Articles

“Cold economics, cold politics” has become the new normal in Japan-South Korea relations. Instead of the practical stability that they maintained in the first months of this year, latent tension became the defining force as Seoul and Tokyo followed through their earlier decisions made in 2018 and 2019. The twin decisions—South Korea’s Supreme Court ruling on forced labor during Japan’s occupation of the Korean Peninsula and Japan’s export restrictions on key materials used for South Korea’s electronics industry—planted the seeds of discord and deterioration of bilateral ties during the summer months of 2020. In June, following the 2018 Supreme Court’s order, the Daegu District Court released a public notice to Nippon Steel, formerly known as Sumitomo Metal, a move to seize and liquidate the local assets of the company. In response to Japan’s imposition of export controls in 2019, South Korea filed a complaint with the World Trade Organization. This downward spiral will likely continue for the remainder of the year unless South Korea and Japan take decisive action to address these disputes. On the North Korea front, Japan’s newly published Defense of Japan 2020 assessed North Korea’s nuclear and missile capabilities as posing greater threats to Japanese national security than previous years.

Japan’s 2020 Defense White Paper and North Korea

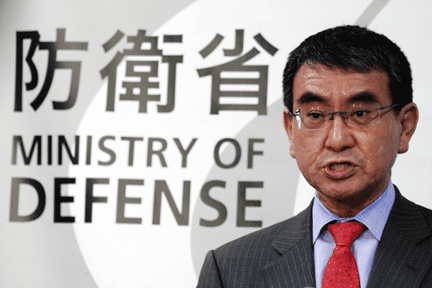

Defense of Japan 2020 is noteworthy for its assessment that “North Korea is considered to have miniaturized nuclear weapons to fit in ballistic missile warheads and to possess the capability to launch an attack on Japan with a nuclear warhead.” To counter North Korea’s missile capabilities, Japan had a plan to deploy a US-made Aegis Ashore missile defense system. However, in early June the Japanese government surprised many experts by announcing that it has decided to halt the plan. Japan’s decision to purchase two Aegis Ashore systems in December 2017 came after a flurry of North Korean missile launches, along with pressure from the Trump administration. However, Defense Minister Kono Taro told Prime Minister Abe Shinzo that he would not pursue the plan, as it became clear that expected costs associated with modifications to the rocket booster to ensure sure that it would not fall on residential areas reached some 200 billion yen ($1.89 billion) while taking as long as 12 years to complete.

Figure 1 Defence Minister Taro Kono cited technical and cost issues in his plan to halt the deployment of US-made Aegis Ashore missile defense system Photo: AP

Japan is considering alternative plans with a panel of experts who are also discussing revisions of Japan’s National Security Strategy. Meanwhile, its missile defense will focus on the Maritime Self-Defense Force’s (MSDF) Aegis destroyers’ SM-3 interceptor missiles. Abe sought to advance the idea again that Japan should consider acquiring a preemptive strike capability within the limitations of the Japanese pacifist constitution. While it remains to be seen how Japan proceeds with a new national security strategy, Japan’s choices will likely have implications for broader regional security, as well as its alliance with the United States.

COVID-19 Diplomacy and Japan’s Diplomatic Bluebook

In early May, the story of Japan assisting a young South Korean girl who had acute leukemia to return home in South Korea from India was a heartwarming episode that thawed frosty Seoul-Tokyo relations, albeit temporarily. As the COVID-19 pandemic suspended all flights from India to Seoul Korea, the South Korean Embassy in New Delhi appealed to other countries for help and the Japanese Embassy responded by arranging a special Japan Airlines flight. South Korean Foreign Minister Kang Kyung-wha sent a letter of appreciation to her Japanese counterpart Motegi Toshimitsu. This story received wide media coverage in both countries.

Another potentially positive sign in May was that the 2020 Diplomatic Bluebook of Japan again referred to South Korea’s place in Japanese foreign policy as “an important neighboring country,” which hinted at Tokyo’s desire to stop further deterioration of bilateral relations with Seoul. In a press conference on May 19, Motegi commented that the bluebook should be read “from the perspective of the current direction of Japan’s diplomacy.” He went on to say that “Regarding Japan-ROK relations, there have been various circumstances concerning our two countries since last year, including good and bad. The aforementioned phase was used taking all that into account.” The 2017 Diplomatic Bluebook had previously described South Korea as “Japan’s most important neighbor that shares strategic interests with Japan,” but that reference was omitted in 2018 and 2019. The same 2020 Diplomatic Bluebook simultaneously signaled that there was no change in the Japanese government’s claims over the Dokdo/Takeshima islets, which led the South Korean government to protest strongly. When Defense of Japan 2020 repeated their claim over the Dokdo/Takeshima islets, South Korea again reiterated its claim and protested the Japanese government position.

Simmering Tensions—Forced Labor and Export Control

Over the summer of 2020, the intertwined issues of history and trade were at the heart of heated contestation between Tokyo and Seoul. On June 1, South Korea’s Daegu District Court released a public notice to Nippon Steel with a ruling to seize and liquidate the company’s local assets. The seizure order focused on PNR, a joint venture between Nippon Steel and POSCO. In August, Nippon Steel decided to appeal the court order. Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga Yoshihide said that the Japanese government will respond firmly and consider various countermeasures.

Figure 2 The photos of four Korean victims of forced labor are displayed by South Korean and Japanese activists outside Nippon Steel’s Tokyo headquarters in November 2018 Photo: Hankyoreh archives

In June, South Korea’s Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE) filed a petition against Japan with the World Trade Organization (WTO) dispute settlement procedures. About a year earlier in July 2019, the Japanese government had placed export restrictions on hydrogen fluoride, fluorinated polyimide, and photoresists on national security grounds, asserting that South Korea had inadequate manpower and screening techniques and failed to strictly control illegal exports. This move was widely interpreted in South Korea as retaliation to the 2018 South Korean Supreme Court ruling on forced labor. In September 2019, South Korea lodged a complaint with the WTO, but in November the two sides agreed to hold bilateral consultations and postpone WTO dispute settlement procedures.

In May of this year, South Korea’s MOTIE notified Japan that it addressed the issues raised by Japan and requested that Japan clarify its position by the end of the month. Director-General Kim Jung-han of South Korea’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs “urged the Japanese government to promptly withdraw unjust export-restrictive measures” during his talk with Japanese counterpart Takizaki Shigeki of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. When South Korea decided that Japan had failed to keep its side of the bargain, it went ahead with the petition at the WTO, which led Japan to express “dismay” at Seoul’s decision. In late June, the WTO Dispute Settlement Body agreed to set up an arbitration panel. A final ruling on the dispute can take about 10-13 months or longer. In late June, the Japanese government launched an anti-dumping investigation into imports of potassium carbonate from South Korea, which is used for liquid crystal panels.

After South Korea filed the WTO complaint against Japan, South Korean Trade Minister Yoo Myung-hee’s bid to become WTO director general became a topic of discussion within Japan, while some in South Korea speculated that Japan might try to block Yoo’s candidacy. Japanese Trade Minister Kajiyama Hiroshi remarked, “It’s important that [the WTO director-general] be a person capable of exercising leadership in the COVID-19 response and WTO reform. In that respect, Japan wants to be definitively involved in the election process.” In a press conference after her hearing, which is part of the application process for the WTO position, Yoo asked to be evaluated by her credentials “rather than from the perspective of the disputes.” She said, “When they actually look at the candidates, to Japan, what’s utmost important is the person’s, the candidate’s, competency and capability to save and enhance the WTO, and also to take up WTO reform. So in this regard, I will reach out to Japanese colleagues and will present my vision for the WTO.”

In late May, Japan’s reaction to the proposal by President Trump that South Korea be invited to the upcoming G7 summit—an invitation that South Korean President Moon Jae-in accepted—received much media attention in South Korea. According to Kyodo News in late June, a high-ranking Japanese official reached out to the United States and conveyed the message that Japan was against Seoul’s participation on the basis that Seoul held differing diplomatic positions on China and North Korea from the G7. Suga said, “It’s very important to maintain the G7 framework.” While Tokyo’s opposition was widely viewed as an attempt to maintain its status as the only Asian member of the G7, a high-ranking South Korean official at the Blue House was reported to have said, “It is shameless for the Japanese government to attempt to obstruct President Moon Jae-in’s attendance at an event to which he was formally invited. This is unthinkable behavior from our neighbor.”

Contentious Politics of Official Narratives

In international politics, states are constantly constructing official narratives about who they are through interpretations of the past. According to Thomas Berger, they find concrete expressions in multiple domains of government policies, including rhetoric (how political leaders and public intellectuals talk about the past), commemoration (i.e., museums, monuments, and holidays), education (i.e., history textbooks), compensations (policies that are geared toward helping victims of past injustices), and punishment (policies that restrict freedom of speech and deal with perpetrators of injustice). Generally speaking, difficulties in bilateral relations between South Korea and Japan had much to do with colliding interpretations of the two sides’ official narratives about their shared past.

This summer, in conjunction with the dispute over compensation issues, Japan’s Industrial Heritage Information Center in Tokyo and the narratives that Japan associated with it to commemorate the history of industrial revolution intensified Seoul-Tokyo diplomatic friction. In 2015, UNESCO granted World Heritage status to 23 industrial facilities related to Japan’s industrialization. At that time, during a UNESCO World Heritage Committee meeting in Bonn in July 2015, Japan promised that the history of Koreans conscripted for forced labor during Japan’s occupation of the Korean Peninsula would be part of the commemoration. When the contents of the exhibits were made available to the press in June, they prompted sharp criticism from South Korea. The South Korean daily Choson Ilbo reported, “the exhibits feature interviews with around a dozen people who worked on Hashima Island and glorify its history. Pay envelops are also on display in an attempt to prove that Korean laborers were rewarded properly.”

On June 15, South Korea’s First Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs Lee Tae-ho summoned Ambassador Tomita Koji to lodge a protest over the omission of Korean forced laborers. On June 22, the South Korean government formally submitted a request to UNESCO that these sites be removed from the World Heritage list. The Japanese government responded by saying that South Korean criticisms are “unacceptable.” Center director Kato Koko said, “We interviewed over 70 island residents, and none of them said they had suffered abuse.” Sixty-four South Korean and Japanese civic groups issued a statement calling on the Japanese government to “honor the promise it made when it registered the Meiji Industrial Revolution-related facilities as UNESCO Heritage Sites in 2015.”

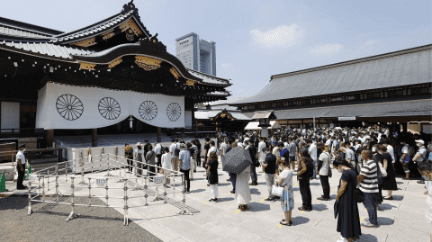

Figure 3 People praying at Tokyo’s Yasukuni shrine while maintaining social distancing amid the coronavirus pandemic. Photo: Kyodo

On Aug. 15, four Cabinet ministers of Japan visited the Yasukuni Shrine, while in South Korea the National Archives of Korea, the National Library of Korea, and the Northeast Asian History Foundation released documents produced during Japan’s occupation of the Korean Peninsula related to Japan’s conscription of Koreans, especially women and children, for forced labor.

During the summer, a civic group that has led a weekly rally every Wednesday near the Japanese Embassy calling for Japan’s apologies for the so-called “comfort women” issue was at the center of scandals in South Korean domestic politics. Allegations surrounding this group, Korean Council for Justice and Remembrance for the Issues of Military Sexual Slavery, included misappropriation of donations from South Koreans. Yoon Mi-hyang, its former president who was elected as a proportional representative in the South Korean National Assembly in April, denied the allegations. She was summoned for questioning as prosecutors began investigating in May. This received Japanese media attention but did not become a diplomatic issue between the two countries.

Economic Relations

A year after Japan’s export restrictions, the South Korean government evaluated that disruptions and setbacks to South Korean economy have been limited. President Moon Jae-in said in a Cabinet meeting that “so far there have been no production setbacks… It [Japan’s export controls] has spearheaded the localization of materials, parts and equipment as well as establishing a diverse and stable supply chain.” In January, it was reported that Dupont, a US company, will build a manufacturing plant for photoresis, one of the three chemicals that Japan placed export restrictions on, in South Korea. It is expected that South Korea will continue to seek localization and diversification strategies.

A movement within South Korea to boycott Japanese products in response to Japan’s export restrictions has been waning but South Korean consumption patterns. According to Korea Customs Service data, in April 2020, imports from Japan constituted 297 billion won ($248 million), 30% less than April 2019. Compared to the same period last year, sales of Japanese products dropped 35% in January 2020, 14.9% in February, and 17.7% in March. Sales of Japanese beer and cars are among the hardest hit. In April 2020, Japanese beer sales dropped 88% from the last year. Similarly, Japanese car sales dropped to 7,308 units from January to May 2020, a 62.6% decline from the previous year. Yet all was not bad: other Japanese consumer brands opened stores in South Korea as they saw increases in sales.

Overall, both South Korean and Japanese economies are struggling. South Korea went into a technical recession in the second quarter, like Japan, Thailand, and Singapore, as the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected its economy. According to the Bank of Korea, South Korea’s GDP shrank 1.4% in the first quarter and 3.3% in the second quarter. This was South Korea’s worst performance since 1998. Japan’s economy also plunged into a recession. According to the Cabinet Office of Japan figures, Japan’s GDP shrank by an annual 2.2% in the first three months of 2020, marking a technical recession for the first time since 2015, followed by an annual 7.8% contraction in the second quarter, as the pandemic hit Japan as well.

Looking Ahead

At a deeper level, distrust—defined as “regard with suspicion; doubt the honesty or reliability of”—has been shaping these countries’ actions and messages this summer. It remains to be seen whether either of the two upcoming developments—Abe’s resignation and leadership change in Japan and the US presidential election in November—will provide the two countries with opportunities to create new momentum for their relations.

Chronology prepared by Patrice Francis.

May 1, 2020: North Korean leader Kim Jong Un makes first public appearance in 20 days amid health rumors.

May 12, 2020: South Korea’s Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE) urges the Japanese government to clarify its stance about resolving white list issue and three products under export controls.

May 13, 2020: South Korean Ministry of Foreign Affairs Director-General of Asian and Pacific Affairs Kim Jung-han and Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs Director-General Takizaki Shigeki discuss Japan’s export controls on semiconductor materials, the South Korean Supreme Court’s ruling ordering compensation for victims of forced labor, and COVID-19 during a phone call.

May 19, 2020: The 2020 Diplomatic Bluebook of Japan says “South Korea continues to illegally occupy Takeshima with no basis whatsoever,” referring to Dokdo/Takeshima islets.

May 19, 2020: South Korean Ministry of Foreign Affairs responds by saying, “We strongly protest the Japanese government’s reiteration of its unjustified territorial claims regarding Dokdo.”

May 24, 2020: North Korean state media reports that North Korean leader Kim Jong Un convened a military meeting to discuss bolstering North Korea’s nuclear arsenal.

May 30, 2020: President Trump invites South Korea, Australia, India, and Russia to G-7 meeting on the ground that the current makeup of G7 nations is “a very outdated group of countries.”

June 1, 2020: Following the 2018 South Korean Supreme Court ruling, Daegu District Court releases a public notice to Nippon Steel with ruling to seize and liquidate company’s local assets.

June 2, 2020: South Korea’s MOTIE says it will resume filing a WTO complaint over Japan’s export controls during press conference.

June 4, 2020: Japan Defense Minister Kono Taro meets with Prime Minister Abe Shinzo to discuss Aegis Ashore ballistic missile defense system.

June 14, 2020: Japan’s Industrial Heritage Information Center in Tokyo’s Shinjuku ward opens to press.

June 15, 2020: Kono tells reporters that he has given instructions to suspend deployment of Aegis Ashore missile defense system.

June 15 2020: South Korea’s First Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs Lee Tae-ho summons Japanese Ambassador Tomita Koji and protests omission of Korean forced labor victims in Industrial Heritage Information Center.

June 18, 2020: Abe says, “We should renew our discussion of adequate deterrence we need, considering North Korea’s missile technology that has advanced since the time we introduced our missile defense systems.”

June 22, 2020: South Korean government submits letter asking UNESCO to consider revoking World Heritage site registration for Hashima Island.

June 25, 2020: Kono announces decision to abandon plans for Aegis Ashore missile defense system.

June 28, 2020: Kyodo News Agency reports that immediately after President Trump’s May announcement a senior Japanese official communicated to US that South Korea’s “diplomatic position on China and North Korea differs from the G7” and Japan “opposes South Korea’s participation” for this reason.

June 29, 2020: High ranking Blue House official says, “It’s shameless for the Japanese government to attempt to obstruct President Moon Jae-in’s attendance at an event to which he was formally invited. This is unthinkable behavior from our neighbor.”

June 29, 2020: Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga Yoshihide says “It’s very important to maintain the G7 framework” during daily press briefing.

June 29, 2020: Jiji Press reports that Japan has started investigation into possible dumping of potassium carbonate by Korea.

July 7, 2020: Japanese Trade Minister Kajiyama Hiroshi says “It’s important that [the WTO director-general] be a person capable of exercising leadership in the COVID-19 response and WTO reform. In that respect, Japan wants to be definitively involved in the election process” during daily press briefing.

July 14, 2020: Defense of Japan 2020 claims the Dokdo/Takeshima islets as Japanese territory. It also states that “North Korea is assessed to have already miniaturized nuclear weapons to fit ballistic missile warheads.”

July 14, 2020: South Korean Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson calls for an immediate withdrawal of Japan’s claims over the Dokdo/Takeshima islets.

July 16-17, 2020: Japan and South Korea takes part in multilateral anti-piracy drill by the European Union Naval Force Somalia in the Gold of Aden.

July 28, 2020: During press briefing Suga responds to reports of a statue of a kneeling man, seemingly representing Abe, before a statue of a comfort woman at Korea Botanic Garden in Gangwon by saying, “If the reports are true, I believe this could decisively effect Korea-Japan relations.”

July 29, 2020: WTO Dispute Settlement Body begins review of Japan’s export restrictions.

Aug. 1, 2020: During appearance on Yomiuri TV Japan’s Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga says Japanese government is “reviewing all responses to [liquidation]” if Korean court order for seizure of Nippon Steel assets proceeds as scheduled.

Aug. 4, 2020: Daegu court serves notice to Nippon Steel that assets will be seized to compensate wartime forced labor victims.

Aug. 4, 2020: During a press conference Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson Kim In-chul says “GSOMIA is something that can be terminated at any time.”

Aug. 7, 2020: Nippon Steel appeals Daegu court decision for seizure of assets.

Aug. 13, 2020: National Archives of South Korea releases documents showing Japan’s mobilization of Korean girls and women into forced labor.

Aug. 15, 2020: President Moon Jae-in says “The government is prepared to sit down with the Japanese government at any time” during the celebratory address of the anniversary of Korea’s liberation from Japan’s colonial occupation.

Aug. 15, 2020: Environment Minister Koizumi Shinjiro, Education Minister Hagiuda Koichi, State Minister for Okinawa and Northern Territories Eto Seiichi, and Internal Affairs Minister Takaichi Sanae visit Yasukuni Shrine on the anniversary of Japan’s defeat in World War II.

Aug. 28, 2020: Abe holds news conference to formally announce intention to resign and states he is “no longer in a condition to confidently respond to the mandate given to him by the public.”