Articles

This chapter was made possible through a grant from the Hindu American Foundation.

The Comparative Connections chapter on US-India relations covering the period September to December 2022 highlighted the challenge of getting past Cold-War era differences to fully capitalize on Indo-Pacific synergies. In the months between September and December of 2023, Cold War-era differences took center stage in the bilateral partnership. As a sliver of hope that the partnership would transform into a formal alliance emerged earlier in the year, these differences were spoilers. Differences in outlook brought to light the perennial challenges in the relationship and the need to get past the muscle memory of the Cold War for substantial engagement as defense and security allies. Despite these political and security differences, economic and technological cooperation largely expanded with increased cooperation in critical technologies and supply chain diversification initiatives. US industries broke new ground in expanding their footprint in India, and Indian conglomerates invested in the US, capitalizing on the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act and other industrial policies.

While technological advancements in the fourth industrial revolution and the rapidly evolving global macroeconomic landscape warrant new partnerships and alliances, political differences hold bilateral partnerships as prisoners of the past—such as the one between New Delhi and Washington.

The last four months suggest that the perennial challenge boils down to the clash of a values-led approach vs. an interest-led approach to foreign affairs. Washington’s vacillation regarding India’s, and of note, the Modi administration’s fit as a partner of shared values continues to hamper realizing the true potential of the “indispensable partnership.” India, for its part continues to conduct its statecraft using an interest-based and in a value-agnostic way—establishing partnerships with nations that serve its long-term economic, political, and technological interests. Despite both democracies working toward stabilizing relations with China, interests were aligned on broader strategic concerns vis-à-vis China and in keeping the Indo-Pacific a safe and secure region. That said, divergences in ideological values remained. This mismatch in values was profound in the domestic political sphere.

To the Polls

Both India and the US go to the polls in 2024. Adding a layer of complexity to the democratic exercise are flash-in-the-pan issues the parties use to boost their political capital. In India, several such issues have been blown out of proportion to whip up support for parties running for office. While the controversy surrounding the suggested name change of India to Bharat lost steam toward the end of the summer, a more significant development on the domestic front were state-level elections in five Indian states of Madhya Pradesh, Telangana, Chhattisgarh, Mizoram, and Rajasthan.

While analysts and pollsters predicted a thumping comeback for the opposition Congress party, it proved to be a shocker with the largest opposition party losing all but one race. Even though Congress surprised many with its victory in the central/southern state of Telangana, the bigger shock was its loss to the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in the Hindi heartland, squashing hopes of a revival in parliamentary elections scheduled for the summer of 2024. The BJP’s victory in the state-level elections will aid in implementing structural and macroeconomic reforms both at the federal and local level, assisting US businesses through stable governance.

In US politics, while India did not feature directly in the GOP primary debates, references to Biden administration’s policies toward China in the primary debates have an impact on US-India relations. The Biden administration’s first few years in office were largely an extension of the Trump administration’s hardline or hawkish position on China. However, over the last year, US-China relations have begun to slowly stabilize to the extent that the two are back to dialogue and regular interactions. Given that shared concerns over a rising China have transformed the bilateral US-India partnership, a lowering of US-China tensions could, consequently, dial back or at the least slow progress in US-India relations.

While most polls indicate a third term for the BJP, in the US the result is not predictable at this stage given the Republican primaries are not complete. Nonetheless, any extension of the Biden administration’s policies of the last year toward China will negate the urgency for increased cooperation between the US and India across security and defense spheres.

Furthermore, in an election year in India, it is commonplace for politicians to make bombastic statements, including on foreign policy. As the BJP celebrates the successful delivery of one of its electoral promises of building the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya, any violence or religious conflict that ensues as a result could affect the bilateral relationship.

The partnership cannot rely on political and security cooperation as its pillars. As has been the case over the last two decades and very much so over the last two years, the partnership is increasingly built on a dynamic technological and economic foundation.

After all, for all the divergences, the Modi administration’s steady march away from the socialist policies of the Nehruvian era is welcomed by both Washington and Wall Street. The penchant for the Modi administration to choose industrial policy for targeted efforts to support private enterprise to compete with Chinese state-owned enterprises is not viewed in the same light or as a “License Raj 2.0”. While it is a far cry from laissez-faire market economics, it is the most capitalist government in the nation’s history. As a matter of fact, former Finance Minister P. Chidambaram chided the incumbent finance chief Nirmala Sitharaman’s announced budget in as the most capitalist budget ever to have been presented to Parliament. What the former minister meant as a criticism is more of a badge of honor for the current administration and precisely what the doctor ordered to capitalize on the China+1 strategies of global conglomerates.

From License Raj 2.0 to Capitalism 1.0

In a sign of its pivot to capitalism, all outstanding US-India trade disputes were resolved with the final reduction in import tariffs on US poultry exports. It was not long ago when then President Trump characterized the Indian prime minister as “tariff king” for his administration’s high tariffs on a range of goods imported from the US. Fast forward to 2024, all trade disputes between the US and India have been resolved and India is absorbing several manufacturing and assembly units moving out of China.

In mid-December, Indian Ambassador to US Taranjit Singh Sandhu attended the event launching the first tranche of “Made in India” bicycles for Walmart. The Walmart story is suggestive of a larger shift. In 2018 the world’s largest retailers sourced over 80% of its goods from China. In 2020, that figure dropped to 60% while imports from India rose significantly. The company has a target of sourcing $10 billion worth of goods from India by 2027. Such initiatives are part of the supply chain diversification initiative coupled with increased cross-border investments increase economic interlinkages between the two economies. Indian companies are investing in the US, capitalizing on the Inflation Reduction Act. In October, Epsilon Materials announced a $650 million investment in North Carolina to battery materials for EV batteries.

Figure 1 Indian Ambassador Taranjit Singh Sandhu posing with a bicycle made in India in the United States. Photo: Sandhu TaranjitS

India successfully convened the G20 meeting. At the outset of the 2+2 ministerial meeting, Indian External Affairs Minister Subhramanyam Jaishankar thanked the US administration for its unwavering support. As the chapter covering May to September highlighted, New Delhi has a unique role to play in bridging the Western world and the Global South. Between September and December, New Delhi capitalized on every opportunity to voice the concerns of the Global South, while the US led the G7 nations in different theaters such as the Israel-Palestine and the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

President Biden, Prime Minister Modi, and other G20 leaders unveiled the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor as a direct competitor to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Adding to the existing I2U2 (Israel, India, United States and United Arab Emirates) partnership, the India-Middle East-Europe Economic corridor opened another channel for expanded cooperation among India’s largest trading partners (besides China) of the US and UAE. Moreover, these initiatives not only take on China’s BRI but also increase Washington’s engagement with the developing world.

In early September, the Indian Ministry of Defense (MoD) held the first virtual meeting of the India-US Defense Acceleration Ecosystem (INDUS-X) Senior Advisory Group with the US Department of Defense (DoD). While it has a long way to go toward increased joint production capabilities as New Delhi has with Moscow, it is a step in the right direction. Another strategic endeavor was the jet engine deal. In a surprising turn of events, the US Congress approved the joint production of jet engines with India in August 2023. India’s Hindustan Aeronautics Limited is slated to jointly produce jet engines with General Electric. These partnerships and developments in supply chain diversification initiatives would have been unfathomable a decade ago.

While economic and commercial engagement moved largely in the right direction, political, intelligence and security ties were a mixed bag.

An Old Friend Better than Two New Friends?

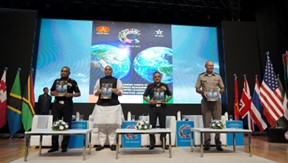

In late September, the US and Indian armies co-hosted events in New Delhi: the Indo-Pacific Armies Chiefs Conference (IPACC), the Indo-Pacific Armies Management Seminar (IPAMS), and the Senior Enlisted Leaders Forum (SELF) 2023 over three days. Two months later, Special Forces personnel from the Indian East Command joined personnel from the 1st Special Forces Group (SFG) of the US Special Forces for the 13th Vajra Prahar Joint Exercise in Umroi, Meghalaya in northeast India.

Figure 2 A three-day convergence of military leaders from the Indo-Pacific region, comprising IPACC, IPAMS, and SELF-2023, is jointly organized by the Indian Army and the US Army. Photo: IANS

The military of both nations are engaged in activities improving their interoperability and coordination. However, as the Ukraine crisis has shown, Cold War partnerships can spoil flourishing US-India ties. This time, it was a separatist movement with links to Pakistani intelligence that paralyzed the partnership for a few weeks.

In the first half of 2023, Indian missions in the US, UK, Australia and Canada came under vicious attacks by Sikh separatist groups that want to carve out Punjab and other northern states of India to create a nation called Khalistan. This violent separatist movement seeks to carve out a separate theocratic Sikh state in India, and has been tied to bombings, assassinations, kidnappings and the selective killing and massacres of civilians. This has resulted in nearly 22,000 deaths of Indian Sikhs and Hindus since the 1980s. The violence took on an international angle when Canada-based Khalistani militants blew up an Air India flight in 1985, killing all 329 people on board.

This violent movement lost steam in the late ‘80s after the assassination of Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi by her Sikh security guards. Over the last few decades, there have been isolated incidents, but the movement has found no resurgence in India but only in cities of the Five Eyes security group in the last few years. Over the last year, Indian consulates in the US, Canada, UK, and Australia were attacked by armed members of the separatist group. At the Indian Consulate General in San Francisco, Khalistan separatists set the neighboring building on fire — luckily no one was hurt. In the UK, the Indian flag was pulled down and in Australia, temples and consulate property were vandalized. While these events did not make the headlines in Western press, a drama unfolded, starting with Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s airplane having issues at the G20 in New Delhi which was followed by the Canadian leader accusing the Indian government of undertaking an assassination on Canadian soil. While it was reported later that a Five Eyes ally had shared intelligence of this alleged plot by Indian government agents and back-channel discussions were ongoing, the discussions did not prevent the crisis from getting media scrutiny, at least in the Western world. This issue flowed into US discourse when the US government accused India of plotting to assassinate dual Canadian-American citizen (labeled a terrorist in India). The lower district court of Manhattan charged Indian national Nikhil Gupta with murder for hire and conspiracy to commit to murder for hire. The indictment set back US-India relations, with Washington publicly accusing New Delhi of orchestrating a plot to assassinate a US citizen. The Indian government denied any involvement in the plot and instituted a committee to probe the accusations.

Figure 3 A Khalistan Referendum Event organized in Canada by the pro-khalistani group Sikhs for Justice (SFJ). Source: ANI file photo

Subsequently, there were several high-level visits to New Delhi, including the directors of the FBI and CIA. Several reports have indicated the separatist movements links to Pakistan’s intelligence agency the ISI. The US continuing to take a nonconfrontational approach with its former partner in the “war on terror” is turning out to be a thorn in the US-India bilateral partnership.

Weeks after this ordeal, the Oval Office rejected the Indian government’s invitation to be the chief guest of the Indian Republic Day celebrations on Jan. 26. Initially, the plan was Japan, Australia, and the US would attend the event, allowing the four nations of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (“Quad”) to stand together at the Republic Day celebrations. That did not pan out. While analysts such as Bruno Maçães predicted embarrassment and isolation for India without a chief guest, a product of its alleged activities abroad—India extended an invitation to French President Emmanuel Macron, who accepted the invitation on X, saying “thank you for your invitation, my dear friend. India, on your Republic Day, I’ll be here to celebrate with you!”

With these events, the US-India partnership was again held hostage to Henry Kissinger’s legacy—a foreign policy that pitted and prioritized relations with Pakistan and China vs India. New Delhi in response returned to its old friends, France and Russia.

Walking Down Memory Lane

In September 2023, India successfully convened the G20, its calls for including the Africa Union materialized and it hosted leaders from Sub-Saharan Africa for a dialogue led by the external affairs minister a month later. Media drew parallels to the assembly of leaders at the G20 with the non-alignment summit convened by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi—the only difference being the leaders that made the cover.

There is an old saying often used in Indian foreign policy discourse that goes, “an old friend is better than two new friends.” This has been quoted by the Indian prime minister himself speaking alongside Russian President Vladimir Putin as far back as 2016 to emphasize that the bilateral relationship is not limited to politics or trade but a friendship that lasts the test of time and geopolitical currents. Indian External Affairs Minister (EAM) S. Jaishankar, reminiscing over the supposed heydays of India-Soviet Union ties in 1962, while on a trip to Moscow shared on X an invitation letter to visit Moscow his father received while he was India’s foreign secretary. In an interview with ANI News, editor Smita Prakash asked Jaishankar about giving conflicting messages by posting from his Moscow trip as sort of a “mind game”; he responded that his mind games were working.

His trip to Russia came at the backdrop of the commotion surrounding the plot to assassinate a Khalistan separatist. A movement supported by Pakistan and indirectly by the US at the height of the Cold War was once again proving that the muscle memory of the Cold War was more formidable than imagined.

Figure 4 Invitation letter EAM S. Jaishankar’s father received to visit Moscow. Source: S. Jaishankur via X

While the US and its allies continue to engage Pakistan and refrain from adopting a zero-tolerance policy toward its support of separatist activity that threatens India’s national security, India has continued to emphasize its friendship with its Cold-War era partner.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Acting Deputy Secretary Victoria Nuland met Pakistani Chief of Army Staff Asim Munir weeks prior to the EAM’s trip to Moscow. These maneuvers are not healthy for bilateral US-India relations as they foster tit-for-tat diplomacy—a challenge to making any headway in bilateral relations. The US-India partnership remains caught in this vicious cycle.

Complicating matters, two major events were slowly unfolding in the background with potential large-scale and long-term implications for the bilateral partnership. One is the expansion of the BRICS group, once dismissed as a flash-in-the-pan initiative borne out of a banker’s analysis of emerging markets that has proven to be much more. On Jan. 1 the group expanded to include Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Iran, Ethiopia, and Egypt. The group, while not explicitly anti-Western, seeks increased representation in what they perceive as largely a multipolar world. As the group expands and gains broader significance, India’s role could further distance it from the Western nations and, of note, the US.

The second is the steps the Biden administration taken to stabilize ties with Beijing. It has reopened talks at the highest levels, including military-to-military dialogue and presidential-level meetings such as the one on the sidelines of the APEC meeting in San Francisco. Beijing has responded in proportion and eased visas for US travelers and called for engagement. Coupled with subnational diplomacy undertaken by governors such as Gavin Newsom of California and J.B. Pritsker of Illinois, and business leaders remaining enthusiastic about the Chinese market, Washington’s approach to Beijing could undercut increased cooperation with New Delhi.

India, while not as overt and forward-leaning as Washington, has, for its part, reopened dialogue with China, at least at the track-two level. A delegation from Fudan university visited a think tank in New Delhi for a dialogue and shortly after another delegation of senior-level diplomats made a trip out to the ideological brains of the BJP, the Rastriya Swayam Sevak Sangh’s Smruti Mandir. In a surprising turn of events, the Chinese nationalist tabloid Global Times ran an article praising the Modi administration’s suggested name change to Bharat. Nonetheless, between Washington and New Delhi, only one (New Delhi) has lost men and according to some sources, territory, to China making stabilizing or dialing back relations much harder and unlikely. Furthermore, engagement between Delhi and Beijing has so far been limited to track-two discussions and military-to-military dialogues to settle the border dispute. The Wuhan and Mammallapuram Xi-Modi summit in 2019, was the last leader-level dialogue between India and China. Post Doklam and Galwan valley clashes, there have been no high-level state visits nor dialogues between the two nations. The same cannot said of the United States. From subnational to track-two dialogues, the US has taken every measure to stabilize relations with China.

From New Delhi’s standpoint, the US has therefore not been a reliable partner vis-a-vis China and Pakistan. However, from Washington’s standpoint, New Delhi was not upholding the supposed shared values and not acting like a reliable partner by engaging Russia.

Despite domestic politics taking center stage due to elections in 2024, cooperation in the economic and technological sphere will continue to be lead as political and security cooperation between the US and India appears to lag. Furthermore, with new multilateral platforms, the divergence in understanding of the state of the world, i.e. multipolarity vs bipolarity, will limit the understanding of each other’s strategic affairs.

Conclusion

Within the values-interest paradigm, values gain salience when aligned with interests, which could lead to foreign policy congruence. US-India cooperation in addressing the belligerence of China in the Indo-Pacific is one possibility. Categorizing Russia-India joint production of defense equipment as a betrayal of shared values misses the forest for the trees. Joint production of defense goods not only secures India’s borders but through exports of equipment such as the Brahmos supersonic missile to Indo-Pacific nations such as Philippines and possibly Vietnam and Indonesia, overall deterrence measures are strengthened in the wider Indo-Pacific region. As noted in previous chapters, the marked expansion of relations between US and India across spheres sits on the foundation of a perceived China threat. Any strategic decision that addresses the threat is a point of convergence.

Washington’s recent acts to stabilize relations with China and New Delhi’s interest in having dialogue with Beijing reveal cracks in that foundation. Widening the cracks are Washington’s lack of attention to separatist movements on Indian soil that Delhi considers a threat to its national security. These events undercut progress made on the political front, such as attempts at courting India and, on the other end, bringing the US into the Global South. These events reinforce the perception of the US as part of an elite club of Western nations in groups such as Five Eyes and the G7 while India continues to form and become part of new groups that represent the Global South.

Still, a combination of macroeconomic and geopolitical factors has influenced commercial, technological, and trade decisions. In 2024, a lot will rest on US-India cooperation in technological domains and supply chain diversification initiatives to sustain the upward momentum in relations.