Articles

Perhaps more than any other time in their respective histories, the trajectories of China and Russia were separated by choices in national strategy. A year into Russia’s “special military operation” in Ukraine, the war bogged down into a stalemate. Meanwhile, China embarked upon a major peace offensive aimed at Europe and beyond. It was precisely during these abnormal times that the two strategic partners deepened and broadened relations as top Chinese leaders traveled to Moscow in the first few months of the year (China’s top diplomat Wang Yi, President Xi Jinping, and newly appointed Defense Minister Li Shangfu). Meanwhile, Beijing’s peace initiative became both promising and perilous as it reached out to warring sides and elsewhere (Europe and the Middle East). It remains to be seen how this new round of “Western civil war” (Samuel Huntington’s depiction of the 1648-1991 period in his provocative “The Clash of Civilizations?” treatise) could be lessened by a non-Western power, particularly after drone attacks on the Kremlin in early May.

Wang Yi’s Trip to Moscow: via Europe

On the eve of the anniversary of the Ukraine conflict, finding a way out became the top priority of China’s diplomacy. From Feb. 14-22, Wang Yi, newly appointed director of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Office of the Foreign Affairs Commission, traveled to France, Italy, Hungary, and Munich where he joined the 59th Munich Security Conference (MSC). Moscow was Wang’s last stop. In meetings with three European leaders (French President Macron, Italian President Mattarella, and Hungarian PM Orban), Wang held “in-depth” exchanges regarding the Ukraine conflict.

In Munich, Wang delivered a keynote speech titled “Build A Safer World,” which reiterated many of China’s previous stances regarding the Ukraine conflict. “China is not a directly involved party, did not choose to be a bystander or add fuel to the fire, still less exploit the crisis,” said China’s top diplomat. Wang also chose the moment to reveal that China would soon release a position paper on political solutions to the Ukraine crisis. In Munich, Wang also met with Ukraine Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba at the latter’s request on the MSC sidelines. “China does not want to see the crisis being prolonged and escalated,” Wang told Kuleba who was briefed on key elements of China’s peace plan.

Wang’s European itinerary had at least two purposes. The first was to seek European support for a peaceful settlement to the Ukraine crisis. China believed that Europeans were hardest hit by the war, though they went along with the US. Their position was crucial for the formal launch of China’s peace proposal at the one-year anniversary of the invasion. Not all European countries were receptive to China’s views. France, Italy, and Hungary, however, were considered more “independent” from Washington, according to Chinese calculations. Munich was also a convenient place to interact with Ukrainian diplomats.

Wang’s second goal in Europe was to stabilize Euro-China relations, which had been bumpy in the past few years even before the Ukraine crisis thanks to Biden’s alliance-building effort. In the last part of his MSC speech, Wang defined a multilateral world in which Europe and China were “two large powers, two large markets, and two civilizations.” And they should choose dialogue/cooperation over hostile camps, and peace/stability over a new cold war.

During his two-day stay in Moscow (Feb. 21-22), Wang held talks with Russian counterpart Nikolai Patrushev, as well as Foreign Minister Lavrov and President Putin. In the Kremlin, Wang reminded his host that his visit was urged (“as soon as possible”) by the Russian president during his video talks with President Xi at the end of 2022.

Putin started with his “best wishes to comrade Xi Jinping,” a Soviet-style reference for intra-communist exchanges. He also spoke highly of relations with China in economic, diplomatic, and security areas, stressing that the two countries provided an important “stabilizing” effect for the “complicated” international relations. The Russian president then reminded Wang of “an earlier agreement” for President Xi’s state visit to Russia and hoped that Xi would come once his domestic agenda (annual parliamentary meeting in March) was done.

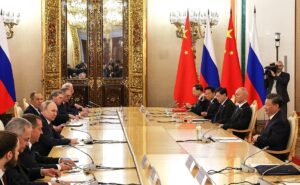

Figure 1 Russia President Vladimir Putin meeting China Foreign Minister Wang Yi at the Kremlin in Moscow, Russia on Feb. 22, 2023. Photo: TASS

Wang did not directly respond to Putin’s reminder of Xi’s next visit to Moscow, according to the readouts of both governments. Instead, Wang had “an in-depth exchange of views on the Ukraine issue” with Putin, during which the top Chinese diplomat stressed a “dialectic” discourse of turning crisis into opportunities. “Although the crisis constantly makes itself felt, crises offer opportunities, and opportunities may turn into crises,” remarked Wang. Regardless of the specifics of the Wang-Putin meeting, the Chinese envoy “appreciated Russia’s reaffirmation of its readiness to solve problems through dialogue and negotiations.”

Wang left Moscow without an official joint statement with his Russian host. His visit, nonetheless, kicked off a series of efforts by China to promote dialogue and peace around the world. On Feb. 21, when Wang arrived in Moscow, China released a “Global Security Initiative Concept Paper,” calling for a “common, comprehensive, cooperative and sustainable security,” which respects “the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all countries.”

Two days after Wang returned to China from Russia, China unveiled its formal “Position Paper on the Political Settlement of the Ukraine Crisis.” In addition to the major principles China articulated in the past year (#1-6), the 12-point paper specifies several relevant issues such as nuclear power plant security (#7), preventing the use of nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons (#8), grain exports (#9), stopping unilateral sanctions (#10), postwar reconstruction (#12), etc.

The immediate reaction to Beijing’s 12-point peace proposal indicated a wide spectrum of opinions: from Washington’s outright rejection, European skepticism, and UN endorsement (Secretary General Guterres’ office considered China’s plan an “important contribution”), to Russia’s “polite but tepid” reaction. Russian Presidential Spokesman Dmitry Peskov said the Kremlin would study China’s plan “with great attention…and its details should be a subject matter of thorough analysis.” Meanwhile, “the special military operation continues. We are moving towards achieving the goals that were set,” added Peskov. Kyiv did not reject it as President Zelenskyy saw “some merit in the Chinese peace plan,” and wished to meet with President Xi. Still, he stressed that unless China’s plan included a proposal for the withdrawal of Russian troops from Ukraine’s territory, it would be unachievable.

While Wang Yi was traveling through Europe, more advanced and heavy NATO weapons were pouring into Ukraine, including powerful German Leopard 2 tanks, US Patriot batteries, etc. At the MSC, Vice President Kamala Harris pledged to support Ukraine “for as long as it takes.” Shortly before Wang Yi got to Moscow, President Biden made a surprise visit to Kyiv, his first trip to the country since the war begin. In the Ukrainian capital, Biden announced a half-billion dollars in new military assistance, which was quickly followed by $1.25 billion in economic assistance to Ukraine by US Treasury Secretary Yellen. The stage was being set for the much- discussed Ukrainian counteroffensive, which was ready by the end of April.

“March Madness”: From Middle-eastern Mediation to Moscow Meeting

China is not directly involved in the Russia-Ukraine conflict. A year into the war, the mood among many Chinese observers was increasingly pessimistic for the near future of the conflict. Sr. Col. Zhou Bo (周波) was alarmed at the MSC where Western participants overwhelmingly supported Ukraine’s war effort and paid minimum attention to any alternative. In contrast, China’s public space was increasingly divided, with visible skepticism on China’s relations with Russia and the peace initiative, particularly in online chatrooms. Given these constraints, China’s peace initiative was almost impossible to achieve. The alternative to doing nothing, however, was worse if the Ukraine conflict widened and escalated. For many in China, it was inconceivable for any side to win a conflict between the world’s largest and most powerful military alliance (NATO) and perhaps the largest nuclear arsenal (Russia). Russia’s possible defeat, too, would be a strategic nightmare as China may well be the next target for NATO.

Beijing, therefore, continued its effort. In early March, newly appointed Foreign Minister Qin Gang met Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov in New Delhi on the sidelines of the G20 Foreign Ministers meeting. In addition to signing the 2023 Foreign Ministerial Exchange program, Qin went as far as to offer a “comprehensive overview“ of China’s position on the Ukraine issue. He also reminded Lavrov that “broad agreements” were reached during Wang Yi’s recent visit to Moscow. Lavrov reportedly appreciated China’s “objective, impartial and constructive role” and said that Russia was committed to dialogue and negotiations.

China’s peace initiative got an instant boost from an unlikely source on March 10 when Iran and Saudi Arabia surprised the world by announcing from Beijing that the two arch-rivals would restore diplomatic ties immediately. In a trilateral joint statement with China, the three sides reaffirmed the principles of sovereignty and noninterference in the internal affairs of states. The Saudi-Iranian rapprochement was followed by a series of conflict de-escalation, fence-mending efforts, and goodwill reach-out in the greater Middle East, including Egyptian-Turkish rapprochement (March 18), Syrian President Assad‘s visit to UAE (March 19), Syria-Saudi talks for reopening ties (March 23), Egyptian-Syrian talks to reopen ties (April 1), Saudi-Houthi ceasefire talks in Yemen (April 9), etc. All of this was not to isolate Israel. Shortly before the announcement of the Iran-Saudi deal, China’s special envoy to the Middle East Zhai Jun visited Israel for talks with Israeli Foreign Minister Eli Cohen and his colleagues.

Figure 2 Wang Yi, Director of the Office of the Foreign Affairs Commission of the CCP, presides over the closing meeting of talks between a Saudi delegation and an Iranian delegation in Beijing, March 10, 2023. Photo: Xinhua

China drew a direct line between such efforts and those for the Russia-Ukraine conflict, as “the only major power that befriends everybody thanks to its policy of non-alliance and non-interference,” remarked Sr. Col. Zhou regarding the Iran-Saudi case on the 20th anniversary of the US war in Iraq. China, meanwhile, had “strategic partnership relations with all 12 ME countries.” According to Wang Di (王镝, director of Asia-African Bureau of the Chinese Foreign Ministry), President Xi began this last round of ice-breaking diplomacy for intra-Arabic/Muslim peace during the first China-Arab States Summit in Riyadh. “Like in the Middle East, China is the only major power that can play a constructive role in Russo-Ukrainian war. All other major powers have already sided with Ukraine. Beijing is not allied with Moscow, and still friendly with Kyiv. China has Russia’s trust even though it has not provided any military support,” added Zhou Bo. “The situation is much more complicated in Ukraine…but there is no turning back,” said Zhou.

President Xi’s Moscow visit on March 20-22 was said to have three goals of promoting mutual understanding, cooperation, and peace. It was Xi’s ninth visit to Russia in 10 years as China’s president and his 41st gathering with President Putin. The two heads of state went to an informal meeting shortly after Xi’s arrival in the late afternoon that lasted until late evening, noted a Chinese source. The Ukraine crisis was the focus. “The more difficult the situation is, the more space should be left for peace; the more acute the contradictions are, the more we cannot give up efforts for dialogue,” Xi was quoted as saying according to China’s news release. “We have carefully studied your proposals…and we remain open to negotiations,” responded Putin before going into the closed-door session. The meeting apparently went well, during which Xi invited Putin to visit China for the 3rd Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation.

The second round of talks on the following day (March 21) lasted for three hours with a “meaningful and frank” small session and an expanded meeting with functionaries of various fields. Xi and Putin then co-chaired the signing of a dozen documents, including the “Joint Statement on Deepening the Russian-Chinese Comprehensive Partnership and Strategic Cooperation for a New Era” and “the Joint Statement on the Plan to Promote the Key Elements of Russian-Chinese Economic Cooperation until 2030.”

Figure 3 Russia-China talks in a restricted format. Photo: Mikhail Tereshenko/TASS

The long “strategic cooperation statement” (9,230 Chinese characters) began with a reiteration that the China-Russia relationship transcended “the kind of military-political alliance during the Cold War…and has the nature of no-alliance, no-confrontation and not targeting any third party.” It was a “strategic choice” made by China and Russia based on their respective national interests and “was not to be swayed by external forces.” The long document covered nine main areas of cooperation including foreign affairs, security/nuclear policies, economics, scientific/education, climate, regional issues (Korea, Middle East, Africa…), and societal exchanges. The last part (#9) focuses on the Ukraine crisis. “The Russian side spoke positively of China’s objective and fair stance on the Ukraine issue,” said the statement. Russia also “reaffirmed its commitment to resuming the peace talks as soon as possible, which China appreciates.”

The joint statement for economic cooperation offered only broad strokes of the seven-year span (2023-2030). It did, however, prioritize improving the business climate (#1 clause), presumably on the Russian side, and key transportation infrastructure (#2), including rail/highway bridges, custom clearance procedures, cargo distribution centers, etc. They had been plagued by a surge in commodity exchange in the post-COVID era and because of Western sanctions. The statement also called for a “gradual increase” of the use of local currencies (RMB and ruble) in bilateral trade (#3). Rapid de-dollarization, which was already a fact of life for Russia, was not in the interest of China. With globalized outreach and huge foreign reserves in US dollars ($3.1839 trillion by the end of March 2023), Beijing favors a gradual process. Already, two-thirds of payments of bilateral trade were made in rubles and yuan. Another notable issue was the “industrial cooperation” (#7) for “standards matching” in various technical areas. Since the start of the Ukraine conflict, Chinese investors were rapidly filling the vacant manufacturing facilities abandoned by other foreign investors, particularly in the automobile and home appliance sectors.

The economic statement did not mention a $165 billion investment package of 80 “important and promising” bilateral projects (Putin’s words), which was discussed in the past year by the two governments. In a separate meeting on the morning of March 21, Russian PM Mikhail Mishustin, together with all seven deputy PMs and almost all ministers, discussed the large “investment portfolio” with President Xi. It was apparently part of the fine-tuning of the “seven-year” economic cooperation statement until 2030. Xi urged Mishustin to visit China “at any convenient time” so that he would get acquainted with China’s new prime minister, Li Qiang. After decades of slow growth in Russia’s vast Siberian and Pacific coast, China preferred a safer and steadier investment strategy for the longer term, which was the hidden theme of the economic cooperation statement.

“Moscow and Beijing have set far-reaching and ambitions goals for the future,” remarked Putin at the state dinner after two rounds of talks with his Chinese counterpart. “We have just signed an agreement on boosting bilateral relations that are entering a new era, and on developing economic cooperation until 2030,” added the Russian president.

The Ukraine-China Connection and Constraints

Shortly after the Xi-Putin meetings in Moscow, the Russian side disclosed that Putin and Xi “did not discuss Kyiv’s peace formula on the Ukrainian settlement during talks in Moscow.” Kyiv, however, was part of China’s mediation matrix. On March 6, China provided 200,000 euros ($220,000) to the IAEA for technical assistance to Ukraine for the safety and security of nuclear power plants and other peaceful nuclear facilities in Ukraine. The safety of these nuclear infrastructures was #7 point in China’s peace plan.

Four days before Xi’s Russia visit (March 16), Chinese FM Qin Gang talked over the phone to Ukraine counterpart Kuleba. Qin expressed concern that the crisis has dragged on and escalated and may even spiral out of control,” and hoped that Ukraine and Russia would keep alive the hope of dialogue and negotiation while not closing the door to a political settlement no matter how difficult and challenging it may be.

Kuleba “underscored” the importance of Zelenskyy’s peace formula. He also thanked China’s humanitarian assistance to Ukraine and noted that China’s position paper on the Ukraine crisis showed its sincerity. Additionally, Kuleba congratulated China’s success in mediating the Saudi-Iran peace six days before, according to a news release by the Chinese Foreign Ministry. The surprise turnaround of the decades—if not centuries—of intra-Muslim hostility as a result of Beijing’s proactive mediation did not escape Kyiv’s attention. For Beijing’s principled support of Ukraine sovereignty, Kuleba reciprocated with Ukraine’s commitment to the one-China principle and respect for China’s territorial integrity. This was quite a turnaround from nine months ago when Zelenskyy, in a video address to the Shangri-La Dialogue, called for international support for Taiwan before China attacks.

Returning from his Russia visit, President Xi Jinping told visiting French President Macron that he was willing to talk to Zelenskyy when the “conditions and time are right.” Twenty days later, Xi and Zelenskyy talked over the phone for a “long and meaningful” conversation (Zelenskyy’s words), the first since Russia’s “special military operation” began. Ukrainian sources described the hour-long talk as “an exchange of views” as the two presented their peace plans. They also “discussed a full range of topical issues of bilateral relations,” as well as “the ways of possible cooperation to establish a just and sustainable peace for Ukraine,” said Zelenskyy’s presidential website. “I believe that our conversation today will give a powerful impetus to the return, preservation and development of this dynamic at all levels,” added Zelenskyy. ’

On the same day, China announced that Li Hui, former Ambassador to Russia (2009-2019), would be dispatched as China’s special representative on Eurasian Affairs to Ukraine and other countries “to have in-depth communication with all parties on the political settlement of the Ukraine crisis.” Zelenskyy appointed Pavlo Riabikin as Ukraine’s Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to China.

Russia’s reaction to the Xi-Zelenskyy phone call was quite reserved. “We have taken note of China’s willingness to make efforts to launch a negotiation process,” said Russian Foreign Ministry Spokeswoman Maria Zakharova in a statement. She then tried to highlight the contrast between Moscow and Kyiv: “Our fundamental approaches are in line with the position paper that the Chinese Foreign Ministry released on Feb. 24,” while “the Kyiv regime has been rejecting all reasonable initiatives aimed at finding a political and diplomatic solution to the Ukrainian crisis,” said Zakharova. The Russian diplomat also reminded the audience that the head of the Ukraine Parliament Committee on International Affairs Alexander Merezhko recently dismissed claims that Taiwan is part of China. “We are ready to welcome anything that could help bring an end to the conflict in Ukraine,” remarked Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov the following day. The Xi-Zelenskyy talk, however, was “a sovereign matter…that pertains exclusively to their bilateral dialogue,” added Peskov. He also told TASS that Putin had no plans for any communications with Xi in the near future.

In contrast to Russia’s guarded tone for the Xi-Zelenskyy talk, the US reaction was quite positive. “We think that’s a good thing,” National Security Council spokesman John Kirby said, a sharp turnaround from his “we-would-not-describe-it-as-a-’peace mission” comment on Xi’s Moscow trip a month before. A week later, Secretary of State Antony Blinken weighed in by saying that “as a matter of principle, countries, particularly countries with significant influence like China, if they’re willing to play a positive role in trying to bring peace, that would be a good thing.” Both, nonetheless, urged China to move further to the Ukraine side. Thus, by the end of April, Beijing found itself not just between a rock and a hard place but being dragged by two powerful centrifugal forces in opposite directions.

And this was just the beginning.

China’s New Defense Minister in Moscow

While reaching out to Moscow’s opponents in Ukraine, Beijing tried to maintain normal relations with Moscow, particularly in mil-mil exchanges. On April 16-19, China’s newly appointed Defense Minister Li Shangfu (李尚福) visited Russia. “This is my first foreign visit after I became Defense Minister of China. I specifically chose Russia, so as to emphasize the special nature and strategic significance of our bilateral relations,” said Gen. Li in his meeting with President Putin shortly after he arrived in Moscow. As former director of the Equipment Development Department of the PLA and a PhD in aerospace engineering, Li‘s promotion indicated PLA’s prioritization of aerospace in its defense modernization program. And his three-day visit to Russia was a “packed and extensive program.”

Figure 4 Russia President Vladimir Putin’s meeting with China’s Defense Minister Li Shangfu in the Kremlin on April 16, 2023. Photo: RIA Novosti

Li’s visit was a follow-up to the Xi-Putin summit in March when the two heads of state also “discussed military-to-military cooperation,” according to Putin. They agreed to enhance communication and coordination of the two militaries. In his meeting with his Russian counterpart Shoigu, Li said that the visit “would take military cooperation between the two countries to ‘a new level.’” Li, however, also defined the mil-mil relationship as one that was “beyond the Cold War-era military and political alliances” between China and the Soviet Union, but “hinges on the principles of non-alignment and non-confrontation with third parties.” In his part, Shoigu emphasized that “[I]t’s crucial that our countries similarly assess the substance of the ongoing transformation of the global geopolitical landscape.” Interestingly, both Li and Shoigu were officially sanctioned by the US, and Li entered the “America’s Adversaries” list 40 months before Shoigu’s turn (Feb. 25, 2022) as a result of his role in acquiring Russia’s SU-35 fighter-bombers and S-400 SAM systems.

Neither Russia nor China disclosed specifics of the “new level” in their mil-mil exchanges during Li’s visit except a decision to have 20 senior PLA officers trained at Russia’s Military Academy of the General Staff in Moscow in the coming fall. China’s internet chatrooms speculated that the goal was to learn from Russia’s fresh lessons in its “special military operation” in Ukraine. Meanwhile, normal mil-mil programs went ahead, including the second joint naval drill with South Africa codenamed Mosi-2 on Feb. 22-27 and a joint naval drill with Iran code-named “Security Bond-2023,” in the Gulf of Oman on March 15-19.

Between War and Peace: from Leo Tolstoy to Mark Milley

The “normalcy” in Russia-China mil-mil exchanges occurred against the backdrop of an increasingly dangerous and unpredictable Ukraine conflict. Any peace process could be “strenuous,” warned Putin’s spokesman Peskov in February when China kicked off its mediation effort. By late April, Ukraine was on board after a “long and meaningful“ phone call between Xi and Zelenskyy. A week later (May 3), two drones attacked the Kremlin and Russia blamed Ukraine for the “assassination attempt on Putin.” Dmitry Medvedev, deputy chairman of Russia’s Security Council and Russia’s former president, went as far as to claim that the attack left Russia with no options other than the physical elimination of Zelenskyy “and his clique.” Both Ukraine and the US denied that they had anything to do with the attack. Meanwhile, China called for restraint by all sides. Its mediation effort, however, ceased to be an issue in the public domain if it has not evaporated entirely, at least for the time being.

Beijing, nonetheless, said it would “continue to work with the international community to play a constructive role for the political settlement of the Ukraine crisis.” Russia’s “proportionate response” to Kyiv’s “terror action,” however, would unfold after the annual V-D parade in Moscow on May 9, which would surely run into Ukraine’s long-anticipated spring counteroffensive.

Given the sudden turn of events, the only remaining optimist was Henry Kissinger who turns 100 years old in late May. “Now that China has entered the negotiation, it will come to a head, I think, by the end of the year,” predicted Kissinger in a recent interview with Ted Koppel. Between now and the year-end (if peace is indeed comes), more casualties will occur on both sides as the drone attacks on the Kremlin are pressure-cooking the already explosive situation.

Shortly before the drone attacks on the Kremlin, Gen. Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, offered perhaps the most sober assessment of the Ukraine crisis in the West. In a Foreign Affairs interview titled “How to Avoid a Great-Power War,” the top US soldier noted that the war in Ukraine “has essentially been stalemated.” The possibility of escalation, however, “is always there” even though “Russia does not want a war with NATO or the US and NATO and the US don’t want a war with Russia,” added Milley.

At the strategic level, Milley seemed to be distancing himself from Washington’s “hysterical China threat” (the interviewer’s phrase) and academia’s alarmists, such as Harvard’s Graham Allison (“Xi and Putin Have the Most Consequential Undeclared Alliance in the World,” Foreign Policy, March 23, 2023). Instead, Milley saw a de facto “tripolar world” and Washington should “make sure that Russia and China don’t form some sort of geostrategic, political, military alliance against the United States.”

With this sense of the different roles of the three huge powers being played out in the Ukraine crisis, Milley depicted a more independent China that does not want to side with either power in the conflict but is searching for a compromise. Ukraine President Zelenskyy, too, would agree with Milley that “China backing Russia in Ukraine would mean World War III,” as he claimed in February. As stated earlier in this piece, both Zelenskyy and Foreign Minister Kuleba understood the stake of the delicate peace across the Taiwan Strait whose further deterioration would leave Beijing with little choice but to throw its full weight behind Russia. This was what this author called some years ago a case of “reluctant allies.”

For Milley, great power war meant “horrific and unbelievable” destruction of human life, as he recalled his father’s experience in Iwo Jima, where 7,000 Marines died and 34,000 were wounded in 19 days. This, however, was overshadowed by the death of 40 million Soviets, 30 million Chinese, and 20 million Japanese. “[A]ll of us should recommit ourselves to preventing such a horrific catastrophe and try to resolve differences in means other than the use of the levels of violence that come with great-power war,” remarked Milley.

With that, Gen. Milley essentially echoed perhaps the greatest Russian novelist, Leo Tolstoy‘s famous line: “Who is right and who is wrong? No one! But if you are alive—live: tomorrow you’ll die…” in his timeless War and Peace (1865-69).

The Russian characters in Tolstoy’s narrative had little choice but to embrace Napoleon’s invasion of Russia. So did Milley’s father after Pearl Harbor. Statesmen of the 21st century, however, face dire choices, not necessarily between war and peace, but between a ceasefire and/or peace that nobody likes and a great-power war that would leave no winners.

Jan. 9, 2023: China’s newly appointed Foreign Minister Qin Gang holds a telephone talk with Russian counterpart Lavrov. Qin stresses that Chinese-Russian relations are based on the principles of non-allegiance, and non-confrontation, while not targeting any third party.

Jan. 12, 2023: Sino-Russian trade in 2022 increases by 29.3% to $190.8 billion, according to the Chinese customs office.

Feb. 2-3, 2023: Chinese Deputy Foreign Minister Ma Zhaoxu travels to Moscow for consultation with Russian counterparts Andrei Rudenko and Sergei Vershinin. They engage in “deep exchange” regarding global and regional issues. He also meets Russian FM Lavrov and the two call for “an early resumption of tourist trips between the two countries.”

Feb. 8, 2023: China’s Special Envoy on Afghan Affairs Yue Xiaoyong visits Russia and holds talks with Russian counterpart Zamir Kabulov in Moscow. They exchange in-depth views on the situation in Afghanistan, China-Russia coordination on Afghanistan, and other topics.

Feb. 19, 2023: China’s top diplomat Wang Yi meets Ukraine FM Kuleba at the latter’s request on the sidelines of the annual Munich Security Conference.

Feb. 20, 2023: Zhang Jun, China’s Permanent Representative to the UN, says that China supports Russia’s draft resolution submitted to the UN Security Council to investigate sabotage of the Nord Stream gas pipeline in September 2022. Russian submits a draft UNSC resolution to investigate the bombing following publication of Seymour Hersh‘s article on Feb. 8, 2023.

Feb. 20-27, 2023: Russia, China, and South Africa hold second joint naval drill, Mosi-2, in the Indian Ocean off the coast of South Africa. Three South African ships were joined by two Russian and three Chinese naval vessels. In November 2019, the three navies held the first joint naval exercises off Cape Town in waters of the Atlantic Ocean.

Feb. 21-22, 2023: Wang Yi, director of CCP’s Office of the Foreign Affairs Commission, visits Moscow for talks with Russian counterpart Nikolai Patrushev, head of Russia’s Security Council, Foreign Minister Lavrov, and President Putin.

Feb. 21, 2023: China releases a “Global Security Initiative Concept Paper,” calling for common, sustainable security and sovereignty for all.

Feb. 24, 2023: China issues a 12-point “Position Paper on the Political Settlement of the Ukraine Crisis.”

March 2, 2023: Foreign Minister Qin Gang meets Russian FM Lavrov on the sidelines of the G20 Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in New Delhi.

March 6, 2023: China announces the contribution of 200,000 euros to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) for technical assistance to Ukraine for the safety and security of nuclear power plants or other peaceful nuclear facilities in Ukraine.

March 15-19, 2023: China, Russia, and Iran hold a joint naval drill, code-named “Security Bond-2023,” in the Gulf of Oman. Two Russian ships and one Chinese vessel join the exercises.

March 16, 2023: Chinese FM Qin Gang has a phone call with Ukrainian FM Kuleba. Qin reportedly says that he hopes both sides would “keep alive the hope of dialogue and negotiation and will not close the door to a political settlement.”

March 31, 2023: China’s UN Ambassador Geng Shuang calls on all nuclear-weapon states to effectively reduce the risk of nuclear war. He also calls for the abolition of nuclear sharing arrangements, no deployment of nuclear weapons abroad by nuclear weapons states, and the withdrawal of nuclear weapons deployed aboard. Geng cites China’s peace proposal for the Ukraine conflict that opposing armed should not attack nuclear power plants or other peaceful nuclear facilities.

April 5-7, 2023: China and France agree to work for a peaceful solution to the Ukraine conflict during French President Macron’s three-day visit to China. “The two countries support any effort to foster a restoration of peace in Ukraine on the basis of international law and the goals and principles of the Charter of the United Nations,” reads Article 10 of their joint statement.

April 13, 2023: Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov meets with Chinese counterpart Qin Gang in Samarkand of Uzbekistan on the sidelines of the SCO annual foreign ministerial meeting. Lavrov describes relations with China as “robust and resilient.” Prior to this, the two foreign ministers joined Iranian and Pakistani for the 2nd informal meeting on Afghanistan. A joint statement is released calling for more international cooperation on the Afghan issue.

April 23, 2023: Vice FM Ma Zhaoxu holds a “diplomatic consultation” with Russian First Deputy FM Vladimir Gennadievich Titov in Beijing. They exchange views on the current international situation, the foreign policies of both countries and international and regional issues of mutual interest and concern.

April 26, 2023: Chinese FM Qin Gang chairs the fourth foreign ministerial meeting with five Central Asian counterparts in Xi’an, China and holds separate meetings with them. Qin tells them that China will firmly support Central Asian countries in safeguarding national sovereignty, independence, security, and territorial integrity, support the countries in independently choosing development paths in light of their national conditions, and oppose any external interference in the internal affairs of Central Asian countries. Qin also announces that the first China-Central Asia Summit will be held in Xi’an in May.

April 28, 2023: India chairs the annual SCO defense ministers’ meeting in New Delhi. The SCO defense chiefs pledge to boost strategic communication, focus on consensus, and expand SCO cooperation and jointly safeguard regional security and stability.