Articles

What impact will the victory of Yoon Seok-yul in South Korea’s presidential elections have on Seoul-Tokyo relations? During his campaign, Yoon repeatedly emphasized the “strategic importance of normalizing” and improving relations with Japan. It was an open secret that Yoon was Tokyo’s preferred candidate. With his May inauguration, opportunities for a diplomatic reset are on the horizon. Unsurprisingly, however, Japan is responding cautiously to overtures. Prime Minister Kishida Fumio sent his foreign minister to Yoon’s inauguration on May 10, instead of attending himself, especially as he looks to the Upper House election in July. Seoul and Tokyo will probably schedule a long-awaited summit meeting when they begin to move toward addressing the issue of wartime forced laborers. That issue has strained bilateral ties since the South Korean Supreme Court ruled in favor of Korean wartime forced laborers in separate decisions in late 2018, leading to drawn-out legal processes against the court orders. Yoon’s election win has not changed the Japanese position, which maintains that the reparations issue was fully settled by the 1965 normalization treaty.

South Korea’s Foreign Policy Changes and Japan

At stake in South Korea’s March 9 presidential election was Seoul’s role in the shaping of international order, an impact more far-reaching than any other election. The two rival candidates—Lee Jae-myung of the incumbent progressive Democratic Party and Yoon Seok-yul of the main opposition conservative People Power Party—presented competing visions of South Korea’s foreign policy, with promises to take the country in a different direction in terms of its place in regional and global affairs. President-elect Yoon speaks of the need for South Korea to take a more proactive role in global diplomacy and “to firmly demonstrate [its] attitude of respect for the international rules-based order.” The outcome of this election will likely bring the foreign policies of South Korea and Japan into closer alignment than during the Moon Jae-in presidency.

South Korea’s policy toward North Korea will go through significant changes under Yoon. Compared to Lee, who shares the assumption with Moon that dialogue and other positive incentives can lead Pyongyang to denuclearize, Yoon believes Pyongyang should first take steps toward denuclearization before any positive incentives, such as the lifting of sanctions, are offered. Japan’s North Korea policy, under Kishida and his predecessors Suga Yoshihide and Abe Shinzo, has primarily rested on pressure and sanctions over dialogue, even while Tokyo was open to a summit with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un for resolution of the abduction issue.

The alliance with the United States is another area where we might see more coordination and alignment of views between Seoul and Tokyo. During the campaign, the foreign policy platforms of the two candidates in large part represented conservative and progressive camps, with Yoon pledging to restore and strengthen the alliance with the US. Yoon’s victory means that governments in both Japan and South Korea will place a strong alliance with the US at the center of their foreign policies.

Figure 1 South Korean Foreign Minister Chung Eui Yong, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken, and Japanese Foreign Minister Hayashi Yoshimasa meet in Honolulu on February 12, 2022. Photo: Japanese Foreign Ministry

This also promises stronger trilateral US-Korea-Japan security cooperation over North Korea, which will in turn work favorably for Seoul-Tokyo relations. Trilateral coordination on North Korea has been robust under the Biden administration. Following a record number of missile tests by North Korea, top nuclear envoys of the US, South Korea, and Japan met in Hawaii on Feb. 10 to discuss ways to restart dialogue with North Korea. Coordination continued when the top diplomats of each country met in Hawaii two days later to discuss North Korean provocations, how to hold them accountable, and ways to restart negotiations. South Korean Foreign Minister Chung Eui-yong also had his first face-to-face meeting with Japanese counterpart Hayashi Yoshimasa, who took office in October 2021.

US and Japanese policymakers will pay a great deal of attention to how South Korea’s new government will navigate its relationship with China. South Korea’s China policy under Yoon may move away from the Moon government’s position of avoiding decisions on regional issues that appear to take sides between Washington and Beijing. It is still unclear whether the change in South Korea’s approach to Beijing will be nuanced or bold, and what such a change might mean for South Korea’s relations with Japan. Still, Yoon’s desire to play a more proactive role in shaping the contours of international order is likely to facilitate tighter cooperation among the three countries in nontraditional security areas such as energy, technology, and communication. US President Joe Biden’s scheduled visit to South Korea and Japan in late May will further strengthen the effort.

Yoon’s Search for Breakthrough and Japan’s Response

President-elect Yoon has called for a mutually beneficial, “future-oriented” relations in the mold of a Kim-Obuchi 2.0 era in writing, in interviews, and in meetings with the Japanese. The signal has been unequivocal. He even promised in his first interview as president-elect that bilateral relations “will go well.” Yoon believes the previous administration exploited bilateral relations for domestic political gain, causing relations to hit rock bottom. He has vowed to separate diplomatic and economic issues from domestic politics, and to seek comprehensive solutions to disputes over history, trade, and security.

This optimism is buoyed by Yoon’s desire to look to the future, and by Kishida’s promise of a “realist diplomacy for a new era.” The day after Yoon’s victory, the two leaders spoke on the phone and agreed that they should meet to mend ties. After the call, Kishida told reporters that “Japan and South Korea are important neighbors and healthy bilateral ties are essential in protecting the rules-based international order and in ensuring peace, stability, and prosperity in the region and the world.” Kishida was the second leader to speak with Yoon, after President Biden.

In late April, Yoon sent a delegation to Japan for policy consultations. The delegation, led by five-term lawmaker and National Assembly Vice Speaker Chung Jin-suk, is the second special delegation sent by Yoon, following a group that visited Washington the first week of April. Prior to the trip, Chung told Korean media that the new administration wants “future-oriented” relations with Japan and emphasized that “Yoon’s thought is that restoring ties between South Korea and Japan, which have been left unattended at one of their worst points, serves our national interests.”

During the first day of meetings on April 25, the delegation met Japanese Foreign Minister Hayashi and Trade Minister Hagiuda Koichi, where they discussed bilateral issues and export controls. On April 26, the delegation met and delivered a letter from Yoon to Kishida. During their 25-minute meeting, Prime Minister Kishida said “there is no time to waste in improving Japan-South Korea relations,” and that “strategic cooperation between Japan and South Korea, and among Japan, the US, and South Korea, is more necessary than ever.” In a press conference after the meeting, Kishida said “fulfilling promises made to each other is a basic rule between nations,” referencing recent disputes over wartime forced labor and women forced into sexual slavery by the Japanese military (“comfort women”). Chung, head of the Korean delegation, told reporters after the meeting that they agreed to work together for “shared interests,” and that Kishida shared Yoon’s desire for a forward-looking relationship while facing up to shared history, in the spirit of the Japan-South Korea Joint Declaration of 1998 between Prime Minister Obuchi Keizo and President Kim Dae-jung.

Prior to the South Korean delegation’s visit, it was unclear whether a meeting with Kishida would take place. According to a Japanese media outlet, Kishida made the decision to meet the delegation only after hearing the report of Foreign Minister Hayashi’s exchanges with the delegation the day before. Some within his Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) questioned whether it would be helpful for Kishida to meet with the delegation without a tangible sign that Seoul is taking steps to resolve the forced labor issue. Kishida recently singled out this issue as a “major sticking point” in the relationship. Ultimately, he met the delegation and reiterated Japan’s position on the issue.

Figure 2 A delegation of foreign policy aides to South Korean President-elect Yoon Suk-yeol meets Prime Minister Kishida Fumio in Tokyo on April 26, 2022. Photo: Kyodo

Both Kishida and Yoon agree that bilateral relations cannot remain as is and need repairing as soon as possible. However, the challenges ahead are not small for either man. Within the LDP, there is a skeptical view that predicts that South Korea will change its position again and that Japan may lose face if it agrees to take steps to improve relations with Seoul now. Japanese public opinion is also pessimistic. According to a Kyodo News survey in late March, 72.2% of Japanese respondents remain skeptical about major changes in Japan’s relations with South Korea, answering that Seoul-Tokyo relations will not change under Yoon despite his willingness to improve relations. Only 18.9% said that bilateral relations will improve. The same survey showed that 42.1% said that they would cast proportional representation votes for the ruling LDP this summer.

Kishida will likely wait until after the July Upper House election to meet Yoon, instead of sending his foreign minister to his inauguration. A hypothetical scenario where Kishida’s in-person attendance at Yoon’s inauguration is followed by South Korea’s scheduled liquidation of Japanese companies’ assets would pose a political risk for him in the Upper House ballot. However, it is worth noting that within Japan, there are those who argue that Kishida should use the inauguration ceremony as an opportunity to reset relations with South Korea. In an editorial, Japan’s left-leaning Asahi pressed Kishida to attend the inauguration to break a deadlock.

Despite Yoon’s willingness to push for future-oriented relations with Japan, his government will have to work with political leaders in the soon-to-be opposition Democratic Party who do not share Yoon’s views of Japan. The issue of wartime forced labor compensation will remain thorny in South Korea. According to the progressive South Korean daily Hankyoreh, Yoon’s advisors are reviewing several options, including former National Assembly Speaker Moon Hee-sang’s proposal that companies from both Japan and South Korea donate funds to compensate the plaintiffs. But any proposal that deals with this issue will require the Yoon government to work with the Democratic Party, which retains a majority in the National Assembly. In early January, news came out that the South Korean Supreme Court had on Dec. 27 dismissed a second appeal by Japan’s Mitsubishi Heavy Industries against a court order to sell two patents to compensate a victim of forced labor. The first appeal was dismissed by the Supreme Court in September 2021. There is another pending case in a lower court in Daejeon.

North Korea

For now, it is perhaps on policy coordination over North Korea that Japan and South Korea’s willingness to cooperate will be most visible. North Korea began 2022 with a bang, ringing in the new year with seven different missile tests in January, the most ever in a month. The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February created a favorable environment for North Korea to continue its testing campaign, as Russia and China are unlikely to support additional sanctions at the UN Security Council. As of April 30, it has conducted 13 different tests and demonstrated troubling technological advances. It broke a four-year self-imposed moratorium on ICBM tests on March 24, and said it tested new types of hypersonic missiles, a long-range cruise missile, tactical guided weapon, and an ICBM, all part of Kim Jong Un’s plan to modernize his military capabilities.

In early April, Japan responded to the North’s ICBM test by expanding and extending unilateral sanctions. While the outgoing Moon government has condemned the North’s provocations, it has not expanded sanctions in hopes of salvaging inter-Korean talks. The Yoon administration is expected to take a tougher stance toward the North, and to align more closely with the US and Japan.

Figure 3 An apparent new type of solid fuel missile rolls through Kim Il Sung Square on Monday, April 25, during a military parade in Pyongyang, North Korea on April 26, 2022. Photo: KCTV via NK News

North Korea held a military parade on April 26 to celebrate the 90th anniversary of the Korean People’s Army (KPA), and displayed new military capabilities, including a possible new solid fuel submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM). Speaking at the parade, Kim Jong Un vowed to speed up development of nuclear forces at the “fastest possible speed.” Furthermore, his ambiguous message of an “unexpected secondary mission” for his nuclear forces if “any forces try to violate the fundamental interest of our state” has led many to conclude that he has updated North Korea’s nuclear doctrine to be more aggressive—but there is no official North Korean nuclear doctrine.

The Yoon transition team responded to the parade by stressing the urgent task for South Korea to build the capability needed to deter the North’s nuclear and missile threats, including the completion of the three-axis system, which includes: 1) Korea Massive Punishment and Retaliation (KMPR), targeting North Korean leadership in case of a conflict, 2) the Kill Chain pre-emptive strike platform—which would target the North’s nuclear and missile facilities—and 3) the Korea Air and Missile Defense system (KAMD).

Japan’s proposed revision on April 26 to its security and diplomatic policies, including the National Security Strategy, is a reminder of the growing regional threats to Japan’s security. The proposal specifically mentioned new hypersonic weapons being deployed by China and North Korea as impetus for Japan to acquire new counterattack capabilities for stronger deterrence.

As North Korea continues to systematically improve its military capabilities, expect both South Korea and Japan to continue bolstering their own capabilities. While the Yoon transition team drew the line at holding combined US-Korea-Japan military exercises for now, there are incentives for stronger security cooperation.

Korea-Japan Trade

Expectations are high in both capitals for economic relations to improve under the two new leaders. A late-April 2022 survey of 327 Korean companies by the Korea Chamber of Commerce and Industry (KCCI) showed optimism for improved bilateral relations, with 45.3% of respondents believing in improved relations, while 44% expect no change. This is in stark contrast to a similar survey taken just six months ago by KCCI, in which only 12.9% of companies expected improved relations, while 80% expected the status quo to remain. There are many opportunities for the two governments to work together bilaterally and multilaterally, including but not limited to multilateral agreements such as the CPTPP and the Quad, digital trade, supply chain resiliency, economic security, among others.

The first quarter of 2022 saw positive developments in two major multilateral free trade agreements in the Indo-Pacific. The first was the 15-member Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the world’s largest FTA (accounting for 30% of the world’s GDP) which officially took effect for South Korea in February 2022, making this the first FTA with both South Korea and Japan as members.

The second was South Korea’s official decision on April 15 to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). South Korea will soon submit an official application, and the Yoon administration will work on the negotiations, which is expected to take at least one year. So far, seven of the 11 CPTPP members have expressed support for South Korea’s membership, while Chile, Japan, Peru, and Singapore have yet to publicly express a position. South Korea convened a meeting of ambassadors from 10 CPTPP members on April 28, all except for Japan, and they expressed support. South Korea needs unanimous support from all 11 members for accession. According to government estimates, accession will increase Korea’s real GDP by 0.33 to 0.35%, and boost trade and investment. If South Korea joins the CPTPP, it will be the second FTA involving both Korea and Japan.

South Korea’s ban on seafood imports from eight Japanese prefectures near Fukushima, in force since 2013 over radiation level concerns, is likely to remain. The South Korean trade ministry has made clear that this is a health and safety issue, and said that lifting the ban is not a precondition for CPTPP membership, a position reinforced by the Oceans and Fisheries Ministry.

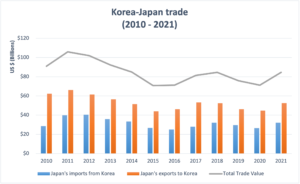

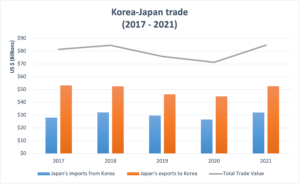

This brings us to the overall health of the bilateral economic relationship. The 2019 trade dispute between Korea and Japan over export controls brought about a series of tit-for-tat actions that led to a highly publicized deterioration of relations. In reality, the economic impact has been minimal. A recent study (a co-author is from the Bank of Korea) quantifying the overall economic impact found only a small “welfare loss of 0.144% ($1.0 billion) for Korea and 0.013% ($346 million) for Japan,” with minimal sectoral impacts, including a 0.25% decrease in the production of chemical goods in Japan. For reference, South Korea’s and Japan’s GDP in 2020 were $1.64 trillion and $5.05 trillion, respectively. Furthermore, the graph below shows minimal change in overall bilateral trade under the Moon administration, with 2021 numbers even surpassing 2017, the year Moon took office.

Figure 4 Korea-Japan trade between 2010-2021. Source: UN Comtrade database

Figure 5 Korea-Japan trade between 2017-2021. Source: UN Comtrade database

Lingering Bilateral Issues

While there is optimism in both capitals for better “future-oriented” relations under Yoon and Kishida, especially over North Korea and economic relations, many lingering historical and territorial disputes remain.

A new historical dispute emerged in late January 2022, when Japan decided to nominate the mine on Sado Island for the 2023 UNESCO World Heritage list. This was controversial because the mine is associated with Korean wartime forced labor, with as many as 2,000 Koreans forced to work there during World War II. The Korean foreign ministry and the Blue House strongly protested the decision and immediately launched a task force to thwart the bid. The issue will resurface during the Yoon administration as UNESCO is expected to visit the Sado mine this fall before deciding next May—a two-thirds majority of the 21 World Heritage Committee members is needed—whether to add the Sado mine to the list.

Conflict over different representations of history and claims of territory simmered again in late March when the Japanese government completed its screening of high school textbooks to be used next year, which included removal of terms such as “wartime,” “forced arrest,” and “forced conscription” when describing forced labor victims and comfort women. The textbooks will also again write that Dokdo/Takeshima is an “inherent part” of Japanese territory. The South Korean foreign ministry protested by saying this distorts historical facts because the removal of terms dilutes the “coercive nature” of those acts and criticized Japan’s “preposterous claims” over the disputed islet. Japanese Chief Cabinet Secretary Matsuno Hirokazu responded by saying the Korean protest was “unacceptable” because those revisions are in line with the government’s consistent stance on the issues.

Once Yoon comes to office, the thorny issue of comfort women is another reality that his government will have to address. President Moon has questioned the legitimacy of the 2015 agreement, believing it to be a flawed deal that excluded the victims and the public. His government dissolved the foundation created by the agreement. In the past year, South Korean courts have ruled for and against “comfort women” in separate rulings in January and April 2021. There have also been mixed rulings by South Korean courts on whether Japanese government assets can be seized to pay legal costs, including two rulings in June 2021 with opposite conclusions, one for and one against. It remains to be seen how President-elect Yoon will handle this delicate but important issue. One early indication came from Foreign Minister-nominee Park Jin, who has publicly acknowledged that the 2015 comfort women deal is an official one and that Korea and Japan will work together to “recover the honor and dignity of the victims.”

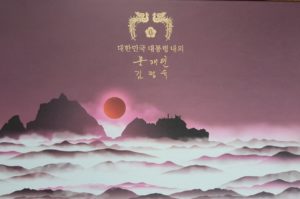

Figure 6 The image on the box of South Korean President Moon Jae-in’s gift sent to foreign ambassadors in the country to mark the Lunar New Year. The gift was refused by the Japanese Embassy in Seoul, which claimed that the box bore an image of the contested Dokdo/Takeshima islets. Photo: Yonhap

On the issue of the disputed Dokdo/Takeshima, barring a deliberate action like the December 2021 police chief’s visit, or a diplomatic faux paus like the Lunar New Year gift in January 2022, the issue should not surface again this year. A Japanese day commemorating the islet—Takeshima Day—occurred in February, and Japan’s annual diplomatic bluebook protesting Korea’s “illegal occupation” was published in late April.

There also remain concerns in Korea and other neighboring countries over Japan’s plan to release more than 1 million tons of contaminated wastewater from the Fukushima Daiichi power plant into the Pacific Ocean. Prime Minister Kishida has stated the planned disposal of wastewater—to start in Spring 2023 over the next four decades—should not be delayed when he visited the plant last October. A UN task force visited the plant in February 2022 to collect water samples and they are expected to release their findings at the end of April.

Looking to the Future

The timing of a Kishida-Yoon summit meeting will depend in large part on domestic politics in Japan and South Korea, which leads us to believe that it will be after the Upper House election in July. The key highlights of this summer will include President Biden’s visit to Seoul and Tokyo in May, his first Asia trip, as well as the NATO summit in June, where the two leaders might attend. Barring a major eruption of disputes over history that changes the public mood, South Korea will likely reach out to Japan to begin a reset of relations. As cautious as the Kishida government is, the Biden administration’s desire to see strained Seoul-Tokyo relations mended will be no small factor in Tokyo’s deliberation to recalibrate its policy on South Korea. Kishida now has a willing partner in Yoon to work with, and many issues to cooperate on, including the one neighbor that routinely threatens both with missiles.

Jan. 11, 2022: Supreme Court of South Korea dismisses second appeal filed by Japan’s Mitsubishi Heavy Industries against the forced sale of two of its patents to compensate forced labor victims.

Jan. 13, 2022: South Korea’s Deputy Defense Minister Kim Man-ki, US Assistant Secretary of Defense for Indo-Pacific Security Affairs Ely Ratner, and Japan’s Director General for Defense Policy Masuda Kazuo hold phone talks to discuss North Korea’s recent missile tests and reaffirm trilateral cooperation.

Jan. 17, 2022: South Korea’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs protests Japanese Foreign Minister Hayashi Yoshimasa’s remarks reiterating Japan’s claim to the disputed islet of Dokdo/Takeshima during a parliamentary speech.

Jan. 17, 2022: US Special Envoy for North Korea Sung Kim, South Korea’s Special Representative for Korean Peninsula Peace and Security Affairs Noh Kyu-duk, and Director-General of the Japanese Foreign Ministry’s Asian and Oceanian Affairs Bureau Funakoshi Takehiro hold phone talks to discuss North Korea’s missile launch.

Jan. 22, 2022: Japanese embassy in Seoul sends back the Lunar New Year gift box from South Korea’s presidential office Cheong Wa Dae, claiming the box contains an illustration that resembles the disputed islet of Dokdo/Takeshima.

Jan. 28, 2022: Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio announces plans to nominate the mine on Sado Island for the 2023 UNESCO World Heritage designation. South Korea protests because of the mine’s ties to Korean forced labor during World War II, which may have included as many as 2,000 laborers.

Jan. 30, 2022: South Korea’s Special Representative for Korean Peninsula Peace and Security Affairs Noh Kyu-duk and Director-General of the Japanese Foreign Ministry’s Asian and Oceanian Affairs Bureau Funakoshi Takehiro hold bilateral phone talk to discuss North Korea’s launch of an intermediate-range ballistic missile the same day.

Feb. 1, 2022: RCEP (the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership) takes effect for South Korea. This 15-member free trade agreement is the first to have both South Kore and Japan as members.

Feb. 1, 2022: Japan’s Cabinet approves plan to submit the nomination of the mine on Sado Island to the UNESCO World Heritage list. Japan submits a letter of recommendation to the UNESCO World Heritage Center the same day.

Feb. 2, 2022: US Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman, South Korea’s First Vice Foreign Minister Choi Jong-kun, and Japan’s Vice Foreign Minister Mori Takeo hold trilateral phone call to discuss North Korea’s missile launches and denuclearization efforts.

Feb. 3, 2022: South Korea’s presidential office Cheong Wa Dae vows to respond to Japan’s nomination of the Sado mine in a “systematic and omnidirectional manner.” South Korean Foreign Minister Chung Eui-yong lodges a protest during a phone call with Japanese foreign minister Hayashi, voicing his “deep disappointment” over Japan’s nomination.

Feb. 4, 2022: South Korea launches a government-private task force to respond to Japan’s nomination of the Sado mine to the UNESCO World Heritage list.

Feb. 4, 2022: South Korea’s Deputy Defense Minister Kim Man-ki, US Assistant Secretary of Defense for Indo-Pacific Security Affairs Ratner, and Japan’s Director General for Defense Policy Masuda Kazuo hold phone talks to discuss North Korea’s missile threat, reaffirm trilateral cooperation and reiterates plans to hold a trilateral defense ministerial in the future.

Feb. 10, 2022: US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin, South Korean Defense Minister Suh Wook, and Japanese Defense Minister Nobuo Kishi hold trilateral phone talk to discuss the North Korean missile threat and trilateral cooperation.

Feb. 10, 2022: US Special Envoy for North Korea Sung Kim, South Korea’s Special Representative for Korean Peninsula Peace and Security Affairs Noh Kyu-duk, and Director-General of the Japanese Foreign Ministry’s Asian and Oceanian Affairs Bureau Funakoshi Takehiro meet in Hawaii to discuss ways to restart dialogue with North Korea.

Feb. 12, 2022: South Korean Foreign Minister Chung Eui-yong and Japanese Foreign Minister Hayashi hold bilateral talks in Hawaii to discuss North Korea, shared history, and other bilateral issues. This is Hayashi’s first in-person bilateral meeting with Chung since he took office in October 2021. Chung, Hayashi and US Secretary of State Antony Blinken meet for a trilateral meeting the same day, and call for North Korea to stop provocations and return to dialogue.

Feb. 22, 2022: Director-general for Asia and Pacific affairs at the South Korean Ministry of Foreign Affairs Lee Sang-ryeol calls in the deputy chief of mission of the Japanese embassy in Seoul Naoki Kumagai to protest “Takeshima Day,” an annual event about the dispute islet that is attended by Japanese officials.

Feb. 23, 2022: South Korean FM Chung meets UNESCO Director-General Audrey Azoulay in Paris and expresses concerns over Japan’s nomination of the Sado mine to the UNESCO World Heritage list.

Feb. 23, 2022: Seoul Central District Court dismisses damage lawsuits filed by two former Korean wartime force laborers against Japan’s Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Ltd. and Kumagai Gumi Co. Each sought 100 million won ($83,800) in compensation. The court did not explain its ruling, but many believe it to be over the expiration of the statute of limitations, like previous rulings.

March 1, 2022: South Korean President Moon Jae-in calls on Japan to “squarely face history” and “take leadership as an advanced nation” during a speech commemorating the March 1st Independence Movement.

March 1, 2022: South Korea opens the National Memorial of the Korean Provisional Government, a new museum in Seoul dedicated to the history of the Korean Provisional Government.

March 10, 2022: Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio congratulates South Korean president-elect Yoon Seok-yul for his victory in the presidential election, saying that “healthy bilateral relations are indispensable.”

March 11, 2022: Prime Minister Kishida and President-elect Yoon speak on the phone for the first time since Yoon’s victory. They agreed on the importance of improving ties and resolving pending issues. Kishida is the second leader to speak with Yoon, after President Joe Biden.

March 14, 2022: US Special Envoy for North Korea Sung Kim, South Korea’s Special Representative for Korean Peninsula Peace and Security Affairs Noh Kyu-duk and Director-General of the Japanese Foreign Ministry’s Asian and Oceanian Affairs Bureau Funakoshi Takehiro hold trilateral phone talk to discuss recent North Korean provocations, including tests of an ICBM system.

March 15, 2022: Busan City Government releases a plan to prepare for Japan’s scheduled release of wastewater from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in 2023.

March 24, 2022: South Korea’s Special Representative for Korean Peninsula Peace and Security Affairs Noh Kyu-duk and Director-General of the Japanese Foreign Ministry’s Asian and Oceanian Affairs Bureau Funakoshi speak on the phone and call out North Korea’s firing of a ICBM for breaking its self-imposed moratorium on ICBM testing.

March 28, 2022: President-elect Yoon meets Japanese ambassador to South Korea Koichi Aiboshi and calls for Korea-Japan relations to improve in a “future-oriented way” and for it to be “urgently restored to a good relationship as before.”

March 30, 2022: Japan’s Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology announces completion of textbook screenings for next year, with removal of words such as “wartime” and “forced” from some history textbooks. The South Korean foreign ministry protests the decision by summoning the deputy chief of mission of the Japanese embassy in Seoul Kumagai Naoki, calling it a distortion of history, a claim rejected by the Japanese.

March 31, 2022: Kim Eun-hye, spokeswoman for President-elect Yoon reiterates that Yoon’s stance against Japan’s distortion of history remains unchanged, after some criticisms that he did not directly condemn the recent Japanese action to change some of their history textbooks.

March 31, 2022: President-elect Yoon’s spokeswomen Kim clarifies that while the Yoon administration will seek stronger security cooperation with the US and Japan, it will not seek to hold trilateral combined military exercises.

April 1, 2022: Japan announces additional sanctions against North Korea in response to its ICBM launch last week. The new sanctions target six North Koreans, three Russians and four Russian entities for their involvement in North Korea’s nuclear and missile program, subjecting them to an asset freeze.

April 2, 2022: Four-day “Non-Freedom of Expression Exhibition 2022” opens in Tokyo, featuring the Statue of Peace, which is a statue symbolizing comfort women.

April 15, 2022: South Korean government officially approves plan to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). This would become the second FTA with both Korea and Japan as members, after the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

April 17, 2022: President-elect Yoon announces plans to send a special delegation to Japan from April 24-28 for policy consultations. The delegation will be led by five-term lawmaker and vice National Assembly Speaker Chung Jin-suk. This will be Yoon’s second special delegation, after the one that visited the US in early April.

April 25, 2022: South Korean special delegation meets Hayashi and Trade Minister Hagiuda Koichi and discusses bilateral issues and export controls.

April 26, 2022: South Korea’s special delegation meets Prime Minister Kishida. He says “there is no time to waste in improving Japan-South Korea relations” and reiterates that “strategic cooperation between Japan and South Korea, and among Japan, the US and South Korea, is more necessary than ever.”