Articles

In the first four months of 2020, as COVID-19 raged throughout the world, Russia and China increased, and even intensified, their diplomatic interactions, mutual support, and strategic coordination. The patience for maintaining an informal entente, rather than an alliance, seemed to be running thin. This happened even as the city of Moscow’s own brief “Chinese exclusion” policy evoked sharp dissonance in China’s public space. These developments occurred against the backdrop of a Middle East crisis and political shakeup in Russia. As the world beyond them sank into a state of despair, disconnect, and devastation, the two large powers moved visibly toward each other amid an increasing backlash from the US, particularly regarding China’s early actions in the pandemic.

Before COVID

The first signs of the disastrous pandemic in late 2019 got little attention outside China. At the beginning of the year, even Moscow and Beijing were more shocked by the US drone killing of Iranian Gen. Qasem Soleimani, commander of Iran’s Quds Force, on January 3.

Russia and China reacted quickly and strongly to the incident. In their telephone conversation the day after Soleimani’s assassination, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi called the killing “unacceptable,” “unlawful,” and “in violation of the UN Charter.” Despite the strong rhetoric, the two top diplomats called for de-escalating the crisis and taking joint steps to create conditions for the peaceful resolution of conflict. To achieve this, they talked about how to coordinate policies in the UN Security Council. On January 7, China and Russia blocked a UNSC statement on the December 31 attack on the US embassy in Iraq, insisting that any such statement by the UN Security Council should also include the latest developments (such as Soleimani’s killing, among other things).

China-Russia diplomatic moves reflected a deep concern over the escalation of the conflict between Iran and other regional players (Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the US), which seemed well-founded, considering Iran’s retaliatory missile attacks on two US military bases in Iraq on January 8, along with the accidental downing of Ukraine International Airlines Flight 752 flying out of Tehran to Kiev.

In the longer run, neither China and Russia would want to see the crisis escalate and further damage the already crippled Iran nuclear deal. The killing of all 176 passengers and crew of the Ukraine International Airlines flight, ironically, seemed to function as a calming factor, as the parties involved stepped back from the edge of war.

Viral Diplomacy: The China Phase

As Russia and China moved quickly to coordinate policies on the Middle East, Beijing watched from the sidelines, anxiously, as Putin reshuffled the government and revised the constitution to preserve the legacy of his first 20 years in power. At the end of April, however, the Kremlin politicking was suddenly disrupted when Russia’s new Prime Minister Mikhai Mishustin was infected by coronavirus. “Prime ministers in and out, but iron man Putin stays on,” commented Wu Yan (铁打的普京,流水的总理), a young Chinese scholar fluent in both Russian and English.

But the most important factor for the China-Russia strategic partnership was probably the rapid unfolding of the coronavirus pandemic. From late December the Chinese government was in overdrive in dealing with the rapid spread of the deadly virus. This included China’s first report to the World Health Organization (WHO), neighboring countries, and the US on January 3, the first publication of the genetic sequence of the coronavirus at Virological.org on January 11, and the lockdown of Wuhan on January 23.

On January 31, Putin sent a message to Chinese President Xi Jinping to express his deep sympathy and support for those affected by the virus. He also confirmed Russia’s readiness to provide the necessary assistance to China “as soon as possible.” The next day, Lavrov talked to his Chinese counterpart Wang by phone, and spoke highly of measures taken by China in fighting the coronavirus. This was followed by the announcement on February 4 that Russia would provide humanitarian aid to China for combating the COVID-19 outbreak. On February 5, the first shipment of Russian medical equipment arrived in Wuhan. On the same day, five Russian pandemic experts arrived in Beijing and were received by Deputy Foreign Minister Le Yucheng. They were “the first, and so far only,” group of foreign experts coming to China during the pandemic, according to the Chinese foreign ministry. On the same day, while receiving letters of credence from 23 newly-appointed foreign ambassadors, Putin told China’s new ambassador Zhang Hanhui that relations with China were “at an unprecedentedly high level,” “ties in the field of defense and military-technical cooperation are developing successfully,” and Russia was “ready to render help and every kind of assistance to the friendly Chinese people.” On February 9, the Russian Ministry of Emergency Situations delivered 23 tons of medical supplies to Wuhan, including 2 million masks.

Russia’s support came at a time when both the infection and death rates in China were climbing at an alarming rate. It was also a time when China was struggling with the West/US in the public space. US Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross’ statement on January 30 that the pandemic would “help to accelerate” the return of jobs to the US and The Wall Street Journal’s provocative headline on February 3, declaring China the “sick man of Asia,” were shocking to Beijing.

In contrast, messages from Russia to China were largely sympathetic, positive, and supportive. In addition to Putin’s swift and strong support to China, the official Russian Newspaper ran an editorial on February 10 titled “Friend In Need” and an entire page with huge Chinese characters spelling out “Wuhan, China, hold on! We are together!”

Figure 1 Russian Newspaper ran an entire page in support of Wuhan, China. Photo: Huanqiu

Russia impressed the Chinese with its foreign ministry spokesperson Maria Zakharova, who has an extensive background in China and who used the Chinese language in her daily press briefing on February 10 to convey Russia’s support:

We really want China and the Chinese people to act as one and unite in countering the epidemic to protect China as the ancient towers of the Great Wall do. Russia feels for the people of China during these difficult times. We are fully behind them and we would like to sincerely wish them every success in overcoming this epidemic.

In addition to using her Chinese fluency, which is unique in Russia’s and other foreign ministries around the world, Zakharova produced perhaps the strongest words against what she saw as the unwarranted criticism of China in the Western media:

… reading the foreign press, monitoring reports from Western news agencies and watching television, I am shocked that all this appears in states that not only consider themselves civilized but who also preach the lofty ideals of democracy and upholding human rights at international venues. … They are using disinformation and fraudulent facts, and are showing a lack of respect and sympathy which is so badly needed by the country and people that have been hit with the unprecedented spread of a new virus. At the end of the day, they should come to their senses, gather their wits and recall or probably read again everything that was signed and everything that was declared by the UN and its agencies. … If a country and its people are fighting such a dangerous and challenging epidemic, it is possible and necessary to display sympathy.

Russia also used its dual chairmanship of both BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) for 2020 to galvanize multilateral support for China. On February 11, Russia issued a BRICS chairman’s statement on behalf of other members of the group supporting China’s effort against coronavirus pandemic. “The BRICS countries commit to work together in a spirit of responsibility, solidarity and cooperation to bring this outbreak under control as fast as possible. They underline the importance of avoiding discrimination, stigma and overreaction while responding to the outbreak,” said the statement. Three days later, the SCO issued a statement on the coronavirus epidemic, reaffirming its “readiness to render China the necessary assistance and to closely cooperate in the spirit of the 10 June 2018 Declaration on Joint Countering of the Threats of Epidemics in the SCO Space.”

Moscow’s “Hunt” for Chinese

The coronavirus outbreak in China in early 2020 led to frequent high-level contacts between top Russian and Chinese officials and diplomats. The Russian government also took early and swift actions to prevent and contain the spread of virus from China. However, their handling of potential outbreaks, and of Chinese people suspected of spreading the virus, led to tensions very much at odds with the two nations’ cooperation in international diplomacy.

On January 31, Russia’s Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin, appointed to the position just two weeks earlier, took several decisive actions, including extending the temporary closure of five port entrances in Russia’s Far Eastern regions bordering China, which had been closed on January 24 for the Chinese New Year. He also decided to radically reduce air travel to and from China, evacuate Russian citizens, and prepare to provide medical and humanitarian aids to China. The Mishustin government was also drafting a temporary ban on working visas for Chinese citizens.

On February 1, Putin authorized Russian Aerospace Forces to evacuate Russian citizens from “areas of the People’s Republic of China most affected by the coronavirus.” Four days later, Russian planes evacuated several hundreds of Russian and CIS country citizens from Wuhan. More than 10,000 Russians, including 6,000 students, chose to stay in China through the pandemic because they believed that China would be able to beat back the virus, according to Chinese and Russian sources.

Russia’s actions came in the wake of US evacuation of US citizens and diplomats from Wuhan on January 25 and travel restrictions to and from China on January 31.

These early actions by the Russian government, though necessary and understandable given the quick spread of the virus and the lack of any effective treatment, were disruptive for many on both sides. For example, price for fresh produce in Russian Far Eastern regions shot up 40-50% as a result of the extended border closing. Russian local governments would have to ease the ban in early February.

China’s vibrant social media, too, was saturated with complaints and even anger at Russia’s actions, particularly the perceived harsh measures taken by the new prime minister. A triggering event was the press briefing by Mishustin on February 3 when he used the word “repatriation” in response to a question about possible government actions for coronavirus. His response was that the coronavirus was defined as a “first-level danger,” meaning the government could expel, monitor, and detain infected foreigners.

Mishustin’s response was said to be a standard operational procedure for the Russian government to any “first-level danger” based on previous governmental directives. The Russian Ministry of Health and Chinese embassy in Russia clarified the “misinterpretation” of the policy in early February that the infected people would be treated first in Russia. In late February, however, China’s social media exploded after Moscow municipal authorities took sweeping and discriminative actions to detain, prosecute, and possibly repatriate 80 Chinese citizens for allegedly violating Russia’s 14-day self-isolation rule. Many of them were said to be handled roughly by local authorities with little prior information and proper procedures. This happened in the wake of the alleged actions in Moscow, starting from February 19, to identify, question, and register only Chinese people in public transit systems and by taxi drivers.

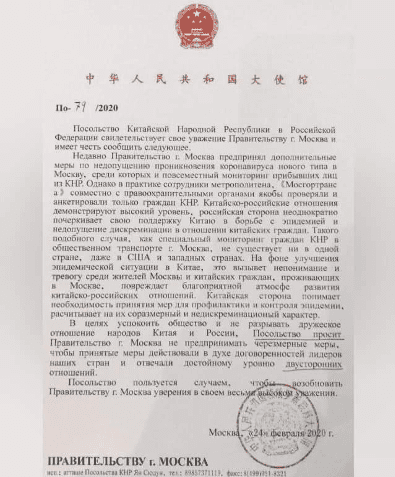

The hunt for Chinese in Moscow was so disturbing that the Chinese embassy in Moscow reportedly issued an inquiry on February 24 with the Moscow municipal authority asking for “appropriate, non-discriminatory, and non-excessive policies” toward Chinese citizens in Moscow, according to liberal Russian media. They went as far as to produce an original copy of the Chinese embassy statement to the Moscow municipal government on February 24 with a quite unusual statement that “Chinese citizens are not specially monitored in such a way by any government in the world, including those of the US and other Western nations.” Such strong, and certainly undiplomatic, wording is rare in the Chinese Foreign Service, let alone to a strategic partner such as Russia.

Figure 2 The Chinese embassy in Moscow reportedly requested non-discriminatory policies toward Chinese citizens in Moscow. Source: Toutiao

Press Secretary of the Russian President Dmitry Peskov denied on February 26 that Chinese citizens were targeted and discriminated in Moscow. Moscow Mayor Sergey Sobyanin also denied the allegation the following day. Russian media, however, showed that the Moscow transit authorities apparently informed its employees previously via internal email that bus and train conductors would inform police if Chinese were on board. This email instruction was said to be based on the Russian government’s decision to ban Chinese citizens from entering Russia starting from February 20.

Chinese diplomats worked with the Moscow government to offer clarity while reaching out to the detainees with food, psychological assistance, and legal advice. On March 1, the embassy dismissed alleged violent enforcement of the law by Russian police and that only Chinese citizens were detained. China’s mainstream media also warned about fake news and rumors at work to weaken China-Russia strategic partnership. It happened that liberal, or pro-West, media in Russia were most active in reporting the event.

The legal procedure to repatriate Chinese detainees continued in early March, including a statement by Deputy Mayor of Moscow Anastasia Rakova that Chinese detainees would be deported. After the first round of legal procedures, Chinese detainees were informed that they would be fined 5,000-10,000 rubles and then expelled with a five-year ban for traveling to Russia. In contrast, Russian detainees were fined only 1,000 rubles and a 14-day quarantine. On March 7, the first repatriations of four Chinese citizens were implemented.

Russia’s legal practices shocked Chinese, including some opinion leaders and academia. Hu Xijin, editor of Global Times in Beijing, explained on March 2 the impasse with a multi-dimension interpretation of Russian perceptions of China. First, there is no question that the Russian government considers relations with China highly imperative and Russian society also supports such a policy. Societal relations, however, were not as positive as those at the official level. Second, the steady rise of China had led to a complex mentality of admiration, disbelief, envy, and even enmity. Increased interactions between Russians and Chinese, too, create friction as a result of the dishonest behavior of some Chinese venders in Russia, which provides corrupt police with an excuse to manipulate cases involving Chinese. Finally, both sides have those who do not want to see high level bilateral tires presumably at the expense of respective relations with the West/US.

On March 9, Prof. Wu Dahui, a leading Russologist in Beijing’s Qinghua University, pointed out serious flaws in Russia’s handling of the case, and hoped that Russia would be gentler and more professional in how it treated detainees. Wu reminded readers not to forget the selfless help the Russians provided to China at the onset of the pandemic. As a true friend of Russia, however, China should also point out problems and disharmonies from both sides for long-term stability and development of the Sino-Russian strategic partnership.

On March 23, a Russian appeals court dismissed the first court ruling to repatriate a senior student in Moscow State University, leading to dismissing deportation verdicts for most of the cases, according to Chinese sources.

Moscow’s obsession with Eastern sources of the virus was understandable, given the still high infection rate in China in February. This, however, was apparently driven, and reinforced, by the widely spread misconception in Russia that coronavirus only infects Asians, particularly the Chinese. In a January 31 press briefing, Russian Deputy Prime Minister Tatyana Golikova was asked if the virus spread only among Chinese. She dismissed the claim.

For almost a month after Russia imposed travel bans to China, there was, at best, inadequate attention to Europe. Russia imposed “severe travel restrictions” on air travel with Europe only on March 13, one day before the US bans, when Italy had a total of 17,660 cases. In retrospect, most of Russian’s cases of infection originated from Europe from late March. On the same day, China’s daily infection cases were down to just 13.

Viral Diplomacy: Russia’s Turn

At the peak of China’s pandemic in early February, both Russia and China tried to make sure that high-level exchanges would continue despite the distortion of normal activities on the Chinese side. On February 10, Beijing confirmed Xi’s plan to attend the early May celebration of the Soviet victory over Nazi Germany. China’s decision was not easy given the daily infection rate of over 3,000 for February 9 and its peak three days later of 15,152. Preserving and promoting strong ties with Moscow, however, was paramount for Beijing.

For Russia, business-as-usual seemed assured in early February as its daily infection number was still in single digits. Russian Ambassador Andrey Denisov indicated that the pandemic would not affect relations with China. Denisov’s confidence was based on the normal pace of bilateral exchanges, which usually picks up from late March. Xi’s Moscow trip for the 75th anniversary of Word War II was part of five summits planned for 2020. Additionally, the Russian prime minister would visit China in the second half of the year. “2020 will continue the frequency of senior meetings at and above deputy ministerial level, of which there are almost 200,” said Denisov, “and they include meetings of foreign and defense ministers.”

For much of February and early March, Putin was preoccupied by constitutional revision, which would prolong Putin’s presidency beyond 2024, as well as imposing term limits for future Russian presidents. Putin’s seemingly contradictory efforts reflected both the potential and limits of his authority over a large number of liberal, or pro-West, Russian political elites. It also reflects a creeping anxiety about uncertainty in the post-Putin era. The Duma’s passing of the constitutional revision on March 10 resolved the dilemma, at least for the time being. Chinese foreign ministry spokesman Geng Shuang said that China hoped and believed that Russia would be able to maintain social stability and economic development. And China respected and supported, as it always did, Russia’s choice in selecting its own governance model.

On March 17, when there were only 21 cases, Putin confidently declared that Russia had managed to contain the “massive penetration and spread of the infection in Russia.” The confidence on both sides (China’s new infections had fallen considerably by mid-March) led to a surge of joint diplomatic activities. The next day, Lavrov and his Chinese counterpart Wang held a telephone conversation, focusing on the pandemic and the possible activities of the UN Security Council—now chaired by the PRC—and preparations for the summit of permanent members of the Security Council, a vision of Putin’s since January for the 75th anniversary of WWII ending. On March 25, Russia and China were part of the joint address (with Venezuela, Iran, North Korea, Cuba, Nicaragua, and Syria) to the UN secretary general, urging the withdrawal of unilateral sanctions during the spread of the coronavirus. At the G20 emergency summit on March 26, Putin also initiated the “green corridors” idea that would be free of trade wars and sanctions for the mutual supply of medicines, food, equipment, and technology. He suggested a collective moratorium on restrictions affecting basic necessities and financial transactions for purchasing them.

From late March, Russia’s infection rate started its steady climb (500 for March 31) and accelerated through April (with 7,099 cases on April 30 alone). The scope and speed of Russia’s increase of infection were alarming for both sides. This led to increased communication at the top level. Putin and Xi had “an in-depth discussion” over the phone on April 16. They discussed exchange of experts and medical equipment, medicines, and protective gear. Xi promised China’s strong support to Russia and hoped Russia would help Chinese citizens living in Russia. Putin said it was unacceptable to blame China as the source of the virus. Top diplomats also communicated frequently (Lavrov-Wang on March 27 and April 14, and their deputies on April 10, 22, and 24).

Part of their exchange was about land and air travel restrictions on Russia imposed by China starting from April 7 and then tightened on April 14. Meanwhile, there was a steady flow of Chinese PPE to Russia. The first plane load (26 tons) was delivered to Russia on April 2. On April 11, a group of Chinese medical experts arrived in Moscow, at which Chinese ambassador to Moscow Zhang Haihui declared that “today we are all Muscovites.” More Chinese aid was soon to follow, according to Chinese Ambassador to Russia Zhang Hanhui. Russian procurement of PPE from China was also accelerating. On April 20, “when our Chinese friends encountered difficulties in February, we sent 2 million masks to them,” remarked Putin, “We have now received 150 million masks from China,” he added. From April 6-28, 54 Aeroflot cargo planes brought back 205 million masks from China and many tons of other PPE, according to Aeroflot spokesperson Yulia Spivakova.

From Alignment to Alliance?

The reversal of fortunes for China and Russia in their dealings with the pandemic in the first months of 2020 led to more cooperation and coordination between the two Eurasian giants. It was the US factor, however, that gave extra impetus for Moscow and Beijing to coordinate policies more closely in the month of April.

The blame game between Washington and Beijing was already in full speed in March. April, however, witnessed heightened mutual accusations. On April 8, ABC reported that US military intelligence had warned the Trump administration about the pandemic as early as November 2019. Despite a quick dismissal by the US Defense Department, the ABC report shocked many in China because of the US ability to monitor, and even predict, a pandemic even a month before China confirmed its first few cases on December 27. Six days later, a Washington Post story again pointed the finger at China’s possible culpability for leaking the virus.

On April 14, Lavrov had a phone call with Wang. Lavrov thanked China for medical assistance and said that close cooperation in the pandemic indicated special and strategic significance of the bilateral ties. Russia also opposed politicizing the pandemic and criticized how “a few nations” tried to cast the blame on others. While defending the WHO, Lavrov also disputed the argument that China “will have to pay everyone for spreading this infection.” It was “beyond the pale,” said Lavrov, “to hear someone in London throw some numbers in the air and came up with 3.7 trillion dollars or euros that China allegedly owes to the EU for damages caused by the pandemic.”

The Trump administration launched on April 15 a coordinated effort accusing China of covering up its Wuhan lab leaks, a lack of transparency for six weeks, and a deliberate delay in reporting the pandemic. This was done with the Defense Department, Congress, and conservative media. Accusations that China had spread the virus around the world were much stronger than in mid-March, when Trump mostly performed a solo play by using phrases such as “Wuhan virus” or “Chinese virus” in his daily tweets and press briefings.

China and Russia reacted swiftly to the new US accusations. Xi and Putin spoke on the phone on April 16. In addition to praising China’s consistent and effective actions to stabilize the situation in China, Putin stressed that it was “counterproductive to accuse China of releasing information to the global community on this dangerous infection in an untimely manner.”

While fending off US accusations, Russia and China also went on the offensive by accusing the US of responsibility for the pandemic. On April 17, Chinese Ambassador to Russia Zhang Hanhui presented to the Russian media TASS findings that gene sequencing of the coronavirus indicated that the virus was imported to Wuhan, instead of emerging there.

On the same day Zakharova, the Russian foreign ministry spokesperson, questioned the purpose of US biochemical labs outside the US. “We cannot rule out that the Americans use such reference laboratories in third countries to develop and modify various pathogenic agents, including in military purposes,” she commented, with a special reference to a Georgia-based US biological laboratory. This was the second time that Zakharova made reference to the US labs in foreign lands in 2020. Her February 12 briefing provided more details.

For several years, the issue of US bio labs abroad was raised by Russian foreign and defense officials. Putin questioned it back to October 2017. Although Russian stories of US labs were discussed in Chinese social media and public space, China never officially endorsed the claim until April 29 when Chinese foreign ministry spokesman Geng Shuang backed the Russian position. “We took note of the statement made by the Russian foreign ministry spokeswoman [Zakharova]. The United States has created many laboratories in the territory of the former Soviet Union, which evokes serious public worries in the neighboring countries concerned,” Geng told a briefing. “The local public has been insistently demanding these facilities should be closed down. We do hope that the American side will display a responsible attitude, take into account the official concern of the world community and make real steps to eliminate such fears.” Geng’s phrase was quite reserved. The substance of his statement, however, indicated much closer coordination with the Russian position with reference to both the pandemic and US biological research activities abroad in the previous decades.

Such a move toward the Russians, however, was quite significant, if not shocking, even compared with early January when Prof.Feng Shaolei, perhaps the most prominent Russologist in China, still described the US-China-Russian dynamics as “fluid, flexible, and complex.” By the end of April, however, the triangle seemed more asymmetrical and less flexible as Moscow and Beijing were visibly moving toward each other vis-à-vis Washington.

For Hu Xijin, the Global Times editor, the Sino-Russian strategic partnership would have never matured as rapidly had the US and the West intended to form genuine friendship with China and Russia. In this sense, Moscow-Beijing ties are shaped by the “storms of our era,” said Hu.

For this author, who had until the end of last year depicted the Beijing-Moscow strategic partnership as one of deliberately avoiding an alliance, the era of cautious strategic distancing appeared over. The next few months could be more interesting, and precarious, as the US presidential election unfolds in conjunction with a high infection and death rate. Blaming China for the dire consequences of the pandemic will only intensify.

The emerging US-China confrontation may provide Russia with strategic space, observed Feng Yujun, a senior Russia specialist in Fudan University in Shanghai. Some in Russia have been longing for a posture of greater equilibrium in the post-pandemic world.

For Russians, who seem inherently pessimistic, the world is “heading into a storm as dangerous as that of the first half of the 20th century and maybe even more so,” said Alexander Solovyov, a historian and orientalist in Moscow. Solovyov dismissed the view that history was an adequate guide for future challenges for Russia. He was nonetheless worried that “[I]f the Anglophone-dominated world failed to manage peacefully the rise of semi-liberal, entirely capitalist and European Germany before 1914, then one would expect the problem of finding a worthy place for China in today’s global order to be much harder … Survival seems likely to be the key issue.”

Jan. 7, 2020: Russia and China block UN Security Council statement on the US embassy bombing in Iraq, insisting that any statement by the UNSC on the attack on the embassy in Baghdad should also include the latest developments (including Soleimani’s killing).

Jan. 16, 2020: Mikhai Mishustin is named Russia’s new prime minister.

Jan. 16, 2020: Chinese foreign ministry spokesman Geng Shuang says that the resignation of Medvedev’s Cabinet was “Russia’s internal affair,” and China completely respects the Russian decision.

Jan. 23, 2020: Russian President Vladimir Putin proposes a summit between leaders of the permanent members of the UNSC (Russia, China, the United States, France, and Britain) in 2020 to discuss global problems.

Jan. 24, 2020: Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying expresses support for Putin’s proposal of holding a summit of the UNSC permanent members.

Jan. 31, 2020: Putin sends a message to Chinese President Xi Jinping expressing sympathy and support for coronavirus victims.

Jan. 31, 2020: Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin issues an order to extend the closing of five port entrances in Russia’s Far East bordering China to prevent the spread of coronavirus.

Feb. 1, 2020: Russian Aerospace Forces are authorized to evacuate Russian citizens from the “most affected” areas of China by the coronavirus.

Feb. 1, 2020: Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov speaks by phone with Chinese counterpart Wang, saluting the measures China has taken in fighting the coronavirus.

Feb. 3, 2020: Mishustin announces that Russia would provide humanitarian aid to China for combating the COVID-19 outbreak.

Feb. 5, 2020: Russia sends its first shipment of medical supplies to Wuhan to assist China’s anti-virus effort there.

Feb. 5, 2020: Putin receives letters of credence from 23 newly appointed foreign ambassadors in the Kremlin, including Chinese Ambassador to Moscow Zhang Hanhuit, and says that Russian relations with China are “at an unprecedentedly high level.”

Feb. 9, 2020: Russia’s Ministry of Emergency Situations sends 23 tonsof medical supplies to Wuhan.

Feb. 11, 2020: Russian BRICS Chairmanship issues a statement on behalf of other members of the group for supporting China’s effort against the coronavirus pandemic.

Feb. 15, 2020: Lavrov and Wang meet on the sidelines of the 56th Munich Security Conference in Germany, where Lavrov promises that Russia would continue to provide humanitarian assistance to China.

Feb. 18, 2020: Russia declares that from February 20 it would “temporarily prohibit” the entrance of Chinese citizens from entering Russia with permits for work, private visit, study, and tourism, and also close its port entrances with China.

March 10, 2020: Foreign ministers of China, France, Russia, UK, and the US issue a joint statement on the 50th anniversary of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons reaffirming their commitment to the NPT “in all its aspects.”

March 17, 2020: Putin tells Russian officials in the Kremlin that Russia has managed to contain the “massive penetration and spread of the infection in Russia,” and that “the situation is generally under control.”

March 25, 2020: Russia and China take part in a joint address (with Venezuela, Iran, North Korea, Cuba, Nicaragua, and Syria) to the UN secretary general urging withdrawal of unilateral sanctions during the spread of the coronavirus pandemic.

April 2, 2020: China sends 26 tons of medical equipment to Russia.

April 6, 2020:Chinese embassy in Moscow informs Russian foreign ministry that to prevent the cross-border spread of COVID-19, China is temporarily closing the passenger corridor at the Suifenhe checkpoint effective April 7.

April 11, 2020: China sends a group of medical exports Russia.

April 14, 2020: Lavrov holds a phone call with Wang, discussing the pandemic and other issues. In his press briefing following the call, Lavrov warns against politicizing the coronavirus issue and says it is “beyond the pale” for the West to demand payment for Chin “spreading the virus.”

April 16, 2020: Xi and Putin conduct a telephone conversation focusing on the coronavirus, with Xi promising China’s strong support to Russia and hoping Russia would help Chinese citizens living in Russia.

April 17, 2020: China’s ambassador to Russia Zhang tells TASS that a gene sequence in the coronavirus indicated that the virus was imported to China’s Wuhan, instead of emerging there.

April 23, 2020: Russian foreign ministry spokesperson Maryana Zakharova calls Western accusation that China is the source of the coronavirus pandemic “absolutely inappropriate.”

April 28, 2020: BRICS foreign ministers take part in a video conference chaired by Lavrov. They agree to enhance collaboration to fight the COVID-19 pandemic, and to create a special credit mechanism with a total of $15 billion allocated to finance economic recovery projects.

April 28, 2020: Lavrov dismisses EU criticism of Russia and China over disinformation, and speaks highly of China’s efforts to contain the virus inside China, as well as its support for Russia and other countries.

April 29, 2020: Mishustin is diagnosed with COVID-19 and First Deputy Prime Minister Andrey Belousov is appointed interim head of government.

April 29, 2020: Chinese foreign ministry spokesman Geng Shuang says Washington must pay special attention to issues that have a direct bearing on the health and well-being of the people in countries where US laboratories are located, referring to a statement by Russian foreign ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova on April 17.