Articles

The summer of 2021 may be the best and worst time for Russia-China relations. There was much to celebrate as the two powers moved into the third decade of stable and friendly relations, symbolized by the 20th anniversary of both the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and the “friendship treaty” (The Treaty of Good-Neighborliness and Friendly Cooperation Between the People’s Republic of China and the Russian Federation). This historical moment, however, paralleled a hasty and chaotic end to the 20-year US interlude in Afghanistan with at least two unpleasant consequences for Beijing and Moscow: a war-torn Afghanistan in their backyard with an uncertain future and worse, a United States now ready to exclusively focus on the two large Eurasian powers 30 years after the end of the Cold War. As the Afghan endgame rapidly unfolded in August, both sides were conducting large exercises across and around Eurasia. While Afghanistan may not again serve as the “graveyard of empires” in the 21st century, the end of the US engagement there will usher in an era of competition, if not clashes, between rival empires.

Friendship Treaty 20 Years After

On June 28, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping held a video conference, reaffirming their “best-ever” ties. Their chief concern was extending the China-Russia “friendship treaty” for another five years. Relations between Russia and China “set an example for the formation of a new type of international relations,” said Xi. Putin noted that the treaty elevated bilateral relations to “an unprecedented height and … make them an example of 21st-century interstate cooperation.”

A joint statement was released for the 20th anniversary of the friendship treaty, which has anchored post-Soviet Russia-China relations in the key areas of border stability, noninterference in domestic politics, nuclear strategy (non-first use of nuclear weapons against each other and not targeting nuclear weapons against each other), etc. The statement summarized the 20-years of experience of the relationship and mapped future tasks. The current relationship between Moscow and Beijing is “mature, constructive and sustainable … representing a model of harmonious coexistence of the States and mutually beneficial cooperation between them.” The statement dismissed the view that the two are moving toward a Cold War-style military alliance yet insisted that current relations “exceed” alliance by being non-opportunistic, non-ideological, non-interfering, self-sufficient, and not directed against third countries. The border issue was “completely resolved” and the two countries “have no mutual territorial claims,” and “Russia is interested in a stable and prosperous China and China is interested in a strong and successful Russia.”

The document dealt with various aspects of bilateral ties: economics (part 5), integration of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and Russia’s Greater Eurasian Partnership (part 6), and societal exchanges (part 7). More than half the 5,800-word document (in the Chinese version) is devoted to global affairs. In contrast, the original friendship treaty in 2001 was under 3,000 words, mostly covering bilateral issues. Twenty years later, the Xi-Putin statement covers a much wider range of global issues, including non-interference in internal affairs, the role of the UN and WTO, public health, nuclear weapons, outer space, chemical-biological weapons conventions, cybersecurity, terrorism, multilateralism, and more. “As global turbulence intensifies, the relevance of Russian-Chinese strategic cooperation increases,” said the statement. Specifically, the document notes the mutual support of each other’s foreign policy goals: China’s “community of shared future for humanity” and Russia’s “fair multipolar system of international relations.”

For Russian and Chinese political elites, the focus on global affairs in the joint statement reflects a much-changed world since it was signed 20 years ago. Less than two months after the signing of the friendship treaty on July 16, 2001, the world was forever changed by the 9/11 attacks, leading to the US intrusion into Central Asia. Both Putin and then-Chinese President Jiang Zemin pledged support, ahead of any US allies, for US counterterror operations. Fast forward to 2017, China and Russia found themselves atop the list of US strategic competitors, ahead of threats like North Korea, Iran, and other transnational terrorist groups, according to Trump’s first National Security Strategy.

Given the changes and fluidity in their strategic environment, the 2021 statement of the China-Russia friendship treaty reflects an enhanced mutual desire for closer coordination in foreign and security policies. Interestingly, military cooperation (part 4) was prioritized ahead of other functional areas and the two militaries will increase the frequency and scope of their joint exercises and exchanges.

Throughout the past few months, senior diplomats interfaced on various occasions, including two meetings of defense ministers. In late May, Moscow hosted the 16th China-Russia strategic security consultation, co-chaired by Nikolai Patrushev, secretary of the Russian Security Council, and Yang Jiechi, member of the Communist Party Politburo. The two “had an in-depth exchange of views and reached broad consensus on China-Russia relations and a number of major issues regarding global security and strategic stability,” noted Xinhua.

Putin, who was in Sochi, talked to Yang over the phone. “Russia is firmly committed to developing the comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination with China at a high level and is willing to strengthen strategic coordination between the two countries,” said the Russian president.

Putin’s call was two days after a video conference with Xi on May 19. The two heads of state presided over, via videoconference, a ceremony to launch the construction of four nuclear power units (the seventh and eighth power units at the Tianwan NPP and the third and fourth power units at the Xudapu NPP) in China with a total contract of $3.6 billion. COVID did not seriously delay these multi-billion-dollar energy projects. Once operational, these power units would produce 37.6 billion kWh per year, equivalent to an annual reduction of 31 million tons of CO2 emissions.

As the summer continued, the Taliban’s stunning takeover of Afghanistan produced a huge uncertainty for regional stability. On Aug. 25, Putin and Xi had “an in-depth telephone conversation on the Afghan problem,” and agreed to use the SCO “as much as possible” for regional security.

SCO’s 20th Anniversary

June was the SCO’s 20th anniversary. In his video speech to the reception in Beijing on June 15, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi noted that the regional group had blazed a cooperation and development path that suits regional conditions and meets the needs of all parties. He also called for joint efforts in the areas of economy, security, public health, societal exchanges to accelerate the building of “a community with a shared future.”

Originally set up in 1996 as the “Shanghai Five” (China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Russia) for post-Soviet border security management, the informal forum added Uzbekistan in 2001 and morphed into the SCO with an expanded mission of regional security with an explicit goal of combating terrorism, separatism, and extremism. In the post-9/11 decades, the SCO weathered geostrategic changes (the huge US presence in and around Afghanistan), domestic disturbances (“color revolutions,” et al), and the diverse political, cultural, and economic backgrounds of its members. The SCO gradually expanded its cooperation in security (military exercises) and economic functions (China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union). With a headquarters in Beijing and a Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure (RATS) in Tashkent of Uzbekistan, the SCO added India and Pakistan as full member-states in 2017, along with four observer states (Afghanistan, Belarus, Iran, and Mongolia) and six dialogue partners (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Cambodia, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Turkey).

At its 20th anniversary, the SCO remains a viable regional forum despite the COVID hindrance. April-August saw numerous SCO activities in foreign policy, finance, security, hi-tech parks, transportation, industry, science and technology, tourism, law enforcement, environment, anti-drug, agriculture, public health, sports, women, think tanks, youth, media, etc. The annual foreign ministerial meeting in Dushanbe, Tajikstan on July 14 agreed to grant the status of dialogue partner to Egypt and Saudi Arabia, to be finalized in the September SCO summit. SCO member states already covered more than 70% of the Eurasian landmass and about 50% of the world’s population. Dialogue partner status is the first step toward full membership. In Dushanbe, Foreign Minister Wang Yi made several proposals for the SCO’s development by closer coordination in security, public health, development, and foreign policy.

There was, however, little mood for celebration at the SCO’s 20th anniversary. As the endgame in Afghanistan accelerated, developments there dominated the annual foreign minister gathering. After a meeting with Afghan Foreign Minister Mohammad Haneef Atmar as part of the SCO-Afghanistan Contact Group, a joint statement was issued, calling for peace and stability in the war-torn country. “We believe that reaching an early settlement in Afghanistan is a major factor in maintaining and strengthening security and stability in the SCO space. “We confirm the position of the SCO members that the conflict in Afghanistan can only be settled by political dialogue and an inclusive peace process conducted and led by the Afghans themselves,” the statement added.

The SCO’s statement, however, could hardly keep pace with events on the ground.

The Afghan Endgame

Despite deepening geopolitical rivalry between China, Russia, and the US, Afghanistan remained a rare case of overlapping interests among the three powers, hoping for a soft-landing. Since 2019, they had worked together in the format of an extended “Troika” group for a peaceful settlement in Afghanistan. For Moscow and Beijing, the US military footprint in Afghanistan was regarded as a geopolitical threat but also a useful cap on Islamic militancy in their “backyard.” Both hoped for a US departure only after a sustainable and peaceful deal between various players in and out of Afghanistan so that the country would not become a terrorist safe haven again.

Beijing and Moscow were taken back by the speed and style of the Afghan endgame. On May 11, US forces left the massive Kandahar Airfield without informing the Afghan side. On July 5, Bagram Airfield 60 km north of Kabul was vacated in the same manner. On Aug. 15, Afghan President Ghani fled Kabul as Taliban forces took over the capital. China and Russia have no option but to live with an Afghanistan with an unclear political future. Their approaches to the Afghan issue, however, were quite different, as China was more actively engaging different players both inside and outside Afghanistan.

Wang, speaking to the 2nd C+C5 foreign ministerial meeting (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan + China) in the Chinese city Xi’an on May 11, warned that “foreign troops should withdraw from Afghanistan in an orderly and responsible manner to prevent any hasty action from adversely affecting and seriously interfering with the peace and reconciliation process in Afghanistan.” It was unclear if Wang was aware that US forces were in the process of completely leaving the Kandahar Airfield. A few days later, the Chinese foreign minister informed his Afghan counterpart that China “is willing to host intra-Afghan talks and help the anti-terrorism effort.” Wang repeated the offer in mid-July during the SCO foreign ministerial meeting in Dushanbe.

While intensifying diplomatic activities regarding Afghanistan, China was perhaps the first to urge (on June 19) that its citizens leave the country as early as possible via commercial flights. It was against this backdrop that Wang paid an official visit to the frontline country of Tajikstan on July 14 before joining the SCO foreign ministerial meeting in Dushanbe and a meeting with Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov the following day in Tashkent. This was followed by Xi’s telephone talk to Afghan President Ghani on July 16. Xi urged an “Afghan-led and Afghan-owned political dialogue for national reconciliation and peace process.” He also promised more assistance for fighting against COVID and hoped for more protection of Chinese citizens and organizations in Afghanistan.

Xi’s talk with Ghani came 10 days after the sudden departure of US forces from Bagram Airfield and a new deadline for full US troop withdrawal to Aug. 31, leading to the collapse of the Afghan Army across the country from late July. On July 28, Wang met with Taliban political chief Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar in north China’s Tianjin. “The sudden withdrawal of forces by the United States and NATO from Afghanistan marks the failure of the United States’ Afghanistan policy, and Afghan people now face an important opportunity to stabilize and develop their own country,” Wang told the Taliban chief.

Figure 1 Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi meets with Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, political chief of Afghanistan’s Taliban, in north China’s Tianjin, July 28, 2021. Photo: Xinhua/Li Ran

Baradar hoped that China would be more involved in Afghanistan’s peace and reconstruction process, and play a bigger role in the country’s reconstruction and economic development. Wang stated that the Taliban should draw a clear line from the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM) and other terrorist groups. In reply, Baradar promised that the Afghan Taliban would “absolutely not allow any forces to do anything harmful to China in Afghanistan’s territory.”

The Baradar visit was not the first Taliban group to travel to China. There were contacts between the Taliban and China before 9/11, which had been suspended for a few years when China supported the Northern Alliance in the aftermath of Sept. 11. China, however, has never defined the Taliban as a terrorist group. As the moderate faction of the Taliban stopped supporting the East Turkestan Islamic Movement, Taliban members “routinely” visited China, according to Chinese sources. The Tianjin meeting was the first publicized visit.

China’s proactive diplomacy was driven by both security (Xinjiang) and economic (all Afghan neighbors are BRI-related countries) interests. The two are integrated. This was the case in the terrorist bombing on July 14, killing nine Chinese workers bussed to the Dasu Hydropower Project in Pakistan’s northwestern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, which is part of China’s BRI activity in Pakistan.

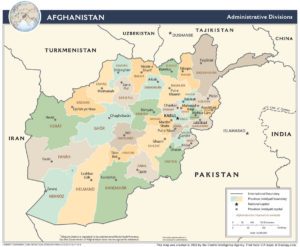

Figure 2 The 92-km China-Afghan border is shown on the upper right corner of the map. Photo: CIA

Beyond the BRI, China, as an Afghan neighbor, is connected with the war-torn country by a 92-km border at the eastern tip of the 300-km Wakhan valley. China reportedly provided $70 million in military aid to Afghanistan in 2016-18 and helped the Afghan military create a mountain brigade in the corridor specifically for anti-terror purposes. Beyond that, China has had inputs into Afghanistan during the 20-year US occupation, including billions of dollars in economic assistance, assorted projects such as schools, hospitals, and apartments, as well as food assistance and the training of thousands of Afghan students and technical personnel both in China and Afghanistan. Since 2017, China, Afghanistan, and Pakistan have discussed the possibility of extending the China-Pakistan economic corridor to Afghanistan. Meanwhile, some large economic projects—the $4 billion contract of the Anyak copper mine in 2008 and the 2011 contract for the Amu Darya Basin oil and gas field—remain idled due to security concerns.

Unlike China, Russia continued, from February 2003, to regard the Taliban as a terrorist group. That, however, did not stop Russia from engaging them. “We are talking with all the more or less significant political forces in Afghanistan: both with the government and with the Taliban and with the representatives of Uzbeks, Tajiks, with everyone,” noted Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov on Aug. 13. In fact, Taliban representatives visited Moscow as early as November 2018 for a Russia-sponsored “peace conference.” They also did so twice in 2021 (March 18 and July 8) to attend the Troika consultations, apparently a favorite platform for Russia. Two days before the Taliban takeover of Kabul, Lavrov envisioned an expanded Troika including Iran and India, in addition to Pakistan. Beyond Afghanistan, Russia has invested significant resources in Central Asia, where it holds considerable sway in the security area (Collective Security Treaty Organization, CSTO; and the Commonwealth of Independent States, CIS).

Developments in Afghanistan complicated broader relations with the US as Lavrov and Blinken met on May 19 in Reykjavik to prepare for Biden-Putin talks in mid-June. For the Kremlin, the Afghan issue should be handled in light of relations with Washington. Russia has traveled a long way from its strategic decision to allow its Central Asian allies to host US forces (Uzbekistan’s Karshi-Khanabad base, closed in 2005; and Kyrgyzstan’s Manas base, closed in 2014) and its own contribution to the NATO operations in Afghanistan via the Northern Distribution Network (2009-2015). With the end of the US military footprint in Afghanistan, however, Russian officials publicly dismissed the possibility of hosting US forces in CSTO states. Instead, Russia chose to reinforce its military base in Tajikistan in late July and conducted an exercise on Aug. 5-10 with Tajik and Uzbek forces in Tajikistan just 12 miles from the Afghan border.

China, too, activated its security mechanism with Tajikistan. On Aug. 18-19, Chinese and Tajik internal security forces ran an exercise code-named “Anti-terror Coordination-2021” in Dushanbe. Meanwhile, China and Russia ruled out any possibility of direct military intervention into Afghanistan. On July 28, Russian and Chinese defense ministers met on the sideline of the SCO annual defense ministers meeting in Dushanbe, which focused on the Afghan issue. In September, SCO will run its “Peace Mission-2021” anti-terror exercises in Russia’s Central Military District.

In the UN, Russia and China coordinated to abstain from voting on a US-sponsored Afghanistan resolution on Aug. 30calling on the Taliban to allow safe passage for those seeking to leave Afghanistan. While Chinese UN envoy Geng Shuang said the US and its allies left behind a “huge catastrophe while shifting the blame and responsibility to Afghans’ neighboring countries,” Russian Ambassador Vassily Nebenzia complained that the resolution failed to incorporate Russia’s concerns about the “brain drain” effect of evacuating Afghans and didn’t address the issue of US freezing the Afghan government’s US accounts.

Russian and Chinese abstention in the UN votes left the door open for future UN roles in Afghanistan. China’s official media Xinhua, for example, did not mention Chinese and Russian abstention. Three days before the UN resolution, the Chinese Defense Ministry announced that China will hold its first multinational peacekeeping live exercise, “Shared Destiny-2021,” on Sept. 6-15 in central China. More than 1,000 troops from China, Pakistan, Mongolia, and Thailand will join the drill. According to an agreement, the UN could authorize the SCO to dispatch peacekeepers on UN’s behalf.

“The Guns of August”

Meanwhile, two large war games unfolded around and across Eurasia. On Aug. 2-27, the US military conducted Large Scale Global Exercise 21 (LSGE21), the largest in 40 years. The 25-day drill involved some 25,000 participants from all US services alongside allies (UK, Australia, and Japan) across 17 time zones with a scenario of simultaneously countering Russia and China. Throughout the summer, the US’s European and Asian allies expanded their footprint in the South China Sea (SCS). A day before LSGE21 ended, the Malabar maritime exercises, which began in 1992 as a joint US-India drill, kicked off its 2021 phase in the Philippines Sea with a full Quad formation (US, India, Australia, and Japan) for the first time. To offset the growing maritime activities of the US and its allies, China launched its own large naval drills in August in SCS and other locations as a “pointed warning” to the US.

Figure 3 The United Kingdom’s Carrier Strike Group (CSG 21) and USS America Expeditionary Strike Group (AMA ESG,” with the 31st Marine Expeditionary Unit, launch advanced international aviation missions in support of Large-Scale Global Exercise (LSGE) 21, Aug. 20. Photo: Royal Navy

August was also the month for a China-Russian joint “strategic” military exercise code-named “West·Coordination-2021” (“西部·联合-2021”) in northwestern China with a declared goal of “joint safeguarding regional security and stability (联合维护地区安全稳定). More than 13,000 troops participated with more than 400 pieces of equipment, including China’s J-20 stealth fighters, for the first time, alongside China’s H-6, H-7A, J-16, J-11 bombers and fighters, as well as five Russian Su-30SMs. The drill was conducted by a joint headquarter and integrated units for a higher level of interoperability.

Military exercises have become routine between the two large Eurasian powers. Those “strategic” ones, however, are relatively new. They are usually conducted in more conventional style with heavy artillery, armor, and air components, to distinguish them from the “lite” version “anti-terror” drills within the SCO framework. In 2018-20, China participated in three strategic exercises in Russia (Vostok-2018, Tsentr-2019, and Kavkaz-2020) when thousands of Chinese troops traveled to Russia. “West·Coordination-2021” was the first of this kind held in China. Russian Defense Minister Shoigu observed the live phase of the drill.

Figure 4 China-Russia “West·Coordination-2021” exercises, August 9-13, 2021 in northwestern China. Photo: Vadim Savitsky/Russian Defence Ministry Press Office/TASS

Until recently, interoperability between Russian and Chinese units was relatively low, partially due to language barriers. During the “West·Coordination-2021” exercises, a command-control digital system developed exclusively for joint operations of the two militaries (专门的中俄联合指挥控制系统) was used for the first time, which significantly enhanced interoperability at all levels, according to a Chinese account. As a result, various specialized PLA units (engineers, logistics, etc.) were directly embedded in Russia’s mechanized assault groups. The PLA infantry units also chose the occasion to let the Russians operate their equipment with an extraordinary level of transparency. For this, a Russian motorized infantry regiment arrived in China two weeks before the live drill and spent considerable time practicing Chinese equipment.

As the maritime (US) and continental (Russia and China) giants were rehearsing for the perceived worst scenario in August, the end of the 20-year occupation of Afghanistan promises no silencing of guns either inside the war-torn nation or around the globe. In this regard, the historical analogy, or cliché, that Afghanistan was the “Graveyard of Empires,” is misplaced. The final US exit from Afghanistan—no matter how “untidy” it was, to borrow Donald Rumsfeld’s famous phrase for the mismanaged Iraq occupation—was considered imperative for a more China-and-Russia-focused strategy, as President Biden noted in his Aug. 31 speech.

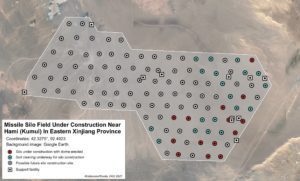

Figure 5 The Hami missile silo field covers an area of about 800 sq km and is in the early phases of construction. Photo: Federation of American Scientists

As if the August heat, and hostility, were not enough, Western media was taken back by the newly discovered construction of 350 ICBM silos in China’s northwest. Beijing has not publicly dismissed the revelation. The Washington Post went as far as to speculate that China wanted “to be caught.” The fixed silo sites, more likely for China’s solid-fuel DF-31or DF-41 ICBMs, would help reduce the threat from drones and cruise missiles against China’s current mobile ICBM launchers. Moreover, they would give China a launch-on-warning capability, allowing China to retain its no-first-use policy while ensuring the survivability of its nuclear forces, noted an RT analyst. China would easily increase its nuclear warheads to 1,000, given the 10-warhead payload on each DF-31 or DF-41. This is a level of more credible deterrence that China could do with relative ease, as some Chinese media had long advocated.

Even if China increases its nuclear warheads to 1,000, its nuclear arsenal is considerably smaller than that of the US (6,257) and Russia (5,550). For Adm. Charles Richard, commander of US Strategic Command, collaboration between China and Russia is more threatening than “China’s strategic breakout.” “Both Russia and China have the ability to unilaterally, at their own choosing, go to any level of violence, to go to any domain to go worldwide, with all instruments of national power,” Richard said on Aug. 30 at the Hudson Institute, noting that if they work in tandem, it would be even worse.

Richard’s concern about a Moscow-Beijing alliance sharply contrasted with the “reluctance” to move toward an alliance in China and Russia. A newly released annual “China-Russian Dialogue: 2021 Mode,” penned by Fudan University in Shanghai and Russia’s International Affairs Council, dismisses US obsession with the alliance issue as a conceptual trap and opts for a more flexible, pragmatic, and comfortable mode of reciprocity.

An example: in late July, as a purely bureaucratic move, the Russian government submitted to the State Duma an agreement on extending, for another 10 years, the mutual notification for launches of ballistic missiles and carrier rockets. It was signed by Russian and Chinese defense ministers on Dec. 15, 2020, anchoring the strategic security issue in a trust-and-verified and reciprocal mechanism regardless of the size of each country’s nuclear forces.

Conclusion: Anniversary Plight

By the end of summer, all these anniversaries—20th for the SCO, China-Russia friendship treaty, and the US’s Afghan war; 30th for the Soviet breakup—means little, be they commemorated or overlooked. The world seems to be moving steadily toward an increasingly hostile round of great power games.

For Henry Kissinger, whose China breakthrough occurred 50 years ago (July 9), a US-China war “will be an unspeakable catastrophe.” The Kissingerian “catastrophe,” however, won’t be another Cold War, which turned out to be “a long peace” between two ideological rivals of Western descent (Western liberalism vs Western Marxism). Nor will it be a “total war” like World War I as Kissinger frequently warned in the past two years. In fact, the last time the world endured a pandemic on the scale of COVID-19—the 1918-20 “Spanish flu” pandemic—some academics suggest its sheer lethality ironically helped silence the guns of World War I.

Now, in the 21st century, a pandemic is pushing the great powers further apart. The world is in uncharted waters, for better or worse.

May 12, 2021: Chinese city Xi’an hosts second C+C5 foreign ministers’ meeting of China and five Central Asian countries—Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. They focus on Afghanistan.

May 19, 2021: Russian and Chinese presidents take part, via videoconference, in a ceremony to launch the construction of four nuclear power units at the Tianwan NPP and the Xudapu NPP in China.

May 21, 2021: Chinese Minister of Science and Technology Wang Zhigang meets Russian Ambassador to China Andrey Denisov in Beijing.

May 25, 2021: 16th China-Russia strategic security consultation is held in Moscow and co-chaired by Nikolai Patrushev, secretary of the Russian Security Council, and Yang Jiechi, member of the CPC Politburo. Russian President Putin, in Sochi, talked to Yang over the phone.

May 27, 2021: SCO holds online meeting of experts to prepare for the first meeting of Security Council Secretaries in Tashkent.

June 1, 2021: BRICS foreign ministers hold annual videoconference under India’s chairmanship. COVID and economic development top the agenda, while Afghanistan was the 22nd of 35 items in the “media statement” issued by the ministers.

June 1, 2021: Chinese and Russian foreign ministers Lavrov and Wang Yi speak via video to the 6th InternationalConference Russia and China: Cooperation in a New Era.

June 4, 2021: FM Wang Yi talks to Russian counterpart Lavrov over the phone. They discussed bilateral and international issues.

June 15, 2021: FM Wang gives a speech via video to reception for 20th anniversary of the SCO.

June 15, 2021: Liu Xiaoming, special representative of the Chinese Government on Korean Peninsula Affairs, meets Russian Ambassador to China Andrey Denisov in Beijing.

June 19, 2021: Chinese Embassy in Kabul urges Chinese citizens to leave the country ASAP via commercial flights.

June 21, 2021: Russia’s new ambassador to Washington, Anatoly Antonov, briefs outgoing Chinese Ambassador Cui Tiankai on Putin-Biden talks in Geneva on June 16. Antonov tells reporters that “nobody can divide Russia and China.”

June 28, 2021: President Xi Jinping and Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin hold video conference for 20th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Good-Neighborliness and Friendly Cooperation Between the People’s Republic of China and the Russian Federation.

July 8, 2021: Xi sends condolences to Putin after the crash of a Russian commercial airplane.

July 14, 2021: SCO holds annual foreign ministerial meeting in Dushanbe, Tajikstan. Saudi Arabia and Egypt are accepted as SCO’s dialogue partners to be finalized by the SCO summit in September. A joint statement in the name of “the SCO-Afghanistan Contact Group” was issued, calling for peace and stability in the war-torn South Asian country.

July 14, 2021: A suicide attack kills 13 people, including nine Chinese workers who were bussed to the Dasu Hydropower Project in Pakistan’s northwestern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. The bombing was carried out by Islamist militants and backed by the Indian and Afghan intelligence agencies says Pakistani Foreign Minister Shah Mehmood Qureshi.

July 15, 2021: Wang meets with Lavrov in Tashkent on the sidelines of the high-level international conference “Central and South Asia: Regional Connectivity. Challenges and Opportunities.” The two top diplomats focused on the Afghan issue.

July 16, 2021: Xi talks with Afghan President Ghani over the telephone.

July 21, 2021: Putin sends a message to Xi, expressing deep condolences over the tragic consequences of the extensive flooding in the province of Henan.

July 27, 2021: Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova writes on her webpage that the assassination of Haiti President Jovenel Moïse was related to Taiwan.

July 28, 2021: SCO defense ministers hold their annual meeting in Dushanbe, Tajikistan.

July 28, 2021: FM Wang meets Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, political chief of Afghanistan’s Taliban.

Aug. 5-10, 2021: Russian, Tajik, and Uzbek forces conduct an exercise in the Kharb-Maidon drilling field in Tajikistan just 12 miles from the Tajik-Afghan border.

Aug. 9-13, 2021: China and Russia conduct strategic exercise “West·Coordination-2021” in northwestern China.

Aug. 16, 2021: Lavrov initiates a telephone conversation with Wang. They talk about Afghan and COVID issues.

Aug. 18-19, 2021: Chinese and Tajik internal security forces run the joint “Anti-terror Coordination-2021” in Dushanbe.

Aug. 25, 2021: Xi holds a phone conversation with Putin, having an“ in-depth discussion on the Afghanistan problem … in a traditionally friendly and trust-based atmosphere.”

Aug. 26, 2021: China’s Defense Ministry announces that China will hold its first multinational peacekeeping live exercise, “Shared Destiny-2021,” in central China with roughly 1,000 troops from China, Pakistan, Mongolia, and Thailand joining.

Aug. 30, 2021: Russia and China cast abstention vote in UN regarding the US-sponsored Afghan resolution calling on the Taliban to allow safe passage for those seeking to leave Afghanistan.