Articles

Australia has changed government and the political war over climate change draws to a close after raging for 15 years. The new Labor government led by Anthony Albanese promises continuity on foreign and defense policy, delivered with a different tone. In the government’s first 100 days, it chipped some ice from the frosty relationship with China. Ending a Beijing ban on meetings with Australian ministers that was in its third year, Chinese ministers had face-to-face talks with Australia’s foreign minister and defense minister. Albanese’s observation that dealing with China will continue to be difficult was demonstrated by a diplomatic duel in the South Pacific, as Canberra pushed back at Beijing’s ambition for a greater security role in islands. Two major defense announcements are due in the first months of 2023: the plan for an Australian nuclear submarine, based on the AUKUS agreement with the US and UK, plus a re-set of Australia’s military and strategic posture because of the toughest security environment in decades. Labor says the alliance with the US should go “beyond interoperability to interchangeability” so the two militaries can “operate seamlessly together at speed.”

The New Labor Government

The Labor Party’s victory in the May 21 election ended nine years of government by the Liberal-National Coalition. The voters delivered a realignment of politics as well as power. Labor achieved a narrow win that will remake much. Anthony Albanese is Australia’s 31st prime minister. He is only the fourth Labor leader to take the party from opposition to government since World War II. Labor crept back into office with a historically low primary vote in the House of Representatives, where governments are made. In the 151-seat House, Labor won a bare majority of 77 seats; 16 seats are on the crossbench, held by independents and the Greens; the Liberal-National Coalition won 58 seats. The coalition would need a net gain of 18 seats in the House to win majority government. The Greens and independents thus form a firewall for Labor’s hold on power at the next federal due election in 2025.

The Liberal Party is pushed into political purgatory, losing lower house seats to Labor, the Greens, and independents. Electorally, the heart was ripped from the Liberals as they lost a swathe of heartland suburban seats that have defined the party. The erosion of the party base is symbolized by the loss of the Melbourne seat of Kooyong by the Liberal deputy leader, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg. Kooyong isn’t just heartland, it’s the heart—the seat once held by Robert Menzies, founder of the Liberal Party. The Liberal identity crisis arrives as a heart attack. In the heartland seats of Sydney and Melbourne, the Liberals lost to independents rather than Labor.

The new force in the House of Representatives is the “teal” independents—the teal color imagery merges the Liberal’s traditional blue livery with the climate imperatives of the Greens. The teals attacked from the Liberal center in those heartland seats, as the base rose up, with women independents defeated sitting Liberal (male) members of Parliament. In claiming victory on election night, Albanese declared, “Together we can end the climate wars.” Victory for the teals, as much as for Labor, defined the result of the climate war for the Liberal Party.

Figure 1 Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese celebrates his victory during the Labor Party election night event on May 21, 2022 in Sydney, Australia. Photo: James D. Morgan/Getty Images

The Liberal history of climate change denialism crashed into an electorate that had decided the science is settled. Climate change was nominated as the top election issue by 25% of respondents in a survey by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. As prime minister from August 2018 to May 2022, Scott Morrison strained to shift the Coalition closer to the science side of the fight, but he becomes another casualty of the climate war. Morrison joins the four prime ministers who preceded him–Malcolm Turnbull (Liberal), Tony Abbott (Liberal), Julia Gillard (Labor), and Kevin Rudd (Labor)–as leaders whose careers were deeply wounded or truncated by the climate conflict. A world turning away from carbon challenges Australia, which is the third biggest exporter (behind Russia and Saudi Arabia) of fossil fuels.

Morrison confronted COVID-19, climate change and China, and the new era of strategic competition. On climate, Morrison dragged the Coalition to the point where he was talking about “decarbonization” as a positive rather than a negative. Morrison moved some distance from his performance as treasurer in 2017, when he brandished a lump of coalin Parliament. Being the champions of coal helped the Coalition in previous elections, but harmed it in 2022.

Morrison’s achievement as prime minister was to disarm the Liberal denialism on net-zero emissions—although he had less success with the junior member of the Coalition government, the National Party. The first bill Labor introduced when Parliament resumed in July was legislation reducing Australia’s net greenhouse gas emissions to 43% below 2005 levels by 2030.

Speaking to Parliament on the Climate Change Bill, Albanese said “the decade of inaction and denial is over.” Australia was “out of the naughty corner in international forums,” Albanese said. “We are once again engaging with the global community who understand the importance of acting on climate change and understand that this is also not just an environmental issue, this is the biggest economic transformation that we will see globally in our lifetime, as big and as significant as the Industrial Revolution.”

Albanese Gets on the Plane

In his first weeks as prime minster, Albanese flew to Japan for the Quad summit; to Jakarta to meet Indonesia’s president; to a NATO summit in Madrid; to Kyiv to express support for Ukraine; and to Paris to repair relations over the junking of Australia’s submarine contract with France. Elected on a Saturday May 21, Albanese was sworn-in as prime minister on Monday and immediately got on a plane to fly to Tokyo for the May 24 Quad summit with US President Joe Biden, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio. The welcome jest from Biden was, “You were sworn in, you got on a plane, and if you fall asleep while you’re here, it’s okay.”

Figure 2 Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese meets with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy in Kyiv. Photo: Official Website, President of the Ukraine

“The government in Australia has changed,” Albanese said in Tokyo, but “the Government’s commitment to the Quad has not changed.” Albanese told the summit: “I acknowledge all that the Quad has achieved, standing together for a free, open, and resilient Indo-Pacific region and working together to tackle the biggest challenges of our time, including climate change and the security of our region. My government is committed to working with your countries, and we are committed to the Quad. The new Australian government’s priorities align with the Quad agenda.”

Labor’s attitude to the Quad today (version 2.0) differs markedly from its rejection of the first version of the Quad. Back in 2008, the Rudd Labor government walked away from Quad 1.0 because ties with Japan or India could endanger its relationship with China, as Kevin Rudd argued: “Australia would run the risk of being left high and dry as a result of future foreign policy departures in Tokyo or Delhi.” Labor has gone from negative to positive about the Quad, reflecting the shift from positive to negative in Australia’s view of China. When Quad 2.0 was created in 2017, Labor matched the Coalition government’s enthusiasm for the reborn grouping.

By June 6, Albanese was in Indonesia for an annual summit with President Joko Widodo on the “comprehensive strategic partnership.” The trip continues the tradition, built over 50 years, that the first bilateral visit by a new Australian prime minister is to Jakarta. “Australia’s relationship with Indonesia is one of our most important,” Albanese said. “We’re linked not just by geography, but we are linked by choice.” The focus on Indonesia feeds into a core Australian policy, repeated by Albanese, that “ASEAN and ASEAN‑led institutions are at the absolute centre of our vision for the Indo-Pacific.”

At the NATO summit at the end of June, Albanese was one of four leaders from the Asia-Pacific: Australia, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea. He said the Russian invasion of Ukraine had “solidified the support amongst democratic countries for the rules-based international order,” while Australia well understood the view of NATO’s new statement on China’s “systemic challenges.”

Dealing with China, Dueling in the South Pacific

In the last major foreign policy speech of his prime ministership on March 7, Scott Morrison attacked China and Russia as “a new arc of autocracy” seeking “to challenge and reset the world order in their own image.” Australia, he said, “faced its most difficult and dangerous security environment in 80 years.” China’s growing power and influence were a geostrategic fact, Morrison said, and “China has become more assertive, and is using its power in ways that are causing concern to nations across the region and beyond.”

In the national budget delivered on March 29 as the prelude to the election, the Morrison government warned Australia had to be “realistic about the growing threats we face” in a “world less stable,” confronting “aggression” and “coercion.” The state-of-the-world survey from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) in the budget gave a flavor of the incoming government brief the department would give Labor. A “deteriorating strategic environment” confronted Australia, DFAT reported, as great power competition intensified: “The rules, norms and institutions that support Australia’s prosperity and security are under persistent pressure.”

The word “pressure” is a one-word description of what China has been applying to Australia from trade to the South Pacific. The Australia-China diplomatic icy age is five years old. China has been doing the trade squeeze on Australia for two years. China placed tariffs and restrictions on Australian exports worth about A$20 billion, also advising Chinese students not to study at Australian universities. During the campaign for the May election, a shared Labor-Liberal line was to blame Beijing for the chill. The three-word summation used by both sides was the phrase, “China has changed.”

As he headed to Tokyo for the Quad summit, two days after the election, Albanese commented: “The relationship with China will remain a difficult one. I said that before the election. That has not changed. It is China that has changed, not Australia.” An early response from China to the new government was to end a ban on meetings with Australian ministers that was in its third year. Labor’s defense minister and foreign minister each had face-to-face discussions with Chinese counterparts. Three weeks into government, on his first trip as deputy prime minister and defense minister, Richard Marles at the Shangri-La dialogue in Singapore had a one-hour meeting with China’s Defense Minister Wei Fenghe. Marles called it “an important first step” that took place without any conditions: “[W]hile there is a change of tone, there is absolutely no change in the substance of Australia’s national interests.”

Figure 3 Fiji Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama shakes hands with Australian Foreign Minister Penny Wong during her visit to Fiji, May 26, 2022. Photo: Facebook/Penny Wong

In Bali at a G20 foreign ministers meeting in July, Foreign Minister Penny Wong met China’s State Councilor and Minister of Foreign Affairs, Wang Yi. Wong said they discussed differences and the need “for the relationship to be stabilized.” Wong’s meeting with Wang was a face-to-face version of the diplomatic duel the two foreign ministers had been waging in their travels around the South Pacific. No previous Australian foreign minister has spent so much time in the islands in their first months in the job as Penny Wong, visiting Fiji twice, Samoa and Tonga, New Zealand and Solomon Islands, Papua New and Timor-Leste.

On her fourth day as foreign minister, Wong’s first major speech was to the secretariat of the Pacific Islands Forum in Suva: “Our region has not faced a more vexing set of circumstances for decades. The triple challenges of climate, COVID and strategic contest will challenge us in new ways. We understand that the security of any one Pacific family member rests on security for all.” The line about the security of each island state and strategic contest was a jab at China’s Wang Yi, who did an eight-country, 10-day tour of the islands selling China’s proposal for a South Pacific pact on security and development. China’s impact on Australia’s election campaign came from an unexpected direction, when China announced in April that it had signed a security pact with Solomon Islands. A leaked draft of the treaty said China would supply Solomon Islands police, armed police, and support from the People’s Liberation Army.

The draft allowed China to “make ship visits to, carry out logistical replenishment in, and have stopover and transition in Solomon Islands, and the relevant forces of China can be used to protect the safety of Chinese personnel and major projects in the Solomon Islands.” Morrison said a Chinese military base in the Solomons would be a “red line” for Australia and the US. Labor said the pact was a policy failure by the Morrison government, with the sharpest line from Penny Wong: “This is the worst foreign policy blunder in the Pacific that Australia has seen since the end of World War II.” Wong’s call was shaky history but a deadly political thrust at a Coalition government that wanted to campaign on its security credentials and its record standing up to China.

A wry rubric of Canberra is that South Pacific governments can’t be bought but they can be rented. Today’s version is that China wants to do more than rent an island government; it wants “elite capture.” The nightmare of elite capture in a Pacific capital is China getting control of “dual use” infrastructure—a civilian port with military uses. Canberra twitches every time Beijing casts its eye across ports in PNG, Vanuatu, or Solomon Islands. A China surprise, a new base in the islands, was nominated by the US Indo-Pacific coordinator Kurt Campbell as “the issue that I’m most concerned about over the next year or two.” He was speaking in January at the launch of an Australia chair at the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Campbell said the US had to lift its game in the South Pacific, to match what’s done by Australia and New Zealand: “But that’s an area that we need much stronger commitment. And I’m, frankly, looking to Australia as the lead here. And we, as the United States, have to be a better deputy sheriff to them in this overall effort.”

AUKUS, the US Alliance and a Defense Review

Labor promises two sets of defense announcements in the first quarter of 2023:

- the plan for a nuclear submarine under the AUKUS agreement with the US and UK;

- a reset of Australia’s military posture based on a defense strategic review.

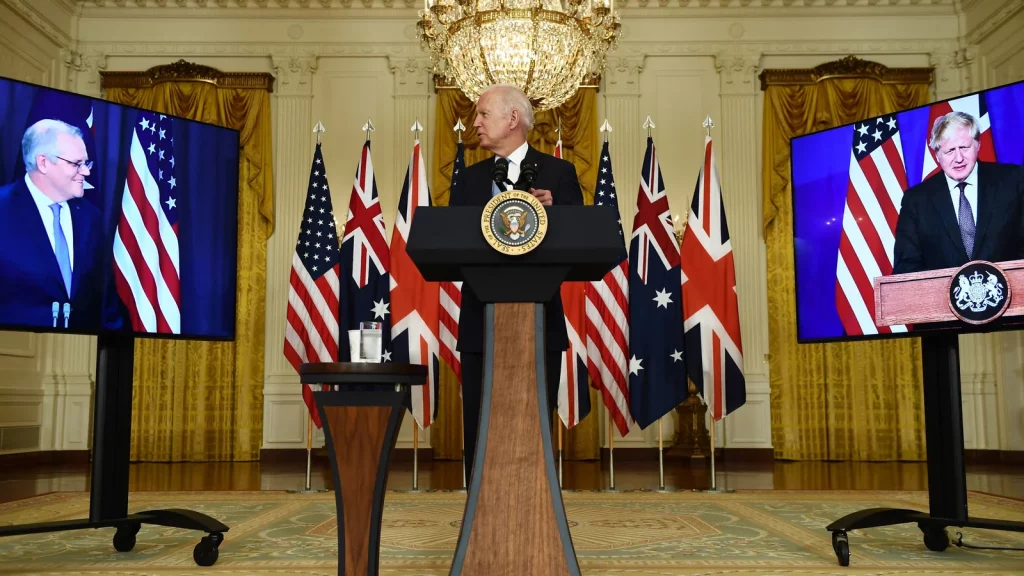

AUKUS was announced on Sept. 16, 2021, hailed by Scott Morrison as the most important step in the alliance with the US since the ANZUS treaty was signed in 1951. If the nuclear submarines surface, then AUKUS will be Morrison’s strategic monument in the same way Robert Menzies claimed ANZUS as one of his greatest achievements. Australia will use AUKUS to get “nuclear-powered submarine technology, leveraging decades of experience from the US and UK.” Under an 18-month timeline, to March 2023, the three nations will decide on “the optimal pathway to deliver at least eight nuclear-powered submarines for Australia.” Canberra stated it had no plans to acquire nuclear weapons and the nuclear submarines would “remain consistent with Australia’s longstanding commitment to nuclear non-proliferation.” AUKUS will also be used to build joint capabilities and interoperability in cyber, capabilities, artificial intelligence, and quantum technologies.

Figure 4 US President Joe Biden is virtually joined by Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison, and British Prime Minister Boris Johnson for the announcement of AUKUS on Sept. 16, 2021. Photo: Brendan Smialowski/AFP via Getty Images

Neither the US nor the UK has spare capacity in their nuclear submarine construction programs. And Australia’s Navy must start from scratch to create nuclear expertise and train crews. Defense Minister Marles describes AUKUS as a “huge” task: “The decision about which submarine we go with and how quickly we can get that, the cost, and how we make sure we’re doing this in a way that does not give rise to proliferation, all of that work is happening at a pace. We look forward to being able to make the final announcements on time in the first part of next year.”

The creation of AUKUS sank Australia’s A$90 billion contract with France to create the Attack-class conventional submarine. French President Emmanuel Macron lashed out at Morrison claiming Australia lied to France. Biden told Macron the US had been “clumsy” in the reaching the secret agreement with Australia. The secrecy the Morrison government applied to France also extended to the Labor Party.

The Biden administration insisted it would go ahead with AUKUS only if Labor gave it solid backing. But Morrison waited four-and-a-half months before informing Labor. During the election campaign, Albanese condemned Morrison for seeking political advantage by telling Labor about AUKUS only the day before it was announced. “The Biden administration sought reassurance from the Australian government that Australian Labor had been consulted on these issues,” Albanese said. “It is extraordinary that the prime minister broke that faith and trust with our most important ally by not briefing Australian Labor on these issues.” Morrison replied that he’d maintained full secrecy and did not want to give Labor the chance to leak details of the negotiations: “AUKUS is a ground-breaking agreement, the most significant defense security agreement Australia has entered into in over 70 years. And I was not going to risk that on the Labor Party.”

Rather than baulking, Labor embraced AUKUS and the switch from conventional submarines to nuclear-powered subs. Labor’s decision had political and strategic dimensions, maintaining the bipartisan consensus on the US alliance as it entered a new era, and putting fresh life into the “oldest relationship” with the UK. The Albanese government has linked the AUKUS decision timeline to a review of Australia’s defense force and force posture. The chosen path to the nuclear submarine and the defense changes are both due to be announced in March.

Marles said the AUKUS choices and the Defence Strategic Review will run concurrently and cross-pollinate: “Together, these bodies of work are going to lay the foundations for defense policy for our country for decades to come.” The strategic review is being run by former Labor Defense Minister Stephen Smith and a former chief of the Australian Defence Force, Sir Angus Houston.

In his first trip to Washington as defense minister, Marles said Australia wanted to see “how we best integrate and operate with the US.” The “integration” ambition defined by Marles is to reach towards “interchangeability”: “We are making big investments in defense capital infrastructure to support, maintain, and sustain the growing number of Australian and American forces. We will operationalize a regular [US] presence and an increased exercise tempo. We will move beyond interoperability to interchangeability. And we will ensure we have all the enablers in place to operate seamlessly together at speed.”

Getting closer to the US to “increase the range and lethality” of the Australian Defence Force helps answer the new strategic dilemmas that Marles describes: “For the first time in decades, we are thinking hard about the security of our own strategic geography; the viability of our trade and supply routes.” In setting up the defense review, Labor embraces a key conclusion of the Morrison government’s 2020 Defence Strategic Update: Australia no longer has 10 years’ warning time of a conventional attack. The 10-year window was previously based on the time it would take an adversary to prepare and mobilize to cross the sea-air gap and tackle the distances that define the continent. Discarding the 10-year warning time meant ditching the comfort of 50 years of Australian strategic theology.

Camelot to Canberra, Australia’s Man in Washington

The new US ambassador to Canberra, Caroline Kennedy, arrived in Australia on July 22. The Kennedy name meant the “Camelot to Canberra” line got plenty of headline use. The diplomatic significance of the appointment, though, is as a statement not just about the US-Australia relationship, but the trilateral with Japan. Kennedy becomes the second US ambassador this century to serve in both Canberra and Tokyo, where she was ambassador from 2013 to 2017. Her trilateral service follows that of Tom Schieffer, a friend and business partner of President George W. Bush, who was ambassador to Australia (2001-2005) and Japan (2005-2009).

In her confirmation hearing before the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Kennedy said Australia could be a model for the US in responding to China. “Certainly Australia most recently has been challenged by Chinese economic coercion and I think the United States can learn a lot from their response,” Kennedy said. “They’ve stood firm and I think they’ve managed to come together with a bipartisan foreign policy and a greater and deeper partnership with us in the security and diplomatic areas, as well as across the board.”

Figure 5 Caroline Kennedy is sworn in as the US ambassador to Australia. Photo: Twitter/@USEmbAustralia

In her arrival statement in Australia, Kennedy said, “This is a critical time in the history of our two countries. What we do together in the next few years will determine the future of the region and of the planet, and I can’t wait to get started.” As Kennedy was preparing to head to Canberra, Australia’s previous ambassador to the US, Joe Hockey, was releasing his memoir Diplomatic, on serving in Washington from January 2016 to January 2020. A member of Parliament for 19 years, finishing as Treasurer in Tony Abbott’s government, Hockey starts with the big truth that shapes the life of any Australian ambassador in the US—history has “made America fundamentally different from us.”

“Many demons,” Hockey writes, lurk “in the American psyche.” And that’s about as far as he goes on the “inherent differences.” The Hockey emphasis is on the “long and friendly history” between the two allies: “It’s a bit like a successful marriage: we like each other a lot, we are not identical and do not always agree; however, we have shared our lives over many years. We are loyal to each other and we really enjoy each other’s company.” Hockey went to Washington because his dream to become prime minister was dead. His luck deserted him in the series of political car crashes that marked the Liberal Party death struggle between Tony Abbott and Malcolm Turnbull. The chapter headed “Goodbye, Canberra” has a subhead reference to “politics at its worst,” and the smile dims as he lets fly: ‘Within our [Abbott] government, there were too many who were more focused on polls than policy. The sickness of populism afflicts the weak. That didn’t stop them from engaging in duplicity and deceit.”

From Washington, Hockey did most of his work with Canberra on a secure phone, talking to the prime minister, ministers, and department heads. Others in Australia’s embassy wrote the “cables” that are a central expression of the existence of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (acting as circulatory system and thinking process). Hockey’s Canberra understandings (“the sharpest knives always come from your own side”) explain that phone preference—“given my past life as a politician, if I wrote any cables, I couldn’t rely on all the people reading them not to share them with the media.”

A well-directed leak can sink you. As Hockey notes, Britain’s ambassador to the US had to resign in 2019 after a London leak of his cables claiming that President Donald Trump “radiates insecurity” and describing the White House as “clumsy and inept.” Hitting Washington at the start of 2016 for the final year of Barack Obama’s administration, Hockey witnessed the close but not familiar relationship between Obama and Prime Minister Turnbull: “Both men had a healthy love of detailed intellectual discourse—especially their own. Like two history professors discussing dialectical materialism, their conversation was eye-watering but hardly warm.”

Then comes the chapter headed simply “Trumpageddon.” On the Hockey telling, he read the signs of the presidential campaign and started building bridges to Trump, while Canberra was in denial till the votes came in. Hockey says Trump “was one of the most authentic political candidates I had ever seen,” even though he was “confronting, rude and naïve.” When he later spent time with the president, even on the golf course, Trump was constantly questioning, churning through ideas and trying out lines: “Most political leaders are narcissists. They not only need to be the centre of attention, they often think they are the smartest people in the room. They also have fantastic egos. They believe they can charm the leg off a billiard table with their quick wit and nice smile. Enter Donald Trump.”

Hockey describes a White House that lacked leadership and leaked like a sieve, with everyone competing for Trump’s attention and approval. The leaking meant the Washington Post quickly got the transcript of the president’s notorious phone conversation with Prime Minister Turnbull on Jan. 28, 2017, a week after the inauguration. Turnbull needed Trump to commit to the deal struck with Obama for the US to accept refugees Australia had exiled to Nauru and Papua New Guinea. Trump berated Turnbull over a “dumb deal” and the “worst deal ever.”

When Hockey answered the phone and spoke with Turnbull “straight after the conversation, he was shaken. His voice was quivering and he was clearly upset.” Hockey says the Trump-Turnbull call was “disastrous.” The ambassador put on his politician’s helmet and marched into the White House to argue the dangers of a “massive deterioration in the alliance.”

The public crisis—“the madness that followed the leaked phone call”—offered a chance to lock in the deal. The strong foundations of the alliance, Hockey says, “can’t be undermined by the whims of a leader.” Thinking like a politician, Hockey launched a campaign with a strong story: “100 years of Mateship,” marking the two countries’ shared military history—Australia is the only country in the world to fight side by side with the United States in every major conflict’ since the Battle of Hamel on the Western Front in 1918. Mateship is a complicated concept for Australia, and the campaign got plenty of criticism in Australia for being blokey or subservient. For the US, though, mateship struck a chord and Hockey says it became a “successful touchstone.” Certainly, mateship seemed to work with Trump. “After the disastrous first phone call,” Hockey writes, “Australia went on to have a series of political and economic wins during the Trump presidency.”

Hockey exalts that the “mates” theme was embraced by President Joe Biden in his address marking the 70th anniversary of the ANZUS alliance: “Through the years, Australians and Americans have built an unsurpassed partnership and an easy mateship grounded on shared values and shared vision.”

The Hockey prediction is that Biden will not run for a second term as president. And he links that with a prediction that Trump, too, is unlikely to run: “Apart from his age [Trump will be 78 in 2024], and the likelihood the Democrats will seek to legally bar him from running, I don’t think he could bear the prospect of losing again.” With questions in the air about both Trump and Biden, Hockey judges, “America hasn’t been in such a precarious position for a long time.” As he finishes the book, Hockey writes of how luck and quick reactions spared the ambassador an obituary about a culture-clash smash in New York.

When an Australian jumps out of a taxi and prepares to make a dash across 5th Avenue, the habit of a lifetime is to look the wrong way for the traffic. Australia drives on the left; America drives on the right. It’s a simple metaphor for the many different ways of looking and moving of the two nations. Rushing for a late-night drink in the city that never sleeps, Australia’s ambassador to the US, Joe Hockey, stopped his taxi by Central Park and dashed across the avenue, checking in the Australian direction. That “near-fatal error,” Hockey observes, was “like so many who think they understand America.”

Sept. 9, 2021: Indonesia-Australia Foreign and Defence Ministers 2+2 meeting takes place in Jakarta.

Sept. 11, 2021: Inaugural India-Australia 2+2 Ministerial Dialogue between Foreign and Defence Ministers takes place in New Delhi.

Sept. 13, 2021: Australia-South Korea Foreign and Defence Ministers 2+2 Meeting takes place in Seoul.

Sept. 13, 2021: Opposition Leader Anthony Albanese says a Labor government will make climate change “central to the US alliance.”

Sept. 16, 2021: 31st Australia-United States Ministerial Consultations AUSMIN takes place in Washington.

Sept. 16, 2021: China applies to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans Pacific Partnership. As one of 11 members of CPTPP, Australia has a veto over China’s proposed membership.

Sept. 17, 2021: France recalls ambassadors from Washington and Canberra in protest at Australia’s submarine switch, calling US and Australian behavior “unacceptable between allies and partners.”

Sept. 20, 2021: Responding to concerns about Australia’s approach to the region because of the new AUKUS partnership, Australia’s ambassador to ASEAN makes a statement on “Australia’s steadfast commitment to ASEAN centrality,” supporting the “objectives and principles of the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific.”

Sept. 21, 2021: US Defence Logistics Agency awards contract to build the largest fuel storage facility in Darwin, to hold 300 million liters of fuel.

Sept. 22, 2021: President Biden and PM Morrison meet in New York.

Sept. 22, 2021: Taiwan applies to join the CPTPP.

Sept. 24, 2021: PM Morrison gives a virtual address to the UN General Assembly.

Sept. 24, 2021: Agreement reached on “an enduring regional processing capability in Nauru,” supporting the policy that would-be asylum seekers trying to reach Australia by boat are transferred to Nauru for assessment of claims.

Sept. 24, 2021: First in-person Quad summit of Australia, India, Japan, and the US, hosted by President Biden, takes place.

Oct. 6, 2021: Regional processing in Papua New Guinea of “people who have attempted to travel to Australia illegally by boat” ends, with the PNG contract to cease on Dec. 31, 2021.

Oct. 6, 2021: Golden Jubilee (50th anniversary) of the Five Power Defence Arrangements between Malaysia, Singapore, Australia, Britain, and New Zealand, marked by Exercise BERSAMA GOLD 21, conducted across Singapore, Malaysia and parts of the South China Sea.

Oct. 8, 2021: Defence Minister Peter Dutton chairs annual South Pacific Defence Ministers’ Meeting.

Oct. 15, 2021: Australia supports international statement expressing deep concern at “the dire situation in Myanmar, and its worsening implications for regional stability,” and supporting the Special Envoy of the ASEAN Chair on Myanmar.

Oct. 16, 2021: FM Marise Payne convenes and co-chairs fourth virtual Pacific Women Leaders’ Network meeting.

Oct. 20, 2021: United States Marine Rotational Force-Darwin (MRF-D) departs from the Northern Territory at the end of its rotation.

Oct. 21, 2021: Australia implements legislation for the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (RCEP).

Oct. 25, 2021: Australian federal government provides $1.33 billion so Australia’s Telstra can buy Digicel Pacific, the top telecommunications operator in Papua New Guinea, Nauru, Samoa, Vanuatu, Tonga, and Fiji. The move blocks a possible sale of Digicel to China.

Oct. 27, 2021: PM Morrison and FM Payne virtually attend inaugural ASEAN-Australian Leaders’ Summit, whichagrees to establish a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership between ASEAN and Australia. Morrison told the summit that “AUKUS does not change Australia’s commitment to ASEAN or the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific.”

Nov. 1, 2021: With COVID restrictions lifted, Australians are allowed to travel overseas without quarantining for 14 days on return.

Nov. 1, 2021: At climate summit in Glasgow, PM Morrison pledges Australia will reach net zero emissions by 2050 by “driving down the cost of technology and enabling it to be adopted at scale.”

Nov. 5, 2021: FM Payne leaves to visit Malaysia, Cambodia, Vietnam and Indonesia to discuss recovery from COVID-19 and the new Comprehensive Strategic Partnership between ASEAN and Australia.

Nov. 10, 2021: ASEAN-Australia Informal Defence Ministers’ Meeting takes place.

Nov. 17, 2021: At the first “Sydney Dialogue,” PM Morrison announces Australia’s Blueprint for Critical Technologies, listing 63 critical technologies.

Nov. 17, 2021: Canberra updates guidelines to strengthen Australian universities against foreign interference.

Dec. 8, 2021: Australia says it will not send official representatives to the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics.

Dec. 13, 2021: President of South Korea Moon Jae-in visits Canberra to mark the 60th anniversary of diplomatic relations. Moon and PM Morrison announce creation of a comprehensive strategic partnership. Canberra locks in a billion-dollar weapons contract with South Korea, the largest-ever military deal with an Asian nation.

Dec. 15, 2021: President Biden nominates Caroline Kennedy to be US ambassador to Australia

Jan. 6, 2022: Australia becomes Japan’s first formal defense partner after the US, as PM Morrison and PM Kishida Fumio hold a virtual summit to sign a defense treaty for interoperability and collaboration.

Jan. 21, 2022: Australia-UK Ministerial Consultations (AUKMIN) 2022, in Sydney, involving defense and foreign ministers, pledge deepening strategic cooperation in the Indo-Pacific.

Jan. 27, 2022: Australia’s Air Force announces it will deploy aircraft and personnel to Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands for joint exercises with the US and Japan.

Feb. 1, 2022: Australia joins the US, European Union, and others in a joint statement marking the one-year anniversary of Myanmar’s military coup, expressing “grave concern” and pointing to the coup’s “devastating impact.”

Feb. 6, 2022: FM Payne notes the one-year anniversary of the detention of Australian Professor Sean Turnell by “the Myanmar military,” repeating the call for his immediate release.

Feb 11, 2022: 4th Quad foreign ministers meeting held in Melbourne.

Feb. 17, 2022: Patrol aircraft on a surveillance flight over Australia’s northern approaches is illuminated by laser by a Chinese Navy vessel. Australia protests to China, calling the lasing “a serious safety incident.”

Feb. 21, 2022: Australia reopens borders to all visa holders who are double-vaccinated against COVID-19, allowing in tourists, business travelers, and other visitors.

Feb. 24, 2022: PM Morrison and FM Payne condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, announcing financial and business sanctions.

March 1, 2022: PM Morrison announces he has COVID-19 and will isolate for seven days while still performing all responsibilities as prime minister.

March 4, 2022: A virtual summit of the Quad leaders (Australia, India, Japan, and the US) takes place to discuss Ukraine.

March 7, 2022: PM Morrison announces Australia will build a new submarine base on its east coast to support future nuclear-powered submarines.

March 10, 2022: PM Morrison announces plans to increases the size of the Australian Defence Force by 30% by 2040, taking the total permanent ADF to almost 80,000 personnel. Defence’s total permanent workforce is to increase to over 101,000 by 2040 – an increase of 18,500 over the target set in the 2020 Force Structure Plan.

March 14, 2022: Australia joins the Netherlands to start legal action against Russia in the International Civil Aviation Organization for downing Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17 in 2014.

March 24, 2022: After refusing for nearly nine years, Australia announces it will accept New Zealand’s offer to resettle refugees detained at offshore detention centres on Nauru and Manus Island in Papua New Guinea.

March 25, 2022: Top cyber security adviser to President Joe Biden, Anne Neuberger, says the US would invoke the alliance to support Australia if it suffers a major cyberattack.

March 29, 2022: Australia’s federal budget presented to parliament.

March 31, 2022: Australian journalist Cheng Lei faces a closed trial in Beijing, 19 months after she was detained and accused of providing state secrets to foreigners. Australia’s ambassador to China is barred from attending the trial.

April 2, 2022: India and Australia sign an economic and trade agreement to eliminate tariffs on more than 85% of Australian goods exports to India and 96% of Indian imports into Australia. PM Morrison said the India deal “built on our strong security partnership and our joint efforts in the Quad, which has created the opportunity for our economic relationship to advance to a new level.”

April 5, 2022: FM Payne travels to Brussels for a NATO Foreign Affairs Ministers’ meeting to discuss a “coordinated international response to Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine.”

April 6, 2022: AUKUS announces trilateral cooperation on hypersonics and counter-hypersonics, and electronic warfare capabilities, to deepen cooperation on defense innovation.

April 6, 2022: Australia sends two intelligence chiefs to press Solomon Islands not to sign a proposed security pact with China. Visiting Honiara, head of the Australian Secret Intelligence Service, Paul Symon, and director-general of the Office of National Intelligence, Andrew Shearer, brief Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare on Australia’s security fears.

April 10, 2022: PM Morrison announces that Australia’s federal election will be held May 21.

April 12, 2022: Australia’s Minister for Minister for International Development and the Pacific Zed Seselja flies to Honiara to press the Solomon Islands government not to sign a security cooperation treaty with China.

April 19, 2022: China announces it has signed a security pact with Solomon Islands. Australia says it is “deeply disappointed” at the agreement which could “undermine stability in our region.”

May 21, 2022: Labor Party wins Australia’s national election, ending nine years of rule by the Liberal-National coalition government. Labor leader Anthony Albanese will be the new prime minister. Outgoing prime minister Scott Morrison steps down as leader of the Liberal Party.

May 23, 2022: Labor leader Albanese is sworn in as Australia’s 31st prime minister. With new Foreign Minister Penny Wong, Albanese departs Canberra for Tokyo for a meeting of the Quad.

May 24, 2022: Quad summit in Tokyo involving the leaders of Australia, Japan, India and the United States takes place.

May 26, 2022: A Chinese jet flies dangerously close to an RAAF P-8 surveillance aircraft over the South China Sea, releasing aluminium chaff ingested in the P-8’s engine.

May 26, 2022: FM Wong visits Fiji for talks with Fiji’s Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama, seeking to counter China’s proposal for a pact with South Pacific nations on policing, security and data communication.

May 30, 2022: At a conference in Fiji with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, 10 South Pacific nations walk away from a trade and security deal, refusing to sign a multilateral agreement with China.

June 6, 2022: PM Albanese meets Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo in Jakarta.

June 10, 2022: New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern has talks in Sydney with PM Albanese. Ardern said the new Labor government offered the chance for a “reset” with New Zealand. Albanese said the two countries were in “lockstep” in the South Pacific.

June 16, 2022: Australia updates its commitment to the United Nations convention on climate change, pledging to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 43% below 2005 levels by 2030, putting Australia on track to achieve net zero emissions by 2050.

June 23, 2022: Deputy Prime Minister Richard Marles attends Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting in Rwanda.

June 25, 2022: Australia, Japan, New Zealand, United Kingdom, and the US launch the Partners in the Blue Pacific Initiative.

June 28, 2022: PM Albanese arrives in Madrid for the NATO summit.

July 2, 2022: PM Albanese meets President Emmanuel Macron in Paris, promising a “new start’ to relations, following the breach over the Morrison government’s termination of the French submarine contract in 2021.

July 3, 2022: PM Albanese visits Kyiv to meet Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, expressing Australia’s supportfor the people of Ukraine and the defense of their homeland.’

July 13, 2022: PM Albanese travels to Fiji for the Pacific Island Forum summit.

July 22, 2022: New US Ambassador Caroline Kennedy arrives in Australia.

July 25, 2022: US and Australia co-host 2022 Indo-Pacific Chiefs of Defense conference in Sydney.

Aug. 3, 2022: Australia announces a Defence Strategic Review to examine military force structure, force posture and preparedness, and investment priorities.

Aug. 5, 2022: FM Wong addresses the ASEAN-Australia Ministerial Meeting in Phnom Penh, introducing herself as “the first Australian Foreign Minister who is from Southeast Asia.”

Aug. 5, 2022: FM Wong meets US Secretary of State Antony Blinken, and Japan’s Foreign Minister Hayashi Yoshimasa, in Phnom Penh, expressing their commitment to the trilateral partnership.

Aug. 26, 2022: PM Albanese establishes an inquiry into the secret actions of previous PM Morrison in appointing himself to administer departments other than the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

Aug 31, 2022: Papua New Guinea says it wants a new security treaty with Australia, and with New Zealand and the United States.

Sept. 1, 2022: A jobs and skills summit takes place at parliament house in Canberra.

Sept. 2, 2022: Australia lifts the target for permanent migrant entry visas from 160,000 to 195,000 people for the 2022-23 financial year.

Sept. 6, 2022: President of Timor-Leste Jose Ramos-Horta visits Australia.