disclosing a thinly disguised reprimand of US policy. He said that he told the US leader to join China to “jointly uphold open regionalism…support ASEAN centrality, uphold the existing regional cooperation framework, and respect each other’s legitimate interest in the Indo-Pacific instead of aiming to antagonize or contain the other side.” He added that “If China and the US can have sound interaction in the Indo-Pacific, it could help release positive energy and also meet the expectations of all regional countries.” Wang concluded that “we look forward to the feedback of the US side to the Chinese proposal,” adding that the Chinese offer was a “test” of whether the United States can rise above its “hegemonic mentality” and “zero-sum logic” and play a constructive role in the region.

Subsequent harsh Chinese criticism of the United States left little doubt that Beijing had no expectation of a positive response to its tendentious offer. Brief public remarks by US Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Mark Milley at a meeting of Indo-Pacific military leaders in Australia in late July prompted strident Chinese commentaries warning that the US Indo-Pacific strategy was a recipe for “regional disaster.”

Threats over Taiwan Mar ASEAN Foreign Minister Meetings, August 3-5

As discussed in detail in the US-China relations chapter and other parts of this Comparative Connections, it became clear in July that Speaker of the US House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi was determined to stop in Taiwan with her congressional delegation during an Asian trip that had been postponed because of illness. Chinese ministry officials and official media warned in no uncertain terms of major consequences for this violation of China’s sovereignty. The visit took place on Aug. 2 as Chinese warnings reached a high point. Then there were more than four days of unprecedented Chinese shows of force surrounding Taiwan with naval and air power in maneuvers demonstrating an ability to blockade the island, along with ballistic missile firings, with some crossing over the island and some landing in Japan’s exclusive economic zone.

Wang Yi’s participation at the ASEAN Regional Forum and other ASEAN led foreign ministry meetings in Phnom Penh during Aug. 3-5 focused on the Taiwan crisis, which dominated the discussions. The Chinese foreign minister—supported by other Chinese officials and official media—was forthright in asserting China’s justification for its reaction to the Pelosi visit. They condemned US complaints that China was overreacting, a G7 statement supporting the US position, and a statement by the United States, Japan, and Australia calling on China to stop military demonstrations around Taiwan. The Chinese Foreign Ministry summoned diplomatic envoys from G7 countries and the European Union to protest the G7 statement. Wang canceled a scheduled meeting with the Japanese foreign minister and walked out of an ASEAN meeting during the Japanese foreign minister’s speech in protest over his criticism of China’s military provocations. Wang had no scheduled meeting with Secretary Blinken.

Wang pressed regional countries to support China’s position, joining broad Chinese efforts to muster support against the United States. Chinese spokespersons and official media repeatedly exaggerated the support China was receiving. In Southeast Asia, most governments avoided condemning the United States as they and an official ASEAN statement on the crisis reaffirmed their various “one-China” policies and stressed the need to restore calm. Without referring to either the United States or China, the ASEAN statement called for “maximum restraint” and urged all sides engaged in the intensifying conflict to “refrain from provocative action.” While not explicitly calling out Beijing for engaging in disruptive live-fire military exercises, the statement added that there is an urgent need to “uphold multilateralism” and to use all existing channels of diplomacy and dialogue to de-escalate tension.

Beijing repeatedly emphasized that the United States caused the crisis. There was little recognition in Chinese commentary during the ASEAN meetings that China’s actions in the crisis challenged its image as regional stabilizer and distracted attention from China’s positive contributions to the region through policies and actions in line with Xi Jinping’s various initiatives.

Chinese commentary after the military shows of force ended endeavored to show some empathy with regional countries concerned about China’s use of military force and the future of US-China relations. Official Chinese media on Aug. 9 disclosed that Wang Yi had assured his hosts during the ASEAN meetings and other stops in Southeast Asia that “Beijing is making every effort to preserve regional peace and stability. So while inflicting pain on the violators, Beijing has also shown that it wants to neither upend the China-US relationship nor disrupt the regional security landscape.”

An editorial in China Daily on Aug. 12 tried to reassure Southeast Asian countries that were surprised and “caught unawareness” by the “unprecedented” largescale PLA exercises targeting Taiwan. It acknowledged that these countries remained “reluctant to take sides” between the United States and China on the Taiwan crisis, as stability in US-China relations is important for regional stability and development. More broadly, it advised that “The whole world knows how important China-US relations are for the peace and development of the world economy and for the concerted efforts of the international community to tackle common challenges humanity faces.” It added, “And the whole world knows that China has tried hard to mend its relations with the US.”

Economic Progress, South China Sea Disputes

Beijing continued offering the usual positive outlook on China-ASEAN economic relations. ASEAN was highlighted as China’s largest trading partner, with reports in August forecasting double-digit growth for the year as China-ASEAN trade grew by 13% in the first seven months of 2022. The RCEP was depicted as an important impetus for the increasing trade. Meanwhile, China’s Global Development Initiative was repeatedly cited as providing guidance for China-ASEAN cooperation seeking solutions to development challenges.

In the South China Sea, China continued unilateral and coercive practices seeking its interests at the expense of other claimants. China again announced in May the annual three-and-a-half month ban on fishing in Chinese-claimed South China Sea waters disputed by other claimants. The Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) reported on May 26 three separate incidents over the previous two months where Chinese law enforcement vessels challenged marine research and hydrocarbon exploration carried out by Philippine vessels in the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone in the South China Sea. AMTI on July 27 showed Chinese Coast Guard ships in June blocking Philippine supply ships seeking to reach the Philippine outpost at Second Thomas Shoal. On June 17, Secretary of State Blinken issued a statement criticizing China coercion against the Philippines in the South China Sea. Blinken’s statement in July on the anniversary of the International Law of the Sea Tribunal 2016 ruling that rejected China’s South China Sea claims and supported the Philippines and other claimants was strongly rebuked by the Chinese Foreign Ministry.

On June 7, the Australian government made public a complaint about a Chinese fighter aircraft that on May 26 intercepted an Australian aircraft carrying out “routine surveillance activity in international airspace in the South China Sea region.” It disclosed that the Chinese plane’s dangerous maneuvers including releasing a bundle of chaff to foul the surveillance plane’s engines, which it said threatened the safety of the Australian plane and its crew. The Australian prime minister publicly denounced the Chinese action. Concurrently, Canada’s prime minister condemned Chinese fighter aircraft harassing in “irresponsible and provocative” ways Canadian surveillance aircraft operating in the Pacific in support of UN sanctions against North Korea. Chinese spokespersons rebutted the charges, accusing the Australian plane of intruding into China’s airspace over the Paracel Islands and ignoring Chinese warnings.

Figure 3 Wang Yi delivers remarks via video for the 20th anniversary of the China-ASEAN Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea. Photo: Xinhua

On June 28, China condemned the US “militarization of the Pacific” in the massive 26-nation, 25,000 personnel RIMPAC exercises running from June 29 to Aug. 4 as a US-led effort contain China and sow discord between China and its neighbors. The US Ronald Reagan Carrier Strike Group exercised in the South China Sea in July. One of the Group’s destroyers carried out freedom of navigation operations against Chinese holdings in the Spratly Islands and the Paracel Islands and then transited the Taiwan Strait. The actions were duly criticized by China. Significantly, after RIMPACended, the Ronald Reagan Strike Group remained in the Philippines Sea to the east of Taiwan during China’s unprecedented shows of force targeting Taiwan in early August. The strike group was joined by two US big deck amphibious ships armed with F-35B jet fighters.

Meanwhile, Wang Yi used remarks on July 25 marking the 20th anniversary of the China-ASEAN Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea to warn against outside interference and to urge forward movement in the protracted talks on reaching a code of conduct in the South China Sea.

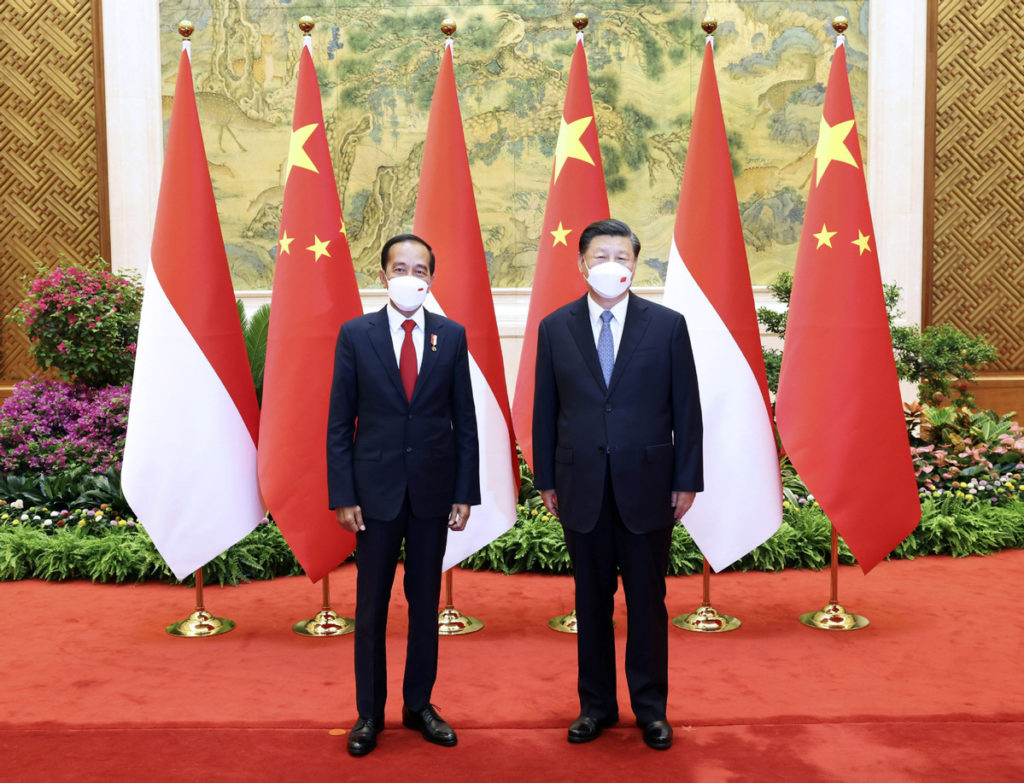

China-Indonesia: Widodo Visits China

President Joko Widodo visited China on July 25-26, the Indonesian leader’s fifth trip to the country. He was the first foreign head of state to visit Beijing since the Winter Olympics in February. Xi Jinping and supporting Chinese commentary emphasized close cooperation between the two countries under the rubric of the Belt and Road Initiative, and they highlighted several Chinese-supported infrastructure projects in the country, notably the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway. Indonesia was a focal point of Chinese supported vaccine production. Xi told Widodo that China provided Indonesia with 290 million does of COVID vaccines, more than any other country. Total China-Indonesian trade reached $66 billion for the first half of 2022, an increase of 28% from the same period in 2021.

Figure 4 Chinese President Xi Jinping holds talks with visiting Indonesian President Joko Widodo at the Diaoyutai State Guesthouse in Beijing on July 26, 2022. Photo: Xinhua

Xi highlighted Widodo’s international importance, pledged China’s support to Indonesia in hosting the G20 summit in November and welcomed Indonesia becoming the chair of ASEAN in 2023. Widodo accepted China’s offer to assist in the development of Indonesia’s new capital and in building an ambitious industrial park in North Kalimantan Province.

Chinese media acknowledged Chinese competition with the United States in noting that Indonesia was one of the ASEAN countries to join the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework. They also noted Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Milley’s visit to Indonesia in July, where he warned of the “aggressive” Chinese military. “Super Garuda Shield,” the large-scale (5,000 personnel) US-Indonesia military exercise that also involved Australia and Japan among other countries, took place in Indonesia Aug. 1-14 coincident with the Chinese military deployments and operations threatening Taiwan. Foreign media asserted Chinese concern over the exercise, but specific Chinese actions or statements were absent.

China-Philippines: Emphasizing Positives amid Uncertainties

Xi Jinping was in the lead in welcoming incoming President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. with letters, messages, and a phone conversation forecasting positive relations. Vice President Wang Qishan led the Chinese delegation to the inauguration ceremony on June 30. Foreign Minister Wang Yi met Marcos during his July 5-6 stay in the Philippines, when Marcos was viewed very positively by Chinese media as “lifting” China ties.

Figure 5 Philippine President Ferdinand Romualdez Marcos meets with visiting Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi in Manila, the Philippines, on July 6, 2022. Photo: Xinhua

It isn’t clear how far China is prepared to go in supporting infrastructure construction in the country. Outgoing President Rodrigo Duterte was disappointed with Chinese follow through on pledges of large-scale assistance that never materialized. Richard Heydarian reported on July 19 that the Marcos government scrapped three major railway projects promised to Duterte because Beijing failed to provide promised financing. Heydarian and some foreign specialists anticipate Marcos will follow a more balanced approach to China and the United States than did Duterte, who had a strong bias against the US. They aver that Marcos has voiced a tougher stance than Duterte on South China Sea disputes with China, and that public opinion and the Philippines security and foreign policy bureaucracy are more distrustful of China than they were at the start of Duterte’s term six years ago. Other observers see Marcos more positively inclined toward China. On Aug. 22, China Daily reported in apparent reference to rail projects earlier reported ended by Marcos that “the Philippines has resumed negotiations with China on the funding of three railway projects.”

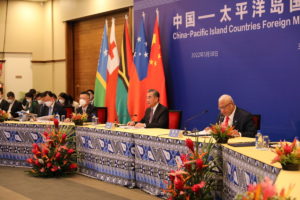

China-Pacific Islands: Advances and Set-backs

Chinese commentary strongly defended Beijing’s security agreement with the Solomon Islands against criticism from Australia, New Zealand, the United States and others concerned about its security forces gaining military access to the strategically located nation. That the secret agreement signed in April represented only part of China’s rapidly expanding ambitions in the Pacific Islands became clear when the president of the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) released a letter on May 20 along with copies of two documents China had sent to all Pacific Island states having diplomatic relations with China. The documents were for consideration and proposed adoption at the second China-Pacific Island Countries Foreign Ministers meeting on May 30. Others in the region released the documents to the media.

Figure 6 State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi meets with Solomon Islands’ Foreign Minister Jeremiah Manele in Honiara, capital of the Solomon Islands, on May 26, 2022. Photo: Xinhua

The FSM president, an advocate of good relations with China and an honored guest in Beijing, nonetheless came down hard against the Chinese plan. The proposed agreement would have allowed China to train local police, become involved in cybersecurity, expand political ties, conduct sensitive marine mapping, and gain greater access to natural resources on land and in the water. It was viewed as deceptive in hiding China’s ambitions to bring the Pacific Island states into China’s orbit and to control security, infrastructure, fisheries, and other assets in ways that would challenge the regional states and their traditional international supporters, notably Australia, Japan, New Zealand, and the United States. The latter were sure to resist, leading to great power confrontation with the Island countries losing control of their sovereignty and independence while suffering negative consequences in the middle of the struggle. Other regional leaders also voiced reservations about the rushed consideration and potentially wide-ranging implications of China’s proposed regional plan.

The China-Pacific Island States Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in Fiji was the highlight of Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s 10-day trip to seven Pacific Island countries and virtual meetings with officials of three other Pacific Island countries. The Pacific Island foreign ministers did not approve the Chinese plan. They did agree on cooperation with China on five areas including health, disaster management and agriculture. But Wang said more discussion was needed on the Chinese proposal.

Figure 7 State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi co-hosts the second China-Pacific Island Countries Foreign Ministers’ Meeting with Fijian Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Voreqe Bainimarama in Suva, Fiji on May 30, 2022. Photo: Xinhua

The Chinese foreign ministry quickly reacted to the setback with a Position Paper on Mutual Respect and Common Development with Pacific Island Countries, which offered 15 “visions and proposals” for deepening engagement with the region. Notably, the paper focused largely on political and economic issues, with only brief mention of the security issues that had sparked the most controversy.

Chinese media offered a positive assessment of Wang’s trip where he met with 17 “leaders,” and more than 30 ministers of all 10 Pacific Island states having relations with China. In an interview on June 5, Wang said China had no intention of competing for influence or engaging in geopolitical competition. He supported the longstanding triparty—Australia, New Zealand, Pacific Island states—cooperation and said China was open to joining as a fourth party in this endeavour.

Chinese media said all 10 Pacific Island nations have signed Belt and Road cooperation documents with Beijing and all expressed readiness to join China’s Global Development Initiative. Wang signed several bilateral agreements at each of his stops, with some reportedly having the potential to cause controversy, as in the case of the April China-Solomon Islands agreement. China’s trade with the region was valued at $5.3 billion in 2021. Up to now, Beijing has implemented over 100 aid projects in the region, delivered more than 200 batches of in-kind assistance, and trained 10,000 people in various fields. China has provided the countries with about 600,000 doses of COVID vaccine.

Other Chinese media and the Foreign Ministry spokesman criticized the United States and its partners seen seeking to counter Chinese advances in the Pacific Islands. Special criticism focused on the US-New Zealand agreement between President Biden and Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern that focused on challenges posed by China but particularly in the Pacific Islands. Beijing also denounced the late June announcement of an alliance of Australia, Japan, New Zealand, United Kingdom, and the United States to boost economic and security ties with Pacific Island states.

After the conclusion of Wang’s trip, Chinese coverage of Pacific Island matters became infrequent and low key, focusing on development projects in the region, notably the China Pacific Island Countries Poverty Alleviation and Cooperation Development Center established in Fujian Province in July. Global Times criticized reported US and Australian government concern with the Solomon Islands’ institution in late August of a moratorium on foreign military ships visiting the country, pending a review of policy and procedures. The moratorium followed the Solomon Islands government’s prolonged non-response to separate requests by a US Coast Guard ship and a British Navy ship to visit the country to refuel and resupply.

Outlook

It remains to be seen whether and how China will try to reduce regional anxiety over its use of force targeting Taiwan, the United States, and US allies. The impact of the Taiwan crisis on the Chinese image and influence in competition with the United States remains uncertain. More definite is the most important development in Chinese foreign relations in several years: Xi Jinping is slated to resume travelling abroad after almost three years of COVID restrictions. Xi is widely anticipated to become an even more powerful leader after the Chinese Communist Party Congress to be held in October. The attention he will show to Southeast Asia among many Chinese foreign policy priorities will send important signals to regional states and foreign competitors. Xi routinely attends the annual APEC leaders meeting which is set for November 2022 in Thailand, and is expected to attend the G20 summit in Indonesia shortly thereafter where a possible meeting on the sidelines with Joe Biden will be highly anticipated.

May 12-13, 2022: US President Joe Biden hosts the leaders of Southeast Asia in Washington, DC. The US-Southeast Asia summit focuses on cooperation, including regional trade, human rights, and climate change. The summit seeks to counter China’s increasing influence in Asia, with the White House announced new investments of about $150 million in its partnership with Southeast Asia, and the deployment of additional maritime assets, led by US Coast Guard, to help enforce maritime laws in the region.

May 26, 2022: Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative reports three separate incidents in the last two months in which Chinese law enforcement vessels challenge Philippine marine research and hydrocarbon exploration ships in the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone.

June 8, 2022: Chinese embassy in Cambodia confirms that Beijing has provided aid for the renovation project for Cambodia’s Ream Naval Base. China maintains that its military will boost bilateral cooperation as it helps modernize and build the capacity of Cambodia’s navy. The Cambodian government reiterates that it does not allow foreign military bases in the country, countering reports that China is developing the naval base for the People’s Liberation Army Navy’s use.

July 1, 2022: Pew Research Center releases new global public opinion poll showing that concerns about China’s human rights record has grown, with increasing unfavorable views of China among survey respondents in North America and Europe.

July 4-6, 2022: Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi arrives in Myanmar and becomes the highest-ranking Chinese official to visit the country since the coup in February 2021. Wang meets with foreign ministers from the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation Group in Bagan, Myanmar. In the meeting, Wang pledges that China will share more data on the Mekong River with the group amid growing concerns and criticisms that China’s activities upstream are causing flooding and drought in downstream countries and affecting nearly 70 million people in the lower basin of the Mekong River.

July 6, 2022: FM Wang Yi visits Thailand and meets with Thai counterpart Don Pramwudwinai. They exchange views on regional security and agree to deepen bilateral economic ties. This year marks the 10th anniversary of the Comprehensive Strategic Cooperative Partnership between Thailand and China.

July 6, 2022: FM Wang Yi continues his Southeast Asia tour and meets senior leaders in the Philippines, including President Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. They discuss bilateral political, security, and economic relations.

July 15, 2022: China and Vietnam agree to speed up establishment of a hotline to respond to marine fisheries incidents and to cooperate in search and rescue missions at sea.

July 25, 2022: Chinese President Xi Jinping meets visiting Indonesian counterpart Joko Widodo in Beijing. They pledge to deepen bilateral ties through China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Indonesia’s Global Maritime Fulcrum. Widodo personally extends an invitation to Xi to attend November’s G20 summit in Bali, Indonesia.

Aug. 4, 2022: FM Wang Yi visits Cambodia and meets ASEAN foreign ministers. In a multilateral meeting with regional diplomats, Wang maintains that China will continue to invest in and promote regional development for ASEAN countries.

Aug. 4, 2022: ASEAN issues a statement following meeting of the group’s regional foreign ministers in Phnom Penh. It calls for “maximum restraint” in the Taiwan Strait, urging against any “provocative action” following US Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan. The statement is released as China announces the start of a four-day, live-fire drill around Taiwan.

Aug. 13, 2022: Chinese Defense Ministry announces that it is sending fighter jets and bombers to Thailand for a joint exercise with the Royal Thai Armed Forces. The exercise will include training for air support, strikes on ground targets, and troop deployment.