Articles

Beijing confidently forecast continued advances in high-priority efforts promoting regional economic integration, ASEAN’s prominence as China’s leading trade partner, as well as strengthening supply chain connections disrupted by the pandemic and US trade and economic restrictions. Ever-closer cooperation to counter COVID-19 saw Chinese pledges add to its leading position providing more than 60% of international vaccines to Southeast Asian countries. Nevertheless, the unexpected coup and protracted crisis in Myanmar headed the list of important complications. The incoming Biden administration showed no letup in US-led military challenges to China’s expansionism in the South China Sea, while strong high-level US government support for the Philippines in the face of China’s latest coercive moves supported Manila’s unusually vocal protests against the Chinese actions. Beijing also had difficulty countering Biden’s strong emphasis on close collaboration with allies and partners, seen notably in the first QUAD summit resulting in a major initiative to provide 1 billion doses of COVID vaccines for Southeast Asia and nearby areas. The effectiveness of Chinese vaccines was now questioned by Chinese as well as foreign specialists and Beijing’s domestic demand was growing strongly, slowing donations and sales abroad.

China Emphasizes the Positive

Chinese leaders continued last year’s strong emphasis on China’s closer economic integration with Southeast Asian countries, notably through the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement, growing China-ASEAN trade and investment, financing with China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and Chinese support for regional countries in dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic. Supporting commentary stressed ever-closer Chinese integration with Southeast Asia through strengthened production chains and economic connections fostered by the BRI. Beijing highlighted the 7% growth in China-ASEAN trade in 2020, along with an increase in the first quarter of 2021 of 26% over the level in the first quarter of 2020. It advised that disruptions and declines in Chinese and Southeast Asian production chains involving the United States and the European Union prompted China and ASEAN to seek closer regional production chains and manufacturing collaboration. And it noted that China’s rapid economic rebound from the pandemic and Southeast Asia’s projected growth on over 5% in 2021 argued for more beneficial economic cooperation going forward.

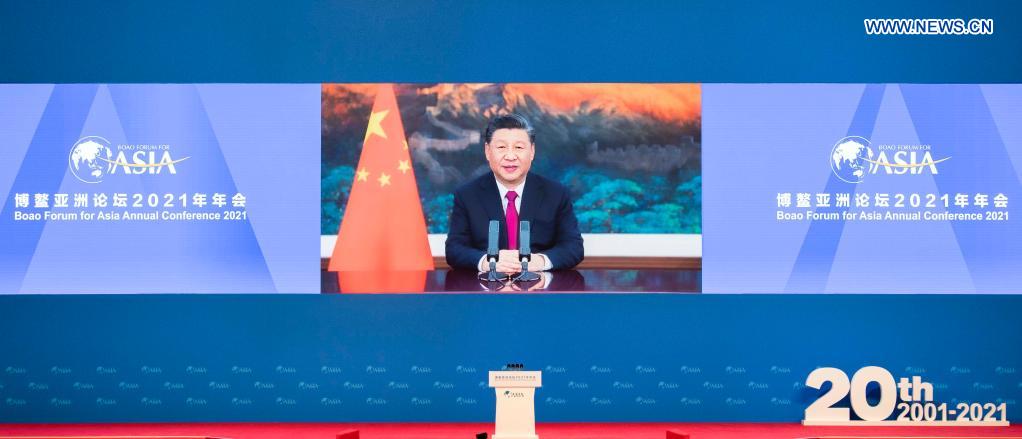

Figure 1 Chinese President Xi Jinping delivers a keynote speech via video at the Boao Forum for Asia Annual Conference. Photo: Xinhua/Li Tao

A capstone in this effort was the annual Boao Forum for Asia, hailed by Chinese media as the “largest on-site international forum” of 2021. This year’s forum attracted over 2,000 participants and over 1,000 journalists. The Chinese vice president attended in person, but President Xi Jinping and the 14 top-level foreign leaders participating did so via video link. President Xi’s address to the forum featured China’s vision for “high quality Belt and Road cooperation” with Southeast Asia and elsewhere. Xi implicitly countered prevailing criticism of the controversial Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as a collection of bilateral agreements giving Beijing strong leverage over individual states seeking financing and enabling corrupt, nontransparent deals often involving pollution and other environmental damage from coal fired electric power stations, hydropower dams and other infrastructure. Xi advised that the BRI was not a “private path owned by one single power” and Beijing sought “open, green, and clean” cooperation.

Problems for China in Southeast Asia received little attention during the annual meetings in March of the National People’s Congress (NPC) and the Chinese Peoples Political Consultative Conference. Premier Li Keqiang’s annual press conference after the NPC meeting did not address Southeast Asia. State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s responses to questions on Southeast Asia at his annual press conference at the NPC indicated that the China-ASEAN relationship was “a pace setter for regional cooperation,” with the two sides having a shared view on how to revitalize Asia and with China promising more support including vaccines to deal with the pandemic in Southeast Asia. Wang also emphasized “removing distractions and pressing ahead” in order to reach a conclusion of the protracted talks on a code of conduct in the South China Sea. The ASEAN chair representative announced in January that those talks probably will not conclude in 2021, citing the need for in-person consultations not possible under existing COVID requirements. Wang’s comments on Myanmar stressed Chinese calls for calm, restraint, dialogue, avoiding violence and easing the crisis as soon as possible.

China’s as Regional “Stabilizer”

That Beijing was concerned about possible adverse developments in Southeast Asia despite its avowed confidence in regional trends appeared in Wang’s very active diplomacy with Southeast Asia during this reporting period. Chinese and foreign reportage highlighted China shoring up its position amid continued acute rivalry with the United States. Wang traveled to the region for consultations in Myanmar, Indonesia, Brunei, and the Philippines in January, only three months after his visits in October 2020 to Cambodia, Malaysia, Laos, Thailand, and transiting Singapore. He followed up with individual meetings in Fujian province in April with visiting foreign ministers from Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines. According for foreign reports, the meetings were located outside Beijing as part of precautionary measures to avoid any resurgence of the pandemic in Beijing as the government prepared for the celebration of the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party in July. Beijing’s reporting on Wang’s talks with Southeast Asian counterparts related to the fight against COVID-19, economic revival after the pandemic, and guarding against outside power’s interference. On the latter, Chinese media emphasized Wang’s active diplomacy as part of China’s role as a regional “stabilizer,” in contrast with perceived intensified US effort in a vain attempt to enlist support from regional countries to “encircle” China.

The Myanmar Crisis

The February coup in Myanmar has upended political stability in the country, with its civilian leader Aung Sun Suu Kyi ousted by the military junta and a swift crackdown on anti-coup protestors that have left more than 760 people dead. China’s approach to Myanmar reflected careful diplomatic calibration with Southeast Asian leaders, while deflecting international concerns about excessive interference. Shortly after the coup in February, China blocked a UN Security Council statement condemning the military coup and warned that external pressure or sanctions would only worsen the delicate situation in Myanmar, though it later in March did back a Security Council statement that condemned “violence against peaceful protesters.” At a subsequent Security Council meeting in April, Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi emphasized his country’s support for ASEAN, and called for the regional organization to take an active role in Myanmar’s domestic reconciliation process and to deal with the junta directly. Wang’s message reflected key aspects of his discussion and consultation with counterparts from Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines in early April.

Figure 2 Chinese state councilor and foreign minister Wang Yi attends a United Nations Security Council high-level open debate. Photo: Xinhua/Liu Bin

On April 24, ASEAN convened an emergency session in Jakarta, with the leaders of Indonesia, Vietnam, Singapore, Malaysia, Cambodia, and Brunei in attendance, along with the foreign ministers of Laos, Thailand, and the Philippines. Myanmar’s Senior General Min Aung Hlaing was also in attendance. The meeting produced a regional consensus on five points, including an immediate cessation of violence, a constructive dialogue among all parties, a special ASEAN envoy to facilitate the dialogue, acceptance of aid, and a visit by the envoy to Myanmar. Although the formal statement at the end excluded a specific timeline for the release of political prisoners, the issue was raised and discussed in the deliberation. Malaysia Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin explained after the meeting that Myanmar “agreed that violence must stop” and “did not reject what was put forward by me and many other colleagues.” Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong added that “[Min Aung Hlaing] said he heard us, he would take the point in, which he considered helpful … He was not opposed to ASEAN playing a constructive role, or an ASEAN delegation visit, or humanitarian assistance.”

Following the summit, ASEAN has stepped up its diplomatic coordination to involve the United States and China to help enforce the commitments made and the consensus reached in the April 24 meeting. According to news reports, ASEAN has begun discussions with the two external powers for a foreign ministers’ meeting at the annual ASEAN Regional Forum to address ongoing challenges regarding the post-coup situation in Myanmar.

Gauging US-China Competition: The Quad and Vaccine Competition

The authoritative annual survey of opinion in Southeast Asia conducted by the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies reinforced recent studies charting China’s continued remarkable advancing political and strategic influence along with growing economic power in Southeast Asia. At the same time, the survey showed an even more remarkable high level of anxiety and distrust held by 88% of those polled about Beijing’s powerful regional position. Anticipating the new Biden administration, this year’s poll showed that the United States was viewed as more influential and trustworthy than in the previous year. Forecasting growing US-China rivalry, the survey marked a big increase in regional support for and trust in US strategic influence; if forced to choose, a strong majority, 61% (versus 52% in the previous poll) would choose the United States whereas those choosing China dropped from 46% last year to 38%.

The Biden administration’s strong promotion of the four-power (Australia, India, Japan, and United States) Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or Quad as a foundation of its pledged close engagement with allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific resulted in the first summit among the powers in March. This seemed to put the lie to Chinese discourse dismissing the Quad, with Foreign Minister Wang Yi forecasting in the past that “the headline grabbing idea would dissipate like sea foam.” And it was Beijing that appeared out of step with prevailing Chinese criticism of US initiatives as disruptive, out of step and unwelcome by Southeast Asian countries, when Quad powers announced how they would provide much needed COVID-19 vaccines to the region. US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan affirmed that “The Quad committed to delivering up to 1 billion doses to ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations), the Indo-Pacific and beyond by the end of 2022.”

Figure 3 Chinese vaccine maker Sinovac Biotech performs quality checks on their COVID-19 vaccine. Photo: Reuters/Nikkei Asia

China has repeatedly highlighted its role as the leading foreign source of vaccines for Southeast Asia, but those doses come with concerns about lack of transparency concerning clinical trials, safety, and true effectiveness. Such shortcomings were reinforced when the head of the Chinese Center for Disease Control told a conference in April that the efficacy of Chinese vaccines is “not high” and Beijing is considering options to “solve the problem.” Meanwhile, having controlled the pandemic in China through other means, Beijing lagged behind many countries in vaccinating Chinese citizens and in 2021 it launched stronger efforts to produce the vaccines needed for this massive exercise. As a result, foreign commentators reporting on lack of adequate capacity and production delays of Chinese vaccine makers predicted an increase in delays of promised Chinese vaccine shipments to Southeast Asian countries.

Against this backdrop, the Quad vaccine initiative, while also subject to possible delays, promised to go far in meeting pressing and protracted needs in Southeast Asian countries and thereby counter China’s current advantage. Experts forecast that only Singapore will achieve widespread vaccination this year. Some others will reach this goal in 2022 but Cambodia, Laos, Indonesia, Myanmar, and the Philippines will lag behind until 2023 or later.

South China Sea Complications and Disputes

Beijing’s self-proclaimed role as the regional stabilizer in Southeast Asia faced a serious complication as resolute US-backed opposition by the Philippines countered Beijing’s latest effort to use thinly disguised coercive expansion by Chinese security forces at the expense of other claimants to advance Beijing’s control in the South China Sea. The Biden administration’s top national security leaders worked effectively with their Philippines counterparts in employing repeated public protests and complaints, impressive demonstrations of military power and reaffirmations of alliance solidarity to thwart the latest episode of Chinese security forces intimidating advances at the expense of other claimants. Chinese officials were put on the defensive as the international spotlight on China’s strong-arm tactics starkly belied Beijing’s publicized beneficent image.

Figure 4 Chinese ships at the Whitsun Reef. Photo: Maxar Technologies/via Japan Times

The episode involved the massing of over 200 purported Chinese Maritime Militia ships in early March demonstrating overwhelming power to effectively occupy the disputed territory of Whitsun Reef. The reef is 175 miles from Philippines governed territory and within the Philippines’ Exclusive Economic Zone. The territory is also claimed by Vietnam. China’s claim rests on its expansive entitlement to most of the South China Sea that was deemed illegal by the UN Law of the Sea Tribunal in 2016. The Chinese ship presence was reported in a March 20 statement of the Philippines National Task Force for the West Philippine Sea, pledging government determination to monitor the situation and protect Philippine sovereignty. In the next week, Philippines Defense Minister Delfin Lorenzana issued a sharply worded demand that China recall the boats and halt this “provocative action of militarizing the area.” Philippines Navy and Coast Guard forces were deployed to the disputed area, and the foreign ministry filed a diplomatic protest. Even President Rodrigo Duterte, who has long played down South China Sea differences with China in the interest of improved economic and other relations with China, reportedly asserted the Philippines position in a meeting with the Chinese ambassador on March 25.

The Chinese Embassy in Manila, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokespersons and official commentary denied that the Chinese vessels were Maritime Militia saying they were fishing boats seeking shelter from bad weather and that the territory belonged to China. Research by Andrew Erickson and Ryan Martinson showed conclusively using automatic identification system transmissions that a number of People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia vessels were deployed at Whitsun Reef. And research by Zachary Haver showed Chinese authorities have invested heavily over the past decade to supply all fishing vessels in the South China Sea with communications equipment to be used for surveillance and in replacing older wooden boats with larger steel vessels at a pace approaching 100 a year. Chinese officials consider the fishing vessels as China’s “first line in defending China’s maritime rights and interests.”

Foreign governments weighed in with the US Embassy on March 23 accusing China of “using maritime militia to intimidate, provoke and threaten other nations.” Beginning a process of high-level US official involvement, National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan had a phone conversation with his Philippines counterpart emphasizing US support and the applicability of the US-Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty in the face of the recent “massing” of China’s “Peoples Armed Forces Maritime Militia vessels” at Whitsun Reef. Japan, Australia, Great Britain, Canada, and the European Union also sided with the Philippines in criticizing the Chinese flotilla as threatening regional peace.

Chinese vessels at Whitson Reef numbered about 180 in late March according to the Philippines Coast Guard. Defense Minister Lorenzana on April 1 said the number at the reef was now 44, but he warned strongly on April 2 that Chinese militia vessels were seeking to occupy more areas in the South China Sea. Philippines officials also disclosed that China had constructed structures in other parts of the Union Banks, a collection of reefs that includes Whitson Reef. In the following week, President Duterte’s legal counsel and the presidential spokesman released what were seen as unusually strong statements criticizing Chinese actions and defending Philippines sovereignty. The Foreign Ministry initiated a plan to issue a daily protest until the Chinese vessels left Whitson Reef.

Strong public US government support continued in April. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken had earlier tweeted firm US alliance support for the Philippines and followed on April 8 with a phone conversation with Philippines foreign minister opposing “the massing of PRC maritime militia vessels in the South China Sea, including Whitsun Reef.” He again affirmed the applicability of the US-Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty to the South China Sea. That day, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin had a similarly supportive phone conversation with Defense Minister Lorenzana.

By mid-April foreign reports said only “a handful” of Chinese vessels remained at Whitsun Reef, seemingly ending the standoff for now but noting why Beijing vacated now and whether or when the militia perhaps with Coast Guard or Navy support may return remained unknown. Against this background, President Duterte made his first public remarks on the controversy at a televised briefing on April 19, arguing against Philippines’ confrontation with China over the territorial dispute unless China was extracting oil from Philippines claimed territory. He stressed Philippines military weakness and added the judgment that the US will not come to the Philippines’ aid if the conflict is “of our own making.” On April 24, Philippines Coast Guard and related security forces began conducting widely publicized exercises in the disputed waters, prompting a Chinese complaint about Manila escalating tensions. The Philippines defense and foreign ministers rejected China’s opposition with the foreign minister using coarse language in demanding China withdraw its ships. Their tough public posture stood in contrast with Duterte’s remarks in late April that China was “a good friend” who would hopefully understand that the Philippines government had to protect its interests.

US, China Shows of Force, China’s Coast Guard Law

China viewed the Biden administration’s attentive resolve in support of the Philippines against the background of continued strong US military activism in the South China Sea that Beijing was determined to counter. The Beijing-based South China Sea Strategic Probing Initiative reported an unprecedented pace and intensity of US naval and air forces exercising in the South China Sea during 2020. Special attention focused on the two dual carrier strike group exercises held in July showing “very combat oriented” actions and nine freedom of navigation operations in 2020 challenging China’s South China Sea claims.

After brief slowdown in the sequence of Sino-American shows of force in the South China Sea in late 2020, the intensified pace of Sino-American military demonstrations in the South China Sea reemerged in 2021. In January Chinese forces carried out major South China Sea exercises. According to foreign reports, when a US carrier strike group was entering the South China Sea in late January, six Chinese H-6K heavy bombers flanked by four J-18 fighters flew into nearby Taiwan airspace with the pilots confirming orders for the simulated targeting and release of anti-ship missiles against the carrier. February brought another US dual carrier strike group exercise in the South China Sea as well as two US freedom of navigation exercises challenging Chinese South China Sea claims. March began with a Chinese announcement regarding a month of military exercises in the South China Sea. In early April a US carrier strike group and an accompanying amphibious assault ship group carried out exercises in the South China Sea followed a day later by the Chinese carrier Liaoning and accompanying warships entering the South China Sea after maneuvers near Taiwan.

On Jan. 22, China’s National People’s Congress passed a new Coast Guard law that went into effect in February. The law for the first time authorizes Chinese Coast Guard ships, long the mechanism of choice Beijing uses to intimidate and coerce South China Sea claimants, to fire on foreign vessels in “waters claimed by China.” According to Thayer Consultancy on Feb. 9, the Philippines voiced the strongest regional opposition to the law, filing a diplomatic protest calling it “a verbal threat of war to any country that defies the law.” Other Southeast Asian governments were publicly silent or offered less challenging responses. The US State Department warned that the law “strongly implies [it] can be used to intimidate the PRC’s maritime neighbors.” Referring to others’ opposition, the US statement said “The United States joins the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia, Japan, and other countries in expressing concern with China’s recently enacted Coast Guard law, which may escalate ongoing territorial and maritime disputes.”

Australia

Official Chinese media continued to counter Australian government officials seeking easing tensions and warned of protracted losses for Australia in ongoing Chinese actions restricting trade, tourism and student exchanges with Australia unless Canberra reversed recent policies adverse to Chinese interests. Adding to more than a dozen demands for changes in Australian policy made by Chinese diplomats in 2020, Beijing had a new target in April as the Australian federal government used a new national foreign relations law to end the Belt and Road agreements signed earlier between China and the Victoria state government. Beijing commentary registered dissatisfaction by repeatedly besmirching Australia as a racist society. It also widely publicized Australia’s differences with New Zealand, while wooing the latter with advantageous Chinese economic deals. In March, low-level Chinese commentary criticized Blinken’s strong public support for Australia in the face of “blatant economic coercion” from Beijing.

Regional Outlook

Regional diplomats anticipate that the ASEAN Regional Forum, typically convened in the summer, will be prepared to address the ongoing crisis in Myanmar. There will be greater Southeast Asian interest to solicit additional support from the United States and China to help enforce ASEAN’s earlier agreement and consensus plan with Myanmar’s military junta. It remains to be seen whether China’s diplomatic calibration with ASEAN of late on the issue will yield greater involvement by Beijing in the months ahead and whether the crisis would become an opportunity for closer regional coordination or a new source of conflict.

Jan. 12-16, 2021: Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi visits four Southeast Asian countries to kickstart the new year. In Myanmar, Wang discusses closer economic cooperation, including donations for vaccines and medical supplies, border security, and China’s role in brokering peace with Myanmar’s ethnic armed groups. In Indonesia, Wang and his counterpart discuss bilateral cooperation on trade and investment, as well as closer coordination to stem the global pandemic.

Jan. 15, 2021: In Brunei, the third leg of his regional tour, Wang’s visit marks the 30th anniversary of bilateral ties, and the two countries pledge to work together through ASEAN, where Brunei is the rotating chair for 2021.

Jan. 16, 2021: In the Philippines, Wang announces that his government will donate half a million doses of COVID-19 vaccines to Manila. Among other highlights, the two sides also agree to deepen infrastructure development.

Jan. 22, 2021: China announces the passage of a new law that authorizes its Coast Guard vessels to fire on foreign ships and to destroy other countries’ structures on islands in waters claimed by China, including in the disputed areas of the South China Sea. The new law prompts the Philippine foreign minister to lodge a diplomatic protest against China.

Jan. 26, 2021: Brunei indicates that the long-awaited Code of Conduct (COC) in the South China Sea may not be concluded in 2021, owing to continued difficulties for convening in-person negotiations and deliberations amidst the pandemic. Chinese Premier Li Keqiang had set initially a three-year timeline to conclude the COC with ASEAN in 2018. 2021 was supposed to the year where regional negotiators begin their final reading of the text.

Feb. 28, 2021: China’s Maritime Safety Administration announces that the country will hold military exercises in the South China Sea throughout March 2021.

March 7, 2021: Chinese maritime militia vessels are spotted in the Whitsun Reef in the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone, prompting the Philippines to lodge a diplomatic protest against China for the incursion.

March 8, 2021: Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi discusses key foreign policy issues at his annual press conference at the National People’s Congress. On China’s relations with Southeast Asia, Wang emphasizes the positive aspects of regional economic and security cooperation.

March 20, 2021: In response to the continuing presence of Chinese vessels in the Whitsun Reef, the Philippines National Task Force for the West Philippine Sea pledges that Manila will continue to monitor the situation and protect the country’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.

March 30-April 2, 2021: Visiting foreign ministers from Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines meet one-on-one with Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi in Nanping, a city in the southern province of Fujian. The bilateral meetings focus on the latest situation in Myanmar. China indicates its support for ASEAN to take the lead in managing the post-coup crisis in Myanmar.

April 18-21, 2021: China hosts the annual Boao Forum for Asia. With over 3,000 participants in attendance, the forum marks one of the largest international gatherings in 2021. Chinese President Xi Jinping’s message at this year’s forum focuses on the Belt and Road Initiative, a signature program linking regional economies, and the importance of global economic governance.

April 19, 2021: China expresses concern with the ongoing unrest in Myanmar but rejects a UN Security Council resolution condemning the military coup. Instead, China supports regional efforts spearheaded by ASEAN to take a central role in working directly with the junta.

April 24, 2021: ASEAN leaders meet in Jakarta and issue a five-point consensus with regard to the post-coup situation in Myanmar. The regional consensus calls for an immediate cessation of violence and a visit by an ASEAN envoy, among other priorities. ASEAN begins laying the groundwork for a foreign ministers’ meeting with the United States and China under the ASEAN Regional Forum framework to enforce the consensus plan agreed to earlier.