Articles

Southeast Asia was the center of international attention in November as regional and global leaders gathered at the G20 conference in Indonesia, which took place between the annual ASEAN-hosted summit meetings in Cambodia and the yearly APEC leaders meeting in Thailand. Acute China-US rivalry loomed large in media and other forecasts, warning of a clash of US-Chinese leaders with negative implications feared in Southeast Asia and elsewhere. The positive outcome of the Biden-Xi summit at the G20 conference and related actions eased tensions, which was welcomed, particularly in Southeast Asia, but the implications for the US and allies’ competition with China remain to be seen. Tensions over disputes in the South China Sea continued unabated. President Xi Jinping made his first trip to a major international gathering at the G20 conference followed by the APEC meeting after more than two years of self-imposed isolation in line with his government’s strict COVID-19 restrictions.

His visit occurred against the background of China’s unprecedented military show of force in response to US advances in relations with Taiwan, strident criticism of US efforts to increase influence in Southeast Asia and elsewhere, and remarkable warnings about China’s determination to resist adverse international threats in his landmark report to the 20thCommunist Party Congress in October validating his third term as party leader. Representing the United States at the ASEAN and G20 summits, President Joseph Biden gave no ground on Taiwan or other sensitive issues, increased US support for the island government, signed two massive bills calling for over half a trillion dollars of spending to compete with China on high technology and climate change, and imposed strict export controls on advanced computer chip technology to undermine China’s high technology ambitions.

Because of protocol and scheduling, Xi and Biden overlapped only at the G20 meeting, making the Xi-Biden summit meeting on the sidelines of that conference a focus of attention. As discussed in the US-China chapter of this edition of Comparative Connections, Xi adopted a more moderate approach in dealing with the United States. He notably ended China’s past insistence that the United States change its policies toward China before China would agree to the Biden government’s longstanding request to work with China to set guardrails to manage US-China rivalry in ways that would avoid military conflict. The Chinese leader’s new approach was accompanied by public diplomacy efforts that were remarkable because they were starkly contrary to Chinese diplomacy throughout 2022. Chinese representatives and commentary endeavored to persuade audiences in Southeast Asia and elsewhere that Xi’s report and recent strident Chinese commentary and provocative actions did not represent China’s intentions. They corrected such “misperceptions” and advised that Chinese intentions were moderate, accommodating, and positive, focused on constructive outreach for cooperation in Southeast Asia and elsewhere. In addition to the United States, targets for this call to improve ties included US allies and partners heretofore strongly criticized by China for their policies in Southeast Asia and elsewhere, notably Japan and Australia.

Biden vs. Xi: Assessing Competition for Prominence

Chinese media devoted enormous publicity to Xi’s activities, emphasizing Beijing’s new depiction of China’s positive intentions and outreach for the benefit of the world. In Southeast Asia there was debate on the causes of China’s new flexibility. One cause was seen as the failure of China’s tough approach to the US on Taiwan and other sensitive issues to lead to US concessions, resulting in an increasingly dangerous situation with serious negative regional and global implications. China’s position on support for Russia in the war in Ukraine had increasing negative implications for Chinese influence abroad. Beijing’s heretofore strict “zero-COVID” restrictions leading to mass protests and economic decline also were seen in need of change. The salience of climate change at the summits and in Southeast Asia in particular, followed the COP-27 meeting in Egypt, where Biden asserted world leadership amid China’s neglect and serious shortcomings as the world’s leading emitter of greenhouse gases increasingly relying on coal as China’s main source of energy. The new Chinese flexibility was seen to help mitigate these negative developments impacting Beijing in the US-China rivalry for influence in Southeast Asia and globally.

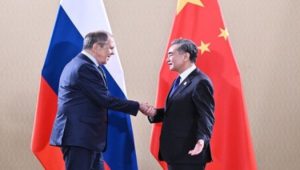

Figure 1 Foreign Minister Wang Yi meets with Russian counterpart Sergey Lavrov in Bali, Indonesia. Photo: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China

Recent circumstances hampering China and favoring the US in their rivalry also included the Biden government’s leadership in creating a broad and growing international coalition countering Russian aggression in Ukraine and dealing with related energy, food, and economic issues. The salience of these problems at the summits in Southeast Asia cast an ever more critical light on China’s wide-ranging support for Vladimir Putin, including strong Chinese pressure on world governments to not side with the US in supporting Ukraine and criticizing Russia.

Adding to the mix was Biden’s advantage as an experienced, collaborative, consultative, and accommodating leader in building coalitions to deal with international problems. This talent was on display as the US president convened and consulted closely with leaders in an emergency meeting of the G7 and with NATO members during the G20 summit over a missile strike in Poland.

Biden had an advantage in having built personal rapport in often-repeated in-person meetings with most of the G20 leaders. He showed flexibility in considering opposing positions of leaders such as Turkey’s Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, and even engaging in substantive discussion with authoritarian leaders in Egypt and Cambodia. In contrast, Xi Jinping came to the summits in Southeast Asia with little in-person contact with most leaders over the past three years. His message of struggle and resolute resistance at the party congress and firm Chinese policies on COVID restrictions and economic self-reliance underlined a rigid and uncompromising image reinforced by Xi’s aloof and sometimes stern personality. Chinese media said that Xi actively “worked the room” in interactions with foreign leaders at the G20 but he reportedly skipped the Indonesian leader’s “bonding” experience for the visitors in dressing up in matching outfits to plant trees in a nearby forest park, and his schmoozing at the conference included a widely publicized unpleasant encounter with the Canadian prime minister and a snub of the British prime minister.

Figure 2 President Jokowi invites G20 leaders to Ngurah Rai Forest Park, Bali. Photo: BPMI of Presidential Secretariat

The summit participants’ widespread concern with climate change allowed Biden to play a leading role at the COP-27 summit given passage in August of the Inflation Reduction Act, which has $369 billion for climate change efforts. In contrast, Xi Jinping was notable for not attending the summit, and in recent months China blocked climate change talks with the US until the US met Chinese preconditions.

One final area at the summits of importance to Southeast Asia that advantaged the United States in the competition with China was the Biden government’s correction of the enormously damaging Trump government’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic. Effective use of advanced vaccines and providing expert public health guidance worked along with the weakened potency of the virus in an increasingly immune US population. This allowed for a return to economic and social normalcy, notably raising the influence and attractiveness of the US economy and society. By contrast, China’s well-justified pride in 2020 in avoiding the death rate in the United States seemed much less important as international attention focused on Beijing’s continuing isolation and the rigid zero-COVID lockdowns that harm the economy; the problem was that halting the zero-COVID policy could result in a wave of fatal illness among poorly vaccinated elderly people in particular.

China Strengthens Regional Ties

At the three summits in November, Chinese leaders and commentary stressed China’s strong economic position and attentive diplomacy with Southeast Asian and other developing countries, notably the respective hosts, Cambodia, Indonesia, and Thailand.

Premier Li Keqiang’s six-day visit to Cambodia beginning Nov. 8 involved attending the 25th China-ASEAN Leaders Meeting; the annual ASEAN +3 meeting that included China, Japan, and South Korea; the 17th East Asian Summit; and an official visit to Cambodia. Routine Chinese commentary depicted China-ASEAN ties as exceptional in Chinese foreign relations, said to be “the most dynamic, substantive and mutually beneficial.” China’s largest trading partner for the past two years, China trade with ASEAN amounted to a record $798 billion in the first 10 months of 2022, a 13.8% increase over the previous year. Two-way investment amounted to $340 billion, with 2021 Chinese investment in ASEAN amounting to $14.35 billion and ASEAN investment in China amounting to $10.58 billion. Chinese commentary highlighted the China-ASEAN Joint Statement on Strengthening Common and Sustainable Development which together with another joint statement marking the one-year anniversary of the Chinese-ASEAN Comprehensive Strategic Partnership will guide China-ASEAN future relations. Negotiations were launched on a new “3.0” version of the ASEAN-China Free Trade Agreement. Premier Li welcomed the China-ASEAN statement commemorating the 20th anniversary of the Declaration on the Conduct of the Parties in the South China Sea and pledged China would work with all ASEAN countries for peace, friendship and cooperation in the South China Sea.

Figure 3 Leaders attending the 25th China-ASEAN Summit pose for a photo in Phnom Penh, Cambodia on Nov. 11, 2022. Photo: Xinhua

In an allusion to the United States and the South China Sea disputes, coverage of the ASEAN+3 summit featured Chinese warnings against unnamed forces sowing discord among regional countries for their own narrow interests.

An authoritative wrap-up of Xi Jinping’s participation in the summits in Indonesia and Thailand and his official visit to those countries said he had “close to 20 bilateral talks” with international leaders, including Biden, It judged that Xi’s speeches and diplomacy showed the correct direction for global governance, expanded China’s global partnerships, and steadied relations with the United States. Foreign Minister Wang Yi summarized the trip by emphasizing Xi’s support for developing countries and a list of 15 projects he proposed at the G20 involving cooperation and sustained multilateralism.

Wang also highlighted Xi’s meeting with Vice President Kamala Harris, who represented the United States at the APEC meeting, expressing hope that the two countries would “reduce miscalculations and misjudgements and jointly push for bilateral ties to return to the track of healthy and stable development.” Wang also highlighted talks between the US Treasury secretary and the US special trade representative with their Chinese counterparts as important as the two countries try to prevent relations from getting off course and seek to find the right way to get along. Xi’s speech at the G20 criticized—without mentioning—US efforts to politicize food and energy issues, draw ideological lines, promote group politics and bloc confrontation, and use export controls against other countries.

Figure 4 Xi Jinping walks to the venue of the 17th summit of the Group of 20 in Bali. Photo: Ju Peng/Xinhua

Subsequently, the Chinese foreign minister’s authoritative annual review of Chinese foreign relations in a speech on Dec. 25 viewed relations with ASEAN positively among the top five Chinese priorities and called for quickening the pace of China-ASEAN consultations on the proposed South China Sea Code of Conduct.

On bilateral matters, Chinese commentary highlighted trade with Indonesia amounting to $124 billion in 2021, a growth of 60% over the previous year. Chinese investment in Indonesia was the second largest among ASEAN states. Important Belt and Road Infrastructure projects, notably the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railroad project, were highlighted as was China’s provision of 280 million vaccine doses to Indonesia. In Thailand, Xi emphasized a “special bond” with Thailand and said that China considered Thailand and China as “one family.” Strong economic ties including large infrastructure projects were highlighted with Xi calling for speeding up China-Thailand-Laos railway connections. In Cambodia, Chinese commentary hailed major infrastructure projects, with Premier Li and Prime Minister Hun Sen presiding at the opening of a Chinese-built expressway from the capital to the country’s main port.

China-Vietnam Summitry: Stabilizing Ties

Chinese President Xi Jinping greeted visiting Vietnamese leader and general secretary of the Vietnamese Communist Party Nguyen Phu Trong on Oct. 31. Trong’s visit was the first by a foreign leader since Xi secured an unprecedented third term as China’s top leader at the Chinese Communist Party’s 20th party congress in October 2022. In the high-profile visit, Xi indicated that both countries share strong foundations for a close partnership, emphasizing that they should “never let anyone interfere” with the progress of their domestic agendas in forging a strong socialist agenda for progress and development. Like Xi, Trong has also expanded his power base and authority within Vietnam’s political system, staying on as Vietnamese Communist Party general secretary beyond the usual tenure of one to two terms. During the bilateral summit, both leaders pledged to expand security and economic partnership, including focusing on building a “stable industrial chain and supply chain system.” Other highlights of the talks included an agreement to “properly manage” their differences and maintain regional stability in the South China Sea.

Laos: Leader Visits Xi Amid Serious Economic Troubles

Following the example of Communist Party leaders from Vietnam and Cuba, Laos President and Communist Party leader Thongloun Sisoulith traveled to Beijing, meeting Xi Jinping on Nov. 30 to congratulate him on being selected once again as Chinese Communist Party leader. The meeting came amid foreign reports over the past year of Laos government’s dire fiscal situation as a result of massive Chinese debt estimated by the Thayer Consultancy to be about $14 billion—against reserves of about $1.3 billion. China accounts for about half of Laos’ foreign debt, with the majority caused by expenses associated with the multibillion-dollar China-Laos railway. The railway is an important link for China’s ambitions to connect southwestern China with the center of the Southeast Asian peninsula all the way to Singapore. China Daily routinely runs stories about the success of the railway, offering figures of cargo and passenger traffic but Chinese publicity avoids the discussion in foreign outlets about the limited benefits for Laos, which are insufficient to pay off the massive loans that allowed the railroad to be built. Chinese media coverage of the Lao leader’s meeting with Xi only alluded to the debt problems with Xi saying in passing that China will continue to provide assistance to relieve the difficulties Laos is facing but without mentioning the railway debt.

Philippines: China Cautious, Wary of Marcos’ US Cooperation

Expert foreign and Philippine commentators continue to differ in assessing how recent activism in US-Philippines military relations and top leaders’ meetings will shape US-Philippine relations in the face of opposition by China. Senior US-Philippines military meetings promised big increases in joint exercises in 2022. Substantial increases were forecast in US military rotational deployments to the country, military aid, assistance in maritime surveillance capacity, and countering illegal fishing. Bases for US deployments include sites in sensitive locations facing areas in the South China Sea contested by China. President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. reportedly was very welcoming of closer security ties with the United States in meetings with President Biden at the United Nations in September and with Vice President Harris in Manila in November. Harris traveled to one of the base sites facing Chinese-claimed waters and, without mentioning China, registered strong backing for Philippine allies in the face of outside pressures.

Figure 5 US Vice President Kamala Harris delivers a speech on board a Philippine coastguard vessel in Puerto Princesa, Palawan. Photo: Reuters

The sharp uptick in regional tension following China’s dramatic use of force against Taiwan in August reportedly prompted greater Philippines interest in working with the United States in dealing with a possible Chinese attack on Taiwan and in demonstrating resolve to deter China from such action.

Official Chinese commentary on these developments highlighted limits on the US-Philippines cooperation because of what Chinese observers saw as strong Philippine interest in closer ties with China and disadvantages of close alignment with Washington. Recounting Xi Jinping’s meeting with Marcos during the APEC leaders meeting in Bangkok, one report said the two leaders discussed extensive economic contacts and agreed that maritime disputes “should not define the entire Philippines relationship.”

Chinese commentary at the start of Marcos’ first official visit to China that began Jan. 3 was positive. The results of the visit may clarify where the new president stands in the US-China rivalry. An up-to-date assessment of Philippine leaders’ calculations amid growing China-US rivalry highlighted state and military officials, public opinion, and many business interests as broadly pro-US and suspicious of China. But other leaders distrust the US government and view the alliance as destabilizing and an unneeded source of tension with China. Parts of the country that have benefited from China’s economic involvement also tend to favor China, including areas long ruled by the Marcos family.

Continued Military Tensions in the South China Sea

Resumed US-China military talks following the Xi-Biden summit in Indonesia featured talks between Chinese Defense Minister Wei Fenghe and US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin on the sidelines of the ASEAN nations and dialogue partners defense ministers’ meeting in Cambodia on Nov. 22. Chinese media criticized Austin for raising prominently his concern with “the increasingly dangerous behavior” of Chinese warplanes in the Indo-Pacific region, increasing the risk of an accident.

On Nov. 29, a US cruiser conducted the first freedom of navigation operation in the disputed South China Sea following the Xi-Biden summit, prompting strong criticism from the spokesman of China’s Southern Theater Command and a prompt reply from a representative of the US 7th Fleet.

China was not directly involved in a public dispute between the foreign ministries of Vietnam and Taiwan over Vietnam’s complaint about a live-fire Taiwan navy drill on Nov. 29 near Taiping Island, the largest natural land feature in the Spratly Islands of the South China Sea. The island is claimed by Vietnam and China, but has long been controlled by the government in Taiwan. The Taiwan exercise was seen as countering possible threats from Beijing, not Hanoi.

Philippines’ disputes with China in the South China Sea in November involved a Chinese Coast Guard vessel forcibly seizing rocket debris assumed to be from a Chinese rocket launch that was detected and was being towed by Philippine servicemen at the small outpost at Second Thomas Shoal. The Philippines’ complaints over the incident added to the 193 note verbales issued by Manila over Chinese provocations in the South China Sea in 2022.

The Chinese Embassy in Manila strongly disputed a US State Department statement on Dec. 19 supporting the Philippines government in the face of Chinese coercive malfeasance on two matters: 1) A large Chinese Coast Guard ship blocked and harassed a small Philippines supply ship trying to reach the Philippines military outpost on Second Thomas Shoal, and 2) Employing “swarms” of fishing boats including China’s Maritime Militia to establish control over disputed South China Sea land features. The boats later were reported to be involved in seabed dredging to expand the size of the locations, recalling Beijing’s larger-scale island building a few years ago. Relatedly, the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative reported that Vietnam had created 1.7 sq km of land among the features it controls in the Spratly Islands during the second half of 2022.

Reinforcing Secretary Austin’s concerns in talks with the Chinese defense minister in November, the Indo-Pacific Command released a statement on Dec. 29 sharply critical of an incident on Dec. 21 when a Chinese jet fighter harassed a US reconnaissance plane over the South China Sea and came within 20 feet of the much larger US aircraft, forcing it “to take evasive measures to avoid a collision.” A video of the incident also was released. On Dec. 30, the Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson criticized the US account and on Dec. 31 China’s Southern Theater Command spokesperson rebutted the US charges saying that it was the US plane that made a dangerous maneuver that threatened the Chinese fighter aircraft. A Chinese video of the incident also was released.

China-Myanmar Relations

In response to continued unrest and tensions in Myanmar, the UN Security Council approved its first-ever resolution on Myanmar on Dec. 21, calling for an immediate end to violence and urging its military rulers to release all “arbitrarily detained” prisoners including ousted leader Aung San Suu Kyi. The Security Council approved the resolution, with China, Russia, and India abstaining. The latest development comes on the heels of regional frustration over the lack of progress in Myanmar’s implementation of ASEAN’s plan that junta leaders agreed to in April 2021. During ASEAN summitry in November 2022, regional leaders indicated that they wanted a specific timeline for Myanmar’s junta leaders to implement the peace roadmap. Until substantive progress has been made, ASEAN would maintain its ban on Myanmar military-affiliated officials from attending gatherings of the regional bloc. ASEAN leaders also emphasized that they would explore “other approaches” to incentivize change in Myanmar’s behavior.

Earlier this year, ASEAN foreign ministers engaged Beijing to support the region’s diplomatic efforts in Myanmar. China maintains that it would like to see stability restored in Myanmar, while refraining from directly criticizing the military junta’s actions. Stressing that China’s “policy of friendship towards Myanmar is for all its people,” China’s UN Ambassador Zhang Jun said “there is no quick fix” to the crisis, which requires patience, time, and pragmatism for all parties and factions in Myanmar to pursue dialogue and reconciliation. Zhang maintained Beijing’s support for ASEAN’s diplomacy and for Southeast Asian leaders to forge consensus in managing and resolving the crisis.

In a separate but related issue, local reports indicated that bomb explosions, caused by Myanmar military’s firing mortar shells at Rohingya refugees fleeing into Bangladesh, reduced after the Chinese government was informed of the explosions. According to Bangladesh’s Foreign Minister AK Abdul Momen, the explosions along the Myanmar border with Bangladesh abated after his ministry informed Chinese counterparts. Bangladesh also asked for Chinese assistance in relocating more than 5,000 Rohingya to Myanmar. While the extent of China’s intervention remains unclear, regional expectations of Beijing’s involvement to help stabilize the Myanmar crisis will continue to build.

Assessing China-US Competition in Southeast Asia

Major US studies in the second half of 2022 came to somewhat different conclusions about the state of China-US competition in the region. A Council on Foreign Relations report compared a deteriorating Chinese position over the past five to seven years with what it saw as high points of Chinese positive image and influence in Southeast Asia in the 1990s and early 21st century. The advances were brought about by effective use of soft power initiatives, nuanced promotion of China’s development model, increased aid outflows, support for ethnic Chinese in regional countries, and modest and relatively humble diplomacy. The collapse came because of rising Chinese authoritarian rule at home, rigid COVID-19 regulations isolating China, assertive actions on regional disputes, harsh treatment of dissent in Xinjiang and Hong Kong, and assertive wolf warrior diplomacy, all of which offset the billions of dollars the Chinese government spent to promote a positive image in world affairs. In Southeast Asia, the study highlighted a 2022 Institute of Southeast Asian report which showed a remarkably high level of suspicion and worry among Southeast Asian elites over possible Chinese dominance of the region.

An Asia Society report on Chinese diplomacy in Southeast Asia was more positive, concluding that long-term trends favored continued increase of Chinese influence in Southeast Asia relative to other major partners. It argued that what it called a creeping trend of accommodation of China’s interests could see Beijing wield a stronger veto power in the region, blocking advances in Southeast Asia’s relations with the United States, Japan, and Australia.

In a recent report issued by the Center for Asia and Globalization of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore, key findings reflected the view that Southeast Asian states prefer to avoid becoming entangled in the US-China power play and competition. The report examined how countries in the region might respond to a crisis in the Taiwan Strait or East China Sea, and the conditions under which the region is more or less likely to engage in these conflicts. Analysis from the comprehensive study indicates that “Southeast Asian elites are fully cognizant of the consequences of a conflict in the East China Sea or across the Taiwan Strait, but they are reluctant to take active measures to prevent conflict and are unlikely to respond forcefully if conflict erupts.” It reinforces the view that the region, especially Southeast Asia, continues to emphasize pragmatic engagement with all major powers, including the United States and China, and prefers expanding trade and economic ties that would help increase development and stability within and across the region. The report further concludes that “US [policymakers] lack appreciation for the depth of Southeast Asian preferences for nonalignment, high tolerance for inaction, and disinterest in having agency or taking overt measures to prevent a conflict around Taiwan and the East China Sea.”

Pacific Islands: Low-Keyed Chinese Criticism of US Initiatives

Chinese officials remained largely mute about the Pacific Islands and official Chinese commentary was limited. An exception was Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s Dec. 25 speech on accomplishments in 2022, which briefly highlighted purported major progress made during his whirlwind visit to the region in May. China’s low public posture has prevailed since the setback during Foreign Minister Wang’s tour: he sought to persuade island governments on short notice to endorse a Chinese-drafted common regional agreement with China involving sensitive security and other issues, and failed. This initiative came in the wake of China’s successful security agreement with the Solomon Islands in April. China’s ambitions prompted strong US-led efforts to counter China in the region. They involved a summit in Washington of Pacific Island leaders, a formal US strategy for the region, a roadmap for a whole-of-government US-Pacific Island partnership in the 21st century, and establishment of the Partners in the Blue Pacific initiative involving Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and the United Kingdom as well as the US, and focused on development assistance in the region. Public Chinese government responses to these measures was limited to low-level official Chinese commentary criticizing each of the moves as discriminatory against China and not in the overall interests of island nations.

Outlook

Southeast Asian nations will watch carefully how the Chinese and US governments manage tensions amid continued rivalry following the Xi-Biden summit. Since both powers are deeply involved in regional matters, this could lead to positive initiatives from Washington and Beijing to attract ASEAN and its members. But coercive and disruptive great power competition could occur in ways that adversely affect the interests ASEAN and its members, which regional powers have little ability to control.

Sept. 6, 2022: China and Thailand conclude “Exercise Falcon Strike,” an 11-day joint air force exercise in northeast Thailand. The drill focuses on deepening practical cooperation and involves deployment of some of China’s latest air force assets, including a JH-7AI fighter-bomber, six J-10 fighter jets, and KJ-500 airborne early warning aircraft. The timing of the exercise coincided with another regional military drill, “Super Garuda Shield,” hosted by the United States and Indonesia and involves a dozen other countries including Japan, Australia, and Singapore.

Sept. 16, 2022: The 19th China-ASEAN Expo convenes in Nanning, Guangxi, in China. The four-day trade expo seeks to promote regional business and economic cooperation between China and ASEAN. More than 1,000 companies and enterprises from around the region registered to take part in the annual trade fair.

Oct. 30-Nov. 2, 2022: Chinese President Xi Jinping hosts Vietnamese leader and General Secretary of the Vietnamese Communist Party Nguyen Phu Trong. During their summit, both leaders pledge to expand security and economic partnership, including focusing on building a “stable industrial chain and supply chain system.” Other highlights of the talks include an agreement to “properly manage” differences and maintain regional stability in the South China Sea.

Nov. 1-2, 2022: Chinese Vice Premier Han Zheng visits Singapore for the 18th Joint Council for Bilateral Cooperation. The two sides sign 19 memorandums of understanding and agreements on issues ranging from public health, tourism exchanges, green financing and development, e-commerce, and innovation cooperation. China and Singapore also agree to speed up negotiations on the China-Singapore free trade agreement and move forward on implementing the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, the world’s largest trade agreement that went into effect in 2022.

Nov. 9, 2022: Chinese Premier Li Keqiang visits Cambodia for a six-day visit and delivers a development assistance package of nearly $30 million while signing 18 agreements on bilateral aid and cooperation on agriculture trade, infrastructure development, public health, and education projects. Following his state visit to Cambodia, Li will stay on for a series of ASEAN meetings with regional leaders.

Nov. 14, 2022: Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs clarifies that China’s aid to expand and upgrade Cambodia’s Ream Naval base reflects a “normal activity of providing assistance,” and refutes media reports that the activities are targeted at any third party.

Nov. 18, 2022: President Xi arrives in Bali and holds talks with Indonesian counterpart Joko Widodo. They agree to expand infrastructure and maritime cooperation and deepen “strategic coordination” in regional affairs, especially with regard to building synergy between China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Indonesia’s Global Maritime Fulcrum, Jakarta’s vision to turn the country into a global maritime hub. Xi is in Bali to attend the Group of 20 summit, meeting other world leaders, including US President Joe Biden.

Nov. 20, 2022: Philippine Navy rubber boats and Chinese Coast Guard inflatable boats engage in an encounter concerning rocket debris that the Philippine Navy found floating off the coast of Thitu Island in the Spratlys. The Chinese Coast Guard crew members were seen cutting the towing line the Philippine Navy officers had placed to retrieve the rocket debris.

Nov. 24, 2022: 9th ASEAN Defense Ministers’ Meeting-Plus (ADMM-Plus) convenes in Siem Reap, Cambodia, where regional defense chiefs adopt a joint declaration to promote peace and security in the region. The declaration reaffirms the ADMM-Plus countries’ commitment to promoting regional stability by reinforcing strategic trust and mutual confidence.

Nov. 26, 2022: Malaysia’s new prime minister, Anwar Ibrahim, says he will continue to maintain stable ties with China as he seeks to emphasize economic engagement, while avoiding confrontation on contentious issues. When asked to comment on how his government will manage foreign policy issues, Anwar indicates that he would continue to pursue positive and pragmatic ties with the United States and China.

Nov. 30, 2022: Laotian President Thongloun Sisoulith visits Beijing and meets his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping. The two heads of state agree to deepen bilateral ties in the areas of law enforcement, and defence cooperation, as well as economic, trade, and investment exchanges.

Dec. 8, 2022: A senior Philippine foreign affairs official shares that ASEAN member states and China are negotiating the Code of Conduct in the South China Sea “very seriously, very delicately,” with the conclusion of the second reading of the document in sight. Noel Novicio, Philippines’ Deputy Assistant Secretary for Foreign Affairs and Executive Director for ASEAN Affairs, cautions that in spite of the progress, the final text and substantive aspects of the Code of Conduct remain far from being finalized.

Dec. 16, 2022: Philippines lodges formal complaints against and criticisms of China’s latest incursions in the South China Sea, during which Chinese vessels entered disputed waters around the Iroquois Reef and Sabina Shoal in early December, just weeks after an encounter between the Philippine Navy and the Chinese Coast Guard.

Dec. 29, 2022: President of the Philippines Ferdinand Marcos Jr. announces that he will visit China in early January 2023 amid tension and disputes in the South China Sea. The Philippines Department of Foreign Affairs announces that during the visit, both sides will sign an agreement to open direct communication lines and avoid tensions and accidents in the South China Sea.