Articles

Australia has peeled back China trade coercion as it ramps-up the alliance with the United States to balance China. The Labor government, elected in May 2022, claims a diplomatic thaw with China as a key achievement. The major defense step was agreeing for Australia to get nuclear submarines under the AUKUS agreement with Britain and the United States. The government’s 2023 National Defense Statement describes “an intense contest of values” in the Indo-Pacific, with growing “risks of military escalation or miscalculation.” Because of the worsening strategic environment, the Australian Defense Force is judged “not fully fit for purpose” as the government seeks greater long-range strike capability. The era of alliance integration will see more US troops, planes, and ships in Australia, and the creation of a US-Australia combined intelligence center in Canberra. The contest with China in the South Pacific frames a new Australian aid policy and a greater US role in the islands.

End China’s trade pressure, stabilize the relationship

A stable relationship between Australia and China is in the interests of both countries and the broader region. Australia will continue to cooperate with China where we can, disagree where we must, manage our differences wisely, and, above all else, engage in and vigorously pursue our own national interest.

Australia’s 2023 National Defense Statement

“Stabilize” is the word of the year in the Labor government’s dealings with China (although, of course, Australia spells it “stabilise”). The stability effort had a threshold condition—Beijing must cease trade coercion. And Beijing is meeting this condition. The trade bans China imposed on Australia three years ago are being revoked, opening the chance for a Beijing visit by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese later this year. The pressure China applied to Australia failed. Canberra did not bow and Australia’s economy did not falter. The Economist judged “Australia has faced down China’s trade bans and emerged stronger,” while the Australian Financial Review boasted “China’s sanctions against Australia have been a spectacular failure.”

Canberra’s offense three years ago was to speak hard truth at the moment China’s leader, Xi Jinping, faced his greatest peril from the pandemic. When Australia called in April 2020 for an international inquiry into the origins of the COVID-19 in Wuhan, China’s ambassador to Canberra attacked Australia as “hostile” and predicted trade retaliation. China imposed tariffs and unofficial customs bans on coal, barley, beef, wine, timber, lobsters, and cotton.

Australian exporters shifted to other markets. And China could not do without Australia’s iron ore, so Australia’s trade surplus with China kept surging, despite the bans. A study by the government’s Productivity Commission found that China failed to “impose significant economy-wide costs on Australia” although individual businesses were hit. The Commission said “alternative markets were readily found for many exports” and exports “proved to be mostly resilient against these [Chinese] trade measures.” Barley and coal exporters found other markets, the study said, and the value of beef and wheat exports to China did not fall significantly because the partial bans targeted certain abattoirs and shipments.

After Labor won office in Australia’s federal election in May 2022, China’s first move was to end the freeze on ministerial meetings. Then China started peeling back sanctions. Beijing lifted its barrier to Australian coal in January 2023, allowing customs clearance for coal shipments for the first time since 2020. In May 2023, Australia’s trade minister and China’s commerce minister co-chaired a Beijing meeting of the Joint Ministerial Economic Commission, the first time the commission had convened since 2017. It was the first in-person meeting of Australian and Chinese trade ministers since 2019. Canberra described the talks as “an important further step towards the stabilization of Australia’s bilateral relationship with China.” Following the meeting, China said it would resume imports of Australian timber.

In August 2023, China announced it would remove 80.5% of anti-dumping and countervailing duties on Australian barley. The barrier had blocked all Australian barley exports from May 2020. With the removal of the duties, Australia dropped legal action at the World Trade Organization. Canberra welcomed the action as “another positive step towards the stabilization of our relationship.” Beijing reinstated Australia as an Approved Destination for group travel by Chinese tourists. Prior to the pandemic, China was the largest and most valuable market for travelers coming to Australia; in 2019, more than 1.4 million Chinese tourists visited.

Australia’s Trade Minister, Don Farrell, described the progress in a speech in June: “One of our biggest priorities has been to work to stabilize our relationship with China—by far our largest trading partner. We’ve been clear on our position with China from day one. We want a stable and prosperous trading relationship, and the full resumption of trade. Since the day I took on the job as Australia’s Trade and Tourism Minister, it has been the biggest test of our commitment to stability, to pursue discussion over dispute, and dialogue over bluster.”

The experience taught Australia that “overreliance on any single trading partner comes with risks,” Farrell said. “Any business that relied on a single client, would be destined for failure, so too for global trading economies. We’ve learnt valuable lessons over the last few years.” Australia’s wine makers hope their stabilization turn comes quickly. China’s ban has caused a wine glut. Australia has an oversupply equivalent to more than 2.8 billion bottles, because China was previously the biggest buyer of Australian wine. In July, Australian Foreign Minister Penny Wong met China’s top diplomat Wang Yi for the fourth time in a year, at the ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ meeting in Jakarta. Wong aimed to refine the terms for Albanese to visit China, telling reporters: “The prime minister has been invited to Beijing. We would hope for the most positive circumstances for such a visit.”

With progress on trade, attention turns to two Australian citizens held hostage by China: Cheng Lei and Yang Jun (also known Yang Hengjun). Yang, a writer and blogger, has been detained for more than four years. Yang migrated to Australia in 1999 and gained citizenship. Prior to his arrest, he was based in New York and was a visiting scholar at Columbia University. Journalist Cheng Lei is a Chinese-born Australian who was a reporter and presenter for China’s English-language TV news channel from 2012 to 2020. In August 2020, Australia was notified that she had been detained for endangering China’s national security. Cheng Lei’s first public statement since her arrest came in August in what she called a “love letter” to Australia, dictated to consular staff during a visit:

“I relive every bushwalk, river, lake, beach with swims and picnics and psychedelic sunsets, sky that is lit up with stars, and the silent and secret symphony of the bush. I secretly mouth the names of places I’ve visited and driven through. I miss the Australian people…I miss the sun. In my cell, the sunlight shines through the window but I can stand in it for only 10 hours a year. Every year the bedding is taken into the sun for two hours to air. When it came back last time, I wrapped myself in the doona and pretended I was being hugged by my family under the sun.”

Albanese says the government pushes for release of its citizens “whenever Australia meets with China.” Canberra has been careful not to use the term “hostage” in official comments, and the prime minister says the release of the two Australians is not a condition for his Beijing visit. Beijing’s view of stabilization was given in a China Daily editorial in August on a “good reboot” with Australia based on “a tacit consensus” to “let the past be past.” The Chinese Communist Party’s English-language paper observed that Canberra and Beijing had met half-way: “However, although China remains consistent in its policy toward Australia, Beijing has no reasons not to remain aware of the fact that Australia exists in almost all anti-China cliques of the United States, ranging from AUKUS and the (“Quadrilateral Security Dialogue”) to the so-called Five Eyes intelligence alliance. This is also something that does not change no matter who becomes the leader of the country. Yet something else that has not changed is that China has been and will continue to be Australia’s largest export market.” The irony of stabilization is that China is set to deliver significant trade hits to Australia, even if these are unintentional rather than policy. The economic aliments afflicting China mean Australia’s top customer will pass on some of its pain.

Balancing China and Defense Strategy

Surveying the “regional balance of power” in April, Foreign Minister Wong said Australia started with “the reality that China is going to keep being China” and Canberra would not “waste energy with shock or outrage at China seeking to maximize its advantage.” Australia must focus on its interest in “rules, standards and norms—where a larger country does not determine the fate of a smaller country.” The competition in the Indo-Pacific, Wong said, “is more than great power rivalry and is in fact nothing less than a contest over the way our region and our world work.”

Australia’s stabilize effort has a mantra used in government statements and interviews. Wong hit every note in her balance-of-power speech: “Cooperate where we can, disagree where we must, manage our differences wisely, and above all else, engage in and vigorously pursue our own national interest.”

In April, the Albanese government released a Defense Strategic Review (DSR) to set the agenda “for ambitious, but necessary, reform” to the posture and structure of Australia’s defense. The DSR was prepared by a former Labor foreign and defense minister, Stephen Smith, now Australia’s ambassador to London, and Sir Angus Houston, a former chief of the Australian Defense Force (ADF). A striking element of their report was the government’s adoption of its tough judgment about the inadequate state of the ADF. The Deputy Prime Minister and Defense Minister Richard Marles wrote: “Due to the significant changes in Australia’s strategic circumstances, the Government agrees with the Review’s finding that the ADF as currently constituted and equipped is not fully fit for purpose.”

The government accepted the review recommendations, and identified six priorities:

- Acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines through AUKUS to improve deterrence;

- Developing the Australian Defense Force’s (ADF) ability to precisely strike targets at longer-range and manufacture munitions in Australia;

- Improving the ADF’s ability to operate from Australia’s northern bases;

- Initiatives to improve the growth and retention of a highly skilled Defense workforce;

- Rapidly translate disruptive new technologies into ADF capability, in close partnership with Australian industry; and

- Deepening of our diplomatic and defense partnerships with key partners in the Indo-Pacific.

To enhance the ADF’s strike capability “and hold an adversary at risk at longer ranges,” the government in August announced the purchase of 200 Tomahawk cruise missiles and 60 extended-range missiles to target enemy radar systems. The number of High Mobility Artillery Rocket System (HIMARS) launchers being acquired for the ADF will be doubled to a total of 42. The review by Smith and Houston described a radical shift in the Indo-Pacific: “Intense China-United States competition is the defining feature of our region and our time.” For the first time in the 80 years since World War 2, Australia faced the highest level of strategic risk: “the prospect of major conflict in the region that directly threatens our national interest.”

In the government’s National Defense Statement issued along with the DSR, Marles blamed China’s build-up for the contest: “Australia’s region, the Indo-Pacific, faces increasing competition that operates on multiple levels — economic, military, strategic and diplomatic—all interwoven and all framed by an intense contest of values and narratives. A large-scale conventional and non-conventional military build-up without strategic reassurance is contributing to the most challenging circumstances in our region for decades. Combined with rising tensions and reduced warning time for conflict, the risks of military escalation or miscalculation are rising.”

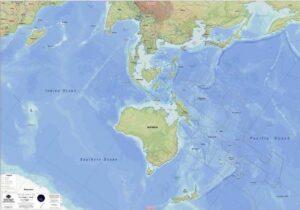

The DSR said China’s military surge was the largest and most ambitious of any country since the end of the Second World War “This build-up is occurring without transparency or reassurance to the Indo-Pacific region of China’s strategic intent.” The review said China “threatens the global rules-based order in the Indo-Pacific in a way that adversely impacts Australia’s national interests.” For students of Australian defense epistemology, the DSR offered a new map of “Our Strategic Environment.” It was the only map in the 110-page report; given how much the military love maps, that sparked much discussion in the officer caste and strategic class. The review said Australia’s adoption of an Indo-Pacific strategy since 2013 was a “deeply significant change to the basis of Australian defense planning.” This is the DSR’s map of the Indo-Pacific, which it calls “the most important geostrategic region in the world.”

Figure 1 Australian government, Defense Strategic Review

The map grabbed the attention of Kim Beazley, former Labor leader, defense minister and Australia’s ambassador to Washington from 2010 to 2016. Beazley wrote that the map “superbly situates us” and explains why the US seeking a major role in the Indo-Pacific “would consider Australia to be critical. Australia points straight into the archipelago that connects the Indian and Pacific oceans. Our land mass is immense, even alongside Asia. It suggests that Australia is a potent piece of real estate and a valuable US ally.”

US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin welcomed the DSR as demonstrating Australia’s commitment to meet regional and global challenges, and to “our Unbreakable Alliance, which has never been stronger.” He said the review showed “the pivotal role Australia plays in preserving a free and open Indo-Pacific, including through participation in AUKUS and the Quad.”

A DSR commentary from the International Institute for Strategic studies noted that the ADF will remain relatively small in numbers, limiting its operations and sustainment. In a crisis over Taiwan or conflict involving Japan or South Korea, IISS judged, Australia’s “preferred option” would be rear-guard operations further afield from the main theatre of operations. Such a planning assumption could be “too optimistic, given that the US may expect more from the ADF as part of an allied response in the event of a full-scale Chinese invasion of Taiwan.”

AUKUS and Nuclear Submarines

Figure 2 Official logo of AUKUS www.asa.gov.au/aukus

On March 13, 2023, the leaders of Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States marked the end of 18 months of consultation by announcing the plan for Australia to acquire conventionally armed nuclear-powered submarines under the AUKUS security partnership. Anthony Albanese, Rishi Sunak and Joseph Biden met in San Diego to set the pathway to build nuclear-powered submarines that will be named SSN-AUKUS (SSN stands for Submersible Ship Nuclear).

Figure 3 Australia’s Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, US President Joseph Biden, and UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak at the AUKUS announcement in San Diego. Image: Anthony Albanese/Twitter

The cost of Australia’s submarines is A$368 billion (US$245 billion) over the three decades to 2052-53, according to figures given to the Parliamentary Budget Office. Australia’s annual defense budget this year is A$52.5 billion (US$35 billion), the first-time annual funding has exceeded A$50 billion. Defense Minister Marles says the best estimate of the cost of the boats is 0.15% of Australia’s gross domestic product over the life of the program. SSN-AUKUS will be a common platform operated by both the UK and Australia, with two productions lines–one at Barrow-in-Furness in the UK, and one at Osborne in South Australia. Nuclear reactors for the Australia’s AUKUS submarines will be built in the UK.

In the late 2030s, the UK should deliver its first SSN-AUKUS boats to the Royal Navy. Australia aims to deliver the first SSN-AUKUS built in Australia to the Royal Australian Navy in the early 2040s. Australian navy and civilian personnel have started to embed with the US Navy and Royal Navy. From 2027, the UK and US will rotate nuclear submarines to HMAS Stirling naval base, near Perth in Western Australia. The rotation will ultimately comprise one UK Astute-class submarine and up to four US Virginia-class submarines. The US has promised that in the early 2030s it will sell Australia three Virginia-class submarines, with the potential to sell up to two more if needed. The “if needed” hedge for two extra Virginia boats is in case Australia is not producing its own AUKUS boats by the 2040s. Getting three Virginias in the 2030s would bridge the capability gap as Australia retires its Collins-class diesel-electric submarines from 2038.

Australia plans to buy two serving Virginia boats from the US Navy while the third boat will be a new Virginia off the US production line. The US has never before transferred a nuclear-powered submarine to another navy. Australia wants the two serving boats from the US Navy to have a further 20 years of life (the Virginias have a service life of 33 years). In June, the US House of Representatives referred to committees draft legislation for the sale to Australia of two Virginia-class submarines from the inventory of the US Navy. Evidence to Senate hearings in Canberra is that the Australia aims to have eight nuclear SSNs in the 2050s: three Virginia-class and five AUKUS.

In July, Canberra created the Australian Submarine Agency to acquire, construct, deliver, technically govern, sustain, and eventually dispose of Australia’s nuclear submarines. In a major speech on foreign policy and defense, Albanese used his keynote address to the Singapore’s Shangri-La Dialogue to argue that AUKUS would give fresh support to Australia’s long engagement in Asia and the South Pacific: “Before I stood alongside President Biden and Prime Minister Sunak to announce Australia’s pathway to acquiring conventionally armed, nuclear-powered submarines, I ensured that my government spoke with every ASEAN and Pacific partner and many other nations. More than 60 phone calls, being open and transparent with the region about our intentions.”

Albanese quoted Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo’s view that the Quad and AUKUS should work as “partners and not competitors” in making the region stable and peaceful. Albanese said: ‘The submarines we are acquiring—the single biggest leap in Australia’s defense capability in our history—reflect our determination to live up to those expectations. To be a stronger partner and a more effective contributor to stability in our region.”

As well as making the case to the region, Albanese had to persuade his own party. AUKUS was a controversial focus of the national conference of the Australian Labor Party, the peak meeting every three years when Labor adopts its formal policy platform. Prior to the August conference, party members and union leaders campaigned to sink the deal for nuclear subs. The strongest anti-AUKUS argument was from former Labor Prime Minister Paul Keating. In a speech to the National Press Club, Keating called AUKUS “the worst international decision by an Australian Labor government” in 100 years.

Keating said Australian interests were being subsumed to its allies, with “defense policy substituting for foreign policy.” Despite the enormous cost, Keating said, the AUKUS boats did not “offer a solution to the challenge of great power competition in the region or to the security of the Australian people and its continent.” The Albanese government wanted the submarines for deep and joint operations against China, Keating said: “No mealy-mouthed talk of ‘stabilization’ in our China relationship or resort to softer or polite language will disguise from the Chinese the extent and intent of our commitment to US strategic hegemony in East Asia with all its deadly portents.”

At the national conference, Albanese and his ministers repelled the effort to strip AUKUS from Labor’s policy platform. The prime minister told the conference: “AUKUS is the choice of a mature nation, an honest global player taking our rightful place on the world stage.” Heading off any party revolt, Deputy Prime Minister and Defense Minister Richard Marles had the conference adopt a 32-paragraph statement on the importance of AUKUS. The statement said AUKUS is needed for “strategic equilibrium” and to “play our part in collective deterrence of aggression.” Building the submarines in Australia would create around 20,000 direct jobs and see $30 billion invested in the nation’s industrial base. “Australia will always make sovereign, independent decision” on the use of the submarines,” the policy statement said, and AUKUS “does not involve any ante facto commitment to participate in, or be directed in accordance with, the military operations of any other country.”

The Marles motion was passed on the voices, with no vote demanded, and becomes Labor policy. Writing AUKUS into the platform confirms the nuclear submarine consensus between Australia’s parties of government, Labor and the Liberal-National Coalition. The nuclear allergy that defined Australian politics for decades has been remade with extraordinary speed. The Coalition Prime Minister Scott Morrison unveiled AUKUS in September 2021—cancelling the contract for a French-designed conventionally-powered boat—and giving Labor leader Albanese only 24-hours notice to back the switch to a nuclear-powered boat. Albanese dodged Morrison’s political “wedge” and endorsed AUKUS, a position that is now formal Labor policy.

The view from Washington is that Australia must prove worthy of US nuclear “crown jewels.” That’s the perspective of Arthur Sinodinos, who completed his term as Australia’s ambassador to the US in March, as the AUKUS details were being announced in San Diego. Sinodinos, a former Liberal senator and government minister, describes the nuclear submarine project as a “moonshot” for Australia. Sinodinos told The Australian newspaper (Feb. 25-26) that the US was handing over sovereign capability so Australia could build its ability to project power into the region: “We’ve got the Americans to sign off on giving us access to the crown jewels of their nuclear technology. And they’re prepared to trust us based on verification—trust but verify—on our capacity for nuclear stewardship. So, it’s a very big effort we’re embarked on. It will test us as a nation.”

US Alliance

President Biden will host Prime Minister Albanese for an official visit to the US and a state dinner on Oct. 25. The White House said the visit “will underscore the deep and enduring alliance” and their “shared commitment to supporting an open, stable and prosperous Indo-Pacific.” Albanese said his first visit to Washington as prime minister would strengthen a relationship that is “unique in scale, scope and significance, reflecting more than 100 years of partnership.” While AUKUS expresses the alliance’s ambition for coming decades, today’s action is an alliance coming home to Australia. The US military commitment is being expressed on Australian soil.

The Labor government maintains that the use of Australia by US military planes, ships and troops are “rotations,” thus denying that the US is establishing “bases” on Australian soil. The rotation-vs-bases distinction points to the politically sensitive balance between alliance commitment and national sovereignty. Australia has become used to hosting permanent intelligence bases. The intelligence model is the Pine Gap base near Alice Springs. The Pine Gap “joint defense facility” is a satellite surveillance station operated by the Central Intelligence Agency, commissioned in 1967. Next year the Australian and US militaries will go a step further to create their own combined intelligence center.

Using force “rotations,” Australia’s intimate involvement with US intelligence is being replicated in the military realm. The Labor government set its alliance template with the annual AUSMIN defense and foreign policy talks held in Washington in December 2022 and in Brisbane in July 2023. The rotation of US Marines through Australia agreed in 2011 is being emulated by the other arms of the US military. The approach was designed by the previous Liberal-National Coalition government and Labor is building the detail.

In 2020, the Coalition government signed a statement of principles on alliance cooperation and force posture priorities in the Indo-Pacific, and in 2021 Australia and the US announced a program of “force posture cooperation and alliance integration.” The era of integration, as defined by the 2021 AUSMIN communiqué, focuses on what more the US military will do in Australian through “the rotational deployment of US aircraft of all types,” increased support for US ships and submarines, and combined logistics, sustainment, and maintenance for “highend warfighting and combined military operations in the region.”

Serving integration, the Labor government last year agreed that the US will “preposition stores, munitions, and fuel” in Australia, in support of US capabilities. To strengthen the US land presence, Australia will “expand locations for US Army and US Marine Corps” to use for exercises and regional engagement.

To help the US Air Force, more infrastructure will be built in northern Australia at what are termed “bare bases.” Australia and the US will co-develop the bare bases “to support more responsive and resilient rotations of US aircraft.” The major airbases in the Northern Territory, Darwin and Tindal (near Katherine), are already being upgraded. Tindal’s improvements will allow it to house up to six US B-52 bombers for “squadron operations.”

The Brisbane AUSMIN in July announced agreement on the creation of “Combined Intelligence Center–Australia,” to start operation next year. The joint center will be within Australia’s Defense Intelligence Organisation to enhance cooperation with the US Defense Intelligence Agency, focused on “issues of shared strategic concern in the Indo-Pacific.” Defense Minister Marles said the new intelligence center is a “significant step forward” toward “seamless” intelligence ties with the US: “You’ll get an American perspective into the American system seen from Australia. And that is not insignificant.” During his first visit to Washington as defense minister last year, Marles said he aimed to “operationalize” the US presence in Australia, to move from “interoperability to interchangeability” so the two militaries could “operate seamlessly together at speed.” From air bases in northern Australia to Canberra’s new combined intelligence center, the coming together in Australia of the US and Australian militaries is, indeed, happening “at speed.”

The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue

Canberra describes its Quad partnership with India, Japan and the US as “a key pillar in Australia’s foreign policy.” The new pillar—or Quad 2.0—is still in the early-build stage. The Labor Party has gone from being negative about Quad 1.0 to positive about Quad 2.0, reflecting the shift in Australia’s view of China. Australia was set to hold only the third in-person Quad leaders’ meeting in Sydney (following the first face-to-face summit in Washington in 2021 and the second in Tokyo in 2022). Everything was arranged for that third in-person Quad on May 24. The stationery, media banners and accreditation lanyards were ready. The draft vision statement was written, along with the draft communiqué. Plus one of Australia’s greatest photo opportunities was prepared—the leaders would stand in front of the magnificent white sails of the Sydney Opera House, looking across Sydney Harbour. After the Quad, President Biden would go to Canberra to address the Australian Parliament.

Then, just days out, the Sydney summit was no more. The prime minister got an early-morning phone call from the president. Biden told Albanese he could not make the Sydney date. Instead, Biden was needed in Washington for crucial negotiations on the US debt ceiling. Much scrambling followed. Biden was still going to the G7 summit in Japan (and the leaders of India and Australia would be G7 guests). So the statement that Biden and Albanese had been due to release in Canberra proclaiming “An alliance for our times” was actually issued in Hiroshima after a meeting on the sidelines of the G7.

In the same way, the third in-person Quad leaders’ meeting took place in Hiroshima, even though Albanese was credited as host. Getting the leaders together was a hasty fix, but their vision statement was another deliberate step in proclaiming what the Quad promises to protect.

As ever with Quad-speak, China is not named. But the Quad vision is defined by how the four partners stare at Beijing, and how they describe the future they want to see. The central Quad-speak hymn is to “a free and open Indo-Pacific that is inclusive and resilient.” The vision is for a region that is “free from intimidation and coercion, and where disputes are settled in accordance with international law.” When Australia ticked/inserted that phrase about “free from intimidation and coercion” in the vision draft, it was thinking about three years of trade pressure from China. Canberra’s description of the Quad as a new foreign policy pillar points to its uses as a protection against China. The Quad offers mutual reassurance to the four members—and assurance to the rest of the Indo-Pacific about a future where China’s importance does not have to mean Beijing’s total dominance.

After the improvised Quad summit in Hiroshima, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi flew to Australia, as had been scheduled. His talks with Albanese were the sixth time the two leaders had met in the first year of Albanese’s prime ministership. The growth of Australia’s bilateral relationship with India is feeding into the Quad partnership, just as two decades ago Australia’s bilateral ties with Japan nurtured the trilateral with the US and then the Quad. Next year, India will host the annual in-person Quad summit. India’s status as the new but demanding great friend that must be courted—as opposed to Australia as an old ally, reliable and understanding—makes India’s Quad meeting a “must” for the US president, whatever the state of play in Washington (even in an election year).

Australia and the US in the South Pacific

When President Biden cancelled his trip to Australia in May, he also cancelled another leg—a visit to Papua New Guinea to meet PNG’s prime minister and other leaders of the Pacific Islands Forum. It was a stutter in Washington’s “renewed partnership with the Pacific Islands.” The South Pacific has become part of the great-power competition in the Indo-Pacific. The island states detest the power elements of the new reality, while enjoying the increased attention. The South Pacific worry is that the Indo-Pacific subsumes or marginalizes their islander identity in a much larger Asian construct, and ties the peace of the islands to a dangerous Asian contest. Echoing Southeast Asia, the South Pacific pleads that it must not be forced to choose between China and the US.

Competition with China means the US is back in the South Pacific to help Australia’s effort to retain the major regional role. Development joins diplomacy and defense in the way the US and Australia draw together. The US can no longer leave the region to Australia as it has for the last 50 years. As the colonial era ended and the modern South Pacific of independent states arrived in the 1960s and 1970s, the US handed significant regional responsibility to Australia and New Zealand. Washington advised that Canberra and Wellington should “shoulder the main burden.” The US would do the duties of the big external power in Micronesia while Australia and New Zealand would have that role in Melanesia and Polynesia. Australia’s immediate geographic focus is Melanesia while these days New Zealand ponders the idea of Polynesia shaping its international understanding with a “Maori foreign policy.”

To see how that original allocation of responsibility was agreed, turn to Australian Cabinet documents. In a March 1977 Cabinet submission on Australian diplomatic representation in the South Pacific, Foreign Minister Andrew Peacock stressed the “urgent need for Australia to extend its official presence in the South Pacific,” because of efforts by the Soviet Union and China to increase their roles in the islands. Peacock wrote that Washington expected Canberra and Wellington to carry the South Pacific load: “In discussions on Soviet and Chinese motives in the region, the United States Government has made it clear that, while it stands ready to play a supporting role, it looks to Australia and New Zealand to shoulder the main burden of ensuring the stability of the region and of developing close relations with the Island countries. The United States also looks to Australia and New Zealand to provide most of the basic reporting and intelligence on the countries of the region.”

Peacock repeated the message of South Pacific responsibility—and the complications involved—in a Cabinet submission on US relations in December 1978: “The Americans have looked to Australia and New Zealand to take the lead in the South Pacific, but have accepted Australian encouragement to take a more active role in the region. In view of Island sensitivities, Australia will need to exercise care in interposing itself between South Pacific countries and the US.”

The effect of the division of responsibilities over the five decades was most evident in the diplomatic, political, and intelligence realms. A negative read would be that Washington went absent for long periods in Melanesia and Polynesia. A kinder read is that Washington expected its allies to take more responsibility and had confidence in Australia and New Zealand to serve their own interests and their own region. The strategic division established in the 1970s has run its course. Both Canberra and Washington agree: the US has to get back in the game in the South Pacific because China has changed the game. What holds for the Indo-Pacific is equally true for the South Pacific.

The US has to address “long years of relative neglect,” observed former Australian diplomat Richard Maude, arguing “US interests are largely defined by China’s gains.” The first US summit with South Pacific leaders in September last year can be read as a simple statement: “We’re back!” The White House said the Washington meeting with island leaders reflected a “broadening and deepening” of the US role. The summit’s declaration promised Washington would “recommit” to working with the South Pacific to deal with “a worsening climate crisis and an increasingly complex geopolitical environment.”

The substance of that deeper role must be a US that is constantly present in the South Pacific and delivers for islanders. Hear that from the doyen of Solomon Islands journalism, Dorothy Wickham, in a New York Times op-ed. She offers a simple lesson for the US as it vies with China:

“You have got to show up. We get it. The Solomon Islands is small, remote and economically insignificant. But if all countries like us are dismissed as such, China will pick us off one by one with its promises of business projects and development aid…There is a creeping sense today that we are being ignored, if not forgotten. So who can blame us if we open the door to new friends who can help with our needs? And those needs are great.”

In the South Pacific, foreign policy is often aid policy. Washington and Canberra last year agreed on regular consultations on their aid work in the islands. Australia’s Minister for International Development and the Pacific, Pat Conroy, who also serves as minister for defense industry, had talks in Washington in October 2022 with the administrator of USAID, Samantha Power. After the meeting, Power pointed to the “strong need” for the two aid agencies “to work even more closely together” to deal with complex geopolitical challenges.

In August, USAID reopened a Pacific Islands mission in Fiji to oversee regional aid programs in Micronesia and Polynesia. At the same time, USAID’s office in Papua New Guinea was elevated to have a broader Melanesian focus, with Solomon Islands and Vanuatu. After opening the Suva mission, Power told the US Indo-Pacific Command Chiefs of Defense Conference, held in Fiji, that “as the United States deepens our commitment to security in the Pacific, we are expanding our investments across all these lines of effort—diplomacy, defense, and development.”

Canberra’s effort to align its development effort with strategic policy was the release in August of a new international aid framework. Australia wants to maintain its top spot as the largest aid giver in the South Pacific, seeking to be the region’s “partner of choice.” Australia joins its development to its diplomatic and defense policies because of what the aid policy described in its first two sentences: “Our region is under pressure. We face the most challenging strategic circumstances in the post-war period.”

The name “China” does not appear in the aid framework. But the frame defines itself in important ways by the contrasts it offers with China. One example is Australia’s implied swipe at how China delivers aid by building the debt of island states: “Public debt in the Pacific is expected to almost double by 2025, compared to 2019. The increase in the debt servicing burden will exacerbate challenges and impact critical health, education, and social services.” Australia promises to deliver aid that is “transparent, effective, and accountable.” And in a related shaft at Chinese projects built by Chinese companies and workers, Australia’s promise is to “support local actors.”

The US and Australia embraced the Pacific Island Forum’s “Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continent” as a means to deliver what the South Pacific needs by working with the “Pacific way.” In September 2022, the Partners in the Blue Pacific had their first meeting, drawing together the US Australia, Japan, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom, for talks with Forum members. Observers at the first meeting were Canada, France, Germany, India, South Korea and the European Union. The promise is of a “genuine partnership” that will be “led and guided by the Pacific islands.”

The Quad is playing its part in the South Pacific with the creation last year of the Indo-Pacific Partnership for Maritime Domain Awareness (IPMDA). The partnership uses commercial satellites to provide “real time” data on what ships are doing in national waters. The work targets illegal fishing. Chinese fishing boats often turn off their automatic identification transponders to evade detection. Under IPMDA, Australia in July awarded a satellite contract to provide space-based radio frequency data and analytics to the Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA). Based in Solomon Islands, the FFA helps 17 island states manage tuna fisheries within their 200 mile Exclusive Economic Zones.

Kevin Rudd Foes to Washington

Australia’s new ambassador to the US is Kevin Rudd, who was Australia’s 26th prime minister (from 2007 to 2010, and after a caucus coup returned as PM for three months before losing the 2013 election). Rudd presented his credentials to President Biden in April 2023. Australia has sent plenty of former politicians to head the Washington embassy, but never a previous prime minister. Rudd is the 11th Australian politician to serve as ambassador in Washington since the post was established in 1940 (the other 12 ambassadors during the period were public servants). Most Australia ambassadors around the world are career diplomats, but in Washington the politicians are tightening their hold—Rudd’s three predecessors as ambassador to the US were former members of federal Parliament.

The only Australian precedent for an ex-PM becoming an ambassador is with Britain. Australia’s fifth prime minister, Andrew Fisher, resigned as PM in October 1915 to become high commissioner to the UK, serving for the rest of WW1 and on until 1921. The eighth prime minister, Stanley Bruce, later became high commissioner to the UK from 1933 to1945, serving through the depression and WWII. The lesson seems to be that Australia’s former leaders do diplomatic service with the key international partner (and protector) when times are tough. Since losing office in 2013, Rudd has spent most of his time in the US, going first to Harvard’s Kennedy School. In 2015, he became inaugural president of the Asia Society Policy Institute in New York. In 2020, he was appointed President and CEO of the Asia Society globally.

Figure 4 Ambassador Kevin Rudd presents his credentials to President Joe Biden at the White House, alongside wife Thérèse Rein, April 19, 2023. Picture: Kevin Rudd/Twitter

Announcing Rudd’s appointment, Prime Minister Albanese and Foreign Minister Wong described Rudd as one of “the world’s most eminent and sought-after experts on China and US–China relations. At a time when our region is being reshaped by strategic competition, our interests are well served with a representative of Dr Rudd’s standing.” Rudd received a PhD from Oxford University last year for a thesis on “significant change in China’s ideological worldview under Xi Jinping.” Rudd summarized Xi’s approach as a new form of “Marxist-Leninist Nationalism” or “Marxist Nationalism.” One consular case that sits on Rudd’s desk is the negotiations between the US and Australia over the fate Australian citizen Julian Assange, the founder of Wikileaks. The US seeks to extradite Assange from the United Kingdom on 18 charges related to the publication of thousands of military and diplomatic documents. Assange has been in prison in London for more than four years, fighting the UK’s extradition decision.

A multi-party delegation of Australian federal MPs and senators will travel to Washington on Sept. 20 to urge the US to drop charges against Assange. Among the delegation is a former Coalition deputy prime minister, Barnaby Joiyce, who says the US prosecution sets a dangerous precedent, that a citizen can be sent to a third country for an offence they did not commit in that country. Albanese says his government is pushing against the US over the case. “This has gone on for too long. Enough is enough,” the prime minister said. The US ambassador to Australia, Caroline Kennedy, said in August that a plea deal could end the pursuit of the Australian citizen. Kennedy said the case was “not really a diplomatic issue, but I think there absolutely could be a resolution.” Surveying his tasks as ambassador in Washington, Rudd used an interview in June to list priorities:

Geopolitics, guardrails and strategic stability: “How do we preserve the peace between the United States and China and what is the role of allies in the process?”

Taiwan: How to deter China from “resort to unilateral force to take Taiwan? That’s a complex equation. It’s not just a simple military equation. It’s a broader equation than that.”

Trade and economics: To help Australian industry in the US, in areas from biotechnology to energy and critical minerals. On biotechnology, Rudd notes that 11% of the world’s clinical trials are done in Australia, even though the country has only 0.3% of the world’s population. “So in bio there’s a huge and new dynamic industry.” The aim of AUKUS is “to create a seamless defense, science, and technology industry,” Rudd said, and the joining of Australian, US and UK industry “is potentially even more revolutionary than the submarine project in itself.”

Climate: Along with security and economic engagement, Rudd said, climate policy becomes “the third pillar of our relationship.” Climate action would become “the flipside to energy security.”

Rudd has written a 420-page handbook to help in his new job. Last year he released The Avoidable War: The Dangers of a Catastrophic Conflict between the US and Xi Jinping’s China. Henry Kissinger distilled Rudd’s book to one question: “Can the US and China avoid sleepwalking into a conflict?” Rudd warns that “a war between China and the US would be catastrophic, deadly and destructive. Unfortunately, it is no longer unthinkable.” He concludes that “armed conflict between China and the US over the next decade, while not yet probable, has become a real possibility.” Rudd’s answer to the “unfolding crisis” is what he calls “managed strategic competition.” The managed competition between the US and China, he writes, would aim for “strategic stability,” to allow “new levels of trust” to emerge through experience, and eventually “new modes of thinking about each other.” Ambassador Rudd is now in place in Washington to do what he can for managed strategic competition.

Sept. 7, 2022: Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and President Dr. Jose Ramos-Horta of Timor-Leste sign a Defense Cooperation Agreement.

Sept. 23, 2022: Foreign Minister Penny Wong tells the UN General Assembly that Australia will seek a seat on the UN Security Council for 2029-2030.

Sept. 23, 2022: On the margins of the UN in New York, FM Wong meets China’s Foreign Affairs Minister Wang Yi to discuss “stabilizing” the Australia-China relationship.

Sept. 24, 2022: Australia, the United Kingdom, and the US mark one-year anniversary of the AUKUS trilateral agreement, saying “significant progress” has been made toward Australia acquiring nuclear-powered submarines.

Oct. 6, 2022: Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare visits Canberra for talks with PM Albanese, reaffirming “mutual security commitments.”

Oct. 10, 2022: The annual Australia-India Foreign Ministers’ Framework Dialogue is held in Canberra, the second visit to Australia in the year by India’s External Affairs Minister Dr. S. Jaishankar.

Oct. 18, 2022: Singapore’s Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong and PM Albanese hold 7th Australia-Singapore Annual Leaders’ Meeting in Canberra.

Oct. 22, 2022: Japan’s Prime Minister Kishida Fumio and PM Albanese sign a Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation.

Nov. 13, 2022: ASEAN, Australia and New Zealand announce the “substantial conclusion” of negotiations to upgrade the ASEAN-Australia-New Zealand Free Trade Agreement.

Nov. 15, 2022: PM Albanese meets China’s President Xi Jinping on the margins of the G20 Summit.

Nov. 18, 2022: Professor Sean Turnell returns to Australia, following what Canberra describes as “more than 21 months of unjust detention in Myanmar.”

Nov. 28, 2022: Australia lowers its terrorism threat level from Probable to Possible. The level had been set at Probable for eight years.

Dec. 6, 2022: The annual AUSMIN ministerial meeting is held in Washington. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin host FM Wong and Deputy PM and Defense Minister Marles.

Dec. 7, 2022: AUKUS partnership is discussed at Washington talks involving Deputy PM and Defense Minister Marles, British Defense Secretary Ben Wallace and US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin.

Dec. 10, 2022: Australia announces Magnitsky-style sanctions on 13 individuals and two entities “involved in egregious human rights violations and abuses” in Iran and Russia.

Dec. 10, 2022: Australia hosts first negotiating round of the US-proposed Indo-Pacific Economic Framework. Other founding members of the IPEF attending the Brisbane conference are Brunei, Fiji, India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand, the US, and Vietnam.

Dec. 13, 2022: Vanuatu and Australia sign a bilateral security agreement.

Dec. 20, 2022: Previous Labor Prime Minister Kevin Rudd is appointed to as Australia’s next ambassador to the United States.

Dec. 21, 2022: FM Penny Wong travels to Beijing to meet China’s State Councilor and Minister of Foreign Affairs Wang Yi for the 6th Australia-China Foreign and Strategic Dialogue—the first time the dialogue has been held since 2018. The meeting coincides with the 50th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between Australia and China. Opening the dialogue, Wong says Australia and China can “navigate our differences wisely.”

Dec. 29, 2022: Australia-India Economic Cooperation Trade Agreement enters into force.

Jan. 5, 2023: Australia’s stock market surges following reports that Chinese officials are discussing resuming imports of Australian coal, ending a two-year ban.

Jan. 12, 2023: At the Papua New Guinea-Australia Leadership Dialogue in Port Moresby, PM Albanese and PNG Prime Minister James Marape agree to a timeline for negotiations on a new security treaty.

Jan. 19, 2023: FM Wong notes the fourth anniversary of Dr. Yang Jun’s detention in China, stating Australia “is deeply troubled by the ongoing delays in his case” and that Yang “still awaits a verdict.”

Jan. 30, 2023: Second Australia-France Foreign and Defense Ministerial Consultations are held to “restore” the relationship following the 2021 row when Australia abandoned a French-designed submarine in favor of AUKUS. The Paris meeting agrees to joint supply of 155-millimeter ammunition to Ukraine.

Feb. 16, 2023: A new Pacific Engagement Visa will allow up to 3,000 nationals from Pacific island countries and Timor-Leste to migrate to Australia as permanent residents each year.

Feb. 24, 2023: Marking the one-year anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Australia announces more military aid to Ukraine and further sanctions against Russia.

March 8, 2023: PM Albanese makes first visit to India by an Australian prime minister since 2017.

March 15, 2023: Flying back from the AUKUS announcement in the US, PM Albanese calls in Suva to address the concerns of Fiji’s about the nuclear submarine program.

April 11, 2023: Australia announces temporary suspension of its action against China in the World Trade Organization over export duties blocking barley sales to China. Canberra says it “has reached an agreement with China” on a pathway to end the dispute.

April 24, 2023: Defence Strategic Review and National Defence Statement are released.

May 19, 2023: PM Albanese travels to Hiroshima to attend the G7 summit.

May 20, 2023: On sidelines of the G7, PM Albanese hosts third in-person Quad leaders’ summit.

May 22, 2023: India’s PM Narendra Modi travels to Australia following the G7 summit and Quad Leaders’ meeting in Japan.

May 22, 2023: Minister for International Development and the Pacific Pat Conroy travels to Papua New Guinea to represent Australia at the United States-Pacific Island Dialogue, which is co-hosted by PNG Prime Minister James Marape and US Secretary of State Antony Blinken.

May 31, 2023: Australia-United Kingdom Free Trade Agreement enters into force.

June 3, 2023: PM Albanese delivers keynote address to Shangri-La defense dialogue.

June 4, 2023: PM Albanese visits Hanoi to mark 50th year of diplomatic relations with Vietnam.

July 1, 2023: Australian Submarine Agency established to “acquire, construct, deliver, technically govern, sustain and dispose” of Australia’s nuclear-powered submarines, AUKUS.

July 4, 2023: Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo visits Sydney for annual talks, welcoming “substantial progress” in the strategic partnership with Australia.

July 10, 2023: PM Albanese has talks in Berlin with German Chancellor Olaf Scholz.

July 11, 2023: PM Albanese attends the NATO Leaders’ Summit in Vilnius, Lithuania.

July 22, 2023: USS Canberra is commissioned in Sydney.

July 26, 2023: PM Albanese meets New Zealand Prime Minister Chris Hipkins in Wellington for annual talks on the bilateral relationship that “is unlike any other.”

July 28, 2023: During Exercise Talisman Sabre, four Australian soldiers are killed when a helicopter crashes in waters off Queensland’s Whitsunday Islands.

July 29, 2023: 33rd Australia-United States Ministerial Consultations (AUSMIN) is held in Brisbane, involving FM Wong and Deputy PM and Defense Minister Marles, with US Secretary of State Blinken and Secretary of Defense Austin.

Aug. 8, 2023: Australia’s new International Development Policy is announced.

Aug. 10, 2023: Australia’s military for first time hosts “key partners” India, Japan and the United States for Exercise Malabar.

Aug. 10, 2023: Deputy PM Marles addresses the Australian American Leadership Dialogue.

Aug. 11, 2023: FM Wong notes that it has been three years since Australian citizen Cheng Lei was detained in China.

Aug. 18, 2023: National conference of Australian Labor Party meets to decide policy platform.

Aug. 27, 2023: Three US marines killed when an Osprey aircraft crashes near Darwin during an exercise.