Articles

Beijing and Seoul marked 30 years of diplomatic ties on Aug. 24 as South Korea transitioned to a new administration under President Yoon Suk Yeol, who took office in May. Although early high-level exchanges reaffirmed partnership, the two leaderships confront growing pressures from US-China competition, economic uncertainty, and public hostility. Domestic priorities in China in light of the 20th Party Congress and South Korea’s shift to conservative rule amplify these concerns. The impact of US-China rivalry on the China-South Korea relationship extends from security to economic coordination, including approaches to THAAD and global supply chains, and export competition, especially in semiconductors, challenges new Xi Jinping-Yoon economic agreements. Moreover, public hostility is strongest among South Korea’s younger generation, raising pessimistic prospects for future China-South Korea ties.

Despite mixed signals, false starts, and the continued absence of leader-level meetings marking the recovery of economic ties between China and North Korea, geopolitical developments have pushed the two countries closer together. Such engagement features mutual reinforcement of each other’s positions on issues of vital interest and solidarity in response to US policies.

Beijing and Seoul Mark 30 Years of Diplomatic Ties under New Korean Leadership

Chinese Vice President Wang Qishan’s visit to Seoul as the highest-ranking Chinese official to attend a South Korean president’s inauguration signaled China’s prioritization of relations with the new Yoon government. Talks between Yoon and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi on May 10 outlined the partnership’s goals and strategies, including strategic communication, economic and other functional fields of cooperation, cultural exchange, and multilateral and regional cooperation. These priorities were reaffirmed in virtual meetings between foreign ministers Wang Yi and Park Jin on May 16, and telephone talks between China’s top diplomat Yang Jiechi and South Korea’s National Security Advisor Kim Sung-han on June 2. The two leaderships commemorated the 30th anniversary of diplomatic ties on Aug. 24 by virtually linking their ceremonies in Beijing and Seoul, where Wang and Park exchanged messages from President Xi and President Yoon.

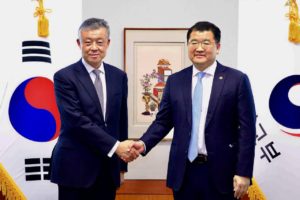

Figure 1 Foreign Minister Park Jin and Chinese Ambassador to Korea Xing Haiming celebrate the 30th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic ties between Korea and China in Seoul. Photo: Yonhap

Trust-building efforts characterized Wang Yi’s earliest proposals for advancing relations as “close neighbors and inseparable partners,” backing Yoon’s vision of bilateral ties “based on the spirit of mutual respect and cooperation.” Wang and Park held two face-to-face meetings during this period, on the G20 sidelines on July 7 and in Qingdao on Aug. 9. Defense ministers Wei Fenghe and Lee Jong-sup also resumed in-person defense ministerial talks at the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore on June 10, where they announced the expansion of bilateral military hotlines. In July, Chinese veterans affairs official Li Jingxian and South Korean Defense Ministry’s International Policy Director-General Kim Sang-jin agreed to hold a ceremony in September to return the remains of Chinese troops killed in the Korean War. China’s National Development and Reform Commission Minister He Lifeng and South Korea’s Finance Minister Choo Kyung-ho led the virtual 17th Meeting on Economic Cooperation on Aug. 27, where Wang and Park joined an online session reviewing policy proposals by the Committee for Future-Oriented Development of China-South Korea Relations. Created last year in light of the 30th anniversary, the committee called for “multilayered” dialogue including two-plus-two talks between foreign and defense ministries.

High-level exchanges in the early phase of the Xi-Yoon leadership era supported joint efforts to build trust through dialogue. Optimistic media projections of “pragmatic diplomacy” identified economic cooperation as “most important.” But active Xi-Yoon diplomacy also pointed to significant challenges, most notably US-China competition, economic uncertainty, and public hostility. As South Korea’s Ambassador to China Chung Jae-ho indicates, the 30-year relationship is impacted by the rising importance of traditional security issues involving third parties, namely North Korea and the United States. While debates over history triggered a downturn in South Korean perceptions of China starting in the 2000s, hostility toward China is strongest among the younger “MZ generation,” raising pessimistic prospects for future relations. In his first exchange with his new counterpart Park in May, Wang Yi encouraged the younger generation of both countries to drive the effort “to enhance friendship and reduce misunderstandings.” The “five-point commitment” Wang later presented in Qingdao included pledges of “independence regardless of external interference,” to uphold good neighborliness and friendship while accommodating each other’s concerns, to openness and “stable and unimpeded industrial and supply chains,” to “equality, mutual respect, and non-interference in each other’s internal affairs; and to multilateralism based on the UN Charter. Defense ministerial dialogues affirmed willingness on both sides to cooperate on North Korea and regional security, but they also revealed ongoing gaps in perception over the implications of the THAAD missile defense system for regional security.

The Yoon Administration Addresses US-China Rivalry

Yoon’s summit with US President Joe Biden on May 21, 11 days after taking office, produced a joint statement and press conference renewing South Korean views of a “precarious balance between Washington and Beijing.” In anticipation of Biden’s visit, optimists pointed to a “new era of alliance” cooperation extending “from security to economy and technology.” Local elections soon drove a struggle between Yoon’s People Power Party and main opposition Democratic Party over the risks of friction with China. Competing interpretations of the Moon administration’s “3 Noes,” Yoon’s participation in the NATO summit, and US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s Asia visit that included Taiwan intensified South Korea’s domestic polarization.

The THAAD controversy loomed over President Yoon’s May inauguration, when visiting Vice President Wang Qishan’s “discourteous and undiplomatic” remarks on the issue drew Korean public criticism. It resurfaced during the foreign ministerial talks in August, focusing on the previous Moon Jae-in administration’s “three noes” (no additional THAAD deployment, no participation in US-led missile defense, and no trilateral military alliance with the United States and Japan)—which the Yoon leadership treats as a non-binding agreement. Anticipating rising frictions with Beijing, media commentators urged the Yoon administration to say “No to Three Noes” and pursue “principled and proud diplomacy,” pointing to Beijing’s “double standard” on sovereignty. Others pushed South Korea to “keep close ties with China” through “pragmatic diplomacy” after Yoon became the first South Korean president to attend the NATO Summit in June, where he expressed solidarity with the Biden administration on universal values. Pelosi’s trip to Asia in August triggered similar calls that an upgraded US-South Korea alliance “should not hurt ties with China,” as ministers Wang and Park joined ASEAN meetings amid heightened tensions over her Taiwan visit. Calling Taiwan a “symbol of the US-China conflict,” conservative voices criticized the absence of a Yoon-Pelosi meeting in Seoul for “sending the wrong signal to both the US and China.”

Figure 2 South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol speaks in a meeting with US President Joe Biden, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken, US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida during a NATO summit in Madrid, Spain. Photo: Jonathan Ernst/Reuters

China Defends North Korea at the United Nations . . .

In response to North Korea’s repeated ballistic missile launches in early 2022 that included six intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) launches, the United States led a push for an additional UN sanctions resolution against North Korea for the first time since 2017. But that effort was blocked on May 26 by permanent Security Council members China and Russia, both of which vetoed the draft UN Security Council (UNSC) sanctions resolution that had won support from all other UNSC members. Although the resolution failed, the holding of the vote generated formal statements from several Security Council members including Chinese Ambassador to the UN Zhang Jun. Zhang justified China’s veto by stating that “the Council should play a positive and constructive role, and its actions should help de-escalate the situation and prevent it from deteriorating or even getting out of control.”

Subsequently, Zhang implied that a presidential statement from the UNSC might have won China’s support if the United States had not in Zhang’s view deliberately sought to create confrontation and “a showdown in the Council.” Zhang held up the Donald Trump administration’s pursuit of dialogue and negotiations as constructive while criticizing the Biden administration for failing to “reciprocate the DPRK’s positive initiatives in accordance with the action-for-action principle.” Zhang further argued that Security Council sanctions “are a means, not an end,” arguing for a political settlement rather than measures likely to escalate tension and have negative humanitarian consequences. Despite North Korea’s continuous rejection of US offers to return to dialogue, he concluded by calling on the US side to “take meaningful actions to respond to the legitimate and reasonable concerns of the DPRK, and create conditions for the de-escalation of the situation and the resumption of dialogue and negotiations.”

Figure 3 Chinese Special Representative on Korean Peninsula Affairs Liu Xiaoming visits Seoul. Photo: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China

In talks with Special Representative for Korean Peninsula Peace and Security Affairs Noh Kyu-duk in Seoul on May 3, China’s Special Representative of the Chinese Government on Korean Peninsula Affairs Liu Xiaoming expressed early hopes for diplomacy with North Korea under Yoon, who seeks a tougher approach to Pyongyang compared to his predecessor. During the four-day visit, Liu promoted such cooperation through separate meetings with top unification, foreign affairs, and national security officials of the Moon administration and incoming counterparts. Pyongyang test-fired a ballistic missile a day after Liu’s arrival, and the Yoon administration expressed its “deep regret” on May 26 when Beijing and Moscow blocked the proposed UNSC resolution. Citing North Korea’s rising military threat and China’s “contradictory” response, a Korea Herald editorial demanded Seoul to “strengthen not only the US alliance but also its solidarity with the liberal democratic camp” abroad. Liu and his new South Korean counterpart Kim Gunn affirmed their willingness to maintain dialogue through telephone exchanges on June 9 and July 26, as North Korean artillery drills underscored South Korea’s security concerns. But in the latest call, Liu reminded Kim that the peninsula stalemate persists because North Korea’s “steps toward denuclearization and its legitimate and reasonable concerns have not received the response they deserve.”

. . . While North Korea Shows Allegiance to China on Taiwan and the United States

North Korean Society for International Politics Study researcher Kim Hyo-Myong appeared to offer support for Chinese positions on regional affairs in a June 29 article featured by the Korea Central News Agency entitled “Asia-Pacific is Not North Atlantic.” This article took up NATO’s opposition to China as shown in its “new strategic concept,” arguing that NATO should stick to NATO business and keep itself from being used together with the “Quad” and “AUKUS” and forming a “trans-pacific encirclement ring aimed at containing and isolating China.” More specifically, Kim forecasted doom for South Korea for having “shaken dark hands with NATO, a root cause of disaster.”

Aligning with China’s position on Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan, a North Korean foreign ministry spokesperson responded to a journalist’s question on Aug. 3 that “we vehemently denounce any external force’s interference in the issue of Taiwan, and fully support the Chinese government’s just stand to resolutely defend the sovereignty of the country and territorial integrity.” Further reinforcing support of China’s position on Taiwan, the Central Committee of the Workers’ Party of Korea (WPK) sent a letter on Aug. 9 to its Chinese counterparts expressing solidarity with China’s response to “any reckless and vicious anti-China offensive by the US and its vassal forces…”

In addition, the North Korean foreign ministry took up public criticism of US congressional passage in August of the “Chips and Science Act” as evidence of “the sinister design of the US, and it has now provoked a backlash in China.” North Korea’s stepped-up support for Chinese and Russian positions in confrontation with the West illustrates the extent to which major power rivalry and political stalemate at the UN have generated strategic space for North Korea, even as it requires North Korea to be more vocal in its alignment with Chinese and Russian positions opposed to the United States and South Korea.

China-South Korea Economic Ties: Cooperation and Competition

The Aug. 27 China-South Korea Meeting on Economic Cooperation produced extensive agreements under the Xi-Yoon leadership, promoting: (1) supply chain cooperation through a new director-level consultative body, (2) public and private sector responses to global uncertainties, and (3) overseas projects in energy and other fields. The 10th round of follow-up FTA talks was held virtually on July 13, which focused on services and investment. Chinese Premier Li Keqiang and South Korean Prime Minister Han Duck-soo affirmed current priorities in their virtual address to a 30th anniversary business forum in Seoul on Aug. 24. Supporting multilateralism and principles of “openness” and “inclusion,” Li identified the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) as a driver of regional development and expressed hopes for concluding China-South Korea FTA talks. But economic competition and alternative multilateral initiatives are sources of strain.

China-South Korea trade reached $300 billion in 2021, almost a 50-fold growth since diplomatic normalization in 1992. South Korea represented 4.5% ($150.5 billion) of China’s total exports as its fourth biggest export destination. As South Korea’s biggest partner, China accounted for a quarter ($162.9 billion) of South Korean exports. South Korea’s overall trade deficit reached a record high of $10.3 billion between January and June of this year, renewing unease over export dependence on China. A Korea Herald editorial warned, “If a country depends too much on another country, particularly one with a contrasting ideology, it may be in a bind.” As the strongest driver of South Korean exports, growing from 3% to 40% of total exports to China between 2000 and 2020, semiconductors are a major source of Korean concern. The Korea Chamber of Commerce and Industry cautioned that Seoul should devise “plans to prevent China from weaponizing South Korea’s dependence on China,” especially given “China’s technological advancement and the tech rivalry between the US and China.” But such plans confront mixed responses to initiatives like the US-led “Chip 4 alliance” with South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan to manage supply chain disruptions. Addressing the National Assembly in August, Foreign Minister Park Jin and Industry Minister Lee Chang-yang countered fears over friction with China by refuting Chip 4’s competitive intentions.

Similar concerns over such competition emerged during Biden’s Asia visit in May, which featured a tour of a Samsung Electronics chip plant and the launching of the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF). Yoon called IPEF the “first step” to “work together to build a rule-based new order in the region” and assured South Korea’s participation as “a liberal democracy and a market economy system.” But the South Korean media already anticipated IPEF to be the “first major test for Yoon’s diplomacy” challenging Wang Yi’s proposals in Seoul on advancing the China-South Korea partnership. A Korea Times editorial cautioned that joining could prompt Chinese retaliation and regional instability, arguing, “IPEF membership should not sour Korea-China ties.” After the initiative’s official launching, others voiced the need for “pragmatic diplomacy…to protect national interests.” Domestic division prompted the Yoon administration to take early steps to emphasize that national interests were driving its decision. As Yoon told reporters on May 23, “if we exclude ourselves from the rule-setting process, it will cause a great deal of harm to the national interest.” In a press release ahead of Biden’s visit, the trade ministry identified supply chain resilience as a priority while also supporting economic ties with China through initiatives like RCEP and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

China’s COVID-19 Assistance to North Korea

Following its first public admission that COVID-19 cases had entered the country on May 12, North Korea announced a “severe national emergency” and redoubled the implementation of strict quarantine measures intended to contain the spread of the virus. Having reportedly rejected international offers for vaccine assistance including the Chinese-made Sinovac vaccine, the Korean Central News Agency provided official daily counts of 4.77 million cases and 74 deaths from May 12 to Aug. 10, at which time Kim Jong Un rolled back quarantine measures and declared victory over the virus. (A downside of the early declaration of victory is that any subsequent cases were characterized as the “flu” rather than a return of COVID-19 to North Korea.)

Following North Korea’s announcement that the virus had penetrated into the country, Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian stated that “China is ready to go all out to provide support and assistance to the DPRK in fighting the virus.” North Korea reportedly requested assistance a few days later, after which three Air Koryo flights were dispatched to Shenyang to transport medicines on May 17, the first flights between North Korea and China since January of 2020. A delegation of Chinese physicians also traveled to Pyongyang to play advisory roles to the North Korean government on how to manage the COVID-19 outbreak.

Figure 4 Kim Jong Un inspects a pharmacy in Pyongyang in a May 2022 photo released by KCNA. Photo: KCNA via AFP

Mixed Signals in China-North Korea Trade

Kim’s declaration of victory over the COVID-19 pandemic provided a basis upon which some observers speculated that the North might loosen its self-imposed isolation. Efforts to resume a spring trade fair in early May foundered on COVID-19 restrictions in China that forced it to go virtual with less than a dozen participating Chinese and North Korean companies on both sides, prior to North Korea’s admission that COVID-19 cases had reached the country. Both North Korea’s COVID-19 outbreak and its conclusion between May and August stimulated speculation that the leadership in Pyongyang might ease supply shortages by resuming freight train service with China following four months of suspension.

While China-North Korea trade recovered in the first four months of the year to over $100 million in April, North Korea’s COVID-19 outbreak pushed the May and June values back to around $20 million per month due to the resumption of quarantine restrictions. These reports included imports from China in July alone of over a million facemasks and 15,000 pairs of rubber gloves in response to the COVID-19 outbreak inside North Korea. Meanwhile, it appears that North Korea’s illicit trade in fuel with China has resumed despite both the COVID-19 quarantine and UNSC resolutions restricting the bilateral trade in oil and coal. It is hard to say whether the China-North Korea economic relationship has hit bottom, how quickly it might recover from the effects of COVID-19 quarantine, or to what extent the relationship has transitioned to an off-the-books exchange in critical areas, including as a way station for North Korean transfers of illicit earnings and laundering of cyber currencies.

Conclusion: Pessimism Clouds Beijing and Seoul’s 30th Anniversary

Commemorating 30 years of China-South Korea diplomatic ties, Xi Jinping stressed the importance of strengthening cooperation amid external structural shifts compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic. Similarly, Yoon seeks not just quantitative but also qualitative progress in relations with Beijing. But the 30th anniversary motivated critical reviews of the partnership, pointing to overall pessimism. China’s state media urged both sides to set a global example of “pragmatic diplomacy,” with economic cooperation as the foundation for managing external challenges. Although Chinese Ambassador Xing Haiming affirmed bilateral relations “have entered a more mature and stable stage,” he also expressed concerns over US-led competitive pressures extending to multilateral economic initiatives like IPEF and the smaller Chip 4 alliance. Perceptions of an escalating US-China “fight for hegemony” constrain South Korean hopes for the China-South Korea relationship under Xi and Yoon, including both leaderships’ trust-building efforts. As pessimists caution, the regional impact of such rivalry makes it increasingly “doubtful whether Seoul and Beijing can deepen their partnership further down the road.” Meanwhile, North Korea’s dependency on and alignment with China and Russia seem to have bought Kim Jong Un time and space to reconsolidate political control, but it is unclear whether North Korea’s external dependencies brings with them constraints on North Korea’s desire to continue military development, including a possible seventh nuclear test, at the expense of renewed diplomatic talks with South Korea and the United States.

July 3, 2021: Chinese veterans affairs official Li Jingxian and South Korean Defense Ministry’s international policy Director-General Kim Sang-jin meet in Xiamen and agree to hold a ceremony on September 15 to return the remains of Chinese troops killed in the Korean War.

May 3-6, 2022: Chinese Special Representative on Korean Peninsula Affairs Liu Xiaoming visits Seoul.

May 9, 2022: Moon Jae-in and Chinese Vice President Wang Qishen meet in Seoul.

May 10, 2022: Vice President Wang Qishen leads a Chinese delegation to Yoon’s presidential inauguration ceremony in Seoul.

May 15, 2022: South Korean media reports that North Korea has requested Chinese assistance on COVID-19.

May 16, 2022: Foreign Ministers Wang Yi and Park Jin hold virtual talks.

May 24, 2022: South Korean Joint Chiefs of Staff reports that two Chinese and four Russian warplanes entered the Korean Air Defense Identification Zone without notice.

May 26, 2022: China and Russia block a UN Security Council resolution a day after North Korean missile tests.

May 30, 2022: North Korean Vice Foreign Minister Pak Myong-ho expresses support for Xi Jinping’s new global security initiative.

June 2, 2022: Yang Jiechi and South Korean National Security Advisor Kim Sung-han hold telephone talks.

June 2, 2022: South Korean Vice Foreign Minister Cho Hyun-dong and Chinese Ambassador Xing Haiming meet in Seoul.

June 7, 2022: President Yoon Suk Yeol names Seoul National University Professor Chung Jae-ho South Korea’s Ambassador to China.

June 9, 2022: Chinese and South Korean nuclear envoys hold telephone talks.

June 10, 2022: Chinese and South Korean defense ministers meet on the sidelines of Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore.

June 11, 2022: South Korean Coast Guard seizes a Chinese boat for illegal fishing in South Korean waters.

June 12, 2022: An illegal Chinese immigrant is caught attempting to cross the Korean sea border by boat.

June 14, 2022: Seoul hosts the China-South Korea-Japan International Forum on Trilateral Cooperation.

June 22, 2022: Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi meets outgoing South Korean Ambassador Jang Ha-sung in Beijing.

July 7, 2022: Foreign ministers Wang Yi and Park Jin meet in Bali on the sidelines of the G20 meeting.

July 13, 2022: 10th round of China-South Korea FTA follow-up talks is held virtually.

July 20, 2022: South Korea beats China 3-0 in East Asian men’s football match.

July 20, 2022: Asiana Airlines resumes its Incheon-Beijing route in more than two years.

July 25, 2022: South Korean Trade Minister Ahn Duk-geun and Chinese Ambassador to South Korea Xing Haiming meetin Seoul.

July 26, 2022: Chinese and South Korean nuclear envoys Liu Xiaoming and Kim Gunn hold telephone talks.

July 28, 2022: Kim Jong Un expresses support for China-North Korea ties to commemorate the anniversary of the Korean War armistice.

Aug. 1, 2022: Chinese Assistant Foreign Minister Wu Jianghao and South Korean Ambassador to China Chung Jae-ho meet in Beijing.

Aug. 1, 2022: North Korea Defense Minister Ri Yong-gil sends a congratulatory message to Chinese counterpart Wei Fenghe marking the 95th anniversary of the PLA’s founding.

Aug. 3, 2022: North Korean Foreign Ministry through KCNA opposes Pelosi’s Taiwan visit.

Aug. 4, 2022: Chinese and South Korean Foreign Ministers Wang Yi and Park Jin attend ASEAN meetings.

Aug. 9, 2022: Chinese and South Korean foreign ministers meet in Qingdao.

Aug. 9, 2022: Workers’ Party of Korea sends a “solidarity letter” to the Chinese Communist Party denouncing Pelosi’s Taiwan visit.

Aug. 24, 2022: China and South Korea commemorate the 30th anniversary of diplomatic ties.

Aug. 24, 2022: South Korea’s Unification Minister Kwon Young-se and Chinese Ambassador Xing Haiming meet in Seoul.

Aug. 27, 2022: 17th China-South Korea Meeting on Economic Cooperation is held virtually.