Articles

Over the summer three Southeast Asian nations—Thailand, Cambodia, and Indonesia—conducted political contests or prepared for them, with Washington and Beijing watching closely for shifts in alignments or opportunities to make inroads with new leaders. Despite this, and possibly because of it, China made bold moves in the South China Sea and caused outcry in the region with the release of a map supporting its claims to the “Nine-Dash Line.” Beijing also showed signs of worry about Russian inroads into Southeast Asia and the Indo-Pacific region. The high-profile visit to Washington of Philippine President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, Jr. enabled both countries to reconfirm the US-Philippines alliance publicly, although it gave little indication of where the broader relationship may be headed. ASEAN continued to make little headway in helping to resolve the conflict in Myanmar; and the 2023 chair, Jakarta attempted to redirect the group toward economic goals and a common approach to looming food insecurity in the region.

However, Jakarta may be set to swim in deeper waters: Indonesia was among 20 countries invited to join the BRICS group of “middle powers,” and the only one from Southeast Asia. Jakarta deferred membership for two years in order to “consult” with regional leaders, leaving the new president to make a decision on entering the BRICS, but Indonesia is not likely to turn down the opportunity to play a greater role on the world stage.

Marcos Goes to Washington

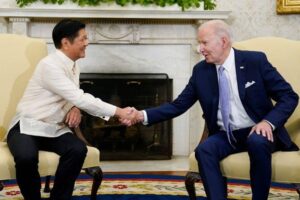

Philippines President Marcos’ official visit to the United States in the first week of May signaled the normalization of relations between Washington and the Marcos dynasty—an optic of greater benefit to Marcos—and solidification of the agreement in February to add four basing sites to the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA), thus expanding US “flexible basing” in the South China Sea.

At the top of the Biden administration’s list of topics for the visit was “modernization” of the US-Philippines alliance, the culmination of which was the release during Marcos’ visit of the first-ever Philippines Basic Defense Guidelines. The Guidelines clarified language in the bilateral Mutual Defense Treaty to specify that the United States would defend the Philippines if its official vessels were attacked in the South China Sea, although the defense of Filipino fishing vessels was presumed to be left to the Philippine Coast Guard, which Washington also pledged to strengthen. An underlying objective of the guidelines is to achieve greater inter-operability between the US and Philippine armed forces, with significant assistance from Washington, although asymmetry between the two militaries could make that an uphill battle.

Although welcoming the Guidelines and the overall expansion of the alliance, Manila expressed some reservations:

- First was a longstanding concern that the Mutual Defense Treaty applies to attacks on official Philippine vessels and not on fishing or other private vessels. Defense of the Philippine fishing fleet will be handled through US support to strengthen the Philippine Coast Guard, but Washington will not have formal responsibility under the current MDT.

- Second, the addition of new EDCA sites will expand the US military presence in the Philippines. The local population around sites facing the Taiwan Strait have expressed concern that they will become targets of Chinese aggression. An increased US presence also revives longstanding demands from Manila that US troops come under the jurisdiction of host country courts, as they do in Japan and South Korea; however, Washington held firm on its refusal to agree to forfeit jurisdiction over US soldiers in the Philippines.

- Third, Manila fears that promises of long-term security assistance to strengthen inter-operability between the two militaries could fail to materialize if the 2024 elections put an “America First” president in office who downplays the value of alliances in US foreign policy.

Manila likely envisioned a broader agenda. In the days leading up to Marcos’ arrival in Washington, the Philippines issued a press release describing the agenda for the two presidents as purely economic. Throughout his visit, Marcos made public statements to the effect that “the real security is economic security,” avoiding mention of geopolitical security whenever he could. Any significant movement in US-Philippine economic relations is likely to be in the announcement of the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), loosely scheduled for the end of 2023. Marcos did secure one small gain through his trip: Biden promised to dispatch a Presidential Trade and Investment Mission to the Philippines.

One item on Manila’s agenda for the visit of the US investment delegation will be the Maharlika Investment Fund (MIF), the Philippines’ first sovereign wealth fund. Signed into law by Marcos on July 18, the MIF is intended to be the flagship initiative for the administration’s goals of strengthening Philippine infrastructure and lifting a greater proportion of the population into the middle class. The government will provide a nest egg of just over $3 billion and hopes to attract multiples of that from foreign investors, both private sector and government. The MIF has drawn criticism for its potential to encourage corruption—opponents point to the 1MDB scandal in Malaysia—but Marcos insists that guardrails have been written into the MIF charter. For funding, he has modeled the MIF on Indonesia’s sovereign wealth fund, the Indonesian Investment Authority (INA) established in 2021, which Jakarta reports has garnered $20 billion in pledges. The US Development Finance Corporation (DFC) is one contributor to the INA’s nest egg, and Manila will press Washington to follow suit for the MIF.

Political Contests and Currents

During the Cold War era, one-man rule was common in Southeast Asia and superpower rivals sought to build client states in the region by competing for the allegiance of individual leaders. Although personalities still weigh heavily in Southeast Asian politics, they are often less important than political systems, imbedded interest groups and political dynasties. Nevertheless, in the aftermath of political transitions or the lead-up to them, major powers still seek to make early inroads with new leaders. This competition is a key feature in US-China rivalry in Southeast Asia, and political contests in 2023, and into 2024, offer several opportunities.

Figure 1 US President Joe Biden shakes hands with Philippines President Ferdinand Marcos Jr as they meet in the Oval Office of the White House in Washington, DC, on May 1, 2023 [Carolyn Kaster/AP Photo]

From elections on May 14 to the inauguration of Prime Minister Srettha Tavisin on Aug. 22, the political maneuvering that drove the Move Forward Party, the pro-democracy party that won the most votes, out of the ruling coalition and put the Pheu Thai Party (PTP), the second-largest vote-getter, at the helm of the new administration was predictable. Pheu Thai, the political base for the family of former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, brought the two parties most closely aligned with the military, Phalang Pracharat and Thai Union, into the coalition. This all but assured that the military-dominated Senate would approve Srettha’s nomination as prime minister.

On Aug. 22, as Srettha was inaugurated, Thaksin returned to Thailand after two decades in exile and was transferred from the airport to the Bangkok Central Prison, to begin serving an eight-year sentence on three criminal charges. On Aug. 28 King Maha Vajiralongkorn granted Thaksin a royal pardon and reduced his sentence to one year; he is unlikely to be required to serve out the full year.

Although Move Forward’s robust political base, which is dominated by younger generation Thais, has publicly expressed disappointment and disapproval of this series of political sleight-of-hand tricks, the coalition led by Pheu Thai promises some stability. Apart from bringing the military into the tent, Pheu Thai populist policies have traditionally been very popular. Srettha has promised to raise the minimum wage; give each Thai a small payment through a “digital wallet”; and raise agricultural prices. Although Pheu Thai is now more of a fixture of the Thai political establishment than it was in the first decade of the century, when its “Red Shirt” adherents fought an urban war against “Yellow Shirt” conservatives, it could still fall afoul of the military if it is viewed as accruing too much power. That is unlikely in the near-term–it must manage an 11-party coalition—but Thaksin’s rehabilitation will need to be managed carefully.

The change of leadership from former Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha, co-leader of the 2014 coup against Yingluck Shinawatra, to Srettha raises questions of shifts in Thailand’s foreign policies. In recent months Prayuth had raised hackles ASEAN and the West for setting up direct dialogue with the junta in Myanmar. Pheu Thai will attempt to be more inclusive and draw in the National Unity Government, but it will also represent Thai economic interests in Myanmar. Thailand is Southeast Asia’s top trading partner with Myanmar at present, primarily in energy.

Of equal, if not greater, interest will be Thailand’s relations with the United States and with China. Washington and Bangkok have attempted a reboot of the US-Thailand alliance, but it lacks the centrality of the alliance with the Philippines because Thailand is not a claimant in the South China Sea. At the same time, Chinese tourism in Thailand is an important component in recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. More important, Beijing is pressing Bangkok to move forward on its most important BRI project in Thailand, a high-speed rail link from northern Thailand to Bangkok, which would complete the rail line from Kunming to Bangkok.

Thailand’s trade with China was a critical element in the country’s double-digit growth in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when Thaksin entered politics and Pheu Thai, whose leadership is comprised of self-made billionaires, will look for opportunities to expand economic relations with Beijing. At the same time, Srettha has signaled that he intends strengthen relations with Washington: he will participate in a US-Thailand security meeting with Defense Minister Sutin Klungsang when he visits New York in September for the opening of the UN General Assembly.

Cambodia

Figure 2 Hun Manet, Cambodia’s new prime minister, right, shakes hands with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi during a meeting at the Peace Palace in Phnom Penh, Cambodia on Sunday, Aug. 13, 2023. Photo: EPA-EFE

The inauguration of former Army Commander Hun Manet, eldest son of Hun Sen, in Cambodia on Aug. 22 will likely spark more intense competition for political influence between Washington and Beijing than the contest in Thailand. Hun Manet’s ties to the West are far deeper than those of his father: he is a graduate of West Point and also holds an MBA (from the US) and a PhD in economics (from the UK). Western hopes that Hun Manet will be more democratic are probably overblown; whether he will seek a foreign policy that is better balanced between China and the United States is a more open question.

Nor is it clear whether the move from Hun Sen to Hun Manet represents a genuine transition of power. Hun Sen will remain as leader of the Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) and in early 2024 will assume the role as president of the Senate. The latter will entitle him to step in as head-of-state if King Sihamoni is unable to serve. More to the point, he has said publicly that he would take back the position of prime minister if his son “fails to meet expectations.”

It is more certain that the transition represents a generational shift within the CPP. However this shift will, if anything, strengthen the family-based dynasties that make up the party. Of the 30 Cabinet slots expected to be finalized in the early fall (the candidates for which were chosen by Hun Sen, not by Manet), 13 are expected to go to the sons and daughters of high-ranking CPP officials. Most significantly, Tea Seiha will succeed his father Tea Banh as defense minister, and Sar Sokha will replace his father Sar Kheng as interior minister. Hun Sen’s youngest son, Hun Many, will be minister of civil service.

That said, the new Cabinet will be more technocratic than previous ones: eight ministers are technocrat holdovers, and four new ones will join their ranks. Most notably, Sok Chenda Sophea, a French-trained economist who recently served as secretary-general of the Council for Development, which vets all foreign investment, will be foreign minister and a deputy prime minister.

China’s eagerness to make an early bid for influence over the new leader in Phnom Penh was obvious when Foreign Minister Wang Yi visited to meet Hun Manet prior to his inauguration. Washington has not made such overt overtures, but the administration’s response to the election on July 23 was muted. It criticized the July 23 election, in which the CPP had no real competition because Hun Sen had hollowed out the opposition with criminal charges and other measures and held out the possibility of imposing sanctions on a few unnamed individuals. However, there is little enthusiasm in the West for significant tightening of sanctions at this point.

Although many Western observers place Cambodia squarely in China’s camp, the issue is more complicated. China is Cambodia’s largest foreign investor, but the United States is its largest export market. Compared to other mainland Southeast Asian countries, including Thailand, Phnom Penh has been more outspoken in opposing the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

An early indicator for Washington will be Hun Manet’s handling of the Chinese presence at Ream Naval Base. Both Beijing and Phnom Penh continue to insist that China will not have exclusive rights to the base, but there are many arrangements short of permanent basing that might be extended. US-Cambodian military-to-military relations are constrained, if not completely obstructed, at this time but Hun Manet has often said that he favors restarting a military dialogue. For Washington, this may be an appealing first step in relations with the new leader.

Indonesia

Although the official campaign season for the February 2024 presidential elections in Indonesia will not open until later this year, public opinion surveys show two candidates in the lead: Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto and West Java Governor Ganjar Pranowo, nominee for of the powerful PDI-P led by former president Megawati Sukarnopoutri. The two are running neck-and-neck in the polls and may continue to do so up to the election. Current president Joko Widodo is ineligible for re-election of because of term limits.

Of the two candidates, Prabowo has more experience in foreign policy, although he has also attracted criticism on that score. A former military leader, in the 1990s Prabowo was accused of human-rights violations when he was a member of KOPASSAS, the military’s special forces and was periodically placed on visa blacklists by the State Department. More recently, a proposal that Probowo made to resolve the conflict in Ukraine at the Shangri-La Dialogue in June, with terms that would potentially favor Russia, was met with public disbelief and criticism, including from Joko.

In broad terms, there may not be dramatic differences between Indonesian foreign policy under Prabowo and under Ganjar. Indonesian leaders all show deference to Jakarta’s deep vein of non-alignment and to ASEAN centrality. That said, both Prabowo and Ganjar have made pro-China statements in recent months. In his capacity as defense minister, Prabowo has advocated stronger military-to-military relations with Beijing. He has also called for greater economic “self-reliance” for Indonesia; this more cryptic statement likely refers to balancing trade and investment between China and the West. Ganjar has not made specific proposals for his foreign policy as yet, but has included China-friendly rhetoric in his broad statements.

In the run-up to the elections, Washington will make use of the channel between Defense departments to promote dialogue with Prabowo. He and Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin met on the margins of the Shangri-la Dialogue. In August, the two officials issued a joint statement, declaring that the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific (which was issued in response to the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue) and the US Indo-Pacific Strategy have common fundamental principles and that Chinese maritime claims in the South China Sea are “inconsistent with international law.” The purpose of this statement was likely two-fold. It helped to assuage Southeast Asian objections that Austin’s speech at Shangri-la made little mention of ASEAN, and it put Prabowo on the record expressing concern over Chinese behavior in the South China Sea.

Beijing Rumbles in The Region

As Southeast Asian leaders attempt to navigate a path between China and the United States, Beijing has made that more difficult in recent months with hostile maneuvers in the South China Sea. Incursions into the EEZs of Southeast Asian countries are often cyclical for the Chinese Coast Guard and its maritime militia. Incidents to intimidate Southeast Asian private vessels often occur in the springtime, the high season for fishing in the Spratlys. Oil and gas exploration in the South China Sea typically takes place in the summer, and China attempts to obstruct Southeast Asian operations that are often joint projects with other regional powers. For the past several years there has been a strong pattern of such intimidation in Vietnamese waters, to disrupt joint exploration between Vietnam and Russia. However, just as many if not more incidents are intended to make a political statement—aimed at external powers as well as Southeast Asian governments—or have no apparent reason other than a display of force.

Figure 3 Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III greets Indonesian Minister of Defense Prabowo Subianto at the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) 20th Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore, on June 2, 2023. (DoD photo by Chad J. McNeeley)

On May 10 a flotilla of Chinese vessels entered the Vietnamese EEZ and loitered in a Russian-Vietnamese offshore lease block. A Chinese survey ship was noted by commercial satellites to be accompanied by two Chinese Coast Guard patrol vessels with at least seven maritime militia trawlers. The size of the flotilla was widely interpreted as an attempt to intimidate not only Vietnam but also Russia, whose presence in the Indo-Pacific appears to worry Beijing as the Ukraine war goes on. On Aug. 5 Chinese attempted to obstruct a Philippine resupply mission to Second Thomas Shoal. The US State Department issued an immediate statement of support for the Philippines. To crown these incidents, in late August the Chinese Ministry of Natural Resources issued a “standard” map of the Indo-Pacific which showed Chinese claims on most of the South China Sea, as well as disputed areas in Russia and India. The collective outcry was swift and uniform among Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam.

Figure 4 A China Coast Guard vessel patrols at the disputed Scarborough Shoal April 5, 2017. Picture taken April 5, 2017. Reuters/Erik De Castro/File

This trajectory adds both urgency and skepticism to longstanding ASEAN efforts to develop a Code of Conduct on the South China Sea with Beijing. On July 13, in a China-ASEAN post-ministerial meeting, the two sides agreed upon new guidelines for negotiation of a COC. Southeast Asian leaders place little faith in the COC process—or believe that China would necessarily follow a Code if one is negotiated—but pursue it to maintain a channel for dialogue with Beijing. Nevertheless, under Indonesia’s chairmanship this year ASEAN intends to strengthen its joint approach to the South China Sea: in June Jakarta announced that at the 10 member states would conduct their first-ever ASEAN joint military exercises in the South China Sea in September, in the North Natuna Sea.

Indonesia’s Expanding Role

ASEAN’s continued lack of success in pushing the Five-Point Consensus Plan for Myanmar has led to inevitable speculation on whether the regional group is losing traction. This is partly in anticipation of the ASEAN chair’s rotation from Jakarta to Vientiane in 2024. However, although Laos lacks the resources to conduct a robust chairmanship, Vientiane generally allows itself to be guided by the larger members. That said, there is no reason to believe that ASEAN can play a pivotal role in resolving the conflict in Myanmar in the near-term.

As a result, Jakarta has focused the ASEAN agenda on other issues. Of particular urgency this year is the possibility of a two-pronged food crisis in the region, due to Russian threats to blockade Ukrainian shipment of grain out of ports in the Black Sea, which will have particular impact on Southeast Asia’s wheat imports, and the El Nino cycle, which will have a negative impact on Southeast Asian rice harvests this year and the next. As the world’s largest wheat importer, Indonesia will experience severe shortages of the grain unless Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan can persuade Vladimir Putin to reverse course.

Figure 5 The participating countries of the East Asia Summit (EAS) met on 7 September 2023 in Jakarta, Indonesia, under Indonesia’s 2023 ASEAN Chairmanship on the occasion of the 18th East Asia Summit. Photo: Association of Southeast Asian Nations

In reality, there is little that ASEAN can do to avert either situation, but Jakarta is focused on collective action that may cushion shocks in food prices. Joko has proposed a structure similar to that ASEAN adopted during the COVID-19 pandemic to set up intra-regional supply chains and create reserves of food supplies that may be particularly endangered during global shortages.

Although Indonesia is often viewed as the unofficial leader of ASEAN, Jakarta is also contemplating a larger role in global groups that offer space for “middle powers” to exercise leadership, particularly of the “Global South.” Indonesia received good marks for its chairmanship of the G20 in 2022, not least because it was forced to operate in an international environment electrified by the war in Ukraine. In August the BRICS group announced that it intended to add 20 new members over time; it issued immediate invitations to Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. Included in the group of 20 is Indonesia, the only Southeast Asian country to be considered for membership. Jakarta has requested that an invitation be deferred for two years, citing the need to conduct regional consultations. Those consultations will go beyond other ASEAN states and most importantly include Beijing, New Delhi, and Moscow.

Looking Ahead

The remaining months of 2023 will be an intense time for US diplomacy with Southeast Asia, all the more so because Washington will likely be distracted by US elections in 2024. President Biden’s planned trip Vietnam, where the two countries are expected to elevate the bilateral partnership, will raise the US profile in Southeast Asia. However his decision to skip the East Asia Summit in Indonesia will be viewed as lack of US support for ASEAN and a win for China by default.

The APEC meeting in San Francisco in November and the anticipated release of the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework in late 2023 will push Washington to reveal its economic agenda for the region. China’s maritime aggression has motivated some Southeast Asian states to strengthen security cooperation with the United States and its allies, but they still seek to balance with stronger economic relations with China—Marcos spoke for the region when he underscored the importance of economic security.

The fall months will also clarify the tone for US relations with Thailand, Cambodia, and Indonesia in the near-term. However, just as Washington will watch for signs of shifting alignments among Southeast Asia’s newly-elected or prospective leaders, Southeast Asians will look to US elections in 2024 with an eye to the possibilities for continuity or change.

May 1-5, 2023: Philippine President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, Jr., visits Washington, his first visit to the capital since his father was forced to leave office in 1986.

May 10, 2023: A flotilla of Chinese vessels enter Vietnamese waters and loiter in a Russia-Vietnam offshore lease block. A Chinese research vessel moves at a speed appropriate for surveying,

May 10-12, 2023: Indonesia hosts the first ASEAN Summit of the year in Labun Bajo. Myanmar is not represented.

May 14, 2023: Thai general elections are held, with a record turnout of 75.22%. The competing parties cover the political spectrum from the pro-democracy Move Forward Party to two parties —Thai Union and Phalang Pracharat—headed by the organizers of the 2014 coup.

June 2-4, 2023: 20th Asia Security Summit (Shangri-la Dialogue) is held in Singapore. US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin meets on the sidelines with counterparts from Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore.

June 8, 2023: In its capacity as ASEAN chair, Jakarta announces that the 10 ASEAN states will hold the first-ever ASEAN joint military exercises in the South China Sea in September. The exercises will not include combat operations training and will be held in the North Natuna Sea.

June 16, 2023: Singaporean Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan meets US Secretary of State Antony Blinken during his visit to Washington. They discuss US-China relations and US-Singapore environmental cooperation, including the Green Shipping Challenge which aims to reduce emissions in trade.

June 21, 2023: US Treasury Department announces new sanctions on Myanmar and designates two regime-controlled banks, Myanmar Foreign Trade Bank (MFTB) and Myanma Investment and Commercial Bank (MKN), both of which have been instrumental in facilitating the military’s use of foreign currency to procure arms and jet fuel abroad.

June 29, 2023: Vietnam Communist Party External Relations Chairman Le Hoai Trung visits Washington and meets Secretary of State Blinken.

July 13, 2023: On the margins of the ASEAN Foreign Ministers Meeting, China and ASEAN announced new guidelines for negotiation of a Code of Conduct in the South China Sea.

July 13-14, 2023: Secretary of State Blinken travels to Indonesia, where he participates in the ASEAN Foreign Ministers Meeting and the 30th ASEAN Regional Forum. While in Jakarta he and Indonesian Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi hold the second US-Indonesia Ministerial Dialogue, discussing supply chains, advancing energy transition, and bilateral cooperation on maritime security and defense.

July 18, 2023: Philippine President Bongbong Marcos signs into law legislation to create the Philippines’ first sovereign wealth fund, the Maharlika Investment Fund (MIF).

July 23, 2023: Following general elections in Cambodia in which the Cambodian People’s Party won 120 out of 125 seats, the US State Department said it had “taken steps” to impose visa restrictions “on individuals who undermined democracy and implemented a pause of foreign assistance programs” after determining the elections were “neither free nor fair.”

July 25, 2023: United States and Vietnam mark the 10th anniversary of the US-Vietnam Comprehensive Partnership, increasing speculation that the two countries will move to a Strategic Partnership in the near future.

July 31, 2023: State Administrative Council (SAC) on Myanmar extends the state of emergency for another six months. The first SOE was imposed in the February 2021 coup which overthrew the elected civilian government led by the National League for Democracy (NLD).

Aug. 4, 2023: Indonesian Coordinating Minister for Investment and Maritime Affairs Lahut Binsar Pandjaitan visits Washington and meets Secretary Blinken to discuss implementation of Indonesia’s Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) and the importance of critical minerals to clean energy.

Aug. 5, 2023: Chinese Coast Guard and maritime militia vessels use water cannons and other maneuvers to obstruct a Philippine resupply mission to Second Thomas Shoal. The US State Department issues an immediate statement of support for the Philippines.

Aug. 8, 2023: Secretary of Defense Austin and Philippines Secretary of National Defense Gilberto Teodoro, Jr., confer by telephone on recent events in the South China Sea.

Aug. 12, 2023: Malaysia holds six state elections, which are viewed as a contest of political strength between the government coalition (PH) led by Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim and the opposition coalition (BN), which includes the Islamist fundamentalist party PAS. As expected, the results are split evenly—each side won three states each—but the PH won their states with a smaller majority than it had previously held, with gains shown by PAS.

Aug. 17, 2023: United States and Philippines launch inaugural US-Philippines Energy Policy Dialogue, established during Vice President Kamala Harris’ trip to the Philippines in November 2022.

Aug. 22, 2023: After more than three months of political and judicial maneuvering, the Thai parliament approves nomination of the Pheu Thai Party’s Srettha Thavisin for prime minister. On the same day former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra returns to Thailand after a 15-year self-exile. As there are three criminal charges outstanding against him, Thaksin is taken from the airport to prison, where he is placed in a hospital ward. He faces eight years in detention.

Aug. 22, 2023: Cambodian legislature approves nomination of Hun Manet, eldest son of former prime minister Hun Sen, as prime minister, marking a generational shift in the dominant Cambodian People’s Party (CPP).

Aug. 23, 2023: US Treasury expands use of sanctions in Burma to impose penalties on any individual or entity operating in the jet fuel section of the Burmese economy, designating two individuals and three entities involved in procuring and distributing jet fuel to the Burmese military.

Aug. 24, 2023: Secretary of Defense Austin and Indonesian Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto issue a joint statement that the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific and the US Indo-Pacific Strategy hare fundamental principles and that Chinese maritime claims in the South China Sea are “inconsistent with international law.”

Aug. 24, 2023: BRICS Summit opens in South Africa with the announcement that six nations were invited to join the group. Indonesia, in the group of 20 countries on track to enter, announced that it would defer decision on entering for two years.

Aug. 28, 2023: China’s Ministry of Natural Resources issues a “standard” map of the Indo-Pacific region which reflects Chinese claims to most of the South China Sea as well as disputed areas in India and Russia. Malaysia, Vietnam, and the Philippines make public statements of protest over the map.

Aug. 31, 2023: Thai King Maha Vajiralongkorn pardons Thaksin and reduces his prison sentence to one year.