Articles

PRC State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s November visit to Seoul produced limited substantive results while signaling Beijing’s deeper strategic intentions toward the United States’ Asian allies. China’s commemorations of the Korean War’s 70th anniversary in October provided reassurances to North Korea while triggering a war of words with South Koreans, ranging from the foreign ministry to the K-pop group BTS. On social media, the history controversy was a prelude to wider cultural clashes on a host of issues. While the repercussions of COVID-19 and US-China trade tensions challenge China and South Korea’s economic agenda, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership’s signing in November raised prospects for regional multilateralism. Meanwhile, North Korea’s self-imposed quarantine resulted in a precipitous drop in North Korean imports from China according to China’s official trade statistics. UN Panel of Experts-led monitoring of North Korean off-the-books exports of coal and sand to China drew harsh US criticisms and catalyzed the announcement of a US Treasury-administered rewards program for reporting on primarily Chinese entities engaged in illicit trade with North Korea. Coupled with the incoming Biden administration’s envisioned regional architecture and the campaign’s declared reliance on multilateral approaches to North Korea, Asia’s multilateral initiatives may heighten Seoul’s US-China dilemma.

Wang Yi’s Visit to Seoul: ‘Shared Aspirations’ or ‘Unanswered Courtship?’

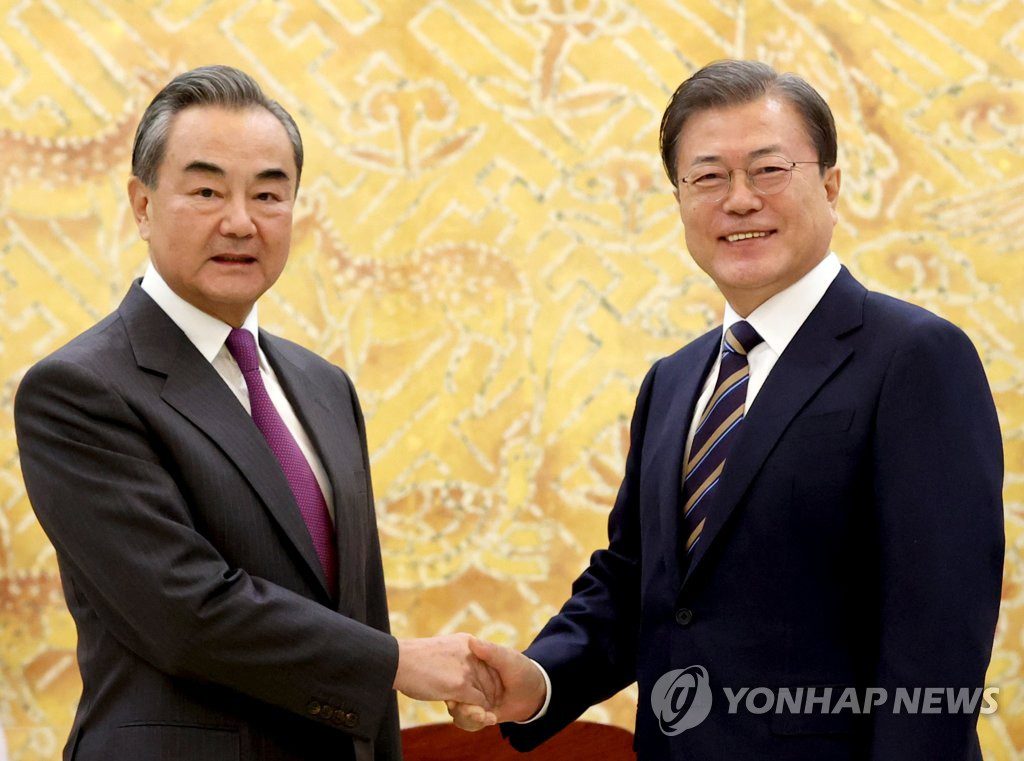

Wang Yi’s Nov. 25-27 visit to Seoul included meetings with President Moon Jae-in, Foreign Minister Kang Kyung-wha, National Assembly Speaker Park Byeong-seug, Special Presidential Advisor for Foreign and Security Affairs Moon Chung-in, and ruling party leaders. Paired with Wang’s Tokyo visit, it was widely perceived as an effort to consolidate ties with US allies ahead of the Biden administration’s inauguration. The visit fell short of South Korean expectations for a Xi-Moon summit in Seoul by the end of 2020. Wang conveyed Xi’s message of “personal friendship and mutual trust” to Moon, and reminded his counterpart Kang that “the US is not the only country in this world.” To Park, Wang expressed support for an inter-Korean peace process without external interference, stating, “the fate of the peninsula should be given to the two countries.” He championed multilateralism over “neo-Cold War” during talks with Moon Chung-in. According to China’s state media, Wang’s Northeast Asia tour demonstrated “regional cohesion” and “resilience against outside pressure.” His Seoul visit in particular forged a “model for practical diplomacy” signifying “shared aspirations” of “strategic partners.” As Wang claimed, “My visit to South Korea … is intended to show the importance we attach to China-South Korea relations through actual action.”

Figure 1 Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi meets South Korean President Moon Jae-in in Seoul. Photo: Yonhap

China’s foreign ministry released a 10-point consensus between Wang and Kang on Nov. 26, pledging cooperation on COVID-19, cultural exchanges, development and trade, peninsula peace and stability, and dialogue mechanisms. Seoul’s version of the meeting outcome did not include Beijing’s envisioned “2+2” dialogue on diplomatic and security affairs. A Korea Herald editorial on China’s “unanswered courtship” argued that Wang “was lavish in his rhetoric … but failed to commit to substantial measures.” The Dong-A Ilbo noted “no progress” in Beijing’s THAAD demands and restrictions on Korean cultural content. While Korean observers largely dismissed the “consensus” for lacking substance, even liberal outlets like Hankyoreh appeared wary of Beijing’s deeper intentions of “recruiting Seoul to its side.” As Kim Heung-kyu at Ajou University argued, the most important reason for Wang’s visit was “US-China strategic competition.” A Korea Times editorial concluded that “Wang Yi’s visit raises both hope and anxiety,” requiring “flexible diplomacy” that can “strike a balance between Beijing and Washington.”

PRC and ROK officials discussed a range of issues reaffirming the Xi-Moon agreements from December 2019. Telephone talks were held on Sept. 10 between nuclear envoys Luo Zhaohui and Lee Do-hoon, and on Oct. 21 between defense ministers Wei Fenghe and Suh Wook. Fisheries officials on Nov. 6 and Dec. 17 agreed to reduce fishing boat quotas in exclusive economic zones (EEZs) and strengthen responses to illegal fishing. According to Korean lawmakers, the number of reported cases of China’s illegal fishing in ROK waters more than doubled in 2017-2019, and PRC warships crossing the EEZ median line represented almost 80% of cases in 2019. In video talks with PRC counterpart Le Yucheng on Dec. 23, Vice Foreign Minister Choi Jong-kun also raised concern over China’s entry into South Korea’s KADIZ during China-Russia air exercises. In more positive developments, foreign ministry officials held video talks on Nov. 9 ahead of ASEAN summits marking RCEP’s signing. Environment ministers Huang Runqiu and Cho Myung-rae held virtual talks on Nov. 11, citing Xi and Moon’s recently announced plans to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 and 2060 respectively.

As seen during Wang Yi’s visit, recent bilateral meetings received Korean media attacks on China’s “arrogance” and Moon’s “submissive” leadership. As a Korea Herald editorial argued after the apparent suspension of Samsung-chartered flights to China in November: “China’s arrogance toward Korea is a problem, but as problematic is the submissive attitude of the Moon administration.” A Dong-A Ilbo article on ultrafine dust pollution from China similarly urged Seoul to “abandon its submissive attitude.”

Commemorating the War to Resist US Aggression …

The Korean War’s 70th anniversary, sixth in Xinhua’s top 10 China news events in 2020, appeared to draw more attention from Beijing than did the 70th anniversary events of World War II in 2015. Commemorations reflected what Zhao Ma at Washington University in St. Louis described as the Korean War’s evolution “from a socialist crusade to a nationalist mission” in China’s national memory. After a six-year closure, China’s only Memorial Hall centered on the war reopened on Sept. 18 in Dandong, displaying: “On June 25, 1950, the Korean civil war broke out.” During a visit to a Korean War exhibition at the Beijing Military Museum of the Chinese People’s Revolution on Oct. 19, President Xi remembered the war as “a victory of justice, a victory of peace and a victory of the people.” Vice President Wang Qishan and all CPC Politburo Standing Committee members accompanied him. In his Oct. 23 address in Beijing, Xi stated that “China will not compromise on its national sovereignty, security and interests,” noting current “challenges of unilateralism, protectionism and hegemonism.” As Global Times reported, Xi’s speech “delivered a clear message that the attempt by the US and any other forces to contain China will never succeed.”

Figure 2 Memorial Hall of the War to Resist US Aggression and Aid Korea reopens in Dandong. Photo: Xinhua

In South Korea’s seventh return since 2014, the remains of 117 Chinese soldiers of the Korean War arrived on Sept. 27 in Shenyang. Vice Premier Sun Chunlan and Minister of Veteran Affairs Sun Shaocheng addressed two-day events leading to Martyrs’ Day, including what Global Times called the “state’s highest greeting ceremony” signaling that China will “fight hegemony till end.” As Li Jingxian at the Ministry of Veterans Affairs emphasized, the PLA aircraft used to repatriate the remains embodied China’s stronger “national image.” According to Lyu Chao at the Liaoning Academy of Sciences, the latest exchange reflected China’s “friendly and peaceful settlement” with South Korea and “undeniably stronger” ties with North Korea. Xi’s history discourse prompted the ROK Foreign Ministry to issue a statement on Oct. 24 reaffirming Seoul’s position: “That the Korean War broke out due to North Korea’s invasion is an undeniable historical fact.” The Communist Youth League of China’s Weibo comments a day later prompted the ministry to reiterate this position on Oct. 28. A Korea Times editorial on Oct. 26 responded to Seoul’s “lukewarm reaction,” arguing, “Xi deserves criticism … we urge Xi to face up to history and respect South Korea.” South Korea’s backlash came a month after Moon proposed an end-of-war declaration in a speech at the UN General Assembly, reviving debate over China’s role. PRC Ambassador Xing Haiming told JoongAng Daily on Oct. 14, “China cannot be left out of the process.”

China’s state and popular platforms disseminated official narratives of the Korean War throughout October. The Foreign Languages Press and Military Science Publishing House released the English edition of The War to Resist US Aggression and Aid Korea, “a Chinese interpretation and justification of the war” according to a Global Times review. In a Global Times article on Oct. 1, China’s National Day, PLA Lt. Gen. He Lei argued, “revisiting the essence of China’s strategic decision-making … is of great significance to the continuous victory.” CGTN featured interviews of war veterans claiming, “our army isn’t like the one before.” A Global Times editorial on Oct. 22 concluded: “When China was very poor, it didn’t surrender to US pressure and stood out to resist and finally defeat the US on the Korean Peninsula. Today, China has grown to be a strong country, so there is no reason for China to fear the US threats and suppression.” Popular commemorations included CCTV documentaries and TV series, plays and dance shows, an animated film, and The Sacrifice, which led mainland China’s box office for four weeks. According to China’s state media, filmmaker Zhang Yimou’s The Coldest Gun will promote “patriotic sentiments” and “courage and determination in response to the US’ increasing aggression.”

A CGTN commentator dismissed global reactions to the state propaganda-led “War of Words,” asking, “why do media suggest China wants war when it commemorates peace?” International debate centered on the repercussions of Beijing’s nationalist discourse on public diplomacy with Seoul amid ongoing US-China tensions. The Voluntary Agency Network of Korea stated in a Change.org petition in September, “We oppose the extreme attitude of attacking others in the name of nationalism.” Comparing Chinese, Korean, and Japanese nationalism, Park Won-gon at Handong Global University told The Korea Times, “Chinese patriotism is different from the two others’ as it is mainly government-driven.” At the paper’s 70th anniversary ceremony on Oct. 29, US Ambassador Harry Harris reflected on the Korean War by stating, “our two nations’ commitment and resolve to democracy was put to the test … the fight for democracy has continued in other equally crucial ways off the battlefield.”

… And Aid, Not Trade, With North Korea

While the topline message from Xi’s commemorative speech on the 70th anniversary of the Korean War emphasized China’s capability and will to resist US aggression, the accompanying signal of support to North Korea—even if it was a by-product of Xi’s efforts to harness Chinese nationalism in response to perceived modern-day US aggression—were well-received by Kim Jong Un. The consolidation of formal China-North Korean ties has been reflected primarily in reaffirmation around commemorative dates of an active public correspondence between Xi and Kim in light of the focus on Trump-Kim “love letters” and revelations of an active but seemingly ineffectual correspondence between Kim and Moon. Xi and Kim regularly exchanged well-wishes on major anniversaries including the 71st anniversary of the founding of the PRC and the 75th anniversary of the founding of the Korean Workers’ Party. Reporting on this correspondence as well as exchanges of floral baskets between top party institutions and with associations of overseas Koreans in China signified the restoration of an active and close relationship between the two countries. Placing a spotlight on these symbolic exchanges at the individual and institutional levels evokes memories of the longstanding special relationship between the two countries throughout the Cold War.

Kim Jong Un reinforced images of a close China-North Korea relationship by making a visit to the Cemetery of the Martyrs of the Chinese People’s Volunteers and to the grave of Mao Zedong’s son, Mao Anying, a casualty of the Korean War. The restoration of closer China-North Korea relations follows North Korea’s active and vocal support over the summer for the promulgation of a new National Security Law for Hong Kong as a defense of China’s sovereignty and coincides with the downturn in China-US relations. In this respect, historical commemoration of China’s role in the Korean War is intricately linked with rising Chinese nationalism and the downturn in China-US relations.

The most significant revival of Chinese aid to North Korea was documented by the UN Panel of Experts, which reported on apparent breaches of UN Security Council mandated caps on North Korean exports of coal and import of refined petroleum through ship-to-ship transfers and direct deliveries. While UN diplomats quibbled over whether limits on petroleum transfers to North Korea should be measured in barrels or metric tons, North Korean ships were recorded by satellite and other means engaging in increasingly brazen and regular traffic to Chinese territorial waters and ports. Despite photographic and satellite evidence of being caught red-handed, Chinese and North Korean authorities brushed off international criticisms, resulting in significant volumes of North Korean exports in breach of UN sanctions that blew a gaping hole in the UN sanctions regime.

Deputy Assistant Representative Alex Wong stated in a public speech on Dec. 22 that the United States had provided information to Chinese Navy or Coast Guard vessels information regarding DPRK fuel smuggling into Chinese coastal waters on 46 separate occasions, and that the US had observed ships carrying UN-prohibited coal or other sanctioned goods from North Korea into China on 555 separate occasions. Chinese diplomats called for lifting sanctions on North Korea while enabling significant sanctions evasion, rewarding North Korea’s leadership by meeting primary demands that the US had disregarded at the US-North Korea summit in Hanoi, but with no apparent Chinese insistence on North Korean denuclearization quid pro quos. After months of mounting US frustration over China’s non-adherence to the sanctions regime, the US announced a rewards plan of up to $5 million for reporting of violators of UN sanctions on North Korea.

Given China-North Korea sanctions evasion efforts, the accuracy of Chinese records of official economic transactions with North Korea was subject to scrutiny and doubt. But even if Chinese statistics were unrepresentative of the reality of China’s exports to North Korea, the sudden and prolonged drop in official North Korean exports to China resulting from North Korea’s anti-COVID-19 self-quarantine efforts was striking. The level of officially recorded North Korean exports to China dropped in October by 92% from the previous month to $1.7 million, and recorded a drop through the first 10 months of 2020 from the previous year by as much as 76%. This decline exceeded the dramatic drop in recorded Chinese exports to North Korea that occurred at the height of the North Korean missile testing crisis at in 2017-2018. It also combined with exchange rate fluctuations between the won and dollar and the won and renminbi following an extended period of exchange rate stability, raising questions about what to expect in the run-up to the Eighth Party Congress in January 2021. North Korea’s efforts to raise foreign currency by floating domestic bonds in spring 2020 and the unreliability and continued lack of transparency of North Korea-related trade statistics made it increasingly difficult to make judgements about North Korea’s economic stability or the extent to which China may have provided subsidies designed to forestall North Korea’s economic collapse.

China-ROK Economic Plans: Post-Pandemic Challenges and Opportunities

Wang Yi’s November visit to Seoul reaffirmed plans to advance coordinated development, the bilateral FTA, and multilateral initiatives, supporting both partners’ quest to expand into emerging industries and third-party markets. His meeting with Foreign Minister Kang drew attention to a Joint Plan for economic and trade cooperation for 2021-2025, expected to facilitate post-pandemic recovery and China’s 14th Five Year Plan, according to Xiang Haoyu of the China Institute of International Studies. National Development and Reform Commission Chairman He Lifeng and ROK Finance Minister Hong Nam-ki discussed key bilateral issues on Oct. 16 before talks between trade officials on the FTA’s expansion. The China-ROK currency swap agreement’s five-year renewal that month raised prospects for trade and regional financial stabilization. Based on Korea International Trade Association (KITA) data, ROK exports to China reached $120 billion in January-November, a 3% decline compared to the same period last year, while imports amounted to $98 billion, a 0.2% decline. China’s share of South Korea’s foreign trade grew from 23% to 24%. While overall FDI in South Korea shrank by 22%, Chinese investment more than doubled to $856 million in the first half of 2020, increasing its share of FDI in South Korea from 3% to 11%. Chief of the KITA Beijing office Park Min-young reassured Global Times that Korean investment in China is likely to grow in the post-pandemic period. Zhang Huizhi at Jilin University also predicted a 70% recovery in South Korean exports to China in 2021, boosted by US trade restrictions on China.

Although the combined effects of COVID-19 and US-China trade tensions heighten the risks of dependence on China, Korean businesses are relying on Chinese and Southeast Asian markets to drive recovery. Seoul’s efforts to incentivize companies to relocate home from China, recently targeting the service and IT sectors, appear limited in impact. As the Financial Times reported in September, one survey showed that only 8% of 200 South Korean SMEs in China and Vietnam were willing to return. A KITA survey of more than 1,000 local exporters in October suggested cautious optimism: 20% anticipated the regional trade environment to improve the most in China, while 18% expected worsening trade terms with China.

In a November survey of 300 Korean manufacturers by the Korea Chamber of Commerce and Industry, 61% of respondents projected eased US-China trade tensions under the Biden administration. The implications of those tensions for South Korea are also mixed. US sanctions on Huawei raised concerns over the costs to chip exports to mainland China and Hong Kong, which together accounted for more than 60% of South Korean chip exports in January-July. But US restrictions may also imply long-term gains for rivals like Samsung, which reclaimed the biggest share of the global smartphone market by the third quarter of 2020, capturing 22% compared to Huawei’s 14%.

At the regional level, the Nov. 15 signing of RCEP boosted Wang Yi’s outreach in Seoul and Tokyo days later. RCEP’s signing was a “historic moment” according to Moon and a “victory of multilateralism and free trade” according to Premier Li Keqiang. China’s Commerce Ministry predicts that RCEP could increase exports among member countries by 10.4%, investment by 2.6%, and GDP by 1.8% by 2025. Chinese and Korean reactions focused largely on the implications for the United States’ regional position and trilateral relations with Japan. CGTN featured an opinion piece calling the deal a “fatal blow” to US regional initiatives, while China’s Commerce Ministry emphasized the acceleration of China-Japan-ROK FTA talks. China’s expression of interest in joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement on Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) paved the way for Moon to suggest that South Korea would also be interested in joining the CPTPP. But South Korean skeptics remain cautious about Beijing’s leadership of regional free trade and multilateralism, pointing to its “practice of resorting to economic coercion.” UNCTAD identified geopolitical and trade tensions as key challenges for RCEP-led regional integration.

Figure 3 Korean President Moon Jae-in and Chinese Premier Li Keqiang attend the virtual signing ceremony of the RCEP agreement. Photo: Xinhua

A Virtual Clash of Civilizations

Fueled by social media, Beijing and Seoul’s history controversy uncovered a much wider clash of identities at the societal level. Boy band BTS’ references to South Korea’s shared history with the United States after receiving the General James A. Van Fleet Award in October ignited outrage among Chinese netizens. In Korea, a petition on the Blue House website urged Seoul to ban Chinese artists who “distort the history of the Korean War.” After BTS became the first K-pop band to gain a Grammy nomination in November, Global Times noted the monetary contributions of Chinese fans known as ARMY, warning, “if Chinese are hurt a second time, it may cause a further loss of the Chinese ARMY members.”

Accusations of “cultural plagiarism” continued through the end of the year, against Seoul city’s annual celebrations of cultural exchange with China in October-December. To the surprise of Chinese observers, online clashes over traditional dress in early November sparked protests by Korean lawmakers and forced a Chinese mobile gaming company to close its Korean server. Producer Yu Zheng shared ancient Chinese paintings on Instagram with the comments: “Korea is China’s vassal state in the Ming Dynasty! Korean costumes are adopted from the Ming Dynasty! Here is the evidence!” The Hanfu vs. Hanbok debate coincided with Chinese uproar over K-pop band Blackpink’s handling of pandas, including the first South Korea-born panda cub Fubao. The panda debacle inspired the Weibo hashtag “why we cannot touch pandas with bare hands,” prompted China Wildlife Conservation Association to send a complaint to the zoo, and forced YG Entertainment to drop the reality TV show’s final episode.

Later confrontations extended to lantern lighting traditions featured in a Chinese TV drama. The Cultural Heritage of Administration of Korea boosted expectations for the approval of South Korea’s own Yeondeunghoe on UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity list, affirmed on December 16. Subsequent reports of Beijing’s certification from the International Organization for Standardization for pickled cabbage prompted South Korea’s Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs to draw a clear distinction between Korean kimchi and Chinese paocai. In a Yonhap News interview, Seo Kyoung-duk at Sungshin Women’s University urged the government and civil society to “take strong action against China’s moves to take cultural assets away from Korea.” The kimchi vs. paocai debate spiraled into online disputes over what Koreans netizens called Chinese attempts at “economic coercion.” Global Times traced paocai to the Three Kingdoms (220-280) period, claiming that 99% of napa cabbage in South Korea now comes from China. China’s foreign ministry denied awareness of the virtual feud, stating, “shared benefits surely outweigh that.” Asia Society Korea hosted a webcast two weeks later on “Beating the COVID-19 Blues with Homemade Kimchi,” featuring US Ambassador Harry Harris saying “there’s nothing more Korean than kimchi.”

2020’s virtual clashes ended on the Taiwan issue after Korean TV show Running Man featured adjacent PRC and ROC flags in a December episode. The segment prompted Chinese calls for a boycott and the episode’s removal online. As one Weibo user warned, “This is an issue that crosses the line for all Chinese people.” Sun Jiashan of the Chinese National Academy of Arts in a Global Times article in December called Korean entertainers’ attacks on China “a manifestation of cultural inferiority.” After months of public hostility, ROK Ambassador to Beijing Jang Ha-sung stressed the media’s role in “fostering the bonds of friendship” to “avoid unnecessary misunderstanding.” At the 12th China-ROK media dialogue in September, State Council Information Office Minister Xu Lin urged the media to “play the leading role of public opinion.” Some Chinese analysts described recent controversies as a “misunderstanding in translation,” reminding both sides, “the history of traditional Korean culture and Chinese culture are inseparable.”

Conclusion: Prospects under the Biden Administration

To mark their 30th anniversary, China and South Korea will celebrate Cultural Exchange Years 2021-2022 and create a committee for the next 30-year development of ties. As China’s foreign ministry indicated in November, the neighbors led regional cooperation in 2020 through COVID-19 prevention and control mechanisms and measures for resuming economic exchanges. 2021 confronts two challenges to post-pandemic relations: US-China tensions amid leadership transition in Washington, and cultural frictions undermining public diplomacy. Pew poll findings in October showed an increase in unfavorable views of China in South Korea from 63% to 75% in 2019-2020. Chinese are now wondering if “Biden’s diplomatic policy will drag South Korea into an alliance confronting China,” while South Koreans are bracing for Beijing’s “attempts to pull Korea away from its alliance with the US.”

Wang’s latest visit to neighbors sharpened attention on regional relations with Washington, where President-elect Biden seeks to consolidate US alliance networks in Asia. Addressing the Korea China Friendship Forum in Seoul on Nov. 19, PRC Ambassador Xing Haiming assured Koreans, “mutual beneficial cooperation will definitely supersede the zero-sum game; and multilateralism will definitely win over unilateralism.” Seoul’s US-China dilemma has raised calls for relying on multilateral frameworks as “strategic ambiguity” appears increasingly unsustainable. Washington and Beijing’s respective multilateralisms, however, may only heighten this dilemma. The Moon administration also faces growing pressure from his conservative opponents, which surfaced in October after ROK Ambassador to Washington Lee Soo-hyuck stated: “Just because South Korea chose the US 70 years ago doesn’t mean it must choose the US for the next 70 years.” According to Special Presidential Advisor Moon Chung-in, “shared values and historical continuity, while important, cannot take priority to the national interest.” As The Dong-A Ilbo suggests, “Biden-style internationalism based on rules and values … may put South Korea at the crossroads of unavoidable choices.”

Research assistance and chronology compilation provided by Chenglong Lin, San Francisco State University.

Sept. 5, 2020: Chongqing-Seoul international passenger flights resume, leading further post-COVID-19 flight resumptions between China and South Korea.

Sept. 7, 2020: South Korea’s First Vice Foreign Minister Choi Jong-kun holds separate meetings with PRC and Japanese ambassadors.

Sept. 9, 2020: President Xi Jinping sends a congratulatory message to Kim Jong Un on the 72nd anniversary of the DPRK’s founding.

Sept. 9, 2020: The 10th East Asia Summit Foreign Ministers’ Meeting and 21st ASEAN+3 Foreign Ministers’ Meeting are held online.

Sept. 10, 2020: Luo Zhaohui, China’s vice-minister of foreign affairs, and Lee Do-hoon, South Korea’s special representative for Korea Peninsula peace and security affairs, hold telephone talks.

Sept. 12, 2020: PRC Vice Foreign Minister Luo Zhaohui, ROK Foreign Minister Kang Kyung-wha, DPRK Ambassador to Indonesia An Kwang-il, and US Deputy Secretary of State Stephen Biegun attend the virtual 27th ASEAN Regional Forum.

Sept. 14, 2020: Kim Jong Un sends a reply message to Xi.

Sept. 14, 2020: A North Korean smuggler is shot dead while crossing the China-DPRK border.

Sept. 14, 2020: Changes to China’s national curriculum require northeast schools to replace Korean teaching material with Mandarin Chinese material according to local media reports.

Sept. 17, 2020: Disney’s Mulan premiere leads South Korea’s box office despite boycotts.

Sept. 18, 2020: China’s foreign ministry reiterates Beijing’s “dual-track approach” on the 15th anniversary of the September 2005 Six Party Talks Joint Statement.

Sept. 19, 2020: Memorial Hall of the War to Resist US Aggression and Aid Korea reopens in Dandong.

Sept. 25-26, 2020: Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, ROK Ministry of Education, and National Research Foundation of Korea host the 2020 China-Korea Humanities Forum.

Sept. 25, 2020: Sixth China-Japan-Korea Industries Expo starts in Weifang, Shandong province, where the China-Japan-Korea (Weifang) Industrial Park is launched.

Sept. 25, 2020: Minister of China’s State Council Information Office Xu Lin and ROK Culture Minister Park Yang-woo address the 12th China-ROK high-level media dialogue online.

Sept. 29, 2020: UN panel of experts reports on North Korea’s continued violation of UNSC sanctions.

Sept. 29, 2020: South Korea’s chief prosecutor Yoon Seok-youl and PRC Ambassador to Seoul Xing Haiming discuss law enforcement cooperation.

Oct. 1, 2020: Kim sends a message to Xi on the PRC’s 71st founding anniversary.

Oct. 10, 2020: Kim receives a message from Xi on the WPK’s 75th founding anniversary.

Oct. 13, 2020: PRC Vice Foreign Minister Luo Zhaohui attends ROK Embassy reception for South Korea’s National Foundation Day and Military Foundation Day.

Oct. 16, 2020: NDRC Chairman He Lifeng and ROK Finance Minister Hong Nam-ki hold online economic ministerial talks.

Oct. 16, 2020: The 2020 China-South Korea Outstanding Women’s Forum is held online.

Oct. 19, 2020: Xi Jinping and China’s top leaders visit Korean War exhibition at the Military Museum of the Chinese People’s Revolution in Beijing.

Oct. 19, 2020: Kim sends a reply message to Xi.

Oct. 20-Dec. 31, 2020: Seoul city holds its Eighth “China Day” celebrations online.

Oct. 21, 2020: PRC State Councilor and Defense Minister Wei Fenghe and ROK Defense Minister Suh Wook hold telephone talks.

Oct. 21, 2020: PRC Ambassador to the DPRK Li Jinjun attends a ceremony marking the 70th anniversary of the CPV’s entry into the Korean War.

Oct. 22, 2020: Ninth biennial ASEAN+3 Culture Ministers’ Meeting is held online.

Oct. 22, 2020: Kim Jong Un, accompanied by senior officials, visits the CPV cemetery in Hoechang County and lays a floral basket at the grave of Mao Anying, Mao Zedong’s son.

Oct. 22, 2020: The People’s Bank of China and Bank of Korea extend their currency swap deal.

Oct. 23, 2020: Xi addresses meeting marking the Korean War’s 70th anniversary. China and North Korea’s state media report on ceremonies at their memorial sites.

Oct. 23, 2020: Photo exhibition marking the Korean War’s 70th anniversary opens in Beijing.

Oct. 24, 2020: Kim Jong Un receives a reply message from Xi.

Oct. 26-30, 2020: China and South Korea hold ninth round of talks online on expanding the FTA’s scope.

Oct. 28-Nov. 30, 2020: A photo exhibition marking the Korean War’s 70th anniversary is held at the Military Museum of the Chinese People’s Revolution in Beijing.

Oct. 30, 2020: Direct flights from Seoul to Beijing resume.

Nov. 04, 2020: North Korea’s Tongil Sinbo emphasizes the country’s “special relationship” and “undefeatable friendship” with China.

Nov. 6, 2020: PRC and ROK fisheries officials agree to reduce fishing boat quotas in each other’s EEZ.

Nov. 9, 2020: ROK Deputy Foreign Minister Kim Gunn and PRC counterpart Luo Zhaohui hold video talks ahead of ASEAN-led summits.

Nov. 11, 2020: PRC and ROK environment ministers hold online talks.

Nov. 12, 2020: PRC foreign ministry denies reports about the suspension of Samsung’s chartered flight to China.

Nov. 14-15, 2020: President Moon Jae-in and Premier Li Keqiang attend virtual ASEAN+3 summit, East Asia Summit, and RCEP summit.

Nov. 19, 2020: The ASEAN Defense Senior Officials’ Meeting Plus is held online.

Nov. 19, 2020: The PRC Embassy and Korea-China City Friendship Association hold the China-ROK Friendship Youth Forum 2020 in Seoul.

Nov. 21, 2020: The 27th APEC Economic Leaders’ Meeting is held.

Nov. 25-27, 2020: PRC State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi visits Seoul.

Nov. 30, 2020: Liu Youbin, spokesperson for China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment, calls for strengthening cooperation with South Korea.

Dec. 2, 2020: RFA reports that North Korea has sent anti-aircraft units to the Chinese border.

Dec. 2, 2020: PRC foreign ministry responds to US accusations of DPRK sanctions violations.

Dec. 10, 2020: The 7th ASEAN Defense Ministers’ Meeting-Plus is held online.

Dec. 11, 2020: PRC, ROK, and Japanese health ministers hold annual talks online.

Dec. 17, 2020: China and South Korea hold working-level fisheries cooperation talks.

Dec. 23, 2020: ROK Vice Foreign Minister Choi Jong-kun and PRC counterpart Le Yucheng hold video talks.

Dec. 23, 2020: China’s foreign ministry affirms that Chinese and Russian aircraft “did not enter the airspace of other countries” in response to regional concerns over joint patrols.

Dec. 29, 2020: South Korea’s new chief nuclear envoy Noh Kyu-duk and PRC counterpart Wu Jianghao hold telephone talks.