Articles

Australia closed its borders to confront COVID-19 and rode out recession, while China shut off key markets to punish Australia. The short recession caused by pandemic ended Australia’s record run of nearly three decades of continuous economic growth; Beijing’s coercion crunched the optimism of three decades of economic enmeshment. However, Australia’s economy rebounded while the China crunch continues, causing Australia to question its status as the most China-dependent economy in the developed world. The Canberra-Beijing iciness has built over five years, marking the lowest period since the establishment of diplomatic relations in 1972. In 2021, the language of “strategic partnership” died and the “strategic economic dialogue” was suspended by China. The Biden administration promised not to abandon Australia, saying that US-China relations would not improve while an ally faced coercion. Australia embraced Washington’s assurance, along with the elevation of the Quad with the US, Japan, and India.

Fighting COVID-19

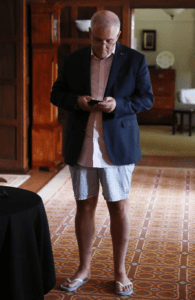

Figure 1 Summit-wear in the pandemic age—doing 14 days quarantine after his 2020 visit to Japan, Scott Morrison prepares to take part in a (virtual) G7 summit—with the camera showing only his top half. Photo: Scott Morrison/Instagram

At the end of August 2021, COVID-19 had caused 1,006 deaths in Australia, but the country has closed its international borders. The only people allowed to enter Australia are citizens, permanent residents, New Zealanders, and those who gain exemption under categories for seasonal workers or business. Anyone arriving in Australia must quarantine for 14 days (even if vaccinated). All overseas travel from Australia is banned (except to New Zealand). Since the border was closed in March 2020, anyone seeking to leave the country must get a government “exemption” by showing “exceptional circumstances” and a “compelling reason.” The number of people allowed to enter the country each week was capped at 6,000 people; then in July 2021, the weekly cap was halved to 3,000 people.

Closing down the country in 2020 closed down the economy, bringing on the first recession since 1991. Yet the recovery was swift. In the darkest days of 2020, Australia’s Treasury feared that unemployment would reach 15% and the economy would contract by 20%. Instead, employment has gone back to pre-pandemic levels and by the middle of 2021 the jobless rate was 5.6%. Remarkably, Australia’s economy did not shrink in the 2020-21 financial year—instead GDP grew by 1.4%. Still, the cost of the government’s response to COVID is a massive blowout in the federal budget deficit. In the 2021 budget, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg said net debt will increase to A$617.5 billion (US$459.9 billion, or 30% of Australia’s GDP) this year and is projected to peak at A$980 billion (40% of GDP) by mid-2025. Among the ifs-and-maybes of those projections is how much longer China will pursue its campaign of coercion expressed as trade punishment.

The China Chill and Economic Sanctions

Australia’s icy relations with China are in their fifth year. Previous cold spells—under the Hawke, Howard, and Rudd governments—were short because economic interests quickly rekindled relations. Today’s iciness delivers frigid diplomacy, chilled strategic perspectives, and economic frostbite for Australian exporters. Beijing isn’t taking calls from Australian ministers. No senior Chinese leader has come to Australia since March 2017.

As promised by the ambassador, the “coercive diplomacy” weapons China has honed around the world were deployed. Beijing used tariffs, duties, inspections, quarantine, and port go-slows to target Australian agriculture, coal, copper, wine, university education, and tourism. Australia’s ambassador to Beijing, Graham Fletcher, said China “has been exposed as quite unreliable as a trading partner and even vindictive.” The statistical roundup of 2020 by the journal Australian Foreign Affairs estimated the cost of Chinese sanctions at A$19.4 billion, on Australian exports worth A$153.2 billion in 2018-19. The trade and investment timeline created by the Australia-China Relations Institute recorded the extent of China’s coercive tactics.

By the end of 2020, the total value of trade between the two countries had fallen by 2% from the previous year. Only China’s huge appetite for Australia’s iron ore, and its surging price, sustained the trade figures. Taking iron ore out of the equation meant that at the end of 2020, Beijing had cut the value of the Australian trade in other industries by 40%. In 2021, however, iron ore kept delivering for Australia—China had no ready alternatives.

The director of Sydney’s Australia-China Relations Institute, James Laurenceson, said “of the dozen or so Australian goods that China did close its market to, many could be diverted elsewhere.” Global markets had taken the sting out of China’s economic punishment. Laurenceson cautioned that China’s demand for iron ore is likely to fall as steel production is forecast to peak in the mid-2020s. One potential game-changer is China’s effort to get access “to the world’s largest reserve of untapped high-quality iron ore” in the Simandou range in Guinea in West Africa.

China’s commentary has become explicit about the political and diplomatic purposes of the trade sanctions. The repeated line from China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs is that it’s up to Australia to correct its errors. The errors were catalogued in November 2020, when Chinese diplomats in Canberra handed a list of 14 grievances to a journalist. The rap sheet claims it’s all Australia’s fault for being “opaque” and “doing the bidding of the US”; for “politicization and stigmatization” of China; “spearheading the crusade against China”; and “poisoning the atmosphere of bilateral relations.” Brush off the bombast to view a useful list of choices Australia could not and would not recant on: banning Huawei from its 5G network; foreign interference laws to restrict Chinese interference in Australian politics; calling for an inquiry into the origins of COVID-19; and criticism of Chinese actions in Xinjiang, Hong Kong, the South China Sea, and its menacing of Taiwan.

The 14 points offer a Rosetta Stone for reading the psychology of Xi Jinping’s regime and the Chinese Communist Party, according to Peter Hartcher, the international editor of The Sydney Morning Herald and Melbourne’s Age. In his 2021 book Red Zone: China’s Challenge and Australia’s Future, Hartcher said the demands break into three sections. The first four relate to Beijing’s efforts to influence or control, the demand “to be given more power over Australia.” The next four points expose “Just as [Beijing] cannot abide the least criticism at home, it cannot tolerate criticism abroad.” The remaining six points “reveal the brittleness of Beijing’s self-image and self-confidence.”

The Biden administration says it has told Beijing that any improvement in US-China relations will be linked to an end of sanctions against Australia. The president and the administration had made clear that the US would back Australia, National Security Coordinator for the Indo-Pacific Kurt Campbell has said. The Biden administration’s “Asia Tsar” said Australia’s response to China’s coercion had answered the question of whether Canberra’s alignment could swing from Washington to Beijing.

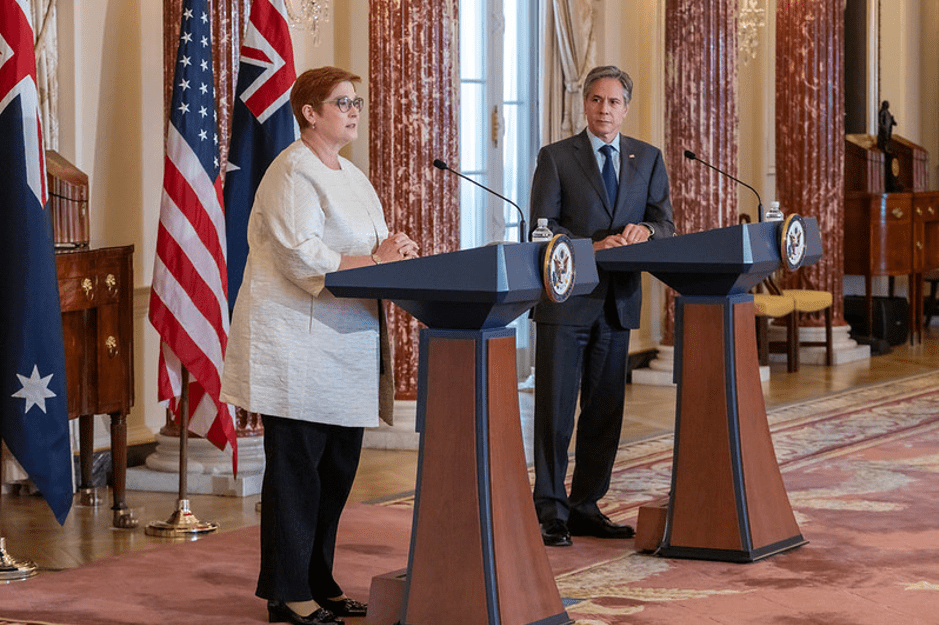

Campbell doubted that Beijing could reset its strategy toward Australia. Australia was responding “quietly and carefully,” Campbell said, but he predicted continuing Chinese assertiveness. The stand-with-Australia message was repeated in talks in Washington between Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Foreign Minister Marise Payne. Blinken said the US would not leave Australia alone on the field “in the face of economic coercion by China.” Payne said Australia had been clear about “a number of challenges” it faced from China. “We welcome the clear expressions of support from Washington as Australia works through those differences. It is hard to think of a truer expression of friendship,” Payne said.

Australia Rethinks China—The Perils of Partnership

Government-level casualties of the chill include the burial of the Australia-China “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership” and death of the “Strategic Economic Dialogue.” In 2013, under Prime Minister Julia Gillard, Canberra signed up to “strategic partnership” as Beijing’s price for getting an annual leaders’ summit. In a speech in February 2021, Scott Morrison bid adieu to the idea of strategic partnership.

In May 2021, China suspended the China-Australia Strategic Economic Dialogue. Announcing the action, China’sNational Development and Reform Commission said Australia had “launched a series of measures to disrupt the normal exchanges and cooperation between China and Australia out of Cold War mindset and ideological discrimination.” Beijing’s action was interpreted as retaliation for Canberra’s announcement that it was tearing up Belt and Road agreements between China and the state of Victoria. The “annual” economic dialogue had not been held since 2017, so China was suspending an already lifeless mechanism.

To the squeeze on business and the freeze on government contact, add the human dimension of an Australian journalist taken as hostage and now charged. On Aug. 14, 2020, Australia was informed of the detention of Cheng Lei, an Australian citizen who is a “high-profile, respected business journalist” for the state-controlled China Global Television Network. China announced that Cheng was suspected of criminal activity endangering China’s national security. After six months in detention Cheng was formally arrested in February. The Chinese authorities told Australia that Cheng was arrested on suspicion of illegally supplying state secrets overseas. In August 2021, Foreign Minister Payne issued a statement marking the fact that Cheng had been detained for one year.

China also put the squeeze on the two remaining correspondents in China working for Australian media. In September 2020, China’s Ministry of State Security interviewed Bill Birtles of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, based in Beijing, and Michael Smith of The Australian Financial Review, based in Shanghai. Told they were persons of interest in the case of the detained Cheng Lei, Birtles and Smith were banned from leaving the country. Both immediately shifted to Australian diplomatic premises while an exit deal was negotiated. After a five-day standoff, the two correspondents were allowed to return immediately to Australia. For the first time since 1973, Australian media have no correspondents in China. The state of the relationship means it’s not safe for correspondents to return to China.

Australian public opinion has tracked the growing sense of perils in the partnership. The Lowy Institute poll of how Australians view the world showed that trust, warmth, and confidence in China and China’s leaders started to decline in 2017. The 2021 survey was another record low for Australians’ views of China: “In a conspicuous shift, the majority of Australians (63%) now see China as ‘more of a security threat to Australia.” This is a substantial 22-point increase from 2020.

In the past, China could always rely on vocal support from Australian businesses. No longer. The shift in thinking is shown by the Australian Industry Group, which represents 60,000 businesses. The lobby group’s chief executive is Innes Willox, who in an article headlined “We must not trade principles in stand against Beijing bully” in the Jan. 17 edition of The Australian, said Australian business and government must “stay strong and true to our core beliefs” while continuing to talk and trade where possible.

Figure 2 US Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken with Foreign Minister Marise Payne in Washington on May 13, 2021. Photo: State Department/Ron Przysucha/Public Domain

The Australian government’s A$200 billion sovereign wealth fund, the Future Fund, has pared back its investments in China because of the tensions. The fund’s chairman, Peter Costello, said the government did not instruct the fund to sell down its China investments, and instead the fund had responded to trade sanctions against Australia. In Parliament, the Labor Opposition backs the Morrison government in facing China. Labor’s criticism is on tactics and competence, not the nature of the choice. All the attack lines in Opposition Leader Anthony Albanese’s start-of-the-year foreign policy speech in 2021 were about how badly Morrison had handled Donald Trump, not about dealing with China. Albanese said Australia should stand with the new Biden administration to both challenge and coexist with China. The idea of drawing firmer lines has become an explicit goal of Canberra’s political consensus, embraced by both the Labor and Liberal parties.

Quad 2.0 and Australia’s Quasi-alliance with Japan

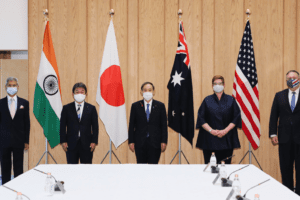

Figure 3 Foreign ministers from Japan, the US, Australia and India with Japan’s Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga at the Quad ministerial meeting in Tokyo, 6 October 2020. Photo: Kantei/Twitter

The Quad and Australia’s quasi alliance with Japan both notched seminal moments over the past year. The Quad had its first summit in March 2021, and Abe Shinzo departed as Japan’s longest-serving leader in September 2020. The first leaders’ meeting of Australia, India, Japan, and the US was a sparkling moment for Abe’s “democratic security diamond.” Australia will now find out how much its “small a” alliance with Japan was based on Abe and how much on more permanent shifts in Japan’s policy personality. The “special relationship” Abe built with Australia was atypical in the region—a level of strategic cooperation that no other Asian leader has reached for. Australia valued Abe’s declaration that Japan will have a military and security role in Asia’s future.

Abe’s influence touched much that matters in Canberra:

- Japan has risen to become a defense partner for Australia on par with New Zealand and Britain.

- In Abe’s first term as prime minister, he signed the joint declaration on security cooperation with John Howard in March 2007.

- Japan and Australia were the first countries to place theIndo-Pacific atop their foreign policies in a new regional construct.

- The trilateral (Australia, Japan, and the US) has been strengthened, making the linkage between the US–Japan and US–Australia alliances.

- Australia pondered buying its new submarine from Japan as a crowning expression of the “small-a” alliance.

Back in 2006, one of the greats of Australian strategy, Des Ball, rated Japan as Australia’s fourth most important security partner, saying Australia’s security cooperation had intensified and expanded to the point where Japan ranked behind only the US, UK, and New Zealand. And Ball was writing before Abe really got going. Today, Japan sits on that second tier. The second rung position is a long way from the US alliance, but that’s another reality separately shared by Australia and Japan—the defining importance, for each, of the US. Australia’s small “a” alliance doesn’t involve a treaty-level commitment like the US-Japan and US-Australia alliances, but it’s a relationship that shadows those pacts, based on shared interests and growing military and intelligence cooperation. A fresh element—both complicated and contentious—is the idea of Japan joining the Five Eyes intelligence club.

Abe was Asia’s pre-eminent Trump whisperer, setting the model for lavishing Trump with love to deal with a less predictable and less reliable US president. Australia’s prime minister from 2015 to 2018, Malcolm Turnbull, boasted he was tougher than Abe and got a better result with Trump. But an Australian prime minister used a Japanese prime minister to shape his approach to a US president. When Abe stepped down, Scott Morrison quickly headed to Tokyo in November 2020, to become the first world leader to meet new Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide. Because of the pandemic, Morrison’s two days in Tokyo meant he had to quarantine for two weeks on his return to Australia and participate in Parliament via a video link. Morrison and Suga announced an in-principle agreement on a Reciprocal Access Agreement (RAA) to enable Australia and Japan to streamline the stationing of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) in Japan and the Japan Self-Defense Forces (SDF) in Australia. The RAA is the second such agreement Japan has signed, following its 1960 Status of Forces Agreement with the United States. Morrison called the agreement a “pivotal moment in the history of Japan-Australia ties,” opening a “new chapter of advanced defence cooperation between our two countries.”

Figure 4 The Quad leaders’ summit— meeting virtually across time zones and the Indo-Pacific. Photo: Yoshihide Suga/Twitter

Ahead of Morrison’s visit to Japan, Foreign Minister Payne headed to Tokyo in October 2020, for a meeting of Quad foreign ministers (and also did 14-day quarantine on return). Payne’s Quad message from Tokyo was crisp. Lots of China content without using the “C-word.” Because there was no Quad communiqué, each foreign minister gave their own summation. Payne delivered six paragraphs, starting with COVID-19, then turned to the Indo-Pacific’s shaky strategic environment: “Pressure on the rules, norms and institutions that underpin stability has the potential to undermine recovery.” Looking at but not mentioning China, she noted it’s “vital that states work to ease tensions and avoid exacerbating long-standing disputes, work to counter disinformation, and refrain from malicious cyberspace activity.” And she repeated previous AUSMIN language that “states cannot assert maritime claims that are inconsistent with international law.”

Four disparate democracies can do much together, not least to reassure Southeast Asia that it has agency and options (Quad leader-speak: “strong support for ASEAN’s unity and centrality”). The anchor image responds to a permanent reality: China will always be in Asia, while the US presence is always a choice Washington makes. In choosing the Quad, the US is renewing its promise to the Indo-Pacific as much as it is joining with three fellow democracies. The Quad is not an alliance. The Indo-Pacific democratic diamond will not match the four-pointed NATO star. The outlook of the Quad members is as different as their democracies. Yet as diamonds are formed by high temperature and pressure, so the Quad bonds four democratic powers that feel the force and weight of Asia’s coming power.

The Rudd Labor government walked away from Quad 1.0 in 2008 because it had high hopes about China and doubts about Japan and India; Canberra bet on Beijing rather than Tokyo and New Delhi. Now the race has changed dramatically, the stakes are even higher, and Australia puts new wagers on Japan and India to reinforce its traditional bet on the US. Quad 2.0 arrived, Rudd notes, because Xi Jinping has “fundamentally altered the landscape” by projecting Chinese power, and strategic circumstances have “changed profoundly.” In August 2021, Rudd wrote that Beijing had underestimated the effect of its own actions on Quad solidarity. The Quad alarms China, Rudd judged, because its success poses a major threat to Beijing’s ambitions.

The “Economic Realm”

The Australian relationship with the US has a more complex and demanding economic dimension. The strategic purposes of the alliance embrace technologies and economic interdependence as key parts of the new great power competition. Once trade and the international economic system were implicit or assumed parts of the alliance. Now the many elements of China’s rise and the shock of the Trump administration mean that geoeconomics steps up beside the geopolitics. Scott Morrison says that “unlike the Cold War, geostrategic competition in the coming decades will be engaged in the economic realm. Our recent experience with economic coercion underlines that.”

Coerced by China, Australia turns to its ally in these new dimensions. The prime minister says bilateral strategic cooperation with the US must extend to economic matters: “We should consider a regular Strategic Economic Dialogue between our most senior key economic and trade officials.” Such a Strategic Economic Dialogue with Washington would focus on the China challenge, identifying and responding to coercion, supply chain protection, emerging technologies, US–Australia trade issues, and both buttressing and reforming the global system—from the nature of the World Trade Organization to guaranteeing availability of rare earths. Morrison says Australia’s 16-year-old free trade agreement with the US is “critical infrastructure” that must be upgraded. And then a strategic economic dialogue could deal with what the prime minister calls “the hard stuff,” as Morrison outlined in an address to the Australia-American Leadership Dialogue. “We’ve got to deal with the reform of the World Trade Organization,” Morrison said. “We’ve got to deal with ensuring that there is a working appellate system that ensures that the rules of trade work … to ensure that no country, no country suffers any exploitation against its interests, as we are seeing at present.”

Whatever China’s sins, it was the Trump administration that swung a wrecking ball through the WTO appellate system. Morrison has several times discussed parallels between today’s era and the 1930s. Unstated in Morrison’s 1930s comparison is the reference to a time of revisionist powers but also a protectionist-isolationist US. Standing with the US, Morrison says Australia’s “interests are inextricably linked to an open, inclusive and resilient Indo-Pacific” and to a “strategic balance in the region that favours freedom.” He nominates five areas for Australian advocacy and agency:

- Supporting open societies, open economies and our rules-based order;

- Building sovereign capacity, capability, and resilience;

- Cooperating on global challenges;

- Enabling renewed business-led growth and development, and

- Demonstrating that liberal democracies work.

Different elements in those talking points would work differently for the Trump and Biden administrations, but a unifying thought is the role of Australia’s relationship with the US. Labor’s analysis, from opposition, chimes with much of the government’s thinking on the economic realm. Labor leader Anthony Albanese has told Parliament that the US had been a core economic partner of Australia, and its importance continued to grow.

Figure 5 Scott Morrison getting used to the G7 stage. Photo: G7 Cornwall

For the third time, Morrison attended the G7-Plus dialogue, taking part in the 2021 summit in Britain, with a seat at three G7 sessions on health, the economy, and climate. Morrison’s first meeting with President Biden on June 12 turned from a bilateral to a trilateral when joined by the G7 host, Britain’s Boris Johnson. A statement from the three leaders said they discussed “issues of mutual concern, including the Indo-Pacific region.” Added to the alliance, Australia can look to work with the US in an array of institutions with a global span: the G20, the G7-Plus, President Biden’s virtual Summit for Democracy in December, the Five Eyes intelligence club; and in the Indo-Pacific through APEC, the East Asia Summit, the ASEAN Regional Forum, and the Quad. The gap in the lineup is the absence of the US in Asia’s new trade architecture.

An irony of Beijing’s coercive campaign is that on Nov. 15, 2020, Australia and China were signing what boosters call the most important ever regional trade agreement, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. What began as a tidying-up exercise for ASEAN, to join all its various treaties, greatly serves China’s interests, and China-centric supply chains. RCEP is a joining-together counter to the decoupling duel between the United States and China, and the decoupling imposed by Chinese sanctions on Australia.

The gap on the RCEP stage was India, which pulled out. The US is the ghost at the feast. Asia now has two big regional trade pacts that do not include the US—RCEP and the rebadged Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). TPP is a US-created vision of Asia’s economic future that Donald Trump abandoned. Neither China nor the US is in the TPP, salvaged by Abe with plenty of help from Turnbull. To make up for the US defection, they added extra fizz and flavor to the title, making it also a “Comprehensive and Progressive” agreement, but to merit the comprehensive tag, the CPTPP needs more players. An excellent assessment of prospective members is offered by Hayley Channer and Jeffrey Wilson: South Korea is the favorite, a comeback by the US is a “game-changer,” Britain is a “swooper,” and China and Taiwan are the “dark horses.”

Biden is a fresh jockey but domestic weight means this is a race the US will struggle to rejoin, much less win. China would have to grapple with the CPTPP’s tougher stance on tariffs and labor standards, and make major changes to the role of state-owned enterprises. Australia has welcomed China’s CPTPP interest, not least because such negotiations would require Beijing to relax sanctions and take its hands off Australia’s throat. The old order fades when Asia can even contemplate having China at the center of its two big trade deals, with the US on the outside of both. That’s not the decoupled world that Washington or Canberra wants. And it is in the economic realm where Washington must make up much ground: as Campbell comments, “For the US to be effective in Asia we are going to have to make clear we have an economic plan.”

Australian analysis goes to the same point. The “weakest aspect” of the Biden administration’s approach to the Indo-Pacific is its failure to develop a comprehensive strategy for economic engagement, according to Australia’s United States Studies Centre. The Sydney-based center issued a report in August on how the Biden administration should compete for influence. The Biden approach to China concentrated on the domestic and global arenas, rather than on influence within the Indo-Pacific, and the focus on long-term systems competition with China overlooked the urgency of near-term competition in the Indo-Pacific: “The Biden administration, like its predecessors, lacks an economic strategy for the Indo-Pacific region. This major weakness in regional policy is driven by US protectionist trade preferences at home. Proposed initiatives on digital trade and infrastructure cannot compensate for the absence of a comprehensive trade-based economic approach.”

Trying Times Try the US Alliance

Tough times raise the importance of the alliance, but the times raise questions about how tough the alliance can be. Bilaterally, Trump was good to Australia and the alliance fared well. But Trump ushered into view a US that is protectionist and mercantilist, skeptical of alliances, and more interested in deals than democracy. Much Australian discussion of the China challenge is actually about US choices, about how trying times will try the alliance. Biden’s election prompted statements to Parliament by Australia’s prime minister and opposition leader. Few other elections around the world merit such formal attention in the House of Representatives.

The prime minister avoided any mention of Biden’s stance on climate change, an issue that deeply divides his government coalition. Politically, it was far easier for Albanese, the opposition leader, to voice Labor’s support: “We are pleased that our great friend and ally will be guided by a president who not only has accepted the reality of climate change but also is ready to pursue new industries and jobs of the future.” A Biden administration commitment to net zero emissions by 2050is a key difference with the Morrison government. Ahead of Biden’s climate summit in April 2021, a senior US official briefed journalists that Australia’s greenhouse gases strategy was unsustainable: “At the moment I think our colleagues in Australia recognize there is going to have to be a shift.”

Fudging the 2050 deadline, Morrison says his focus is on “how” to get to zero, not “when.” The prime minister told the US climate summit: “Our goal is to get there as soon as we possibly can, through technology that enables and transforms our industries, not taxes that eliminate them and the jobs and livelihoods they support and create, especially in our regions.” Morrison says Australia will “preferably” reach the net zero target by 2050. The “preferably” mantra of exposes Australia to much international pushing and pressure ahead of the November meeting of the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26). Climate change was one of the topics in the first telephone conversation between Biden and Morrison on Feb. 3.

In welcoming Biden’s election in November 2020, Morrison commented on that broadening during the four years of Trump, with “new areas of cooperation in space, critical minerals, frontier technologies and more.” The down-to-earth nature of the alliance is such that it now embraces rare earths, while horizons go to outer space—in May, the Australian Defence Force announced the creation of a Space division involving the commitment A$7 billion over a decade.

The Alliance and Northern Australia

Canberra increasingly thinks about defense of northern Australia as part of the regular work of the military partnership with the US. The annual US Marine deployment to Darwin has marked its first decade, with the 10th rotation in 2021 involving 2,200 US personnel. From April to October, a US Marine Rotational Force deploys to the Northern Territory to train for expeditionary operations, enhance US–Australian interoperability and demonstrate the strength of the alliance, conduct regional engagement and enhance regional security; prepare for crisis and contingency response; among other things.

At the 2020 Australia–US Ministerial meeting (AUSMIN), the US and Australia signed a statement of principles on alliance cooperation and force posture priorities in the Indo-Pacific for the next decade. The US will fund a strategic military fuel reserve in Darwin. Discussions began on expanding the US–Australia joint training exercises in northern Australia “to include additional partners and allies to bolster regional relationships and capabilities.” Australia is used to hosting US intelligence and signals bases. Now US military facilities are being created on Australian soil. While the troops rotate through Darwin, the permanent facilities are put in place.

For the first time since World War II, US troops are spending extended periods based and training in Australia each year. The rough, tough, and lengthy US-Australia negotiations over who would pay for marine facilities in Darwin was one sign of the mental adjustments involved. Whatever Canberra anticipates, an increase in US forces based in Australia gets a negative popular response. A survey in July 2021 found just 15% of Australians say that “closer co-operation with the United States” is better for the national interests than the status quo, preferred by 47%. Only 18% of Australians preferred increasing US access to Australian defense facilities, while the status quo was preferred by 65%.

The US and Australia are reaching out to bring more partners to work together in Australia’s north. This was given full expression in the ninth biennial Talisman Sabre exercises in Queensland (the largest bilateral US-Australia exercise). Launching the 2021 exercise, Australia’s Defense Minister Peter Dutton said it would strengthen interoperability, bolster cooperative defence activities with countries in the region, and enhance collective combat readiness for complex operations. More than 17,000 military personnel from seven nations took part, across all domains—maritime, land, air, information and cyber, and space: 8,300 Australians; 8,000 Americans; 200 Japanese; 250 Canadians; 230 South Koreans; 130 British and 20 from New Zealand.

In June 2021, Dutton was asked whether he anticipated more marines in Darwin and US naval vessels operating out of the Perth naval base. His reply: ‘Yes I do.’ The minister said the US role had not been hidden from the Australian public since the 2011 Force Posture agreement on the marines. Dutton said A$8 billion will be spent on infrastructure works across the north of Australia in the next decade “on facilities to train jointly with the US and others.”

The Northern Territory has 1.3 million sq. km, so each of its 250,000 people has the equivalent of five sq. km—that’s a lot of space for a couple of thousand Marines, but the US presence is certainly noticed in the north. Reflecting on the territory’s experience of living with the marines, a retired Australian Army major-general wrote that the initiative had been “painfully slow to gather momentum,” particularly negotiating the cost-sharing arrangements.

The US Army War College Fellow at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Todd C Hanks, wrote that the US finds itself relying more on its allies than at any time in the past 50 years, particularly in the Indo-Pacific. The lieutenant colonel observed that while Australia valued its independence and self-reliance, its defense strategy and policies were increasingly aligned with the US effort to deal with the rapid rise of China as a near-peer competitor. He pointed to areas for growth of US–Australia cooperation:

- expand the Australian defense industrial base while securing and hardening supply chains; a joint venture to manufacture critical ammunition within Australia;

- increase the US Army force posture in northern Australia to take advantage of the region’s strategic geography;

- increase multinational training opportunities, especially for the Quad; and

- expand Australia’s defense partnership with Indonesia.

Afghanistan

For Australia, as for the US, Afghanistan was the longest war—40,000 Australian Defence personnel and civilians served in Afghanistan and 41 soldiers were killed. The total cost of Australian military operations in Afghanistan in the 20 years to June 2021 was A$8.5 billion. In a statement to Parliament on the Taliban victory, Prime Minister Morrison said many of those who served in Afghanistan were asking a simple question: Was it worth it? The prime minister answered: “Yes, it was. … As with any war, of course, there are errors and miscalculations, and history won’t shy away from that, and neither will we, as a free people.” Before Kabul airport closed, Australia’s part of the airlift had evacuated some 4,100 people—this included more than 3200 Australians and Afghan nationals with Australian visas, while the remainder were people airlifted on behalf of Australia’s coalition partners.

Foreign Minister Payne spoke in the Senate on the disappointment and pain many felt: “I fear for Afghan women and girls, their rights to education, work and freedom of movement. I fear for the many women I have met over the years of my visits to their country.” Australia would support international efforts to pressure the Taliban to meet its responsibilities, Payne said.

Labor’s shadow foreign minister, Penny Wong, told the Senate that Australia would have to grapple with what it had learnt about the limits of military intervention and foreign-backed statehood: “This mission did not end the way we wanted or hoped, and we should face that reality squarely. These are issues which demand responsible and sober engagement, and all who served and all who will be called on in the future to serve are entitled to that honest appraisal.” One element of that appraisal is war crimes in Afghanistan: 25 Australian soldiers stand accused of murdering 39 unarmed Afghan civilians or prisoners and cruelly treating two others, between 2005 and 2016. After a four-year inquiry, Paul Brereton, a New South Wales Supreme Court judge and a major-general in the Army Reserve, handed a report to the Inspector General of the Australian Defence Force. Brereton found credible information about 23 incidents in which one or more noncombatants or prisoners were unlawfully killed by or at the direction of Australian soldiers in circumstances which, if accepted by a jury, would be the war crime of murder. Some of these incidents involved a single victim, and some multiple victims. None of these incidents occurred under pressure in the heat of battle, the report said.

The chief of the Australian Defence Force, Gen. Angus Campbell, said the report detailed credible information regarding deeply disturbing allegations of unlawful killings: “To the people of Afghanistan, on behalf of the Australian Defence Force I sincerely and unreservedly apologise for any wrongdoing by Australian soldiers.” One of Australia’s most experienced defense reporters, the executive editor of The Strategist, Brendan Nicholson, wrote that the war in Afghanistan profoundly changed the Australian Army and had a significant impact on the whole defense force. The special forces had become isolated from the rest of the army, and a small minority of them got out of control:

“When concerns were raised about possible unlawful killings, the army ordered its own investigations. What they uncovered was profoundly disturbing. Something had gone badly wrong on the Afghanistan missions—a deep-seated and distorted warrior ethos permeated parts of the SAS and an entrenched culture of impunity had taken hold there.”

Amid the question about Afghanistan, one judgment about those two decades is set: the bipartisan support for the war from the major parties at every stage of the saga. The consensus between the Liberal and Labor parties was remarkable for showing few cracks and never publicly wavering. Both sides of politics owned the war in government and neither deviated when in opposition. As anything that looked like victory faded to invisibility, this bipartisan unity persisted; the consensus held even as the nature of the war changed and evolved, Australian casualties rose, and popular Australian support fell away. The bipartisan backing for Afghanistan rested on the US alliance, but it drew strength from the professional nature of the Australia Defence Force.

Liberal and Labor leaders were sending volunteers, not conscripts. The three-way dynamic was the relationship between an Australian population skeptical of the war, a professional military, and Australia’s politicians committed to Afghanistan as an alliance duty. Australians supported their military even if they opposed the war. That allowed a series of governments to uphold the mission. The cost was carried by the ADF—as demonstrated by the war crimes findings and now a royal commission into suicides by Australian military veterans. Paul Kelly, editor-at-large of The Australian, described it as an “ignominious rout” (Aug. 21-22). Kelly saw a strategic wake-up call for Australia that would mean a rethinking of “the US alliance in terms of our rhetoric, our responsibilities and our self-reliance.” Kelly surveyed four former Australian prime ministers about the impact on the alliance.

Tony Abbott (prime minister 2013–15) predicted a more adventurous China and Russia as US allies adjusted and questioned. Labor’s Kevin Rudd (prime minister 2007–10 and 2013) told Kelly that the alliance was an essential strategic guarantee, but Australia must recognize the isolationist dimension in the US worldview.

The future course offered by Rudd in his 2021 book The Case for Courage:

- higher military spending;

- deeper military partnership with the US;

- growing the nation’s population for a “Big Australia”; and

- an even greater role in the Indo-Pacific and Pacific Islands.

Malcolm Turnbull (2015 to 2018) told Kelly the issue was not just US reliability but US competence: “I respect the decision President Biden took in the circumstances. … Yet the outcome is appalling and many people are left abandoned. This has damaged America’s standing and prestige.”

John Howard (prime minister 1996 to 2007) said the US was weary of the prolonged involvement, but the withdrawal was clumsy, with a determination to meet the deadline of the 9/11 anniversary: “My initial reaction is that this bungle has taken place in the context of Afghanistan and the different views of Democrats and Republicans over how to fight Islamist terrorism. I still have a lot of confidence in the American relationship. I believe if it was put to the test the Americans would honor the ANZUS treaty.”

The positive take is that the US is heading out of Afghanistan into the Indo-Pacific. The tough take is that this is Biden’s first major blunder as president. Australia confronts its own Afghanistan scars and an Australian army changed by two decades of war.

Conclusion: ANZUS at 70

At the end of the reporting period, on Sept. 1, Australia’s House of Representatives marked the 70th anniversary of the signing of the ANZUS treaty between Australia, New Zealand, and the United States. Morrison’s speech used alliance language echoing that of the previous 14 prime ministers who’ve held office since the treaty was signed. He told the House that “ANZUS is the foundation stone of Australia’s national security and a key pillar for peace and stability in our Indo-Pacific region.” The alliance was based on trust and mutual respect, which meant the treaty “breathes and adapts with each passing generation,” Morrison said: “Our two peoples see the world through the same lens. The treaty we celebrate today has leaned into the world, dealing with it honestly as it is but in the hope of it becoming more as we would like it to be. At the launch of the Defence strategic update last year, I said we live in a region where peace, stability, and prosperity cannot be taken for granted.”

Opposition Leader Anthony Albanese said President Biden’s early embrace of the Quad was a welcome commitment to the region: “We welcome the return of American leadership and the rules-based order under President Biden, and his dedicated effort in repairing alliances. But even when the United States stepped back from its longstanding leadership on trade and other forms of multilateralism during the Trump administration, Australia held the line and, importantly, held the door open for our friends in the United States.” The bipartisan support for ANZUS in the parliamentary motion is reflected in polling by the United States Studies Centre, based at Sydney University.

The center finds a significant positive shift in Australian attitudes toward the alliance. Polling from 2007 indicated just one-fifth (19%) of respondents thought the alliance with the US helped “reduce the risk of an attack on Australia.” When asked the same question in 2021, this doubled with 38% agreeing the alliance reduces the risk of an attack on Australia. And 85% of Australians think it is “very” or “somewhat” likely that the US would “substantially assist” Australia if it faced a military threat. The head of the center, Simon Jackman, said Australians see the alliance as a “vital and dependable foundation” of Australia’s security, yet views about the relationship were “tinged by wariness about Australia’s independence and realism about the nature and limits of US power.”

Some bits of the alliance vocabulary are hefting more weight, such as the focus on values. It is striking to hear Australia’s realist defenseniks continually circling back to the role and worth of democracy in the contest with China. Always a reliable gloss on ANZUS speeches, democracy gets more space and attention today as an important piece of alliance software. Australia has spent 70 years obsessing about the meaning and strength of ANZUS as the structure and links built on the treaty have evolved and grown. The idea of alliance that came out of World War II was born as ANZUS in the Korean war and survived defeat in Vietnam. This alliance resilience means it will survive Afghanistan. The 70thanniversary marks the history of a relationship that is strong enough to adapt, and has delivered much for Australia and the US.

Oct. 6: 2020: The foreign ministers of the Quad meet in Tokyo.

Oct. 14, 2020: Reports that Chinese state-owned energy providers and steel mills are told to stop importing Australian coal. The Australian mining company, BHP, says Chinese customers have cancelled coal orders.

Nov. 6, 2020: A report on Australian military war crimes in Afghanistan is handed to the Chief of the Defence Force.

Nov. 12, 2020: Prime Minister Scott Morrison announces a new investigative body to examine findings of war crimes by Australian soldiers in Afghanistan.

Nov. 17, 2020: Morrison visits Japan to meet new Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide, reaching in-principle agreement on a Japan-Australia defense pact, allowing closer military cooperation on exercises and shared use of resources, including bases and fuel.

Dec. 13, 2020: Free trade agreement between the South Pacific, Australia, and New Zealand begins operation.

Dec. 15, 2020: Morrison says a Chinese ban on Australia coal breaches WTO rules.

Dec. 23, 2020: Foreign Minister Marise Payne announces a “Sydney Dialogue” designed to be the “the world’s premier summit on emerging, critical and cyber technologies.”

Jan. 5, 2021: Payne notes refusal of a UK court to extradite Australian citizen Julian Assange to the US, stating that “Australia is not a party to the case and will continue to respect the ongoing legal process.”

Jan. 10, 2021: Australia joins Canada, the UK, and US in expressing serious concern at the mass arrests of 55 politicians and activists in Hong Kong for subversion under the National Security Law.

Jan. 21, 2021: Morrison holds the first annual leaders’ talks with Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc under the Australia-Vietnam strategic partnership.

Jan. 27, 2021: Morrison has a virtual meeting with Malaysian Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin to elevate the Australia–Malaysia relationship to a “comprehensive strategic partnership.”

Jan. 27, 2021: Defence Minister Linda Reynolds has her first discussion with new US Defense Secretary, Lloyd Austin.

Feb. 3, 2021: First phone conversation between Morrison and President Biden takes place.

Feb. 5, 2021: Australian journalist and former business anchor for Chinese state media outlet China Global Television Network (CGTN) Cheng Lei is formally arrested by PRC authorities after six months in detention.

March 12–13, 2021: First Quad leaders’ meeting of Australia, India, Japan, and the US takes place.

April 10, 2021: Australia announces vaccines for the South Pacific.

April 15, 2021: Morrison announces withdrawal of Australia’s last remaining troops in Afghanistan, in line with US action.

April 21, 2021: Using foreign relations powers, Canberra cancels four deals between the state of Victoria and foreign nations, including a Belt and Road Initiative agreement with China.

May 6, 2021: China suspends its Strategic Economic Dialogue with Australia.

May 10, 2021: Payne visits Kabul to affirm support for the Afghanistan government

May 13, 2021: Payne has talks in Washington with Blinken.

June 9, 2021: Australian Federal Police reported to have taken part in a global “sting” operation against organized crime suspects across 12 countries who use an encrypted app designed by police.

June 9, 2021: Ninth Japan-Australia 2+2 Foreign and Defense Ministerial Consultations take place.

July 8, 2021: Kathryn Campbell is appointed secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, following Frances Adamson who leaves to become governor of South Australia.

July 11, 2021: Payne issues statement marking the fifth anniversary of South China Sea Arbitral Award that dismissed China’s claim to “historical rights or maritime rights” in the South China Sea.

July 14 2021: Defense Minister Peter Dutton addresses opening ceremony of Exercise Talisman Sabre.

Aug. 13, 2021: Payne issues a statement on Australian journalist Cheng Lei’s detention in China for one year, expressing serious concern about her welfare, and “a lack of transparency about the reasons for Ms. Cheng’s detention.”

Aug. 16, 2021: Australia’s prime minister, defense minister, and foreign minister call on the Taliban’s leadership to be “responsible and accountable for the conduct of its forces” and for no threat or hindrance to those wanting to leave Afghanistan.

Aug. 18, 2021: Australia allocates initial 3,000 humanitarian places for Afghan nationals to come to Australia; since 2013, 8,500 Afghans have resettled in Australia.

Aug. 30, 2021: Payne makes joint statement with 94 other nations on assurances from the Taliban on travel out of Afghanistan.

Sept. 1, 2021: Labor Party says that if elected it would conduct Australia’s first Defence Posture Review since 2012.

Sept. 1, 2021: Morrison presents motion to the House of Representatives marking the 70th anniversary of the signing of the ANZUS treaty.