Articles

Unlike in 1914, the “guns of the August” in 2022 played out at the two ends of the Eurasian continent. In Europe, the war was grinding largely to a stagnant line of active skirmishes in eastern and southern Ukraine. In the east, rising tension in US-China relations regarding Taiwan led to an unprecedented demonstrative use of force around Taiwan. Alongside Moscow’s quick and strong support of China, Beijing carefully calibrated its strategic partnership with Russia with signals of symbolism and substance. Xi and Putin directly conversed only once (June 15). Bilateral trade and mil-mil ties, however, bounced back quickly thanks to, at least partially, the “Ukraine factor” and their respective delinking from the West. At the end of August, Mikhail Gorbachev’s death meant so much and yet so little for a world moving rapidly toward a “war with both Russia and China,” in the words of Henry Kissinger.

Xi-Putin Talk: Once in Four Months

Unlike their Western counterparts who gathered and communicated frequently in many multilateral and bilateral formats, Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping had only one direct dialogue in the May-August period. Their June 15 telephone conversation, however, revealed the quality, complexity, and direction of bilateral relations. Both stated that Russian-Chinese relations were at “an all-time high” and they reaffirmed their commitment to “consistently deepen the comprehensive partnership and strategic interaction in all areas,” though Xi pushed for “steady and long-term development of practical bilateral cooperation.”

The last time they talked was Feb. 25, when Putin briefed Xi about Russia’s “special military operation” in Ukraine, shortly after its start. This time, the war was the last item in their conversation. Instead, the two leaders started with issues of “practical cooperation” such as economics at a time of a “more complicated global economic situation.” Both pledged to expand cooperation in energy, transportation, finance, etc. Xi, for example, mentioned the Heihe-Blagoveshchensk cross-border highway bridge, which opened to traffic on June 10 after years of deliberation and delay.

To its east, the Tongjiang-Nizhneleninskoye railroad bridge was also ready to open in the second half of 2022. In addition to the new bridges, Russia’s energy exports to China reached an unprecedented high level for three consecutive months (May to July), in sharp contrast to the steady decline of Russia’s energy exports to Europe. In the first half of 2022, China-Russia trade increased 27.2% and much of the rise came from Russia’s exports to China (48.2%). Bilateral trade was expected to reach $200 billion in 2022, a sharp rise compared with the 2021 value of $140 billion. For security and reasons of cost-effectiveness, they handled a growing part of the bilateral economic intercourse through RMB and rubles.

Not everything was bright between Beijing and Moscow in the economic arena. In late June, Russian Vice Premier Yuri Borisov indicated that Russia would “decrease” its participation in the joint CR929 project, a long-range 280-seat widebody twinjet airliner. At the same time, however, China’s Ambassador to Moscow Zhang Hanhui revealed that China was “ready” to supply Russia with civilian aircraft components. In late August, a Chinese shipyard started to build for Russia the first nuclear-powered floating production unit (9,549 tons) with the RITM-200 reactor for the Arctic.

Global and foreign policy issues took up much of their conversation, as both leaders pledged to coordinate actions at the UN, Shanghai Cooperation Organization, BRICS, etc. Putin reiterated Russia’s depiction of Russia’s “overlapping” and “very close positions” in global affairs for “a truly multipolar and fair system of international relations.” Xi’s goal, however, seemed more moderate as he described China’s push for more “solidarity and cooperation among emerging market countries and developing nations” with the goal of an “international order and global governance towards a more just and reasonable direction.”

China’s press release provided more specifics on Russia’s positions. Putin was quoted as saying that Russia supported Xi’s April 21 Global Security Initiative, which overlaps considerably with Russia’s repeated calls for “indivisible security.” Putin was also cited for his opposition to “any force [interfering] with China’s internal affairs” (including Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and Taiwan). Putin briefed Xi at the end of their talks on Russia’s military operations in Ukraine. In his turn, Xi repeated China’s long-held policy of “independently assessing the situation on the basis of the historical context and the merits of the issue,” and said “all parties should push for a proper settlement of the Ukraine crisis in a responsible manner.” For this, the Kremlin press release considered China’s support for Russia’s special military actions as “legitimate” for “security challenges created by external forces.”

The sparsity of the top leaders’ interactions in May-August was offset by near-normal interactions at the functional levels of the two governments during this period. Lavrov and Wang Yi met in person several times (July 7, July 28-29, and Aug. 6) and via video at others. Other senior diplomats, too, frequently interacted on multilateral and bilateral forums for regional and global issues. Russia and China actively coordinated efforts in the SCO and BRICS with a greater sense of urgency to expand. Ten countries already intended to join the SCO by the end of August, among them Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Syria, United Arab Emirates. At a time of worsening relations with the West, deeper and more active engagement with the “rest” of the world were the consensus in Beijing and Moscow.

Military Cooperation: Business as Usual

According to the Kremlin website, military and defense issues were also part of the June 15 conversation, not mentioned in the Chinese press release. This discrepancy may reflect China’s official stance of principled neutrality in the Ukraine conflict. Its operationalization meant that China would walk a delicate line: continue its normal and ongoing mil-mil interactions with Russia but not provide Moscow with “material support” for military operations in Ukraine.

In his interview with TASS in early May, Chinese Ambassador to Moscow Zhang Hanhui—when questioned about changes in Sino-Russian military-technical cooperation (weapon sales, missile defense, etc.)—stated that China attached great importance to the issue and would deepen and broaden military-tech cooperation with Russia. Things looked routine in the next few months as the two militaries engaged in several “normal” exchanges:

- May 24: Russian and Chinese bombers conducted their 4th annual aerial patrols since 2019 over the East China Sea and the Sea of Japan. It was the first since the Ukraine conflict and coincided with President Biden’s Japan visit for the Quad summit.

- Aug. 13-27: China participated in the 8th annual International Army Games in Russia (main site) and 11 other countries, including Venezuela for the first time. More than 270 teams from 37 countries joined the games.

- Aug. 16: Chinese Defense Minister Wei Fenghe was invited to speak, via video, to the 10th Moscow International Security Conference. Wei also participated in the 2021 Moscow International Security Conference.

- Aug. 31-Sept. 7: The PLA joined the Vostok (East) 2022 strategic command and staff drills, together with troops from Belarus, Algeria, India, Tajikistan, and Mongolia. The exercises took place at 13 training grounds in Russia’s Eastern Military District. The PLA sent 2,000 servicemen, 300 pieces of equipment, 21 airplanes, and three warships.

As this “normalcy” of China-Russian mil-mil ties continued throughout May-August, so did China’s principled neutrality in the Ukraine war. Four days before the Xi-Putin talk in mid-June, Defense Minister Wei Fenghe told the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore that “China has never provided any material support to Russia with regard to the Ukrainian crisis.” The Ukraine conflict was “the last thing that China would want to see,” said Wei, adding that China supports dialogue between Russia and Ukraine and hopes that the United States and NATO would hold talks with Russia for the soonest ceasefire. In late June, the US side confirmed that no overt Chinese military and economic back of Moscow had been detected.

Russia’s “Taiwan Moment”

Between its principle and practical needs, China “threads the needle on Ukraine,” commented Andrew Nathan of Columbia University in Foreign Policy. What kept Moscow and Beijing apart, according to Nathan, was the fact that they had little interest in the other’s core interests: Taiwan and South China Sea (SCS) for China and Western threat in Eastern Europe for Russia.

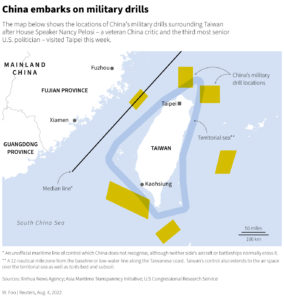

Nathan was both right and wrong. He was right because Europe and the western Pacific are separated by the huge Eurasian landmass. China, too, consistently argued that the Ukraine and Taiwan issues were totally different. Nathan was wrong, however, to ignore the fact that Washington was the common denominator for both Ukraine and Taiwan. Immediately after Pelosi’s controversial Taiwan visit on Aug. 2-3, the PLA staged a four-day massive military exercises around Taiwan, a dress rehearsal of a future blockade (see map below).

Figure 1 A map of Chinese military drills around Taiwan following House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taipei. Photo: Reuters

On Aug. 10, China published its third Taiwan White Paper (the first two were published in 1993 and 2000) with a much more assertive tone in curbing any internal and external forces for Taiwan’s separation from the mainland. On the following day (Aug. 11), US STRATCOM chief Navy Adm. Chas Richard revealed that the US was “furiously” writing a new nuclear deterrence theory that simultaneously faced Russia and China.

Despite its non-commitment to any crisis over Taiwan, Russia reacted swiftly and strongly to Pelosi’s visit. On the eve of the trip, Russian media blamed the US for “provoking China in ‘the most dangerous place on earth.’” Kremlin Spokesman Dmitry Peskov described the visit as “purely provocative.” He reiterated the point shortly after Pelosi landed in Taipei. Vladimir Dzhabarov, first deputy chairman of the International Committee of Russia’s Federation Council, or upper house of Parliament, went as far as to say that Russia may offer assistance to China if it was asked. Meanwhile, Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov stressed that he did not see any other “reason to create such an irritant literally out of nowhere.” As the Chinese kicked off the unprecedented military exercises around Taiwan on Aug. 4, Deputy Chairman of the Russian Security Council Dmitry Medvedev (Russian president in 2008-12 and prime minister in 2012-20) called Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan a “malicious provocation.” On Aug. 16, Putin weighed in. In his speech to the 10th Moscow Conference on International Security, Putin described Pelosi’s visit as “a thoroughly planned provocation” and “part of the purpose-oriented and deliberate US strategy designed to destabilize the situation and sow chaos in the region and the world.”

Behind Russia’s quick and supportive policy declarations was a much gloomier assessment of the rapidly deterioration of the delicate stability of cross-Strait/Pacific relations. Vasily Kashin, one of the most authoritative security analysts in Moscow’s prestigious Higher School of Economics, pointed out that Pelosi’s visit had led to “a new course on the Taiwan issue” by China with an emerging consensus that “the real possibilities for ‘peaceful reunification’ are narrowing.” This new course of the PRC was based on three assessments: “a simultaneous increase in separatist sentiments inside the island, an increase of American military assistance to the island, and an accelerated erosion of the one-China policy by the United States.” As a result, China’s “demonstrative military exercises are likely to develop into a real military intervention” if necessary.

Russia’ support for China was timely. In their meeting on Aug. 5 on the sidelines of an ASEAN conference in Phnom Penh, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi thanked his Russian counterpart Lavrov for “Russia’s immediate reiteration of firm support for the one-China principle and opposition to any act that infringes on China’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.” Wang attributed Russia’s actions to “the high-level strategic coordination between the two sides.”

Russia’s speedy reaction to Pelosi’s Taiwan visit was in sharp contrast to China’s carefully handled policy of neutrality on Ukraine. It also highlights the asymmetry of the Ukraine and Taiwan issue: Russia’s high sense of insecurity prior to its use of force in Ukraine and China’s patience and belief that time was on its side prior to the Pelosi visit. At least two additional factors contributed to Russia’s support regarding Taiwan. One was obvious: NATO’s eastward pivot was made official at the Madrid summit in late June. And for the first time in history, China was named in NATO’s official document as a challenger to West’s “interests, security, and values” that “seek[s] to undermine the rules-based international order.” Also for the first time, Indo-Pacific nations (Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and South Korea) were invited to attend. Already, various US-sponsored forums in the Indo-Pacific region were rapidly growing (the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, AUKUS, Blue Pacific, etc.) in the past two years.

Russia’s strategic playbook always included common sense: NATO’s newfound interest in the “China problem” would divert West’s attention away from the Ukraine conflict. In fact, Foreign Minister Lavrov had warned months before the Madrid summit that NATO’s “line of defense” was moving east. Even before Russia’s “special military operation” in Ukraine, he remarked that NATO’s attempt to influence the Indo-Pacific “a dangerous game.”

To Russia, with Arms?

Beijing reciprocated Russia’s public support with both words and deeds. In his Aug. 16 video speech to the 10th Moscow Conference on International Security, Defense Minister Wei Fenghe vowed to “to work with the militaries of various countries” for peace and security. Wei also called for “deepening defense cooperation” with other militaries this time, which was lacking in a similar speech at the same Moscow security forum a year before.

Wei did not directly mention Russia. At the International Military-Technical Forum “Army-2022” outside Moscow on Aug. 15-21, however, China’s military-defense institutions presented an unusually large and diverse range of products, including a total of 83 military and dual-use products of stealth fighters, AWACS, warships, mine-detecting sweepers, various radar devices, and military vehicles. Almost all the Chinese exhibits were said to have already been “equip by the Chinese military and/or been exported.”

Figure 2 Type-075 amphibious assault ship and Type-052D Destroyer models (Type-054A is not shown). Behind the naval vessel, models of various air defense weapons systems and drone models are on display. Photo: Guangchazhe Wang (Shanghai)

Figure 3 Various Chinese manned aircraft (left to right): J-10 fighter, L-15 trainer, Y-20 cargo plane (equipped with China’s WS-20 engines, not Russian D-30KP-2 engines), KJ-500 AWACS, JF-17 fighter (co-produced with Pakistan), and J-31 stealth fighter (likely to be adopted by the People’s Liberation Army Navy as a carrier-based fighter-bomber). Photo: Guangchazhe Wang (Shanghai)

On Aug. 20, Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu visited the Chinese exhibition area. He was accompanied and briefed by Maj. Gen. Wei Yanwei, China’s defense attaché in Russia, and representatives of the Equipment Development Department of the Central Military Commission. Shaoigu reportedly thanked the Chinese side for the “detailed briefing” (详细的介绍). Shoigu skipped the Chinese military product stand in the 2021 Moscow defense expo, but visited sites of Kazakhstan, India, Belarus, and Pakistan.

The lack of Russian attention to Chinese products in past expos may be natural because China was expected to buy, or learn about, Russian products and technologies. They therefore came mostly with cameras and notepads, remarked a Russian defense industry insider. Meanwhile, Russia was more interested in selling things to China. The 2022 Moscow expo seemed to be a watershed as the Chinese side was ready to market all the PLA’s major hardware to anyone including Russia.

Figure 4 Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu attends “Army-2022” in Moscow. Photo: Global Times (Beijing)

China did not develop its military equipment overnight. Its defense modernization has been underway for at least 30 years and continues today. Aside from its massive importation of Soviet arms during the 1949-59 Sino-Soviet “honeymoon,” China and the Soviet Union signed the first-ever military sale contract of 48 Su-27s on Nov. 1, 1990. This was followed by eight Kilo-class submarines (1993-94), four Sovremenny-class destroyers (1997-2002), S-300 SAM system (2001 & 2003), S-400 system (2015), 24 Su-35s (2015), etc. From 1992-2015, 80%, or $32 billion, of China’s arms imports came from Russia. Thereafter, arms transfers from Russia to China steadily declined due to the rapid development of China’s arms industry resulting first from learning from the Russian products and later its own R&D. On the eve of the Ukraine war, China had almost completely turned the table around from “buying everything (无物不买)” from Russia/Soviet Union to “almost nothing to buy” (无物可买), remarked a Chinese analyst. As a result, almost all the Chinese exhibits in the Moscow expo were indigenous Chinese products, though many components could be traced to Russian designs. Still, the Chinese arms industry maintained a low-key posture in Moscow’s annual military-tech expo until 2022.

The Ukraine war seems a turning point. China’s public space continued to be deeply divided in the summer regarding the ethics (who is to blame) of the war. More attention, however, was paid to the strategy-technology aspects of the war. Many were surprised by the seeming incompetence of the Russian military, its lack of precision-guided munitions, and slow adaptation to the battlefield reality. Many attributed this to the shortcomings of Russia’s military modernization focusing on its Battalion Tactical Group (BTG) as old-fashioned (over-emphasis on armor and lacking electronic surveillance and communication elements) without adequate infantry and logistical capabilities.

Russia’s shortage of drones was seen as a key factor, particularly the 2-in-1 long-range drones capable of both reconnaissance and attack missions. China’s WJ-700 (below), which was on display in Moscow this time, was said to be as good or even better than its US equivalent (MQ-9 Reaper).

Figure 5 China’s WJ-700 drone. Photo: Guangchazhe Wang (Shanghai)

It remains to be seen if Shoigu’s visit to the Chinese arms exhibition in Moscow would lead to any substance. The Russians were reportedly looking for Iranian drones and India’s Brahmos supersonic missiles (jointly developed with Russia), but have so far not purchased Chinese arms even as some Russian media urged Moscow to do so. Some in China toyed with the idea of reselling the four Russian Sovremenny-class destroyers (8,000 tons and newly refurbished) back to Russia, which would instantly elevate Russia’s naval power after major attritions of Russian naval surface vessels such as the sinking of the Moskva in April. However, various “internal obstacles,” including those in the Russian military and arms industry said to prevent Moscow from turning to Beijing for arms. Meanwhile, one should not rule out the importance of Russia’s “face.” For decades if not centuries, Russia was used to being China’s big brother with arms and advanced products going south. The reversal would be hard psychologically, argued a Chinese analyst. The biggest obstacle to acquiring Chinese arms was, therefore, Russia itself.

Arms transfer to Russia would mark a major change in China’s current posture of principled neutrality. Short of this step, China and Russia didn’t hesitate to add new elements to their mil-mil relations. The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), for example, was for the first time added to the Vostok-2022 exercises in August-September. Back to May, the joint China-Russia bomber patrol of the western Pacific included, for the first time, Chinese J-16 fighters to escort the bombers and the newly commissioned Y-20 tanker conducted midair refueling operations (below).

Figure 6 Two Chinese J-16 fighter jets conduct an escort mission for a Chinese H-6K bomber and a Russian Tu-95MS bomber during a regular China-Russia joint strategic patrol above the Sea of Japan, the East China Sea and the West Pacific on May 24. Photo: Global Times (Beijing)

Figure 7 A midair refueling of a Y-20 tanker conducted during a joint China-Russia bomber patrol. Photo: Global Times (Beijing)

Finally, China’s principled neutrality in the Ukraine war was, and perhaps should be, more precisely defined, argued Zhao Huasheng, one of the most prominent Russologists in China. China’s policy was not typical neutrality but one of “constructive involvement” (建设性介入), argued Zhao. While the former was passive, aloof, and rigid; the latter was flexible and constructive. A typical neutrality could be irresponsible regardless of right or wrong, said Zhao. China’s “constructive involvement,” by contrast, was based on the merits of the issue, and specific actions of the parties involved. In the case of the Ukraine war, China actually supported both parties: sovereignty for Ukraine and Russia’s security concerns. Neutrality would support neither. Taken together, China’s policy may not entirely support Russia, particularly in the ethical domain. It was, nonetheless, a rejection of US and NATO eastward expansion.

In China’s public/intellectual space, Zhao’s effort to clarify China’s policy toward the Ukraine conflict shed light on China’s policy trajectory. In the highly sensitive military-security area, Beijing’s policy exhibited both continuity of existing principled neutrality and the ability/potential for change along the line of “constructive involvement.” Immediately after the start of the Ukraine war in late February, Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hua Chunying said that Russia was capable of coping with the situation in Ukraine on its own and did not need China’s military support. As the war dragged on and tension on the Taiwan issue rose, “China has presented in Moscow major equipment of its army, navy and air force. The Russian military would be instantly modernized if it takes them,” said a Chinese observer. In retrospect, China had traveled quite a distance from Hua Chunying’s February statement.

Shortly after the Ukraine-Crimea crises in 2014, this writer predicted in a publication for the US Army War College that “…a real and close alliance between Moscow and Beijing…is neither likely nor necessary in the short and medium terms, unless the core interests of both are perceived to be jeopardized at the same time.” In the summer of 2022, Pelosi’s Taiwan trip in the middle of Russia’s Ukraine war created not only a perfect storm in US-China relations deriving largely from US domestic politics (Bloomberg’s interview of Kissinger on July 19), but also forced Beijing and Moscow to reconsider their ties between a partnership with “unlimited cooperation” and a typical military alliance with binding security commitment.

The winds of a wider war were blowing. The question was how strong they would become.

Conclusion: “End of History” with the Last Soviet Man?

One did not need to wait for long as August turned to be more eventful and consequential than expected. On Aug. 30, the passing of Mikhail Gorbachev—the last and longest-lived Soviet leader—was the end of something: be it post-Cold War triumphalism, the pessimistic “unipolar moment,” or “liberal international order” whose rise and fall had been hotly and fashionably debated by Western political and intellectual elite in the past decade. Regardless, Gorbachev’s legacy will continue to impact the world, including Russia and its largest neighbor, China.

Putin bid farewell to, but did not attend the funeral of, the first and last president of the USSR who, perhaps unintentionally, started a curious cycle of asymmetrical perceptions of Soviet/Russian leaders in the eyes of Russians and Westerners: popular in the West but hated at home, or vice versa. One wonders if Putin and his successors care about this binary.

Figure 8 Russian President Vladimir Putin pays his respects to the former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev at the Central Clinical Hospital in Moscow. Photo: China.com

For many in China, Gorbachev’s effort to normalize relations with Beijing was recalled as “a huge historical accomplishment in Sino-Soviet relations,” according to late Foreign Minister Qian Qichen. In fact, the current “best-ever” strategic partnership could be traced all the way back to the last Soviet leaders, particularly Gorbachev, who was instrumental in removing the “three obstacles“ in Sino-Soviet relations: Soviet troops in Afghanistan, Soviet support for Vietnamese troops in Cambodia, and Soviet military concentrations along the Chinese border.

In the last few Soviet years, Gorbachev’s daring and controversial domestic reforms of Glasnost (гласность) and perestroika (перестройка) were closely watched by a generation of Chinese. “Gorbachev represented a generation of Soviet reformers who intend to transform the overly centralized Soviet politico-economic systems,” said Feng Shaolei, an authoritative Russologist in Shanghai. Years after the Soviet implosion, Gorbachev reportedly confided to a senior Chinese diplomat that “the Soviet Union collapsed because there was no Deng Xiaoping in Russia.” Gorbachev did not specify how so much was owed by so many to just one person. His romantic and rapid reforms were nonetheless in sharp contrast to Deng’s gradualist and pragmatic ones. Reforms were difficult and even dangerous, noted a Chinese observer, particularly in large countries like China and Russia. Regardless of the outcome of these reforms, both China and Russia faced a race between forces destroying the old system and rebuilding new ones. And the rest was history.

Beyond Russia and China, there was little left of the legacy of Gorbachev’s “new thinking” (новое мышление) of reconciling with the West. Post-Soviet Russia had never been at ease with the West even during the good-old days of Yeltsin. In fact, the current Russian leader declared just a few months before Gorbachev’s passing that “[T]he era of a unipolar world order has come to an end.”

As a result, Aug. 24 marked a strange day, observed Wan Qingsong, a young Chinese Russia specialist in Shanghai. It was the 30th anniversary of Ukraine’s National Day (in the wake of the Soviet collapse) and six months of Russia’s special military operations to de-militarize and de-Nazify this former Soviet republic that, paradoxically, contributed significantly to the Soviet defeat of Nazi Germany in WWII. Meanwhile, more weapons were pouring into Ukraine ($8 billion US commitment) and Russia was mobilizing an additional 137,000 troops. Neither had made any significant change on the front. In August, even Europe’s largest Nuclear Power Plant in Zaporizhzhia was constantly shelled (Russia took it in March).

For many in Europe, Gorbamania had evaporated long time ago. Gone with it was a generation of European statesmen: Helmut Kohl, Margaret Thatcher, and Angela Merkel. In the immediate future their successors face the largest-ever wildfires, rapidly rising inflation, and paradoxically, a growing “Ukraine fatigue.” With all these preoccupations at home, rising tension in the east served as both a temptation for and diversion from Europe. In contrast to West’s indirect role in the Ukraine war, however, Taiwan and the looming US-China confrontation would make Ukraine child’s play.

“We are at the edge of war with Russia and China on issues which we partly created, without any concept of how this is going to end or what it’s supposed to lead to,” warned Henry Kissinger in his Aug. 12 interview with WSJ. This was just one of the four warnings voiced in May-August by Kissinger (others being June 11, July 18, and Aug. 19), the last living architect of the post-Cold War system after Gorbachev.

Both Gorbachev and Kissinger were marginalized in their respective homeland, though for different reasons. Ironically, a thinker and practitioner of the art of equilibrium like Kissinger is better received in Beijing and Moscow. The world, however, is helplessly moving into a “dangerous disequilibrium” at the dawn of Kissinger’s centenarian status.

One wonders if history might really come to an end this time.

May 5, 2022: Chinese Ambassador to Russia, Zhang Hanhui praises deepening China-Russia strategic cooperation on energy projects, military technology, and space issues during an interview with TASS.

May 13, 2022: Dai Bing, China’s deputy ambassador to the United Nations, supports Russia’s claim in a UNSC meeting that the US conducted covert biological research activities in Ukraine.

May 16, 2022: China’s Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian rejects the G7 Foreign Ministers’ Communiqué issued May 14, which urged China to not support Russia in the war, not undermine sanctions imposed on Russia, and “desist from engaging in information manipulation, disinformation and other means to legitimize Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine.”

May 19, 2022: BRICS holds its annual foreign ministerial meeting via video. A joint statement is released calling for dialogue between Russia and Ukraine. It did not use the term “invasion.” Chinese FM Wang Yi criticizes the West’s “absolute” and “unilateral” security policies, as well as arms supply to Ukraine. He also proposed to explore the potential and procedure for BRICS expansion, including mechanism such as BRICS-plus.

May 23, 2022: President Biden compares Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to the possibility of China taking Taiwan by force.

May 23, 2022: Russian FM Lavrov states that Russia would focus on developing relations with China and “reliable” countries to reduce its dependence on Western imports.

May 24, 2022: Two Russian Tu-95MS and two Chinese H-6K strategic bombers conduct annual joint aerial patrol over the waters of the Sea of Japan and the East China Sea. President Biden was in Japan for the 2nd day of his official visit.

May 26, 2022: Chinese envoy to the WHO Yang Zhilun votes against a US-backed proposal condemning Russia for creating a health emergency in Ukraine. The resolution was approved by a majority.

May 26, 2022: Russia and China veto a UNSC resolution on the DPRK (North Korea) for its recent missile tests.

May 26, 2022: In a speech to George Washington University, US Secretary of State Blinken calls China most serious long-term threat to world order while Russia “poses a clear and present threat.”

May 26, 2022: Russian FM Lavrov says in an interview with RT that NATO’s next ‘line of defense’ will be moved to the South China Sea.

June 1, 2022: China FM Wang Yi says that “China is willing to work with the Russian side to continue to implement the important consensus of the two heads of state and promote the development of the global governance system in a more just and reasonable direction.” Wang gave the video speech at a forum held by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and the Russian International Affairs Council. Wang’s Russian counterpart Lavrov also attended.

June 2, 2022: A video conference is held by technical, transportation and economic planning experts from China, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan. They had a “thorough exchange of views” on construction of the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan (CKU) railway, which had been shelved for 25 years at least partially because of Russia’s reservation. The CKU will cut the freight journey between China and Europe by 900 km and 7 days compared with the current Russian and Kazak transit routes. Construction will begin in 2023.

June 7, 2022: Chinese State Councilor Wang Yong says at a virtual meeting with Russia’s envoy to the Volga Federal District that China and Russia had elevated their “level of cooperation under new circumstances.” Both agree to deepen cooperation between local governments of the two countries via the “Yangtze-Volga mechanism.”

June 8, 2022: The 3rd “China+Central Asia” (C5+1) Foreign Ministers’ Meeting was held in person in Nur-Sultan (Astana before March 2019). The five Central Asian countries are Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. C+C5 ministers all agreed to elevate C+C5 by setting up a mechanism of C+C5 head of states summit. In March, the US (Blinken) and C5 held the 3rd C5+1 foreign minister meeting via video. The first one was held in November 2015 with John Kerry as US Secretary of State.

June 11, 2022: Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy says at the Shangri-La Dialogue that the world must not leave any country behind that is “at the mercy of another country which is more powerful, in financial terms, in territorial terms, and in terms of equipment.” He did not mention tensions between Taiwan and China in a Q&A after his formal speech.

June 12, 2022: Chinese Defense Minister Wei Fenghe says that “on the Ukraine crisis, China has never provided any material support to Russia,” adding that “China-Russia relations is a partnership, not an alliance. It does not target any third party.”

June 15, 2022: Xi and Putin talk over the phone. They reaffirmed support to each other in the economic, diplomatic and security areas. Putin briefed Xi on Russia’s operations in Ukraine. They also discussed mil-mil relations.

June 16, 2022: Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Wang Wenbin says that China and Ukraine “maintain open and smooth lines of communication.”

June 22, 2022: In his virtual speech at the BRICS Business Forum, President Xi criticizes military alliances and hegemonism that led to the Ukraine crisis. Xi also promoted the concept of “indivisible security” in his Global Security Initiative unveiled in April 2022.

June 23-24, 2022: President Xi chairs the BRICS 14th summit in Beijing via video. The summit’s Beijing Declaration was adopted and released at the event. Both Xi and Putin joined the event via video. Membership expansion was a key issue for the summit.

July 7, 2022: Chinese FM Wang Yi meets Russian FM Lavrov on sidelines of the G20 Foreign Ministers Meeting in Indonesia. Wang repeated China’s claim to hold an “objective and impartial” position on Russia’s special military operation in Ukraine, while confirming deepening bilateral cooperation with Russia.

July 14, 2022: Chinese FM Wang Yi criticizes US effort to divide Russia and China when he was interviewed by Chinese media.

July 22, 2022: Special Representative of the Chinese Government on Korean Peninsula Affairs Liu Xiaoming has a phone call with Vice Foreign Minister Igor Morgulov of Russia. They exchange views on the situation on the Korean Peninsula. The two agreed to maintain close coordination regarding the Korean issue.

July 28-29, 2022: Shanghai Cooperation Organization holds its annual foreign ministerial meeting in Uzbekistan. Wang Yi and Lavrov joined the session.

Aug. 2, 2022: Kremlin Spokesman Dmitry Peskov describes Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan as “purely provocative.” Vladimir Dzhabarov, First Deputy Chairman of the International Committee of Russia’s Federation Council, or upper house of Parliament, goes as far as to say that Russia may offer assistance to China if asked.

Aug. 3, 2022: Russian FM Lavrov says, regarding Pelosi’s Taiwan visit, that he did not see any other “reason to create such an irritant literally out of nowhere.”

Aug. 4, 2022: Deputy Chairman of the Russian Security Council Dmitry Medvedev (Russian president in 2008-12 and prime minister in 2012-20) calls Speaker Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan a “malicious provocation.”

Aug. 5, 2022: Russian FM Lavrov meets in Phnom Penh with Chinese counterpart Wang Yi. They criticized “the policy of lawlessness, demonstrated by the US colleagues, who are seeking to establish their dominance.”

Aug. 10, 2022: TASS cites Chinese Ambassador Zhang Hanhui as saying that the US the West was now “replicates Ukrainian scenario regarding Taiwan.”

Aug. 13-27, 2022: China participates in 8th annual International Army Games in Russia (main site) and 11 other countries.

Aug. 15-21, 2022: Army-2022 international military-technical forum including a military equipment expo kicks off at the Patriot Exhibition Center outside Moscow. The Russian Defense Ministry was the organizer of the event.

Aug. 16, 2022: Chinese Defense Minister Wei Fenghe addresses 10th Moscow Conference on International Security.

Aug. 16, 2022: In his speech to the 10th Moscow Conference on International Security, President Putin depicts Pelosi’s visit as “a thoroughly planned provocation.”

Aug. 18-19, 2022: Tashkent hosts SCO’s 17th Meeting of Security Council Secretaries under the presidency of Uzbekistan.

Aug. 30, 2022: Mikhail Gorbachev, first and last Soviet president, dies in Moscow. China expresses condolences over his. Chinese foreign ministry spokesmen Zhao Lijian says that “Mr. Gorbachev made positive contributions to the normalization of China-Soviet Union relations.”

Aug. 30-Sept. 5, 2022: Russia conducted its “Vostok” (East)-2022“ exercises involving 50,000 military personnel, more than 5,000 pieces of military equipment, including 140 aircraft, 60 warships, boats and support vessels. China, Algeria, India, Belarus, Tajikistan and Mongolia participated. The PLA sends 2,000 servicemen, 300 pieces of equipment, 21 airplanes, and three warships. Vostok-2018 included nearly 300,000 troops including for the first time from the Chinese army. The PLA claims that its participation “is unrelated to the current international and regional situation.”

Aug. 31, 2022: Outgoing Russian Ambassador to China Andrey Denisov meets in Beijing with Li Zhanshu, chairman of China’s National People’s Congress (NPC) Standing Committee. Li spoke highly of Denisov’s contribution to Sino-Russian relations.