Articles

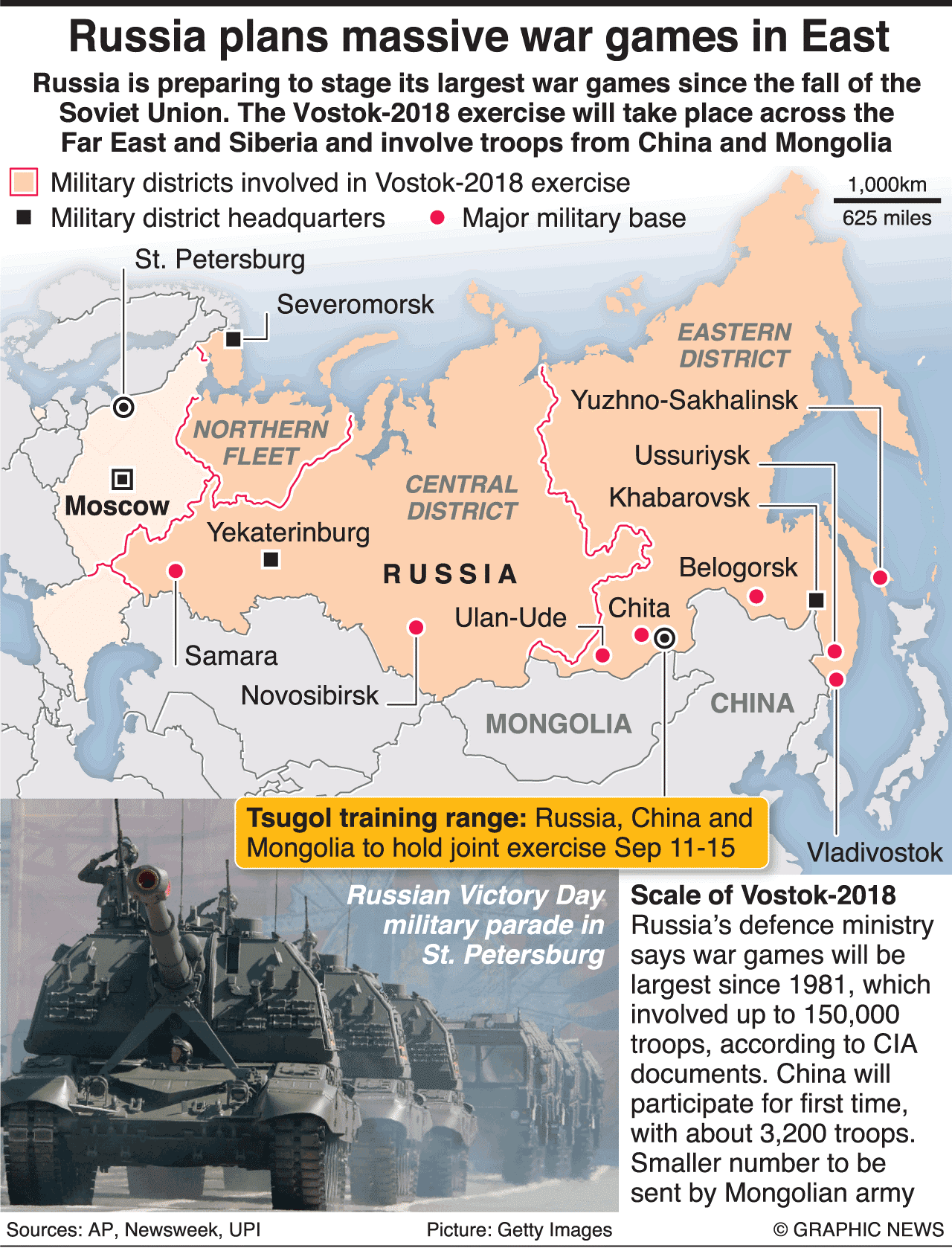

On Sept. 11, 2018, two separate but related events in Russia’s Far East underscored both the symbolic and substantive significance of the emerging entente between Russia and China. In Vladivostok, President Putin met Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping on the sidelines of Russia’s Eastern Economic Forum (EEF). On the same day, the Russian military kicked off its massive Vostok-2018 military exercise and was joined by People’s Liberation Army (PLA) troops. The EEF and Vostok took place at a time of heightened tension between the West and the two large powers in multiple areas, ranging from the US-China trade war, termination of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, Russia’s conflict with Ukraine (Kerch Strait on Nov. 25), the South China Sea (SCS), and Taiwan. Moscow and Beijing are increasingly moving toward a de facto alliance, albeit reluctantly. Welcome to the 21st century strategic triangle of reluctant players.

Between past and future

Sept. 11 was a big day for China-Russia relations: President Xi Jinping was the first Chinese president to attend the annual EEF since its debut in 2015 and Russia’s massive (300,000 troops) Vostok-2018 (East-2018, or Восток-2018) military exercise, for the first time, was joined by 3,200 People’s Liberation Army (PLA) troops. It is perhaps only a coincidence that 17 years earlier, the 9/11 attacks decisively reprioritized Bush 43’s foreign policy, shifting the focus from geopolitical competitors (China and Russia) to nonstate actors (terrorism).

The death of George H. W. Bush in December also marked a historical turning point. By the end of the Cold War, the 41st US president presided over a world in which both China and Russia were friendly to the US, even though they were still communist states. A quarter of a century later, the two large powers are officially defined as “strategic rivals” of the US for its “primacy.” Meanwhile, Moscow and Beijing are increasingly moving toward a de facto alliance, albeit reluctantly (see Yu Bin, “Between Past and Future,” Asia Policy, January 2018, p. 16), given the fact that they are so much apart politically, economically, and culturally.

EEF and Vladivostok summit

The Putin-Xi meeting in Vladivostok on Sept. 11 was the third meeting for the two leaders within four months. The summit, which took place the day prior to plenary sessions of the EEF, covered almost all areas of the bilateral relationship according to Putin: economic, social and humanitarian ties, and military and technical cooperation. Xi described the talks as “sincere, deep and fruitful.” Several documents were signed on regional economic cooperation, investment, banking, media, sports and academics, including a six-year program (2018-2024) for development of bilateral trade and economic and investment cooperation in Russia’s Far East. After the talks, the two heads of state joined a roundtable discussion with the heads of Russian and Chinese regions. More than 1,000 Chinese business people joined the EEF. Putin and Xi also visited the Ocean Russian Children’s Centre in Vladivostok, which took in 900 Chinese children who had suffered in a massive earthquake in the Sichuan Province 10 years earlier.

Photo: Chinese Foreign Ministry

Xi’s visit to Russia’s Far East was in the midst of “years of China-Russia local cooperation and exchange” (2018-2019). The goal is to inspire enthusiasm (Xi Jinping’s words) for local bilateral cooperation and exchanges primarily in the areas of economics and socio-cultural exchanges. For this, an “Intergovernmental Commission for Cooperation and Development of the Far East and Baikal Region of Russia and Northeast China” was created in February 2018 at the vice prime minister-level. The commission met twice in 2018 (February and August). China also set up a regional developmental fund of 100 billion yuan to help various Russian and Chinese regions in their economic cooperation. More than 100 activities are planned, including an investment conferences, trade fares, industry and agriculture exhibitions, seminars, art festivals, etc.

It remains to be seen how these actions and activities will provide any substantial stimuli to Russia’s economically under-performing Far Eastern region. Since the Soviet collapse, the region has lost more than 2 million people to the more prosperous Western (European) part of the country, despite subsidies and high profile investments from Moscow. Worse, many Moscow-sponsored large projects – Vladivostok airport, Vostochny Spaceport, Zvezda Shipyard – remain underutilized.

To reverse this trend, Russia officially initiated its “pivot” to Asia. The 2012 annual APEC meeting in Vladivostok is widely seen as the beginning of this eastward policy. Some went as far as to claim that “If Peter the Great were alive today, he would not have to re-find a new capital on the Pacific. He would simply pack up and move his court and his administration to an already-built city, Vladivostok.” Others point to the Vostok-2010 military exercise, which dispatched two divisions by train across Siberia and simulated tactical nuclear strikes to repel unnamed foreign aggression, as the starting point. Both were actually ahead of the US version of the Asia/Pacific “pivot” officially pronounced by then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in October 2011 in Foreign Policy.

It was the Ukraine and Crimean crises in early 2014 that pushed Moscow to look eastward, leading to the conclusion of a huge natural gas contract with China in May 2014, years after the two sides started to negotiate it. Moscow, however, appeared for quite some time unsure about what to do in the east: pivot to China, or broader Asia, including Japan, Korea, etc.; focus on geoeconomics or geopolitics or both? It looks as though Russia’s “Asia-pivot” origin myth (or confusion) continued in 2018 given the timing of the EEF and Vostok-2018 on the same day. The two high-profile efforts may, or may not, work together.

One of the key issues for Moscow is how to interface with China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which seemed, at least for a while, not only to bypass Russia’s Far East, but also all of Russia as its original thrusts were through the old Silk Road in Central Asia (Xi kicked off the BRI in Kazakhstan in 2013). It was under these circumstances that the EEF was launched in 2015. Its success may help Russia avoid the fate of “a hundred years (or possibly two hundred or three hundred) of geopolitical loneliness” [сто (двести? триста?) лет геополитического одиночества]. Xi’s appearance at the 2018 EEF in Vladivostok signaled more coordinated efforts by both sides for regional economic cooperation and security coordination.

Vostok-2018: size matters?

Vostok-2018 was said to have been the biggest exercise since the Soviet military exercise Zapad-81 (West-81) in 1981 involving 150,000 Soviet forces. This time, some 297,000 service members, 1,000 aircraft, helicopters and unmanned aerial vehicles, up to 36,000 pieces of equipment, 80 ships and support vessels were involved in the week-long drills (Sept. 11-17) across nine testing grounds, including four Aerospace Force and Air Defense grounds, and three seas – Sea of Japan, Bering Sea, and Okhotsk Sea – and Tsugol (Цугол) training ground, Zabaikalskiy Krai (Забайкальский край), bordering China and Mongolia.

These figures were disputed as “creative accounting,” “inflated,” or “utterly impossible” by Western analysts, citing past occurrences and logistic impossibilities of such a large-scale military operation. The real issue is the different degrees of readiness, mobilization, and movement for various forces and units. Active combat simulation may be practiced by a small number of troops. For Chinese observers, this is perfectly normal, and they would point out that at the peak of the Soviet power, only one Soviet motorized infantry division equipped with T-72 MBT was involved in the active combat simulation in Soviet Zapad-81.

At the technical level, the main objectives of the Vostok-2018 maneuvers were very similar to its predecessors: to check the military’s readiness to move troop over long distances, to coordinate among the individual services, and to perfect command and control procedures, according to the Russian Defense Ministry. Rapid mobilization of air and ground forces in Western Russia to the Far East were the main features of earlier Vostok exercises. This time, some Russian units (2nd Army of the Western Military District) covered up to 7,000 km and Northern Fleet ships sailed up to 4,000 miles, reported Russian Defense Minister Sergey Shoigu .

Photo: Graphicnews.com

For the first time, 3,200 Chinese troops (two integrated armored battalions) joined the exercises. Mongolia sent about 300 men. Despite its vast scale, most simulated ground combat actions for Vostok 2018 were conducted at Tsugol training ground in Zabaikalskiy Krai, located at the Chinese and Mongolian borders. “It is the first time as we hold such large-scale combat exercises jointly with foreign armed forces. We shall develop this military cooperation to enhance stability and security in the Eurasian area,” Defense Minister Shoigu commented after the drills.

The size of the Chinese forces for Vostok 2018 was just a fraction of the participating Russian troops. It was nonetheless the largest Chinese deployment ever sent to an overseas exercise. In Tsugol, however, the ratios of the Chinese and Russian personnel was greatly reduced to 1:8 (3,200:25,000). In terms of the number of ground equipment and aircraft, the ratios in Tsugol were, 1:12 (600:7,000) and 1:8.3 (30:250), respectively.

The two PLA armored battalions – one integrated heavy armored battalion (重型合成营) and an integrated medium-heavy battalion (中型合成营) with wheeled fighting vehicles – formed the bulk of the Chinese forces. Augmented by elements of helicopter, long-range artillery, Special Forces, and engineering units, the two PLA battalions were simulated as two brigades, which constituted the framework for an integrated army (军级架构). Both battalions belonged to the 78th Army of the PLA headquartered in Harbin, according to Chinese military experts.

In Tsugol, the PLA “army” was one of the six “armies” deployed in the field, all being represented by brigade-level forces (each of the five Russian “armies” was represented by a brigade of about 5,000 men). The PLA units were positioned as reserves at the heart of the “red” triangle of the 29th and 35th Armies at the front and the 36th Army in the rear (see map below). This enabled the PLA “army” to engage in initial defensive maneuvers in coordination with the “red” armies (29th and 35th) against two “invading” “blue” armies (2nd and 41st), as well as for the final counterattacks together with the “red” 36th Army and “red” paratroopers.

Despite the asymmetry in the forces involved in Tsugol (five Russian corps and one PLA corps), the Tsugol exercises were directed by a joint command consisting of staff members of Russia’s East Military District and PLA’s Northern Theater. PLA’s Joint Staff Department (联合参谋部), too, sent its staff to Tsugol. “The PLA is not a junior player (解放军不是配角),” claimed a Shanghai-based Chinese media outlet as it referred to the joint command and the centrality of the PLA deployment in the “red” formation.

Joint Command at Tsugol

PLA’s multi-colored fatigues vs. Russia’s green. Photo: Xinhua

Vostok-2018 operated in two phases: Phase 1 (Sept. 11-12) was for pre-drill planning and organization of forces, command and control, and logistics. Phase 2 (Sept. 13-17) were actual exercises, including conducting large-scale air strikes, Iskander-M strikes, cruise missile defense, defense, offense, flanking and raiding maneuvers. Outside Tsugol, Russian forces practiced defending against aerospace attacks, destroying surface action groups, and naval operations in the Sea of Okhotsk, Sea of Japan, and the Bering Sea (see map below).

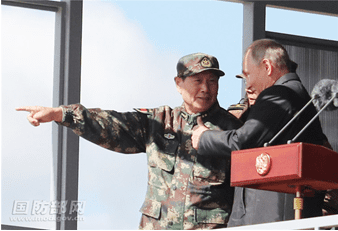

On Sept. 13, President Putin observed a parade of participating units and almost all the combat equipment. Defense Minister Wei Fenghe led a group of Chinese observers to Tsugol. Putin praised the troops in his speech after the parade and presented awards to 10 Russian, Chinese, and Mongolian military personnel who distinguished themselves during the maneuvers. “Very successful, very stimulating and very impressive” (非常成功,令人振奋、使人震撼), commented Gen. Shao Yuanming (邵元明) after the Tsugol exercises. Shao was PLA’s deputy chief of staff and co-director of the exercises. For him and many others, the size of Vostok-2018 was never a problem. It was the process that mattered.

Russian President Putin and Chinese Defense Minister Wei Fenghe in Tsugol. Photo: Guanchazhe wang

In search of oneself, and each other

For both sides, an important goal of Vostok-2018 was to assess the strength and weakness of their own units. PLA’s two integrated “brigades” in Tsugol are typical components of China’s 13 integrated armies (集团军) – an outcome of the three-year restructuring launched in November 2015 and modeled after the US military, particularly the more mobile and digitalized US “Stryker brigades.” Vostok exercises provide the PLA a timely opportunity to test the Chinese-version of the “Stryker brigade,” particularly in comparison with the more traditionally structured Russian motorized infantry, tank, artillery, engineer, and air-defense brigades.

Russia, too, had a keen interest in learning from the PLA’s conversion to more mobile, integrated, and flexible brigades. Although it started much later than Russia’s own military reforms which followed the 2008 five-day war with Georgia, the PLA apparently has had far broader and deeper reforms than has the Russian military. To be sure, the PLA’s equivalent “Stryker” units are not as advanced as US brigades, but this was what the Russians would be able to work with at a time of rising tension with the US. The Russians reportedly were particularly impressed by the PLA’s wheeled integrated battalion.

The PLA did not send its best hardware, such as the Type-99A MBTs, Type-04A Infantry fighting vehicles (IFVs), and Type-10 120 mm wheeled howitzer/mortar. Its MBT ZTZ99s in Tsugol were inferior to Russia’s T-72B3; the PLA’s Type-86 APCs were also inferior to Russia’s BMP-2s. PLA’s more digitalized field networks for communication, command and coordination, however, reportedly more than offset its hardware inferiority. Some Chinese military observers went as far as to note that the PLA’s digitized and integrated units had “overwhelming superiority” (拥有压倒性优势) over Russia’s motorized rifle and tank brigades.

What the PLA lacks is real combat experience; its last combat was 40 years ago with Vietnam. The Russians seem to have never stopped fighting: two lengthy Chechen wars (1994-96 and 1999-2000), a five-day war with Georgia (2008), the ongoing “phantom” war with Ukraine (since 2014), and an open intervention in Syria. For that, the post-Soviet Russian state has earned a reputation in China as the “fighting nation” (战斗民族). The PLA, therefore, had a lot more things to observe and to learn from the Russian counterparts in Tsugol.

Not everything was impressive in Tsugol. The Chinese side noticed that the Russian and Chinese airmen used only conventional aerial munitions. No guided bombs were dropped. To the surprise of some Chinese observers, the Russian military continued to use T-72B3, T-72BM, T-82BV, and even T-62 MBTs, which were the most advanced and most powerful MBT in the 1960s and 1970s. They continue to be used more in Russia’s eastern units than in the West, a clear indication of strategic priority for the Russian military. One military expert said that the overall quality of Vostok-2018 was actually not much different from Zapad-81 (West-81) despite some new elements such as T-72B3, Su-30SM, Su-34, etc. Its multiple rehearsals prior to the Sept. 13 live-ammunition drills were less realistic compared with China’s simulation in the Zhurihe training range.

Vostok: back to the past, and future

Vostok-2018 was a mirror of historical changes with multiple political, strategic, and technical implications for both Russia and China, as well as their external relations. In addition to being Russia’s largest exercise since the Soviet times and first-ever exercise to include Chinese participation, the Vostok series clearly means to transition from targeting China to partnership with the world’s second largest economy.

The Chinese side is well aware of the original mission of the Vostok series. The China factor was considerably watered down in the Vostok-2010 and 2014 drills. While the former targeted terrorism, the latter was a demonstration to the West—in the wake of the Ukraine and Crimea crises—that Russia continued to be able to control its eastern part.

In terms of joint exercises with China, Vostok-2018 represented a major departure from previous joint anti-terror exercises (mostly under the auspices of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization) to the conventional defense-offense operations against “illegal forces” (非法武装) of a hostile state or group of states. It therefore paralleled, if not matched, the December 2017 US National Security Strategy that identified Russia and China as “strategic rivals” and the main threat to the US, ahead of terrorism and “rogue states” (Iran, North Korea, etc.).

Both Russia and China denied that Vostok-2018 targeted any third party. Messages from Russia, however, were inconsistent at best. When asked whether China’s involvement meant Moscow and Beijing were moving toward an alliance, Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov simply said that the exercise showed that the two countries were cooperating in all areas. In remarks during the review of troops in Tsugol, however, President Putin stated that it was the duty of Russian military to “support our allies, if required” (если потребуется – … поддержать союзников).

At the extreme end of the alliance rhetoric, Russian analyst Vasily Kashin (Василий Кашин, senior research fellow at the Russian Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Far Eastern Studies) argued that Vostok-2018 pointed to an open declaration of a Russo-Chinese military alliance, a view that was not shared by other Russian pundits. Dmitri Trenin, director of the Carnegie Moscow Center and a former Soviet Army colonel, believed that the message Russia sent to the West regarding Vostok-2018 was that China was “a potential ally.” “China, by sending a PLA element to train with the Russians, is signaling that U.S. pressure is pushing it towards much closer military cooperation with Moscow.” Vostok-2018, therefore, was seen as an open-ended process of strategic communication with the US and its allies. In other words, nothing is final and nothing is impossible, and all depends on the specific circumstances in which Russia and China reciprocate with the West/US.

China’s decision to participate in the Vostok series was apparently made in late May 2018 in Beijing at the 20th strategic dialogue by the Russian and Chinese General Staff, which was co-chaired by Russian Armed Forces Col. General Sergei Rudskoy and Maj. Gen. Shao Yuanming, deputy chief of staff of the Joint Staff Department of China’s Central Military Commission. An agreement was reached to boost military cooperation in light of “thorny international and regional issues,” read a statement released by the Chinese Ministry of Defense immediately after the dialogue.

The “broad consensus” reached by the two militaries was against a backdrop of growing tension with the US and its allies around the world. Prior to this, Russia-US relations deteriorated as Washington expelled 60 Russian diplomats and closed the Russian Consulate in Seattle in the wake of alleged Russian use of a military-grade chemical substance in the UK. Moscow reciprocated by expelling 60 US diplomats from Russia and closed the US Consulate in St. Petersburg. For China, US initiated a trade war, which officially began March 22, 2018 and quickly spilled over to other, and certainly more sensitive, areas such as the South China Sea and Taiwan. Just six days before the Sino-Russian Strategic Dialogue in Beijing, the US withdrew China’s invitation to the 26th Rim of the Pacific Exercise. China’s SCS activities were cited as reasons for China’s dis-invitation. Meanwhile, the US steadily and significantly elevated relations with Taiwan. For many in China, the “pillars” of bilateral relations (economics, mil-mil, Taiwan, etc.) have been seriously weakened if not broken just a year and half into the Trump administration.

Given these developments, Chinese and Russian defense officials “confirmed their intent to increase the level of cooperation and undertake constructive steps for further renewal of strategic cooperation between the armed forces,” reported TASS shortly after the May Sino-Russian Strategic Dialogue in Beijing.

After the Tsugol parade, both Defense Minister Shoigu and Chinese counterpart Gen. Wei Fenghe confirmed that such exercises would become regular. It is unclear how regular and where such exercises will take place, nor is it clear if China will reciprocate by hosting a similar drill. Under normal circumstances, the next Vostok exercise would take place in 2022 according to the Russian military’s annual training cycle of rotating through the four main military districts (Eastern, Central, Southern and Western). It remains to be seen if the PLA will be invited to annual drills in other Russian military districts. Already, the PLA Navy has exercised with its Russian counterparts in the Mediterranean (May 2015) and the Baltic Sea (July 2017). The Russian Navy, too, has reciprocated with drills in waters adjacent to China:

| Year/Month | Exercise Area |

| 2012-4 | Yellow Sea |

| 2013-7 | Sear of Japan |

| 2014-5 | East China Sea |

| 2015-5 | Black Sea/Mediterranean |

| 2015-8 | Sea of Japan |

| 2016-9 | South China Sea |

| 2017-7 | Baltic Sea |

| 2017-9 | Sea of Japan/Sea of Okhotsk |

Conclusion: alignment, not alliance

In the December 2017 US National Security Strategy, China and Russia were listed – 30 times together – as “strategic rivals.” Even before this point, the two were cast in highly ideological, if not evil, shades in works such as Bobo Lo’s Axis of Convenience (2009) and Robert Sutter’s more recent Axis of Authoritarians (2018).

In the policy world, however, China and Russia were treated quite differently. While Russia remains an irritant, many believe the Russia-China partnership could be weakened by reaching out to Russia for the purpose of confronting a much stronger China. Vice President Mike Pence’s China speech on Oct. 4 at the Hudson Institute was seen by many as a de facto declaration of Cold War 2.0, this time with China. However, the US’ highly politicized and internalized “Russia problem” made it impossible for any realistic rapprochement with Russia. Given these policy trajectories and contradictions, Vostok-2018 provided more traction for the closer Russia-China strategic partnership in an increasingly unfriendly, complicated, and unpredictable world.

Although Vostok-2018 was a step toward more military cooperation, it was experimental in that both sides tried to adjust to the other’s capability and interests. Beyond Vostok, China and Russia remain largely independent players with similar interests. Many in Russia and China are still haunted by the highly ideological and binding alliance of the 1950s that turned into three decades of hostile “divorce” (1960-1989). The current partnership may be just right. The ultimate goal of Russian and Chinese foreign policy is to operate within the existing world order (WTO for China; and ABM and INF for Russia, to mention just a few vital international regimes) even if it continues to be dominated by the West. For this purpose, the China-Russia strategic partnership remains an adaptable, dynamic, and open-ended process through which both sides manage important bilateral, regional, and global affairs without the binding effect of a typical alliance.

Given these considerations, the messages coming out of Vostok-2018 were carefully calibrated, particularly by the Russian military. Considerable efforts were made to make preparations for and execution of the exercises transparent. NATO and other countries were briefed about the purpose, size, location, and participants of Vostok-2018, including that of the PLA. In Tsugol, 329 Russian and foreign media outlets were present, together with 87 observers from 59 countries.

The Chinese side, too, seemed not to over-stretch Vostok’s implications. Of the two major events on Sept. 11, President Xi chose to attend the Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok, while letting his defense minister interact with Vostok drills. Although Chinese media were saturated with stories of the exercises in Tsugol, most of the coverage focused on tactical aspects: to learn directly from Russia’s real combat experiences acquired from operations in Syria and Ukraine, and to test the effectiveness of the PLA’s reform and restructuring since 2016 for a more lethal, mobile, digitalized and integrated ground force. For both militaries, the practical side of Vostok seemed to be the priority.

That said, the partnership seems also to be about preparing, through the Vostok series, for a more volatile environment given the unpredictable Trump administration. If the US can de-link itself from the rest of the world, Beijing and Moscow cannot. This is not only because of their more complex neighborhoods and 21st century global economic interdependence, but also because of the burden of their historical interactions. In this regard, Vostok-2018 serves as a mirror to search for themselves, and each other, in the timeless and tireless fashion of great-power games.

Sept. 3, 2018: Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Igor Morgulov meets Chinese Ambassador Li Hui in Moscow.

Sept. 11-13, 2018: Russia hosts fourth Eastern Economic Forum (EEF) in Vladivostok. President Xi Jinping joins the forum and meets President Vladimir Putin separately. Both join a Russian-Chinese regional leaders’ dialogue on Sept. 12.

Sept. 11-17, 2018: Russia conducts Vostok-2018 military exercises, involving nearly 300,000 soldiers, 1,000 aircraft and 900 tanks and 3,200 troops from the PLA.

Sept. 18, 2018: President Putin meets Chinese Vice Premier Han Zheng in Moscow. Han co-chairs with Russian Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Kozak (Дмитрий Козак) the 15th Joint Energy Committee meeting.

Sept. 19, 2018: First meeting of Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) railway administration heads is held in Tashkent. The new mechanism was created at the SCO Qingdao Summit in June 2018.

Sept. 19, 2018: The 17th SCO Meeting of Senior Officials in Charge of Trade and Economic Cooperation is held in Dushanbe.

Sept. 20, 2018: The 16th Meeting of the SCO Prosecutors General is held in Dushanbe. Participants sign protocol of intent to consolidate efforts against extremism and terrorism as well as transnational crimes that serve as a source of funding for terrorism, including illegal drug trafficking and human trafficking.

Sept. 24, 2018: China and Russia join a foreign ministerial meeting in New York with their French, British, German, Iranian, and EU counterparts.

Sept. 25, 2018: Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov meets Foreign Minister Wang Yi on the sidelines of the 73rd UN General Assembly session in New York.

Oct. 8, 2018: Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Igor Morgulov meets Chinese Deputy Foreign Minister Kong Xuanyou in Moscow to discuss the Korean Peninsula.

Oct. 11-12, 2018: The 17th SCO Prime Ministers Meeting in Dushanbe. Premier Li Keqiang and Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev meet on the sidelines.

Oct. 17, 2018: President Xi meets Chief of Staff of the Kremlin Presidential Executive Office Anton Vaino (Анто́н Ва́йно) in Beijing. Vaino also meets Director of the General Office of the Communist Party of China Ding Xuexiang.

Oct. 17, 2018: Seventh SCO Education Ministers Meeting is held in Astana. Participants discuss how to expand education exchanges of students and faculties, joint research projects, language studies, professional education and youth exchanges.

Oct. 17, 2018: President Putin meets Chinese Politburo Member Yang Jiechi in Sochi where Yang attends the 15th annual Valdai Discussion Club meeting.

Oct. 31, 2018: SCO Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure (RATS) holds its sixth conference titled “Combating terrorism: Cooperation without borders” in Tashkent.

Nov. 5-9, 2018: China hosts 39th session of military confidence building (MCB) and arms reduction (AR) in the border areas. Representatives from Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan join the conference. They approve the joint monitoring plan for 2019.

Nov. 7, 2018: Beijing hosts the 23rd China-Russia Prime Ministers Meeting. Twelve documents are signed covering regional cooperation, agriculture, health, aerospace and trade facilitation.

Nov. 15, 2018: President Putin and Premier Li Keqiang meet in Singapore on sidelines of annual (13th) East Asian Summit. Putin describes ties between the two countries as “privileged strategic partnership.”

Nov. 30, 2018: Presidents Putin and Xi meet in Buenos Aires on the sidelines of the G20 Summit. They also join an informal trilateral meeting with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and an informal meeting with other BRICS leaders and issue a communique.

Dec. 5, 2018: First Forum of the SCO Heads of Regions is held in Chelyabinsk, Russia.

Dec. 31, 2018: Chinese and Russian presidents and prime ministers exchange the New Year congratulating messages.