Articles

Perhaps more than any month in history, February 2022 will come to symbolize how the states of peace and war can flip-flop in a few days, with dire consequences for the global order. On Feb. 21, just one day after the closing ceremony of the Beijing Winter Olympics, Russia announced its official recognition of the independence of the two breakaway regions (Donetsk and Luhansk) of Ukraine. Three days later, Russia launched its “special military operation” in Ukraine to end the “total dominance” and “reckless expansion” of the United States on the world stage (in the words of Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov). As the West imposed sanctions on Russia and rushed arms into Ukraine, China carefully navigated between the warring parties with its independent posture of impartiality.

Russia’s Fog of War

Russia’s “special military operation” was a surprise to China. “Had China known about the imminent crisis, we would have tried our best to prevent it,” said Qin Gang, China’s ambassador to Washington. Qin’s expressed intention to influence Russia’s Ukraine policy would have been unlikely to be effective given the highly centralized foreign policymaking mechanism in Vladimir Putin’s Russia and NATO’s consistent move eastward. In the fog of war of words immediately before the Russian invasion, both Russia and Ukraine repeatedly dismissed the possibility of war despite the US’ insistence that conflict was imminent. In retrospect, Beijing seemed inclined to trust “insiders” (Ukraine and Russia) while dismissing US “warnings” as premature and even disinformation. As a result, China did not begin to evacuate its citizens (about 6,000 of them) from Ukraine until after Russia’s invasion started.

Moscow moved quickly to fill the information gap with Beijing. Within the first few hours of the invasion, Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov called his Chinese counterpart Wang Yi and said Russia’s military actions were the consequence of the “broken” commitment by the US’ and NATO’s expansion. Russia, therefore, was “forced” to take necessary measures to safeguard its own rights and interests, Lavrov added.

Wang’s brief response conveyed three points: 1) China has always respected the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all countries; 2) China recognized the complex and special historical context of the Ukraine issue and that Russia’s security concerns were legitimate; and 3) a balanced, effective, and sustainable European security mechanism should be established through dialogue and negotiation. While the first two points appealed to the warring parties, the third spelled out the China-preferred approaches to conflict resolution and final goals.

Putin and Xi conversed over the phone the following day. It was unclear which side initiated the call. Putin gave Xi “a detailed account of the reasons” behind Russian actions. Putin also told Xi that Russia was ready to send a delegation to Minsk for talks with Ukraine. Xi responded by saying that China supported efforts to resolve the Ukraine crisis via dialogue. The Chinese side believed that it received a positive response.

In his teleconferences with top European diplomats on Feb. 26, Wang Yi reiterated his three principles on the Ukraine conflict while adding two additional points: the Ukraine conflict was “something China did not want to see,” and the UN Security Council should play a constructive role in resolving the Ukraine issue. These five points constituted the core of China’s policies in the conflict.

Beijing’s quick moves in the first three days of the Ukraine conflict meant to define the parameters of its policy toward the warring sides. It was a sensitive and difficult endeavor given the cumulative pressure raised by all sides prior to Russia’s invasion. In this regard, Wang Yi’s note (the Ukraine conflict was “something China did not want to see”) was genuine for at least two purposes: it said to the West/US that Beijing had no role in making the conflict, and it told Russia that its use of force was not a preferred option for China.

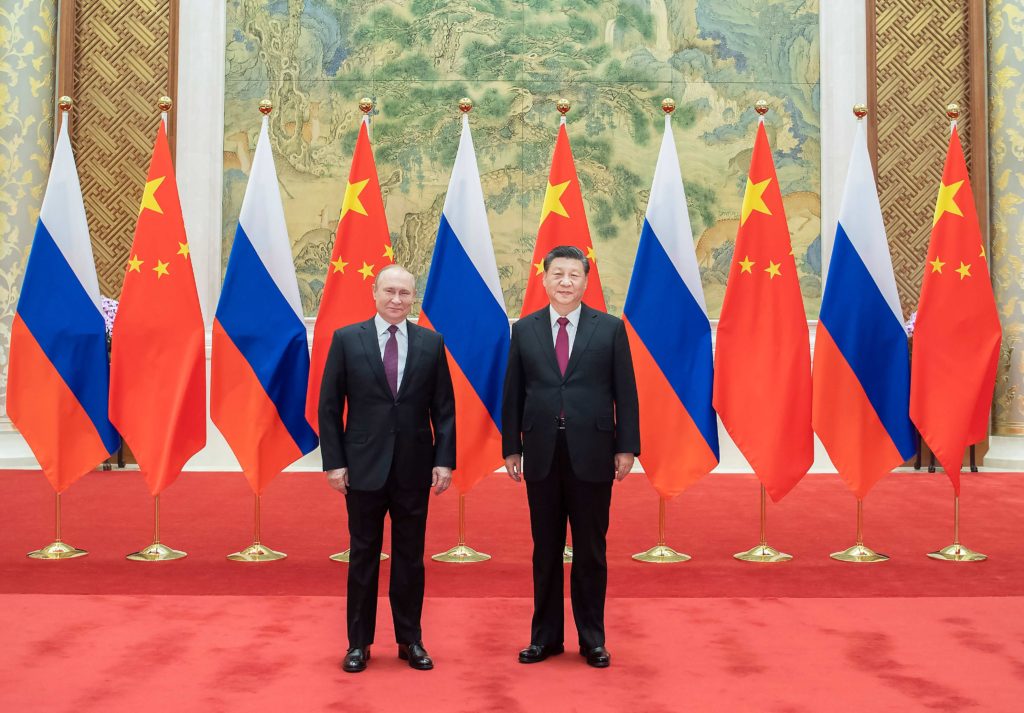

This was particularly needed because Putin’s nine-hour working visit to Beijing on Feb. 4, before the opening of the Beijing Olympics, gave the impression of China’s endorsement of the invasion. In the “Russia-China joint statement on the International Relations Entering a New Era and the Global Sustainable Development” signed by Putin and Xi, China expressed its opposition to NATO enlargement and “is sympathetic to and supports” Russia’s proposal “to create long-term legally binding security guarantees in Europe.” The joint statement also reaffirmed that “friendship between the two states has no limits” and “there are no ‘forbidden’ areas of cooperation” (for a full assessment of Putin’s Feb. visit, see PacNet #8 published on Feb. 16).

Figure 1 Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin pose for a photo prior to their talks in Beijing, China on Feb. 4, 2022. Photo: Alexei Druzhinin/Sputnik/Kremlin Pool Photo via AP

In retrospect, China’s concordance with Russia before the Beijing Winter Olympics was largely a response to Biden’s hardball approach to alliance-building and sanctions against both Russia and China. Regardless, closer alignment between Moscow and Beijing paralleled the further deterioration of US-China relations immediately after the start of the Ukraine conflict. On March 13, senior US officials leaked “intel” that Russia asked China for military assistance, a story rejected by both China and Russia. A few days later, Biden warned Xi of “consequences” if China provides “material support” to Russia. The US did not specify what constitutes “material support,” thus allowing unilateral interpretation by the US with grave implications for normal economic intercourse between China and Russia.

In addition, there has been heightened US diplomatic and military activities in China’s vicinity, including Taiwan (e.g., House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s planned, but ultimately aborted, visit to Taiwan on April 17). In addition, NATO’s preoccupation with the Ukraine conflict in Europe seemed to accelerate its extension into the Indo-Pacific. On April 27, UK Foreign Secretary Liz Truss made the forceful declaration that the UK rejected “the false choice between Euro-Atlantic security and Indo-Pacific security” in favor of “a global NATO,” and that NATO “must ensure that democracies like Taiwan are able to defend themselves.”

The Ukraine crisis, therefore, defies the conventional (but inaccurate) Western paraphrasing of the Chinese notion of “crisis” as two separate characters of “danger” (危) and “opportunity” (机). It is—by all means, and in its authentic connotation—a dangerous time and should be handled carefully.

A Conflict of Asymmetries and Attrition

In many ways, the current Ukraine War is the continuation and expansion of its first phase eight years before, including its timing, after a different Winter Olympics. The only difference was that after months of violent demonstrations, the Ukrainian opposition parties ousted pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovich before the end of the Sochi Winter Olympics. The ensuing Russian takeover of Crimea and eight years of low-level conflict in eastern Ukraine were typical “gray-zone operations” with restraint on both sides. This time, Moscow unleashed its battalion tactical groups (BTGs) three days after the Beijing Winter Olympics with World War II-style blitzkrieg operations, only to be forced back to World War I-like trench warfare in eastern and southern Ukraine.

Russia’s predicament was not unpredictable given the highly asymmetric nature of the conflict. Although Ukraine is much smaller and militarily weaker than Russia, it enjoys enormous support from the most powerful economic and military entities (EU and NATO), including access to round-the-clock intelligence, which was instrumental in the sinking of the Moscova, an icon of the powerful Soviet Navy. As the conflict continues and escalates, it is becoming increasingly clear that neither side can afford to lose. As a result, China’s balancing between the warring sides is becoming more delicate and difficult.

The Chinese government never used the singular term “neutrality” in its policy pronouncement on the Ukraine conflict. Instead, it described its policy as “aboveboard, objective, and impartial.” On March 15, China’s Ambassador to Washington Qin Gang reiterated these points in his article in The Washington Post as the principles of neutrality and impartiality. For conceptual clarity and brevity, the phrase “principled neutrality” is used here.

At the onset of the conflict, much of China’s effort was to sort things out with the Russian side. As the conflict dragged on, however, more attention was directed to the Ukrainian side. In his March 1 and April 5 phone calls with Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba, Foreign Minister Wang reiterated China’s “fundamental position” on the Ukraine issue as objective, transparent, and consistent, while emphasizing China’s deep concern about the damage done to civilians. On March 7, China put to the UN Security Council its six-point proposal for Ukraine’s humanitarian relief, including a point that humanitarian action must be neutral and avoid the politicization of humanitarian issues, and that effective measures should be taken to protect civilians and prevent secondary humanitarian disasters in Ukraine.

Between March 9 and 14, the Chinese Red Cross Society provided Ukraine with three batches of emergency humanitarian assistance (5 million yuan). Another 10 million yuan ($1.57 million) was added a week later. The two governments also worked together to evacuate 6,000 Chinese citizens in Ukraine, which was largely completed in early March. In a uniquely humanitarian effort to keep extended families together in a crisis, China is allowing Chinese citizens in Ukraine to bring with them the parents of their Ukrainian spouses.

Figure 2 Chinese Ambassador to Ukraine Fan Xianrong meets with Lviv Governor Maksym Kozytskyi on March 14, 2022. Photo: Ukrinform.net

To drive home China’s balanced policy on the Ukraine crisis, China’s Ambassador to Ukraine Fan Xianrong paid a visit on March 14 to Lviv Governor Maksym Kozytskyi and remarked: “I, as an ambassador, can say with responsibility that China is always an important partner of Ukraine in both economic and political terms…We will respect the path chosen by Ukrainians because this is the sovereign right of every nation.” Fan added that “China will never attack Ukraine…We are ready to help your development…We will take responsible actions. We have seen how the Ukrainian people demonstrated their strength and unity.”

Fan’s remarks were reported in Ukrainian media and endorsed later by the Chinese foreign ministry. Chinese media, however, only cited Ukraine sources for Fan’s remarks.

China’s carefully calibrated Ukraine policy is driven by at least three factors: 1) Ukraine, too, is China’s strategic partner. Despite the steady deterioration of relations between Moscow and Kyiv, China-Ukraine relations have largely been normal, and Ukraine had been more generous than Russia in military-technological transfers to China, 2) Ukraine has been a key component of China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). In 2019, China surpassed Russia to become Ukraine’s biggest trade partner. Two-way trade increased in 2021 by 35% to $18.98 billion and Chinese firms signed $6.7 billion in contracts in Ukraine in the same year, 3) China gains nothing from the Russia-Ukraine conflict. As in the case of China’s relations with Russia, the continuation and escalation of the Ukraine conflict will only increase China’s already difficult relations with the West in general and with the US in particular.

By the end of March, the 5th round of Russia-Ukraine talks in Turkey ended with signs of progress. Ukraine went as far as to propose adopting a neutral status while Russia started to scale down its military operations around Kyiv. When Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov arrived in China for the Third Foreign Ministers’ Meeting on the Afghan Issue Among the Neighboring Countries of Afghanistan on March 30, he had something positive to share with Chinese host Wang Yi: Russia was committed to de-escalating tensions and would continue peace talks with Ukraine and maintain communication with the international community.

Lavrov’s mission in China was to build relations with China “in a stable and consistent manner,” said Lavrov at the meeting with Wang Yi. He urged that “concrete steps” be taken to ensure that all agreements signed by the two heads of state a month ago be “consistently implemented,” according to Russian official media TASS.

In response to Lavrov’s subtle concern about China’s wavering support of Russia, Wang replied that China-Russia relations “withstood the new test of evolving international landscape, remained on the right course and shown resilient development momentum.” Regarding the Ukraine conflict, Wang reiterated that China supported Russia-Ukraine peace talks. China also looked for the de-escalation of tensions on the ground, and efforts by Russia and other parties to prevent a large-scale humanitarian crisis. In the long run, lessons should be learned from the Ukraine crisis, said Wang.

The preliminary outcome of the 5th round of Russia-Ukraine peace talks was nonetheless questioned by the West. The alleged Bucha killing of civilians by Russian forces in early April closed the door for a negotiated ceasefire, at least for the time being.

Limits of Sino-Russian “No-Limit” Strategic Partnership

The apparently unlimited potential of the Ukraine War to expand and escalate tested the limits of Russia-China bilateral relations.

The “unlimited” degree of the China-Russia strategic partnership was first articulated by Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi on Jan. 2, 2021. “In developing China-Russia strategic cooperation, we see no limit, no forbidden zone, and no ceiling to how far this cooperation can go (没有止境,没有禁区,没有上限),” he told Xinhua. He reiterated this to Lavrov in their Feb. 4, 2021 phone call.

In retrospect, Wang’s “no-limit” formula was driven by at least two factors. One was the search for a new conceptual framework to replace and transcend the traditional military alliance, which was dismissed repeatedly by both sides. Another driver of China’s search for new space to elevate relations with Russia was the Trump administration, when China-US relations hit a new low (over the trade war, the “Wuhan/China virus,” Taiwan, etc.). For Russia, closer ties with China were desirable at a time when the marked escalation of the low-level Ukraine conflict went hand-in-hand with the Biden administration’s anti-Russian actions in 2021 ($125 million in military aid to Ukraine on March 1, 2021, the first round of sanctions on March 2 for Russia’s handling of the Navalny case, and Biden calling Putin “a killer” on March 17).

When the “no-limit” phrase was written into the joint statement signed by the two heads of state on Feb. 4, 2022, both sides seemed to gain something. For Putin, who may have already made up his mind about the Ukraine invasion, the “no-limit” cooperation with China meant additional assurance of China’s neutrality, which was the case in the 2014 Crimea crisis. For Beijing, Putin’s presence at the opening ceremony of the Beijing Winter Olympics was indicative of Russia’s strong support when the West launched a diplomatic boycott. By no means was it considered a blank cheque by China for whatever Russia did.

Regardless, the Ukraine war radically shaped Western perceptions, or misperceptions, of China’s “no-limit” cooperation with Russia. To alleviate this “strategic conundrum,” China’s Ambassador to Washington Qin Gang clarified on March 25 that “although Sino-Russian cooperation has no limits, it does, however, have its bottom line, which is the principle of the UN Charter.” The end of the Ukraine conflict through negotiations at the earliest possible time, therefore, serves China’s interests as well as the interests of all sides. “A worse Russia-US relationship does not mean a better China-US relationship,” added Qin.

Qin’s clarification of China’s “no-limit” Russia policy was necessary, particularly for a newly appointed ambassador (who arrived at his post in July 2021). Other senior diplomats in China, however, continued to use the concept for at least one reason: the Feb. 4 China-Russia joint statement is already conditioned by the usual anti-alliance component: “The new inter-state relations between Russia and China are superior to political and military alliances of the Cold War era.”

Beyond the Ukraine conflict, the China-Russia strategic partnership has its own built-in “bottom lines” that set both upper and lower boundaries. As large and genuinely independent civilizational entities, Russia and China value their independence and sovereignty above all else. A military alliance with automatic interlocking mechanisms for security would inevitably deprive them of their freedom of action.

Perhaps more than anything else, current strategic ties between China and Russia are a pragmatic relationship without the interface of political ideology. In contrast, the same communist ideology exaggerated the friendship during the Sino-Soviet alliance of the 1950s and amplified disagreements during their 30 years as adversaries (1960-89). Both sides paid enormous political, economic, and strategic costs for the wild swing from friends to foes. Since the normalization of their relations in 1989, the two sides have turned that asymmetrical and highly ideological relationship into one of pragmatic coexistence with close and flexible coordination. And they have every reason to preserve that relationship regardless of external distractions.

Beijing’s Ukraine Discourse

Lavrov had every reason in his late March meeting with Wang to seek a more affirmative assurance for Russia’s war “to end US dominance.” For all the “unlimited” rhetoric, China’s support may not be automatic. First, there is the risk-averting behavior of Chinese companies that have already slowed down or avoided Russia-related activities, lest they be hit by secondary sanctions by the West. That is also why large Chinese banks are reportedly trying to circumvent direct operations with Russian clients. Although risk aversion is normal for any business, as was the case in the post-Crimea years, Russia is keenly aware of the constraints of the Chinese side and the limits of bilateral economic ties even in normal times.

It is the seemingly ever-divisive public and intellectual space in China regarding the Ukraine conflict that may have caused additional concerns for Russia. From his close monitoring of the Ukraine discourse in China, Alexander Lukin, one of the most prominent Sinologists of Moscow’s Higher School of Economics, noticed in his March 28 National Interest piece that China “has not yet formed its final position, which may be subject to change throughout the conflict.” China “won’t break with Russia over Ukraine but would persuade Russia to resolve the situation as quickly as possible.”

Lukin’s concerns about a polarizing Ukraine debate within China were echoed by Yan Xuetong of Tsinghua University in Beijing. In his Foreign Affairs piece on May 3, Yan described a “deepened political polarization within China by dividing people into pro- and anti-Russia camps.”

Both Lukin and Yan cited public opinion for their arguments. There is, however, a huge difference between the two. Whereas Lukin carefully documented some leading opinion leaders’ views, Yan cited only “anti-Russian sentiments” as evidence of China’s highly polarized public space.

Both, however, ignored the “not-so-silent” majority in China’s rapidly expanding Internet. Any casual peek at the vast Chinese chatrooms would reveal an active and diverse pool of opinions regarding the war. Official media may have contributed to this by being impartial with coverage of both Russian and Ukrainian official views. As a frequent commentator for CCTV’s popular experts’ panel Focus Today (今日关注), Professor Wu Dahui (吴大辉), a prominent expert on Russian and Ukrainian affairs, went as far as to cite directly from his own “deep throat” inside Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s inner circle. In late April, China’s official Xinhua news service published the full texts of its interview with the Russian and Ukrainian foreign ministers. It was not a surprise that a recent survey indicates that 30% of respondents support Russia’s “special military operations,” 20% side with Ukraine, and 40% remain neutral.

Figure 3 Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov. Photo: CGTN

Figure 4 Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba Photo: Lev Radin/Getty Images

Beyond Ukraine, an increasing number of Chinese people with globalized interests and experiences, as well as foreign language capabilities, naturally prefer stability and predictability for their professional and personal activities. Their inclination toward a more balanced approach to the Ukraine conflict, or any conflict, has to be taken seriously by the government. In this regard, Beijing’s principled neutrality is not just a “strategic predicament,” but also a reflection of the interests of the Chinese, no matter how difficult it is to operationalize.

A more important issue is how to interpret diverse views of the Ukraine conflict among China’s intellectual elite. Both Lukin and Yan gave disproportional attention to a few leading critics of China’s “pro-Russia” stance. Lukin nonetheless put them in the category of “private opinions not directly related to the official line.” Yan, however, equated these rather minority views, albeit more vocal now, with a broad “anti-Russian sentiment among some Chinese citizens.”

Those few “anti-Russian” academics, however, have been anti-Russia long before the current Ukraine conflict and have devoted much of their professional life to reminding their audiences about China’s lost territories to both Czarist and Communist Russia. For better or for worse, they have been part of a diverse academic community, albeit with a trivial impact on policymaking. The Russian invasion of Ukraine, however, provided an opportunity to amplify their obsession with the past. And this time, they are joined by a sizeable Western-oriented intellectual elite, who were embarrassed, dismayed, and largely silenced by Trump’s assaults on US political institutions, as well as his extremely hostile and racialized China policy (e.g., Kiron Skinner’s “civilization conflict” against a “non-Caucasian” China).

Yet even for the intellectual elite, Yan’s Foreign Affairs piece missed a much larger group of political realists working on both Russian studies and broadly international relations. They are not necessarily pro-Russia or anti-US but are pragmatic and professional. The Ukraine discourse in China, therefore, should be understood as an interactive dynamic between at least three groups: policymakers, the general public, and the intellectual elite.

Finally, China’s neutrality regarding the Ukraine conflict was the natural extension of China’s “independent foreign policy,” officially adopted in 1982 after China’s huge swings between its “one-adversary” (anti-US in the 1950s and anti-Soviet Union in 1972-1981) and “dual-adversary” strategies (1960-71). These one-sided foreign policies were products of both the Cold War and a highly politicized and ideological domestic setting.

Conclusion: A Tale of Two Neutralities

The last time China declared neutrality in Russia’s war was 118 years ago, when Japan’s ascending Empire of the Sun was battling the vast and decaying Czarist Russia, ironically, in northeastern China. The Qing’s neutrality in a war on its own territory did not save the dying dynasty. It was the “neutral” US from the other side of the Pacific that brokered a deal for the warring sides. For this grand deal (at the expense of the sovereignty of both Korea and the Philippines), US President Theodore Roosevelt won the Nobel Peace Prize. The end of the brutal Russo-Japanese War in China, however, was only the beginning of more wars, disunity, and social revolutions in Asia in the first three-quarters of the 20th century.

In contrast to these formative decades of endless civil and foreign wars when China was weak and divided, its steady rise since the 1979 historic economic reforms has been accompanied by a largely stable and increasingly prosperous East and Southeast Asia. A de facto US-China rapprochement has also been instrumental for this state of affairs in the not-so-orderly post-Cold War Pax Americana (e.g., in the greater Mideast and now Europe). Many in China, therefore, prefer to stay away from the current Ukraine war, which can be defined as Huntingtonian “Western civil war” 2.0 (in his 1993 treatise “Clash of Civilizations,” Harvard political scientist Samuel Huntington argued that the end of the Cold War meant the end of “Western civil wars” since the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia), for both China’s own interests and global stability.

China’s current balancing moves can also be understood as an effort to return to its Confucian past for wisdom in a world of chaos. A key component of Confucianism is being moderate (中庸) or staying in the middle while avoiding extremes. In his 2011 On China, Henry Kissinger defined traditional China’s policy toward its neighbors as one of impartiality and pragmatism, which is very similar to Ambassador Qin Gang’s depiction of China’s principled neutrality in the current Ukraine crisis.

It remains to be seen how China’s principled neutrality would affect the increasingly dangerous Western civil war 2.0.

Jan. 7, 2022: President Xi Jinping sends a message to Kazakh President Askar Katayev that China strongly opposes any effort to sabotage and threaten Kazakhstan’s stability, security, and Sino-Kazakh friendship and cooperation.

Jan. 10, 2022: State Councilor and Foreign Minister of China Wang Yi and Russian FM Sergei Lavrov talk over the phone, with Wang telling Lavrov that China and Russia should not allow chaos in central Asia.

Jan. 17, 2022: Lavrov tells a news conference that Russia-China friendship is not against anyone.

Jan. 18-20, 2022: Russia, China, and Iran hold their second joint naval exercises in the Gulf of Oman. They practice sea-lane protection, anti-pirates, and hostage-rescue operations.

Jan. 25, 2022: Xi holds a virtual summit commemorating the 30th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and five Central Asian countries (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan).

Feb. 3, 2022: Lavrov travels to Beijing ahead of Putin’s official visit. He meets his Chinese counterpart Wang Yi. On the same day, the Russian President publishes his article in China’s Xinhua news agency: “Russia and China: A Future-Oriented Strategic Partnership.”

Feb. 4, 2022: Putin visits China. Before joining the opening ceremony of the Beijing Winter Olympics, he holds a lunch talk with President Xi, and 15 documents are signed. The two heads of state also issue a joint statement on international affairs.

Feb. 22, 2022: Russian Parliament grants Putin’s request to use the military to back Ukrainian separatists.

Feb. 24, 2022: Lavrov talks over the phone with Wang Yi. They discuss the situation in eastern Ukraine.

Feb. 25, 2022: Xi speaks with Putin on the phone. Putin briefs Xi on Russia’s “special military operation” in Ukraine.

Feb. 26, 2022: Wang puts forward a “five-point” stance on the Ukraine conflict.

Feb. 27, 2022: Putin puts the Russian nuclear force on high alert.

March 1, 2022: Wang talks to Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba at the latter’s request.

March 2, 2022: Lavrov says that “World War III would be a devastating nuclear war.”

March 14, 2022: Chinese Ambassador to Ukraine Fan Xianrong pays a visit to Lviv Governor Maksym Kozytskyi. He expresses support for Ukraine.

March 17, 2022: Chinese Foreign Ministry’s spokesman Zhao Lijian says that the Foreign Ministry supports Fan’s statement on March 14, 2022.

March 18, 2022: Xi and Biden talk over the phone about the Ukraine War.

March 21, 2022: Wang pays an official visit to Pakistan.

March 22, 2022: Wang is invited to address the opening ceremony of the 48th session of the Council of Foreign Ministers of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) in Islamabad, the first time a Chinese Foreign Minister is invited to such a meeting.

March 24, 2022: Wang visits Afghanistan.

March 25, 2022: Wang visits India.

March 29, 2022: 5th round of peace talks for Ukraine end with a written document for a ceasefire. Ukraine reportedly proposes adopting neutral status and a 15-year consultation period on the future of Russian-occupied Crimea as long as a complete ceasefire with Russian forces is agreed.

March 30-31, 2022: Wang chairs the 3rd Foreign Ministers’ meeting among neighboring countries of Afghanistan in Tunxi of China’s Anhui Province. He held talks with Lavrov on the sidelines of the conference. FMs or representatives of Pakistan, Iran, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan attended the meeting.

April 1, 2022: Xi meets via video with President Charles Michel of the European Council and President Ursula von der Leyen of the European Commission. They exchange views on the Ukraine conflict.

April 4, 2022: Wang talks to Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba at the latter’s request.

April 4, 2022: Bucha’s massacre is first reported.

April 14, 2022: Wang talks to his Vietnamese counterpart. Wang reportedly said that the Ukraine tragedy should not be allowed to be repeated around China.

April 15, 2022: Li Zhanshu, Chairman of the National People’s Congress Standing Committee, holds virtual talks with Russian Federation Council Speaker Valentina Matviyenko.

April 18, 2022: Vice Foreign Minister Le Yucheng meets in Beijing with Russian Ambassador to China Andrey Denisov.

April 25, 2022: Chinese Defense Minister Wei Fenghe visits Kazakhstan.

April 26, 2022: Chinese Defense Minister Wei Fenghe visits Turkmenistan.