Authors

Andy Lim

Andy Lim is an Associate Fellow with the Korea Chair at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), where he manages the internship program, social media, events, and supports research for Dr. Victor Cha. He is also responsible for several grant projects, including the U.S.-Korea NextGen Scholars Program, and the ROK-U.S. Strategic Forum. His research interests are the U.S.-ROK alliance, Northeast Asia and North Korea. His work on Chinese predatory liberalism has appeared in The Washington Quarterly (with Victor Cha) and on North Korea has appeared in Foreign Policy (with Victor Cha). He earned a B.A., cum laude with honors in international studies from American University’s School of International Service.

Articles by Andy Lim

Japan - Korea

May — December 2024Trump 2.0, South Korea’s Martial Law, and Future of Seoul-Tokyo Relations

The year 2025 marks the 60th anniversary of the normalization of diplomatic relations between Seoul and Tokyo. It was originally expected to be a milestone year for bilateral ties and a fitting culmination of nearly three years of hard work by two leaders: President Yoon Suk Yeol and former Prime Minister Kishida Fumio. But that outlook now seems hung in the balance, with new unknowns on the horizon—both expected and unexpected. In this final issue on Japan-Korea relations, we discuss the key factors that are likely to impact the future of bilateral ties and the Camp David trilateral in four major areas: 1) Trump 2.0, 2) political uncertainty in Seoul, 3) weak political support in Tokyo, and 4) resurfacing history issues. The final months of 2024 have brought new unknowns in the shape of leadership changes in the United States, Japan, and potentially South Korea. It is now possible that come January 2025, the leadership trio—President Biden, Prime Minister Kishida, and President Yoon that has made the Korea-Japan rapprochement and the unprecedented trilateral partnership possible will be gone from office.

What happens next is impossible to predict, but one hopes that the hard-fought and laboriously planned institutionalization of bilateral and trilateral ties will withstand these changes in leadership. This will be the first true test for Seoul-Tokyo-Washington trilateral partnership since the Camp David summit in August 2023.

Japan’s new prime minister, Ishiba Shigeru, and President Yoon agreed in mid-November to “further elevate the bilateral relationship to new heights” towards 2025 and to promote comprehensive cooperation in areas such as “politics, security, economy, culture and social security.” However, following President Yoon’s declaration of martial law on Dec. 3, the future of Seoul-Tokyo relations faces a great deal of uncertainty. Given that it was President Yoon’s political will that initially facilitated rapproachment, depending on what happens to his political future and who comes into office in South Korea, Seoul-Tokyo relations may experience challenges. While conflicts over long-standing history issues have been consciously minimized during this period of rapproachment, they have not gone away, as demonstrated by their inability to reach a consensus on a joint event on the controversial Sado mine.

Trump 2.0 and US alliances with Seoul and Tokyo

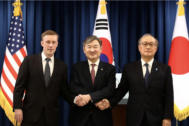

Figure 1 President Yoon Suk Yeol shakes hands with Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba during a bilateral meeting at a hotel in Vientiane, Laos, Thursday. Photo: Yonhap

When thinking about the future of Japan-Korea relations, the most important events in 2024 revolve around (potential) changes in leadership—one expected (the US), one mostly unexpected (Japan), and one possible yet totally unexpected (South Korea). The 2024 US presidential election and the re-election of Donald Trump has re-introduced uncertainty into the region, casting a shadow of anxiety not only over bilateral Japan-Korea relations but also the future of trilateral cooperation. Foreign policy did not play a big role in this election. But candidates presented starkly different visions regarding US priorities and values. These differences would ultimately influence the fate of the liberal international order, within which the Camp David trilateral cooperation drives its significance.

Despite the unexpected withdrawal of President Biden from re-election, Kamala Harris’ candidacy was largely seen as a continuation of his administration’s key policies—the institutionalization of trilateral US-Korea-Japan relations and the strengthening of Washington’s traditional alliances with Japan and South Korea. In contrast, no one truly knows what the former President Trump will do. If history is any guide, hiss approach is likely to make these relations more transactional, with less focus on common values.

At the end of the Cold War, a major debate emerged within the US over whether to continue stationing American forces in Asia. Some questioned why the US should bear the cost of defending wealthy Asian countries. Ultimately, the US maintained its presence, guided by the famous rationale put forward by Joseph Nye, then assistant secretary of defense for international security affairs, who argued that “security is like oxygen—you tend not to notice it until you begin to lose it, but once that occurs, there is nothing else you will think about.” Fundamentally, Trump does not share this perspective on security. Instead, he views it as just another business transaction.

For both Tokyo and Seoul, there is growing concern about being in Trump’s crosshairs, as they may fail to meet two of his sacrosanct priorities—defense spending and trade balance. In the words of one expert, both countries are in the “danger zone” because they have large trade surpluses with the US, and spend less than 3% of their GDP on defense. This belief has been consistent with Trump’s worldview since the 1990s, with a clear message that it does not matter whether you are an ally or an adversary, it’s America first. There are concerns he will ask for the allies to pay more. Furthermore, according to another expert privy to conversations with Japanese officials in Tokyo, the new Trump team might even add two more conditions: how many US Treasury securities they have purchased and whether they manipulate their currency.

If Trump’s first term is any clues about his second, US alliances with Seoul and Tokyo are likely to experience the “fear of abandonment”—the anxiety that Washington might not be a reliable ally for their national security. Strong deterrence against North Korea is a key area that has repeatedly united Seoul, Tokyo, and Washington. But this may not be taken for granted under a Trump 2.0 administration. In the near term, trilateral multidomain military exercises like the newly-introduced Freedom Edge may be curtailed or stopped because it is expensive.

A remote but plausible development under a Trump 2.0 administration is an intensified discussion of US troop withdrawals from South Korea. In an interview with a South Korean news outlet Yonhap, Elbridge Colby, former deputy assistant secretary of defense for strategy and force development during Trump’s first term—who is being discussed as a potential defense secretary—said, “South Korea is going to have to take primary, essentially overwhelming responsibility for its own self-defense against North Korea because we don’t have a military that can fight North Korea and then be ready to fight China.” He further noted, “The fundamental fact is that North Korea is not a primary threat to the US. It would not be rational to lose multiple American cities to just deal with North Korea.”

If Washington under Trump 2.0 sends a signal reflecting this stance, this could possibly push South Korea to search for alternative security arrangements. Such alternatives may ultimately result in less optimal outcomes from the perspective of the US-South Korea alliance. Another issue is more political. Trump said little about North Korea during his campaign. But if he chooses to directly engage with Kim Jong Un, while sidelining South Korea, this is not a good signal from the perspective of alliance management.

Therefore, Trump’s victory on Nov. 5 immediately created some consternation in both Seoul and Tokyo, with both sides scrambling to find ways to reach the re-elected president’s orbit and to brush up on their personal charm. Planning for the return of Trump to the White House has been at the top of every world leader’s mind since the election. Without the effective Trump whisperer Abe Shinzo, Japan might find it harder the second time around. But Prime Minister Ishiba may find a way to connect with Trump enough to make sure Japanese equities for the next four years are protected. And over in South Korea, President Yoon Suk Yeol reportedly restarted practicing golf in an attempt to connect personally with Trump, an avid golfer.

Martial Law and Political Uncertainty in South Korea

Figure 2 South Korean soldiers outside the National Assembly in Seoul in the early hours of Wednesday. Images Photo: Chung Sung-Jun/Getty

The most unexpected development is the inexplicable and short-lived martial law on Dec. 3 in South Korea. In and outside the country, people are genuinely baffled as to why President Yoon suddenly declared martial law, as there was no apparent reason that the public can understand as a basis for such a drastic move. Martial law, introduced in 1948, was last imposed in 1979 before South Korea’s democratization. For many South Koreans, martial law is a reminder of the country’s authoritarian past, thus prompting many to ask “Are we back to the 1970s before democratization?” Having achieved democratization through years of grassroots struggle, the move caused strong negative reactions against the backdrop of immense pride that South Koreans have for their democracy. Prior to Yoon’s declaration of maritial law, criticism of his leadership has been mounting within South Korea, largely driven by scandals. Now, impeachment discussions have intensified. Calls for his resignation have grown louder. His political future is highly uncertain.

Yoon’s action, which was purely aimed at a domestic issue—the opposition—has created consequences that reverberates far beyond the peninsula, at a time when the regional threat from China, North Korea, and Russia continues to grow. The reverberating effects of that event have left Seoul incapacitated at a critical time not just in domestic politics but in regional relations, with new governments in both Washington and Tokyo. While the quick overturning of the martial law is a resounding victory for democracy and the democratic process, the policy and leadership paralysis as Korea figures out a way forward can lead to “Korea passing” as other regional actors move ahead on critical issues in the new year.

With the political uncertainty in Seoul, all this leads to the pressing question of who will shepherd this very important but prickly bilateral relationship moving forward. The recent improvement in Seoul-Tokyo relations was largely the work of President Yoon, which also laid the groundwork for the Camp David trilateral cooperation. Without him in the picture, the future of Japan-Korea relations becomes highly uncertain. In a hypothetical scenario where South Korea’s main opposition leader, Lee Jae-myung, assumes office, the rapprochement between Seoul and Tokyo would likely come to an end. Lee and his supporters would be expected to prioritize demands for Japan to address unresolved historical issues, potentially undoing recent progress in bilateral relations.

In particular, beneath the public debate over the constitutionality, rationale, and implications of the short-lived martial law declaration, there was one paragraph that caught our and others’ attention in the conclusion of the first impeachment motion submitted by the six South Korean opposition parties on Dec. 4. The paragraph read as follows:

“In addition, under the guise of so-called “value diplomacy,” Yoon has neglected geopolitical balance, antagonizing North Korea, China, and Russia, adhering to a bizarre Japan-centered foreign policy, and appointing pro-Japan individuals to key government positions, thereby causing isolation in Northeast Asia and triggering a crisis of war, abandoning his duty to protect national security and the people.”

The line “bizarre Japan-centered” foreign policy and references to “pro-Japan individuals” clearly illustrates what the opposition party thinks about Yoon’s policy to improve relations with Tokyo. This has been a long-standing criticism of Yoon’s foreign policy, for being too pro-Japan, overly dependent on the US, and too anti-China and anti-North Korea. We have pointed out before that Yoon’s “low-reward unpopular decision” to reconcile with Japan required a lot of political capital, but it is still very stark to see a disagreement over foreign policy be included in a lengthy impeachment bill focused primarily on domestic issues.

While this paragraph is no longer present in the second impeachment motion, it gave us a preview into what an opposition-run South Korean presidency might do in terms of foreign policy. If the current front-runner and Democratic Party leader Lee Jae-myung wins, we might see a reversal in key positions on China, Japan, North Korea, and the US.

Based on his previous public statements, we cannot discount the possibility of an abrogation of the budding US-Korea-Japan trilateral (which might have happened anyway under Trump 2.0), a bypassing of Japan, and a more balanced and even conciliatory approach to China and North Korea. Lee has in the past called a trilateral military alliance “unnecessary” because its exacerbates instability on the peninsula and forces North Korea-China-Russia to align more closely, and have argued forcefully for a more “pragmatic” approach in US-China competition. Lee could possibly come into office in 2025 with a very different geopolitical environment than Yoon’s in 2022, with a revived North Korea-China-Russia axis, a de facto military alliance between its two neighbors in North Korea and Russia, and a retrenched United States.

All of this does not bode well for Japan and South Korea, especially with the speed at which the returning US president might shake things up at the start of his second term. People who are worried about the first 100 days of the Trump presidency might now need to buckle up for the first 100 hours as there are now expectations that the changes coming out of the White House will be breakneck and immediate. For South Korea, unfortunately, there might not be a leader definitively in charge on Jan. 21 to be able to respond to Trump’s actions, or to make that all-important personal connection with him.

As of this writing, President Yoon have vowed to “fight to the end” for a chance to make his case in court during an impeachment hearing. Under this timeline, the impeachment process can take up to six months to resolve in court (to remove or reinstate him), and then a two-month period before a presidential election can be held. We are potentially looking at a dire situation where Korea might be politically unstable and leaderless until August 2025. That’s a long time in any political calendar, and for Seoul, even if it successfully defends its democracy, it might re-emerge much weaker regionally and internationally as the rest of the world moves on.

Ishiba and Weak Political Support in Japan

Figure 3 Shigeru Ishiba, the newly elected leader of Japan’s ruling party, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) poses in the party leader’s office after the LDP leadership election Photo: REUTERS/Kim Kyung-Hoon/Pool

Another change is the decision by Kishida Fumio to resign in mid-August ahead of the LDP party election in September. The result was not a total surprise, given a series of domestic setbacks for him this year: political fundraising scandal, electoral defeats and consistently poor approval ratings (below 30%). After nearly three years as Prime Minister, Kishida is leaving behind a clear foreign and security policy legacy—increasing defense spending to nearly 2%, reorienting efforts to improve Japan’s security environment, delivering strong support for Ukraine, and most importantly, pushing for rapprochement with Korea. This legacy was apropos of someone who served as Japan’s longest serving foreign minister in the postwar period. As we have discussed often, leaders dictate policy, and it takes two leaders to tango. Kishida’s support for improving prickly Japan-Korea relations—coupled with like-mindedness from Yoon—made Camp David and rapprochement possible. While regional relations lost a stalwart champion in Kishida this fall, his replacement—the longtime LDP politician and former defense minister Ishiba—is likely to follow a similar well-trodden path in foreign policy.

Ishiba Shigeru, a man who famously ran for LDP leadership four times before succeeding on the fifth try, came into office in October 2024 after winning a closely-contested leadership contest with a well-documented track record as a defense hawk and some interesting ideas for North Korea and regional relations. While early talks of an “Asian version of NATO” and nuclear sharing has subsided after initial pushback—his idea of working with Pyongyang directly might gain some traction if President Trump resumes his bromance with Kim Jong Un. His plan to establish liaison offices in both capitals, while not novel, has seen some opposition from families of abductees. For the time being however, the liaison office idea has also been placed on the backburner, as he reaffirmed during a November 2024 national rally on the abduction issue the standard Japanese policy of normalizing relations with North Korea by first resolving the outstanding abduction, nuclear and missile issues. During that speech, he also reiterated his openness to a summit with the North Korean leader and even implored Kim Jong Un “not to miss this opportunity.”

Before the political debacle in South Korea, Ishiba had already signaled his intention to continue the shuttle diplomacy of his predecessor and to press ahead with efforts to further improve bilateral relations. Ishiba and Yoon have already met twice, once on the sidelines of the ASEAN summit in Laos, and again on the sidelines of the APEC Summit in Peru—plus holding the first and last trilateral in the current leader configuration. During their October and November meetings, the two leaders had agreed to “further elevate” the bilateral relations in preparation for the important 2025 anniversary. In late November, there were rumblings of a potential January 2025 visit to Seoul by Ishiba. This early visit would have kickstarted an important year for the bilateral relations, the 60th anniversary of normalization. There were already speculations earlier this year that the two leaders—then Kishida and Yoon—might make a “future-oriented” joint statement to commemorate the occasion. Furthermore, there were additional plans for senior Japanese officials to visit Korea in December, including a bipartisan group of lawmakers from the Korea-Japan Parliamentary Federation in mid-December to be led by former Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide, and an end of the year visit by Japanese Defense Minister Nakatani Gen, which would have been the first visit in nine years.

But all those plans were unceremoniously shelved after the shocking situation in Seoul, with Prime Minister Ishiba saying he is watching the developments with “particular and grave” concern. US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin similarly cancelled a planned stop in Korea—part of his last Asia trip with stops in both Tokyo and Seoul to reassure and commit to trilateralism before a Trump transition. Other trilateral efforts planned for December were also casualties of this “unforeseen circumstance,” including a session of the Nuclear Consultative Group (plus a related exercise) and a trilateral forum on women’s economic empowerment. With Ishiba’s January visit called off at the time of this writing, there are increasingly growing concerns that shuttle diplomacy between the two neighbors will become difficult for the time being until the domestic situation in Seoul is resolved. While it is too early to rule out any breakthroughs for 2025, what is certain now is that the political turmoil in Seoul has thrown off course a carefully calibrated transition and shifted tailwinds into headwinds for the foreseeable future.

Resurfacing History Issues

A kerfuffle over the commemoration of the controversial Sado mine in November revealed the limits of foreign policy objectives over deep rooted historical grievances. The two sides were unable to reach a consensus on a joint event, and instead held two separate events. Moreover, ritual offerings by Japanese leaders to the controversial Yasukuni Shrine remains a perennial problem, though the decision by Ishiba to send an offering, instead of visiting in person in October revealed that he will likely be more cautious in this aspect, unlike what some more conversative members of his party such as Takaichi Sanae—who visited in person—might want from him. Experts have pointed out that other historical problems, including the potential depletion of third-party reimbursement for forced labor victims might resurface in the coming year. As we pointed out last year, a binational survey showed that there remain three major problems for a true “future-oriented” relations, all of which revolved around the question of history: resolving historical disputes; addressing Dokdo/Takeshima; and improving historical perceptions and education.

Figure 4 President Yoon Suk Yeol hold hands with Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba, fourth from right, and Chinese Premier Li Qiang, second from right, during the 27th ASEAN Plus Three Summit held at the National Convention Center in Vientiane, Laos, Thursday. From left are Thai Prime Minister Srettha Thavisin, Vietnamese Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh, President Yoon, Ishiba, Laotian Prime Minister Sonexay Siphandone, Li and Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim. Photo: Yonhap

And finally, Prime Minister Ishiba will meander into the new year with weak political support, losing a majority in the October parliamentary election, and surviving a rare November run-off. The results meant that for the time being, Ishiba will need to focus inwardly on fixing the Japanese economy and addressing voters’ concerns over political scandals. He will not have the wherewithal to focus outwardly anyway because without a parliamentary majority, it would have been difficult to pass some of his bolder foreign policies. The situation in Korea also makes it much harder for any positive developments on either side, setting up an unfortunate lost opportunity in an anniversary year in 2025.

Japan - Korea

January — April 2024Business As Planned Amid Domestic Challenges

Following major turning points and breakthroughs of 2023, the start of 2024 has been steady, coordinated, and ordinary. In contrast to the highs and lows of the past five years, the rhythm of the relationship between Korea and Japan has settled to a welcome tone of “business as usual,” and business as planned. Both Prime Minister Kishida Fumio and President Yoon Suk Yeol faced serious challenges to their leadership with record low approval ratings and the conservative People Power Party’s defeat in Korea’s parliamentary elections. But for now, Japan-Korea relations are thriving as they follow through on commitments made at the Camp David summit. Washington, Seoul, and Tokyo continued to tick off their laundry list of promised deliverables from that summit. While they might no longer be meeting at the breathtaking pace of a trilateral meeting every 3.5 days, the three partners continued to meet almost bi-weekly at all levels, including the Cabinet level.

Japan - Korea

September — December 2023The Year 2023—Major Turning Point and Blossoming Cooperation

The year 2023 was a turning point for Japan-South Korea relations. There was a breakthrough in the issue of compensating forced laborers, which led South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol and Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio to meet seven times since their summit in March. Shuttle diplomacy has been fully resumed. By year’s end, their cooperation in new areas such as energy, critical and emerging technology, development and humanitarian assistance, space, and cyber is blossoming. Last year will be remembered as the year that began to demonstrate a real potential for Seoul and Tokyo to be like-minded global partners, along with Washington. If the first half of 2023 was a speed chase to get to the finish line—the Camp David trilateral summit meeting—the latter half of 2023 was a coordinated plan to prepare for many more races. As noted in our last issue of Comparative Connections, the Camp David trilateral summit represented a potential harbinger for the future of Japan-Korea relations.

Japan - Korea

May — August 2023Camp David: Institutionalizing Cooperation Trilaterally

Japan-South Korea relations are going strong. In the months leading up to the historic Camp David trilateral summit in August, we saw the return of shuttle diplomacy between Korea and Japan. If President Yoon Suk Yeol’s March visit to Japan was groundbreaking, Prime Minister Kishida Fumio’s May visit to Seoul signified the continued momentum of improving bilateral ties. The Aug. 18 trilateral summit meeting, where President Biden, President Yoon, and Prime Minister Kishida announced bold steps to cement trilateral cooperation into the institutional fabric of the relationship, represents the deepest attempt in recent memory. A successful trilateral summit like this one was possible only because Seoul and Tokyo mended their bilateral ties. A positive cycle is expected the other way around, as well. For example, the “Commitment to Consult” —to expeditiously “share information, align messaging and coordinate response actions” among the three leaders—will likely create more incentives and opportunities for Seoul and Tokyo to keep bilateral relations friendly and cooperative.

Japan - Korea

January — April 2023The Return of Shuttle Diplomacy

In March 2023, Japan and South Korea had a long-awaited breakthrough in their bilateral relations, which many viewed as being at the lowest point since the 1965 normalization. On March 16, South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol and Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio held a summit in Tokyo and agreed to resume “shuttle diplomacy,” a crucial mechanism of bilateral cooperation that had been halted for about a decade. Behind the positive developments was President Yoon’s political decision on the issue of compensating wartime forced laborers. The two leaders took steps to bring ties back to the level that existed prior to actions in 2018 and 2019, which precipitated the downward spiral in their relationship. Japan decided to lift the export controls it placed on its neighbor following the South Korean Supreme Court ruling on forced labor in 2018. South Korea withdrew its complaint with the World Trade Organization on Japan’s export controls. Less than a week after the summit, Seoul officially fully restored the information sharing agreement (GSOMIA) that it had with Tokyo. They also resumed high-level bilateral foreign and security dialogues to discuss ways to navigate the changing international environment together as partners.

Japan - Korea

September — December 2022Japan and South Korea as Like-Minded Partners in the Indo-Pacific

The last four months of 2022 saw a flurry of bilateral diplomatic activities between Japan and South Korea in both nations’ capitals and around the world. They focused on 1) North Korea, 2) the issue of wartime forced labor, and 3) the future of Seoul-Tokyo cooperation in the Indo-Pacific region. Despite mutual mistrust and the low approval ratings of Prime Minister Kishida Fumio and President Yoon Suk Yeol, both leaders had the political will to see a breakthrough in bilateral relations. Another signal came in the form of new strategy documents in which Seoul and Tokyo explained their foreign and security policy directions and goals. On Dec. 16, the Kishida government published three national security-related documents—the National Security Strategy (NSS), the National Defense Strategy (NDS), and the Defense Buildup program. On Dec. 28, the Yoon government unveiled South Korea’s Strategy for a Free, Peaceful, Prosperous Indo-Pacific Region, its first-ever Indo-Pacific strategy. Although each document serves a somewhat different purpose, it is now possible to gauge how similarly or differently Japan and South Korea assess challenges in the international security environment, and how they plan to respond to them.

Japan - Korea

May — August 2022The Passing of Abe and Japan-Korea Relations

How might the passing of former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo impact Tokyo’s approach to Seoul? This unexpected turn of events loomed large in the minds of many who have been cautiously optimistic that Japan and South Korea would take steps toward a breakthrough in their stalled relations. In our last issue, we discussed how this summer could provide good timing for Seoul and Tokyo to create momentum in this direction after Yoon Suk Yeol’s inauguration as president in South Korea and the Upper House election in Japan. However, the results from this summer were mixed. Seoul and Tokyo have not yet announced whether Yoon and Kishida will hold a summit any time soon. Both leaders ended the summer juggling domestic politics amid declining approval ratings. However, there were some meaningful exchanges between the two governments, signaling that both sides were interested in improving relations.

Japan - Korea

January — April 2022South Korea’s New President and a Seoul-Tokyo Reset?

What impact will the victory of Yoon Seok-yul in South Korea’s presidential elections have on Seoul-Tokyo relations? During his campaign, Yoon repeatedly emphasized the “strategic importance of normalizing” and improving relations with Japan. It was an open secret that Yoon was Tokyo’s preferred candidate. With his May inauguration, opportunities for a diplomatic reset are on the horizon. Unsurprisingly, however, Japan is responding cautiously to overtures. Prime Minister Kishida Fumio sent his foreign minister to Yoon’s inauguration on May 10, instead of attending himself, especially as he looks to the Upper House election in July. Seoul and Tokyo will probably schedule a long-awaited summit meeting when they begin to move toward addressing the issue of wartime forced laborers. That issue has strained bilateral ties since the South Korean Supreme Court ruled in favor of Korean wartime forced laborers in separate decisions in late 2018, leading to drawn-out legal processes against the court orders. Yoon’s election win has not changed the Japanese position, which maintains that the reparations issue was fully settled by the 1965 normalization treaty.

Japan - Korea

September — December 2021Awaiting a Breakthrough? PM Kishida and South Korea’s Presidential Candidates

The year 2021 ended with no breakthroughs in Japan-Korea relations. Bilateral ties remain stalled over South Korea’s 2018 Supreme Court ruling on forced labor during Japan’s occupation of the Korean Peninsula and Japan’s export restrictions placed in 2019 on key materials used for South Korea’s electronics industry. The inauguration of Kishida Fumio as Japan’s new prime minister in September did not lead to a new momentum for addressing these bilateral issues, as both Tokyo and Seoul adhered to their positions. Prime Minister Kishida, while acknowledging that Japan’s relationship with South Korea should not be left as is, largely reiterated Tokyo’s official stance from the Abe and Suga governments that Seoul should first take steps on the forced labor issue. South Korean President Moon Jae-in sent a letter congratulating Kishida on his inauguration, signaling willingness to talk about bilateral challenges. Developments in the final months of 2021 are a reminder that there is no easy solution to these issues in sight.