Articles

It took time for Tokyo and Washington to understand the scope of the COVID-19 crisis, as the virus continues to spread in both Japan and the United States. The routine that would normally define US-Japan relations has been set aside, but it is too early to draw inferences about what this pandemic might mean for the relationship, for Asia, or indeed for the world. At the very least, the disease confounded plans in the United States and Japan for 2020. COVID-19 upended the carefully developed agenda for post-Abe leadership transitions in Japan and threw President Trump, already campaigning for re-election in the November presidential race, into a chaotic scramble to cope with the worst crisis in a century.

The pandemic has confounded virtually all political, economic, and diplomatic activity. Borders closed, states imposed lockdowns or stay-at-home orders on their citizens, and economic activity screeched to a halt. It took time for Tokyo and Washington to understand the scope of this crisis, and the virus continues to spread in both Japan and the United States. The routine that would normally define US-Japan relations has been set aside, but it is too early to draw inferences about what this pandemic might mean for the relationship, for Asia, or indeed, for the world. Some believe that everything has changed, while others argue that the outbreak of COVID-19 has simply accelerated an already shifting geopolitics.

At the very least, this spreading disease confounded plans in the United States and Japan for 2020. COVID-19 upended the carefully developed agenda for the post-Abe leadership transitions in Japan and threw President Trump, already campaigning for re-election in the November presidential race, into a chaotic scramble to cope with the worst crisis in a century. Japan confirmed its first case of COVID-19 on January 16, followed five days later by the US announcement of its first case. The governments of Japan and the United States, like every other government around the globe, struggled with the lethality of this virus as it became increasingly obvious it could not be contained.

The impact of the pandemic on Japan and the United States has differed considerably, with Japanese infections and deaths far lower than those in the United States. The US-Japan relationship was tested early on with the arrival in Japan of a cruise ship with thousands of international passengers, 416 of them Americans. But it was the larger challenges posed by the global spread of the virus that were noteworthy. Tokyo and Washington’s relationship with China, the site of the original breakout, revealed some differences in the longer-term preferences of each ally. While too early to know the full extent of the virus’s damage, the US and Japan will face protracted economic recoveries and will likely have to cope with a massive global economic downturn that will add to their misery.

Even as the pandemic absorbs the attention of the president and the prime minister, there is a continuing need for ever-closer security cooperation. It is too early to tell if this broader crisis will undermine alliance strategic cooperation, but there are hurdles on the horizon. Host Nation Support talks are on the calendar this year, and the Trump administration has dug its heels in with its demand for a five-fold increase in spending for US forces from its other Northeast Asian ally, South Korea. US-Japan talks could be similarly acrimonious. The tempo of Chinese PLA activities in the South and East China Seas continued unabated, raising the pressure on Japan’s SDF, and rumors of Kim Jong Un’s demise, while seemingly inaccurate, suggest that the United States and its regional allies are unprepared for serious instability on the Korean Peninsula. As both the Abe Cabinet and Trump administration are focused on managing the public health crisis, Asia’s complex geopolitics continue to challenge the US-Japan alliance.

Early COVID-19 Responses

As the year opened, the emergence of a new, lethal virus caught Tokyo and Washington by surprise. Each encountered the virus differently. As news of this virus found in Wuhan, China, was shared across the globe, both the Abe Cabinet and the Trump administration looked to their citizens who had traveled to China. For Japan and the United States, two considerations emerged. The first was how this would affect not only those who had recently been in China, but also economic ties between the two countries. In January, all four cases of Japanese with COVID-19 had some direct exposure in China. The United States similarly began to examine those who had traveled to China. Both Tokyo and Washington banned travel to China, and quarantined those who arrived in their respective countries from China. On January 31, the United States limited all travelers from China, whereas Japan focused only on those from Hebei Province and its capital, Wuhan. A few days before the announcement, both countries sent chartered flights to get their citizens out of Wuhan and back home to quarantine in their respective countries.

The US and Japanese governments had to cooperate in February in dealing with the contagion of passengers on a cruise ship in Japan after a passenger who left at Hong Kong tested positive for the virus. The Diamond Princess docked at Yokohama harbor on February 3 and its passengers were subjected to a 14-day quarantine. Japanese authorities began testing the 2,666 passengers and 1,045 crew members. Those who tested positive were taken off for quarantine in Japanese medical facilities. As the days dragged on and the number of infected grew, the Trump administration requested that US citizens on the ship who wanted to return to the United States for quarantine be transported out of Japan. Two charter flights were organized. Controversy over how passengers were taken off the ship and transported to Haneda International Airport soon surfaced when it became known just prior to boarding that some on the flight had tested positive for the virus. A makeshift curtain was put up on the aircraft, but the impression of helter-skelter disembarkation from the Diamond Princess went beyond the US evacuation. A Japanese epidemiologist went public on February 18 in a YouTube video about what he saw as unacceptable quarantine practices on board, triggering a public backlash against the Abe government.

Infectious disease experts at the Ministry of Labor, Health, and Welfare, who argued for tracing the contacts of those who tested positive, guided Japan’s initial response. This cluster approach was embraced by the panel of experts later convened by the prime minister on February 17, led by Wakita Takaji, chief of the National Institute of Infectious Diseases. One early cluster, identified in Hokkaido, prompted the local governor to order a shutdown on February 28, but for the most part the country went about its business as usual. But testing was limited to only those with direct contact with China or others who had tested positive for COVID-19, which beyond the Diamond Princess cases was a small number even as late as the end of February.

The Diamond Princess off Yokohama Port on February 4, 2020. Photo: Asahi Shimbun

However, when it became clear that Japanese who had neither travelled to China nor had contact with anyone on the cruise ship were coming down with the virus, the Abe Cabinet had to switch gears. March was also the season for cherry blossom viewing, and even though Emperor Naruhito in February had set the tone by canceling his birthday celebration, many Japanese did not stay home, nor did they abandon large gatherings and busy subways. Gov. Koike Yuriko of Tokyo also began to urge the capital’s residents to remain at home. Governors in Japan, unlike those in the United States, had no authority to compel their citizens to stay at home.

By the end of March, Tokyo’s numbers were accelerating and made up 30% of Japan’s total cases. New legislation was drafted to manage the COVID-19 outbreak, and the new law was enacted on March 13, clearing the way for Abe to declare a state of emergency for Japan’s urban centers and their suburbs on April 6. Seven prefectures were included: Tokyo, Chiba, Saitama, Kanagawa, Osaka, Hyogo, and Fukuoka. A week later, as the number of cases in Tokyo accelerated and others around Japan began to see an uptick in the number of infections, Abe extended the emergency to the entire country. Nonetheless, even Japan’s prime minister did not have the authority to enforce a lockdown, and instead promoted what the Cabinet called the “Three Cs” that the public should try to avoid: closed, crowded, and close-range conversations. As of May 1, Japan announced a total of 14,281 cases and 432 deaths, suggesting that while the infection is still spreading, the rate of growth in Japan’s numbers may have stabilized.

A delay in recognizing the dangers of community transmission of the disease was also evident in the United States, but with far greater losses of life. Additionally, the US government response was chaotic, and the number of infections, as well as deaths, far outpaced Japan’s. Trump’s initial dismissal of the novel coronavirus as less lethal than the flu ran counter to medical expert concerns about the spreading infection. At the end of January, the Trump administration declared the coronavirus outbreak a public health emergency and restricted travel from China, but with just six cases confirmed the administration did not seem ready to acknowledge a threat to the United States. But by February 26, as the number of known cases grew to 60 and the CDC reported a person without any known exposure became infected in Northern California, the president ordered the formation of a new task force, led by Vice President Mike Pence, comprised of senior medical advisors such as Dr. Deborah Birx, US Global AIDS Coordinator at the Department of State, and Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes for Health (NIH). Two weeks later, on March 13, Trump finally declared a national emergency over the outbreak as confirmed cases climbed to more than 2,100. A second, unofficial group was then ostensibly assigned to oversee federal government cooperation with private companies to address the shortage of test kits, PPE for medical personnel, and ventilators under the direction of the president’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner. Despite promises of immediate results, the president resisted calls to use the Defense Production Act to ramp up production in the United States of much-needed medical supplies.

Unprecedented in the United States was the absence of federal government coordination of the pandemic response, and the deliberate devolution of responsibility to state governors. Washington Gov. Jay Inslee and New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo led the initial US public response as Seattle and New York City cases jumped in March. The National Governor’s Association, chaired by Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan, also began to coordinate and compare notes on COVID-19 best practices, drawing not only on the experiences of other states but also reaching out to countries such as South Korea, China, and Taiwan that had successfully stabilized outbreaks of the deadly virus. Complaining that the lack of a coordinated federal government response led to competitive strategies between states, Cuomo called for a greater federal role in coordinating the overseas purchase of medical supplies. Yet even as states ordered supplies from abroad, the federal government took a different tack, intervening and reportedly confiscating supplies on order by state governments. In an interview with the Washington Post, Hogan bluntly acknowledged the need to assign national guard troops to protect his supply of 500,000 masks purchased from South Korea.

As of May 1, whereas the number of Japan’s new COVID-19 cases seems to be slowing, the CDC had confirmed over 1 million cases in the United States and more than 64,000 deaths. Major metropolitan areas surrounding economic hubs such as New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Seattle, Detroit, Miami, and New Orleans have the highest concentration of cases. All are struggling to handle the public health crisis, and the burden of the disease on the African-American community has been particularly heavy. Governors and state legislators deliberating the decision to extend the shutdown in Michigan, Minnesota, North Carolina, Ohio, and Washington have been met with protestors, many of them armed, demanding to be released from government control. The Trump administration has begun to emphasize its interest in reopening the US economy even as scientists warn that a premature end to the stay-at-home orders could result in a serious acceleration of infections. Public opinion also seems to be cautious about lifting social isolation practices, revealing some distance even between the White House and the president’s supporters. The political divisions characterizing US politics have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, and will likely prevent a consensus on an effective national public health response prior to the November election.

Blaming China?

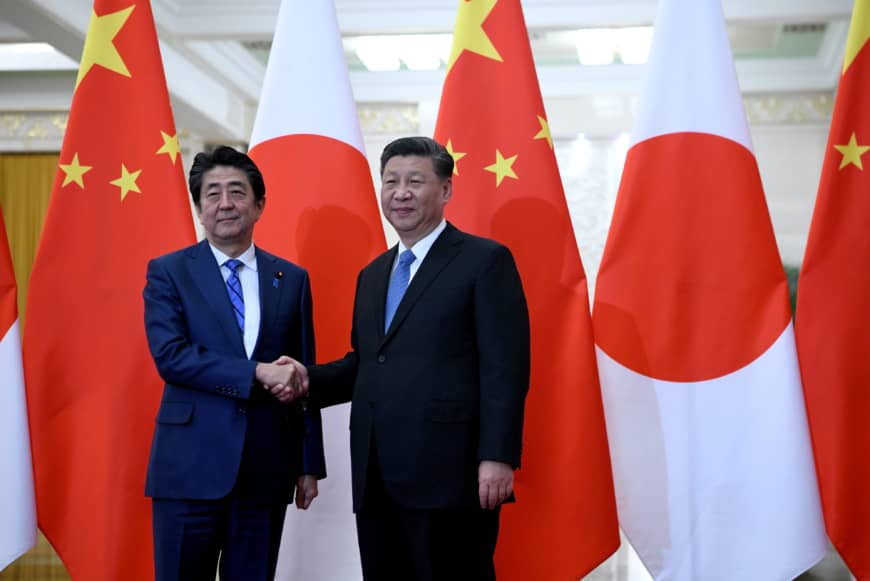

The COVID-19 crisis also complicated each country’s relations with China; it accelerated an already poisonous relationship between Washington and Beijing while it derailed a carefully scripted effort at bilateral summitry between Japan and China. Trump initially praised President Xi Jinping for his handling of the outbreak, but the president shifted gears in March as the US epidemic took off. In contrast, Prime Minster Abe has not been willing to enter into the blame game, instead looking to shore up global cooperation in managing the pandemic.

Japan’s diplomacy with China suffered a significant setback, however. Xi was due to arrive in Tokyo in April for a much-anticipated state visit, culminating a long and carefully choreographed effort at improving Japan-China ties. Neither Beijing nor Tokyo wanted to call off the visit in the early weeks, but by March 5 both governments announced that the epidemic required postponement.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and President Xi Jinping in Beijng in December 2019. Photo: Reuters

In contrast, the COVID-19 pandemic has hastened a showdown between the United States and China. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo urged his counterparts at the G7 meeting to identify it as the “Wuhan virus,” but European and Japanese foreign ministers declined and the meeting ended without a joint statement. Some have attributed this effort to pin blame on China to the anti-China hawks known to be on the president’s staff. A Washington Post article, however, assigns responsibility for laying blame on China for COVID-19 to Deputy National Security Advisor Matt Pottinger, the Asia policy lead. Wrangling over what to do about China’s effort to turn this into an opportunity to assert regional and global influence also comes from within Japan’s foreign policy makers.

The US election campaign will focus heavily on China. Trump is expected to campaign on his success in bringing China to heel on trade, and the global pandemic will also provide ample fodder for depicting China as being hostile to US interests. An article in the American Interest, attributed to a senior foreign policy official in the Japanese government, laid out Japanese fears about going back to the policy of engagement used by the Obama administration to deal with China. As Obama’s Vice President, Joe Biden and his campaign team seemed to be the author’s main audience. While Tokyo pursues its own engagement with the government of Xi Jinping, strategic competition between the United States and China offers Japan an opportunity to deepen ties with others in the Indo-Pacific. The complex interplay between Tokyo and Washington on how best to confront authoritarian China continues to shape alliance dynamics.

Staggering Economic Impact

Within Japan, the staggering economic impacts of COVID-19 fed into an already laggard economy. The consumption tax had dimmed growth in the fourth quarter of 2019, as GDP shrank at an annualized rate of 6.3% from the previous quarter (a number later revised to an even greater drop). COVID-19 was set to have a far greater impact. By February, tourism to Japan had dropped by 58.3% compared to a year earlier, and in March, by 93%. This marked the biggest decline ever recorded, topping the previous record set by a 62.5% drop in April 2011, the month after the earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear triple disasters hit Japan. Figures for tourism in the United States were similarly stark. The US Travel Association estimated that the decline in travel could lead to a loss of $910 billion in economic output, “more than seven times the impact 9/11 had on travel sector revenue.”

While tourism is among the hardest hit industries, the effects of COVID-19 have been widely felt across both economies. Stock markets in both the United States and Japan saw huge falls in the first quarter of the year, plunging the most since the 1987 “Black Monday” crash, although since then stocks have rebounded. Oil prices tanked as a result of drastically reduced demand, and even fell below zero for the first time in history. In the United States, the number of people seeking work hit a record high, as 30 million Americans filed for unemployment between mid-March and the end of April, representing over 18% of the labor force. Japan, known for its relatively low unemployment rate, has seen less impact thus far on jobs, although there are worries about what will happen in the coming months to nonregular employees, who account for nearly 40% of workers but may not be eligible for unemployment insurance. All in all, the International Monetary Fund has estimated that the global economy will shrink by 3% this year, marking the sharpest downturn since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Governments in the United States and Japan have responded to COVID-19 with record-setting stimulus packages. The US government enacted a set of bills, beginning with the $8.3 billion Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act on March 6 and the $192 billion Families First Coronavirus Response Act on March 18. It was the third phase of Congress’ coronavirus response, however, that got the most attention, when the government enacted the $2.3 trillion (11% of GDP) Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act on March 27, the largest stimulus bill in US history. The stimulus package included loans for businesses, assistance for hospitals, transfers to state and local governments, expanded unemployment benefits, and provided one-time cash payments of up to $1,200 for Americans below a set income level. The $359 billion set aside for loans for small businesses proved especially popular, and quickly ran out. On April 24, the government implemented the $484 billion Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act, which provided an additional $310 billion in loans for small businesses.

Japan’s own fiscal stimulus package was similarly unprecedented. On April 7 (revised April 20), the government adopted the 117.1 trillion yen ($1.1 trillion) Emergency Economic Package Against COVID-19, representing a staggering 21.1% of Japan’s GDP. The package included subsidies for small- and medium-size businesses, transfers to local governments to provide financial aid for companies, medical assistance, and universal cash handouts of 100,00 yen ($936) per individual, a revision from the original plan to give out 300,000 yen ($2,808) to the most affected households that reportedly came as a result of pressure from the LDP’s coalition partner, Komeito. The stimulus was more than double the size of the 58.6 trillion ($548.7 billion) yen package passed in April 2009 to respond to the global financial crisis, and over four times the size of the 26 trillion yen ($243 billion) stimulus bill enacted in December 2019 to help the economy recover from the consumption tax hike. In addition to its size, the Japanese government’s funding for companies to relocate out of China was also noteworthy. The coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan affected Japanese manufacturers’ supply chains, diminished imports to Japan, and made companies operating there uneasy about the future. A survey by Tokyo Shoko Research in February revealed that 37% of the 2,600 companies doing business there were looking for ways to leave and relocate their businesses. Abe’s stimulus included 243.5 billion yen ($2.2 billion) to help them do so.

The most painful blow for the Abe administration, however, may be the postponement of the 2020 Olympic Games. While the government initially held out hope that the games could go ahead as planned, after Canada and Australia announced that they would skip the games in mid-March due to concerns for the health of their athletes, Japan and the International Olympic Committee (IOC) announced on March 24 that they would postpone the games to July 23-August 8, 2021. Early estimates of how much the yearlong delay will cost Japan range from $2 billion to $6 billion. Officially, the Japanese government has said that it is spending $12 billion on the games, but government auditors said back in December that it would likely cost twice as much. As new expenses and logistical challenges accumulate, at issue too is to what extent the Japanese government will have to shoulder the costs of delay compared to the IOC. Moreover, while Japanese officials have referred to the rescheduled Tokyo Olympics as a potential “beacon of hope” for the world, there is also a lingering worry that the games might have to be cancelled altogether, a prospect some analysts suggest would cost Japan more than $42 billion.

Tokyo 2020 Olympics President Yoshiro Mori holds the Olympic Flame at a ceremony in Higashi-Matsushima, Miyagi prefecture in March. Photo: Reuters

Lastly, the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to have lasting impacts on international trade, not only between the United States and Japan but also between the two allies and China. Japan’s exports fell by 11.7% in the year to March, including an 8.7% decline in exports to China. Shipments to the United States sank further, falling 16.5% year-on-year in March, the sharpest decline since April 2011. Import shocks were even larger: Japan’s total imports shrunk by 14%, including a steep 47.1% drop in imports from China over the previous year. On the US side, trade with China took a similar hit, as imports fell by 20.8% in March compared to last year and exports declined 12.6%.

At the end of 2019, it had looked as though 2020 might be the make-or-break year for the Trump administration to finalize new bilateral trade agreements with both China and Japan. As COVID-19 continues to dominate the attention of policymakers in all three countries, however, it remains to be seen how much appetite there is to resume tough negotiations on trade deals.

Keeping an Eye on US-Japan Military Cooperation

Both national militaries have been put to work to cope with the coronavirus outbreak. In Japan, the Self-Defense Force hospitals were used to help with the caseload, and SDF medics were sent to help Diamond Princess passengers disembark. In the United States, Trump sent two military hospital ships, one to New York and another to Los Angeles, to help alleviate pressures on local hospitals. On May 1, Trump announced that the United States would deploy 1,000 medical military personnel to New York City to provide further assistance. In many states, the National Guard, under the authority of the governors, were mobilized to help.

While the number of SDF personnel affected by the virus is unclear, US forces stationed in and around Japan have been affected. US Forces Japan reported its first infection on March 26, but by late April cases appeared to be dropping, with fewer than 30 cases at Yokosuka Naval Base and 6 cases at Camp Zama. US Forces in neighboring South Korea also reported relatively few cases, with 14 personnel infected as of April 1. In a highly-publicized incident, the commander of the USS Theodore Roosevelt ordered to quarantine his ship offshore Guam, appealed for more help when more than 100 of the over 4,000 sailors on the ship were infected. Then Acting Secretary of the Navy Thomas Modly fired the captain, who later turned out to test positive himself for COVID-19, and traveled to Guam on April 6 to tell the crew that if Crozier thought his letter wouldn’t become public, then he was either “too naïve or too stupid to be a commander of a ship like this.” Modly resigned the next day amid criticism of his remarks, and the US Navy has recommended reinstatement of Capt. Crozier.

Capt. Brett E. Crozier of the USS Theodore Roosevelt addresses the crew of the aircraft carrier in 2019. Photo: US Navy/Reuters

Chinese officials have been quick to point out that their ability to contain the virus has resulted in the continued readiness of their forces, and activities in and around the South and East China Seas continued unabated. Already incidents between the PLAN and US and Japanese navies have been increasing, which led to the deployment of the USS America, an amphibious assault ship, to Malaysian waters to demonstrate presence. The East China Sea also had its share of incidents. Several naval vessels, one Japanese and another Taiwanese, reported collisions with Chinese fishing vessels in the East China Sea in March. The JS Shimakaze, a missile destroyer, was on a routine patrol from its home port of Sasebo when the incident happened. An investigation is ongoing.

Finally, the US-Japan alliance awaits the initiation of talks on the renewal of the five-year Host Nation Support Agreement that provides Japanese contribution to the maintenance of US forces in Japan. To date, US-ROK talks on military cost-sharing have rattled Tokyo. The Trump administration’s demand for a five-fold increase in Seoul’s contribution, accompanied by threats of downgrading or even withdrawing US forces on the peninsula, have shown a hardline transactional approach to the longstanding burden-sharing deliberations between the US and its Asian allies. Even with the outbreak of a global pandemic and Korea’s offer of a 13% increase in its spending on US forces there, Washington continues to demand more money from Seoul, and implemented Secretary of Defense Mark Esper’s threat to furlough South Korean workers from US bases in South Korea unless the ROK increase its payments further. With bilateral talks expected to begin this summer or fall, Japanese officials wait to see if and how these US demands will affect their security cooperation.

Conclusion

Like elsewhere, the governments of Japan and the United States have been overtaken by the demands of responding to COVID-19 in the early months of 2020. Slow at first to grasp the public health crisis, the Abe Cabinet shifted gears in March to impose a national state of emergency, which has now been extended to May 31. The Trump administration, in contrast, directed governors to take the lead in determining local response, and has issued guidelines for reopening economic activity in areas where the pubic health crisis has abated. A more detailed set of guidelines issued by the CDC, however, was reportedly rejected by the White House over concerns that they were too severe and risked further hurting the economy.

The US-Japan relationship has fared better than other alliances in the Trump era, but the fate of the two leaders is now less certain. Abe’s agenda has been derailed, as the postponement of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics upset what was meant to be a celebratory end to his tenure as Japan’s longest serving prime minister came to a close. The US presidential election looms large for the Trump administration as its handling of the public health crisis has shaken the president’s approval rating. Criticism has been harsh, prompting some to conclude that the administration’s handling of the public health crisis has revealed the US to be a “failed state.”

Abe, too, has watched his approval numbers drop as even his supporters watched his handling of the virus. Both have been criticized for their delayed response. The editorial board of the Yomiuri Shimbun was quite blunt: “Even though there is a lot that we don’t yet know about this new coronavirus, the Abe Cabinet’s response to date has been far from strategic.” Japanese social media targeted Abe’s announcement that the government would send two masks to every family, a policy that was cynically dubbed as “Abenomask,” and his video of being at home in self-isolation.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe announces his plan to distribute cloth face masks to Japanese households at an April government task force meeting. Photo: Asahi Shimbun

Difficult decisions for Tokyo and Washington remain as few expect the pandemic to end soon, or easily. Neither government can yet claim to be on the other side of the curve of their country’s COVID outbreak. Nor is there widespread confidence in how they will handle what comes next. Managing the transition between now and the production of a vaccine that can render Japanese and Americans safe from infection will take months if not years. The economic consequences will be devastating for both nations. A second wave of infections in the fall seems all but assured. Politics in both nations could become far more complex if Japanese and Americans remain dissatisfied.

The impact of COVID-19 on the geopolitics of Asia cannot be underestimated, but neither can it be fully anticipated. For Tokyo, managing its relationship with China has only grown more difficult, and the pandemic suggests even greater strain. The economic ties that largely allowed Tokyo and Beijing to weather the worst of their periodic storms may unravel. US-China ties are already worse, as the battle over blame for COVID-19 has unleashed threats of unprecedented economic sanctions from Washington. If the Trump administration imposes financial costs on China, some form of economic retaliation is all but guaranteed, with spillover effects for the global economy. This would be especially hard on Japan given the already severe economic consequences of the pandemic. The US presidential election could also rattle US-Japan ties. The economic impact, however, has only just begun, with warnings of consequences far worse than the Depression of the 1930s. 2020 is already far less predictable, and more threatening, than leaders in either Tokyo or Washington could have imagined. It could get far worse.

Jan. 2, 2020: United States International Development Finance Corporation (DFC), which consolidates OPIC and USAID’s Development Credit Authority, officially begins operations.

Jan. 8, 2020: Deputy Secretary of State Stephen Biegun meets with National Security Secretariat Secretary General Kitamura Shigeru in Washington, DC.

Jan. 10, 2020: United States, Japan, and Mongolia hold trilateral meeting in Washington, DC. Joint Statement.

Jan. 14, 2020: Secretary of State Mike Pompeo meets Foreign Minister Motegi Toshimitsu in Palo Alto, CA

Jan. 14, 2020: Secretary of State Pompeo, Foreign Minister Motegi, and South Korean Foreign Minister Kang Kyung-wha hold a trilateral meeting in Palo Alto, CA.

Jan. 14, 2020: Secretary of Defense Mark Esper meets Defense Minister Kono Taro at the Pentagon.

Jan. 16, 2020: Japan confirms its first case of COVID-19.

Jan. 19, 2020: Motegi, Kono, Pompeo, and Esper issue a joint statement to mark the 60th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between Japan and the United States.

Jan. 21, 2020: United States confirms its first case of COVID-19.

Jan. 24, 2020: Joint meeting of Japan-United States Strategic Energy Partnership is held in Washington, DC. Joint Statement.

Jan. 30, 2020: WHO declares a global health emergency over the COVID-19 outbreak.

Jan. 31, 2020: President Trump enacts travel restrictions on foreign nationals who had visited China in the past 14 days.

Jan. 31, 2020: Prime Minister Abe Shinzo announces ban on entering Japan for foreign nationals from China’s Hubei province.

Feb. 1, 2020: Diamond Princess cruise ship stops in Naha, Okinawa, and completes a short quarantine before departing for Yokohama.

Feb. 1, 2020: Hong Kong government announces that a passenger on the Diamond Princess who disembarked on Jan. 25 has tested positive for COVID-19.

Feb. 3, 2020: The Diamond Princess docks off Daikaku Pier in Yokohama Port and is immediately quarantined.

Feb. 4, 2020: US Forces Japan implements a 14-day quarantine for people returning from China.

Feb. 5, 2020: Trump is acquitted of two impeachment charges by the Senate.

Feb. 5, 2020: Authorities extend the quarantine for the Diamond Princess by 14 days after 10 people onboard test positive for COVID-19.

Feb. 15, 2020: US Embassy in Japan announces that the US government will charter an aircraft to evacuate its citizens off the Diamond Princess. CDC Statement.

Feb. 15, 2020: Pompeo, Motegi, and South Korean Foreign Minister Kang hold a trilateral meeting on the sidelines of the Munich Security Conference in Germany.

Feb. 17, 2020: Two charter flights carrying passengers from the Diamond Princess depart Tokyo for the United States.

Feb. 17, 2020: Emperor of Japan cancels his birthday celebration.

Feb. 18, 2020: Japanese epidemiologist Iwata Kentaro (Kobe University) posts a YouTube video criticizing unacceptable quarantine practices onboard the Diamond Princess.

Feb. 19, 2020: Disembarkation begins for passengers confirmed as not being infected on the Diamond Princess.

Feb. 24, 2020: White House asks Congress for $1.25 billion in emergency funds to fight COVID-19.

Feb. 27, 2020: Abe asks all elementary, junior high, and high schools nationwide to close through the end of spring break in early April.

Feb. 28, 2020: Princess Cruises reports that all guests have disembarked from the Diamond Princess.

Feb 28, 2020: Governor of Hokkaido Naomichi Suzuki declares a state of emergency over coronavirus.

March 1, 2020: Final Diamond Princess crew members disembark from the cruise ship.

March 3, 2020: CDC lifts all federal restrictions on testing for COVID-19.

March 5, 2020: Japanese government announces postponement of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Japan.

March 6, 2020: A report by SMBC Nikko Securities Inc. projects that cancelling the Olympic Games will reduce Japan’s annual GDP by 1.4%.

March 6, 2020: United States enacts an emergency spending package to combat the spread of COVID-19.

March 9, 2020: Japan implements two-week quarantine and travel restrictions for visitors from China and South Korea.

March 10, 2020: Japan adopts a 1 trillion yen ($9.6 billion) stimulus package to help businesses affected by the COVID-19 outbreak.

March 13, 2020: Trump declares national emergency over the COVID-19 outbreak.

March 13, 2020: Pompeo and Motegi hold a US-Japan Summit Telephone Talk on COVID-19.

March 13, 2020: Japan revises existing law to allow Abe to declare a state of emergency for the COVID-19 outbreak.

March 16, 2020: Trump and Abe attend G7 Summit by video conference. Leaders’ Statement.

March 20, 2020: Motegi and Pompeo speak by telephone about COVID-19.

March 22, 2020: Canada announces that it will not attend the Olympic Games in Tokyo.

March 23, 2020: Australia announces that it will not attend the Olympic Games in Tokyo.

March 23, 2020: United States and Japan expand access for US and Japanese air carriers to fly between the United States and Tokyo’s Haneda airport.

March 24, 2020: Japan and the International Olympic Committee agree to postpone the Olympic Games until 2021.

March 25, 2020: Trump and Abe speak by telephone about the Tokyo Olympics and COVID-19.

March 26, 2020: First US Forces Japan active duty member tests positive for COVID-19.

March 26, 2020: Pompeo and Motegi attend the G7 Foreign Ministers’ Meeting by video conference.

March 26, 2020: Japan enacts entry restrictions on travelers from the United States.

March 26, 2020: Trump and Abe attend the G20 Summit by video conference.

March 27, 2020: Trump signs a $2 trillion stimulus package into law in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

March 31, 2020: A letter from Capt. Brett Crozier, captain of aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt, to Navy officials pleading for help with COVID-19 cases aboard his ship is published by the San Francisco Chronicle.

April 1, 2020: Abe announces plan to send two masks to every household amid growing concerns over shortages.

April 5, 2020: Capt. Crozier is removed from command of the USS Theodore Roosevelt.

April 6, 2020: Abe declares a state of emergency over COVID-19 for one month beginning April 7 in Tokyo, Osaka, Kanagawa, Saitama, Chiba, Hyogo, and Fukuoka prefectures.

April 6, 2020: US Forces Japan declares a public health emergency for the Kanto region.

April 6, 2020: Acting Secretary of the Navy Thomas Modly travels to Guam to explain his removal of Capt. Crozier to the crew of the USS Theodore Roosevelt.

April 7, 2020: Modly resigns as Acting Secretary of the Navy.

April 14, 2020: Trump announces that he will cut off funding for the World Health Organization (WHO) over its response to COVID-19.

April 15, 2020: US Forces Japan declares a Japan-wide public health emergency.

April 16, 2020: Abe and Trump attend the G7 Summit by video conference.

April 16, 2020: Abe declares nationwide state of emergency.

April 17, 2020: Trump encourages protests against social distancing restrictions in some US states.

April 20, 2020: Trump announces plan to suspend immigration to the US.

April 24, 2020: Navy officials recommend the reinstatement of Capt. Crozier.

May 4, 2020: Abe extends the state of emergency until May 31.