Articles

Regional and global summits presented high-level platforms for China-South Korea engagement in November. The summitry showed that the relationship had returned with solidity with the resumption of international meetings and in-person exchanges. Although the Xi Jinping and Yoon Suk Yeol leaderships advanced diplomatic exchange, concerns emerged over enduring political and security constraints and growing linkages with the economic relationship. Kim Jong Un’s escalation of military threats, through an unprecedented number of missile tests this year, challenged Xi-Yoon bilateral and multilateral diplomacy. China-North Korea bilateral interactions, while brisk, primarily relied on Xi and Kim’s exchange of congratulatory letters around significant founding anniversaries, China’s 20th Party Congress, and expressions of condolences after the death of former Chinese leader Jiang Zemin. The UN Security Council’s failure to take unified action on DPRK threats prompted South Korea to voice frustration with China and expand cooperation with US and Japanese partners. Such responses only reinforced concerns raised in recent leadership exchanges, and Korean domestic division over Yoon’s diplomatic strategies.

The Xi-Yoon Summit and Multilateral Diplomacy

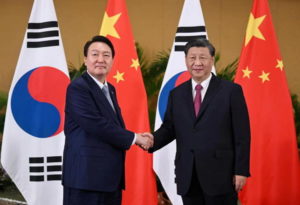

Figure 1 Presidents Xi and Yoon meet on the G20 summit sidelines in Bali. Photo: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China

Multilateral engagements in November fueled new China-ROK leadership exchanges after Yoon Suk Yeol took office in May as South Korea’s conservative leader, and Xi Jinping secured an unprecedented third term in October as Chinese Communist Party (CCP) general secretary. Yoon met Xi on the G20 sidelines in Bali on Nov. 15, and met Premier Li Keqiang at ASEAN summits in Phnom Penh on Nov. 12. Xi and Yoon reaffirmed earlier pledges on trust-building and common interests marking the 30th anniversary of diplomatic ties this year. The security implications of economic interdependence, North Korean aggression, and the broader regional order emerged as priority concerns lacking consensus. Xi raised the need to “oppose politicizing economic cooperation or overstretching the concept of security on such cooperation,” a growing source of friction on both sides. Yoon told Xi that “the diplomatic goal of the Korean government is to pursue the freedom, peace and prosperity of the international community based on common values and norms,” noting “China’s role is crucial” in this effort.

Through ASEAN’s platforms, Yoon presented Seoul’s Indo-Pacific strategy that embodied a rules-based order without excluding China, countering speculations over his administration’s closer alignment with Washington. While proposing a new Korea-ASEAN Solidarity Initiative to diversify economic partners, Yoon also called for reviving China-Japan-South Korea mechanisms that remained stalled due to bilateral tensions and COVID-19. US-China competition and post-pandemic uncertainty magnified regional challenges surrounding this year’s exchanges with ASEAN counterparts. In his speech commemorating the 25th anniversary of ASEAN+3 (APT) cooperation, Li called APT the “main vehicle of East Asian cooperation,” warned against “unilateralism and protectionism,” and reassured neighbors that “there is no reason for China to stop opening-up.” But resumed in-person meetings did not include a trilateral summit of Plus Three leaders, last held in December 2019 when China and South Korea’s last presidential summit was also held on the sidelines.

Meeting virtually on Dec. 12, Foreign Ministers Wang Yi and Park Jin committed to implementing the Xi-Yoon agreements and their own agreements from August talks in Qingdao, including the creation of a joint action plan for expanding bilateral ties. Defense Ministers Wei Fenghe and Lee Jong-sup met soon after the Xi-Yoon summit, on the sidelines of the ASEAN Defense Ministers’ Meeting-Plus in Cambodia on Nov. 23. In a step toward promoting defense exchanges, they agreed to resume the vice-ministerial defense strategic dialogue suspended since 2019. Environment Ministers Huang Runqiu and Han Wha-jin continued to advance regional cooperation, virtually holding the 23rd round of trilateral ministerial talks with Japanese counterpart Yamada Miki on Dec. 1. The virtual resumption of a business dialogue hosted by China Center for International Economic Exchanges and the Korea Chamber of Commerce and Industry on Dec. 12 followed Xi-Yoon agreements to expand public-private and high-level engagement.

Figure 2 China’s NPC Standing Committee head Li Zhanshu visits Seoul to meet President Yoon Suk Yeol and National Assembly Speaker Kim Jin-pyo. Photo: Yonhap

Despite those diplomatic achievements, the Yoon leadership still awaits a state visit by Xi. Yoon renewed the invitation during his Sept. 16 meeting with top legislator Li Zhanshu, the first National People’s Congress (NPC) Standing Committee chairman to visit South Korea since 2015. Li also met National Assembly Speaker Kim Jin-pyo as part of his Asia tour, setting up the leadership exchanges in November. PRC Ambassador Xing Haiming’s comments after a forum hosted by the Korea Press Foundation and Chinese Embassy in December renewed Korean skepticism over the likelihood of any immediate “reciprocal” Xi visit.

In other China-ROK bilateral developments, the ninth repatriation of the remains of Chinese People’s Volunteers killed in the Korean War was completed on Sept. 14-17. A joint fishing committee meeting in Nov. 15-18 also agreed to cut fishing activities in exclusive economic zones. However, the summits in Southeast Asia that month indicated the relative weakness of China-ROK political and security ties amid escalating threats from Pyongyang, and rising anxieties over the economic partnership’s strategic implications.

Xi-Kim Correspondence and Prospects for Resumption of China-North Korea Trade

Kim Jong Un and Xi Jinping enjoyed an active correspondence on the occasion of politically important events and anniversaries that emphasized close cooperation and common interests between the two leaders. Xi sent a message to Kim on the occasion of the 74th founding anniversary of the Workers’ Party of Korea (WPK) on Sept. 9. According to Rodong Sinmun, Xi’s message emphasized the “important consensus on planning the blueprint for the development of relations between the two parties and countries” and reiterated a willingness to work with North Korea to “maintain strategic communication, strengthen coordination and cooperation, and jointly uphold, consolidate, and develop China-DPRK relations.” Kim responded on Sept. 19 with a message that expressed confidence that the bilateral relationship, “established and consolidated in the struggle for socialism, would steadily develop on a new high stage.”

Kim sent another message to Xi on the 73rd anniversary of the PRC’s founding on Oct. 1, acknowledging China’s achievements and anticipating the significance of the 20th Party Congress. Xi Jinping responded on Oct. 13, in which he again emphasized the importance of “strategic communication” to boost “unity and cooperation” between the two countries. Kim sent a message to Xi upon the conclusion of the 20th Party Congress congratulating Xi on his leadership and pledging to shape a “more beautiful future” for relations between the two countries “so as to continue to powerfully propel the socialist cause in the two countries.” In his Nov. 22 response to Kim, Rodong Sinmun reported that Xi thanked Kim for his congratulatory message and reiterated the importance of bilateral cooperation in the face of “unprecedented” changes in the international situation and expressed his commitment to “intensifying the work to plan and guide the bilateral ties and defending, consolidating and developing them with credit.”

On Nov. 30, Kim Jong Un sent a message of condolence on the passing of former Chinese leader Jiang Zemin. Senior members of the WPK visited the Chinese embassy in Pyongyang to present a wreath in commemoration of Jiang’s passing. In addition to public correspondence between leaders, Rodong Sinmun reported the installation of a monument in honor of Kim II Sung erected at the Nan Jiao farm in Beijing, where Kim visited in 1975.

North Korean Aggression and Regional Security

Managing Pyongyang’s threat escalation has been a clear priority on President Yoon’s regional diplomatic agenda. North Korea has fired more than 70 ballistic missiles, 9 intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM) among them, in 2022, nearly tripling last year’s record of 25. Regional fears extend to conventional military threats and a looming seventh nuclear test. The testing of three short-range ballistic missiles and ICBM on Nov. 2-3 prompted an air raid alert for Ulleung Island for the first time since 2016 and amplified South Korean threat perceptions. North Korea’s Hwasong-17 “monster” ICBM was launched on Nov. 18, challenging Xi’s reaffirmations of regional security cooperation through separate summits with Biden and Yoon earlier that week.

Figure 3 An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is prepared for launch in this undated photo released on Nov. 19, 2022 by Korean Central News Agency. Photo: KCNA via Reuters

Throughout his Southeast Asia tour, Yoon sought to mobilize a firm response to DPRK threats while remaining open to dialogue by presenting his “audacious initiative” of economic aid to Pyongyang in return for denuclearization. Based on South Korea’s press release of their summit, Yoon told Xi “we expect China to play a more active and constructive role” as a UN Security Council (UNSC) permanent member and Asian neighbor. Xi affirmed China would support Seoul’s aid initiative “if North Korea responds favorably.” But the Chinese foreign ministry report on the summit’s outcomes made no explicit reference to North Korean security issues beyond broader regional “peace and stability.” The Xi-Yoon summit coincided with virtual talks between nuclear envoys on Nov. 15, where Liu Xiaoming reasserted Beijing’s position. As Liu told Korean counterpart Kim Gunn, “the parties concerned must squarely recognize the crux of the Peninsula issue and work to address each other’s concerns, especially the legitimate concerns of the DPRK, in a balanced manner…China will continue to play a constructive role in promoting the political settlement of the Peninsula issue.” In a Yonhap News interview a day later, South Korea’s Unification Minister Kwon Young-se identified “extended deterrence, sanctions and pressure” as the “means to bring the North to the denuclearization (dialogue) table.”

US and South Korean foreign and defense agencies affirmed such tools in a Sept. 16 joint statement pledging “any DPRK nuclear attack would be met with an overwhelming and decisive response.” Before meeting Xi, Yoon drew further reassurances through Nov. 13 talks with US President Joe Biden and their joint statement with Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio on a comprehensive trilateral partnership for the Indo-Pacific. In addition to supporting the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, the three leaders launched a trilateral dialogue on economic security and signaled unity against “economic coercion.” Such moves raised South Korean unease over China’s opposition to the expansion of US alliance cooperation to include economic-security linkages. In response to US Forces Korea plans to host a US Space Force regional command to address North Korean threats as part of Biden’s National Security Strategy, a Nov. 28 Korea Times editorial cautioned: “care must be taken to not cause backlash from China.” Against mounting regional calls for China to play a constructive role, China-ROK defense minister talks on Nov. 23 made no substantive progress on jointly managing DPRK missile and nuclear threats or restarting dialogue.

The failure of multiple UNSC sessions on North Korea this year to generate joint punitive action or statements of condemnation fueled South Korean frustration with Chinese and Russian constraints. Media commentators on Pyongyang’s “mounting nuclear threats” urged China to “do more,” expressing disappointment after the Nov. 15 Xi-Yoon summit produced no consensus on peninsula security priorities. Some outlets concluded, “Yoon’s trip strengthens US-Japan-ROK trilateral ties to deter DPRK provocations.” Other observers voiced ahead of the Nov. 14 Biden-Xi summit, that “South Korea does not want to be dragged into the China-US confrontation.” Chinese state media projected favorable images of their first in-person interaction, claiming, the “long-awaited scene between China and the US gives the world relief.” Pointing to “signs of thawing strained ties,” a Korea Times editorial argued, “We urge Xi to join efforts by South Korea, the US and Japan to discourage the North from pressing ahead with another nuclear test.” By December, heightened threat perceptions and UNSC inaction drove the coordinated imposition of Japanese, South Korean, and US sanctions reinforcing trilateral unity. Washington led the push for a UNSC presidential statement as DPRK testing activities continued.

North Korea Benefits from Open US-China Rift at the UN Security Council

The most direct impact of the changed geopolitical circumstances boosting China-DPRK cooperation has been that, in the context of North Korea’s increased frequency and range of its missile tests in 2022, the UNSC has been paralyzed due to major power rifts between the United States on one hand, and China and Russia on the other. These gaps only grew as the US again pressed for UNSC action in response to North Korean long-range missile tests in September-October. Against the backdrop of deepening major power rivalry and strengthened China-DPRK coordination, the UNSC debate remained paralyzed.

On Oct. 5, US Ambassador to the UN Linda Thomas-Greenfield called for unity in response to an intense series of eight ballistic missile launches in nine days, including the launch of a long-range missile that flew over Japan. She appealed to the UNSC to unanimously condemn DPRK provocations as in the past and stated that North Korea is “testing capabilities that can threaten every single UN Member State.” But Chinese Ambassador to the UN Geng Shuang defended North Korea by stating that the launches should not be viewed in isolation and are linked to US-ROK joint military exercises. Geng echoed North Korean arguments that “the denuclearization measures taken by the DPRK went unacknowledged, and the country’s legitimate and reasonable concerns have not been addressed” despite US invitations to Pyongyang to pursue renewed diplomatic dialogue. Instead of pressing for further sanctions, he pointed to a joint China-Russia resolution on North Korea advocating for humanitarian measures, easing of tensions and resumption of dialogue, and a political settlement of the Korean Peninsula issue. North Korea has become a beneficiary of geopolitical rivalries that have motivated China to act as a shield against punitive UNSC actions.

Figure 4 US United Nations Ambassador Linda Thomas-Greenfield addresses a UN Security Council meeting to discuss North Korea’s ballistic missile test on Wednesday, Oct. 5, 2022 at UN headquarters. Photo: AP Photo/Bebeto Matthews

The UNSC held a second round of debates on Nov. 4 over North Korea’s flurry of 13 missile launches. US frustrations with UNSC inaction in the face of Pyongyang’s escalation of missile testing was evident as Ambassador Thomas-Greenfield asserted that the UNSC’s credibility was at stake. But Geng pointed to US military exercises and statements that threatened to end the regime if Pyongyang were to use nuclear weapons as precipitating factors enflaming DPRK security concerns, instead arguing for a “dual track approach” of “maintaining peace and stability and achieving denuclearization on the peninsula and resolving issues through dialogue and consultation.” With China blocking UNSC condemnation of DPRK missile launches and giving a voice to perspectives North Korea had long-voiced in international forums, the United States had no choice but to pursue a multilateral statement of condemnation from like-minded countries at the UN.

Mixed China-Korea Economic Prospects

According to Chinese official reports, China-ROK trade grew by an annual 8.9% in January-July to $214.9 billion, and South Korean direct investment to China increased by 44.5%. By the end of the year, Korean customs data showed a 27% decline in exports to China in the Dec. 1-20 period and an 8.8% drop in overall exports compared to the same time last year, led by poor performance in chips and mobile devices. South Korea’s soaring accumulative trade deficit to $42.5 billion in January-November, twice the level in 1996 and more than three times that in 2008, heightened domestic fears of sustained recession. China’s slowdown and other global economic pressures drove adjustments in South Korea’s 2023 growth rate to between 1.5 and 2%, revising down earlier projections.

Meanwhile, Chinese media reported optimistically on bilateral economic cooperation spanning state, local, and nonstate levels, boosted by the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership that went into effect this year. Such multi-level exchanges met anticipations from the 26th Joint Economic and Trade Committee meeting on Nov. 24, led virtually by PRC Assistant Commerce Minister Li Fei and Korean counterpart Yun Seong-deok. That month featured the Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency’s export fair in Beijing and joint annual fairs engaging major provincial partners like Jiangsu and Shandong.

Chinese projections raise the critical importance of South Korea’s turn to China, its biggest trade partner since 2004, for domestic recovery and broader supply chain stability. At the 14th China-South Korea Media High-Level Dialogue in November, Vice President of the Academy of the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade Zhao Ping identified technological and industrial reform and the green economy as sources of optimism in emerging sectors. Dialogue participants included China’s Korea experts like Jilin University Vice Dean Zhang Huizhi, who in a Global Times interview also cited “a modification of South Korea’s previous foreign policy that seemed to be veering away from China in terms of economic integration.” After a Seoul economic forum on Nov. 22, a Global Times editorial favored “win-win” cooperation in line with business interests, arguing that “facing Washington’s decoupling push, South Korean companies have voted with their feet.” Another contributor on China-South Korea trade added a day later, “The biggest external disturbing factors for China-South Korea ties is always from Washington.” The Xi-Yoon summit appeared to catalyze China’s lifting of a six-year ban on Korean cultural contents since the THAAD dispute, as suggested by the resumption of online streaming of Korean contents in November. But China’s foreign ministry made clear on Nov. 23, “there has never been a so-called ban on ROK entertainment content on China’s part. China is open to cultural and people-to-people exchange with the ROK.”

Meanwhile, the Global Times reported in September that China-North Korea freight exchanges between Dandong and Sinuiju resumed after a five-month suspension due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The April 29 suspension coincided with North Korea’s first public admission of COVID-19’s entry, and the resumption of services followed North Korea’s declaration of victory over the virus in August.

South Korea’s Indo-Pacific Strategy and China’s Response

South Korea’s late December release of its Indo-Pacific strategy provided a snapshot of the impact of Seoul’s shifting policy toward China. Yoon’s Indo-Pacific strategy clearly aligns South Korea with the United States in support of a US-led international order defined by the rule of law and established normative frameworks. But the strategy also seeks to preserve a mutually beneficial economic partnership with China while pursuing a relationship based on mutual respect. Although the United States has identified China as a “pacing” challenge in an environment primarily but not exclusively identified by competition, South Korea has described China in its strategy as “a key partner for achieving prosperity and peace in the Indo-Pacific region.” More than a competitive relationship with China, South Korea seeks trust and reciprocity in a relationship with a better-behaved China.

While seeking to define a way forward for a positive China-ROK relationship based on mutual interests and mutual respect, Seoul’s alignment with Washington and expanded US-ROK cooperation on issues such as supply chain resiliency and broader Indo-Pacific strategy under the Yoon administration have begun to generate pressures on the China-ROK economic relationship. The balance between inclusion and exclusion on the economic and technology fronts has emerged as the most sensitive frontier of the relationship. While Korean firms are willing to invest in US-based semiconductor plants, they have no incentive to cut off semiconductor component trade in legacy products originated in China-located factories built with South Korean investment. SK Hynix quickly applied for and received a one-year exception to new US Department of Commerce licensing restrictions on exports of chip-manufacturing equipment to China released in October. A US regulatory approach that forecloses such trade imposes a significant economic cost for South Korean firms for which they will seek relief for foregone profits.

The Chinese initial response to the Yoon administration’s release of its Indo-Pacific strategy has been cautious. China has reiterated concerns that South Korea’s enmeshment in US-led economic security initiatives will disadvantage China and be costly for South Korea. In the Global Times, Dong Xiangrong of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences stated that “China is where South Korea’s real interests lie, and Seoul’s best strategy is to balance its ties between China and the United States.”

Conclusion: 2023 Outlook

Moving into 2023, the role of external parties and domestic politics remains a key concern amid US-China rivalry, North Korean provocations, and leadership transitions in Seoul and Beijing. At an Oct. 26 forum organized by South Korean media, Chinese Ambassador Xing Haiming identified the United States as “the biggest external challenge” to China-South Korea relations. He pointed to public opinion as the biggest internal challenge, citing the key role of “negative reporting on China by some Korean media outlets.” Responding to Chinese protests surrounding Beijing’s “zero-COVID” strategy, a Dec. 2 Korea Times editorial urged the Yoon government to better manage the economic risks from China, respond to public opinion, and address new virus cases.

The China-North Korea and China-South Korea relationships are both enablers and potential dampeners of tensions on the peninsula and in the region. These dynamics are playing out against the backdrop of US-China rivalry. The rise of major power rivalry has enhanced China-North Korea geopolitical alignment as Pyongyang uses its relationships with China and Russia as a shield against international punishment for its provocative long-range missile tests. But North Korea’s closer relationship with China does not appear to have enhanced China’s political influence in Pyongyang. It rather appears to have enabled North Korea to take advantage of international political paralysis for its own ends.

At the same time, South Korea under President Yoon has enhanced its alignment with the United States while seeking to enhance its international leadership role as a global pivotal state. By emphasizing inclusion and mutual benefit, Seoul seeks to enhance its leverage as a means by which to secure more even-handed treatment from China than Beijing has historically accorded to states on its periphery. For its part, China has tried to remind South Korea that its location next to China means that it shares both economic interdependence and security interdependence with China.

Sept. 9, 2022: Xi Jinping sends a message to Kim Jong Un on North Korea’s 74th founding anniversary.

Sept. 14-17, 2022: South Korea returns to China the remains of Chinese soldiers killed in the Korean War.

Sept. 15-17, 2022: China’s NPC Standing Committee head Li Zhanshu visits Seoul to meet President Yoon Suk Yeol and National Assembly Speaker Kim Jin-pyo.

Sept. 19, 2022: Kim Jong Un sends a reply letter to Xi Jinping.

Sept. 26, 2022: China’s foreign ministry confirms the resumption of Dandong-Sinuiju railroad freight operations after a five-month suspension due to COVID-19.

Sept. 28, 2022: DPRK Ambassador to China Ri Ryong Nam, President of the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries Lin Songtian, and other officials address an unveiling ceremony for a Kim Il Sung monument at Nan Jiao Farm in Beijing.

Sept. 29, 2022: Korea Enterprises Federation holds an annual meeting with Chinese Ambassador to South Korea Xing Haiming.

Oct. 1, 2022: Kim Jong Un sends a congratulatory message on China’s 73rd founding anniversary.

Oct. 5, 2022: China and Russia at a UN Security Council meeting block a US-led effort to condemn North Korea’s Oct. 4 missile launch across Japan.

Oct. 9, 2022: Chinese government and party representatives send floral baskets to the Worker’s Party of Korea marking the WPK’s 77th founding anniversary.

Oct. 13, 2022: Xi Jinping sends a reply message to Kim Jong Un.

Oct. 16, 2022: WPK sends a congratulatory message to Chinese counterparts on the opening of the 20th Party Congress.

Oct. 23, 2022: Kim Jong Un sends congratulatory message to Xi on the outcome of the 20th Party Congress.

Oct. 24, 2022: President Yoon congratulates Xi Jinping after the 20th Party Congress.

Oct. 26, 2022: South Korean Ambassador to China Chung Jae-ho and China’s Assistant Foreign Minister Wu Jianghao meet at South Korean National Day and Armed Forces Day Reception.

Oct. 30, 2022: President Xi and Premier Li Keqiang send separate condolence messages to President Yoon Suk Yeol and Prime Minister Han Duck-soo on the Oct. 29 crowd accident in Seoul.

Nov. 4, 2022: Ruling People Power Party leader Chung Jin-suk and Chinese Ambassador to South Korea Xing Haiming meet in Seoul.

Nov. 7, 2022: Main opposition Democratic Party leader Lee Jae-myung and Chinese Ambassador to South Korea Xing Haiming meet in Seoul.

Nov. 12, 2022: President Yoon and Premier Li meet at ASEAN summits in Cambodia.

Nov. 15, 2022: Presidents Xi and Yoon meet on the G20 summit sidelines in Bali.

Nov. 15, 2022: PRC and ROK nuclear envoys Liu Xiaoming and Kim Gunn hold telephone talks.

Nov. 15, 2022: South Korean Prosecutor General Lee One-seok meets Chinese Ambassador to South Korea Xing Haiming.

Nov. 15-18, 2022: China and South Korea hold a joint fishing committee meeting.

Nov. 22, 2022: China resumes online streaming of South Korean movie Hotel by the River.

Nov. 22, 2022: Xi Jinping sends a reply message to Kim Jong Un.

Nov. 23, 2022: PRC and ROK defense ministers Wei Fenghe and Lee Jong-sup meet at the ASEAN Defense Ministers’ Meeting-Plus in Cambodia.

Nov. 30, 2022: Kim Jong Un sends condolence message to President Xi over the death of former Chinese leader Jiang Zemin.

Dec. 1, 2022: South Korean Ambassador to China Chung Jae Ho visits a mourning altar in Beijing to pay respects to Jiang Zemin.

Dec. 1, 2022: China, South Korea, and Japan virtually hold the 23rd Tripartite Environment Ministers Meeting.

Dec. 2, 2022: President Yoon sends a condolence letter to Xi and visits a memorial altar at the Chinese Embassy in Seoul to pay respects to Jiang Zemin.

Dec. 12, 2022: PRC and ROK foreign ministers Wang Yi and Park Jin hold virtual talks.