Articles

In the last months of 2023, China and Russia increasingly prioritized economics and geoeconomics in their bilateral interactions. In the post-COVID era and with a virtual standstill in the Russian-Ukraine war, both sides searched for new growth potential in domestic, bilateral, and multilateral domains. In October, Russian President Putin visited Beijing for the 3rd Belt and Road Forum (BRF), which was attended by thousands of participants from 151 countries. It was a convenient occasion for Putin to expand his diplomacy, which had been considerably strained by Western sanctions since early 2022. Putin’s lengthy meetings (formal talks, a working lunch, and a “private tea meeting”) took almost half a day for the two-day BEF. Ten years after Xi’s launch of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), both sides found it necessary to adjust their policies between the increasingly globalized BRI and Russia’s regional grouping, the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU).

In many ways, the 28th regular prime ministerial meeting in Beijing in December was essential to manage key issues, including the routing and pricing of the Power of Siberia 2 gas pipeline (PS2) and the rapid growth of China’s automobile exports to Russia. Both were directly related to Western sanctions following Russia’s special military operations in Ukraine, now into its third year. At the year’s end, the death of Henry Kissinger marked the end of an era of more orderly superpower relations, to the dismay of both Russia and China.

Putin in Beijing

On Oct. 17-18, President Putin traveled to Beijing for the 3rd Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation (BRF). This was the first time the Russian president visited China since Russia’s “special military operation” in February 2022, but it was his third time attending the BRF (2017 and 2019). The two heads of state met in early March when Xi visited Moscow.

Despite the crowded schedule of the BRF and its 4,000 participants from 151 countries and 41 international organizations, Putin and Xi set aside about four hours together, which included 90-minute formal talks, a working lunch with “limited attendance” (foreign ministers of both sides), and a nearly two-hour “private tete-a-tete conversation.” Neither side disclosed the substance of the private meeting. Putin, however, revealed that it was “a very productive and substantial part of the conversation.”

The Xi-Putin talks covered “entire bilateral issues” including economics, finance, political interactions, and diplomatic coordination, according to Russian sources. President Xi emphasized the “long-term” nature of the bilateral relationship. It was “not an expediency” but a “permanent good-neighborly friendship” with “comprehensive strategic coordination and mutually beneficial cooperation,” said Xi.

For Putin, it was “particularly relevant” to maintain close foreign policy coordination with China given the “difficult current conditions.” In his press conference with Russian media, Putin revealed that he briefed the Chinese side on “details” of Russia’s military operations in Ukraine. China’s press release, however, did not mention the Ukraine issue. Instead, it stressed that the two heads of state “had an in-depth exchange of views” (深入交换了意见) on the Middle Eastern situation.

Aside from meeting Xi, Putin’s Beijing visit was an important opportunity for the Russian leader to reconnect in person with many heads of state/government, including those from Vietnam, Hungary, Thailand, Mongolia, Laos, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan. Putin traveled only to Kazakhstan since February 2022. He skipped the annual BRICS summit in late August in South Africa because of the host’s membership in the International Criminal Court, which issued an arrest warrant against Putin for alleged war crimes in Ukraine.

Beyond these mini-summits between Putin and other state dignitaries on the BRF’s sidelines, the Russian leader was prominently treated throughout the two-day forum (see group photos for the official welcoming ceremony on Oct. 17 below). Xi devoted half of the entire forum day (Oct. 18) to the Xi-Putin talks. This included an almost two-hour ad hoc private “tea talk” suggested by Xi following formal talks with expanded participants and a working lunch.

Figure 1 The heads of delegations participating in the Third Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation were formally welcomed during the official welcoming ceremony. Photo: Sergei Savostyanov

There was no question that the two heads of state have developed “good business-like relations and a strong personal friendship” in their decade-long interactions (42 meetings since 2013 according to Xi’s account). Xi was “a calm…and reliable partner” and “a true world leader” who “who makes all of his moves with long-term goals in mind,” remarked the Russian president shortly before his trip to the BRF.

Tales of Two Regional Projects: BRI vs EAEU and beyond

One of Xi’s “long-term” projects was the BRI. Originally driven by China’s excess manufacturing capacity, Xi proposed it in September 2013 during his tour of Central Asia as China’s regional strategy in Kazakhstan. A few months later, Russia unveiled the EAEU as its own integration mechanism for the post-Soviet space.

Ten years later, the BRI has become a global project connecting more than 150 countries with more than 3,000 cooperation projects, nearly $1 trillion in investments, and more than 20 multilateral dialogue/platforms in sectors of railway, port, finance, taxation, energy, green development, green investment, disaster risk reduction, anti-corruption, think tanks, media, culture exchanges, etc.

The BRI was “a truly important and global idea that is spearheaded into the future, towards creating a fairer multipolar world and system of relations. It is a global plan, without a doubt,” remarked Putin in his address at the BRF opening ceremony on Oct. 17. This, however, was a long way from Russia’s rather alarming view of the BRI 10 years before (see “Putin’s Glory and Xi’s Dream,” Comparative Connection, January 2014). In responding to a reporter’s question about China’s BRI competing with Russia’s EAEU shortly after meeting Xi, Putin insisted that the two projects “complement each other.” This was because China’s BRI “is a global initiative and concerns practically every region of the world…and Russia as well.” Meanwhile, EAEU was a local project, explained Putin. But “it is an absolute priority for us, for Russia,” he stressed.

The bulk of Putin’s speech at the BRF opening session was devoted to Russia’s efforts to develop EAEU’s energy and transportation infrastructure. The EAEU would interact with BRI, the SCO, BRICS, and ASEAN under the umbrella of what Putin defined as “a greater Eurasian space.” For this, Putin cited an agreement and a joint commission by the EAEU and BRI for “a concurrent and coordinated development” between the two sides.

Beijing was keenly aware of Russia’s sensitivity regarding the growing gap in terms of comprehensive national power between China and Russia. In Beijing, Xi expressed gratitude for Putin’s attendance at all three BRFs since 2017. The Chinese president described Russia as “an important partner,” and that China was willing to work with Russia and the EAEU to promote the BRI-EAEU alignment for “higher-level and deeper regional cooperation.”

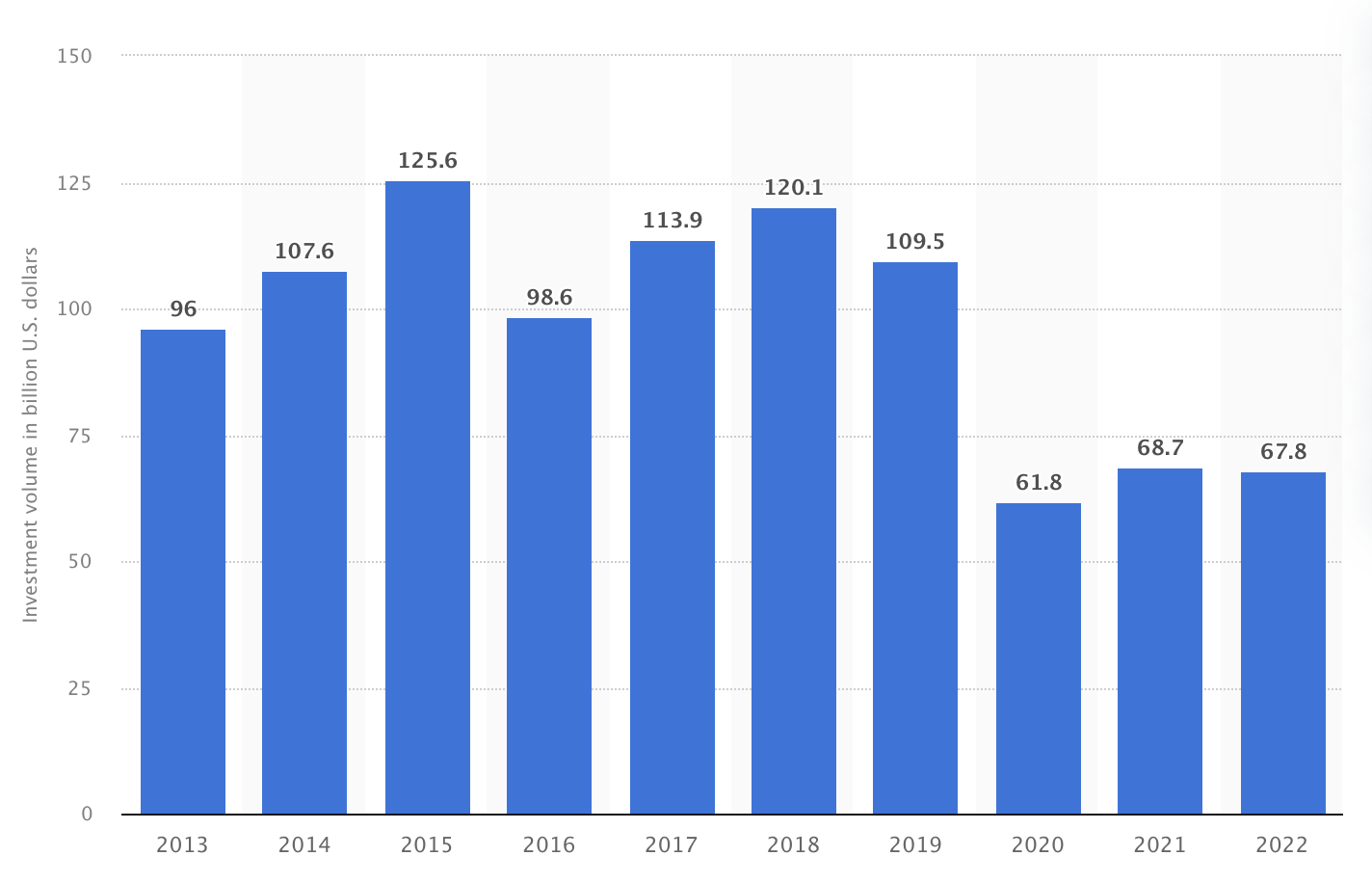

For Beijing, Moscow was not just another BRI partner but one with strategic stakes, particularly in the wake of a significant slowdown (-40% to -45%) of its external outreach/investment through the COVID years (2020-2022).

Figure 2 Chinese BRI investment: 2013 – 2022 (in billion U.S. dollars). Photo: Statista

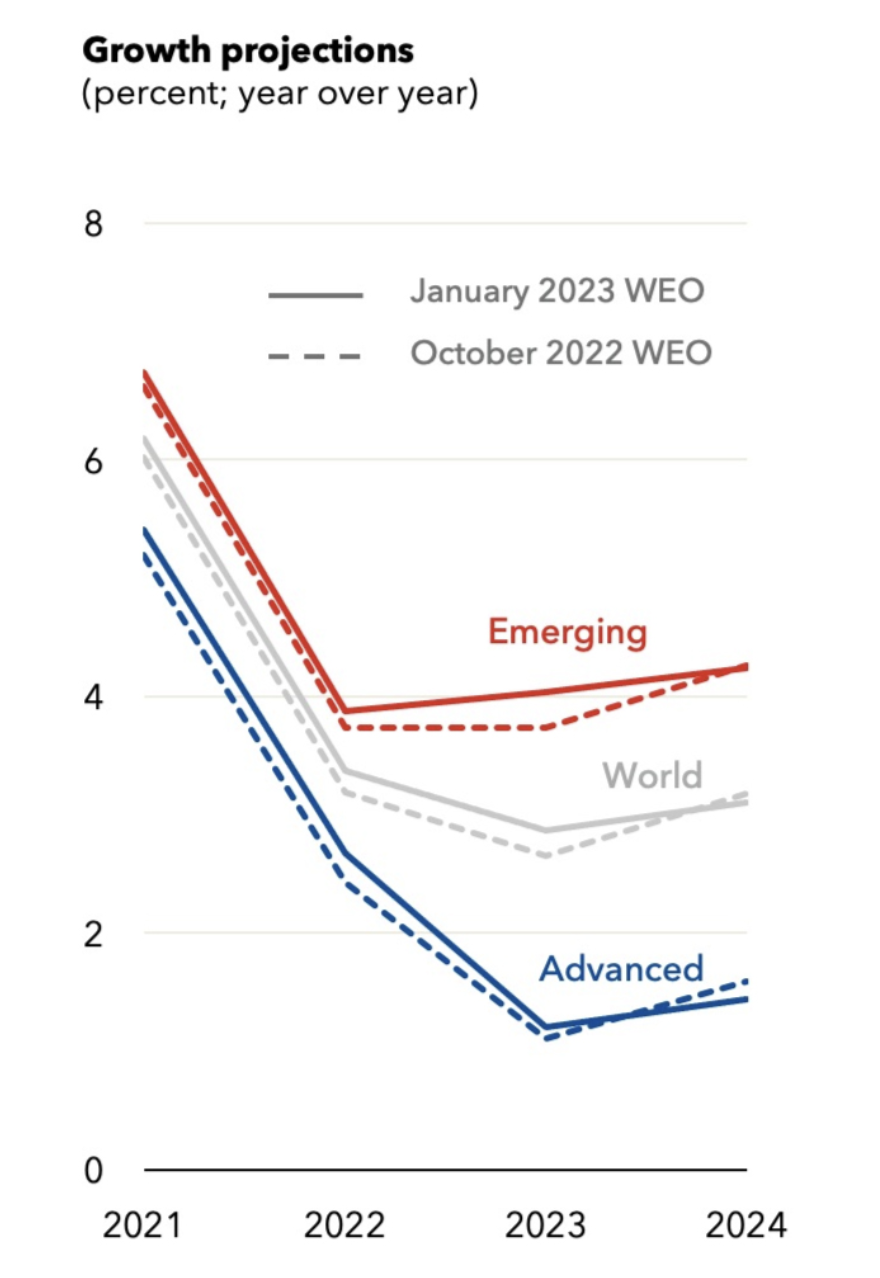

In the future, BRI must cope with and adjust to a general downward trend in the world economy starting in 2021 (see IMF projection below). Western sanctions against both Russia and China have had a disruptive impact on the world’s largest resource country (Russia) and manufacturing giant (China). Both must search for alternative venues to overcome these natural and manmade hurdles. Moscow, for example, needs to divert its energy exports away from Europe.

Figure 3 Global growth projections starting in 2021. Photo: IMF

For China, the future of BRI lies in emerging markets that have already bottomed out as a group with 4% growth rate vs. the advanced economies’ 1.2-1.4% growth. It is questionable if previous investment in large infrastructure projects for BRI recipients will be viable, at least in the near future. The 3rd BRF, accordingly, made several major adjustments in its future strategies. One is the 1,000 “small-and-smart livelihood projects” as part of the “practical cooperation.” For this, China will set up a RMB 700 billion (about $98 billion) financing window. An additional RMB 80 billion will be injected into the Silk Road Fund. Already, $97.2 billion worth of agreements were already signed during the 3rd BRI in Beijing. Meanwhile, considerable effort would be devoted to the safety and security of BRI projects and personnel, green projects with 100,000 training opportunities by 2030, 100 high-tech and AI labs in five years, people-to-people exchanges, anti-corruption for “integrity-based projects, etc. While BRI’s traditional connectivity projects need to be upgraded to “high-quality” and account for reliability, new venues such as digital trade service trade and investment will be sped up. At the BRF, China also promised to remove all restrictions on foreign investment access in the manufacturing sector. All this would facilitate “an open world economy” in the next five years (2024-28) with the country’s total trade in goods and services exceeding $32 trillion and $5 trillion, respectively.

Trade with Russia in 2023 (for the first 11 months) was only 4.2% of China’s $5.41 trillion in global trade. Aside from the need to maintain normal and stable ties for the long run, China considered Russia to be playing a salient role in Beijing’s diplomatic matrix for at least three reasons. First, Russia was essential in the operation of all the multilateral platforms of the “global south” such as the SCO, BRICS, BRI, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the New Development Bank (NDB, for BRICS), etc. The February 2022 Russian-Ukraine war and the ensuing Western sanctions fundamentally reoriented Russia away from the West. Speaking to the 8th Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok on Sept. 12, 2023, President Putin declared that “the Far East is Russia’s strategic priority for the entire 21st century, and we will stick to this.” In 2024, Russia will take over BRICS chairmanship when five new members (Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates) join. In addition to the annual BRICS summit in Moscow in August, over 200 events of different levels and types will be held across Russia. After missing the 2023 BRICS summit in Johannesburg, Putin is determined to make it back for both symbolic and substantive purposes.

Second, given BRI’s future focus on sustainable, smaller, and greener development, Russia is perhaps the only place where large-scale infrastructure projects were still possible and desirable regardless of bureaucratic hurdles and regional underdevelopment. In formal talks in Beijing on the BRF sidelines, Xi cited the current China-Russia east-route natural gas pipeline (Power of Siberia) as a successful “major infrastructure project” with “tangible benefits to the people of both countries,” and urged that “substantive progress” was needed “as soon as possible” for the China-Mongolia-Russia natural gas pipeline project (Power of Siberia 2, or PS2).

Last, Russia registered higher-than-expected economic growth in 2023 (3.5% vs. 2.1% in 2022) despite the war of attrition with Ukraine. Russia-China trade, too, grew by 26.7% to $218.176 billion from January to November 2023, surpassing the $200 billion goal set for 2024.

Russian PM in China: For the Not-So-Stupid Economy

On Dec. 19-20, Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin went to Beijing for the 28th regular prime ministerial meeting with Chinese counterpart Li Qiang. This was his second visit to China in 2023. In late May, Mishustin made his first official trip to China as Russian PM. Previously, Covid-19 had prevented in-person contact by the two countries’ top officials. The Li-Mishustin meeting covered an extensive range of items, including energy (oil, gas, nuclear, green), connectivity, trade, investment, finance/banking, supply chain stability, science, regional development, environmental protection, sustainable development, societal exchange, etc. For the two prime ministers, there was much to catch up after three years of COVID “break.” Ten documents/agreements were inked in Beijing, including a 9,000-word (Chinese characters) Joint Statement.

President Xi Jinping met with Mishustin after the prime ministers’ annual meeting. Both were encouraged by the 26% bilateral trade growth for 2023 surpassing the $200 billion target set for 2024. The figure is expected to reach $230 billion by the year-end given the strong momentum. And “over 90 percent of our transactions are made in rubles or yuan,” Mishustin remarked.

The Russian side indicated that “good results have been achieved in the investment sphere, with 80 joint projects currently in progress totaling almost 20 trillion rubles, or about 1.6 trillion yuan (about $221 billion).” China’s official Xinhua news release did not mention specifics of the joint projects but said that the Russian PM “is satisfied with the steady growth of bilateral practical cooperation and is willing to work with China to further tap potential, expand cooperation in fields such as economy, trade, energy, and connectivity.”

For Xi, “maintaining and developing China-Russia relations is a strategic choice (战略选择)” and “China supports the Russian people in taking the development path of their own choice.” He also hoped the 75th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Russia in 2024 would be “a new starting point” for the two sides to develop bilateral ties. As part of the societal exchange program, 2024-25 will be the “China-Russia Cultural Year.”

Russia’s energy export to China was a key issue for the prime ministers. In 2023, almost all Russia’s oil exports went to China (50% or about 100 million tons) and India (about 40% or 70 million tons), while Europe-bound oil products fell from the pre-Ukraine war volume of 40-45% to 4-5%, according to Russian accounts.

Russia’s successful redirection of much of its oil exports from Europe to Asia in 2023 explained a slight decrease in its annual oil production (1.5%), from 535 to 527 million tons. Russia’s gas output, however, registered an 8.5% drop in the first 11 months of 2023 largely because of a steep decline of gas exports to Europe after the September 2022 destruction of the Nord Stream 2 (55 billion cubic meter annual capacity). Meanwhile, Russia’s gas exports to China via the existing Power of Siberia (PS) pipeline rose sharply in 2023 to 22.5 bcm, a 45% increase from 15.5 bcm in 2022. By 2025, PS will reach its design capacity of 38 bcm. In 2027, completion of a connection line to the Far Eastern route (Sakhalin–Khabarovsk–Vladivostok pipeline) will add another 10 bcm per year, according to a Nov. 2023 agreement between Gazprom and CNPC. This means that the full capacity of the China-bound PS will be 48 bcm by 2027, which is still less than half of what Russia lost from Nord Streams 1 and 2 (110 bcm). Finding alternative destinations for Russia’s idled gas capacity was paramount for Moscow.

For years, Russia had toyed with the idea of a second gas pipeline to China. In the past few years, it evolved to a pipeline via Mongolia to be known as Power of Siberia 2 (PS2) with an annual capacity of 50 bcm. In their March 2023 meeting in Moscow, Putin and Xi discussed PS2. The signed Si-Putin joint statement, however, did not mention it. Nor did Xi talk about it in the post-summit press conference with Putin. The Russian president, however, stressed that he and Xi “discussed this in detail and have reached corresponding agreements with Mongolia.”

Figure 4 Trans-Mongolian Route for Power of Siberia 2. Photo: China’s Resource Risks

The two sides continued to work on the PS2 in the ensuing months while Russia pushed for its closing by the year end. The December PM meeting in Beijing was unable to close the deal. Instead, the two prime ministers “called for reaching agreements on the construction of the PS2 gas pipeline as quickly as possible,” according to Russian Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak.

Pricing and/or routing (via Mongolia) may not be the only drivers for the alleged “delaying action” by China as Moscow was said to have less bargaining power than Beijing in the post-Nord Stream era. China-Russian energy cooperation, however, has assumed new dimensions. In the 20th meeting of the Russian-Chinese Intergovernmental Commission on Energy Cooperation shortly before Mishustin’s trip to Beijing, Chinese Vice Premier Ding Xuexiang told Russian counterpart Alexander Novak that the two sides should explore new directions, broader scope, higher-level, and more integrated “all-spectrum” (上中下游一体化) cooperation. This included renewable, green, smart sectors, nuclear, hydrogen as well as energy storage and transmission. The Russian government readout of the Novak-Ding meeting, however, clearly prioritized energy export to China, while insisting on “the principles of equality, mutual respect and a readiness to provide strong mutual support on issues related to our national interests.”

2023: From China, with Cars

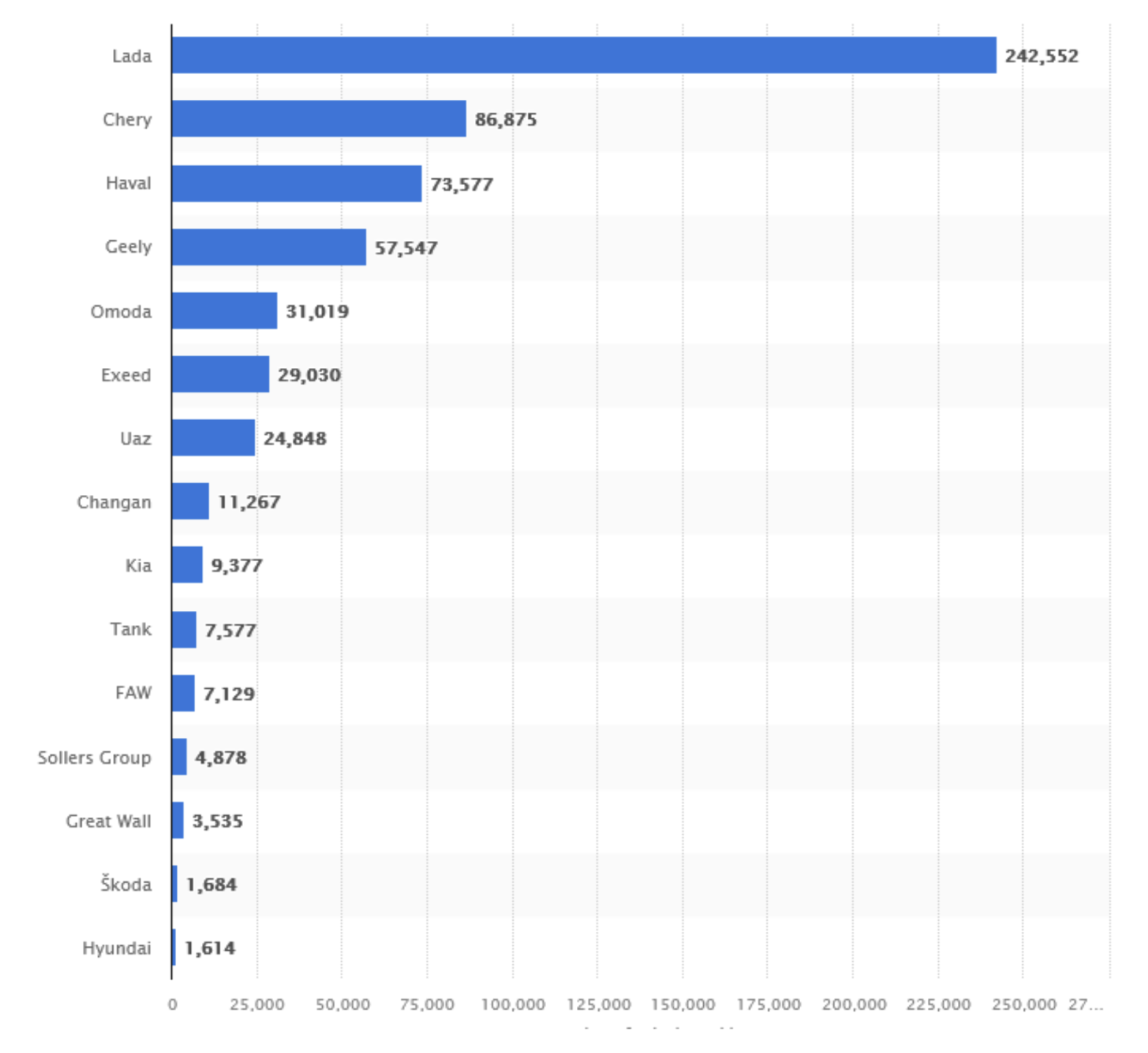

It was unclear if China’s “new thinking” in energy cooperation with Russia was part of the “strategic emerging industries (战略性新兴产业)” that President Xi urged Putin to “actively explore cooperation” with China. Already, 2023 was marked by phenomenal growth of China’s export of consumer products to Russia, ranging from flat panel TVs, office supplies, home electronics, etc. A case in point was a dramatic surge of Chinese automobiles to Russia from 160,000 units (8%) in 2022 to 736,000 (56.6%) in the first 10 months of 2023. This was the single biggest factor that turned China into the world’s largest car exporter (4.41 million vs Japan’s 3.99 million for the first 11 months of 2023).

Largely because of China’s inputs, the Russian car market had a huge rebound in 2023 with staggering 60% growth to 1.3 million units from 2022 when the Russian auto market dropped 58.8% (687,370 units) from 1.7 million units in 2021. Most of the growth occurred in sectors abandoned by Western, Japanese, and South Korean car companies but are being rapidly replaced by Chinese brands. In the first three quarters of 2023, nine of the 15 top car companies were from China (Chery, Haval, Geely, Omoda, Exceed, Changan, Tank, FAW, and Great Wall; see chart below). Russia’s Lada (made by Russia’s largest state-owned AvtoVAZ) was still the top seller, but only with significant components and know-how inputs from China. Meanwhile, the two South Korean brands (Kia and Hyundai) were basically selling the remainder of their inventories.

Figure 5 Sales volumes of passenger cars and light commercial vehicles (LCVs) in Russia from January to September 2023, by manufacturer. Photo: Statista

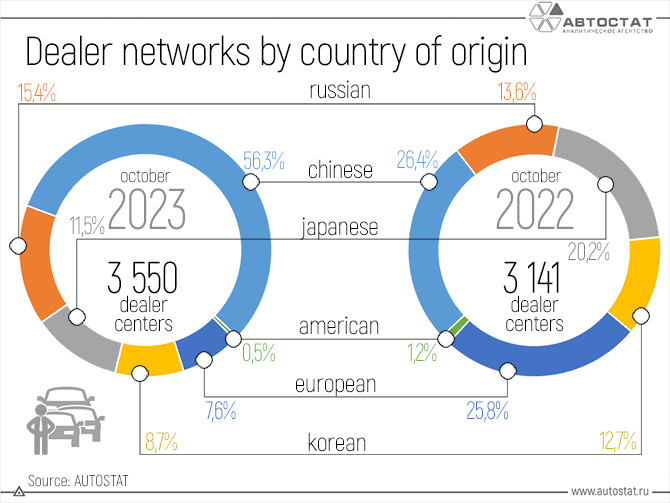

The steep rise of Chinese vehicles in Russia was both the cause and effects of an explosive expansion of car dealers of Chinese brands in Russia. In one year alone, the number of Chinese car dealers more than tripled from 527 (26.4%) to 1999 (56.3%) at the expense of European (-18.2%), Japanese (-8.7%), and Korean dealers (-4%).

Figure 6 More than half of all car dealers in Russia are Chinese brands. Photo: Autostat, Russia

Behind the rapid rise and fall of foreign car dealers in Russia was the Russian government’s determined actions to replace auto plants of “unfriendly countries” with friendly and more efficient Chinese manufacturers. On May 19, German carmaker Volkswagen (VW) finalized the sale of its Kaluga production plant in Russia to Art-Finance, a subsidiary of Russia’s auto dealer Avilon. Four days later, Russian PM Mishustin paid his first official visit to China with more than 500 Russian businesspeople. His trip started from China’s business/industrial/finance center Shanghai to “prioritize interactions in industry…,” reported TASS. In his address to the Russian-Chinese Business Forum in Shanghai, Mishustin stressed the “harmonization of national standards and technical requirements” for joint initiatives in “knowledge-intensive industries …such as civil aviation and the automotive industry.” In mid-June, the former VW plant in Russia was reportedly acquired by China’s Chery auto group, which would resume operation in the fall. By year’s end, Art-Finance closed another deal with a Hyundai’s plant in St. Petersburg (200,000 units annual capacity and worth $221 million) for a symbolic $110. Meanwhile, several leading Chinese car makers (Chery, FAW, etc.) were reportedly working with Russia’s flagship automaker AvtoVAZ to produce Chinese brands in the St. Petersburg plant.

The Hyundai plant transaction coincided with the Russia-China annual prime ministerial meeting in Beijing (Dec. 19-20). Two days after his return, Mishustin chaired the first Cabinet meeting to “prioritize support” to Russia’s auto industry to “develop the missing competences in a short period of time and fully guarantee stable functioning of assembly lines in under the sanctions.” He cited Putin’s instruction “to expedite the development and production of the entire range of critical automotive components.” This “ambitious plan” would be assisted by “additional 39 billion rubles (about $427 million)” for Russia’s leading domestic automakers for their R&D and engineering.

Russia’s open-door policy to Chinese autos was driven by both expedient and long-term considerations. Sales dropped by a million units, or 60% in 2022 as a result of the abrupt halt of Western auto assembly plants in Russia. Meanwhile, China’s car export started to surge largely because of cut-throat competition at home. In 2021, China’s car exports surpassed those of South Korea, then Germany in 2022, and Japan in 2023. In his meeting with Mishustin in December, President Xi talked about the “strong resilience, great potential and wide room for maneuver, and the long-term sound fundamentals” of the Chinese economy.” China’s “high-quality development and high-level opening up” meant new opportunities for many countries including Russia, remarked Xi to Mishustin.

That opportunity was open to the reeling Russian auto sector with tens of thousands of idled workers. China was not only able and willing to jumpstart Russia’s auto assembly lines, but was also willing to transfer technology. This final reckoning was not easy for the Russians as many of them long favored Western brands. Others lived in the past with lingering nostalgia for Soviet times when Moscow’s massive economic assistance to China (about $300 million in 1950) literally created China’s industrial base. Few, if any, Russians knew that China’s FAW, or First Auto Works in Changchun (长春), now actively operating in Russia to fill the void of Western companies, was the only automobile plant of the 156 large enterprises created by Soviet assistance 70 years ago. The largest of the Chinese auto firms in Russia now are privately owned, such as Chery, Geely, Haval (by the Great War Motor), etc. All of them, including the state-owned FAW had gone through the slow, costly, painful, and sometimes humiliating interactions with Western/Japanese/Korean car companies in the early decades of reform. Meanwhile, China expected its car producers “to uphold the image of their brands,” said Chinese Ambassador Zhan Hanhui in late November. “China is ready to…meet the demand of the Russian market, ensure first-rate quality, provide high-quality services, as well as facilitate the integration of production and supply chains in the two countries’ automobile sector,” added Zhang.

In the longer term, Russia aims to have the most advanced automobile technology and most efficient manufacturing knowhow in the world. In intensive interactions with China at both the high level (four mutual visits by Xi, Putin, and Mishustin in 2023) and on factory floors, Russian political and business elites seem convinced that China already leads the global auto industry. Most Chinese auto exports to Russia in 2023 were traditional gas-powered units given the much colder climate. Chinese companies are also leading the world’s electric car sector. In 2013, China’s BYD produced more than 3 million new energy vehicles in 2023, surpassing Tesla for a second straight year. Although Tesla continued to lead in battery-only passenger cars in 2023 (1.84 million vs. BYD’s 1.6 million), BYD outpaced Tesla in the last quarter of 2023 with 525,409 units vs Tesla’s 484,507 in the pure electric sector. Meanwhile, BYD produces the world’s most advanced battery, the “Blade,” which is the top choice for many automakers such as Mercedes, Ford, and Kia. “China is the world’s leader in EV battery production,” dominating almost “every stage of the EV battery supply chain,” according to a recent report by the International Energy Agency (IEA). “I would not be surprised if in 10 years such companies as Mercedes and BMW will go into history. As brands they will probably remain, but they will follow the fate of Volvo, which was sold to China,” predicted Russian presidential aide Maxim Oreshkin at the end of 2023.

For Russians, working with the leading auto giant is a strategic choice. As Chinese imports were rapidly filling the void created by Western sanctions in 2023, Russia’s car sector is expected to engage in the coming years in “deep localization” particularly in the area of electronic automotive components, according to Deputy Head of the Ministry of Industry and Trade of the Russian Federation Vasily Shpak.

Kissinger’s Passing: End of an Era?

When Henry Kissinger passed away at the age of 100 on Nov. 29, the world had changed so much — yet so little, particularly in terms of Washington-Moscow-Beijing triangle politick. It was much because the Nixon-Kissinger team irreversibly shaped the US-Soviet bipolar world into a more dynamic tripolarity (adding China) with Washington taking a pivot position among the three. The ensuing arms control mechanisms with Moscow, coupled with a historical rapprochement with Beijing, essentially turned the second half of the Cold War into what John Gaddis defined as the “long peace.”

Toward the end of his life, however, Kissinger became visibly alarmed by a more fragmented, unpredictable, and more dangerous world. For him, this was reminiscent of both the pre-World War I world of major power rivalry sleepwalking into a war, and the first 15 years of the Cold War (1947-62) with the fast buildup of nuclear arsenals on both sides of the Iron Curtain. Worse, the rapid development of artificial intelligence (AI) may create the most toxic mix with WMD leading to the end of humanity (Kissinger, The Age of AI: And Our Human Future, Little, Brown and Company, 2019).

Moscow, Beijing, and Washington reacted to Kissinger’s passing in very different ways. In his condolence message, Putin described Kissinger as “wise, farsighted, profound and extraordinary.” For Putin, the ultimate contribution of Kissinger’s “pragmatic foreign policy” was the strengthening of global security with his “pivotal role in defusing international tensions.” In the past 22 years, Putin met Kissinger “more than 10 times” (the first meeting took place in July 2001, the last on June 29, 2017). This was perhaps far more than either Xi or Biden in their respective capacity as top leaders. One of Kissinger’s most profound insights was made at the height of the Ukraine-Crimea crisis in March 2014 when he warned that “[T]he test of policy is how it ends, not how it begins.” Now all war parties, direct or not, seem either looking/waiting for or thinking about an exit as the Ukraine war comes to a standstill.

For Xi Jinping, Kissinger was first and foremost “an old friend and good friend of the Chinese people” because “his outstanding strategic vision” led to his “historic contributions to the normalization of China-US relations.” Xi and Kissinger met the last time in July 2023 in Beijing. “The Chinese people value friendship,” said Xi to Kissinger, and that “We never forget our old friends.” In contrast to cool and business-like visits by US Secretary of State Blinken, Treasury Secretary Yellen and Climate Envoy Kerry, Kissinger was treated with warmth and “red carpet” treatment. He was even able to meet then Chinese Defense Minister Li Shangfu, who had refused to meet his US counterpart due to US sanctions against him.

President Biden offered a more personal condolence highlighting that they “often disagreed. And often strongly.” Biden nonetheless stressed Kissinger’s “fierce intellect and profound strategic focus.” Unlike Putin and Xi, Biden’s condolence message was issued a day after Kissinger’s passing. Aside from his measured message, Biden is perhaps the only president who did not invite Kissinger to the White House. It was unclear if Biden would send Kissinger an invite had Kissinger not died. For a sitting president who is fighting for his second term in a highly divided political atmosphere inside the Beltway, any liaison with a “China’s old friend” is a political liability. The Jewish immigrant who escaped to America at age 16 (1938) was ironically more respected outside his adopted nation, for better or worse.

Even if Kissinger was still alive, he would be very uneasy, if not alarmed, by the direction and momentum of the Russia-China-US triangular matrix in which Moscow and Beijing are moving increasingly toward a de facto entente. The potential between the world’s largest energy resource (Russia) and manufacturing giant (China) is a huge challenge for Washington, which was exactly what Kissinger had tried to prevent from happening.

Toward the end of his life, the biggest challenge for Kissinger was the internal decay of democracies, including the US. “I think democracy is in trouble… because the middle class is disappearing due to widening income inequalities,” remarked Kissinger in his last TV interview. “Values of compromise and understanding are in great danger in the West,” he added. Kissinger never explained the sources of his concerns about democracies. When he was born in 1923 in Bavaria Germany, the Weimar Republic (1919-33) still had a decade to go before Adolf Hitler was democratically elected. The ensuring chaos, violence, and war cast lasting impacts on the minds of the Jewish boy as many members of his family died in the Holocaust. This may well be the reason for Kissinger, at the end of his life, joined the pessimistic George Kennan, also a foreign policy strategist and a centenarian (1904-2005), who was horrified by the “decadence” of the 1960s and envisioned the end of Western civilization as occurring by 2050. For both President Biden and his political opponent (Trump), however, the make-or-break moment is not the distant 2050 but 2024.

Sept. 10-12, 2023: China’s Vice Premier Zhang Guoqing visits Vladivostok for the 8th Eastern Economic Forum. President Putin meets him Sept. 12. Zhang holds meetings with Russian Deputy Prime Minister Yury Trutnev, who is also Presidential Envoy to the Far Eastern District. Zhang also met Russian Deputy Prime Minister Denis Manturov, who oversees Russia’s industrial development.

Sept. 13, 2023: Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Ma Zhaoxu meets Russian Ambassador to Beijing Igor Morgulov in Beijing. The two discussed the preparations for the third Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation to be held in October.

Sept. 18-21, 2023: Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi visits Moscow to co-chair the 18th round of China-Russia strategic security consultations with Russian counterpart National Security Secretary Nikolai Patrushev. In Moscow, Wang first meets Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov who briefs Wang on the Ukraine issue and “applauded China’s position paper for accommodating the security concerns of all parties and being conducive to eliminating the root causes of the conflict.” Putin meets Wang on Sept. 20 and “reiterated Russia’s readiness to resolve the issue through dialogue and negotiation.” In Moscow, Wang also meets Mongolia’s Secretary of the National Security Council Enkhbayar Jadamba.

Sept. 19, 2023: China, Russia, and Mongolia hold the first trilateral meeting of high representatives for security issues in Moscow. Chinese FM Wang Yi, Secretary of the Russian Federation Security Council Nikolai Patrushev, and Secretary of the National Security Council of Mongolia Enkhbayar Jadamba are present. They discuss the China-Russia-Mongolia Economic Corridor and the proposed Power of Siberia 2 natural gas pipeline going through Mongolia. They also agree to further “institutionalize” the trilateral security dialogue.

Sept. 29, 2023: China’s Special Envoy on Afghan Affairs Yue Xiaoyong attends the 5th meeting of the Moscow Format Consultations on Afghanistan held in Kazan, Russia. Yue also holds a China-Afghanistan-Pakistan tripartite meeting with Acting Foreign Minister of the Afghan Interim Government Amir Khan Muttaqi and Pakistan’s Special Representative on Afghanistan Asif Durrani on the sidelines of the Moscow Format Consultations in Kazan.

Oct. 7, 2023: Vice Foreign Minister Ma Zhaoxu meets Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Rudenko Andrey Yurevich in Beijing. They have “an in-depth exchange of views” on China-Russia strategic partnership, as well as international and regional issues of interest and concern.

Oct. 16, 2023: Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi meets Russian FM Lavrov in Beijing ahead of the 3rd Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation (BRF). They also exchange views on the tension between Palestine and Israel.

Oct. 17-18, 2023: President Putin visits Beijing to participate in the 3rd Belt-Road-Initiative Forum. He holds talks with President Xi Jinping on Oct. 18.

Oct. 18-20, 2023: Fifth China-Russia Energy Business Forum is held in Beijing. Xi and Putin send congratulatory letters. More than 400 representatives from China and Russia attend.

Oct. 19, 2023: Special Envoy of the Chinese Government on the Middle East Issue Zhai Jun meets in Beijing with Special Presidential Representative for the Middle East and Africa and Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of Russia Bogdanov Mikhail. They exchange views on the Palestine-Israel situation.

Oct. 25, 2023: Chinese Premier Li Qiang and Russian PM Mishustin meet on the sidelines of the 22nd SCO annual PM meeting in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. Li tells Mishustin that “China supports enterprises from China and Russia in deepening cooperation on automobile manufacturing.”

Nov. 8, 2023: President Putin receives Vice Chairman of China’s Central Military Commission Zhang Youxia at the Novo-Ogaryovo residence outside Moscow. Zhang holds a “regular meeting of the commission on military-technical cooperation” with his Russian counterpart. Putin told Zhang that Russia and China “are not seeking to create any military alliances using Cold War-era templates and have been maintaining constructive ties which have become a serious stability factor globally.” He also speaks highly on economic relations with China.

Nov. 8, 2023: Fourth meeting of the council of cooperation between the upper and middle reaches of the Yangtze River and the Volga Federal District is held in Nanchang, Jiangxi Province. It is co-chaired by China’s Vice Premier Zhang Guoqing and Russia’s Presidential Plenipotentiary Envoy to the Volga Federal District Igor Komarov.

Nov. 20, 2023: Tenth meeting of the dialogue mechanism between the ruling parties of China and Russia is held online. Both Putin and Xi send congratulation messages.

Nov. 21-23, 2023: Chairman of the Russian State Duma Vyacheslav Volodin leads a delegation to China at the invitation of Zhao Leji, chairman of the National People’s Congress Standing Committee. President Xi meets Volodin on Nov. 22.

Nov. 29, 2023: Fourteenth Plenary Session of the China-Russia Friendship Committee for Peace and Development is held in Beijing. China’s Vice President Han Zheng meets representatives of both sides.

Dec. 12, 2023: China and Russia hold consultations on human rights affairs in Beijing. Special Representative for Human Rights of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of China Yang Xiaokun co-chaired the consultations with Russian counterpart Grigory Evguenievich Lukiyantsev, director of the Department for Humanitarian Cooperation and Human Rights of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Special Representative for Human Rights, Democracy and the Rule of Law.

Dec. 14, 2023: Russia and China conduct 7th joint air patrol over the Sea of Japan and East China Sea with Russia’s Tupolev-95MS strategic bombers and China’s Hong-6K strategic bombers. Russia’s Sukhoi-35S and China’s Su-30/Jian-11B provide support along the route. The first joint patrol was made in 2019.

Dec. 15, 2023: Chinese Vice Premier Ding Xuexiang and Russian Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak co-chair the 20th Russian-Chinese Intergovernmental Commission on Energy Cooperation in Beijing.

Dec. 18, 2023: China’s Finance Minister Lan Fo’an and Russian counterpart Anton Siluanov hold the 9th China-Russia Financial Dialogue in Beijing. They sign an MoU on audit standards and audit supervision to facilitate cross-border capital flow and bond issuance between China and Russia. They also agree to work with other multilateral forums for post-Covid recovery and to cooperate on BRICS’ New Development Bank (NDB) with its five new members starting from 2024.