Articles

Australia’s politicians prepare for the national election that must be held by May. In judging the first term of Anthony Albanese’s Labor government, the key concern for Australia voters is the cost of living, while international issues are bracketed by the United States and China—the return of President Donald Trump and the cooling of China’s trade coercion of Australia. The Albanese government tells Australians they face “fraught and fragile global conditions” in a “a time of great global uncertainty,” in “the most complex and challenging strategic environment since the Second World War.” Canberra’s approach to the Trump administration will emphasize traditional alliance ties while reinforcing new elements: AUKUS nuclear submarines, the Quad, the increase of US forces on Australian soil, and steps toward free trade in defense equipment and technology to achieve more integration between US and Australian industries.

Australia’s Election, Trump’s US Election

One of the many unusual impacts of Trump’s return to the presidency is the influence he will have on the federal election Australia will hold by May 2025. Prime Minister Albanese choses the day, but the three-year federal election cycle means the latest date for the vote on the House of Representatives and half the Senate is May 17, 2025. The parliamentary sitting calendar for 2025 is shaped by the election deadline. Australia’s annual budget is usually presented to Parliament in May. But the date for the 2025 budget is brought forward to March 25, 2025. An early budget and then a May federal poll is the same timetable used by Scott Morrison’s Liberal-National Coalition government in the previous elections in 2019 and 2022.

Issues that resonated in the US election will echo in Australia—the cost of living, housing, and migration levels. The opposition leader Peter Dutton will mobilize an Australian version of the question Trump asked US voters: “Are you better off than you were three years ago?” Labor’s response will be to ask voters: “Who is going to make you better off in the next three years?”

Figure 1 U.S. President Donald Trump speaks during a joint news conference with Australia’s Prime Minister Scott Morrison in the White House in Washington on September 20, 2019. Photo: Jonathan Ernst/Reuters

In the lower house of Parliament, where governments are formed, Labor goes to the voters holding the thinnest of majorities—78 seats in the 151-seat House of Representatives (redistributions will reduce the House to 150 seats at the election). The possibility of Labor being pushed into minority government looms as an equal or even stronger possibility than Labor hanging on to its majority. The Liberal-National Coalition holds 55 seats, while independents and minor parties hold 18. The Coalition will need a net gain of 20 seats from Labor and the cross-benches to return to office. The global electoral trend to punish incumbent government means the Albanese government has lost its lead in the opinion polls. Polls now deliver a near 50-50 split in the two-party vote for Labor and the Coalition; the polling margin of error decides which side is leading in individual polls.

The doyen of the Canberra press gallery, Michelle Grattan, observes that Trump’s victory in the United States will affect the climate of Australia’s campaign: “One obvious point of debate would be how either leader would potentially handle an unpredictable Trump. A Trump presidency might [favor] Opposition Leader Peter Dutton’s national security focus. But an opposite view, held in Labor circles, is it could make people stick to the status quo. Trump’s triumph would also be fodder for the Greens in their attack on Labor’s closeness to the US. For its part, Labor would argue the Australia-US alliance is enduring regardless of individual US and Australian leaders and governments.”

Finishing her term in Canberra, US Ambassador Caroline Kennedy emphasized what will be a key Australian talking point to Trump as she pointed to “the continuity that has characterized this alliance for more than a century.” Kennedy expressed the great alliance story Australia will seek to tell Trump: “Australia may be a middle power, but to the United States, you are number one. We have no more trusted or capable ally. In every dimension of our relationship, I’ve seen the United States rely on Australian leadership and experience. Australia is no longer America’s ‘deputy sheriff’ or whatever the critics like to say. Australia is our partner and often our teacher as the United States navigates a multipolar world. That’s true in our bilateral relationship. It’s true in multilateral fora, and it is vital in this region.”

After phoning Trump to congratulate him the day after the US election, Prime Minister Albanese said they “talked about the importance of the alliance, and the strength of the Australia-US relationship in security, AUKUS, trade and investment. I look forward to working together in the interests of both our countries.”

Albanese told a press conference: “President Trump has run a campaign based on change and he’s made it clear he’s going to do things differently–so we shouldn’t be surprised as things change. But equally, we should be really confident in ourselves and our place in the world as well, and our ability to deliver on our interests together as Australians.”

Albanese denied any need to apologize for previous negative comments on Trump’s first presidency. The most notable example was in 2017, when Albanese was an opposition frontbencher. Asked then how he would deal with Trump, Albanese answered “with trepidation,” going on to say “he scares the s–t out of me and I think it’s of concern the leader of the Free World thinks that you can conduct politics through 140 characters on Twitter overnight.”

Now as prime minister, Albanese says he will work with Trump, adding that he has demonstrated “my ability to work with world leaders and to develop relationships with them which are positive.” Australia’s ambassador in Washington, the former Labor prime minister, Kevin Rudd, acted swiftly after the US election to delete his previous criticisms of Trump. Media turned up plenty of examples of Rudd attacks, calling Trump, “the village idiot” and “the most destructive president in history.” A statement from the Australian embassy announced Rudd’s clean-up:

“In his previous role as the head of an independent US-based think tank [the Asia Society], Mr. Rudd was a regular commentator on American politics. Out of respect for the office of President of the United States, and following the election of President Trump, Ambassador Rudd has now removed these past commentaries from his personal website and social media channels. This has been done to eliminate the possibility of such comments being misconstrued as reflecting his positions as Ambassador and, by extension, the views of the Australian Government. Ambassador Rudd looks forward to working with President Trump and his team to continue strengthening the US-Australia alliance.”

Rudd’s previous criticisms were quoted in an interview with Trump in March by the British politician, Nigel Farage. In response, Trump responded by calling Australia’s ambassador “a little bit nasty,” and “not the brightest bulb.” While saying that the ambassador “won’t be there long,” Trump ended his response to the question about Rudd by noting, “I don’t know much about him.” After Trump’s election, the Albanese government expressed full confidence in Rudd and said he would stay as ambassador. Foreign Minister Penny Wong noted that Trump is “a pretty robust individual” while the alliance “is bigger than any individual or past comments. And in terms of Kevin, Kevin Rudd’s been an excellent Ambassador. He’s delivered an enormous amount for Australia, and I have great confidence that he’ll continue to do so.”

Australia will use the same lines that worked with Trump in his first term. The US has a trade surplus with Australia; or, in Trump-speak, America gets a good deal out of Australia. The balance of trade in America’s favor helped Australia avoid Trump tariffs on Australian steel and aluminum last time round. Australia’s talking points to Trump will highlight the transactional wins the US gets from the relationship. The bilateral free trade treaty with the US, the Australia-United States Free Trade Agreement reaches its 20th birthday in January 2025. The US is Australia’s top foreign investment destination, while the US is Australia’s top foreign investor, as Australia’s Foreign Affairs Department outlines:

“The United States is our largest two-way investment partner, with two-way investment stock reaching A$2.3 trillion in 2023. The United States is by far the largest investor in Australia, with investment stock worth A$1.17 trillion at the end of 2023. The United States is our largest foreign investment destination, with outbound investments reaching A$1.196 trillion in 2023. The United States is our third largest trading partner and two-way trade stood at $98.7 billion in 2023.”

Australia’s tactics for Trump 1.0 will run again for Trump 2.0. When Canberra finds it hard to embrace Trump’s language or agenda, the focus will switch to the greatness of the US, the depth of the bilateral relationship, and the history of military alliance. The alliance narrative during Trump 1.0 was the idea of “100 years of mateship,” dating from 1918 when troops from the two nations fought side by side at the Battle of Hamel on France’s Western Front. Elements of tradition and transaction will be used with Trump 2.0. The alliance tradition will be the long history of mateship, while the transaction will be the promised growth in defense spending to show Australia is no military free rider. The economic pitch will always start from a business bottom line—Australia’s trade deficit means America is in profit.

Canberra’s script will follow the line Foreign Minister Penny Wong used after Trump’s victory: “We have an alliance that’s based on our values, on our history and on our shared strategic objectives. It is a timeless alliance, and we look forward to working with him.”

The US Alliance

“The Biden administration advanced the most consequential and ambitious bilateral security agenda with Australia since World War II.”

US Ambassador to Australia Caroline Kennedy, Nov. 19, 2024

Allowing for normal diplomatic gloss, the ambassador reflects new dimensions in an alliance that is shifting, not merely evolving. Responding to big geopolitical trends, Joe Biden deepened and broadened the alliance and gave it a sharper Australian focus. In its eighth decade, the alliance is coming to Australian soil. The ANZUS history has been Australia joining America’s wars (Vietnam, Afghanistan, Iraq and “the war on terror”). Now the commitment is what America is doing in, with, and for Australia in:

- the AUKUS nuclear submarine agreement;

- the evolution of the Quad grouping of Australia, India, Japan, and the US;

- America’s step-up in the South Pacific, as Washington declared a “renewed partnership with the Pacific Islands,” responding to Australia’s view that China’s challenge creates “a state of permanent contest in the Pacific”;

- the build-up of US military muscle in Australian soil in a new era of alliance integration, with more US troops, planes, and ships in Australia:

- the creation of a US-Australia combined intelligence center in Canberra;

- prepositioning in Australia of US stores, munitions and fuel:

- the lifting of US restriction to reach toward free trade in defense equipment and technology, to achieve more integration of US and Australian industries.

Canberra’s National Defense Strategy, issued in April 2024, said that Australia “must work even more closely with the US, our closest ally and principal strategic partner.” The US is increasing investment in “infrastructure, capability and equipment” on Australian soil, while Australian policy is to strengthen military engagement with the US to:

- focus joint exercises and capability rotations with the US on collective deterrence and force posture cooperation;

- collaborate on defense innovation, science and technology;

- drive interoperability and interchangeability with US systems and capabilities;

- “leverage Australia’s strong partnership with Japan” in the trilateral relationship with the US;

- speed reforms to US “export controls, procurement policy and information sharing to deliver a more integrated industrial base.”

In the words of a Washington Post headline in August, “Australia offers US a vast new military launchpad in China conflict.” On a visit to Darwin, the chairman of the US House of Representatives Foreign Affairs Committee, Michael McCaul, said: “This provides a central base of operations from which to project power.” Building that base means the “biggest expansion of the US military presence in Australia since World War II,” according to James Curran, international editor of the Australian Financial Review and professor of modern history at Sydney University.

Figure 2 Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, U.S. President Joe Biden, and British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak hold a press conference during the AUKUS summit on March 13 in San Diego, California. Photo: Leon Neal/Getty Images

Curran writes that the change in America’s approach since “the mid-1990s has been nothing short of staggering.” After the election of John Howard’s Liberal-National government in 1996, he notes, Canberra offered the Washington training facilities for US marines in northern Australia. The US declined. As the times have changed, so the US has altered its view of the military worth of Australia’s geography. See the official start point for that shift as November 2011, when President Barack Obama announced agreement for an annual marine rotation through Darwin.

The US presence or “posture” in Australia has had bipartisan political support. Noting that political consensus, James Curran questions how the US role in Australia is shifting the alliance foundation from deterrence to offense. “For Australia, the US alliance has always been the critical deterrent – any power considering hostile action towards Australia at least has to keep the existence of the ANZUS treaty in mind,” Curran writes. The central issue for Curran is whether Australia is being transformed “into a base for offensive US operations into Asia. Government language stresses deterrence rather than projection, but the debate is on as to where that line now blurs.”

The elements of the increased US use of Australia’s geography are known as the US Force Posture Initiatives, driven by a bilateral working group formed in 2021. Australia’s Defense Department calls the force posture work “a key component of the alliance” and a “tangible demonstration of the strength of the alliance.” The initiatives involve:

- Enhanced air cooperation “to deepen air-to-air integration that allows for seamless operation” and delivers security and stability across the Indo-Pacific region. Major air bases at Darwin and Tindal (near Katherine) in the Northern Territory are being upgraded. Tindal will be able to house up to six US B-52 bombers. Surveys are being done for upgrades to two air bases in Western Australia and one in northern Queensland. The US pledges to “continue frequent rotations of bombers, fighter aircraft, and maritime patrol and reconnaissance aircraft.”

- Prepositioning: the US is working on the requirements for long-term positioning of Army equipment material in Australia, plus the creation of a logistics support area in Queensland.

- Enhanced land cooperation involves “complex, integrated and combined” exercises and training with allies and partners in the region. The US Army provides capabilities and personnel, fuel infrastructure and explosive ordnance storage.

- During Exercise Talisman Sabre 2025, the US and Australia will test “new operating assumptions” in exercises “across the breadth of Australia.”

- The US supports Australia’s planned infrastructure upgrades at the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, an Australian territory in the Indian Ocean midway between Australia and Sri Lanka.

- Enhanced maritime cooperation to lift the logistics and sustainment capabilities of US surface and subsurface vessels in Australia.

- In Perth, in August, the USS Hawaii, a Virginia-class submarine undertook a maintenance package, the first time that a US nuclear-powered submarine has had maintenance performed outside the US or a US base, or had such work performed by non-US citizens. The Hawaii starts the process of creating a submarine rotational force operating from Western Australia, from the Stirling naval base in Perth. The aim as early as 2027 is to have five conventionally armed, nuclear-powered submarines rotating through Stirling—one sub from the UK and four from the US.

Prime Minister Albanese says work on critical minerals and clean energy has become “a third pillar” to the alliance, to stand alongside security and economic cooperation. The “compact” signed by Albanese and President Biden established climate and clean energy as “a central pillar of the Australia-United States alliance.” The work will deepen collaboration on the “critical minerals and materials that are vital to clean energy as well as defense supply chains.” Australian public opinion about the US is still warm, but trust declines. In the lead-up to the 2024 US presidential election, the annual Lowy Institute poll on how Australians view the world found levels of trust in the United States dropped five points from 2023 to 56%. This continues the fall since 2022, the second year of the Biden presidency, when Australian trust in the US stood at 65%. Using a “feelings thermometer,” Lowy asked Australians about “feelings toward” the US. While still warm, the 2024 measure fell four degrees to 59°, its lowest reading in the 20-year history of the Lowy poll, and down from an all-time high of 73° in 2015.

AUKUS

Australia’s quest for AUKUS nuclear-powered submarines is a thought bubble that turned into a huge project, driven by ambition and beset by anxiety. Canberra’s instant political consensus is a striking element of how quickly the bubble became policy. The Labor-Liberal unity ticket was set at the moment the AUKUS vision was announced by Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States in September 2021.

Figure 3 Navy Sailors assigned to the Los Angeles-class fast-attack submarine USS Annapolis (SSN-760) and HMAS Stirling Port Services crewmembers prepare the submarine to moor alongside Diamantina Pier at Fleet Base West in Rockingham, Western Australia, March 10, 2024. US Navy Photo

The distance covered in three years was emphasized by and Defense Minister Richard Marles when he told Parliament on Aug. 12: “When we came to power, AUKUS was really not much more than a thought bubble, but since then we have been turning it into a reality.” Marles says the thought is sailing along an “actual pathway,” steered by the Australian Submarine Agency, established last year. Some thought! Some bubble! Yet even the believers see an extraordinary journey—the Optimal Pathway, an outline plan for project execution, stretches out to 2053, with the first Australian-built AUKUS submarine due in “the early 2040s.” In August, a naval nuclear propulsion treaty was unveiled, providing the legal basis for AUKUS and the creation of an AUKUS trade zone for exchange of defense goods and technology. The treaty went to the Australian Parliament and US Congress in August and the UK Parliament in September. Marles signed the treaty in Washington on Aug. 5, describing it as “a foundational part of the legal underpinning” of building the nuclear-powered submarine.

The trilateral agreement will operate until 2075. The pact allows the transfer of nuclear propulsion plants to Australia, makes Australia responsible for “management, disposition, storage, and disposal of any spent nuclear fuel and radioactive waste” and gives an Australian indemnity to the US and Britain for any “liability, loss, costs, damage or injury” from nuclear risks. The treaty gives Britain and the US the right to terminate AUKUS and demand the return of nuclear material and equipment. The termination clause can be used if Australia seeks to reprocess nuclear material, builds a nuclear weapon, or breaches its obligations to the Non-Proliferation Treaty and the International Atomic Energy Agency. As part of its nonproliferation pledge, Australia is negotiating a treaty with the IAEA to meet its Article 14 comprehensive safeguards obligations.

In September, the three nations adopted an AUKUS zone for free trade of defense equipment and expertise. The exemptions remove licensing requirements for most controlled goods, technologies, and services. The AUKUS zone will have license-free trade for 70% of defense exports from the US to Australia that are subject to arms traffic regulations, and 80% of defense trade under US export regulations. The deal eliminates the need for 900 export permits covering Australian exports to the US and Britain, valued at $5 billion annually. Taking lessons from the AUKUS effort to cut red tape, the US has also set out principles to build an Indo-Pacific defense industry base.

Richard Marles says a license-free seamless defense industrial base for AUKUS will have “a profound impact,” describing it as one of the biggest reforms to defense trade in decades. In dealing with the new US administration from January, Canberra will push AUKUS as the top policy commitment it wants to reinforce with Trump. After Trump’s victory, Foreign Minister Penny Wong said “obviously we look to particularly prioritising AUKUS in our engagement, which is the thing that we have been most focussed on in the lead up to this election.”

Australia’s Strategy

Summing up foreign policy in a speech on Australia in the world, Albanese said Australia is investing in “deterrence and diplomacy,” transforming defense capability with the AUKUS pact, restoring relations in the South Pacific, revitalizing the Quad, taking a “patient, calibrated and deliberate approach” to China, and supporting the “fundamental guardrail” of US-China dialogue. In a stark view of strategic settings, Albanese and the deputy PM, Richard Marles, declared: “Australia faces the most complex and challenging strategic environment since the Second World War.” The Labor leaders offered that judgement on April 17, 2024, when releasing the National Defense Strategy. The strategy said: “While a major conflict is not inevitable, this new reality is making the pursuit of Australia’s interests more challenging.”

The strategy aims to double defense spending in the next 10 years to lift it from 2% to 2.4% of GDP by 2033-34. The increase in annual funding would see the defense budget grow to more than A$100 billion by 2033-34. The policy document described a strategic environment that continues to deteriorate:

“The optimism at the end of the Cold War has been replaced by the uncertainty and tensions of entrenched and increasing strategic competition between the US and China. This competition is being framed by an intense contest of narratives and values. The competition is playing out in military and non-military ways, including economic and diplomatic. It is accompanied by an unprecedented conventional and non-conventional military build-up in our region, taking place without strategic reassurance or transparency. The effects of this build-up are occurring closer to Australia than previously. This build-up is also increasing the risk of military escalation or miscalculation that could lead to a major conflict in the region.”

The Albanese government has scrapped the old “balanced force” model for the Australian Defense Force (ADF). The balanced force demanded lots of capabilities to keep options open. The balanced force could be adjusted to respond to whatever needs, contingencies, or dangers appeared on the horizon. An unbalanced future has arrived, and the balanced force is judged unfit for purpose. The ADF must become “an integrated, focused force” to face what Defense identifies as strategic risks that “have continued to deteriorate.” The new guidance to Defense from government is capitalized as “a Strategy of Denial,” calling for an ADF that can:

- defend Australia and our immediate region;

- deter through denial any adversary’s attempt to project power against Australia through our northern approaches;

- protect Australia’s economic connection to our region and the world;

- contribute with our partners to the collective security of the Indo-Pacific region;

- contribute to the maintenance of the global rules-based order.

A Strategy of Denial is appropriate for a nation that’s been through the stages of grieving for the disintegration of the liberal international order (denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance).

Canberra proclaims it will take a “more focused approach to its international engagement.” The “focused” thinking can mean Australia is less willing to look beyond its region. Thus, in December, 2023, Canberra rejected Washington’s request to send an Australian Navy ship to the Red Sea as part of international efforts to safeguard cargo from attacks by Iranian-backed Houthi rebels. Richard Marles said Australia would not contribute a ship or plane to the Combined Maritime Forces that patrol the shipping route: “We need to be really clear around our strategic focus, and our strategic focus is our region—the northeast Indian Ocean, the South China Sea, the East China Sea, the Pacific.” The disappointed response from a US official was that Australia could not “pretend global problems don’t require global solutions.”

Australian responds to US-China competition as “a primary feature of our security environment,” a struggle over the global balance which will be “sharpest and most consequential in the Indo-Pacific.” The National Defense Strategy describes China’s expanding gray-zone activities and “coercive tactics” in its forceful handling of territorial disputes and unsafe intercepts of vessels and aircraft operating in international waters and airspace. China is improving its capabilities in all areas of warfare at a “pace and scale not seen in the world for nearly a century,” with no transparency about its strategic purpose, prompting this Canberra judgement: “The risk of a crisis or conflict in the Taiwan Strait is increasing, as well as at other flashpoints, including disputes in the South and East China Seas and on the border with India. There is increasing competition for access and influence across the Indian Ocean, including efforts to secure dominance over sea lanes and strategic ports. That said, US-China dialogue, both at the leader-level and military-level, is useful in preventing miscalculation and ensuring differences can be worked through in a way that supports stability.”

China: Seeking Balance as Economic Coercion Cools

“China does not see itself as a status quo power. It seeks a region and a world that is much more accommodating of its ambitions and its interests.”

Prime Minister Albanese, Dec. 20, 2023

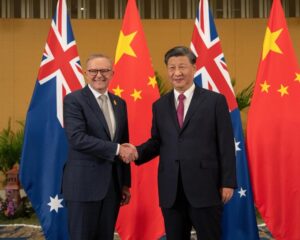

“Over the past decade, we have made some progress in China-Australia relations and also witnessed some twists and turns. That trajectory has many inspirations to offer. Now, our relations have realised a turnaround and continues to grow, bringing tangible benefits to our two peoples.”

President Xi Jinping, Nov. 18, 2024.

Australia’s understanding of China’s future strategic pressure is shaped by Beijing’s recent unsuccessful, but costly, economic coercion. China’s trade sanctions on Australia have been wound back. Beijing’s refusal to talk to Australian leaders has ended. A relatively conventional diplomatic rhythm has resumed. Labor came to office in 2022 saying it would “stabilize” dealings with China, and stability has been achieved. China has scrapped its tariffs and unofficial customs bans on coal, barley, beef, wine, timber, lobsters, and cotton. Australia’s Trade Minister, Don Farrell, says nearly A$20 billion worth of “trade impediments on Australian exports to China have been removed.”

While defrosting with Beijing, the Albanese government kept getting warmer with Washington. The symbolic expression of this was in the prime minister’s back-to-back visits to the US and China. First, Albanese went to Washington at the end of October 2023. Then, a week later, he was in Beijing, the first visit by an Australian leader in seven years.

In Washington, Biden and Albanese proclaimed a new era of strategic cooperation to build what Albanese calls “an alliance for the future.”

As Australian journalists and TV crews gathered in the Oval office to record the grip-and-grin between Biden and Albanese, the president offered the Australians some unprompted remarks about the dragon in the room. “I was asked by Xi Jinping a couple of years ago why I was working so hard with your country,” Biden noted. “I said. ‘we’re a Pacific nation.’ He looked at me and I said, ‘Yeah, we’re a Pacific nation, the United States, and we’re going to stay that way’.”

Figure 4 Anthony Albanese meets Xi Jinping in Beijing. Photo: Australian Strategic Policy Institute

China welcomed Albanese in November 2023, seeking to cement the reset in relations, blaming past troubles on Australia’s previous Liberal-National government. The official China Daily described the trip as “ice-breaking” after dialogue halted in 2016 “because of the previous Australian government’s adversarial stance toward China.” Part of the thaw has been an end to China’s ban on Australian journalists. In August, 2024, Will Glasgow, a correspondent for Rupert Murdoch’s paper, The Australian, returned to China, almost exactly four years since Australian correspondents fled the country. Glasgow wrote: “The beginning of the return of Australian media is another manifestation of the improvement in diplomatic relations with China under the Albanese government, which continues despite a host of ongoing disagreements…It is by no means an exclusively Australian problem. The size of the English-language foreign-media presence here is a fraction of what it was when I was based in Beijing for The Australian in the first half of 2020.”

One of the continuing disagreements is China’s suspended death sentence on the Australian citizen, Dr Yang Jun. The sentence was denounced by Foreign Minister Wong in February, saying Australia was “appalled” at the “harrowing news” The “many years of uncertainty” since Yang’s detention on national security charges in 2019 were “extraordinarily difficult,” Wong said, and Australia would protest “in the strongest terms.” In November, Wong attacked the sentencing of Australian citizen Gordon Ng in Hong Kong “for organising and participating in an election primary.” Wong said Australia is gravely concerned at China’s broad application of the national security law and its use against Australian citizens

In Australia, public sentiment toward China remains low. The Lowy Institute survey of Australian attitudes to the world found only 17% of Australians say they trust China “somewhat” or “a great deal” to act responsibly in the world (only Russia ranks lower in Australian opinion). This is steady from 2023 and a minor increase on 2022, when trust in China reached a record low (12%). The low numbers are a contrast with the figure just six years ago, when half (52%) of Australians trusted China. The suspicion of China reflects the icy years of trade coercion, and publicity about Chinese cyber-attacks on Australia.

Australia’s chief spy-catcher, Mike Burgess, acknowledges that all nations spy, but charges that China’s “behavior goes well beyond traditional espionage.” The director-general of security says: “The Chinese government is engaged in the most sustained, scaled and sophisticated theft of intellectual property and expertise in history. It is unprecedented and it is unacceptable. China has developed a ruthless business model to seize commercial advantage. Stealing intellectual property is the first step. Then they use talent programs, joint ventures and acquisitions to harvest the expertise required to exploit the intellectual property. Sometimes the technology is put to military use, often it’s given to favoured companies to mass produce it, under-cutting and undermining the innovator.”

Australia in Comparative Connections: 2009-2024

The first annual account of Australia’s connections with the US and East Asia appeared in this series in 2009. Thus, this year’s report is the 16th in the series I have written. My initial chat with the doyen of Pacific Forum, Ralph Cossa, set the scene for the warmest partnership any journalist could ask for. How long should my annual piece be? “Whatever it needs,” replied Ralph. Subject range, I asked? “Over to you,” responded Ralph. And so it has gone, ever since. Apart from Americanizing my spelling, the words have all be mine. Would that all editors were so generous of spirit, liberal about length, and open on content.

Looking back, that first 2009 effort offered two big themes that have endured. One pole was the continuity and comfort of the alliance fundamentals between Australia and the US. The other pole was the “tectonic effects being exerted by China’s rise. As with the rest of the Asia-Pacific, Australia is adjusting significant aspects of its foreign and security policy to the magnetic pull of China.” Official Australian usage is now “Indo-Pacific” not “Asia-Pacific.” But much else has endured, as one other line from that first effort observed: “For the first time in Australia’s history, its most important market is not also an alliance partner. Instead, it will be its major ally’s strategic competitor, perhaps even challenger.”

The 2011 report observed that Australia had decoupled from the US economy in ways unimaginable in the 20th century. In the first decade of the 21st century Australia did not follow the US into recession in 2001 and 2008. Asia’s business cycle now drives Australia’s economy: “Australia’s alliance commitment with the US no longer mirrors, as it once did, the economic ties to the US.” This annual series traced the 12-nation negotiations for the Trans-Pacific Partnership, launched in 2008, as the talks (and arm wrestling and haggling) crawled toward an ever-shifting finish line. In the arcane world of trade negotiators, the battle between the US and Japan was trench warfare lit by pyrotechnics. As Barack Obama observed, the TPP was an ambitious US effort to write the future trade rules of the Asia-Pacific, reflecting American interests in areas such as intellectual property rights, and labor and environmental standards.

The TPP was signed but then Australia watched in horror as the 2016 US presidential campaign trashed the agreement.” In the Australian interpretation,” I wrote in 2016, “a US that turns away from the TPP would also be turning away from Asia.” In his first week in office in 2017, Trump signed an executive order formally withdrawing the US from the TPP. Yet Washington commentary noted this was mere formality, because the treaty was already dead in Congress. My 2017 comment: “Can you create an enhanced trade structure to buttress the US strategic role in the Asia-Pacific if the US opts out of that trade pact?” A US turning protectionist is going to stress test the link between security and trade.

To end this round up of commentary/judgements, turn to the professionals in the game—the ambassadors (one Australian and two Americans) and an academic.

When an Australian jumps out of a New York taxi and prepares to make a dash across 5th Avenue, the habit of a lifetime is to look the wrong way for the traffic. Australia drives on the left; America drives on the right. It’s a simple metaphor for the many ways of looking and moving of the two nations. Rushing for a late-night drink in the city that never sleeps, Australia’s ambassador to the US, Joe Hockey (2016-2020), stopped his taxi by Central Park and dashed across the avenue, checking in the Australian direction. That “near-fatal error,” Hockey observed in his memoir, was “like so many who think they understand America.”

In 2010, the US and Australia marked the 70th anniversary of their formal diplomatic relationship. US Ambassador to Canberra, Jeffrey Bleich (2009-2013) said the relationship existed long before the 1940 treaty and extended far beyond words on paper: “Before there were diplomats in each other’s capitals, there were world-travelling whalers and miners, sailors of the Great White Fleet and their gracious Australian hosts, yanks and diggers hunkered down in trenches in World War I. We’ve trusted each other… We’ve valued each other’s freedom, self-reliance, open markets and sense of fair play. We’ve taken our work seriously, without taking ourselves too seriously. And when we’ve disagreed, we’ve done it without being disagreeable.”

During the 2013 Australian election, the American intellectual Francis Fukuyama visited and judged that the bitterness of Australian politics has not reached the intensity of the US: “Australia has got the fewest big long-term problems of any developed democracy I know. In policy terms, the fight within Labor, or even between Labor and the Liberals seem minor when compared to the things that [polarize] Americans, such as the legitimacy of taxation, dealing with the deficit, abortion and guns.”

Wrapping up her time in Canberra, the 27th US ambassador to Australia, Caroline Kennedy, used a farewell at the National Press Club in November to sketch what Australia means to her: “I will miss the Australian sense of humor and the fact that everyone has a nickname. I will miss the way Australians are up for anything and pitch in to help each other out. I will miss the amazing creatures here, from the magpies and whale sharks to my two new embassy sheep, Louie and Eli. I can’t wait to come back and visit. There is so much left to see and do. Most of all, I know the best days for our alliance are yet to come.”

Oct. 11, 2023: After three years detention in China, Australian citizen Cheng Lei returns to Australia. The Australian government has been seeking the journalist’s release since she was detained in August 2020.

Oct. 14, 2023: In a national referendum, Australia’s voters reject a constitutional amendment to recognize Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as the nation’s first people and create a Voice to Parliament advisory body.

Oct. 20, 2023: A federal government review of a Chinese company’s 99-year lease on the Port of Darwin finds “robust” regulations and “monitoring mechanisms” mean it is “not necessary to vary or cancel” the 2015 sale.

Oct. 24, 2023: PM Albanese opens the new Australian Embassy in Washington.

Oct. 25, 2023: After White House talks, President Biden and PM Albanese proclaim a new era of US-Australia strategic cooperation.

Oct. 27, 2023: Unable to address the US Congress because of the House of Representatives’ wrangle over a new speaker, PM Albanese instead delivers an address at the US State Department on “An alliance for the future.”

Nov. 7, 2023: In Beijing, PM Albanese meets China’s president, Xi Jinping.

Nov. 9, 2023: Pacific Islands Forum leaders meeting held in Cook Islands.

Nov. 10, 2023: PM Albanese and Prime Minister of Tuvalu Kausea Natano announce a “union” of Australia and Tuvalu. Requested by Tuvalu, the union creates a “special pathway” for its citizens to settle in Australia. Canberra’s security guarantee means it will have oversight of any partnership or engagement Tuvalu has with other states on security and defense.

Nov. 14, 2023: In international waters inside Japan’s Exclusive Economic Zone, HMAS Toowoomba stops so divers can clear fishing nets entangled around propellers. A Chinese destroyer in the vicinity generates sonar pulses, causing “minor injuries” to the Australian divers. Australia expresses serious concerns to the Chinese government about this “unsafe and unprofessional misconduct.”

Nov. 17, 2023: APEC summit held in San Francisco. PM Albanese says APEC’s “focus on practical action is pivotal in supporting an open trade and investment environment.”

Nov. 20, 2023: Second India–Australia 2+2 Ministerial Dialogue, between foreign and defense ministers, is held in New Delhi.

Nov. 25, 2023: Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defense Richard Marles signs a Strategic Partnership with President of the Philippines Ferdinand R Marcos Jr.

Dec. 2, 2023: US Secretary of Defense, Lloyd J Austin, hosts Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defense Marles and UK Secretary of State for Defense, Grant Shapps, at the Defense Innovation Unit Headquarters in California, to discuss AUKUS.

Dec. 4, 2023: Annual South Pacific Defense Ministers’ meeting convenes in New Caledonia.

Dec. 7, 2023: In Canberra, PM Albanese and Prime Minister of Papua New Guinea James Marape, announce a Bilateral Security Agreement covering defense, policing, border and maritime security, and nontraditional areas of cyber security, climate change, gender-based violence and critical infrastructure.

Dec. 19, 2023: In a foreign policy speech on Australia in the world, PM Albanese said Australia is investing in “deterrence and diplomacy,” transforming defense capability with the AUKUS pact, restoring relations in the South Pacific, revitalizing the Quad, taking a “patient, calibrated and deliberate approach to China, and supporting the “fundamental guardrail” of US-China dialogue.

Jan. 12, 2024: Australia joins Bahrain, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Netherlands, New Zealand, Republic of Korea, UK, and the US in a statement on the Red Sea, condemning “illegal, dangerous, and destabilising Houthi attacks against vessels.”

Jan. 15, 2024: To “support international diplomatic efforts toward a durable peace in the Middle East,” FM Penny Wong leaves to visit Jordan, Israel, the Occupied Palestinian Territories, and United Arab Emirates.

Feb. 1, 2024: Inaugural Australia-New Zealand ministerial consultations on foreign affairs and defense held in Melbourne.

Feb. 5, 2024: Australian citizen Dr. Yang Jun receives a suspended death sentence in Beijing. FM Wong says Australia is “appalled” at the “harrowing news.” China has held Yang since January 2019 on national security charge. Wong said Australia will communicate its response “in the strongest terms.”

Feb. 8, 2024: Papua New Guinea PM James Marape becomes the first South Pacific leader to address the Australian Parliament. Marape and PM Albanese held the fifth Papua New Guinea-Australia Annual Leaders’ Dialogue pointing to the “cultural, historical and geographical” bonds between the two countries.

Feb. 14, 2024: Australian House of Representatives passes a motion, urging the US and the UK to end their prosecution of Australian citizen Julian Assange, founder of Wikileaks.

Feb. 15, 2024: PM Albanese issues a joint statement with the prime ministers of Canada and New Zealand expressing “grave concerns” at Israel’s plan to begin an offensive into Rafah, saying the military operation would be “catastrophic.”

Feb. 20, 2024: The federal government releases its blueprint to double the combat fleet of the Australian Navy, planning for 26 major surface ships and 25 minor war vessels.

Feb. 29, 2024: Philippines President Ferdinand Marcos Jr addresses Australian Parliament, vowing not to yield an “inch” to China and praising the strategic partnership with Australia as “more important than ever.”

Mar. 19, 2024: Prompted by a British interviewer, former President Donald Trump attacks Australia’s ambassador to Washington, Kevin Rudd, calling him “nasty” and claims Rudd will not last as Australia’s ambassador. FM Wong responds that Rudd is doing an “excellent job” and will remain ambassador if Trump wins the presidential election in November.

Mar. 20, 2024: China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi has talks in Canberra with FM Wong in the seventh Australia-China Foreign and Strategic Dialogue. The trip makes Wang the most senior Chinese government visitor to Australia since 2017.

Mar. 28, 2024: China’s Ministry of Commerce announces the end of tariffs on Australian wine, a punitive measure that had wiped out an export trade worth A$1.2 billion. The wine tariff is one of the last elements of China’s campaign of economic coercion against Australia.

Mar. 30, 2024: US Marines arrive in the Northern Territory for an eight-month rotation, the 13th rotation of Marines to Darwin.

Apr. 5, 2024: United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres appoints former Australian Foreign Minister Julie Bishop (2013-18) as his Special Envoy on Myanmar.

Apr. 7, 2024: Australia, Japan, the Philippines, and US conduct “Maritime Cooperative Activity” in the Philippine Exclusive Economic Zone, involving naval/maritime and air force units, “in recognition of rights in international law and UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.”

Apr. 9, 2024: AUKUS partners, Australia, the US, and United Kingdom, announce they are “considering cooperation with Japan” on AUKUS Pillar II advanced capability projects.

Apr. 9, 2024: PM Albanese announces that the Vice Chief of the Australian Defense Force, V. Adm. David Johnston, will take over as the new Chief of the Defense Force.

Apr. 10, 2024: In Washington, President Biden and Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio announce work on a trilateral “networked air defense architecture” with Australia. The joint statement flags cooperation with Japan on “AUKUS Pillar II advanced capability projects.”

Apr. 17, 2024: Deputy PM and Defense Minister Marles launches the National Defense Strategy and Integrated Investment Program, doubling defense spending in the next 10 years from 2% to 2.4% of GDP by 2033-34.

Apr. 22, 2024: PM Anthony Albanese travels to Papua New Guinea to meet Prime Minister Marape to spend two days walking the Kokoda Track used during WW2 and commemorate Anzac Day.

Apr. 27, 2024: Deputy PM and Defense Minister Marles visits Ukraine to express support and announce extra military help.

May 1. 2024: The defense and foreign ministers of Australia and South Korea meet in Melbourne to advance the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership.

May 4, 2024, In Hawaii, defense ministers of Australia, Japan, the Philippines, and US agree to step-up military drills with the Philippines. Australia’s Richard Marles refers to the West Philippine Sea, snubbing China’s usage of the South China Sea.

May 4, 2024: A PLA Airforce fighter aircraft intercepts Australian Defense Force helicopter and releases flares across its flight path. The Australian helicopter was embarked on HMAS Hobart, which was contributing to UNSC sanctions enforcement against North Korea.

May 14, 2024: Annual federal budget is presented to Parliament.

Jun. 4, 2024: Australian Defense Force will open recruitment for non-Australian citizens. Permanent Australian residents from Canada, New Zealand, the UK and US will be able to enlist in the ADF.

Jun. 26, 2024: Wikileaks founder Julian Assange returns to Australia after walking free from a US court in Northern Mariana Islands, under a plea deal, ending a 14-year fight against extradition and US espionage charges.

July 1, 2024: Sam Mostyn is sworn in as the 28th governor-general of Australia, the second female to serve as the representative of Australia’s Head of State.

July 7, 2024: Deputy Prime Minister and Defense Minister Marles leaves for the US to attend the NATO summit and the Australian-American Leadership Dialogue.

July 11, 2024:Russian-born Australian army private and her Russian-born husband are arrested on espionage charges after allegedly working to steal sensitive defense information for Russia.

Aug. 5, 2024: Australia raises official terrorism threat level to “probable,” defined as a greater than 50% chance of an attack in the next 12 months. The announcement reverses the November 2022 decision to lower the alert level to “possible.”

Aug. 7, 2024: Annual AUSMIN talks held in Annapolis, involving Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin with Australia’s FM Wong and Deputy Prime Minister and DM Richard Marles.

Aug. 12, 2024: Australian government tables in Parliament a further AUKUS agreement with the UK and the US, enabling the transfer of material and equipment for Australia’s future nuclear-powered submarines.

Aug. 19, 2024: Indonesia’s President-elect Prabowo Subianto visits Canberra to announce that the Australia-Indonesia Defense Cooperation Arrangement will be upgraded to a treaty level agreement.

Aug. 21, 2024: Australia gives environmental approval for the “largest solar precinct in the world” — a $19 billion project to transport electricity from Darwin to Singapore via a 2,670-mile submarine cable.

Aug. 30, 2024: The 53 Pacific Islands summit held in Tonga. Leaders endorse Australia’s Pacific Policing Initiative.

Sept. 21, 2024: Leaders of Australia, India, Japan, and the US meet in Delaware for the Quad summit.

Sept. 22, 2024: FM Penny Wong leads Australia’s delegation to the 79th session of the United Nations General Assembly.

Sept. 26, 2024: Defense ministers of Australia, the UK, and US meet in London to discuss AUKUS.

Oct. 3, 2024: South Pacific Defense Ministers’ Meeting is held in New Zealand.

Oct. 10, 2024: PM Albanese visits Laos for East Asia Summit and the ASEAN-Australia Summit.

Oct. 17, 2024: Australia gives 49 Abrams tanks to Ukraine, bringing the total value of Australia’s military assistance to Ukraine to A$1.3 billion.

Oct. 22, 2024: Australia will spend A$7 billion to buy long-range missiles from the US.

Oct. 24, 2024: PM Albanese attends the Commonwealth Heads of Government summit in Samoa.

Nov. 5, 2024: The 15th Australia-India Foreign Ministers’ Framework Dialogue is held in Canberra.

Nov. 12, 2024: Inaugural Australia-Philippines Defense Ministers’ Meeting is held in Canberra.

Nov. 17, 2024: 14th Trilateral Defense Ministers’ Meeting is held in Darwin, involving Australian DM Marles, Japanese Defense Minister Nakatani Gen, and US Secretary of Defense Austin.

Nov. 18, 2024: Third bilateral summit between PM Albanese and China’s leader Xi Jinping, held on the sidelines of the G20 meeting in Brazil. The meeting marks the 10th anniversary of the comprehensive strategic partnership between the two nations

Nov. 19, 2024: PM Albanese attends the G20 summit in Brazil.