Articles

Inter-Korean relations, still formally in abeyance, were dominated in September and October by a mysterious and tragic incident in the West Sea. A Southern official went missing from a survey vessel and ended up in Northern waters—where he was shot and his body burnt. Kim Jong Un apologized, sort of, and Seoul revealed that he and Moon Jae-in had earlier privately exchanged pleasantries—but neither this, nor Unification Minister Lee In-young’s ceaseless calls for aid and cooperation, cut any ice in Pyongyang. Meanwhile Kim launched a campaign to eradicate Southern slang among Northern youth. In December Moon’s ruling party passed a law to ban propaganda balloon launches across the DMZ, prompting widespread criticism but earning no praise from the North. At a big Party Congress in January, Kim lambasted the South in shopworn terms, withdrew his “goodwill,” and said the ball is in Seoul’s court. For good measure, his sister Kim Yo Jong called South Korea “weird.” Despite Moon’s dreams, the 2018 peace process is over, with scant prospects of renewal.

Introduction

Following a tempestuous summer, literally and metaphorically, for the two Koreas and between them, the last four months of 2020 were mercifully calmer. North Korea continued to cold-shoulder the South, as it has done for two years. The glory days of 2018, with its two substantial inter-Korean accords and three North-South summits—more in six months than in the entire previous 70 years of the peninsula’s division—are beginning to fade into history. Rather than a lasting breakthrough, this has turned out to be just one more false dawn, the latest, and briefest, of several that have come and gone on the peninsula. There was 1972-73, 1984-85, 1990-92, 1998-2007—and, we must now add, 2018. Was, not is.

That is not how South Korea’s current government sees it. President Moon Jae-in remains determinedly upbeat, and newish Unification Minister Lee In-young even more so. Yet the basis for their optimism is hard to fathom. Granted, in recent months Pyongyang has been less rude to Seoul than in June and July, but this merely means being ignored rather than insulted. There is no peace process. Nothing of substance is happening. South Korea keeps trying, making suggestions and offering help—but the North is not interested.

Those clutching at straws may wave one or two. In September, Moon and Kim Jong Un exchanged polite letters—privately. Seoul only revealed this after the North bizarrely and brutally shot and burnt a South Korean apparently trying to defect; this sad, strange episode is discussed below. Kim apologized for that, which is something. Normally, being North Korea means never having to say you’re sorry, to paraphrase Love Story (only their movie is called Hate Story).

Yet Kim has done quite a bit of apologizing recently. While he arguably has much to apologize for, the tone of his speech at 2020’s big event—a military parade marking the 75th anniversary of the ruling Workers’ Party (WPK) on Oct. 10—was remarkable, albeit no doubt calculated, for its tearful moments. Sticking to our inter-Korean remit, this oration included a warm if brief (a single sentence) shout-out to the folks down south:

I also send this warm wish of mine to our dear fellow countrymen in the south, and hope that this health crisis would come to an end as early as possible and the day would come when the north and south take each other’s hand again.

Good to hear, but talk is cheap. Hold hands again? As this journal has chronicled, it was the North which wrested its mitt away two years ago, long before the coronavirus, which Kim falsely implies is the reason why inter-Korean cooperation halted. And as he knows full well, far from attacking him for this rude U-turn, and despite Pyongyang’s confected tantrum in June when it threatened to attack and took the extreme step of blowing up the North-South liaison office, Moon and his ministers have never stopped extending their hands in friendship: urging the North to come back to the table, and constantly offering assistance—including with COVID-19, which the DPRK still claims to be free of. In December, when ROK Foreign Minister Kang Kyung-wha dared to query that unconvincing claim, Kim’s sister Kim Yo Jong broke a six-month silence and snarled at her to shut up. Thankfully briefer than her anti-Moon diatribes in June, this is Pyongyang’s authentic voice. For at the very time in September when Kim was exchanging pleasantries with Moon, on the home front he appears to have launched a fierce propaganda campaign to incite anti-ROK sentiment and stamp out South Korean linguistic and cultural usages—which have evidently taken root in the North.

All of the above was written before Kim Jong Un’s major speech at 2021’s big event: the Eighth Congress of the North’s ruling Workers’ Party in early January. Strictly speaking, this falls outside the past trimester, yet it would be poor service to readers to make you wait till May for details of this key meeting. As discussed below, Kim’s uncompromising stance toward South Korea, as indeed on all other fronts, must surely dispel any shadow of doubt as to Pyongyang’s true attitude.

Smoke on the Water

September began quietly. As noted in our last issue, after June’s frenzy, Northern media fell silent regarding South Korea (see Appendix 2 here): one comment on July 7, then nothing. Seoul, by contrast, was a hive of unreciprocated energy. New MOU Lee was ubiquitous: urging Japan, Russia, and everyone to support inter-Korean relations; hoping (on no visible basis) for family reunions via videolink during Chuseok, Korea’s harvest festival, in autumn; and visiting Panmunjom, where against protocol in the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) he waved toward the KPA soldiers on the Northern side. They were not reported as waving back. More usefully, Lee urged North Korea to implement 2018’s accords, reopen communication lines and resume “open-minded” dialogue; suggesting public health and joint disaster control as promising areas for cooperation. But here again the North did not wave back.

Figure 1 Unification Minister Lee waves to DPRK soldiers at Panmunjom. Photo: Yonhap

All this was swept aside later in the month by a weird and tragic incident. Three months on, facts remain unclear or disputed, and probably always will be. On Sept. 23, South Korea’s Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries (MOF) revealed that two days earlier one of its officials had gone missing from an inspection boat patrolling in waters off Yeonpyeong island, just south of the Northern Limit Line (NLL, the de facto inter-Korean border in the West/Yellow Sea). An intensive search failed to find the man. Intriguingly, MOF added that “according to our military intelligence, he was found in North Korean waters late Tuesday [Sept. 22].” Yonhap, the South’s quasi-official news agency, cited “sources” in the National Intelligence Service (NIS, the ROK spy agency) as adding more and startling detail, saying the as-yet unnamed 47-year old was shot and “cremated” by KPA soldiers, while trying to defect.

The next day, the Ministry of National Defense (MND) weighed in, guns blazing. Citing “our military’s thorough analysis of diverse intelligence,” they claimed that KPA troops found the missing man in DPRK waters—whereupon they shot him, and burnt his body. Condemning this “act of brutality,” MND urged Pyongyang to explain and to punish those responsible. It added that the victim had financial and marital problems, and was probably seeking to defect.

This unusually robust line for Seoul was echoed by the Blue House, which condemned the “inhumane” shooting of a South Korean “who had no weapon and no intention to resist” as an “act against international norms and humanitarianism.” President Moon called the incident “shocking” and intolerable, and ordered the military to further strengthen its security posture. MOU added its own condemnation; noting that it has no means to communicate these sentiments to the North, which cut all inter-Korean communication lines in June. No need to worry, in truth, as for once Pyongyang was most certainly listening.

Further facts and allegations emerged. The official ROK story was that the man took his shoes off (those were found aboard) and left the ship under cover of night, with a flotation device as well as a life jacket. He knew the local currents, which by 3:30 pm on Sept. 22 had carried him some 38 km (a little less than 24 miles) north to Cape Deungsan (Deungsangot) in Northern waters. A DPRK vessel found him there; its crew questioned him—still in the water—from a distance, after first putting on gas masks. He expressed a wish to defect, but they left him in the sea for a further six hours, while seeking instructions. Then, according to the ROK Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS), “at around 9:40 p.m., the North Korean soldiers aboard their vessel shot him before pouring oil over his body and setting it aflame at around 10 p.m.”

How could Seoul possibly know all this? MND cited “our military’s thorough analysis of diverse intelligence.” With so much circumstantial detail, South Korea seemed well able to monitor most of what the North was doing and saying. Torn between not wanting to reveal tricks of the trade, yet keen to cite evidence for their judgments, “sources” revealed much. The KPA’s communications appeared to be thoroughly tapped, with claims that the word “defection” was heard—and that local units had queried (or at least requested reconfirmation of) the order to shoot, when it finally came after a six-hour delay.

One can imagine the flurry in the Blue House as the intelligence came in. First, to determine what exactly happened, and then, how to spin it. The hard line which they settled on reflected Moon’s reported comment, when first apprised of the news, that this is “an issue by which the public would be infuriated.” Dead right. The story was huge, and the universal reaction was shock and anger. Ordinarily, most South Koreans pay little heed to the North, but hopes had been raised in 2018, only to ebb as dialogue stalled. Any lingering faith that Kim Jong Un might still be a trustworthy partner now went up in a literal puff of smoke. Conservatives had long condemned North Korea as barbarous and unpredictable. With this act, the Kim regime as good as (or as bad as) confirmed that judgement. MOU Lee In-young’s preaching for peace, and indeed Moon’s whole Nordpolitik was left looking distinctly naïve.

Kim Jong Un may have had the same thought, and for once sought to save Moon’s bacon. On Sept. 25 the Blue House published a letter from the WPK’s United Front Department (UFD), apologizing for this “unsavory” incident. Yet it is moot how much this helped overall, since the North’s version of events, though detailed, stretched credulity on several points. Claiming that the man gave no clear answers and tried to flee (as well he might, after blanks had been fired at him), the UFD admitted he was then shot, from a 40-50 meter distance—but claimed that when the soldiers came closer no body could be found, only “a large amount of blood.” So it was not his body but “the floating material” [which] “was burned in the water, following the national emergency quarantine regulation.” Few in Seoul were buying that. Pyongyang said it would search for the body, but unsurprisingly nothing was found.

The two governments did not long monopolize the narrative, nor should they. The deceased’s family weighed in. In a Sept. 29 press conference, his elder brother Lee Rae-jin expressed the family’s grief and anger—not only at Pyongyang’s brutality, but also at Seoul on two counts: for publicizing the awful death so graphically, and impugning a devoted public servant by claiming he was trying to defect. True, the deceased had debts—but don’t we all? “Even … Samsung has debts.” Lee Rae-jin also rejected another hypothesis, that this was a suicide.

On Oct. 6 the dead man was finally named. Lee Dae-jun’s teenage son wrote an open letter to Moon, accusing the government of failing to save his father. He disputed the official version: “It doesn’t make sense that my father—a skinny man with a height of 180 cm [5 feet 8 inches] and weighing only 68 kilograms [150 pounds], who had never learned how to swim professionally—rode the tide for 38 kilometers [23.6 miles] … I desperately ask you, Mr President, to please restore my father’s honor.”

Moon Jae-in replied two days later. Offering condolences “with an aching heart,” he promised a fully transparent investigation and urged the family to “please wait for the search result by the coast guard.” Thereafter the story gradually fell off the front pages. The family will be glad to be out of the glare of publicity, but closure must be hard. With North Korea refusing a joint investigation, much about Lee Dae-jun’s tragic end is likely to remain uncertain.

Two assessments may be ventured, regarding his reasons and Pyongyang’s. With all respect to the family, defection does seem the likeliest motive. If he meant suicide, why the flotation device? And leaving his shoes behind hardly suggests an accident. Second, his murderous reception reflects not just North Korean brutality in general, but its paranoia about COVID-19 in particular. As with Kim Jong Un’s over the top reaction to a returning redefector, discussed in our last issue, the DPRK currently takes the medical defense of its borders to extremes. In other fields, this shows up in consumer goods shortages because imports are cancelled or held up at the border, now largely closed even with China. Anyone and anything from outside is seen as a potential coronavirus threat.

Leaders Exchange Pleasantries

Meanwhile the Blue House just seemed relieved that the North had apologized. In a further attempt to calm passions, it revealed that earlier in September Moon and Kim had exchanged letters, whose texts were now published. Moon wrote first, on Sept. 8, offering sympathy as North Korea was hit by successive typhoons and flooding, and praising Kim for his visits “on the frontlines of damage relief.” With the gentlest of hints, he added: “It is regrettable that reality makes us unable to help each other at a time like this, when every day is a crisis.” Still, “We will cheer each other up together as compatriots and overcome it.”

Sept. 12, Kim replied in similar vein, avowing concern at Moon’s “heavy responsibilities,” praising his “uncommon sincerity,” telling him to take “special care” of his health, expressing faith that Moon will “overcome this crisis,” and wishing good health to all South Koreans. All fine and dandy—yet hard to square with North Korea’s bellicose actions in June. He added: “I feel like I can know better than anyone else how arduous it must be for you, Mr. President—how much heavy pressure must be upon you and how much you must be struggling.” Well he knows indeed, for the “pressure” includes not only COVID-19, which Kim stressed, but also two-faced people who insult him, threaten an attack, and then blow up a joint liaison office. But Kim made no reference to this, much less an apology, nor did Moon speak of it.

Given that—let alone what was to follow in January—this exchange of pleasantries, though interesting, seems irrelevant to the real state of inter-Korean relations. Equally meaningless was Kim’s brief apology to Seoul on Oct. 10, cited above. Kim did a lot of apologizing in that speech, as well he might. By August it had evidently dawned on the DPRK leadership that a big 75th anniversary Party party in October, as planned, might seem out of kilter when North Koreans had little to celebrate; with the triple-whammy of sanctions, typhoons, and flooding, along with the coronavirus (or, rather, border closures to keep it out, which have hit imports and consumer goods). Oct. 10 could hardly be forgotten, but it was repurposed with a midnight military parade—including North Korea’s largest ICBMs yet, previously unknown—and an unusual tone in Kim’s speech, full of regret that things were not better. Meanwhile attention shifted to January’s upcoming Party Congress—a fresh start, rather than looking at past glories—with an 80-day speed battle to fill the rest of 2020 and keep the masses busy.

Don’t Say Oppa! Kim Fights the Hallyu Tide

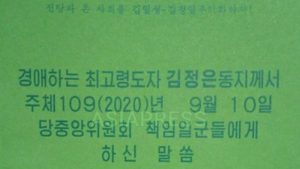

Figure 2 The cover image of the top-secret document with instructions by Kim to the WPK Central Committee. Photo: Asiapress

Kim Jong Un’s two-facedness became clear as the year ended. The Osaka-based Asiapress, which has a knack for acquiring DPRK documents, published a top secret instruction by Kim to the WPK Central Committee. Its gist, as per Asiapress’s headline at Rimjingang, its English-language website, was “Oppa is Outlawed: Top-Secret Documents Detail Kim Jong-un’s Direct Orders to Eliminate S. Korean Cultural Influence.” Mightily vexed by the spread of Southern slang among Northern youth—like calling a friend oppa, which strictly means “older brother”—Kim railed against such “perverted puppet language” and ordered its eradication. This document is dated Sept. 10: two days after Kim received Moon Jae-in’s friendly letter, and two days before his own flowery reply. Asiapress says it has more documents “which outline Kim Jong-un’s policy for inciting hatred among the domestic population towards South Korea.” That is the North’s real attitude. One can only hope his staff and the National Intelligence Service (NIS) are communicating this to Moon.

The Balloon Goes Up—No More

Back in June, North Korea’s pretext for its outrageous behavior was anger at activists who launch balloons carrying anti-regime materials into North Korea at the DMZ. Arguably this anger was confected and calculated, but some in Seoul took it seriously. Moon’s government started harassing NGOs involved with North Korea, while pledging (not for the first time) to ban balloon launches. In December it did just that, using the ruling Democratic Party (DP)’s super-majority in the National Assembly to drive through this and a raft of other legislation. The conservative opposition—the latest of whose many names is People Power Party (PPP)—resorted to a filibuster but were unable to stop it becoming law.

The balloon issue provokes strong passions. For many in South Korea and beyond, mainly but not solely on the political Right, it is a simple free speech issue—in both Koreas. Irate critics accused Moon of abetting the Kim regime in censoring independent information and keeping North Koreans captive. But there is another side, which adduces five arguments. First, South Koreans living near the DMZ dislike these activities, which create litter (many balloons fall short), discourage tourists and potentially endanger them; the North often threatens to fire at balloons, and occasionally does. Second, not all activists support the balloon launches. A few groups that do this face various accusations, ranging from the quality of their propaganda—some is obscene—to allegations of fraud. Third, there is scant evidence that anyone in North Korea has actually been moved to protest or defect by balloon-sent materials. Fourth, given the above, not only liberal but also past conservative ROK leaders, notably Park Geun-hye (2013-17), have sought to curb these activities. And fifth, as psychological warfare, sending leaflets is arguably in breach of 2018’s inter-Korean military agreement.

Figure 3 Defectors launch anti-North Korea balloons carrying leaflets near the DMZ in South Korea. Source: AFP

With activists vowing to continue balloon launches, and the border area being hard to police, it remains to be seen how the ban will fare. Meanwhile, did North Korea thank the South for making good on its promise and (some would say) doing its dirty work? Read on ….

Kim Jong Uncompromising: The Eighth WPK Congress

Though strictly speaking outside the trimester under review, the Eighth Congress of North Korea’s ruling Workers’ Party was a key event which it would be perverse not to cover. As usual the DPRK played its cards close to its chest regarding timing. This meeting was first announced in August as slated for January 2021. As noted in our last issue, that was puzzling: the next Congress was not due till May, and the harsh Northern winter was bound to be burdensome in terms of travel and logistics—not to mention the coronavirus. (North Korea still claims to be free of COVID-19, but this strains credulity.) On Dec. 30, the time narrowed to “early in January.” Delegates’ arrival in Pyongyang was reported Dec. 30; they received certificates of attendance, as did those hosted by Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il. But the actual opening of the Congress went unannounced until the first day’s session had taken place, on Jan. 5. There were some 7,000 attendees, with no social distancing and not a mask in sight.

At this writing (Jan. 12) the Congress is still in session. The main event was a marathon report by Kim Jong Un, which took nine hours to deliver spread over three days (Jan. 5-7). No full text is yet available, but KCNA has issued a summary which runs to 13,500 words in English. General comment is beyond our remit, but a two-word mini-summary might be “doubling down.” Kim’s tone was uncompromisingly hardline on all fronts. The “state-first principle” will guide domestic policy, while enemies (the US, above all) will be checked by developing a range of new WMD, including hypersonic missiles and much more. Testing times ahead.

South Korea got 700 words, reproduced as Appendix 1 below; you may care to read that first. Saying that inter-Korean relations have reverted to their pre-2018 state, Kim blamed the South, where “hostile military acts and anti-DPRK smear campaign are still going on.” The hostility alleged is twofold: new military hardware and joint exercises with the US. Both are specious. Since 2018, US-ROK maneuvers have been cut back as never before. To unilaterally demand their abolition, with no quid pro quo from Pyongyang, fails the John McEnroe test for policy: You cannot be serious.

The hardware issue is more complex. Moon’s talk and walk are not identical. If some of his words suggest an uncritical desire to embrace the North, his deeds tell a different story. While preaching peace, Moon is also quietly modernizing the ROK’s arsenal. That is only wise, since even while the DPRK paused its long-range missile launches, it stepped up testing an array of new short-range conventional weapons systems targeting South Korea. Yet Kim defended his own arms development as a matter of sovereign right; for Seoul to call this a provocation indicates “a double-dealing and biased mindset.” It is the South which “should … provide a convincing explanation for the purpose and motive in their continued introduction of cutting-edge offensive equipment.” The motive seems rather obvious. This too fails the McEnroe test.

Kim also accused the South of raising “inessential” rather than fundamental issues, citing two example. One is individual tourism, a ludicrous idea indeed, as we argued here before. But the other is “cooperation in epidemic prevention and humanitarian field” (sic). It is revealing that even in the era of COVID-19, buffeted by typhoons and needy on many fronts, Kim spurns humanitarian cooperation as inessential. To be sure, it has long been Pyongyang’s stance that North-South relations must set an overall framework before getting down to details, whereas Seoul believes starting small is the best basis for working up to bigger things. Yet despite this, in 2018 Kim was prepared to sign two wide-ranging accords presaging cooperation on many fronts. What exactly has changed? It is hard to believe now that he was sincere then.

There is more. Wagging his finger, Kim insists that a “new road … can be paved only when the south Korean authorities strictly control and root out any abnormal and anti-reunification conducts.” Not a word of acknowledgment, much less thanks, that Seoul has just taken a big step in that direction by banning balloon launches, as demanded by Pyongyang. The naïve belief in Moon’s camp that this would impress or placate the North was wishful thinking.

So it is all down to the South. Kim adds that “we do not need to show goodwill to the south Korean authorities unilaterally as we did in the past.” LOL, as they say. What goodwill? For the last two years the one-way goodwill has all come from Seoul, not Pyongyang.

Another likely reason for Kim Jong Un’s hard line is that he views Moon Jae-in as a busted flush. With just 16 months left to serve, Moon’s popularity is falling; like his predecessors, he risks becoming a lame duck as his presidency winds down so this is hardly a time for more concessions to Pyongyang. From May 2022 Kim will face a new ROK president, who might not honor his predecessors’ pledges—as in 2008, when the incoming conservative Lee Myung-bak reneged on the economic cooperation agreed by his liberal predecessor Roh Moo-hyun. This time Moon’s Democratic Party (DP) has a good chance of retaining the Blue House, so Kim’s rude rebuff may not be smart: Moon’s successor, whoever it is, is bound to be much more cautious about engaging Pyongyang. (Moon himself nobly turned the other cheek in his own New Year address; the relevant portion is reproduced as Appendix 2 below.)

Kim seems not to care. Not for the first time, his disdain is plain. One wonders if dreamers like Unification Minister Lee In-young, who on Jan. 4 confidently predicted a “positive message of dialogue and cooperation” from Pyongyang in the near future, will finally admit that North Korea is playing a different game and one-sided engagement is not working. They may not; for many middle-aged ROK leftists, “unification” is an article of faith rather than a thought-through strategy. Few younger South Koreans share such sentimentality. All told, it is hard to hold out much hope for inter-Korean relations in 2021.

Epilogue

Just as this issue of Comparative Connections went to press, Kim Yo Jong weighed in. Other than snapping at South Korea’s foreign minister in December, Kim Jong Un’s sister had been quiet lately. At the Party Congress she apparently lost her alternate Politburo membership—prompting frenzied speculation among Pyongyang-watchers. But whatever her formal rank, the First Sister is evidently still a power in the land, On Jan. 12—the same day the Congress finally closed—she issued a statement attacking South Korea for speculating whether or when Pyongyang might see a military parade: a matter still unclear at this writing. She concluded: “The southerners are a truly weird group hard to understand. They are the idiot and top the world’s list in misbehavior as they are only keen on things provoking world laughter.” Even Unification Minister Lee In-young will surely be hard put to find a silver lining there.

Appendix 1: Section of Kim Jong Un’s Report to the Eighth WPK Congress

3. For Independent Reunification of the Country and Development of External Relations

In the third part of his report, the Supreme Leader mentioned the important issues for the independent reunification of the country and development of external relations.

The report studied the issues concerning south Korea in view of the prevailing situation and the changing times and clarified our Party’s principled stand on the north-south relations.

As specified in the report, our nation is now standing on the crucial crossroads of whether to advance along the road of peace and reunification after breaking the serious deadlock in the north-south relations or to continue to suffer the pain resulting from division in the vicious cycle of confrontation and danger of war.

It is no exaggeration to say that the current inter-Korean relations have been brought back to the time before the publication of the Panmunjom Declaration and the hope for national reunification has become more distant.

Hostile military acts and anti-DPRK smear campaign are still going on in south Korea, aggravating the situation of the Korean peninsula and dimming the future of the inter-Korean relations.

Judging that the prevailing frozen north-south relations cannot thaw by the efforts of one side alone nor improve by themselves with the passage of time, the report stressed that if one sincerely aspires after the country’s peace and reunification and cares about the destiny of the nation and the future of posterity, one should not look on this grave situation with folded arms, but take proactive measures to redress and improve the present north-south relations facing a catastrophe.

The report clarified the principled stand on the inter-Korean relations as follows:

It is necessary to take stand and stance to resolve the basic problems first in the north-south relations, halt all acts hostile toward the other side and seriously approach and faithfully implement the north-south declarations.

The report pointed out the main reason why the north-south relations which had favorably developed in the past were frozen abruptly and brought back to those of confrontation.

The south Korean authorities are now giving an impression that they are concerned about the improvement of north-south relations by raising such inessential issues as cooperation in epidemic prevention and humanitarian field and individual tourism.

They are going against the implementation of the north-south agreement on guaranteeing peace and military stability on the Korean peninsula in disregard of our repeated warnings that they should stop introducing latest military hardware and joint military exercises with the US.

Worse still, they are getting more frantic about modernizing their armed forces, labelling our development of various conventional weapons, which pertains entirely to our independent rights, a “provocation.”

If they want to find fault with it, they should first give an explanation for the chief executive’s personal remarks that south Korea should accelerate its efforts for securing and developing latest military assets, that it would develop ballistic and cruise missiles with more precision and power and longer range than the existing ones, and that it had already developed ballistic missiles with the world’s heaviest warhead. They should also provide a convincing explanation for the purpose and motive in their continued introduction of cutting-edge offensive equipment.

The report seriously warned that if the south Korean authorities continue to label our action “provocation” with a double-dealing and biased mindset, we have no other option but to deal with them in a different way.

A new road toward improved north-south relations based on firm trust and reconciliation can be paved only when the south Korean authorities strictly control and root out any abnormal and anti-reunification conducts.

Whether the north-south relations can be restored and invigorated or not entirely depends on the attitude of the south Korean authorities, and they will receive as much as they have paid and tried.

The report stressed that at the present moment we do not need to show goodwill to the south Korean authorities unilaterally as we did in the past, and that we should treat them according to how they respond to our just demands and how much effort they make to fulfill the north-south agreements.

It analyzed that the north-south relations may return to a new starting point of peace and prosperity in the near future, as desired by all compatriots, as they did in the spring three years ago, depending on the south Korean authorities’ attitude.

Appendix 2: Section of President Moon Jae-in’s New Year address

Fellow Koreans,

This year marks the 30th anniversary of South and North Korea simultaneously joining the United Nations. The two Koreas should join hands and together prove that a peaceful and prosperous Korean Peninsula can also contribute to the international community. A peaceful Peninsula free of war and nuclear weapons is what we are obliged to pass down to the Korean people and posterity. The Government will strengthen the ROK-U.S. alliance in step with the launch of the Biden Administration. At the same time, we will make our final effort to achieve a major breakthrough in the stalled North Korea-U.S. talks and inter-Korean dialogue.

Inter-Korean cooperation on its own can achieve many things. Peace equals mutual benefit. We have awakened to the fact that we are closely connected with each other after suffering from infectious livestock diseases, emerging infectious diseases and natural disasters. We are in the same boat in regard to many issues. For the survival and safety of both South and North Koreans, we have to find ways to cooperate.

I hope that the process of dealing with COVID-19 will initiate mutual benefit and peace. I would like the two Koreas to participate in regional dialogues about the Northeast Asia Cooperation Initiative for Infectious Disease Control and Public Health as well as the initiative for Korea-ASEAN comprehensive healthcare cooperation. Collaboration in response to COVID-19 can expand to cooperation on issues directly connected to the safety and survival of South and North Koreans such as infectious livestock diseases and natural disasters. The broader cooperation expands, the further we can move along the path toward unification.

The key driving force of the Korean Peninsula peace process is dialogue and mutually beneficial cooperation. Our determination to meet at any time and any place and talk even in a contact-free manner remains unchanged. The two Koreas should jointly fulfill all the agreements made together to date—especially the three principles of mutual security guarantees, common prosperity and zero tolerance for war. If we can draw support from the international community in the process, the door to a community of peace, security and life will open wide, not just on the Peninsula but also in East Asia.

Sept. 1, 2020: ROK Unification Ministry (MOU) says it has requested a greater than 3% increase in its budget for inter-Korean cooperation next year, to 1.24 trillion won ($1.05 billion). Even though relations are stalled, the plan is to earmark more for hypothetical joint action against disease and natural disasters.

Sept. 1, 2020: Meeting Japan’s ambassador in Seoul, Koji Tomita, South Korea’s Unification Minister (MOU) Lee In-young asks Tokyo to support efforts to improve inter-Korean ties, claiming that this will be “very beneficial for Japan as well.”

Sept. 2, 2020: ROK National Security Adviser Suh Hoon “clarifies” that the ROK-US working group forum on North Korea is “basically … useful,” and its critics are misinformed. Seoul and Washington are consulting on how to improve it, by “adjusting the aspects of it being misunderstood and excessively functioning” (sic). (See Aug. 21 in the previous issue.)

Sept. 3, 2020: Meeting Shin Hee-yong, new head of the ROK Red Cross, MOU Lee says he hopes the two Koreas “can kick off video reunions over the Chuseok holiday” (the Korean harvest festival, this year falling on Oct. 1). This seems optimistic, as North Korea has never even accepted the video equipment which Seoul paid for—obtaining a UN sanctions waiver as long ago as March 2019. In the event, no reunions are held.

Sept. 3, 2020: At the annual Seoul Defense Dialogue (SDD), ex-USFK commander Gen. Vincent Brooks predicts that North Korea will hold off re-engaging with the South until 2021, when the election campaign for Moon Jae-in’s successor may give it more leverage.

Sept. 3, 2020: A propos another stalled project, MOU says it may redeem funds from the UN World Food Programme (WFP) if there is no progress by end-2020. In June 2019 Seoul had announced plans to send 50,000 tons of rice aid, and gave WFP $11.6 million to cover costs—but Pyongyang rejected the offer. (See also Nov. 30.)

Sept. 4, 2020: NK News reports that in late August a court in Incheon acquitted a lawyer who had brought back North Korean books and newspapers after attending a business forum held in Pyongyang in November 2018. The judge ruled that since MOU had approved his trip, the defendant could legally possess such items—otherwise banned under the National Security Law (NSL) —for personal research use.

Sept. 5, 2020: Pyongyang vows “severe punishment” for officials in Wonsan, accusing them of failing to prepare for Typhoon Maysak which struck the east coast of both Koreas on Sept. 2. An unspecified incident in the port city caused dozens of casualties.

Sept. 6, 2020: ROK Red Cross says MOU has commissioned it to create virtual reality (VR) content featuring the Northern hometowns of divided families: “As the separated families are aging rapidly and there are not enough opportunities for reunions, we decided to push ahead with this project using cutting-edge technology to offer them consolation.”

Sept. 7, 2020: MOU Lee tells a forum in Seoul that better inter-Korean ties—for instance, cooperation in public health—can move denuclearization forward and “open the era of complete, verifiable and irreversible peace, with the two Koreas taking the lead in cooperation with the international community … We hope that the North will respond to this new start.”

Sept. 14, 2020: Responding to lawmakers’ questions ahead of his confirmation hearing, Gen. Suh Wook—nominated by President Moon as Minister of National Defense (MND); hitherto he was chairman of the ROK Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS)—says that “no signs indicating imminent firings of an SLBM [submarine-launched ballistic missile] have been detected.” There is speculation that the DPRK might mark the 75th founding anniversary of its ruling Workers’ Party (WPK) on Oct. 10 with a launch of a new missile.

Sept. 16, 2020: JCS nominee Won In-choul (currently Air Force chief of staff), also replying to questions from lawmakers, opines that the North “could launch an SLBM by using catapulting devices.” It is unclear if this difference denotes a changed military assessment, or confusion. No launch occurs.

Sept. 16, 2020: On his first visit to the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) as Unification minister, Lee calls on North Korea to implement 2018’s inter-Korean accords, reopen cut communication lines, and resume “open-minded” dialogue. At Panmunjom Lee waves to DPRK soldiers. It is not shown, or stated, whether the Korean People’s Army (KPA) waved back.

Sept. 17, 2020: MOU Lee tells DMZ Forum 2020 that the two Koreas should “set up a joint disaster control system in the DMZ” to tackle inter alia “flooding, damage from blight and harmful insects [and] forest fires.” This could “also bring in people to slow-developing border regions and get the peace engine up and running if roads and railways are connected.”

Sept. 18, 2020: The day before the second anniversary of his third summit with Kim Jong Un, Moon tells Buddhist leaders: “If (we) don’t give up hope for meetings and dialogue, we will surely move on to the path of peace and unification.”

Sept. 19, 2020: Moon marks summit anniversary with a Facebook post: “Together with Chairman Kim Jong-un, I declared denuclearization and peace on the Korean Peninsula.” Since then “internal and external restraints” have stopped the peace clock, but a “seed sown in history” is sure to bear fruit. The ROK holds no official commemoration of the anniversary, which passes wholly unmentioned in DPRK media.

Sept. 20, 2020: South Korean police reveal that on Sept. 17 they caught a defector trying to go back to North Korea across the DMZ. Arrested in a military area in Chorwon in central Korea, the unnamed man in his 30s, who had come South in 2018, was found with cutters and four mobile phones.

Sept. 23, 2020: ROK Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries (MOF) says that on Sept. 21 one of its officials went missing—leaving only his shoes—from an inspection boat patrolling waters off Yeonpyeong island, near the Northern Limit Line (NLL, the de facto inter-Korean maritime border). An intensive search fails to find him. MOF adds that “according to our military intelligence, he was found in North Korean waters late Tuesday [Sept. 22]).

Sept. 23, 2020: “Sources” in the National Intelligence Service (NIS), the ROK spy agency, say the as-yet unnamed 47-year old was shot and “cremated” by KPA soldiers while trying to defect. They are probing his motives, and say there is “no evidence that any senior official is involved in this case.”

Sept. 24, 2020: ROK Ministry of National Defense (MND) “strongly condemns” what it calls “an act of brutality … According to our military’s thorough analysis of diverse intelligence,” North Korean troops found the missing official in its waters, shot him, and burnt his body. In sharp tones, MND urges Pyongyang to explain and punish those responsible. It adds that the man had financial and other problems, and was probably seeking to defect.

Sept. 24, 2020: The Blue House (Cheongwadae, the ROK presidential office and residence) condemns this “inhumane” shooting of a South Korean “who had no weapon and no intention to resist,” as an “act against international norms and humanitarianism.” President Moon, calling the incident “shocking” and intolerable, orders South Korea’s military to further strengthen its security posture. MOU weighs in similarly, adding that it has no way to communicate with the North since the latter cut all inter-Korean communication lines in June.

Sept. 25, 2020: In a most unusual message from the WPK’s United Front Department (UFD), Kim Jong Un apologizes for this “unsavory” case. The North’s explanation of why it shot the man strains credulity. Blue House also reveals that Moon and Kim exchanged fulsome letters early in May, and publishes their texts (unofficial translation here).

Sept. 27, 2020: Blue House calls for a joint probe with North Korea, and for the inter-Korean military hotline to be reopened to discuss this. Pyongyang makes no response, but its official Korean Central News Agency (KCNA)—rather than the navy or government—warns Seoul against intruding into Northern waters. KCNA adds that the North is “about” to organize its own search, and will “even consider … ways of handing over any tide-brought corpse to the south side conventionally in case we find it.”

Sept. 27, 2020: Mobilizing 39 vessels and six aircraft, ROK Navy and Coast Guard continue their search for the official’s body, despite the DPRK’s warning against intrusion. They clarify that they are staying strictly south of the NLL.

Sept. 29, 2020: “Parliamentary sources” in Seoul, evidently after intelligence briefings, say the ROK military wiretapped KPA internal communications with and about the MOF official in real time throughout his ordeal. The captain on the spot talked of rescuing him, but was overruled from above. The intel confirms that he was trying to defect.

Sept. 29, 2020: After its own investigation, ROK Coast Guard concludes that the man was seeking to defect.

Sept. 29, 2020: MOU admits it okayed an NGO plan to send medical aid to North Korea just after news of the fatal shooting. It has told all six aid organizations granted such approval in September to suspend deliveries for now.

Oct. 8, 2020: In a video address to the Korea Society in New York, President Moon suggests that the US and ROK work jointly toward a declaration formally ending the Korean War. He says trust will be built by “keeping our ears, mind and heart open toward” North Korea. Although “talks have now stalled, and we are catching our breath … we can neither allow any backtracking on hard-earned progress nor change our destination.”

Oct. 8, 2020: MOU data, requested by an opposition lawmaker, show that in quantitative terms North Korean media criticism of South Korea soared six-fold in 2019 (981 stories) compared to 2018 (152). Three outlets were surveyed: the party daily Rodong Sinmun, the official Korean Central News Agency (KCNA), and Uriminzokkiri, a propaganda website for external consumption. The 2020 total exceeds 600 items so far, with 239 in June alone but fewer than 10 per month subsequently (see Appendix 2 in our last issue).

Oct. 10, 2020: North Korea marks 75th anniversary of the founding of ruling Workers’ Party (WPK) with a big military parade: its first in two years, held unusually at midnight. Hardware rolled out includes a huge new ICBM, the world’s largest of its kind, on an 11-axle transporter erector launcher (TEL). Kim Jong Un’s emotional speech includes a “warm wish …to our dear fellow countrymen in the south, and hope … the day would come when the north and south take each other’s hand again.”

Oct. 11, 2020: Saying it is reviewing Kim’s speech, the Blue House reaffirms that inter-Korean accords should be honored “and war should be kept at any cost” (sic).

Oct. 12, 2020: After Kim’s “warm wish,” MOU voices hope for improved inter-Korean ties, but says conditions are not yet right to make specific proposals.

Oct. 13, 2020: MND assures South Koreans that the ROK can “immediately respond to and incapacitate” DPRK short-range missiles and multiple rocket launchers (MLRs) displayed at the North’s Oct. 10 parade.

Oct. 15, 2020: In his latest report on DPRK human rights, UN special rapporteur Tomas Ojea Quintana denounces Lee Dae-jun’s killing as a “violation of international human rights law” and demands that Pyongyang punish those responsible.

Oct. 19, 2020: ROK opposition lawmaker says MOU slashed its 2021 budget for the now demolished North-South liaison office to 310 million won ($270,000), from 6.41 billion won in 2020.

Oct. 21, 2020: MOU reports that just 48 North Korean defectors—23 men and 25 women—reached South Korea in the third quarter: well down from the 226 who arrived in Q3 of 2019. Travel restrictions due to COVID-19 are driving a sharp fall: there were 135 in Q1 and a mere 12 in Q2.

Oct. 21, 2020: Restating familiar themes, MOU Lee In-young tells a forum in Seoul: “We are faced with the task of moving the US-North Korea nuclear talks forward through inter-Korean trust, allowing individuals to travel to North Korea and reconnecting and modernizing railways and roads as agreed upon by the leaders of the two Koreas … That is the way to go no matter what and the responsibility that cannot be neglected.”

Oct. 23, 2020: Shin Hee-young, newish head of the ROK Red Cross, suggests that instead of one-sided aid which hurts the DPRK’s pride, the two Koreas conduct joint medical research.

Oct. 27, 2020: MOU says it will conduct an ecological survey of the Han River estuary next month. In 2018 the two Koreas carried out a joint survey, but this time the ROK will stick to the South side of the river only.

Oct. 29, 2020: Without naming him, KCNA attacks ROK national security adviser Suh Hoon for acting “so sordidly” on “his recent secret junket” to Washington. Suh’s saying that inter-Korean ties also require consultation with other countries, such as the US, shows “the south Korean authorities’ wanton denial, perfidy to and an open mockery of” all past North-South agreements, which put national independence above all. Calling Suh “an American poodle,” KCNA adds: “We can not but doubt his sanity.”

Oct. 30, 2020: In a 1,000 word KCNA commentary clearly meant to draw a line, Pyongyang again expresses “regret” at “the inglorious incident”—but blames Seoul for not controlling its citizen, and slams Southern conservatives for “working with bloodshot eyes to slander their fellow countrymen in the north.” The piece is headlined: “Sustained Confrontational Frenzy of S. Korean Conservative Forces May Invite Greater Misfortune.”

Oct. 30, 2020: At a forum in Cheorwon near the DMZ, MOU Lee calls the two Koreas “a single community of life and security.” He avers: “Once the South and the North join hands, the DMZ could be turned into [an] experimental space of coexistence where the possibility of peace and prosperity on the Korean Peninsula can be tested in advance.”

Nov. 9, 2020: Following the US presidential election, MOU Lee urges North Korea to “take a discreet, wise, and flexible approach” during the transition and refrain from provocations.

Nov. 10, 2020: ROK provincial authorities in Gangwon—the only Korean province bisected by the DMZ—reveal that in August they sent a letter inviting DPRK counterparts to co-host the 2024 Winter Youth Olympics. They live in hope, though no reply has been received.

Nov. 19, 2020: With winter coming, MND says it will wrap up this year’s work excavating remains at Arrowhead Ridge, a Korean War battlefield. This was meant to be a joint effort, but North Korea remains unresponsive. The South will resume work in the spring.

Nov. 20, 2020: MOU Lee reiterates call for the two Koreas to cooperate on COVID-19: “When vaccines and treatment … are developed … in the near future, a new environment will be created in the Korean Peninsula in which people and goods can come and go.”

Nov. 23, 2020: On the 10th anniversary of North Korea’s shelling of Yeonpyeong island, which killed four, South Korean Defense Minister Suh Wook pays tribute to the fallen and vows a strong defense posture: “True peace needs to be supported by strong power.” The same day, MOU Lee tells officials of major chaebol (conglomerates) including Samsung, Hyundai Motor, SK and LG, whose heads accompanied President Moon to Pyongyang in 2018, to be prepared: an inter-Korean breakthrough “may come sooner than expected.”

Nov. 24, 2020: Korea Herald reports that on Nov. 4, a DPRK defector in his 20s arrived undetected across the DMZ near the east coast. A former gymnast, the man said he vaulted over fences 3 meters (10 feet) high. ROK authorities make him jump twice to prove it.

Nov. 25, 2020: Park Sang-hak, leader of Fighters for a Free North Korea, is charged with assaulting a broadcasting team who visited his home (uninvited) to interview him about his leafleting campaign. He allegedly beat and threw bricks at the journalists, and fired a tear gas gun at police. Park counter-claimed that the journalists were housebreaking.

Nov. 26, 2020: MOU Lee says South Korea should send the North food and fertilizer next spring, when it faces a risk of “extreme famine.” And yet …

Nov. 30, 2020: In a saga going back to June 2019, MOU says it is in talks with the UN World Food Programme (WFP) to get back $11.6 million it had sent to supply 50,000 tons of rice to North Korea. Pyongyang rejected Seoul’s offer. (See also Sept. 3.)

Dec. 5, 2020: At the International Institute of Strategic Studies (IISS) Manama Dialogue in Bahrain, ROK Foreign Minister Kang Kyung-hwa says it is hard to believe the DPRK’s claim to be free of COVID-19: “All signs are that [they are] very intensely focused on controlling the disease that they say they don’t have.” This is not part of her prepared remarks.

Dec. 8, 2020: Ever optimistic, Unification Minister Lee detects a “U-turn” toward a thaw since June’s tensions. He says North Korea may respond to the South’s offers of cooperation on COVID-29 after its upcoming Party Congress.

Dec. 9, 2020: Ji Seong-ho, one of two DPRK defectors elected in April as a lawmaker for the ROK conservative opposition (named the People Power Party, or PPP), says that seeking nuclear talks with North Korea without addressing its human rights issue is “quite a hollow thing, such as a sand castle.”

Dec. 14, 2020: By 187 votes to 0, ROK National Assembly approves a revision to the National Intelligence Service Korea Act. The spy agency can no longer investigate alleged pro-North activities by South Koreans: this power, abused in the past, now passes to the police. The conservative opposition PPP boycotts the vote after its filibuster the day before is overruled—as the ruling Democratic Party (DP) can do after 24 hours, having over 180 seats.

Dec. 14, 2020: By the same 187-0 margin, the National Assembly passes a revision to the Development of Inter-Korean Relations Act, to ban sending leaflets into North Korea. Maximum penalties are three years jail or a fine of 30 million won ($27,000). Again the PPP boycotts the vote after its filibuster is overruled.

Dec. 15, 2020: One of the most high-profile (and controversial) balloon-launching activists, Park San-hang of Fighters for a Free North Korea, says he is contemplating a constitutional challenge to the ban on sending leaflets.

Dec. 17, 2020: MOU expresses regret that Tomas Ojea Quintana, UN special rapporteur on human rights in the DPRK, has called on Seoul to reconsider the leaflet ban.

Dec. 17, 2020: South Korea says it is developing ground vibration sensors to better detect movement near the DMZ, after a defector jumped over fences without raising alarms.

Dec. 24, 2020: MOU says it is drafting guidelines on the new ban on sending leaflets into North Korea, to clarify its scope of application.

Dec. 25, 2020: The Sejong Institute, a private think-tank in Seoul, reports that Kim Jong Un made 51 public appearances this year: the fewest ever in his nine-year reign, down from 85 in 2019 and 212 in 2013. Fourteen were economy-related, 12 military, and 25 political. Eight were on-site inspections, mostly related to natural disasters or health issues. The Institute speculates that COVID-19 is the main reason for Kim’s relative invisibility of late.

Dec. 28, 2020: Statistics Korea, South Korea’s official statistical agency, publishes a raft of economic data and estimates on the North Korean economy in 2019. This includes a number of inter-Korean comparisons.

Dec. 29, 2020: The Asan Institute for Policy Studies, a private think-tank in Seoul, predicts that North Korea may greet President Biden with a missile test: “the North will consider playing the card of an ICBM launch in a desperate measure to break the deadlock.”

Dec. 29, 2020: Almost 30 South Korean human-rights organizations file a constitutional challenge to the new anti-leafleting law.

Dec. 29, 2020: Launching the Northeast Asia Conference on Health Security, an initiative of Moon’s, FM Kang expresses hope that North Korea might join. The inaugural virtual meeting comprises South Korea, the United States, China, Japan, Russia, and Mongolia.

Dec. 30, 2020: A Politburo meeting—the 22nd session of the Political Bureau of the Seventh Central Committee of the WPK—reviews preparations for the upcoming Eighth Congress, set for “early in January” (still no exact date). Interestingly, this is chaired not by Kim Jong Un (though he attends) but former Premier Kim Jae Ryong, under KJU’s “guidance.”

Dec. 30, 2020: DPRK’s Voice of Korea reports: “Delegates to the Eighth Party Congress arrived in Pyongyang in late December.”

Dec. 31, 2020: A joint survey of 414 defectors by two organizations, the Database Center for North Korean Human Rights (NKDB) and NK Social Research (NKSR), finds that 26.6% of them sent money to North Korea this year. Remittances averaged 1.51 million won ($1,390), with on average 1.8 transactions in 2020. A larger number, 38.6%, said they maintained contact with family in the North, nearly all (91.6%) by phone. Over one in seven (14.8%) said they had considered returning to North Korea.

Dec. 31, 2020: MOU says that from Jan. 4 it will increase support for NGOs aiding North Korea. Henceforth they can apply three times a year, rather than once, and need cover only 30% of financing themselves, down from 50%. Whether Pyongyang will accept such assistance is another matter.

Dec. 31, 2020: Former UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon calls on South Korea to “rectify” its ban on sending leaflets into North Korea: “I cannot help but feel miserable that our country is facing criticism from home and abroad due to the human rights issue.”

Jan. 1, 2021: Although North Korea cut all inter-Korean communication links in June, the United Nations Command (UNC) confirms that its direct telephone line at Panmunjom to the KPA remains operational. It delivered 86 messages in 2020, plus line checks twice daily.

Jan. 1, 2021: Instead of Kim Jong Un’s customary substantial New Year address, DPRK media carry a very short handwritten letter. Kim offers greetings, thanks people for their trust in “difficult times,” and promises to “work hard to bring earlier the new era in which the ideals and desires of our people will come true.”

Jan. 4, 2021: In his New Year address, MOU Lee says Seoul is expecting a “positive message of dialogue and cooperation” from Pyongyang in the near future.

Jan. 4, 2021: Osaka-based media NGO Asiapress publishes what it claims is a secret document from September in which Kim Jong Un launches a campaign to extirpate ROK linguistic usages as part of a “policy for inciting hatred among the domestic population towards South Korea.” Asiapress says it has more DPRK documents in this vein.

Jan. 6, 2021: Congress continues, and so does Kim Jong Un’s report.

Jan. 7, 2021: Congress continues. Kim Jong Un concludes his report.

Jan. 8, 2021: Reuters reports that ROK prosecutors have indicted Kim Ryen Hi for violating the National Security Law (NSL). Kim, a North Korean woman aged 51 who claims she was tricked into defecting, has kept trying to be sent back to the DPRK, including turning herself in as a spy. Her lawyer comments: “It would invite international ridicule if you charge someone who is only fighting to go back home with threatening national security for sharing her daughter’s letters on Facebook.”

Jan. 9, 2021: Rodong Sinmun, the WPK daily, publishes a 13,500 word summary (not the full text) of Kim’s nine-hour speech to the Eighth Congress. This is hardline on all fronts, including toward South Korea.

Jan. 9, 2021: Reacting (if hardly responding) to Kim Jong Un’s diatribe, MOU reiterates South Korea’s commitment to implementing inter-Korean agreements.

Jan. 11, 2021: In his New Year address, Moon repeats call for the two Koreas to work together: “Our determination to meet at any time and any place and talk even in a contact-free manner remains unchanged. The two Koreas should jointly fulfill all the agreements made together to date.”

Jan. 13, 2021: DPRK media publish a statement by Kim Jong Un’s sister Kim Yo Jong, attacking speculation in Seoul about the North holding a military parade. She concludes: “The southerners are a truly weird group hard to understand. They are the idiot and top the world’s list in misbehavior as they are only keen on things provoking world laughter.”