Articles

The first months of 2022 were also the last of Moon Jae-in’s presidency. Inter-Korean relations have been frozen for the past three years, and 2022 saw no change there. In April Moon exchanged letters with Kim Jong Un, whose warm tenor belied the reality on the ground. The North was already testing more and better missiles faster than ever, and tearing down ROK-built facilities at the shuttered Mount Kumgang resort. Days after his billets-doux with Moon, speaking at a military parade, Kim threatened ominously to widen the contexts in which his ever-improving nuclear arsenal might be used. All these challenges confront a new leader in Seoul. Unlike Moon, the conservative Yoon Suk-yeol is new to politics, but not minded to indulge Kim. His ministerial and other appointees, who have now taken over, are already striking a firmer note—while also stressing their pragmatism and openness to dialogue. Very recently a fresh threat—or perhaps an opportunity—has arisen, with the North finally admitting an outbreak of COVID-19. Yoon promptly offered vaccine aid. It remains to be seen if Kim will accept this, how he will handle the omicron outbreak, whether he will proceed with a widely expected nuclear test, and how Yoon and Biden will handle an ever more complex crisis.

A Watershed Moment

This article, indeed this issue, is being published on the cusp of change in South Korean politics. When I began to write, the liberal Moon Jae-in was eking out his final days in the Blue House: the secluded compound in northern Seoul that was hitherto the president’s office and residence (analogous to the more centrally located White House in Washington, DC). By the time you read this, the conservative Yoon Suk-yeol—a former chief prosecutor with no prior political experience until last year, who won the March 9 election by the slimmest of margins for the conservative opposition People Power Party (PPP) —will be serving his first week as president of the Republic of Korea (ROK). Only not in the Blue House, which he spurned as remote from the people—Moon had originally said the same, until the logistics of moving defeated him—but in new premises in the Ministry of National Defense (MND) compound in Seoul’s Yongsan district. Carving out this new presidential office—a work still in progress—required part of MND to be evicted. Meanwhile, the Blue House (Cheongwadae) has now become a park, open to the public.

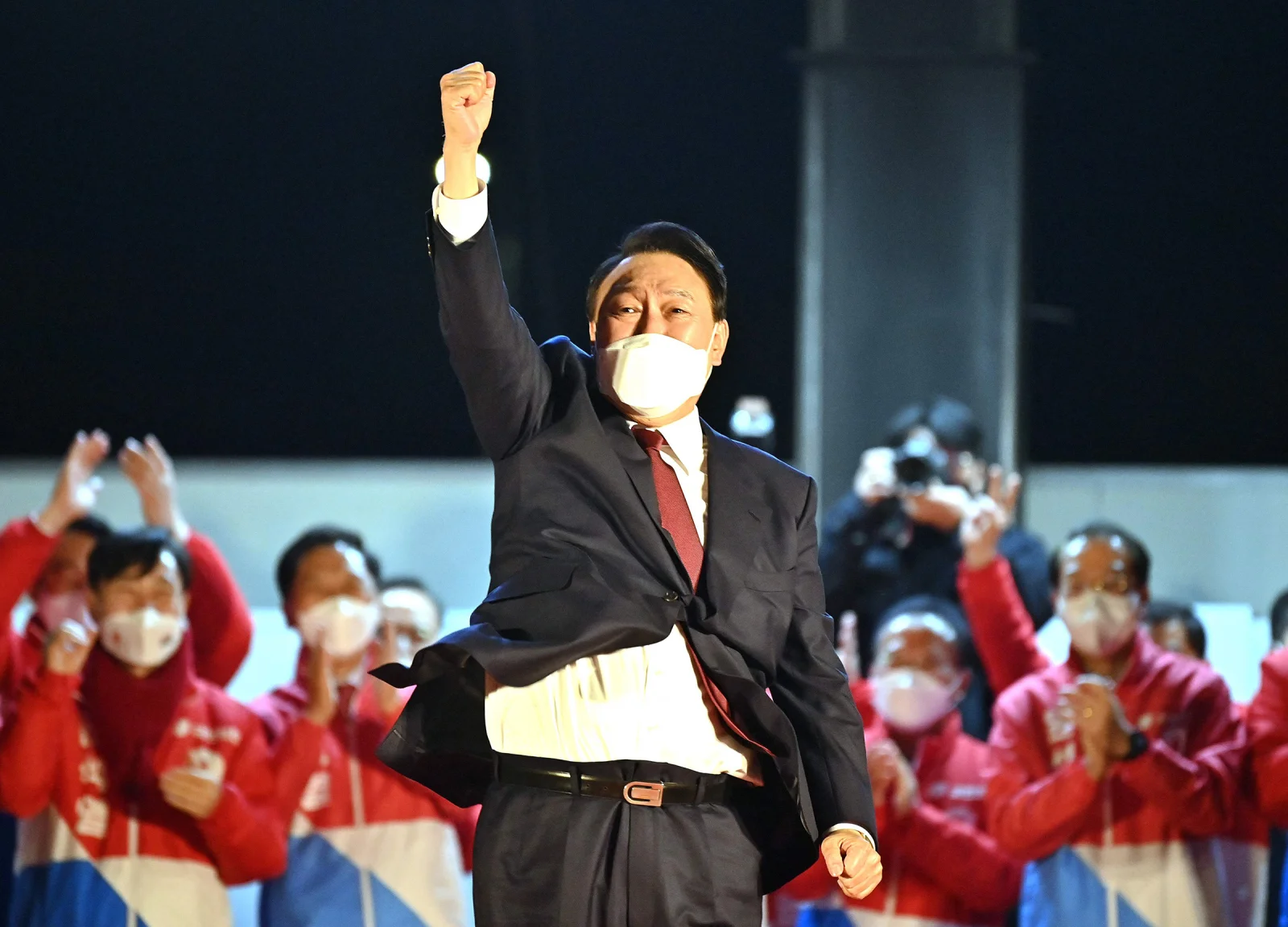

Figure 1 South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol gestures to supporters on March 10, 2022 outside of party headquarters in Seoul. Photo: Time via Getty Images

But I digress, already.

All being well, Yoon will serve five years until May 2027, when someone will succeed him—unless the Constitution is amended to permit a second term. (This has been regularly discussed, but has yet to gain enough traction to become a serious proposal.)

At this key turning point for South Korea and the peninsula, besides covering events during the first four months of 2022, it seems too right to look forward and back. This article will try to sum up the Moon era in inter-Korean relations overall (we began this in the previous issue), while also considering what Yoon may do and how he will be different. Not only is this task timely, but we have the space, since once again there was almost no direct contact between the two Koreas during this period—as has been the case for three years. Which is not to say the peninsula was uneventful (is it ever?), especially on the missile front.

Many More Missiles

Writing these articles can feel like trying to pen a rough first draft of history. Being so close to the events—in medias res, literally in the midst of things—an author may wonder if the immediate take will stand the test of time; or whether matters that loom large now will turn out to be ephemeral, forgotten in the longer run.

Sometimes, though, one can be confident. 2022 is not yet half over, but we already know that—as so often—Pyongyang is making the running: setting familiar, yet heightened, challenges to its interlocutors and foes. As most readers will know, Kim Jong Un began the year with a bang: January was the DPRK’s most intensive month ever for missile launches. After a brief lull during the Beijing Winter Olympics, this barrage resumed in late February and has continued ever since. As of May 12, there had been 16 separate launch events in 2022 so far, featuring a variety of weapons, including in March the first test of an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) since late 2017—after Pyongyang warned on Jan. 20 that it was reconsidering “restarting all temporarily-suspended activities.” Satellite images appear to confirm what that warning implies: a nuclear test may be imminent too, perhaps as early as this month (May). That again would be the first time since 2017. Still another likely prospect is a fresh satellite launch, using dual-use technology that also advances WMD rocketry.

These disconcerting developments are widely covered elsewhere, and transcend this chapter’s bilateral remit. They are, however, the most important thing to happen on the peninsula so far in 2022, together with regime change in Seoul. As such, they must be borne in mind as the essential backdrop and context to everything discussed here. Similarly, though far from Korea, the most ominous new factor bearing on the future of North-South relations is Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February. The potential impact of this is considered below.

Yoon Backs Preemption—Or Does He?

Kim Jong Un’s missile flurry had multiple motives. One was to test not just his own weapons, but the enemy’s reactions. President Moon’s National Security Council (NSC) responded with characteristic mildness, usually expressing “strong regret” or “grave regret.” By contrast, Yoon Suk-yeol—at that stage a candidate, in a close race—caused a stir by appearing to endorse a preemptive strike on the North’s missiles in some circumstances. Soon after, he said it again (for full details and links, see the chronology). In other remarks he offered olive branches.

A political neophyte, Yoon sometimes seemed to be learning on the job in a gaffe-prone campaign. He will have to learn fast. On March 9 voters narrowly elected him president, defeating the continuity candidate, Lee Jae-myung of Moon’s ruling Democratic Party (DP). Had Lee won, he would have continued Moon’s engagement approach to North Korea. What Yoon will actually do remains to be seen, but his preemption talk has been toned down since.

Yoon moved swiftly to set up a transition committee, and then to nominate ministers. His transition team, announced on March 18, included no portfolio specifically on inter-Korean relations. Past presidents-elect, including conservatives, had appointed advisers to what was called a foreign, security, and unification sub-committee, but Yoon ditched the U-word. His three picks in the foreign/defense space—long-time adviser Kim Sung-han, plus Kim Tae-hyo, and ex-general Lee Jong-sup—are all seen as hawkish on North Korea. There was speculation that Yoon, already controversially committed to abolishing the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family (MGEF) as supposedly redundant, might emulate another rightwing president, Lee Myung-bak (2008-13), and seek to get rid of the Ministry of Unification (MOU). Lee failed in that bid, because he lacked a majority in the National Assembly. Yoon too faces a DP-controlled legislature at least until elections in April 2024, so existing ministries look safe for now.

Yet transition teams are short-lived and can only advise. Ministers last longer and have power—if not much on either front in South Korea, with its strong presidency and frequent Cabinet reshuffles. Yoon’s ministerial nominations in foreign affairs, defense, and indeed unification appeared to soften the tone, compared to his transition team (though there is one overlap). Foreign Minister Park Jin is a mild and urbane figure (this author knew him long ago as a young lecturer in England; he has an Oxford D Phil). Lee Jong-sup, in transition from the transition team to become Minister of National Defense (MND), assured lawmakers that he had no plan to scrap 2018’s inter-Korean military accord, as some conservatives demand.

Especially interesting is the “Yoonification” minister. Kwon Young-se, a long-time lawmaker, ex-ambassador to China, and sometime law-school classmate of Yoon, opposed the idea of scrapping MOU when it was resurrected last year by the PPP’s combative young chairman Lee Jun-seok. Both at and ahead of his confirmation hearings, despite disagreeing with specific Moon-era policies—he rightly opposes the fantasy of restoring tourism to Mount Kumgang, and has hinted at reconsidering the ban on sending leaflets into the North—Kwon was careful to suggest continuity rather than change. He explicitly rejected the ABM—Anything But Moon—approach to handling North Korea, saying this was not the “right way.”

Threats, Demolition—and Billets-Doux

The final weeks of Moon Jae-in’s presidency brought, not for the first time, contradictory developments. First, the good news: He and Kim exchanged letters, as they have done from time to time. (The means is unrevealed, but in 2018 they agreed to install a direct hotline. No more was heard of this, but conceivably it exists and could be used to send faxes, still a thing in the DPRK; but I speculate.) On April 20 Moon wrote to Kim to say goodbye. Pyongyang revealed this on April 22, and Seoul confirmed it the same day. Neither side published the actual texts, but by both accounts the tone was respectful, if tinged with melancholy that they had not achieved more. According to KCNA, Kim “appreciated the pains and effort taken by Moon Jae In for the great cause of the nation until the last days of his term of office…The exchange of the personal letters between the top leaders of the north and the south is an expression of their deep trust.”

Really? Actions speak louder than words. This year’s missile volleys aside, these pleasantries came just weeks after the North reportedly began carrying out its threat, first made in 2019 but postponed due to the pandemic, to demolish Southern-built and owned (though long since confiscated) facilities at the former Mount Kumgang resort, which has seen no ROK tourists since one was shot dead there in 2008. Seoul demanded an explanation, but has had no reply.

Also, some words speak louder than others. Simultaneously with the destruction at Mount Kumgang, after a six-month silence Kim Jong Un’s sister, Kim Yo Jong, issued two back to back statements (just as she had in Sept; those were appended to our last article) on April 2 and 4. Both tore into ROK Defense Minister Suh Wook—a “senseless and scum-like guy”—for talking about preemptive strikes. Her second rant was quite strange, as her remarks often are: threatening South Korea’s army with nuclear annihilation, while insisting there was “no ground” for the South to feel menaced. If her works are ever collected, as is the DPRK way, that slim volume will at least be a racier read than her father’s and grandfather’s turgid tomes: less formal, more haphazard, ditzier even, but ultimately no less weird and menacing.

Ukraine Casts a Long Shadow

Ukraine is far from Korea, and the Moon government has tried to keep its distance. The ROK was not among 31 countries which President Volodymyr Zelenskyy thanked by name for their support on April 27 (nor was Japan). The DPRK, meanwhile, wholeheartedly backs Russia.

Distant or not, the war in Ukraine has concentrated minds in Korea: publicly in Seoul, but no doubt also in Pyongyang. Seen from North Korea, Ukraine’s vulnerability to invasion can only confirm the Kim regime’s belief that possessing nuclear weapons is a crucial guarantee against such a fate. South Korea’s take is rather different. Russia’s aggression crosses and annuls many red lines, ominously rendering the unthinkable a necessary object of thought.

Figure 2 North Korean leader Kim Jong Un and Russian President Vladimir Putin meet in Vladivostok, April 25, 2019. Source: NKNews.org via Kremlin

Put simply: If Putin can do it, might Kim Jong Un? Not that KPA tanks would or could now roll across the heavily defended DMZ, as they crossed the 38th parallel in June 1950. But might a nuclear-armed DPRK now be emboldened to threaten a nonnuclear ROK, in ways that would be hard to counter without risking conflagration? Questions like this, hitherto seen as abstract (or confined to contrarians like BR Myers, too glibly dismissed by a centrist consensus as extreme), now look alarmingly real. Complacency is ill-advised, especially after Kim Jong Un’s gnomic remarks in April on when nuclear weapons might be used. The new Yoon government will be thinking hard about all this, amid a predictable clamor for the ROK to have its own nuclear arsenal, a view long espoused by a majority of South Koreans.

Yoon’s Inauguration Speech: Mild Towards Pyongyang

Yoon Suk-yeol was duly inaugurated on May 10. Though technically falling into the period covered by Comparative Connections’ next issue, since this journal’s publishing schedule permits (just!) it would be a perverse disservice to readers not to address right now the issue on everyone’s minds: How will inter-Korean relations fare after regime change in Seoul?

On his Nordpolitik, as noted above Yoon has given contradictory signals. His inauguration speech, excerpted as an Appendix below, was strikingly mild. North Korea’s WMD threat, which he has sometimes said may require a preemptive strike, did not even get a whole sentence, just a subordinate clause: “While North Korea’s nuclear weapon programs are a threat not only to our security and that of Northeast Asia…” But the main thrust was positive, for the sentence continues: “…the door to dialogue will remain open so that we can peacefully resolve this threat.” Money was dangled too, with talk of “an audacious plan that will vastly strengthen North Korea’s economy and improve the quality of life for its people.”

We have been here before, many a time. In one form or another, every ROK president since Chun Doo-hwan (even) has tried to bribe—sorry, incentivize—the DPRK to give up its nukes. Two of them, Kim Dae-jung (1998-2003) and Roh Moo-hyun (2003-08), implemented such a policy—aka “Sunshine,” fully cataloged and analyzed in this journal at the time. Actually, this was on a loss-leader basis: Seoul gave the money (both over and under the table), in the vague and unfulfilled hope that this would create an atmosphere for denuclearization in due course. More recently, a decade ago during his first bid for the presidency (when Park Geun-hye defeated him), Roh’s mentee Moon Jae-in was advocating an “inter-Korean economic union,” no less. None of these initiatives had lasting success; most never got off the ground.

Will Yoon fare any better? I wish him well, but there are at least two grounds for skepticism. One is both obvious and well-known. The other is more implicit, and of his own making.

First, Kim Jong Un, like his father and grandfather before him, shows no sign of wanting to surrender his WMD, at any price. Some may retort that maybe the price has never been right yet, adducing a counterfactual what-if regarding February 2019’s US-DPRK summit in Hanoi. Suppose Trump had not walked away? But that was then. Kim Jong Un’s latest menacing nuclear threats, discussed above, scarcely inspire optimism.

Second, it is important to read Yoon’s remarks in their context: as in the Appendix below, or better yet within his full inauguration speech. An avowed disciple of Milton Friedman, Yoon believes that freedom is the supreme value. (The word appears 30 times, in a speech of fewer than 1,600 words in total.)

Does he mean it? Apparently so. And, freedom for whom? Everyone, it seems. Later in his speech—the antepenultimate paragraph, in fact, building toward a peroration—Yoon is clear that freedom is something to spread abroad, and Seoul should be doing this more. He says that not in the context of North Korea as such, but globally. This is a known theme of his, notably in an earlier article in February for Foreign Affairs titled: “South Korea Needs to Step Up.” Returning to the theme now, he says: “We must take on an even greater role in expanding freedom and human rights not just for ourselves but also for others” (emphasis added). If he is serious, that has far-reaching implications. This could change ROK policy on at least three fronts: refusing thus far to send arms to Ukraine; not joining other democracies in statements admonishing China over the Uyghurs and similar issues; and doing business worldwide even with the nastiest regimes (Myanmar post-coup is a rare partial exception).

Will he also press North Korea on human rights? This is a very familiar crux. Serious would-be engagers, from Kim Dae-jung to Moon Jae-in (the latter originally a human rights lawyer in South Korea, ironically) have kept silent on the DPRK’s appalling abuses. While all policy planning has to prioritize, the putative sequencing which posits “aid now, rights later” has proved no less dubious than its security twin: “aid now, peace later.” ROK NGOs working on human rights in the North are frankly glad to see Moon gone—some were harassed by his administration—and have hopes of Yoon. Yet if Yoon plays the human rights card with North Korea, he had better forget any “audacious” plan to bribe Kim Jong Un into denuclearization.

Pyongyang Admits COVID-19: Inter-Korean Opportunity?

As this journal went to press, a long-expected shoe finally dropped. Despite over two years of draconian border controls, which have seriously hurt the economy, the coronavirus has, at last, reached North Korea. Or, skeptics may say, the regime has finally admitted it. Two days after the first reports of a lockdown in Pyongyang, on May 12 the Politburo convened and admitted that “a most serious emergency case of the state occurred: A break was made on our emergency epidemic prevention front.” Prevention work was upgraded to emergency mode, amid predictable scapegoating: “The Political Bureau censured the epidemic prevention sectors for their carelessness, relaxation, irresponsibility, and inefficiency.” Kim Jong Un was pictured in a mask for what seems to be the first time.

Figure 3 Kim Jong Un pictured wearing a mask in state media during a meeting to discuss a COVID-19 outbreak in Pyongyang. Photo: KCTV via NKNews.org

If anyone deserves censure, it is not hard-pressed working-level cadres, but the leaders who for two years have perversely refused any assistance, crucially including vaccine supplies. With no North Koreans yet vaccinated, and many vulnerable due to undernourishment, this may prove devastating. Yet it is also an opportunity. MOU swiftly said that the new ROK government, like its predecessor, wants to help. A press statement affirmed that “support for North Koreans and the inter-Korean cooperation on quarantine and health care can be promoted at any time on a humanitarian level.”

Hitherto the North has rebuffed all such offers from Seoul, the WHO, and everyone else. Might an emergency make Kim Jong Un reconsider, as his father momentously did in 1995, when famine forced the DPRK to bite the bullet and asked for outside aid? Internal debates about pros and cons back then are surely being replicated in Pyongyang now. An upcoming meeting of the WPK Central Committee of the ruling, slated for early June “to discuss and decide some important issues,” may offer clues. Watch this space, and pray that North Korea’s long-suffering people are not about to suffer even more.

Appendix A: Sections covering North Korea (directly or implicitly) in President Yoon Suk-yeol’s inauguration speech on May 10

My fellow citizens, here in Korea and those abroad,

Liberal democracy creates lasting peace and peace is what safeguards our freedom. Peace is guaranteed when the international community that respects freedom and human rights come together as one.

Peace is not simply avoiding war—real peace is about allowing freedom and prosperity to flourish. Real peace is a lasting peace. Real peace is a sustainable peace.

Peace on the Korean Peninsula and Northeast Asia is the same—our region cannot be exempt from threats that endanger the peace of other regions.

We, as global citizens, must make a stand against any attempt that aims to take our freedom away, abuse human rights or destroy peace.

While North Korea’s nuclear weapon programs are a threat not only to our security and that of Northeast Asia, the door to dialogue will remain open so that we can peacefully resolve this threat.

If North Korea genuinely embarks on a process to complete denuclearization, we are prepared to work with the international community to present an audacious plan that will vastly strengthen North Korea’s economy and improve the quality of life for its people.

North Korea’s denuclearization will greatly contribute to bringing lasting peace and prosperity on the Korean Peninsula and beyond.

….

Korea is the 10th-largest economy in the world. It is incumbent upon us to take on a greater role befitting our stature as a global leader. We must actively protect and promote universal values and international norms that are based on freedom and respect for human rights. We must take on an even greater role in expanding freedom and human rights not just for ourselves but also for others. The international community expects us to do so. We must answer that call. [emphasis added]

[ends]

Appendix B: Remarks about nuclear forces in Kim Jong Un’s speech at April 25’s military parade in Pyongyang

In particular, the nuclear forces, the symbol of our national strength and the core of our military power, should be strengthened in terms of both quality and scale, so that they can perform nuclear combat capabilities in any situations of warfare, according to purposes and missions of different operations and by various means.

The prevailing situation demands that more proactive measures be taken to provide a firm and sustained guarantee for the modern character and military technological supremacy of our Republic’s armed forces.

To cope with the rapidly changing political and military situations and all the possible crises of the future, we will advance faster and more dynamically along the road of building up the self-defensive and modern armed forces, which we have followed unwaveringly, and, especially, will continue to take measures for further developing the nuclear forces of our state at the fastest possible speed.

The fundamental mission of our nuclear forces is to deter a war, but our nukes can never be confined to the single mission of war deterrent even at a time when a situation we are not desirous of at all is created on this land.

If any forces try to violate the fundamental interests of our state, our nuclear forces will have to decisively accomplish its unexpected second mission.

The nuclear forces of our Republic should be fully prepared to fulfil their responsible mission and put their unique deterrent in motion at any time.

[text ends]

Jan. 2, 2022: First reports come in that a man has entered North Korea from the South—yes, that way round—by crossing the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ).

Jan. 3, 2022: In his final New Year’s speech as South Korea’s president, Moon Jae-in says he will pursue an “irreversible path to peace” on the peninsula until his term ends in May: “I will not stop efforts to institutionalize sustainable peace…If we [the two Koreas] resume dialogue and cooperation, the international community will respond…I hope efforts for dialogue will continue in the next administration too.”

Jan. 3, 2022: South Korea’s Ministry of National Defense (MND) says it has had no response from North Korea to a message it sent on Jan. 2 via the western military communication line, urging the North to protect the border-crosser. Another report clarifies that while Pyongyang did acknowledge receipt of the message, sent twice, it made no comment on the protection request. MND also confirms that this is the same person who arrived by a similar route across the DMZ in November 2020.

Jan. 4, 2022: Amid reports that last week’s presumed returnee defector was suffering financial problems in South Korea, the Ministry of Unification (MOU) insists that the man—who worked as a cleaner—had received due resettlement support from the ROK government.

Jan. 5, 2022: President Moon urges the ROK military to “have a special sense of alert and responsibility.” Calling the “failure of security operations …a grave problem that should not have happened,” he demands a special inspection of front-line units to ensure no repetition.

Jan. 5, 2022: ROK JCS reports that North Korea fired an apparent ballistic missile over the East Sea (Sea of Japan). South Korea’s presidential National Security Council convenes, is briefed, and expresses concern. This is Pyongyang’s first such launch in 2022; its last was an SLBM in October. (Further missile tests follow, making January the most intensive month ever for DPRK missile launches.)

Jan. 5, 2022: Reacting to Pyongyang’s missile launch, President Moon voices “concerns that tensions could rise and a stalemate of inter-Korean relations could further deepen.” Yet South Korea should not give up on dialogue, and “North Korea also should make efforts in a more earnest manner.”

Jan. 5, 2022: After investigating Jan. 1’s redefector border crossing, the ROK Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) report that the man crossed into North Korea despite being caught five times on military surveillance cameras. Gen. Won In-choul, JCS chairman, admits: “We failed to carry out given duties properly…I apologize for causing concerns to the people.”

Jan. 6, 2022: ROK government says that next month it will launch a new inter-agency team, including MOU and the police, to support vulnerable defectors from the North. Last year MOU’s biannual survey found that 1,582 defectors needed help additional to the basic support package that all ex-DPRK arrivals receive. Almost half (47%) spoke of having psychological problems. The new team is duly inaugurated on Feb. 7; see below.

Jan. 6, 2022: Korea Times profiles Tim Peters, a Seoul-based US activist whose NGO, Helping Hands Korea, has since 1996 helped over 1,000 North Koreans in China to safety in third countries. Despite the pandemic, in 2020 HHK enabled more such evacuations than ever before as hitherto hidden sub-groups, such as the elderly or disabled, came to light.

Jan. 10, 2022: MOU says it is monitoring potential changes in how North Korea handles COVID-19, such as easing current strict border controls, after Rodong Sinmun—the main DPRK daily, organ of the ruling Workers’ Party (WPK)—avers that “we need to move to a better advanced, people-oriented epidemic work from one that focused on control measures.”

Jan. 10, 2022: Refuting recently publicized research claiming that as many as 771 of the 33,800 North Korean defectors in the South have moved on to third countries as of 2019, MOU insists the true figure for the five years 2016-20 is only 20 (which seems implausibly low.) It confirms, however, that as many as 31 have redefected to the North.

Jan. 11, 2022: After North Korea’s second missile launch in under a week, Yoon Suk-yeol, presidential candidate for the conservative opposition People Power Party (PPP), causes a stir by endorsing a preemptive strike if the North fires a nuclear-armed missile toward Seoul. He accuses Moon of enabling the North to further advance its missile program, by accepting its peace overtures and calling for sanctions to be lifted. Moon’s NSC expresses “strong regret” at the DPRK’s Jan. 11 launch—and several which follow.

Jan. 14, 2022: Shortly after the US sanctions six North Koreans and others involved in the DPRK’s WMD programs, MOU vows to continue to try to provide humanitarian aid to the North “regardless of the political or military situation.” (In the real world, since 2019 Pyongyang has spurned all such efforts by Seoul.)

Jan. 17, 2022: After a further brace of DPRK missile tests, Yoon Suk-yeol doubles down on preemptive strike talk. Posting on Facebook, he writes: “I will secure a preemptive strike capability known as Kill-Chain and build the surveillance and reconnaissance capability needed to monitor all parts of North Korea…Only strong deterrence against the North can guarantee the Republic of Korea’s peace.”

Jan. 20, 2022: Korean Central News Agency (KCNA) reports that on Jan. 19 a Politburo meeting of the DPRK’s ruling WPK, after decrying US “hostility,” decided “to promptly examine the issue of restarting all temporarily-suspended activities.” This refers to the North’s moratorium since Nov. 2017 on nuclear and ICBM tests.

Jan. 20, 2022: Reacting to Pyongyang’s statement, South Korea’s NSC says it will “prepare for the possibility of further deterioration of the situation, while continuing efforts to stabilize the situation on the Korean Peninsula and resume dialogue with North Korea.”

Jan. 20, 2022: MOU reports a further sharp drop last year in defector arrivals. Just 63 North Koreans—40 men and 23 women—reached the South in 2021, down from 229 in 2020 and 1,047 in 2019. The ministry attributes this to tightened DPRK-China border controls due to the coronavirus.

Jan. 24, 2022: Yoon Suk-yeol promises, if elected, to normalize joint military exercises with the US. He adds: “North Korea has been upgrading its nuclear capabilities and is making blatant provocations…The [Moon] administration’s Korean Peninsula peace process has completely failed.”

Jan. 25, 2022: Seoul Central District Court sentences a businessman, named only as Kim, to four years in jail for violating the National Security Act (NSA). Formerly a member of a pro-North student group, Kim was indicted in 2018 for buying a DPRK-made facial recognition software program in 2007, which he sold in the ROK as his own company’s work. In return he sent Pyongyang $860,000, plus unspecified military secrets. Kim denied the charges, claiming he had Seoul’s permission for his contacts with the North.

Jan. 25, 2022: Briefing “dozens of foreign diplomats,” including from the US, China, Japan and Russia, Unification Minister Lee In-young emphasizes that, notwithstanding Pyongyang’s missile launches, “dialogue and cooperation are the only solution for peace on the Korean Peninsula,” and Moon will pursue peace “to the last.” Lee adds that time is on no one’s side.

Jan. 25, 2022: ROK prosecutors indict defector-activist Park Sang-hak, head of Fighters for a Free North Korea (FFNK), for two launches of balloons carrying leaflets into North Korea last April. The charge is attempted violation of the revised Development of Inter-Korean Relations Act, as it is unconfirmed whether the balloons reached the DPRK. He also faces a separate indictment on charges of receiving illicit donations during 2015-19. (See also Feb. 15.)

Jan. 27, 2022: Dismissing a suit brought by former operators of factories in the now defunct Kaesong Industrial Complex (KIC), the ROK Constitutional Court rules that then-President Park Geun-hye’s suspension (in effect closure) of the KIC in February 2016, as a riposte to North Korean nuclear and missile tests, was constitutional. This did not violate the claimants’ property rights, even though “fair compensation has not been paid.”

Feb. 1, 2022: MOU says it has delivered Lunar New Year gifts of “daily necessities and other items” to young (aged 24 or under) North Korean defectors who are without families.

Feb. 3, 2022: Yonhap reports that on Jan. 26 the UN Security Council (UNSC)’s committee on DPRK sanctions gave the Inter-Korean Economic Cooperation Research Center, a South Korean NGO, a year-long waiver to send 20 thermal imaging cameras to North Korea. These will be used to help stave off COVID-29. This is the first such exemption granted this year.

Feb. 3, 2022: After Pyongyang’s Jan. 20 warning that its ICBM test moratorium may end, and its launch on Jan. 31 of a Hwasong-12 intermediate range missile (IRBM), an unnamed military official tells Yonhap, South Korea’s quasi-official news agency, that “at this point there isn’t any notable change or activity” in the North suggesting an imminent ICBM test.

Feb. 7, 2022: ROK government launches a nine-member inter-agency team to help North Korean defectors “suffering from economic and psychological difficulties.” (See also Jan. 6.)

Feb. 8, 2022: A survey of 2,465 North Korean defectors (rather a small sample) by MOU’s Korea Hana Foundation finds that in 2021 their average monthly wage was 2.27 million won ($1,920). This was 457,000 won below the national average, but the gap is narrowing: it was 599,000 won in 2019 and 520,000 won in 2020.

Feb. 9, 2022: Ahead of a meeting in Honolulu with his US and Japanese counterparts, Noh Kyu-duk, ROK special representative for Korean Peninsula peace and security affairs, says he hopes this “will be another opportunity for us to work toward engagement (with Pyongyang).”

Feb. 10, 2022: In a “joint written interview” with Yonhap and seven other international news agencies, President Moon says he is ready for to meet Kim Jong Un again, in any format and without preconditions: “Whether…face-to-face or virtual (sic) does not matter. Whatever method North Korea wants will be acceptable.” But he admits that the imminent Presidential election may make a fresh summit “inappropriate.” Warning that if Pyongyang ends its ICBM testing moratorium the peninsula could return to a “touch-and-go-crisis” as in 2017, Moon mourns the failure of the 2019 Trump-Kim summit in Hanoi: a “small deal” would have been better than no deal. He says a Kim-Biden summit is “just a matter of time,” and reiterates his support for a “peace declaration” despite Pyongyang’s unresponsiveness.

Feb. 10, 2022: MOU says the ROK government will provide financial support totaling 57.4 billion won ($48 million) to companies hit by the suspension of North-South exchanges. A mixture of subsidies and loans, this applies to firms which invested in the Kaesong Industrial Complex (KIC) and the Mount Kumgang tourist zone. Their actual losses are much larger.

Feb. 15, 2022: FFNK’s Park Sang-hak seeks leave to file suit with the Constitutional Court to determine whether the anti-leafleting law under which he is charged is unconstitutional. Park claims it infringes the ROK’s identity, independence and national dignity. (See also Jan. 25.)

Feb. 17, 2022: MND announces new plans for its Air Defense Missile Command (ADMC). Given North Korea’s escalating missile threat, from April ADMC will get more mid-range surface-to-air missiles (M-SAMs) and BM early-warning radars, and be renamed in English (name to be decided). April will also see the Army Missile Command relaunched (so to say) and expanded as the Army Missile Strategic Command.

Feb. 17, 2022: Incheon District Court hands double defector Yoo Tae-joon an 18-month jail sentence for trying to return to North Korea. Having first defected to South Korea in 1998, in 2000 Yoo returned to the North. He then redefected to the South (date not given), but in 2019 attempted to go North again, approaching the DPRK embassy in Hanoi. Rebuffed as a spy, he entered China where he was arrested—and presumably extradited to the ROK.

Feb. 18, 2022: An online survey of 75,524 elementary, middle and high school students, jointly conducted in November-December by MOU and the Ministry of Education (MOE), finds that 25%—up from 19.4% in 2019 and 24.2% in 2020—consider that Korean unification is unnecessary. Reasons cited include the economic burden (29.8%), potential social problems after unification (25%) and political differences (17%).

Feb. 21, 2022: Seoul Metropolitan Government (SMG) says it will increase its support for defectors, including free health checkups, online tutoring and more. 3.4 billion won ($2.85 million) has been budgeted, more than double last year’s 1.5 billion won. The avowed aim is to help defectors “gain complete independence and social integration, not only resettlement.”

Feb. 22, 2022: South Korea’s official Truth and Reconciliation Commission says that the (North) Korean People’s Army (KPA) killed “1,026 Christians and 119 Catholics” in a bid to “eliminate reactionary forces” during its retreat from the South after the allied Incheon landing in Sept. 1950 during the Korean War. (“Christians” here means Protestants; this usage is common in the ROK, which is the most Protestant country in Asia.)

Feb. 22, 2022: Song Young-gil, head of South Korea’s ruling Democratic Party (DP) tells visiting UN special rapporteur on DPRK human rights, Tomas Ojea Quintana, that the KIC could reopen if there were conditional sanctions relief and wages were paid in kind. Quintana reportedly says he supports reopening. There is in fact no such prospect, and Pyongyang may have other plans. (Song is running as DP candidate for mayor of Seoul in elections on June 1.)

Feb. 23, 2022: “Informed sources” tell Yonhapthat the Agency for Defense Development (ADD) today oversaw a successful test at Taean, 100 miles southwest of Seoul, of a long-range surface-to-air missile (L-SAM), being developed to counter DPRK missile threats.

Feb. 28, 2022: President Moon tells the Korea Army Academy that (in Yonhap’s summary): “Based on strong defense capabilities, South Korea has pushed for peace efforts on the Korean Peninsula and turned North Korea’s nuclear crisis into a mode of dialogue.” He adds that the ROK has the “biggest security burden” in the world: “For now, the top priority is to deter war between the South and North, but from a broader and long-term point of view, the geopolitical situation of the Korean Peninsula itself represents a grave security environment.”

March 8, 2022: DPRK patrol boat breaches the Northern Limit Line (NLL, the de facto maritime border in the Yellow/West Sea), seemingly chasing a stray Northern vessel which has also crossed the line. It retreats aftyer an Southern warship fires three warning shots. The ROK Navy apprehends the other DPRK vessel (story continues on March 9).

March 9, 2022: Yoon Suk-yeol narrowly wins South Korea’s presidential election for the PPP, defeating the DP’s Lee Jae-myung by just 0.73% (they poll 16,394,815 and 16,147,738 votes, respectively). Despite the tight margin, Lee swiftly concedes.

March 9, 2022: MND says it has sent back a DPRK vessel and its crew of seven, seized yesterday after breaching the NLL. The intruders explained that they accidentally crossed the line due to fog while transporting materials between two islands, and refused to eat until they were repatriated. Alert for provocations around election time, Seoul accepts that this was just a “navigational error and mechanical glitch.”

March 11, 2022: In an item headlined “20th ‘presidential’ election held in south Korea,” the DPRK’s Voice of Korea says (this is the full report): “Yun Sok Yol, candidate of the ‘People’s Strength’ (sic), a conservative opposition party, was elected ‘President’ by a small majority at the 20th ‘presidential’ election held in south Korea on March 9.” (Scare quotes and capitalization in original). VOK is for external consumption, so North Koreans are not privy to this news.

March 14, 2022: Amid signs that North Korea has begun dismantling South Korean-built and owned facilities at long-shuttered Mount Kumgang resort, as Kim Jong Un first threatened to do in 2019, MOU says it has received no new word from Pyongyang. Its spokesperson adds: “There shouldn’t be unilateral measures by the North that infringe upon our companies’ property rights, and all…issues should be resolved through consultations between the South and the North.”

March 15, 2022: Belatedly reporting a poll last August by the Korea National Defense University (KNDU), PPP Rep. Kang Dae-sik says that 70.6% of South Koreans believe North Korea will never denuclearize completely. 61.3% regard the DPRK as hostile, while 22.1% consider it a partner for cooperation. Over 80% reckon China would take the North’s side in any crisis on the peninsula. A slightly earlier survey, by the state-run Korean Institute for National Unification (KINU), found 90.7% skeptical about Pyongyang’s will to denuclearize.

March 22, 2022: Two days after the KPA fires four rounds from multiple rocket launchers (MRLs) into the West Sea, Yoon Suk-yeol calls this “a clear violation” of Sept. 2018’s inter-Korean military agreement. However ROK MND Suh Wook denies any breach, saying this took place “far north” of the border area covered by the accord. Yoon’s team shoot back that it violated the spirit of the agreement; they accuse Suh of “protecting” the North.

March 23, 2022: President-elect Yoon’s transition committee TC spokesperson says: “There will be no abolition of the unification ministry.” Rather, MOU will be restored to its “proper function” instead of just taking orders from the Blue House. The TC also denies that Yoon’s Nordpolitik will be hard-line.

March 23, 2022: “Informed source” tells Yonhap that MOU has formed a 10-member panel to review secret documents on the first two decades of inter-Korean talks (1971-91), with a view to publishing them. (See also April 15, below.)

March 24, 2022: Ending (as presaged on Jan. 20) its four-year moratorium on ICBM tests, North Korea stages what it celebrates as a successful first launch of the Hwasongpho-17: its largest missile, paraded but not yet known to have flown. Korean Central Television (KCTV) issues a highly untypical movie-style video of the launch.

March 24, 2022: In tougher terms than usual, Moon “strongly condemns” the North’s ICBM test as “a serious threat to the Korean Peninsula and beyond,” and “a scrapping on its own (sic) of a moratorium on ICBM tests that…Kim Jong Un promised to the international community.” This is also “a clear violation of UN Security Council resolutions.” Moon calls on Pyongyang to immediately stop actions that raise tensions and return to the dialogue table.

March 24, 2022: South Korea responds to North’s ICBM launch with a live-fire missile exercise in the East Sea (Sea of Japan). The JCS warns that “(we) have the ability and posture to precisely strike the origin of the missile launch and command and support facilities at any time.”

March 27, 2022: “Informed sources” claim that both the ROK and US military reckon the DPRK’s recent ICBM launch was not in fact a Hwasong-17, as officially touted, but rather the slightly smaller Hwasong-15, previously tested in 2017. They speculate that March 16’s failed test really was a Hwasong-17, and Pyongyang could not risk a second failure. On close inspection, KCTV’s video spliced footage from two launches, with different locations, time of day and weather. (That said, two earlier tests on Feb. 27 and March 5, announced as being satellite-related, are thought to have involved elements of the Hwasong-17 system.)

March 29, 2022: Briefing the ROK National Assembly, MND claims publicly that March 24’s ICBM test was indeed a Hwasong -15, not -17. (See March 27, above.)

April 1, 2022: ROK Defense Minister Suh Wook stresses that South Korean missiles can “accurately and swiftly strike any targets in North Korea.” Earlier the same day, he vows to develop an “advanced, multilayered missile defense system that the North does not possess.”

April 2, 2022: In her first public comment since Sept., published a day later, Kim Jong Un’s sister Kim Yo Jong castigates South Korea’s defense minister—a “confrontation maniac” and “senseless and scum-like guy”—for “reckless and intemperate rhetoric” about a “preemptive strike” on the DPRK. She concludes: “I will give a serious warning upon authorization. We will reconsider a lot of things concerning south Korea. South Korea should discipline itself if it wants to stave off disaster. I hope I don’t hear him blustering again.” (It is not clear that Suh actually used the word preemptive, though he certainly said strike; see April 1.)

April 4, 2022: Kim Yo Jong repeats her earlier message, only at greater length and naming “So Uk” (Suh Wook), whom she accuses of “abrupt bluffing” and “an irretrievable very big mistake.” She warns: “In case south Korea opts for military confrontation with us, our nuclear combat force will have to inevitably carry out its duty.” Yet she also avers: “We will not fire even a single bullet or shell toward south Korea. It is because we do not regard it as match for our armed forces.” Also, “the north and the south of Korea are of the same nation who should not fight against each other.” She concludes: “I pray that such morbid symptom as feeling threat for no ground would be cured as early as possible.”

April 4, 2022: After Kim Yo Jong’s verbal volleys, MOU “clearly points out that North Korea should not cause additional tension on the Korean Peninsula in any case.” It adds that routine daily inter-Korean phone calls are still taking place as normal.

April 6, 2022: In his last regular press conference as unification minister, Lee In-young urges the incoming administration to adopt a “forward-looking” approach to North Korea. A propos the DPRK’s breaking of its ICBM moratorium, and amid signs of preparations for a fresh nuclear test, Lee says: “We must put an end to this right here.”

April 7, 2022: In an unprecedented move for a president-elect, Yoon Suk-yeol flies by helicopter to Camp Humphreys, the huge USFK headquarters near Pyeongtaek south of Seoul. Sharing a canteen meal with US and ROK troops, he vows to strengthen deterrence against North Korea’s nuclear and missile threats.

April 7, 2022: Unification Minister Lee In-young warns that “April is a time laden with many factors that could lead to the escalation of inter-Korean military tensions.” In strong terms by his standards, he adds: “It is very unfortunate not only for the North but for the future of our nation if (sic) it has chosen nuke (sic) and missiles, disregarding dialogue.”

April 13, 2022: Lee Do-hoon, who served Moon Jae-in as special representative for Korean Peninsula peace and security affairs but switched allegiance to Yoon Suk-yeol, warns the incoming government to be cautious about pursuing sanctions relief: a key goal for Moon, though unachieved. He argues: “Once cash flows into the North, denuclearization will be off the table.” On May 9 Yoon appoints Lee as vice foreign minister.

April 13, 2022: Yoon Suk-yeol nominates Kwon Young-se, a four-term lawmaker and former Ambassador to China, as his first unification minister. Having been confirmed by the National Assembly, Kwon is sworn in and begins work exactly a month later on May 13.

April 14, 2022: Asserting a linkage largely eschewed by Moon Jae-in, MOU nominee Kwon says inter-Korean normalization will be “difficult” as long as Pyongyang continues to build up its nuclear arsenal. He adds: “For sure, (we) will make a request for dialogue.” However, Seoul cannot incessantly dangle “carrots” while continually rebuffed.

April 15, 2022: On Kim Il Sung’s 110th birthday, the ROK government publishes a dossier on the two Koreas’ behind-the-scenes diplomacy prior to their becoming full UN members in 1991. 405,000 pages of diplomatic documents now 30 years old have been declassified.

April 18, 2022: Park Jin, four-term PPP lawmaker nominated to be Yoon’s foreign minister, declares that the new Yoon Suk-yeol administration “will pursue a balanced policy, based on common sense, toward North Korea.” He adds: “ [We] can’t prevent North Korea’s continued provocations only with conciliatory policy…[A] substantial policy change is needed.”

April 19, 2022: MOU says North Korea remains unresponsive to the South’s enquiries about demolition at Mount Kumgang. Citing satellite imagery, Voice of America (VOA) reported that the seven-story floating Haegumgang Hotel has lost half its height, while a golf resort has eight buildings now minus their roofs and outer walls.

April 20, 2022: Lee Sang-min, a researcher at the Korea Institute for Defense Analyses (KIDA), says North Korea might use tactical nuclear arms in a contingency to offset its conventional inferiority. However, US and ROK forces are overwhelmingly stronger.

April 20, 2022: In written answers to lawmakers’ questions ahead of his parliamentary confirmation hearing, Yoon’s MND nominee Lee Jong-sup clarifies: “I am not of the position that the Sept. 19 South-North military agreement should be scrapped.” Rather, he plans to verify if the 2018 accord is being faithfully implemented. As to whether ROK defense white papers should characterize North Korea as a ‘main enemy’: “I will decide carefully.”

April 21, 2022: New MOU nominee Kwon Young-se says resuming Kumgangsan tours is not “a desirable idea in the current situation,” and “won’t be easy as it is subject to sanctions.” He adds that Seoul must “clearly” challenge Pyongyang’s dismantlement of some facilities there. But he also supports humanitarian aid, and opposes any blanket rejection of Moon’s policies.

April 21, 2022: MOU reports a fire at a factory in the former Kaesong Industrial Complex (KIC), shut since 2016. Spotted around 1400 local time, the blaze is extinguished by 1450.

April 22, 2022: MOU says it has asked North Korea, via the inter-Korean liaison line, for further information on the previous day’s fire at the KIC.

April 22, 2022: KCNA reveals that Moon Jae-in wrote Kim Jong Un a personal letter on April 20. Kim sent a reply on April 21, “appreciat[ing] the pains and effort taken by Moon Jae In for the great cause of the nation until the last days of his term of office.” After further pleasantries, KCNA concludes: “The exchange of the personal letters between the top leaders of the north and the south is an expression of their deep trust.” The Blue House confirms the exchange of letters and their warm tenor. Neither side published the letters in full.

April 25, 2022: North Korea stages a nocturnal military parade in Pyongyang. Kim Jong Un’s speech emphasizes the need “for further developing the nuclear forces of our state at the fastest possible speed,” including for a possible “unexpected second mission…at a time when a situation we are not desirous of at all is created on this land.” He does not elaborate.

April 26, 2022: Responding to North Korea’s parade, President-elect Yoon’s transition team says his administration will bolster deterrence and strengthen the US-ROK alliance “while simultaneously developing far-superior military technologies and weapons systems.”

April 26, 2022: Moon urges his successor to work with the US to bring Kim Jong Un’s regime back to talks. Admitting that the North’s ICBM launch in March “crossed a red line” and “may be a sign that [Pyongyang] would end dialogue,” he adds: “I hope North Korea will make a rational choice.”

April 28, 2022: Defector activist group FFNK claims that on April 25-26 it sent 20 large balloons, carrying around 1 million leaflets, across the DMZ into North Korea. Information therein included about Yoon Suk-yeol’s election. Such actions are now illegal; FFNK’s leader Park Sang-hak is on trial for two earlier launches (see Jan. 25 above). MOU says it is investigating, including whether this claimed flight actually happened.

April 28, 2022: MOU responds to Kim Jong Un’s parade speech: “North Korea should stop all acts that heighten tensions, including the advancement of its nuclear capabilities, and…return to the negotiating table.”

April 29, 2022: Family of Lee Dae-jun, the South Korean fisheries official shot and incinerated in Northern waters in September 2020, file suit in Seoul Central District Court against the DPRK government. They seek 200 million won ($159,000) in compensation for mental suffering caused to the deceased’s young son and daughter. MND and the Blue House are appealing a separate court order to disclose all information they possess to the family.

May 4, 2022: Both the outgoing and soon-to-be ROK governments condemn the DPRK’s missile launch today, its 14th this year. The NSC calls on Pyongyang “to stop its actions that pose serious threats.” Yoon’s transition team promises “more fundamental deterrence measures.”

May 4, 2022: Lee Jong-sup, former three-star general who is Yoon’s nominee to be the next Minister of National Defense, tells his parliamentary confirmation hearing that South Korea could be a nuclear target for North Korea.

May 7, 2022: In North Korea’s 15th missile launch this year, the ROK JCS report an apparent submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) test in waters near the east coast city of Sinpo. The projectile flew 600 km, reaching 60 km in altitude. The DPRK’s last SLBM test was in October. The JCS adds that it is “maintaining a full readiness posture.” Incoming National Security Adviser (NSA) Kim Sung-han says the Yoon administration will reassess the DPRK’s WMD threat, to “come up with fundamental measures against North Korea’s provocations and actual deterrence capabilities against its nuclear missile threats.”

May 10, 2022: Yoon Suk-yeol is duly inaugurated as president of the Republic of Korea.

May 11, 2022: Yoon picks Kim Kyou-hyun, a career diplomat and onetime deputy national security adviser, as head of the National Intelligence Service (NIS), succeeding Park Jie-won. Kwon Chun-taek, a former NIS official and diplomat, will be first deputy director: a job largely focused on North Korea. (Some had tipped Kwon for the top job.) Like ministers, Kyou must undergo a parliamentary confirmation hearing, but approval is not mandatory.

May 12, 2022: Sources tell Yonhap that, by order of new Defense Minister Lee Jong-sup to the JCS, the ROK military will revert to calling DPRK missile tests “provocations”: a term eschewed under Moon. Seoul will also refer to “unidentified ballistic missiles” rather than “unidentified projectiles.” In a similar hardening of tone, the presidential National Security Office (NSO) “strongly condemns” Pyongyang’s latest missile launch today, and “deplore[s] North Korea’s two-faced actions” of continuing ballistic missile provocations while neglecting its people’s lives and safety amid a coronavirus outbreak.

May 13, 2022: A day after the DPRK admits an outbreak of COVID-19, President Yoon offers to send COVID-19 vaccines. His spokesperson says: “We will hold discussions with the North Korean side about details.” The North today reports six deaths, and that a total of 350,000 people “got fever in a short span of time,” with 18,000 new cases on May 12 alone; 187,8000 “are being isolated and treated.” However one of Yoon’s officials tells reporters, on background: “We know more than what was announced. It’s more serious than thought.” It cannot be assumed that Pyongyang will accept this and other offers of vaccine aid.