Articles

The concert hall massacre near Moscow on March 22 was a source of shock and awe for Russia and the world. The incident, which resulted in the deaths of 144 people and 551 wounded, was the largest since the 2003 Beslan school siege (where more than 330 hostages died). Its timing cast a long shadow over major developments in the first few months of 2024, particularly the fifth term of President Vladimir Putin, who won 87.28% of the vote just five days prior. It also made any effort to end the two-year Ukraine war more difficult, if not impossible. As a result, much of China’s mediation 2.0 (March 2-12) was in parking mode. The Sino-Russian strategic partnership, too, was tested by two different priorities: Moscow’s need for more security coordination on one hand and China’s interest in stability in the bilateral, regional, and global domains on the other. Whatever the outcome, the stage was set for more dynamic interactions between the two large powers in the months ahead.

Normal Relations in Abnormal Times

Russia-China interaction was in “high-tempo” mode at the onset of 2024, as both sides adjusted to the new norm of a two-year war and persistent, albeit low-yield, peace efforts by China.

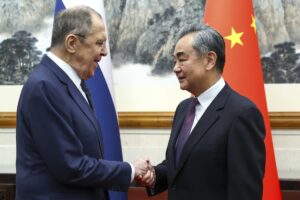

On Jan. 10, Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov initiated a phone conversation with Chinese counterpart Wang Yi. Several “priority items on the international agenda” were discussed, including the Ukraine war, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Korea, and the BRICS issues. In the age of “global geopolitical instability,” Lavrov and Wang noticed the “importance of Russian-Chinese strategic interactions” for “Eurasian security.”

2024 happened to be the 75th anniversary of the Sino-Russian/Soviet diplomatic relations and the commencement of the China-Russia Years of Culture (2024-25). For this, both sides were willing to enhance diplomatic coordination and high-level exchanges as they reviewed the schedule of these activities.

Beyond this, Wang reportedly said that “China firmly believes that Russia will be able to successfully complete its important domestic political agenda, and maintain national stability and development.” Lavrov, in turn, told Wang that “Russia firmly adheres to the one-China principle” when Taiwan’s 2024 presidential election was just 72 hours away and a high likelihood that DPP’s pro-independent candidate Lai Ching-te would win. Immediately after Lai’s victory, Russian Foreign Ministry Spokeswoman Maria Zakharova reiterated Russia’s “principled position” on the Taiwan issue.

A key issue in the Lavrov-Wang phone conversation was coordinating BRICS, which is chaired by Russia for 2024. In 2023, the group doubled its ranks by accepting five new members (Saudi Arabia, Iran, Egypt, United Arab Emirates, and Ethiopia) and more than 30 countries indicated interest in joining. Formed in 2006, BRICS has grown from a loose concept, coined by then Goldman Sachs Asset Management chairman Jim O’Neill for foreign investment strategies, into a thriving intergovernmental forum primarily for the Global South. Its more diverse matrix, however, means a more complex and challenging situation for internal cohesion and growing geopolitical constraints. Already the West had imposed heavy sanctions against some BRICS states (Russia and Iran) while becoming increasingly hostile toward the BRICS’ economic heavyweight (China). An enlarged BRICS would have to navigate between at least three vastly different sets of interests and goals: Moscow’s anti-West stance, India’s growing ties with the US-led Indo-Pacific strategic framework, and China’s “Community of Shared Future for Mankind” which aims to still work with the existing liberal international order.

Enter Dragon’s Year

February kicked off the Year of the Dragon, which is one of the 12 Chinese zodiac signs. The only imaginary animal symbol for the Chinese Lunar calendar, the dragon is anticipated to bring auspicious opportunities and exciting advancements for all. In his “extensive telephone conversation” with President Xi Jinping on the Chinese New Year’s Eve, Russian President Putin noted that the dragon represents wisdom and strength in Chinese culture (the Kremlin readout did not mention this).

The two heads of state discussed a range of global, regional, and bilateral issues, including the BRICS, SCO, Ukraine, and Israeli-Palistine conflicts. Satisfied with the Russia-China partnership, both vowed to work together for the 75th anniversary of Sino-Russian/Soviet diplomatic ties and the “Years of Cultural Exhanges” (2024-25) between the two nations. They “specifically stressed that close Russia-China interaction is an important stabilizing factor in world affairs.”

Putin reiterated Russia’s “one-China principle” regarding Taiwan. For Xi, the two sides should work hard to explore new areas of cooperation while maintaining existing production chains. Meanwhile, cultural/humanitarian exchanges needed to be both practical and sincere, leading to enduring people-to-people connections (连民心、接地气、有温度). The explosive growth of Chinese consumer products, particularly automobiles, in Russia following massive Western economic sanctions required both constant management and societal acceptance.

The Kremlin readout was brief about the Putin-Xi “extensive” phone talks. Seventeen hours later, the Kremlin released the full text of Putin’s interview with US conservative political commentator Tucker Carlson. Much of the two-hour interview was about Russia’s long and bitter history with the West, as well as the “sources” of the Ukraine conflict. Putin respectfully disagreed with Carlson’s “China threat” narrative also held by conservatives in America. Russia is used to coexisting with China, Putin remarked as he responded to Carlson’s claim that China was increasingly dominating the BRICS. “You cannot choose neighbors,” continued Putin. China’s foreign policy, however, “is not aggressive. Its idea is to always look for compromise.” And the US was “hurting itself” by limiting cooperation with China, according to Putin.

The Carlson interview was released on Chinese New Eve, when downtown Moscow kicked off a 10-day celebration (Feb. 9-18) featuring more than 300 separate events/shows as part of the Years of Culture of Russia and China in 2024-25. Chinese New Year became more popular among Russians despite the fact that there is not a Chinatown in Moscow, or in St. Petersburg, or anywhere else in Russia. Unlike almost any big city in the world, there are no “other” ethnic enclaves in Russian cities. The “broad celebration” of the 2024 Chinese New Year in Moscow was the first ever organized by Moscow’s authorities. Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova, whose 250-page doctoral thesis in Moscow’s People’s Friendship University was about Chinese New Year celebrations, joined Chinese Ambassador to Russia Zhang Hanhui in launching the 10-day festivity.

Figure 1 Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova and Chinese Ambassador to Russia Zhang Hanhui gesture during the celebrations of Chinese Lunar New Year’s Eve, Feb. 9, 2024 in Moscow. Photo: Contributor/Getty Images

Figure 2 This photo taken on February 9, 2024 shows Chinese Lunar New Year decorations on a street in Moscow, Russia. Photo: Xinhua/Bai Xueqi

The official promotion of the 2024 Year of the Dragon in Russia—shortly after two Russian New Year celebrations on Jan. 1 and 14—may add more elements of normalcy for Russians during a state of war de jure with the “collective West.” Beyond this, there were positive signs for the Russians at the onset of the Dragon Year. In 2023, Russia’s GDP increased by 3.6%, a sharp turnaround from the 1.2% loss in 2022 and outpacing the 0.5% growth of the EU. Meanwhile, Russia-China trade in 2023 hit a record $240 billion, a 26.3% increase from a year earlier.

MSC 2024: Wang Engaging the “Collective West”

The strategic town of Afdiivka in Donetsk Oblast, Ukraine was taken by the Russian forces on Feb. 17, 2024, after long and costly ground operations since October 2023 (“…a lot of blood has been shed” according to the Russian account). On the same day, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi said in his speech at the annual Munich Security Conference (MSC) that “China has never given up on promoting peace or slackened its efforts to facilitate talks.” Referring to President Xi Jinping’s “in-depth exchanges with…Russian and Ukrainian leaders,” Wang stressed that the “only one goal that China hopes to achieve…is to build consensus for ending the conflict and pave the way for peace talks.”

On the MSC sidelines, Wang Yi met Ukraine FM Kuleba at the latter’s request. The two “discussed “bilateral relations, trade, and the necessity of restoring a just and lasting peace in Ukraine,” according to the Ukraine sources. Wang reportedly told Kuleba that Beijing would remain neutral in the Russia-Ukraine conflict and not sell weapons to either side. “Even if there is only a glimmer of hope for peace, China will not give up its efforts,” Wang added.

Figure 3 Wang Yi Meets with Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba on Feb. 18, 2024. Photo: Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Figure 3 Wang Yi Meets with Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba on Feb. 18, 2024. Photo: Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs

The Wang-Kuleba talks were the first high-level meeting between the two sides since Ukrainian President Zelenskyy failed to schedule a meeting with Chinese Premier Li Qiang at the World Economic Forum in Davos (Jan. 15-19). Beijing also appeared uninterested in Ukraine’s invitation in late January for joining the Kyiv-sponsored Global Peace Summit in Switzerland. It was unclear if this caused the blacklisting of 14 Chinese firms on Ukraine’s “international sponsors of war” list, which led to China’s immediate demand for de-listing.

On Jan. 29, Ukraine’s ambassador to China Pavlo Riabikin requested a meeting with Chinese Vice FM Sun Weidong. The Chinese readout indicated that the two discussed the “Ukraine crisis and other issues of mutual interest and concern.” Riabikin reportedly told Sun that Ukraine attaches great importance to developing relations with China and stay committed to the one-China principle. Sun, in his turn, said that the two countries “should take a long-term view, respect each other and treat each other with sincerity to promote the steady and long-term development of bilateral relations.”

At least for China, the “Ukraine crisis”—a standard Chinese usage for the war in Ukraine—was not the only issue between Beijing and Kyiv. Despite the war, China continued to import large amounts of Ukrainian grain, sunflower oil, and iron ore (some 30% of Ukraine’s maritime exports were shipped to China). After a steep decline in bilateral trade in the first two years of the war (60% and 10.8% for 2022 and 2023 respectively), Chinese-Ukrainian trade volume in January-February 2024 grew by 46.6% year-on-year to $1.5 billion.

For Wang and other senior Chinese diplomats, the priority was to slow and/or reverse the escalation momentum of the two-year conflict when Western support to Ukraine became increasingly hampered by both domestic hurdles and the deficiency of the Western arms industry. Mixed messages from the West regarding Ukraine’s possible NATO membership, too, contributed to Kyiv’s increasing frustration. “We are confronted with a nuclear power. Either we will become a member of NATO, allied with a nuclear power, or we should restore our nuclear status,” Ukrainian lawmaker Oleksiy Goncharenko said during the MSC. In Munich, Wang Yi reiterated that nuclear weapons must not be used, nuclear wars must not be fought, and that all parties should work jointly to guarantee the security of nuclear materials and facilities. China, he said, “has honored its pledge and undertaken its international obligations in this regard.”

“Catch-24” (Уловка-24) Only for Russia?

It was unclear how Wang Yi’s reiteration of China’s minimalist nuclear posture (no-first-use) at the 60th MSC would impact the Ukraine conflict. Following his extensive diplomatic interaction with European counterparts in Munich and beyond (his subsequent official visits to France and Spain), FM Wang Yi was deeply impressed, if not shocked, by the growing pessimism in Europe regarding the prospects of both the Ukraine war and global system.

The post-MSC Europe, however, was torn by an even more alarming gap between unambiguous defeatism on the one hand and an initial but persistent call for direct NATO intervention in the Ukraine war on the other. Twice in late February (Feb. 26 and 29), French President Macron called for possible NATO’s direct presence in Ukraine. In testimony to the US House Armed Services Committee on Feb. 29, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin said (at 1:48:40…) that Russia and NATO could come into a direct military conflict if Ukraine fell. For these ominous signs of the “possibility of deploying NATO military contingents to Ukraine,” Russian President Putin explicitly warned in his Feb. 29 address to the Russian Federal Assembly that “[T]oday, any potential aggressors will face far graver consequences. They must grasp that we also have (nuclear) weapons—yes, they know this, as I have just said—capable of striking targets on their territory.” “Putin has never been so directly and so seriously talked about the possible use of nuclear weapons,” commented Hu Xijin, an influential media commentator in China.

The only remote glimpse of hope for an “end” of the two-year conflict was a column by Fyodor Lukyanov, editor-in-chief of the influential Russia in Global Affairs on Feb. 24. In the “How does the Russia-Ukraine conflict end?” titled by RT in the English translation two days later, Lukyanov pointed to a “package solution” of the conflict that Moscow “may have to face in the near future” even if “the pendulum has swung in Moscow’s favor and last year’s Western confidence has disappeared.” For Russia, this “very important moment” with both military and political dimensions meant a “Catch-24” (Уловка-24)—the original title of Lukyanov’s column—between various scenarios: freezing (suspension of hostilities), the West German scenario (NATO membership for Ukraine first and territorial recovery at the first opportunity), and a stable stalemate (a restrained Ukraine by its NATO membership not to provoke Russia), etc. None of these scenarios, however, were feasible for Russia now even if the Russian military had regained momentum in Ukraine. Indeed, Russia’s military success “may have the opposite effect of raising the stakes” for both sides. And the “hiccup” in US aid to Ukraine, once resolved, would lead to both a “quantitative and qualitative surge” of Western supplies, including more powerful long-range weapons for Ukraine. “The heat of the confrontation is already such that a further rise in temperature will bring it to a full boiling point, i.e. close to a direct confrontation between Russia and NATO,” warned Lukyanov.

Lukyanov’s “Catch-24” was predicted two months before by Professor Wan Qingsong, deputy director of Russia and Eurasian Institute at the East China Normal University in Shanghai. “Russia won’t easily freeze the conflict. Nor will it want to be ‘trapped’ in Ukraine.” To a large extent, this “to-be-or-not-to-be” dilemma may be a headache for all sides at the onset of the third year of the conflict: no one can win but no one can afford to lose. Hence a drift toward escalation.

Ambassador Li Hui’s Mediation 2.0

It was against this backdrop of an increasingly possible NATO-Russian direct confrontation that China’s Special Representative on Eurasian Affairs Li Hui traveled to Europe (Russia, Poland, Ukraine, Germany, and France) on March 2-12 for his second round of talks on the peaceful settlement of the Ukraine conflict.

In Moscow, Li had “an in-depth exchange of views” on the evening of March 2 with Russian Deputy FM Mikhail Galuzin. “Any conflict in the end has to be settled through negotiations. The more acute the conflict is, the more important it is not to give up efforts for dialogue,” Li stated in the meeting. Galuzin reportedly agreed. He nonetheless stressed that “any discussion of the settlement in Ukraine is impossible without Russia’s participation and taking into account its security interests.”

In his six-hour stay in Kyiv (due to “train schedule problems”) on March 7, Li held “frank and friendly talks” with President’s Office Head Andriy Yermak, First Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Economy Yulia Svyrydenko and Minister of Foreign Affairs Dmytro Kuleba. Unlike the broad topics (Russian participation in peace talks) discussed in Moscow, Li’s talks with Ukrainians were packed with specific issues ranging from the battlefield situation, the work of the black Sea grain corridor, POW, Kyiv’s peace formula, and preliminary work for the Switzerland peace summit. Li was also asked to assist Ukraine in several key issues, including the return to Ukraine of the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, nuclear safety, alleged Ukrainian children taken to Russia, etc. Li’s group was also shown fragments of North Korean missiles and other weapons from third countries. It was unclear if these arrangements were part of the preconditions for starting a negotiated piece or issues that would be eventually addressed during and after a negotiation. “We value our partnership with China and hope that today’s talks will be another step towards deepening and strengthening our relations,” Yermak reportedly told Li.

Three days after the end of his shuttle mediation in Europe, Li Hui returned to Moscow as head of China’s delegation to observe Russia’s presidential election on March 17. In a meeting the day after the election, Li briefed Foreign Minister Lavrov about his European tour. Lavrov reaffirmed that Russia was “open to a negotiated solution.” Moscow, however, would not take part in any events on the so-called “Zelenskyy formula.” And any “negotiating process needs to be preceded by the elimination of Kyiv’s self-ban on talks with Moscow, the cessation of arms supplies, and a clear signal of a willingness to consider current realities and Russia’s lawful interests,” said Lavrov. It was unclear if Lavrov’s strong wording related to Putin’s post-election statement that Russia planned to create a “buffer zone” against Ukraine’s long-range strikes and cross-border raids. A more confident Putin, and Russia, appeared less likely to compromise.

In a briefing to diplomatic envoys stationed in China from 78 countries on March 22, Li expressed pessimism about any ceasefire or ending the conflict. Instead, “the danger of further escalation is increasing,” warned Li. There was also a huge gap regarding the peace negotiations, said Li. All parties, however, appreciated China’s efforts for a greater constructive role and said China could—as “a common friend” of both Russia and Ukraine—facilitate communication and consensus building toward peace talks, recalled Li.

As to China’s absence from international conferences on the Ukraine issue after the August 2023 Jeddah conference in Saudi Arabia, Li stated that China supported the timely convening of an international peace conference recognized by both Russia and Ukraine, with equal participation by all parties, and fair discussion of all peace proposals. The goal of such a conference had to be result-oriented, not to support or oppose any side, stressed Li.

March: Putin’s Fifth Term and the Moscow Terror Massacre

Li Hui’s briefing in Beijing was attended by both Russian and Ukrainian diplomats, a rare occasion when the two warring parties were together in the same room. Li also chose the occasion to clarify any “fallacy” regarding problems in China’s relations with Ukraine. “In my talks (in Kyiv), the Ukrainian side refuted the fallacy that ‘China deliberately alienates Ukraine,’ emphasized that China-Ukraine relations have not been affected by the crisis, and expressed its appreciation of China’s balanced stance on the crisis,” stated Li.

Beijing’s friendly gesture toward Ukraine was soon overtaken by events. Just a few hours later, Moscow, and the world, were shocked by the terror attack at the Crocus City Hall music venue in Krasnogorsk, Moscow Oblast, Russia. The attack killed 144 people and injured 551, according to Russian authorities at the end of March, making it among the worst terror attacks in Russia’s post-Soviet history.

Immediately after the attack, ISIS claimed responsibility. Moscow was unconvinced. “We know whose hands were used to commit this atrocity against Russia and its people. We want to know who ordered it,” President Putin said in a meeting with Russian security services on March 25. On March 26, chief of Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB) Alexander Bortnikov told the media that the US, UK, and Ukraine “are behind the terrorist attack.” Both Ukraine and the US quickly denied any involvement in the attack. Whatever the case, the terror attack cast a long shadow over the Ukraine conflict, including China’s effort to mediate between the warring parties for a possible end of the conflict. President Xi sent his condolence message to Putin on March 23, just five days after his message to the Russian president for his reelection.

China’s “Goldilocks” for Russia’s Bear

The March 22 Moscow terror massacre apparently prompted Russian FM Lavrov’s April 8-9 visit to Beijing for talks with both FM Wang Yi and President Xi. In “extensive talks” in Beijing, Wang and Lavrov worked out specifics for Putin’s official visit to China in mid-May, the SCO summit in Astana in June, and the BRICS summit in Kazan in October. “Summit diplomacy,” according to Wang, provided “strategic guidance” for relations between the two powers.

While talks with Wang covered “a broad range of issues,” Lavrov seemed to push for “a new security structure in Eurasia” vis-à-vis the Euro-Atlantic mechanisms of the “collective West.” He also revealed in the joint press conference with Wang that China agreed “to begin a dialogue on this matter.” Wang’s remarks did not touch on the subject but said that the two sides should uphold a non-aligned principle and posture, which required careful maintenance. The Chinese-language readout recorded that as “a responsible major power” China would always make decisions independently based on the circumstances regarding specific issues. Nor did the Chinese side reciprocate Lavrov’s “potential initiatives for marking the 80th anniversary of Victory over German Nazism and Japanese militarism” in 2025.

Russia’s desire for stronger security coordination with China was understandable, given mounting stress in fighting a de facto two-front war after the March terror attack: a “Western civil war” 2.0 with the “collective West” and a “civilization clash” with Islamic extremism. Russia in the 21st century is simultaneously confronting both whether or not there is any connection between the two-year Ukraine war and the Moscow terror attack on March 22.

Beijing understood Russia’s difficulties because China, too, was between a rock (Western hostility) and a hard place (Islamic extremism), albeit to a somewhat lesser degree. The steady rise of China since 1979, nonetheless, was accomplished within the existing liberal international order. In the past 45 years, China has adapted itself to it while transforming itself into a profoundly conservative actor in the world and values stability, predictability, and economic development perhaps more than any other major power. “In constructing a world order, evolution, peace, reform, and dialogue are better than revolution, violence, de-link, and confrontation,” said Prof. Zhao Huasheng, one of the most prominent Russologists in China in early March. A separate Eurasian security arrangement with Russia with the sole purpose of confronting the Euro-Atlantic system may not serve China’s interests for an inclusive global “community with a shared future for humanity.”

In the short term (May 5-10), Xi was scheduled to travel to France, Serbia, and Hungary, and would have a joint meeting with Macron and President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen. The goal was to promote a “sustained, steady, and sound development of China-Europe relations.

Chinese President Xi Jinping apparently joined the top diplomats’ talks at a certain point (right photo below), which was quite unusual. Xi stressed that China supported the Russian people in following a development path that suited their national conditions, and supported Russia in combating terrorism and maintaining security and stability. In the area of foreign policy coordinations, Xi stated that the two countries should work together in uniting countries in the Global South in building a community with a shared future for humanity.

Figure 4 Chinese President Xi Jinping meets with Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, April 9, 2024. Photo: Xinhua

Figure 4 Chinese President Xi Jinping meets with Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, April 9, 2024. Photo: Xinhua

Xi’s emphasis on the Global South did not necessarily mean that Beijing ignored Moscow’s security interests. In the first two years of the war, most southern and eastern countries including China chose to be neutual while favoring an early end of the conflict. Xi seemed to suggest to Lavrov, albeit indirectly, that Russia needed to more effectively engage the bigger and more dynamic world beyond the West, given the stalemate of the Ukraine conflict.

In his phone talks in early January 2024 with Lavrov, Wang Yi stressed that as two responsible major countries, China and Russia should strengthen strategic communication, build more strategic consensuses, and carry out more strategic cooperation on the future of mankind and the world as the means for “intensifying China-Russia strategic coordination (underlining added by author).” Wang did not specify the definition of “strategic.” The phrase, however, contrasts with concepts such as “short-term,” “secondary,” “immediate,” “transient,” etc.

More recently, Prof. Zhao Huasheng of Fudan University argued more explicitly that strategic opportunities needed to be taken whenever they appeared. Short-term benefits, however, should not be obtained at the expense of the long-term, holistic, and strategic interests. It was extremely important to avoid sharp turns and roller-coasting in bilateral relations particularly in times of radical changes in the world. Zhao’s remarks were made in March at the annual “2024 Russian-Chinese Dialogue” cosponsored by Fudan University in Shanghai and the Russian International Affairs Council led by Andrey Kortunov, director of the Russian International Affairs Council. At the end, Zhao went as far as to suggest that a stable and more resilient relationship between two large powers such as China and Russia required some “free space” between them.

“Friendship between gentlemen is as light as water (君子之交淡如水),” said China’s most respected ancient philaospher Zhuan Zi (庄子, 369-286 BC). A normal relationship in abnormal times, similar to the timeless “Goldilocks” choice for the middle position, may be the essence of the current Sino-Russian strategic partnership. The stage, however, was set for more dynamic interactions between Beijing and Moscow in the months ahead.

Jan. 2, 2024: China’s Vice Foreign Minister Sun Weidong meets Russian Ambassador to China Igor Morgulov in Beijing. They discuss issues the celebration of the 75th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations and the Years of Culture between China and Russia (2014-15). The two sides also exchange views on issues of mutual interest and concern.

Jan. 10, 2024: Chinese FM Wang Yi and Russian counterpart Lavrov have a phone conversation initiated by the Russian side. They discuss the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, BRICS issues, etc. Wang reportedly says that “China firmly believes that Russia will be able to successfully complete its important domestic political agenda, and maintain national stability and development.”

Jan. 13, 2024: Russian Foreign Ministry Spokeswoman Maria Zakharova says Russia regards Taiwan as an integral part of China, a reiteration of Russia’s “principled position” on the issue. Russia’s pronouncement comes immediately after Taiwan’s presidential election. China’s foreign ministry spokeswoman Mao Ning expressed appreciation for Russia’s remarks on Jan. 15.

Jan. 18, 2024: FM Lavrov says in a news conference on Russia’s foreign policy performance in 2023 that relations with China “are stronger, more reliable and superior to the military alliance of the Cold War era.”

Jan. 29, 2024: China’s Vice FM Sun Weidong meets in Beijing with Ambassador of Ukraine to China Pavlo Riabikin at the latter’s request. Riabikin invites Chinese President Xi Jinping to participate in the upcoming Global Peace Summit in Switzerland aimed at building support for the Ukrainian peace formula presented by Ukraine President Zelenskyy in November 2022. A press release by the Chinese Foreign Minister does not mention the invitation.

Jan. 29-30, 2024: Chinese Executive Vice FM Ma Zhaoxu visits Russia to hold consultations with Russian counterparts First Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs Vladimir Gennadievich Titov and Deputy Foreign Minister Ryabkov Sergey Alexeevich. They have “an in-depth exchange of views” on strategic stability, BRICS cooperation, and international and regional hotspot issues. Russian FM Lavrov meets Ma on Jan. 30. Ma also joins the first session of the BRICS in Moscow.

Feb. 6, 2024: Russian President Vladimir Putin gives an interview to US journalist Tucker Carlson. Putin dismisses the view that China threatens other BRICS members, points out the importance of cooperating with a country that Russia shares a long border, and emphasizes that China’s economy is already the largest in the world in PPP terms.

Feb. 8, 2024: President Putin has “an extensive telephone conversation” with Xi Jinping two days before Chinese New Year (Feb. 10). Their talks cover bilateral, regional, and global issues.

Feb. 9, 2024: Downtown Moscow kicks off a 10-day Chinese New Year celebration featuring more than 300 separate events/shows. This “first broad celebration” of the Chinese New Year in the Russian capital city is the first of a series of events as part of the Years of Culture of Russia and China in 2024-25. It also marks the 75th anniversary of diplomatic ties.

Feb. 16-17, 2024: Liu Jianchao, head of the CCP’s Liason Department, travels to Moscow for the first “For the Freedom of Nations” International Forum of Supporters of the Struggle Against Modern Practices of Neocolonialism. The forum is launched by the “United Russia” party chaired by Dmitry Medvedev, who meets Liu on the sidelines of the forum. More than 400 participants from over 55 countries join. Russian FM Lavrov also speaks at the forum.

Feb. 17, 2024: Chinese FM Wang Yi delivers a keynote speech at the annual Munich Security Conference (MSC). He reiterates China’s commitment to promoting peace talks for the Ukraine crisis. He also urges that nuclear wars must not be fought. Wang also maintains that Sino-Russian relations contribute to strategic stability in the world. In Munich, Wang also meets with Ukraine FM Kuleba on the sidelines of the MSC.

Feb. 28, 2024: Vice FM Sun Weidong holds consultations in Moscow with Russian Deputy FM Rudenko Andrey Yurevich on China-Russia relations, the SCO and Asia-Pacific affairs. Sun meets with Russian FM Lavrov.

March 2-8, 2024: China’s Special Representative on Eurasian Affairs Li Hui travels to Russia, Poland, Ukraine, Germany, and France for his second round of talks on the peaceful settlement of the Ukraine conflict. He holds talks with Russian Deputy FM Mikhail Galuzin on March 2 and meets FM Lavrov the following day. Li travels to Kyiv by train on March 7 and left in the evening after talks with Ukrainian Head of the Office of the President of Ukraine Yermak Andriy Borysovych, First Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Economy Yulia Svyrydenko and Minister of Foreign Affairs Dmytro Kuleba.

March 17, 2024: President Putin officially wins his fifth presidential term with 87.28% of the vote. Chinese envoy Li Hui leads a Chinese observer delegation to Russia on March 15-18. Putin is to be sworn in May 7. President Xi Jinping congratulates Putin on reelection on March 18. Xi says China stands ready to maintain close communication with Russia to promote the sustained, sound, stable, and in-depth development of a China-Russia comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination for a new era to benefit the two nations and their people.

March 22, 2024: Unidentified gunmen conduct a terrorist attack in Crocus City Hall in Krasnogorsk in the Moscow Region, killing 143 people and wounding more than 80. Xi Jinping extended condolences to Putin on March 23. Xi says that China opposes all forms of terrorism, strongly condemns terrorist attacks, and firmly supports the Russian government’s efforts to maintain national security and stability.

March 25, 2024: Chairman of China’s National People’s Congress (NPC) Zhao Leji meets with Deputy Chairman of the Russian State Duma Alexander Babakov in Beijing.

March 28, 2024: FM Lavrov says that China’s 12-point peace proposal should be a basis for negotiations because it means equal security to all participants in this process. Meanwhile, negotiations cannot be based on the “peace formula” proposed by Ukrainian President Zelensky and promoted by Europe and the United States.

March 29, 2024: China’s top legislator Zhao Leji meets Russian Deputy Prime Minister Alexey Overchuk in Boao where Overchuk attends the Boao Forum for Asia Annual Conference 2024.

April 3, 2024: China’s Assistant Foreign Minister Miao Deyu holds consultations with Russian Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Vershinin Sergey Vasilievich in Beijing on the UN affairs.

April 8-9, 2024: FM Lavrov visits Beijing for talks with Chinese counterpart Wang Yi. They discussed global, regional and bilateral affairs, as well as the Ukraine war issue. Lavrov also meets with President Xi.

April 16-18, 2024: China Coast Guard (CCG) sends a working group to Vladivostok to participate in China-Russia Coast Guard working-level talks. This is the first working-level talks between the two agencies after signing the memorandum of understanding last year.

April 16-18, 2024: Chen Wenqing, head of the Commission for Political and Legal Affairs of the CCP Central Committee, travels to Russia to attend the 12th International Meeting of High Representatives for Security Issues and visit Russia at the host’s.

April 17, 2024: China’s Minister of Education Huai Jinpeng visits Russia for the China-Russian University Forum and the SCO annual session of education ministers in Moscow. Huai presides over agreements signing ceremony between Moscow State University and seven Chinese leading universities.

April 24-26, 2024: China’s Defense Minister Dong Jun attends the SCO Defense Ministerial meeting in Astana, Kazahkstan. He also pays an official visit to Kazakstan.