Articles

The main feature of inter-Korean relations in the last four months of 2022 was varied and ever-increasing provocations by Pyongyang. Besides multiple missiles, there were artillery volleys and an incursion by five drones. Kim Jong Un also ramped up his nuclear threats, in theory and practice. A revised law widened the scope of nuclear use, while a new stress on tactical weapons was matched by parading 30 new multiple launch rocket systems (MLRs) which could deliver these anywhere on the peninsula. The government of South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol for his part reinstated officially calling North Korea an enemy, and revived concern with DPRK human rights. As the year turned, his government was mulling retaliation for the drone incursions; that could include scrapping a 2018 inter-Korean military accord, a dead letter now due to Pyongyang’s breaches. With tensions rising, the new year ahead may be an anxious one on the peninsula.

A Provoking Period

A single word sums up inter-Korean relations during the last third of 2022: provocation. Not that provocations—by the usual suspect, usually—are anything new on the peninsula. But rarely if ever has North Korea needled the South so intensely, intently, and systematically as in recent months. Not only did the frequent missile launches seen throughout 2022 continue, but the North added several new twists. These included: a missile fired unprecedentedly close to Southern waters; artillery volleys into coastal seas near the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), on the DPRK side but in clear breach of September 2018’s inter-Korean military agreement; a claimed spy satellite, cheekily taking poor-quality aerial photos of Seoul and Incheon; and then the pièce de résistance, brazenly sending five drones across the DMZ for five hours on Dec. 26.

Figure 1 US F-16’s and B-1B bombers are joined by Republic of Korea F-35A’s in a combined training flight during the joint exervise Vigilant Storm. Photo: US Air Force photo by Staff Sergeant Dwane Young

North Korea would doubtless argue that it is the one being provoked. Thus its largest launch of missiles in a single day—23, on Nov. 2—was a riposte to the largest-ever joint US-ROK aerial exercises, Vigilant Storm. But that in turn was prompted by Pyongyang’s having tested missiles with unprecedented intensity throughout 2022—beginning when Moon Jae-in, the friendliest ROK leader Kim Jong Un could ever hope for, was still in the Blue House.

The North’s Nuclear Threat Goes Local

Of especial concern to South Korea was the North’s heightened emphasis on nuclear weapons—especially “tactical nukes,” as Pyongyang calls them, whose targets are explicitly local. In September, the Supreme People’s Assembly (SPA) passed a new law, replacing a shorter 2013 statute, reaffirming the DPRK’s status as a nuclear weapons state. This codifies the DPRK military’s “right” to launch preemptive nuclear strikes “automatically and immediately” in case of an imminent attack against its leadership or “important strategic objects.”

A defiant Kim Jong Un dared the US to maintain economic sanctions for “a thousand years…There will never be any declaration of ‘giving up our nukes’ or ‘denuclearization,’ nor any kind of negotiations or bargaining…As long as nuclear weapons exist on Earth and imperialism remains…our road towards strengthening nuclear power won’t stop.” In similar vein, as the year ended Kim called South Korea “our undoubted enemy,” adding that this fact “highlights the importance and necessity of a mass-producing of tactical nuclear weapons and calls for an exponential increase of the country’s nuclear arsenal.” He could hardly be clearer.

Yoon on the Back Foot

As doubtless intended, Pyongyang’s persistent provocations put Seoul on the spot. Yoon Suk Yeol—the ROK’s still newish conservative president, who took office in May (as discussed in our last issue)—would rather ignore the North, if only he could. Witness his speech in Sept. to the UN General Assembly (UNGA). In sharp contrast to his liberal predecessor Moon Jae-in, who always bent every foreign ear he could about a Korean peace process which (sad to say) after 2019 existed only in his mind, Yoon’s UN speech made no mention whatever of North Korea or the peninsula, focusing rather on universal and global themes.

Yoon did have some prior policy commitments regarding the North. One might be called, in the spirit of Confucius, “rectification of names.” Early on, his transition team pledged to redesignate North Korea as an “enemy” in the ROK’s next defense White Paper, due out early in 2023. These nomenclature debates have gone back and forth in Seoul, as political winds blow this way and that. In recent times, the Korean People’s Army (KPA) was first called an enemy in a 1995 defense policy paper, a year after a DPRK official had threatened to an ROK counterpart that Seoul could become “a sea of fire.” In 2004, with Kim Dae-jung’s “Sunshine” policy in full swing, this was changed to “direct military threat.” In 2010, after the sinking of the corvette Cheonan and the shelling of Yeonpyeong island, “enemy” was reinstated—until Moon’s presidency (2017-22), when it was removed again. To a neutral observer the E-word seems only accurate, given the Kim regime’s rhetoric and behavior. And whatever drives policy in Pyongyang, it is surely not primarily the shifting nuances of vocabulary in Seoul.

Rights Rhetoric Returns—But to What Avail?

Another left/right touchstone for ROK administrations is DPRK human rights. This reflects a practical crux. Engaging North Korea is hard enough, and raising human rights concerns is a sure way to kill dialogue before it even starts. Hence, pro-engagement Southern leaders like Moon and the late Kim DJ tried to avoid the topic. If perhaps understandable as a pragmatic stance, Moon took this to extremes: treating ROK activists for DPRK human rights as the enemy, or so they felt. Such NGOs were glad to see Yoon replace Moon.

Yet how much will change? Not only is Pyongyang wholly unresponsive, but domestically Moon’s Democratic Party (DPK) still controls the National Assembly and can thus continue to block the North Korean Human Rights Act (NKHRA), enacted in 2016 under Moon’s conservative predecessor Park Geun-hye. This has several provisions, few of which have yet come to pass owing to DPK obstruction. Thus MOU is enjoined to report annually on DPRK human rights. (In truth, it’s hard to see what this could add to other efforts already ongoing; above all the excellent and comprehensive White Papers produced every year since 1996 by another ROK government body, the Korean Institute for National Unification (KINU)). The Ministry has duly complied, but under Moon its reports languished unpublished, ostensibly to protect defectors’ data. Now, under Yoon, a white paper will be issued later this year.

The NKHRA also mandated that a foundation on DPRK human rights be set up. That remains stillborn, as the DPK has refused to nominate members to its board. It is unclear if they will relent, or whether some other way can be found. (A separate problem is that public opinion in South Korea is surprisingly indifferent to such issues, perhaps jaded by their intractability.)

Externally, Yoon is less constrained. In November the ROK once again joined other democracies in co-sponsoring a UN draft resolution condemning North Korea’s human rights, after four years when the Moon administration shunned such initiatives. In December, the ROK’s envoy to the UN for the first time highlighted the specific plight of female defectors: an implicit dig at China, where most of their suffering (forced marriages, trafficking, refoulement, etc) takes place. The bitter truth is that outsiders, including ROK governments of whatever stripe, are impotent to improve human rights in the DPRK.

Leaflets and Drones: Will Yoon Make a U-Turn?

Elsewhere, what Seoul decides to do does make a difference. Sending balloons with leaflets and other materials across the DMZ into North Korea is a case in point. Under strong pressure from Pyongyang—which all else aside, ludicrously claims that this is how COVID-19 got into the North—Moon controversially banned such actions — to little effect, since militant activist groups like Fighters For A Free North Korea (FFNK) have carried on regardless.

Where does Yoon stand? Although most conservatives criticized the ban, initially the new government continued to try to dissuade the likes of FFNK, at least verbally. Yet in a striking intervention in November, Minister of Unification Kwon Young-se filed a court opinion claiming the leaflet ban is unconstitutional. Presumably this is now the official view. Since the DPK’s grip on Parliament means the legislation cannot be amended as such, all eyes are on the Constitutional Court, which will rule on the issue in the coming months.

Meanwhile the North’s brazen drone infiltration in December, discussed below, is hardening attitudes in Seoul. With Yoon’s expressed enthusiasm—psychologically understandable, but arguably imprudent—for tit-for-tat retaliation, in early 2023 floating leaflets across the DMZ seems no longer such a big deal, and maybe not even a bad idea. As Yoon mulls whether to suspend 2018’s inter-Korean military accord, given the North’s repeated violations, MOU has said it is reviewing whether in that case it could legally resume propaganda broadcasts at the border or send leaflets. Sensing the new mood, FFNK said in January that it will use drones rather than balloons to carry leaflets into North Korea “at the earliest date possible”; MOU asked them not to. At this rate the skies over the DMZ may get busy, and dangerous, in 2023.

A Plethora of Provocations

Which brings us to Pyongyang’s provocations. December’s drones were the climax of a long and tiresome autumn and winter, when the North piled on pressure, pushed the envelope and crossed red lines on multiple fronts. What follows may not be a complete account, but will illustrate the overall process and its cumulative nature.

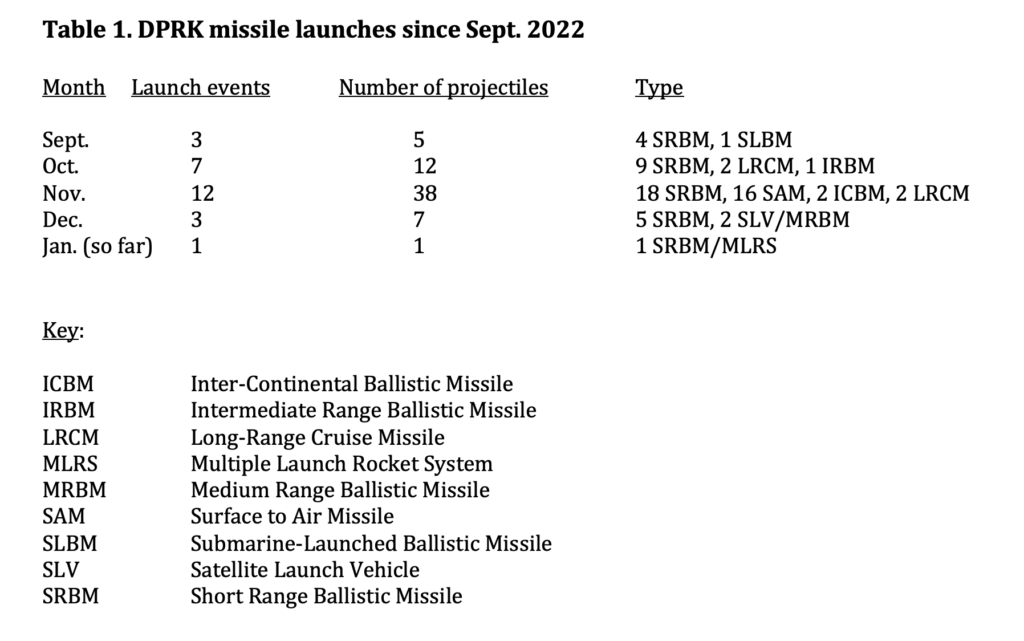

In the beginning were missiles, and ever shall be. 2022 was a record year for DPRK missile tests, with over 90 projectiles launched: four times the previous maximum. That is about one-third of all the missiles North Korea has launched in its entire history—three-quarters of which have been since Kim Jong Un inherited power in late 2011. During the period under review, the monthly tally was as shown in Table 1. November was the peak, including as it did two highlights: the first successful test of North Korea’s and the world’s largest missile, the Hwasong-17; and a record 23 missiles in one day on Nov. 2, mostly non-ballistic SAMs.

Table 1 DPRK missile launches since September 2022. Source: NK News

Pyongyang began ramping up pressure against Seoul in October, at first in a fairly low-key manner. On Oct. 12, what official media called “two long-range strategic cruise missiles…for the operation of tactical nukes” flew for 2,000 km in oval and figure-of-eight pattern orbits, over DPRK territory; both “clearly hit the target.” A day later, South Korea scrambled F-35A fighters after a dozen KPA warplanes flew unusually close (about 25 km) to the DMZ, and closer still (12 km) to the Northern Limit Line (NLL, the de facto inter-Korean marine border which Pyongyang officially purports not to recognize).

Also on Oct. 13, KPA coastal artillery fired 170 rounds on the west and east of the peninsula, again near the DMZ; a further volley of 250 rounds followed on Oct. 18. Though all these shells landed in Northern waters, this was a clear breach of September 2018’s inter-Korean military accord—the sole lasting outcome of 2018’s North-South summitry. Then on Oct. 24 the ROK Navy fired warning shots after a DPRK merchant ship crossed the western NLL, a deliberate incursion, in Seoul’s view. The Northern navy fired 10 rounds in response.

More shelling (100 rounds, east coast) followed on Nov. 2. That was a side-dish compared to the main course that day. North Korea launched 23 missiles, in four tranches, from multiple locations and in several directions into both the West (Yellow) Sea and East Sea (Sea of Japan). For the first time ever, one of these landed close to ROK waters—prompting an air-raid warning on Ulleung-do, a Southern island toward which it had seemed to be heading.

Much Ado about NADA

November continued to be busy with missile launches (see Table 1). The following month brought two fresh twists. On Dec. 19 KCNA, North Korea’s official news agency, reported that a day earlier the National Aerospace Development Administration (NADA) had “conducted an important final-stage test for the development of [a] reconnaissance satellite.” As proof, it published aerial photographs of Seoul and the port city of Incheon. That was cheeky—and unwise. In grainy black and white, both images were crude and blurry. (Cautious ROK media blurred them further, evidently not trusting the Yoon administration’s occasional hints—not yet delivered on—that it plans to lift the longstanding ban on viewing DPRK materials.) Most comment in South Korea was skeptical and derisive. Were these really satellite photos? Or if that’s the best Kim Jong Un’s space spyware can do, the South has little to fear. (The ROK’s elegant riposte, a couple of days later, was to publish a far superior image from its own spy satellite, in color and high resolution, of Kim Il Sung Square in Pyongyang.)

Figure 2 Kim Yo Jong, sister of North Korean leader Kim Jong Un making a speech in Pyongyang on Aug. 10, 2022. Photo: KCNA via AP

Southern mockery prompted an astonishing outburst from Pyongyang. Granted, outbursts are a DPRK specialty—but not like this. In her brief career hitherto (with many years yet to come, perhaps) as a quasi-official spokesperson, or more exactly a commenter, Kim Jong Un’s sister Kim Yo Jong has struck a new note: more informal and personal than the standard turgid North Korean boilerplate, if often no less angry or nasty. In November she had already insulted Yoon, briefly but sharply (see Appendix). This time she threw a hissy-fit with a long plaintive rant, whose executive summary might be: “How DARE you?” It begins: “I am getting bored and tired of hearing the bark of the south Korean puppets who have the bad habit of finding fault with others,” continuing in that vein for almost 2,000 words. Her sole factual point, or claim, seems to be that obviously the DPRK wouldn’t fit an expensive hi-res camera that would only be used once; that wasn’t what this launch was about.

While that begs many technical questions, the politics are crystal clear. The First Sister, and maybe her brother too, are humiliated and furious. Nothing worse than being sneered at by those snooty Southern puppets. That wasn’t the reaction they intended at all. One can only fear for whoever, in NADA or KCNA or more likely their Party bosses, thought it a great idea to publish those scuzzy photos. Unless, of course, it was Kim Jong Un himself.

An Unwelcome Christmas Gift

The most significant event in the period under review came at the very end of the year. On Dec. 26, North Korea raised the ante in its campaign of provoking the South. In the most blatant violation yet of 2018’s inter-Korean military agreement, Pyongyang sent five unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs, i.e. drones) across the DMZ into South Korea. No concrete harm was done, but the embarrassment could hardly have been greater. Despite firing over 100 rounds, the ROK military failed to down any of the intruders; they are presumed to have returned unscathed to base. Apologizing, a red-faced Ministry of National Defense (MND) claimed that they “flew on aberrant trajectories, changing flight speed and altitudes in unexpected ways.” South Korea retaliated by sending a drone of its own into North Korea.

Adding insult to injury, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) initially dismissed as “untrue and groundless” claims that one drone breached the no-fly zone around the new presidential office that Yoon has carved out within MND’s compound at Yongsan in central Seoul (replacing the perfectly serviceable but less central Blue House). But on Jan. 5 the JCS admitted that this breach did indeed happen, while insisting it posed no concrete risk to security.

Disarray and disputes over this continued in Seoul as Comparative Connections went to press, with neither military nor political circles smelling of roses. On the military side, there seem to have been at least two worrying delays. The drones were not detected until 1019, six minutes after they had crossed the MDL. And even when belatedly apprised of the incursion by the frontline First Army Corps, the JCS was slow to pass it on to the Capital Defense Command (CDC)—which therefore could not take immediate action against the P-73 penetration.

Regrettably but predictably, given the entrenched hostility between the two main parties, this rapidly became a political football. The DPK called the sending of a tit-for-tat drone a reckless act which served only to obfuscate Pyongyang’s culpability. With the UN Command (UNC) beginning its own probe, it is not impossible (as has happened before) that both sides may be found to have breached the 1953 Armistice. An indignant MND insisted the ROK has the right to defend itself, and that its response was proportionate.

Not for the first time, Yoon’s government seemed as keen to hunt down leakers as to tackle the issues they revealed. Suspicions that one drone had penetrated further than was initially admitted were first aired by Kim Byung-joo, a four-star general turned DPK lawmaker, on Dec. 28. After the JCS changed its tune, some in the ruling camp wondered how Kim could have known. Shin Won-sik, another ex-general (three-star) and a former head of the CDC who went into politics on the other side (in Yoon’s ruling conservative People Power Party, PPP), said he could not shake off the “reasonable doubt that Rep. Kim may have communicated with North Korea.” Kim batted off this smear: “Anyone can easily infer the infiltration based on a 30-minute flight tracking.” A luta continua.

Prospects for 2023

An unhappy New Year is hardly a new experience for the peninsula. Yet 2023 looks bleaker than most. While as usual the original sin is North Korea’s, risk derives from both sides. Having abandoned all pretense of interest in serious dialogue about anything with anyone—not just Yoon and South Korea, but also Biden and the US—Kim Jong Un is openly doubling down and ramping up. Relentless missile testing, the new emphasis on tactical nuclear weapons, and now drone incursions, all bespeak a regime intent on prodding and provoking. The $64,000 question—what does Kim really want?—remains as clear as mud. But evidently it is not Yoon’s “audacious offer,” any more than it was Moon Jae-in’s vaunted peace treaty.

Figure 3 North Korean leader Kim Jong Un watches a missile launch in this image released by the state-run Korean Central News Agency on Oct. 10, 2022. Photo: KCNA via Reuters

The risk is twofold: not just what Kim might do, but also how Yoon may react. He is still new in post, and lacks political or military experience. Like many on the Right, his talk is hawkish. North Korea always tests conservative ROK leaders. As we recorded at the time, in 2010 Lee Myung-bak faced two attacks: the sinking of the frigate Cheonan and the shelling of Yeonpyeong island: 50 South Koreans died. In 2015 it was Park Geun-hye’s turn, with a mine that maimed two ROK soldiers in the DMZ. Both presidents reacted with commendable restraint, and so peace was kept on the peninsula.

Does Yoon have that cool a head? His stress on tit-for-tat retaliation, fair enough for a drone incursion, could be far riskier in a more serious DPRK aggression. In such a scenario it is crucial that any military riposte should not escalate matters out of hand. No doubt more seasoned advisers will urge caution, but—while not envying his predicament one bit—I fear that the angry urge to strike back might overrule that, with incalculable consequences.

Chad O’Carroll, founder and CEO of NK News, is similarly concerned. In a recent article he gloomily regards it as “quite possible that South and North Koreans will die in a direct but limited military confrontation in the year ahead.” He goes on: “2023 will be a very turbulent year, with the strong possibility of limited inter-Korean military violence in the event of an accident, miscalculation or hot-headedness on either side of the peninsula.” Living as he does in Seoul, I’m sure he hopes to be wrong. But look at the sky; storm clouds are gathering.

Appendix: Kim Yo Jong’s Press Statement, 24 Nov. 2022

Pyongyang, November 24 (KCNA) — Kim Yo Jong, vice department director of the Central Committee of the Workers’ Party of Korea (WPK), released the following press statement on Nov. 24:

On Nov. 22, the foreign ministry of south Korea described the DPRK’s exercise of the right to self-defence as “provocation,” announcing that it is examining its additional “independent sanctions” as the “provocation” continues.

As soon as the U.S. talked about its “independent sanctions” against the DPRK, south Korea parroted what the former said. This disgusting act shows more clearly that the south Korean group is a “faithful dog” and stooge of the U.S.

Such frequent acts of the south Korean stooges dumbfound me.

I wonder what “sanctions” the south Korean group, no more than a running wild dog on a bone given by the U.S., impudently impose on the DPRK. What a spectacle sight! [sic]

If the master and the servant still attach themselves to the useless “sanctions,” we will let them do that one hundred or thousand times.

If they think that they can escape from the present dangerous situation through “sanctions,” they must be really idiots as they do not know how to live in peace and comfort.

I wonder why the south Korean people still remain a passive onlooker to such acts of the “government” of Yoon Suk Yeol and other idiots who continue creating the dangerous situation.

Anyhow, Seoul had not been our target at least when Moon Jae In was in power.

We warn the impudent and stupid once again that the desperate sanctions and pressure of the U.S. and its south Korean stooges against the DPRK will add fuel to the latter’s hostility and anger and they will serve as a noose for them.

www.kcna.kp (Juche111.11.24.)

Sept. 2, 2022: Uriminzokkiri, a DPRK website for external consumption, lambastes the just-ended Ulchi Freedom ShieldUS-ROK military exercises as “an extremely hostile and anti-national hysteria and an unprecedented military provocation. The Yoonites [sic: the ROK President is Yoon Suk Yeol] who spit out hostile remarks and run wild to ignite an aggressive war are the villains against peace and security in the Korean Peninsula.”

Sept. 3, 2022: Korea Global Forum for Peace (KGFP), a big international conference hosted by South Korea’s Ministry of Unification (MOU) on Aug. 30-Sept. 1, admits that it suffered a data breach on Aug. 29 where attendees” personal data was leaked. No fingers are pointed, but North Korean hackers are increasingly targeting DPRK-watchers, among others.

Sept. 4, 2022: In its first commentary on Ulchi Freedom Shield (albeit not carried in domestic media such as Rodong Sinmun), the DPRK’s official Korean Central News Agency (KCNA) publishes the full 3,400-word text of a “research report” by the “Society for International Politics Study.” Surveying 70 years of US-ROK joint military maneuvers—or in their words, “Aggressive War Drills Lasting on Earth in Longest Period” (sic)—this warns that “the possibility of a nuclear war on the Korean Peninsula is now becoming a present-tense matter.”

Sept. 5, 2022: ROK military authorities say Pyongyang appears to have again opened the floodgates at its Hwanggang dam without notifying Seoul, as inter-Korean accords stipulate it must. The North did the same in late June and early August. MOU says that during today’s regular call on the inter-Korean hotline, it tried to deliver a formal reminder of the need for advance notice. However, “the DPRK [sic] ended the call without clarifying its position.”

Sept. 5, 2022: Park Sang-hak, head of the militant activist group Freedom Fighters for North Korea (FFNK), says his group conducted another balloon launch, their fourth since July 6. “We sent 20 balloons to the North from Ganghwado…on Sept. 4 loaded with 50,000 tablets of Tylenol [painkillers], 30,000 tablets of vitamin C supplements and 20,000 masks to help North Korean compatriots who are suffering from COVID-19.” One balloon carries large pictures of Kim Jong Un and Kim Yo Jong: the caption calls for their extermination.

Sept. 7, 2022: MOU says it has approved an NGO’s application to send “nutritional” aid to North Korea. No further details are revealed. This is its eighth such approval this year, and the first under Yoon. With DPRK borders still largely closed, and amid icy North-South ties, it is unclear how much of this has been delivered.

Sept. 7, 2022: 14th Supreme People’s Assembly (SPA), North Korea’s rubber-stamp Parliament, opens its 7th session: the second this year.

Sept. 8, 2022: SPA passes a new law, replacing a shorter 2013 statute, reaffirming the DPRK’s status as a nuclear weapons state. (See main text for fuller details).

Sept. 8, 2022: SPA passes a new law, replacing a shorter 2013 statute, reaffirming the DPRK’s status as a nuclear weapons state. Inter alia, this codifies the DPRK military’s “right” to launch preemptive nuclear strikes “automatically and immediately” in case of an imminent attack against its leadership or “important strategic objects.” A defiant Kim Jong Un dares the US to maintain economic sanctions for “a thousand years…There will never be any declaration of “giving up our nukes” or “denuclearization,” nor any kind of negotiations or bargaining…As long as nuclear weapons exist on Earth and imperialism remains…our road towards strengthening nuclear power won’t stop.”

Sept. 8, 2022: On the eve of the Chuseok (harvest festival) holiday, Unification Minister Kwon Young-se proposes talks on family reunions. With those affected now in their 80s and 90s, “(we) have to resolve the problem before the word ‘separated family’ itself disappears …(the two sides) should map out swift and fundamental measures, using all available methods.” He adds that one-off events for a few families are not enough; those have been held on 22 occasions, most recently in 2018. Seoul is ready to discuss this issue anytime, anywhere and in any format; it is trying to convey that offer formally to Ri Son Gwon, who as head of the United Front Department (UFD) of North Korea’s ruling Workers” Party (WPK) is Kwon’s Northern counterpart—via the inter-Korean liaison hotline.

Sept. 19, 2022: Seoul Central District Prosecutors Office interrogates former Deputy National Security Adviser Kim You-geun over his role in the unprecedented repatriation in Nov. 2019 of two Northern fishermen (who had reportedly confessed to murdering 16 shipmates).

Sept. 19, 2022: MOU Kwon urges Pyongyang to stop “distorting and denigrating” President Yoon’s “audacious plan” to assist the North if it denuclearizes. Better to start a “virtuous circle” and return to dialogue based on “mutual respect and benefit.”

Sept. 19, 2022: Gen. Kim Seung-kyum, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS), tells the ROK National Assembly: “I will make North Korea clearly realize that should it attempt to use nuclear arms, it would face the overwhelming response from the South Korea-US alliance and our military, and there would be no scenario for regime survival anymore.”

Sept. 20, 2022: Relatedly, prosecutors question Kim Yeon-chul, unification minister at the time. He is accused of cutting short an inquiry into the case and ordering the deportation.

Sept. 20, 2022: Yoon Suk Yeol addresses UN General Assembly (UNGA). Unusually, and in contrast to his predecessor Moon Jae-in, he makes no mention of North Korea or peninsular issues; focusing instead on universal global themes (his speech is titled “Freedom and Solidarity: Answers to the Watershed Moment.’)

Sept. 22, 2022: A poll of 1,200 adults by Seoul National University (SNU)’s Institute for Peace and Unification Studies (IPUS) finds record numbers skeptical that North Korea will ever denuclearize (92.5% deem this “impossible”). A majority—55.5%, the most since the poll started in 2007—support South Korea having its own nuclear weapons. 60.9% think the North may engage in armed provocations. 31.6% reckon Korean unification is impossible, but almost half (46%) consider it necessary.

Sept. 23, 2022: Ahead of North Korea Freedom Week (Sept. 25-Oct 1), MOU urges activist groups to refrain from sending leaflets and other materials across the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) by balloon. It also warns of “strong and stern” action, should Pyongyang carry out its threat to retaliate against such activities.

Sept. 25, 2022: CNN airs interview with Yoon Suk Yeol, made when he was in New York for the UNGA. Yoon opinesthat “in case of military conflict around Taiwan, there would be increased possibility of North Korean provocation…in that case, the top priority for Korea and the US-Korea alliance on the Korean Peninsula would be based on our robust defense posture. We must deal with the North Korean threat first.”

Sept. 27, 2022: Activist ROK NGOs urge the liberal opposition Democratic Party (DPK) to stop blocking an official North Korean Human Rights Foundation (NKHRF). The 2016 act establishing this, passed during Park Geun-hye’s presidency, requires the two main parties to each recommend five candidates to the board. The DP, which took power in 2017 and still controls parliament, has refused to nominate anyone—thus rendering the NKHRF stillborn.

Sept. 28, 2022: After a parliamentary briefing by the National Intelligence Service (NIS), ROK lawmakers leak tidbits to local media. The NIS reckons the DPRK may test a nuclear device between Oct. 16 and Nov. 7 (it does not). Leader Kim Jong Un “appears to be showing no signs of health issues and returned to weighing between 130 and 140 kilograms.”

Oct. 4, 2022: After launching an intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) earlier that day, North Korea does not respond to the South’s daily 9 am call on their liaison hotline. This prompts fears in Seoul that Pyongyang has cut off contact, as in the past. The North answers normally when contacted at 5 pm. As a separate military hotline remained in operation, technical rather than political problems are suspected (e.g. rain damage).

Oct. 7, 2022: Asked by reporters whether North Korea’s incessant missile testing might lead Seoul to scrap Sept. 2018’s inter-Korean military accord, as hinted at by Defense Minister Lee Jong-sup, President Yoon says: “It’s a bit difficult to tell you in advance.”

Oct. 10, 2022: After an especially intense flurry of weapons testing from Sept. 25 through Oct. 9, KCNA explains what this was all about: “Respected Comrade Kim Jong Un Guides Military Drills of KPA Units for Operation of Tactical Nukes.” Kim says DPRK forces are “completely ready to hit and destroy targets at any time from any location.”

Oct. 10, 2022: Responding to Kim’s nuclear braggadocio, the ROK presidential office calls the security situation on the peninsula “grave.”

Oct. 11, 2022: President Yoon says North Korea “has nothing to gain from nuclear weapons.”

Oct. 12, 2022: Chung Jin-suk, interim leader of the ROK’s conservative ruling People Power Party (PPP), says that if North Korea carries out a new nuclear test, the South should scrap 1991’s inter-Korean declaration on denuclearization—which he says Pyongyang has turned into “a piece of waste paper.”

Oct. 14, 2022: A propos recent DPRK artillery fire into (its own) coastal waters close to the DMZ, President Yoon says“it’s correct that it’s a violation of the Sept. 19 [2018] accord.”

Oct. 14, 2022: In response to Pyongyang’s missile tests and its emphasis on tactical nukes, Seoul sanctions 15 North Korean individuals and 16 DPRK institutions, the ROK’s first such sanctions since 2017, and the first by Yoon; there were none during Moon Jae-in’s presidency. The move is symbolic, given the lack of inter-Korean commerce.

Oct. 18, 2022: Amid reports that the DPRK has dismantled more ROK-built and –owned facilities at the former Mount Kumgang resort—specifically, a sushi restaurant—MOU calls this “a clear violation of inter-Korean agreements” and urges the North to stop.

Oct. 20, 2022: After further volleys from Korean People’s Army (KPA) artillery into what the 2018 North-South military accord designated as no-fire maritime buffer zones near the inter-Korean border, Seoul calls on Pyongyang to respect that agreement and desist.

Oct. 21, 2022: Meeting with relatives of two South Koreans detained in North Korea, MOU Kwon says: “The government will do its best to win [their] release by mobilizing all available means.” Pyongyang is known to have held six ROK citizens since 2013. Three are pastors, all serving hard labor for life for alleged espionage. The other trio are former defectors. Their prospects are bleak.

Oct. 21, 2022: In a UN Security Council (UNSC) meeting on women, peace and security, ROK Ambassador Hwang Joon-kook highlights the “appalling and heartbreaking” plight of female escapees from the DPRK. Risks they face include human trafficking, imprisonment, and harsh punishment if repatriated. Seoul has not raised this issue officially before. This is an implicit criticism of China, where all these abuses (including refoulement) occur.

Oct. 24, 2022: Two Koreas exchange warning shots before dawn in the Yellow Sea, after a DPRK merchant ship briefly crosses the Northern Limit Line—NLL, the de facto inter-Korean marine border—near Baengnyeong Island. The North, which does not recognize the NLL and claims waters south of it, accuses a Southern warship of intruding. Pyongyang also says the South has resumed propaganda broadcasts at the DMZ, which Seoul denies.

Oct. 26, 2022: ROK Defense Minister Lee Jong-sup declares: “it’s time to change our strategy” toward the DPRK nuclear threat. Rather than seeking to curb Pyongyang’s WMD development, Seoul should focus on deterrence, to convey “a clear sense that if North Korea attempts to use nuclear weapons, it will bring about an end to [their] regime and it will disappear completely.”

Oct. 30-Nov. 5, 2022: US and ROK hold their largest ever joint aerial exercise, Vigilant Storm. Over 240 aircraft, including some of the most advanced they possess, fly 1,600 sorties.

Nov. 2, 2022: In response to Vigilant Storm, the DPRK launches a record 23 missiles. For the first time, one lands near ROK territorial waters, prompting an air raid alert on Ulleung island in the East Sea/Sea of Japan, where it had seemed headed. The JCS condemns this as “very rare and intolerable.” Calling an emergency meeting of the National Security Council, President Yoon says it was “effectively a violation of our territory.” He orders that “strict measures be taken swiftly to ensure North Korea pays a clear price for its provocation.”

Nov. 10, 2022: Civic groups opposed to the law that prohibits sending leaflets into North Korea reveal a powerful ally. In an opinion submitted to the Constitutional Court, which is reviewing the matter after a petition by 27 NGOs, MOU Kwon Young-se says that the ban “goes against the Constitution because it infringes on freedom of expression.” Kwon also criticizes the law’s vague wording, which could be enforced “arbitrarily.”

Nov. 11, 2022: MOU says it is trying to return the body of a presumed North Korean woman (she was wearing a badge of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il), retrieved from the Imjin river on July 23. Pyongyang is not responding, which is unusual in these cases. Since 2010 Seoul has repatriated 23 such corpses, carried down-river across the DMZ; the last was in Nov. 2019.

Nov. 15, 2022: South Korea’s Education Ministry (MOE) says that an advisory committee, formed since Yoon Suk Yeol took office, has recommended 90 changes to social studies text books approved for fifth and sixth grades “due to errors or possible ideological bias.” One publisher has already agreed to alter the phrase “DPRK government” to “DPRK regime.”

Nov. 16, 2022: For the first time since 2017, South Korea joins other democracies in in co-sponsoring the UN’s annual resolution highlighting DPRK human rights concerns. North Korea accuses the South of seeking to distract attention from the recent deadly crowd crush in Seoul. (This is Pyongyang’s first mention of the Itaewon tragedy: no condolences were sent.)

Nov. 16, 2022: Headlined “Fugitive underwear boss gave Kim Jong-un Hermès saddle, say prosecutors,” the JoongAng Daily publishes “exclusive” about Kim Seong-tae, ex-chairman of SBW (Ssangbangwool) Group. Besides that luxury saddle, in 2019 Kim allegedly sent $1.5 million to DPRK representatives in China, apparently hoping for business opportunities. (On Jan. 10 Kim was arrested in Thailand, so further revelations may follow.)

Nov. 17, 2022: PPP leader Chung Jin-sook claims the Ssangbangwool case “is developing into a bribery scandal involving North Korea and the Moon Jae-in administration,” which “should be held accountable.” Saying SBW sent as much as $7 million to Pyongyang, Chung reckons the government and NIS must have known. But he cites no evidence.

Nov. 17, 2022: Interviewed by Yonhap, MOU Kwon insists that “the goal of denuclearizing North Korea is not unattainable.” “Extended deterrence, sanctions and pressure” can make the DPRK return to talks. He adds that while Seoul does not seek its own bomb, or to reintroduce US tactical nukes, those stances could alter if tensions worsen and public opinion shifts.

Nov. 21, 2022: MOU releases a booklet fleshing out President Yoon’s “audacious plan” in a bit more detail. This lays out three stages of gradually increasing South Korean assistance if North Korea undertakes denuclearization, but is vague on what exactly the North has to do to unlock each stage. There is no prospect anyway of this coming to pass.

Nov. 24, 2022: Kim Jong Un’s sister Kim Yo Jong issues second press statement in three days (the first condemned the UNSC for “double standards” in discussing the DPRK’s most recent ICBM launch). This one lays into “the south Korean stooges” for being “a running wild dog on a bone given by the US,” castigating “Yoon Suk Yeol and other idiots” as “impudent and stupid.” Menacingly, she adds: “Anyhow, Seoul had not been our target at least when Moon Jae In was in power.” (For full text, see the Appendix.)

Nov. 24, 2022: MOU responds with dignity and restraint: “We consider it very deplorable that Vice Director Kim Yo-jong criticized the leader of our country with vulgar language today without showing even the most basic level of courtesy.”

Nov. 30, 2022: A new booklet from Pyongyang Publishing House, “The Gallop To Ruin,” denounces Yoon Suk Yeol as a “political moron” who “cannot escape a violent death.”

Dec. 2, 2022: For the second time in as many months the ROK imposes its own sanctions, targeting eight persons and seven agencies seen as complicit in the DPRK’s WMD programs. Of the individuals, six work for three North Korean banks; the other two are from Singapore and Taiwan. The US and Japan also impose similar bilateral sanctions.

Dec. 6, 2022: “Sources” tell Yonhap that the next biennial ROK defense White Paper, due out in January, will again designate the DPRK regime and military as an “enemy,” fulfilling a pledge by Yoon Suk Yeol’s transition team before he took office. Troop education materials have already revived the E-word, banished under Moon Jae-in in his quest for peace.

Dec. 7, 2022: ROK DM Lee tells a “forum on the military’s spiritual and mental force enhancement” that South Korean troops “should clearly recognize as our enemy the North Korean regime and [its] military,” given the North’s provocations and threats.”

Dec. 7, 2022: At a ceremony promoting 18 brigadiers-general (one star) to lieutenant general (three stars), President Yoon says that despite North Korea’s nuclear arsenal, the South must “perfectly overwhelm” it in conventional military strength.

Dec. 9, 2022: At a virtual meeting of the Greater Tumen Initiative (GTI), South Korea calls on the North to return to this UN-backed intergovernmental cooperation mechanism, set up in 1995. Current members are China, Russia, Mongolia. and the ROK. The DPRK pulled out in 2009 in protest at UNSC sanctions. From July Seoul will chair the GTI for three years.

Dec. 9, 2022: ROK Vice Unification Minister Kim Ki-woong says the Yoon government will map out a three-year blueprint to improve North Korean human rights.

Dec. 15, 2022: MOU says that since Sept. 2021 three (unnamed) NGOs have sent soybean oil worth 1.2 billion won ($922,000) to North Korea, under a government program “to offer nutritional aid to the North amid chronic food shortages and the COVID-19 pandemic.” Two of the shipments were since Yoon took office.

Dec. 19, 2022: KCNA reports that on Dec. 18 the DPRK National Aerospace Development Administration (NADA) “conducted an important final-stage test for the development of [a] reconnaissance satellite.” It publishes grainy black and white aerial views of Seoul and Incheon. Seoul queries whether such “crude” low-resolution images are really from a satellite, suggesting the North still has far to go technically. NADA says it will launch a military reconnaissance satellite by April.

Dec. 20, 2022: Kim Yo Jong loses it, issuing a furious, lengthy (1,900 words) rant against those in Seoul “who have tongue belittled [sic] our yesterday’s report on an important test for developing a reconnaissance satellite.” Though mainly invective, her point seems to be that a hi-res camera would have been a waste of money, as Dec. 18’s test prioritized other aspects.

Dec. 26, 2022: Five DPRK unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs, aka drones) cross the DMZ and fly over South Korea for almost five hours. One reaches northern Seoul. The ROK military fails to shoot down any, and loses radar contact. Next day military authorities apologise. The South retaliates by sending drones of its own over North Korea; details are not given.

Dec. 26-31, 2022: As in recent years, North Korea closes the year with a big Party meeting: the 6th Enlarged Plenum of 8th WPK Central Committee. The main focus is military, with tough language even by DPRK standards. Calling South Korea “our undoubted enemy.” Kim Jong Un says this “highlights the importance and necessity of a mass-producing of tactical nuclear weapons and calls for an exponential increase of the country’s nuclear arsenal.”

Dec. 28, 2022: MND says that in 2023 the ROK will spend 560 billion won ($441 million) on improving its defenses against drones.

Dec. 29, 2022: South Korea holds large-scale anti-drone military drills, apparently for the first time since 2017.

Dec. 31, 2022: A ceremony to hand over 30 new “super-large multiple rocket launchers” to the WPK—not to the KPA, note—is held “with splendor” outside Party headquarters. Congratulating munitions workers, Kim Jong Un exults at these weapons systems: “Comrades, have a look at them. I really feel invigorated.”

Jan. 4, 2023: Yoon’s spokesperson says he has “instructed the National Security Office to consider suspending the Sept. 19 (2018) military agreement in the event North Korea carries out another provocation violating our territory.” Yoon also “instructed” DM Lee to beef up the ROK’s military drone capacity. His office says the North has “explicitly” violated the 2018 accord 17 times since October.

Jan. 5, 2023: Amplifying the above, ROK media cite unnamed officials as warning that Seoul may suspend not only the military pact but also 2018’s inter-Korean joint declaration, should Pyongyang again intrude on its territory. A “key presidential official” tells Yonhap: “It’s part of our sovereignty to invalidate inter-Korean agreements if circumstances change.” Hinting at a major policy shift, MOU says it is reviewing whether it could legally resume propaganda broadcasts or sending leaflets if these agreements were suspended.

Jan. 9, 2023: South Korea’s presidential office says that last year it granted a meeting request by North Korea human rights activists, including FFNK, and is “keeping the channel open.” Under Yoon’s predecessor Moon the Blue House shunned such groups as hostile.

Jan. 9, 2023: NK News reports that the United Nations Command (UNC) has set up a Special Investigation Team to probe whether recent drone flights over the Military Demarcation Line (MDL) violated the Armistice. That could mean the ROK as well as the DPRK launches.

Jan. 9, 2023: ROK media report that three persons on Jeju island, linked to the small leftist Progressive Party and the Korean Peasants’ League, are under police investigation for running a pro-North underground group since 2017, directed by DPRK agents. The accused deny the charges and refuse the NIS summons. A separate probe into another pro-Pyongyang network has led to raids in Jeju, Seoul, South Gyeongsang and North Jeolla.