Articles

Incorporating major foreign policy initiatives of leader Xi Jinping, Beijing completed its effort from the past two years with instructions in January on China’s new approach to foreign affairs to Chinese foreign policy officials and others concerned. The new approach added authority and momentum to Beijing’s emphasis since Xi’s summit with US President Joe Biden last November on greater Chinese moderation and restraint as a “responsible” great power pursuing peace and development in dealing with Southeast Asian neighbors and elsewhere. Nevertheless, Beijing remains selective in how it applies moderation, and the record of the past two years shows great swings between moderation and truculence in its approach to foreign affairs, depending on circumstances which remain subject to change. The success of China’s regional importance showed in Singapore’s Institute of Southeast Asian Studies annual survey of regional elites with China viewed as both the leading economic and political-security power, overshadowing the United States, and the judgment that if forced to choose between them, more respondents would select China than the United States.

Caveats to these positives for China include continuing strong regional concerns over China’s ambitions in Southeast Asia and the fact that the survey came during the height of the war in Gaza by Israel, which is supported by the US and viewed very negatively in the region. Meanwhile, the defiance of the Philippines, with strong military and political support from the United States, Japan, Australia, India, and other allies and partners, against coercive measures in the disputed South China Sea represented a major test of China’s avowed “restraint” in dealing with foreign differences.

Background: China’s New Moderate Approach to Foreign Affairs

The process of China’s new definition and clarification of its broader approach to foreign affairs developed over several years, culminating in authoritative instructions in January 2024 to Chinese party-state practitioners, propagandists, and related representatives to give top attention to the guidance of Xi Jinping Thought and to Xi’s personal leadership. Highlights of the new direction were Xi’s Global Development Initiative announced in 2021, his Global Security Initiative of 2022, and his Global Civilization Initiative of 2023.

For much of this time, Chinese rhetoric and practice became increasingly harsh against growing challenges it faced, notably from the Biden administration and the broadening and deepening alignment of allies and partners. Particular negative Chinese attention focused on the Biden government’s successful efforts with allies and partners in Asia and the Pacific, Europe, and North America to build domestic resiliency and international positions of strength. Chinese criticism reached a high point in October 2022, with Xi’s rhetoric at the 20th Chinese Communist Party Congress validating his ever-stronger dominance of leadership decision-making and repeatedly invoking the need to prepare for long-term struggle against foreign foes[RY1] [RY2] .

Nonetheless, to the surprise of many, Xi shifted to a notably more moderate approach to the United States and many of its allies and partners when meeting Biden at the G20 summit in Indonesia in November 2022. The process was derailed by acrimony over the discovery of Chinese spy balloons crossing US territory in February 2023, with harsh Chinese rhetoric and practices against the US and its allies and partners in Southeast Asia and elsewhere.

An initial authoritative foreign policy statement integrating Xi’s Development and Security Initiatives together with his Civilization Initiative announced in March 2023 and with his longer standing Belt and Road Initiative showed first in the keynote speech by Prime Minister Li Qiang at the Boao Forum for Asia on April 2023. He sharply contrasted China’s avowed plans for global governance with disruptive and confrontational actions of the United States and its allies and partners. There followed a State Council White Paper on Sept. 26 showing Xi’s “vision” of a new China-supported world order. The vision incorporated Xi’s contributions in his Development, Security and Civilization initiatives to lay out alternative global governance in contrast with the purported disruptive and confrontational actions of the United States and its allies and partners in the existing international order. A Foreign Ministry White Paper in October dealing with Chinese foreign policy in Asia made clearer for Asian governments the choice Beijing expected from them to make regarding alternative China-backed versus US-backed world orders.

Presumably for many of the same reasons as in November 2022, Xi again moderated in late 2023. Since then, Beijing in authoritative statements has tended to avoid harsh attacks on the US and its allies and partners seeking to support the existing world order. Notably Xi’s speech to the APEC leaders in California in November was uniquely positive and cooperative with all countries. He stressed that China remained committed to the path of peaceful development and did not intend to “unseat anyone.”

The Foreign Ministry Statement of Jan. 16, 2024 laid out the implications of the Central Work Conference on Foreign Affairs held mainly behind closed doors in December 2023. It was broadly in line with the moderate approach seen since November. It favored multipolarity and opposed the hegemonism and power politics carried out by unnamed countries. But there was no specific reference to the United States, its allies and partners, or even Taiwan. It stressed that Beijing is not pressing governments to choose between siding with China against the US and the West. It avowed the importance of “fighting spirit” in foreign affairs but also emphasized China’s role as a “responsible” power.

Recent developments

Seeking regional support for its new foreign policy approach and Xi’s vague but seemingly goal of “building a community of shared future” between China and neighboring countries was a top priority for 2024. It featured in Xi’s New Year’s address. Beijing notably sought endorsements during meetings with top regional leaders and in various UN resolutions.

Politburo Member and Foreign Minister Wang Yi was emphatic at the 60th Munich Conference in February that China would remain a “staunch force for stability” in a turbulent world. It would serve as “a responsible major country” with consistent policies and principles supporting cooperation among major countries, dealing effectively with international hotspots issues, enhancing global governance, and advancing global growth.

Wang Yi repeated these themes at a press conference at the National People’s Congress in March. He stressed that China strove to promote stability in relations with the United States. There was little of the harsh criticism of the US and other perceived opponents seen in Foreign Minister Qin Gang’s press conference at the National Peoples Congress in March of the previous year. Wang sought “common progress” with China’s neighbors which involved respecting each other’s core interests and concerns, seeking mutual benefit, and commitment to openness and inclusiveness in regional groupings.

Figure 1 Member of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee and Foreign Minister Wang Yi answered questions from Chinese and foreign media about China’s foreign policy and external relations on March 7, 2024. Photo: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China

Wang offered a benign view in a detailed response to a question about ASEAN and the Code of Conduct in the South China Sea, arguing that despite “turbulence” in the world, “peace and stability have been maintained” in the South China Sea by China and ASEAN countries. Without mentioning the Philippines or other South China Sea disputants or the United States and other powers concerned with Chinese expansionism at others’ expense, Wang advised that China employed “a high degree of restraint” in seeking to deal with differences. But he added that abusing China’s “good faith” and “distorting” maritime laws were unacceptable, and China would take “justified actions” and “prompt and legitimate countermeasures” against deliberate infringements and unwarranted provocations. He urged unnamed “certain countries outside the region” to not stir up troubles and problems in the South China Sea. He reiterated China’s commitment to the Declaration of the Conduct of the Parties in the South China Sea and highlighted China’s efforts to accelerate China-ASEAN negotiations on the Code of Conduct in the South China Sea.

Wang’s emphasis on “common progress” with China’s neighbors featured during his trips to Indonesia, Cambodia, and Papua New Guinea in April, with Chinese outlets highlighting Beijing’s economic and other benefits for the region while noting in measured language continued Chinese opposition to US policies. Notably, China Daily, commenting on April 26 on Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s visit, said Beijing was dissatisfied with Biden administration actions offensive to China concerning Southeast Asia and elsewhere. It pointed to the largest US military drill with the Philippines “in decades” and the deployment of advanced US mid-range missiles in the northern Philippines capable of hitting targets near Taiwan and “the whole southeast coastal region of the Chinese mainland.”

Rising Tensions in Philippines-China Impasse over Disputed South China Sea

By far the most prominent dynamic in China-Southeast Asia relations in 2024 has been rising friction resulting from Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos, Jr., backed strongly by the United States, Japan, Australia, India, South Korea, the European Union and NATO countries, continuing to challenge and defy China’s coercive activities in support of its claims to Philippine occupied and claimed territory in the South China Sea. The pattern of repeated Philippine challenges to China’s coercive measures and expansionist claims was set last year. The worsening of the impasse represents the most serious challenge to China’s emphasis on creating an international image of China as a stable and “responsible” major power employing “restraint” in dealing with Chinese disagreements with other countries.

Beijing has been placed on the defensive as the Marcos government no longer follows the practice, from before he took power in 2022, when the Philippines conformed with other South China Sea claimants and tended to avoid publicity as they faced unpublicized Chinese coercive measures, often carried out by the world’s largest fleets of modern Coast Guard vessels and Maritime Militia. Accompanying journalists now routinely provide and widely publicize high-quality video of the forceful measures including widespread use of water cannons, dangerous ship maneuvers, and occasional ramming, carried out by these much larger and more numerous Chinese vessels, depicting Beijing as a bully determined to have its way at others’ expense. The United States and other supporters use such evidence in justifying stronger support for the Philippines.

As seen in Wang Yi’s avoiding mention of the Philippines, the United States, or others by name when discussing South China Sea disputes at the National People’s Congress in March, high-level official Chinese discourse has tended to eschew harsh rhetoric while defending Chinese actions and claims and warning of negative consequence for the Philippines. Chinese foreign ministry and defense ministry spokesperson statements have taken pains to present justifications for China’s coercive measures as reflecting forbearance and restraint. As discussed below, official media have been selective in using more critical language in commenting on the Philippines and its international backers. President Marcos and his spokespersons, along with Japan and NATO have been criticized more strongly than the United States, which has been criticized more strongly than other backers of the Philippines, notably Australia.

Significant developments

On Jan. 30, CSIS Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative reported that Chinese Coast Guard and Maritime Militia blocking Philippine resupply missions to disputed Second Thomas Shoal had increased in frequency and intensity since 2022. However, throughout the reporting period, after confrontations between the PRC and Philippines Beijing attempted to seize the high ground by claiming that agreements between the two sides had been in place, that it was Manila that had been acting contrary to them, and that outside actors—and Manila’s collaboration with them, were the source of the tensions. The Philippines countered with continued publicity of incidents, and accounts from the Philippines, including from Marcos’ more China-friendly predecessor, did not lend credence to their contentions of a previous agreement.

On Jan. 5, the Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson condemned the second US-Philippines patrol in the disputed South China Sea (the first was held in November.) Nearly a week later, official media publicized a Chinese intelligence analyst claiming that the Marcos government’s confrontation with China over the Philippine outpost on a long grounded warship on Second Thomas Shoal was motivated by the possible collapse of the ship, domestic Philippine politics involving a dispute between Marcos and previous President Rodrigo Duterte, and US intensifying efforts “to contain” China. On Jan. 12, Chinese Coast Guard ships were videotaped by the Philippines as they drove away Philippine fishing boats near disputed Scarborough Shoal.

Diplomacy between the sides continued throughout the period. On Jan. 17, the eighth meeting of the China-Philippines Bilateral Consultation Mechanism on the South China Sea took place in Shanghai. Two days later, Beijing highlighted alleged agreement at the Shanghai meeting to “efficiently manage maritime emergences,” especially the situation at Second Thomas Shoal. On Jan. 23, reacting to sharp Chinese criticism of Marcos’ message congratulating the newly elected Taiwan president, Marcos reaffirmed his government’s one-China policy. On Jan. 25 the Chinese defense ministry spokesperson said Beijing was hopeful that the meeting in Shanghai on Jan. 17 would lead to resolving disputes through dialogues and consultations. However, he harshly criticized NATO’s increasing involvement in Asian security matters and Japan but not Australia in discussing Japan-Australia alleged joint efforts targeting China. This would prove to be a theme during the first four months of the year.

Figure 2 Chinese coastguard vessels fire water cannons towards a Philippine resupply vessel Unaizah May 4 on its way to a resupply mission at Second Thomas Shoal in the South China Sea, March 5, 2024 Photo: Adrian Portugal/Reuters

On March 5 a major incident took place involving Chinese Coast Guard ships using water cannons to block access to Second Thomas Shoal by two Philippine supply ships and two accompanying coast guard vessels; the incident was filmed by CNN and broadcast widely. China followed with proposals to avoid recurrence of such incidents which Beijing said the Philippines rejected. This was followed by another major incident involving Chinese Coast Guard ships blocking access to Second Thomas Shoal by a Philippines supply ship with construction materials and two accompanying Coast Guard vessels. Beijing accused the United States of instigating Manila’s provocations and warned the Philippines that relations with China were “at a cross roads.” China’s defense ministry spokesperson said on the 28th repeated provocations by the Philippines were the immediate cause of rising tensions in the South China Sea, while US interference was the biggest factor causing turbulence there. On March 26 China added India to the long list of countries it criticizes over South China Sea matters following the Indian foreign minister’s visit to Manila resulting in a joint statement critical of China on the South China Sea.

Figure 3 China’s top legislator Zhao Leji on Thursday delivered a keynote speech at the opening plenary of the Boao Forum for Asia Annual Conference 2024. Photo: Xinhua

On Feb. 5 China Daily criticized Marcos for reneging on the alleged agreement at the Jan. 17 meeting in Shanghai; it warned that China’s “considerable restraint” in dealing with Philippine “provocations” intruding in waters near Second Thomas Shoal and Scarborough Shoal could end, leading to “conflict.” On April 3 China’s foreign ministry spokesperson claimed the Marcos government had betrayed trust by not abiding by alleged Sino-Philippines agreements to tow away the ship grounded on Second Thomas Shoal in 1999 and to not build permanent facilities on the reef.

On April 11 China’s foreign ministry spokesperson said the Philippines had gone “back on its words” in refusing to remove the grounded warship on Second Thomas Shoal, by denying the existence of the “gentleman’s agreement” with China reached during the Duterte government and repeatedly infringing on China’s sovereignty, and abandoning the Marcos government’s “understanding” with China by sending construction material to reinforce the outpost on Second Thomas Shoal. However, former President Duterte subsequently denied there was such a gentleman’s agreement but he repeated his recollection of his first meeting with Xi at which the Chinese leader indicated that “China will go to war” to counter Philippine provocations. As of mid-April Chinese diplomats continued to claim the existence of a “gentleman’s agreement” to manage the situation at the Second Thomas Shoal, which it claimed the Philippines had abandoned.

Figure 4 Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte and President Xi Jinping of China at the Malacañang Palace in Manila on November 20, 2018. Photo: Malacañang

And as of April tensions had not diminished: On April 14 a Chinese Coast Guard ship blocked a Philippine maritime research vessel and an accompanying escort ship from entering waters claimed by China for eight hours, an incident not discussed by the two governments but reported by foreign media based on tracking data. China also stepped up criticism of Manila’s increasing cooperation with other powers, including when, on Feb. 19, a US B-52 bomber flew with three Philippine jet fighters as part of three days of joint air patrols over disputed territory in the South China Sea. China condemned the patrol, noting they were the first Philippine air patrols with a foreign country. In mid-March, after news reports of a summit in Washington on April 11 of the leaders of the Philippines, Japan, and the United States, official Chinese media begin repeatedly criticizing the leaders of the three countries for disrupting peace in the South China Sea. On April 7, the Philippines, the United States, Japan, and Australia began their first full-scale military exercise in the South China Sea. Chinese commentary took aim at the exercises a day later, though it focused criticism on Japan, with none against Australia.

The first batch of three batteries of the shore-based, anti-ship variant of the Indian BrahMos missile system arrived in the Philippines on April 19 despite low-level Chinese criticism of the agreement. The prominent negative Chinese reactions to the US-Japan-Philippine summit in Washington on April 11 included formal Chinese demarches to Japanese and Philippine ambassadors in China amid widespread attack on this “substantial new step in the US-led attempt to contain China.” Chinese commentary closed the reporting period by criticizing the large-scale annual US-Philippines Balikatan military exercises from April 22 to May 10 involving over 16,000 participants. It gave special attention to the US deployment of its new Typhon midrange ground-based missile launcher—capable of firing Tomahawk cruise missiles and SM-6 missiles—in northern Luzon, which Beijing saw as directly related to defending Taiwan.

Figure 5 President Joe Biden, center, Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., left, and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida pose before a trilateral meeting in the East Room of the White House in Washington, April 11, 2024. Photo: VOA News

Strengthening Ties between China and Indonesia

Indonesia’s President-elect Prabowo Subianto visited China and met President Xi on April 1. It was Prabowo’s first foreign trip since his election in February. As defense minister, Prabowo agreed to step up bilateral defense and security ties, working with China to ensure regional stability and to help fulfill Indonesia’s military hardware upgrade while boosting cooperation and dialogue in the defense industry. Prabowo also pledged to continue outgoing Indonesian President Jokowi’s “policy of friendship with China,” and promote the alignment of development strategies on the economy, trade, and poverty alleviation with China.

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi met Indonesian counterpart Retno Marsudi in Jakarta on April 18. Both ministers agreed on the urgency of implementation of a UN Security Council resolution for a ceasefire in Gaza, and discussed the prospects for resolving the Palestinian issue through a two-state solution. Wang was also in Indonesia to attend the “China-Indonesia High-Level Dialogue Cooperation Mechanism,” where senior ministers from both sides discuss cooperation in trade, business, and economic activities. China is Indonesia’s largest trading partner, with two-way trade volume reaching more than $127 billion. China is one of Indonesia’s largest foreign investors, with investment flows of more than $7.4 billion in 2023.

China Stages Live-Fire Exercises in Border Area with Myanmar

On April 2-3, the People’s Liberation Army Southern Theater Command’s ground and air forces engaged in live-fire exercises that included rapid deployments, precision strikes, and other operations near its border with Myanmar. The PLA explained that it is ready to “safeguard China’s sovereignty, border stability and the lives, properties and safety of the Chinese people,” referring to the rationale for the exercises in light of repeated clashes between Myanmar’s ethnic groups and the military junta. China helped broker negotiations that led to a truce in January between the Myanmar government and three ethnic groups, but fighting has continued. The agreement was supposed to see an immediate ceasefire, disengagement of military personnel, and peaceful negotiations to resolve the disputes. The military exercises were meant to press the parties involved to abide by the agreement. Deng Xijun, China’s special envoy for Asian affairs, visited Naypyitaw at the same time as the military exercises to discuss the latest developments in peace talks with Min Aung Hlaing, who leads Myanmar’s military junta.

China-Vietnam Relations Warming Up

Chinese Defense Minister Dong Jun and Vietnamese counterpart Phan Van Giang met in mid-April for the eighth border defense friendship exchange and announced the establishment of a hotline between the PLA’s Southern Theater Command and the Vietnamese navy. The hotline reflects both countries intention to make maritime cooperation a new highlight of cooperation despite competing claims in the South China Sea, and follows the agreement to set up a direct line between the countries’ defense ministries at the end of 2015.

In addition to stepping up defense ties, China and Vietnam are pressing ahead on cooperation on trade, business, and economic activities. Vietnam announced in April that it would begin construction of two high-speed railway lines further linking the two countries and facilitating trade. One railway line would run from Vietnam’s port cities of Haiphong and Quang Ninh through Hanoi to Lao Cai province, which borders China’s Yunnan province. The other would run from Hanoi to Lang Son province, which borders China’s Guangxi region, passing through an area densely populated with global manufacturing facilities, including some owned by Chinese firms. China remains Vietnam’s largest trading partner and a vital source of imports for its manufacturing sector. According to Vietnamese official data, two-way trade in the first quarter of this year rose 22% from a year earlier to $43.6 billion.

Cambodia: China-backed Canal; Warships at Naval Base

Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Manet on March 12 attacked critics of a proposed $1.7 billion China-funded Funan Techo Canal project which would bypass Vietnam, purportedly allow the Chinese navy access near the border with Vietnam, and reportedly drain fresh water from the Mekong River. The project will allow shipping from Phnom Penh to divert from the southern Mekong River controlled by Vietnam to a 180-km canal through Cambodian territory to the deep-sea port at Kep in southern Cambodia. The project reportedly will get underway this year and will be built and operated by a Chinese company. The cost will be paid by user-fees charged by the Chinese company, which will transfer ownership to Cambodia in “40-50 years.”

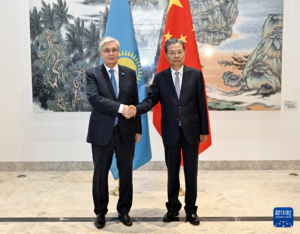

Figure 6 Zhao Leji, chairman of the National People’s Congress (NPC) Standing Committee, meets with Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, who is here to attend the Boao Forum for Asia Annual Conference 2024, in Boao, south China’s Hainan Province, March 28, 2024. Photo: Xinhua/Yin Bogu

China Daily on April 10 disclosed former Prime Minister Hun Sen and now president of the Supreme Privy Council and chairman of the Cambodian People’s Party strongly supported the canal and sought China’s backing in building the project in discussions with third-ranking Chinese leader Zhao Leji in a meeting in Beijing of March 28. The Cambodian leader went on to deny the presence of Chinese troops at the Ream Naval Base, located along the coast to the west and north of Kep, although the CSIS Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative reported April 18 that two Chinese Navy ships have spent the past four months with exclusive use of a new pier at the base built by China.

Outlook

China’s comparatively moderate foreign policy approach in Southeast Asia over the past six months will be challenged by active US-backed efforts to counter adverse Chinese practices. Though the rationale for continued Chinese moderation remains strong, the defiant Philippines—backed by the US—heads the list of reasons Beijing may adopt tougher measures.

Jan. 5, 2024: China’s foreign ministry spokesperson condemns second US-Philippines patrol in the disputed South China Sea.

Jan. 11, 2024: Official Chinese media publicizes an intelligence analyst’s claim that the Philippine government’s confrontation with China over the Philippine outpost on a long grounded warship on Second Thomas Shoal is motivated by the possible collapse of the ship, domestic Philippine politics involving a dispute between Marcos and former President Rodrigo Duterte, and intensifying US efforts “to contain” China.

Jan. 12, 2024: Chinese Coast Guard ships are videotaped by the Philippines driving away Philippine fishing boats near the disputed Scarborough Shoal.

Jan. 12, 2024: China brokers a truce and ceasefire agreement in Kunming between Myanmar’s military regime and an alliance of Myanmar’s ethnic minority groups. The agreement also includes the disengagement of military personnel and the settlement of their disputes through negotiations.

Jan. 17, 2024: China and the Philippines convene the 8th Bilateral Consultation Mechanism on the South China Sea in Shanghai. The two sides agree to manage maritime disputes through diplomacy and to maintain dialogue to avoid escalation.

Jan. 19, 2024: Beijing highlights an alleged agreement at the Shanghai meeting to “efficiently manage maritime emergencies,” especially at Second Thomas Shoal.

Jan. 23, 2024: Reacting to sharp Chinese criticism of a message congratulating the newly elected Taiwan president, President Marcos reaffirms his government’s one China policy.

Jan. 25, 2024: Chinese Defense Ministry spokesperson says Beijing is hopeful that the Jan. 17 meeting in Shanghai would lead to resolving disputes through dialogue and consultations.

Jan. 30, 2024: CSIS Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative reports that Chinese Coast Guard and Maritime Militia blocking Philippine resupply missions to disputed Second Thomas Shoal had increased in frequency and intensity since 2022.

Feb. 5, 2024: China Daily criticizes Marcos for reneging on the alleged Jan. 17 agreement; it warns that China’s “considerable restraint” in dealing with Philippine “provocations” in waters near Second Thomas Shoal and Scarborough Shoal could end, leading to “conflict.”

Feb. 19, 2024: A US B-52 bomber flies with three Philippine jet fighters as part of three days of joint air patrols over disputed territory in the South China Sea, prompting Chinese condemnation.

Feb. 23, 2024: Official Chinese media reports that a Philippine government vessel with news reporters on board was expelled from waters near Scarborough Shoal by Chinese Coast Guard ships.

March 1, 2024: China and Thailand implement a bilateral visa waiver agreement, enabling visitors from both countries to travel between China and Thailand without visa requirements. The measure is seen as a way to revive Thailand’s tourism industry as the new Thai government aims to attract more than 8 million Chinese visitors in 2024.

March 5, 2024: China and Thailand sign memorandums of understanding to cooperate on the peaceful use of outer space and international lunar research stations. The two countries will form a joint working group on space exploration and applications, enhancing data exchanges and personnel training.

March 5, 2024: Chinese Coast Guard vessels use water cannons to block and prevent Philippines’ supply ships and coast guard vessels’ access to Second Thomas Shoal, a major incident that prompted swift rebuke from the Philippines.

March 18, 2024: Chinese media begin criticizing the leaders of the US, Japan, and the Philippines in response to news of a trilateral summit between them in April, accusing the three governments of disrupting peace in the South China Sea.

March 22, 2024: China and Singapore announce that they will restart a high-level bilateral forum, the Social Governance Forum, in June. The forum will cover an in-depth exchange of views on cooperation in such areas as social governance, security and law enforcement, the building of rule of law, and managing interracial and religious diversity.

March 23, 2024: Another major incident takes place involving Chinese Coast Guard ships blocking access to Second Thomas Shoal by a Philippines supply ship with construction materials and two accompanying Coast Guard vessels. Beijing accuses the United States of instigating Manila’s provocations and warns that Manila’s relations with China were “at a cross roads.”

March 26, 2024: China adds India to the list of countries it criticizes over South China Sea matters following the Indian foreign minister’s visit to Manila resulting in a joint statement critical of China on the South China Sea.

March 28, 2024: China’s defense ministry spokesperson says repeated provocations by the Philippines were the immediate cause of rising tensions in the South China Sea, while US interference was the biggest factor causing turbulence there.

March 30, 2024: In the keynote speech at the annual Boao Forum for Asia, Chinese leader Zhao Leji ignores disputes over the South China Sea and stresses the positives in Chinese foreign policy.

April 1, 2024: Xi Jinping meets Indonesia’s President-elect Prabowo Subianto in Beijing. It is Prabowo’s first foreign trip since his election in February. Both leaders agree to deepen bilateral cooperation across all domains.

April 2, 2024: ASEAN and China reaffirm commitment to enhance their Comprehensive Security Partnership at the 25th anniversary of ASEAN-China Joint Cooperation Committee Meeting in Jakarta. Both sides agree to enhance cooperation through dialogue on nontraditional security, trade and investment, science and technology, public health, and the environment, among other issue areas.

April 3, 2024: China carries out live-fire exercises near its border with Myanmar as it presses the country’s military and armed ethnic groups to implement a January truce brokered by Beijing.

April 3, 2024: China’s foreign ministry spokesperson claims the Marcos government betrayed trust by not abiding by alleged Sino-Philippines agreements to tow away the ship grounded on Second Thomas Shoal in 1999 and to not build permanent facilities on the reef.

April 7, 2024: Philippines, the United States, Japan, and Australia began their first full-scale military exercise in the South China Sea. The following day Chinese commentary takes aim at the exercises, focusing criticism on Japan, and not on Australia.

April 9, 2024: Cambodian Senate President Hun Sen publicly denies reports and suggestions that a new navigation canal project through the country’s south would facilitate the entry of Chinese naval ships up the Mekong River. The 180-km Funan Techo canal will be built and operated by Chinese companies and will be operational by 2028.

April 11, 2024: China’s foreign ministry spokesperson says the Philippines “went back on its words” in refusing to remove the grounded warship on Second Thomas Shoal, in denying the existence of the “gentleman’s agreement” with China reached during the Duterte government by repeatedly infringing on China’s sovereignty, and abandoning the Marcos government’s “understanding” with China by sending construction material to reinforce the outpost on Second Thomas Shoal. Former President Duterte subsequently denies there was a gentleman’s agreement but repeated that at his first meeting with Xi the Chinese leader indicated that “China will go to war” to counter Philippine provocations.

April 13, 2024: China and Laos celebrate the first anniversary of the launch of cross-border passenger railway services linking Kunming in China’s Yunnan province with the Laotian capital of Vientiane. A new railway service line between Xishuangbanna, Yunnan’s southernmost tip, and Luang Prabang in northern Laos, is announced to mark the anniversary. The bilateral railway project, under China’s Belt and Road Initiative, has boosted cross-border trade and tourism.

April 14, 2024: Chinese Coast Guard ship blocks a Philippine maritime research vessel and an accompanying escort ship from entering waters claimed by China for eight hours, an incident not discussed by the two governments but reported by foreign media based on tracking data.

April 15, 2024: Negative Chinese reactions to the US-Japan-Philippine summit in Washington on April 11 include formal Chinese demarches to Japanese and Philippine ambassadors in China attacking the “substantial new step in the US-led attempt to contain China.”

April 16, 2024: China and Vietnam announce the establishment of a new hotline between the PLA’s Southern Theater Command and the Vietnamese navy to manage the risk of conflict and improve lines of communication between the two sides on maritime issues.

April 18, 2024: Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi visits Jakarta to meet with his Indonesian counterpart Retno Marsudi. They call for an immediate ceasefire in Gaza.

April 18, 2024: Chinese diplomats provide more detailed information supporting its claim about a “gentleman’s agreement” over Second Thomas Shoal.

April 19, 2024: First batch of three batteries of the shore-based, anti-ship variant of the Indian BrahMos missile system arrive in the Philippines against a background of low-level Chinese criticism of the agreement.

April 22, 2024: Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi visits Cambodia to meet senior Cambodian officials and discuss bilateral cooperation on security and economic ties.

April 22, 2024: Chinese commentary criticizes the large-scale annual US-Philippines Balikatan military exercises from April 22 to May 10 involving over 16,000 participants.

April 25, 2024: In response to China’s announcement of its annual fishing ban in the South China Sea from May to August, Vietnam’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs declares that the fishing ban violates Vietnam’s sovereignty over the Paracel Islands.

April 25, 2024: New satellite imagery from the Center for Strategic and International Studies shows that China’s naval vessels are operating and deployed permanently at Cambodia’s Ream Naval Base. The vessels are engaged in brief exercises at sea and have exclusive access to Ream.

April 26, 2024: Chinese Public Security Minister Wang Xiaohong meets Myanmar’s Home Affairs Minister, Lt. Gen. Yar Pyae, in Beijing. They discuss collaboration to crack down transborder crime, online syndicates, and scam centers operating along the two countries’ borders.

April 30, 2024: China’s coast guard expels a Philippine coast guard ship from waters adjacent to the contested Scarborough Shoal, prompting protests from senior officials in Manila.