Articles

For Moscow and Beijing, relations with Washington steadily deteriorated toward the yearend. This was in sharp contrast from early 2021 when both had some limited expectations for relaxed tensions with the newly inaugurated Biden administration. For Russian President Vladimir Putin and his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping, each of their meetings (real and virtual) with Biden was frontloaded with obstacles: US sanctions, a boycott of the 2022 Winter Olympics, and screw-tightening at strategic places (Taiwan and Ukraine). Biden’s diplomacy-is-back approach—meaning US-led alliance-building (the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue and AUKUS for China) or reinvigorating (NATO for Russia)—turned out to be far more challenging than Trump’s erratic go-it-alone style. It was against this backdrop that China and Russia enhanced their strategic interactions in the last few months of 2021, particularly mil-mil relations at a time of rising tensions in the western Pacific.

In the Democratic Crosshairs

In their virtual summit on Dec. 15, described as “the highest level of mutual trust, coordination, and strategic value between major countries,” Putin and Xi vowed to take coordinated actions in political, economic, and strategic areas at all levels. The 90-minute video summit also covered plans to establish a new independent financial framework outside the US-controlled SWIFT transaction system and joint development of “certain high-tech types of weapons” in aerospace.

Referring to relations with China as “a shining example of interstate cooperation in the 21st century,” Putin spoke highly of the official extension for another five years of the “Treaty of Good Neighborliness and Friendly Cooperation between the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China.” Xi echoed Putin’s positive assessment of bilateral ties, adding that China “highly appreciated” Putin’s “strong support” for China’s effort to safeguard its “core interests” as well as Putin’s opposition to “attempts to divide (间离) Russia from China.”

This was the third video conference in 2021 for the two leaders, the other two being May 19, for launching Russian nuclear power units in China, and June 28, when they officially extended their treaty another five years. Xi and Putin talked over the phone on Aug. 25 about the situation in Afghanistan.

The Dec. 15 video conference devoted a considerable amount of attention to domestic issues. Referring to China’s “ambitious yet modest goal” as “allowing the Chinese people to have a good life,” Xi pledged China’s “resolute support” for Russia’s effort to safeguard its security and stability.” “As large powers with global influence, both China and Russia have found their paths suitable for their national characteristics,” said Xi, adding that he was for more frequent exchanges with Putin regarding the “philosophy of governance (治国理念)” for national rejuvenation of the two countries. For Putin, this “new model of cooperation,” an “absolutely comprehensive partnership of strategic nature,” was based on “the principles of non-interference in each other’s affairs and a mutual resolve to turn our common border into a belt of eternal peace and good-neighborliness.”

Figure 1 Chinese President Xi Jinping holds a virtual meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Beijing, capital of China, Dec. 15, 2021. Photo: Xinhua

The emphasis on domestic stability in Putin-Xi talks took place shortly after a US-sponsored democracy summit on Dec. 9-10 with over 100 world leaders and activists, not including China or Russia. They were certainly among the targets of the $424 million earmarked for democracy promotion around the world by the US government. Shortly before the democracy summit, Washington declared a political boycott of the February 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics.

“(It is) only up to the people of a nation to decide whether it is a democracy and how to better achieve democracy,” said Xi to Putin during the December video conference. The summit meant Washington’s right to impose its view of democracy on others and its unwillingness to accept the sovereign equality of all countries, remarked Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov. “We invariably support each other in every aspect of international sports cooperation, including in condemning any attempts to politicize sports and the Olympic movement. I have no doubt that the upcoming Winter Games will be held at the highest level,” Putin informed Xi.

In late November, Russian and Chinese ambassadors to the US (Anatoly Antonov and Qin Gang) took an unusual step and jointly wrote an article in the influential National Interest, warning that the democracy summit would lead to ideological confrontation when countries needed to strengthen cooperation to deal with global challenges. “No country has the right to judge the world’s vast and varied political landscape by a single yardstick, and having other countries copy one’s political system through color revolution, regime change and even use of force,” argued the ambassadors. “A truly democratic government will support democracy in international relations.”

“Unlimited” Strategic Coordination?

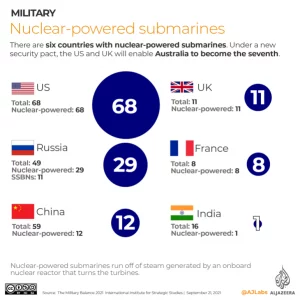

A key issue area for China-Russia diplomatic and strategic coordination was the arrival on Sept. 15 of the AUKUS triad (Australia, the UK, and the US). The multi-billion dollar deal for eight nuclear submarines for Australia in the next decade or two represents a typical case of asymmetrical threats for China and Russia. It was a significant step toward militarization of the US-led Indo-Pacific concept against China’s core interests. Meanwhile, Russia remains either neutral (the South China Sea, Diaoyu/Senkaku, etc.) or noncommittal (such as Taiwan) on issues due to a lack of an alliance arrangement with China.

Figure 2 The current number of nuclear-powered submarine by country, soon to include Australia. Photo: The Military Balance 2021, IISS, Sept. 21, 2021. Reprinted from Al Jazeera

In the military-technology domain, the Russian-China asymmetry regarding AUKUS is more striking. The future Australian nuclear sub fleet may not add too much to the US’ own powerful underwater capability. For the PLA Navy, however, nuclear subs—either nuclear-powered or nuclear-armed—remain an area of underdevelopment relative to its US and Russian counterparts.

Given these asymmetries, Russia’s reaction and response to AUKUS were swift and steady. Six days after its debut, Russian Security Council Secretary Nikolai Patrushev defined AUKUS as both anti-China and anti-Russia. Referring to the US move as “reckless,” Patrushev slammed AUKUS as “another military bloc in the region” in addition to the Quad, which jeopardized “the entire security architecture of Asia in a bid to strengthen its control over the promising Asia-Pacific region.”

In early October, Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov, too, voiced strong criticism of AUKUS: “The so-called Indo-Pacific strategies (including the Quad and AUKUS) that are invented by the United States are eroding the universal formats in the Asia-Pacific Region which existed for the past decades under the auspices of ASEAN.” President Putin himself weighed in on Oct. 14, saying that the initiative undermined regional stability.

By late October, when Lavrov met with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi on the sidelines of the G20 summit in Rome, the two diplomats “expressed serious concerns on the nuclear submarine deal and that AUKUS is a “typical military group.” To oppose such a “narrow-bloc organization,” Lavrov and Wang proposed a summit of permanent members of the UN Security Council “at the soonest possible time in order to seek an effective response to current global challenges and threats.”

The UN Security Council was perhaps a bridge too far for the budding AUKUS threat. For Russia and China, closer strategic coordination was a more viable approach to the volatile situation. “In the age of global instability and turbulence, China and Russia resolutely support each other for the dignity and interests of both sides,” remarked Xi in his teleconference with Putin in mid-December. For the Russian president, the “responsible joint approach to current global problems” has become “a significant factor of stability in international relations.”

In early December, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergey Ryabkov made it more explicit that Russia can’t “sit on its hands” and do nothing to deepen strategic ties with China under “conditions when both countries have come under identical and increasingly heavy pressure from the collective West.” For this, Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Le Yucheng reiterated a relatively novel definition for Sino-Russian strategic interaction of “three nos”: “no end lines, no forbidden areas, and no upper limits” (没有止境, 没有禁区, 没有上限). It was first articulated in early January 2021 by Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, meaning an open-ended, flexible, and convenient way to transcend the rigid and restrictive alliance format for the two large independent powers.

Russia and China in Hypersonic Drive

The defense issue was part of the Xi-Putin videoconference on Dec. 15, according to Russian media. In his annual press conference on Dec. 23, Putin revealed a bit more: “We are cooperating in the field of security. The Chinese (a)rmy is equipped to a significant extent with the world’s most advanced weapons systems. We are even developing certain high-tech weapons together,” the Russian leader went on.

While annual land and naval exercises between the two militaries have become routine, joint missile defense simulation is relatively new (starting from 2016). In Dec. 2019, Putin announced that Russia was helping China to develop its national missile attack warning system. By August 2020, “certain successes” were achieved including “space control,” according to Sergei Boyeve, CEO of Vimpel Company, chief designer of Russia’s missile attack warning system. It is unclear if COVID has slowed the process. By late September 2021, Russian media noted that some of China’s DF-41 ICBMs (mobile, MIRV-capable, 12,000-15,000 km range) were deployed close to the Russian border, which meant being protected by the joint missile defense system both on the ground and presumably in their early flight path over Siberia.

Figure 3 DF-17 on parade in Beijing, Oct. 1 2019. Photo: PLA via CSIS

Figure 4 Russia’s Tsirkon hypersonic missile. Photo: The National Interest

It was unclear if Putin’s reference to China’s “world’s most advanced weapons systems” included China’s reusable hypersonic glide missile successfully tested in August 2021, which was reported by Chinese and Russian media. Despite China’s dismissal of the test as a reusable space vehicle for peaceful purposes, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Mark Milley said on Oct. 27 that the test was close to a “Sputnik moment.” According to one US estimate, the US did nine hypersonic tests in 2016-2021 while “the Chinese have done hundreds.”

Hypersonic weapons are normally defined as fast, low-flying, and highly maneuverable weapons designed to be too quick and agile for traditional missile defense systems. In 2019, China deployed DF-17s, a hypersonic medium-range ballistic missile (1800-2,500 km range, Mach 5-10) that mounts the DF-ZF hypersonic glide vehicle (HGV). Russia claimed to deploy in 2018 the Tsirkon (Циркон) anti-ship hypersonic cruise missiles (Mach 9, 1,000 km range).

Both Russia and China are ahead of the US in R&D for and deployment of their own hypersonic devices. There are no signs of any joint effort in this area. The goal, however, is similar: to evade the US missile defense systems. Putin, who spoke highly of Russia’s Tsirlon systems in the last few months of 2021, seemed well-informed about China’s parallel progress in HGV.

Beyond this, Sino-Russian mil-mil interactions were uninterrupted in the last few months of 2021. On Nov. 23, Chinese Defense Minister Wei Fenghe held a videoconference with Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu. A statement released after the talks said that the two militaries had in 2021 deepened cooperation in various fields, with “new breakthroughs” in the field of joint exercises and training in particular.

Figure 5 Chinese troops participate in the closing ceremony of the “Peace Mission 2021” counter-terrorism military drill of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) member states on Sept. 24, 2021. Photo: Xinhua

On Sept. 20-24, the SCO conducted “Peace Mission 2021,” a counter-terrorism military exercise, at the Donguz training range in the Orenburg Region in Russia’s southern Urals. The annual drill involved about 5,500 servicemen and over 1,200 pieces of weaponry, military, and special vehicles. In addition to SCO member states, Belarusian units took part for the first time. China sent 550 troops and 130 pieces of equipment. The four-day drill practiced anti-drone warfare and methods of preventing terror attacks involving the use of chemical and biological weapons. It was conducted shortly after the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan. A key element of this drill was to test and improve coordination and rapid reaction capability of SCO anti-terror units.

Red October?

On Oct. 1, Putin sent a telegram to Xi on the 72nd anniversary of the PRC’s founding. Russia-China cooperation “contributes to greater security and stability at the regional and global levels,” noted Putin. The month of October, however, turned to be hectic if not hazardous, particularly in the western Pacific.

Between Oct. 14 and 17, Russian and Chinese navies conducted the annual Maritime Interaction 2021 near Russia’s Peter the Great Gulf in the Sea of Japan. Five Chinese naval vessels, including the Type 055, 10,000 ton-class Nanchang destroyer, joined this 10th naval exercise with Russia with a declared goal of “security maintenance of strategic maritime corridor” (维护海上战略通道安全). The two navies practiced more than 20 different combat exercises including communications, sea mine countermeasures, air defense, live-fire shooting at maritime targets, joint maneuvering, and joint anti-submarine missions, according to Russia’s Defense Ministry.

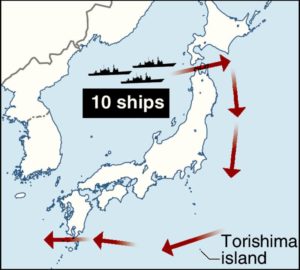

Figure 6 An overview of the passage taken by ten Russian and Chinese warships through the Tsugaru Strait and Osumi Strait following joint naval exercises. Photo: Kantie.org

Joint drills between China and Russia have become routine and are completely normal, commented Li Shuyin of PLA Academy of Military Sciences. What happened after the annual naval exercises, however, was quite unusual. Immediately after the drill, the 10 participating warships of the two navies passed the narrow (20-km-wide) Tsugaru Strait (津轻海峡) for a first-ever joint sail around the Japanese archipelago. During what the Russian media called “patrol in the western Pacific” between Oct. 17 and 23, the Russian-Chinese naval formation jointly practiced tactical maneuvering and drills. On Oct. 22, the ships entered the East China Sea through the 40 km-side Osumi Strait (大隅海峡) after covering 1,700 nautical miles.

The joint naval patrol complemented the joint aerial patrol by Russian and Chinese bombers over the Sea of Japan and the East China Sea that started in 2019. On Nov. 19, Russian and Chinese bombers conducted their third patrol.

The annual naval drill and the joint naval and aerial patrols came as the Quad (the US, India, Australia, and Japan) were holding the Malabar naval drill in the Bay of Bengal, as well as the Maritime Partnership Exercise (MPX) 2021 with the US, the UK, Australia, and Japan in the South China Sea. In both cases, Japan was an active participant. Under Prime Minister Fumio Kishida who assumed office on Oct. 2, the ruling LDP has discussed doubling defense spending to 2% of GDP, or about $100 billion, citing China’s threat. Meanwhile, top Japanese officials increasingly expressed a willingness to fight for Taiwan, which was taken from China by Japan after the 1894-95 Sino-Japanese War and returned after Japan’s surrender to allied forces in 1945. The unexpected joint patrol around the Japanese main islands may well be a convenient reminder to Japan of its strategic location in the highly sensitive northeast Asia. Back in 1950, Japan was the only designated target of the Soviet-China Treaty of Alliance. A replay of the early Cold War is unlikely in the 21st century. There is, however, an emerging faultline between continental and maritime powers.

October wouldn’t be truly eventful without the US. On Oct. 2, the USS Connecticut, perhaps the most sophisticated and most expensive nuclear attack submarine in the world, struck an underwater seamount in the South China Sea, resulting in serious damage to its sonar dome. It is still unclear how it happened. The incident underscored the highly intensive, and dangerous, underwater operations in the western Pacific, given the growing rivalry between major powers.

China’s Foreign Ministry repeatedly complained about Washington’s failure to provide detailed information on the collision. Russia, however, got what it did not want from the US. At the height of the Russia-China naval exercise off the Peter the Great Gulf on Oct. 15, the Russian Navy reportedly thwarted an attempt to intrude into Russian territorial waters by the missile destroyer Chafee. The real task of the US destroyer was to monitor the China-Russia naval gunnery drills near Russian waters that were declared off-limits to shipping. The Russian Defense Ministry summoned the US Naval attaché in Moscow to protest the “unprofessional actions of the American crew.”

Figure 7 Chinese and Russian warships transit simulated mined sea area during October 2021 naval exercises. Photo: Xinhua

Putin’s “Taiwan Moment”

The Cold War-style “Tom-and-Jerry” game between the US and Russian navies was risky but largely regulated. The growing naval activities in the western Pacific, however, occur as the Taiwan issue is becoming increasingly contentious, to the extent that even Russian President Putin weighed in. On Oct. 13, a day before the China-Russia naval exercise, Putin told CNBC’s Hadley Gamble in Moscow that China “does not need to use force” to achieve its desired “reunification” with Taiwan. “China is a huge powerful economy, and in terms of purchasing parity, China is … number one in the world ahead of the United States now … By increasing this economic potential, China is capable of implementing its national objectives. I do not see any threats,” said Putin, who also cited China’s “philosophy of statehood and management that do not include the use of force.”

Rarely did Putin comment on the Taiwan issue in such an unconventional and philosophical manner. It came just four days after a conciliatory tone by President Xi at a rally in Beijing commemorating the 110th anniversary of the 1911 Republican Revolution. “National reunification by peaceful means best serves the interests of the Chinese nation as a whole, including compatriots in Taiwan,” declared Xi.

It was unclear if Putin and Xi coordinated their positions regarding Taiwan. The combined effect of their remarks, however, applied something of a brake to the accelerating momentum toward the Taiwan “trap” in 2021, that started from the Trump administration’s decision in its last week, to lift all the restrictions between US and Taiwan officials. This situation appeared so dangerous that JCS Chairman Gen. Mark Milley—who was afraid that Trump “might order the launch of some sort of military strike that would set off a chain reaction and lead to war”—called Gen. Li Zuocheng of China on Jan. 8, 2021, two days after the Capitol Hill riot, to defuse the crisis. To China’s dismay, Biden not only did not reverse Trump’s decree but proceeded to operationalize it with more frequent official interactions with Taiwan officials. In early August, Biden approved his first arms sale to Taiwan ($750 million). In the first eight months of the Biden administration, the US sent warships through the Taiwan Strait eight times.

The fall of Afghanistan in late August was felt more intensely in Taiwan than anywhere else in the world. Chinese media quickly pointed to the “Afghan lesson” for Taiwan as a US “strategic pawn.” The 21st century “Saigon moment,” no matter how chaotic, actually allowed the US to refocus on major power (China) competition. Russian media, however, argued that repercussions from the disastrous Afghan exit would make Washington’s refocus on China impossible.

The post-Afghan months witnessed a new round of posturing between Washington, Beijing, and Taipei, plus Moscow’s newfound interest. On Oct. 6, National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan and his Chinese counterpart Yang Jiechi met in Zurich. Sullivan reportedly “expressed its adherence to the one-China policy” (the White House readout, however, does not have this statement). Xi’s reiteration of the peaceful means for reunification three days later was followed by Putin’s Taiwan remarks to CNBC. On Oct. 22, the White House spokesperson went so far as to “clarify” Biden’s vows to defend Taiwan in a live CNN town hall meeting that Biden “was not announcing any change in our policy.”

The triangular efforts by all three large powers to manage the Taiwan impasse may not go far, given the growing indigenous movement in Taiwan for separation. On Oct. 28, Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen revealed that a small number of US military personnel were already in Taiwan for some time to train with local forces.

China was furious. There were no Russian official comments on Tsai’s remarks. RT, however, quickly pointed out that no such provision (defending Taiwan) in the 1979 Taiwan Relations Act, which governs US relations with the island. Oddly enough, Putin’s Taiwan remarks to CNBC were not part of the Kremlin official transcript. Putin’s creative take-up of the Taiwan issue highlighted Moscow’s deep concerns regarding Taiwan’s future in Russia’s strategic matrix in the western Pacific.

Whatever the case, the Taiwan issue was back in uncharted waters.

Soviet Collapse 30 Years After

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 “was a tragedy for the vast majority of the country’s citizens,” lamented Putin as part of a TV documentary on modern Russian history aired shortly before the 30th anniversary of that event. This was not the first time that Putin lamented the Soviet fall. In 2005, he called the event “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century” (крупнейшей геополитической катастрофой века). Putin’s nostalgia led to the assertion by US Undersecretary of State Victoria Nuland that the Kremlin wanted to recreate the Soviet Union. “Mrs. Nuland understands perfectly well that the restoration of the Soviet Union is impossible,” Putin’s spokesman Dmitry Peskov responded.

For Zhao Huasheng, a leading Russologist in Shanghai, the Soviet fall meant a structural change of the international system, not necessarily along a linear trajectory but like a pendulum after its peak (unipolarity and liberal international order), to another round of the Cold War primarily with China.

Russia, however, was never outside this new round of the Cold War, or hot peace. On Dec. 17, Russia officially presented to NATO draft documents on comprehensive security guarantees, including the principles of equal security and no further eastward expansion by NATO, which, according to Peskov, “a matter of life and death for us.”

“The boot is on the other foot every 30 years” (三十年河东三十年河西), goes a popular Chinese saying. The new Cold War, however, “won’t be a simple repetition of the old one,” argued Zhao Huasheng at the 30th anniversary of the Soviet collapse on Christmas Day 1991. “It will be colder in some aspects,” added Zhao.

Both China and Russia had in three decades departed significantly from their political extremes and returned, to different degrees, to their cultural/religious heritages: Confucianism for China (CCP as the “Chinese Civilization Party,” according to Mahbubani) and “moderate conservatism” for Russia with a hefty dose of Eastern Orthodoxy. Meanwhile, de-ideologization in foreign policy meant a historical return to Westphalianism of noninterference in each other’s domestic affairs, the foundation of the modern world system of sovereign states, allowing a steady improvement of their bilateral ties.

The 30th anniversary of the Soviet implosion, however, played out very differently for Washington, which found itself battling China and Russia abroad and politico-ideological polarization at home. This was ironic in that both Moscow and Beijing were friends of Washington 30 years ago.

For China and Russia, the weakening of the international system meant uncertainty and insecurity, fueled by a toxic mix of the pandemic, populism, and the proliferation of WMD of all kinds, and the inclusion of AI. In early November, Henry Kissinger, architect of the Cold War strategic triangle between Washington, Moscow, and Beijing, warned against the catastrophic prospect of a US-China conflict due to miscalculation, AI, and nuclear weapons.

It is unlikely that the three large powers will return to the good old days of the Cold War “long peace.” At the onset of 2022, however, a glimpse of hope appeared when five permanent members of the UNSC signed a joint statement pledging that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.” It remains to be seen if this unusual joint action by the world’s most powerful nations will reduce the stress in a highly stressful world in the new year.

Sept. 3, 2021: Shanghai Cooperation Organization finance ministers hold fourth meeting via videoconferencing chaired by SCO’s rotating chair Tajikstan.

Sept. 3, 2021: Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi and Russian counterpart Sergey Lavrov send their statements to the Fort Dong Ning Museum in China’s northeastern Heilongjiang Province to commemorate the last battle of the Soviet Red Army in World War II.

Sept. 9, 2021: BRICS leaders hold 13th summit via video, with a joint statement issued after the meeting. Russia, Brazil, South Africa and India supported the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics. China took over the chair of the 14th BRICS summit in 2022.

Sept. 15, 2021: Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Le Yucheng meets Russian Ambassador to China Andrey Denisov in Beijing. They discussed Afghanistan and other bilateral and global issues.

Sept. 16-17, 2021: SCO holds 21st session of its heads of state, via videoconference, in Dushanbe under chairmanship of President of Tajikistan Emomali Rahmon. Chinese FM Wang Yi met Russian counterpart Lavrov on the sidelines of the summit. An informal meeting on Afghanistan was held by Chinese, Russian, Pakistani, and Iranian foreign ministers as well.

Sept. 20-24, 2021: SCO conducts “Peace Mission 2021,” a counter-terrorism military exercise, at the training range in the Orenburg Region in Russia’s southern Urals. 5,500 troops, including 550 Chinese servicemen and, for the first time, Belarusian units, participated. Anti-drone warfare was part of the annual drill.

Sept. 21-22, 2021: Chinese, Russian and Pakistani special envoys visit Kabul and met the acting head of Afghanistan’s Taliban-led government, Mullah Muhammad Hassan Akhund.

Sept. 21-Oct. 4, 2021: SCO law enforcement forces hold second stage of “Pabbi Antiterror-2021” Joint Anti-Terrorism Exercise (JATE) in the Pakistani city of Pabbi. The first stage of the drill was conducted by simulated exchanging, sharing, collection, and evaluation of anti-terrorism intelligence within SCO members’ borders. India did not join the exercise.

Oct. 1, 2021: Putin sends telegram to Xi on the 72nd anniversary of the establishment of the PRC.

Oct. 7, 2021: Chinese and Russian foreign ministers release a joint statement to the UN calling for the US to abide by a UN convention on biological weapons.

Oct. 11, 2021: President Xi sends a message of condolence to President Putin over the crash of a Russian plane.

Oct. 12, 2021: Russian FM Lavrov says that “Russia, like the overwhelming majority of other countries, considers Taiwan to be part of the People’s Republic of China. We have proceeded and will proceed from this premise in our foreign policy.”

Oct. 13, 2021: Putin tells CNBC’s Hadley Gamble that China “does not need to use force” to achieve its desired “reunification” with Taiwan. Regarding the South China Sea, Putin said that “we need to provide an opportunity for all countries in the region, without interference from the non-regional powers, to have a proper conversation based on the fundamental norms of international law…” Putin’s Taiwan remarks were not part of the Kremlin official transcript.

Oct. 14, 2021: At the initiative of India, the SCO holds its first seminar, via video conference, on the role of women in the armed forces.

Oct. 14-17, 2021: Russian and Chinese navies conduct Maritime Interaction 2021 off the Peter the Great Gulf in the Sea of Japan.

Oct. 17-23, 2021: Ten Russian and Chinese warships, which just concluded the Maritime Interaction 2021 naval drill in the Sea of Japan, conduct first-ever joint patrol around the Japanese archipelago.

Oct. 26, 2021: State Duma ratifies a protocol extending, until Dec. 16, 2030, a Russia-China deal on notifying each other of ballistic missile and carrier rocket launches.

Oct. 30, 2021: Lavrov and Wang meet in Rome on the sidelines of the G20 summit. Putin and Xi decline to join the meeting. The two diplomats praised the state of the Russian-Chinese strategic partnership and proposed convening a UNSC permanent members’ summit.

Nov. 3, 2021: Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Ma Zhaoxu speaks with Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov on the phone about the Iran nuclear issue.

Nov. 8, 2021: Russia and China sign contract for the joint development of a heavy helicopter, Andrey Boginsky, head of the Russian Helicopters holding, says at a meeting with Putin.

Nov. 10, 2021: Cheng Guoping, external security commissioner of China’s Foreign Ministry, meets in Beijing with Russian Ambassador to China Andrey Denisov. They have an in-depth exchange on issues such as China-Russia relations and global counter-terrorism cooperation.

Nov. 11, 2021: Envoys of the Troika Plus meeting (Russia, Pakistan, China, and the US) meet in Islamabad, urging the Taliban to cut ties with terrorist groups and deprive them of the opportunity to act on Afghan territory.

Nov. 16, 2021: China-Russia Consortium Global Space Weather Center is operational. It monitors space weather events including solar activities and releases advisories for aviation operators, and provides services for aviation operators around the world. This is the fourth such center approved by the UN International Civil Aviation Organization to coordinate platforms in civil aviation. The other three are run by an Australian, Canadian, French, and Japanese consortium; a European consortium; and the United States.

Nov. 19, 2021: Two Russian Tu-95MC and two Chinese H-6K strategic bombers conduct their third joint air patrol over the Sea of Japan and the East China Sea in the Asia-Pacific region.

Nov. 19, 2021: Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Ma Zhaoxu, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov, and US Special Envoy for Iran Robert Malley exchange views on the Iranian nuclear issue via a videoconference.

Nov. 25, 2021: SCO holds its 20th prime ministerial meeting via videoconference. Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin and Chinese Premier Li Keqiang joined the meeting.

Nov. 26, 2021: Russian and Chinese ambassadors to the US (Anatoly Antonov and Qin Gang) jointly publish an article in National Interest regarding the US-sponsored democracy summit.

Nov. 26, 2021: Xi sends condolences to Putin after a coal mine explosion in Russia that caused heavy casualties.

Nov. 26, 2021: Putin and Xi send congratulations in the closing of the Sino-Russian Year of Scientific and Technological Innovation.

Nov. 26, 2021: Russian, Indian, and Chinese foreign ministers hold their 18th meeting via videoconference. A joint statement was issued after the meeting.

Nov. 29, 2021: Xi and Putin send congratulatory messages to the 3rd Sino-Russian energy forum.

Nov. 30, 2021: Putin discusses China during an investment forum in Russia. Speaking highly of China’s development and Russian-China relations, Putin also strongly criticized US-led alliances and sanctions against China.

Nov. 30, 2021: Chinese Premier Li Keqiang holds the 26th Regular Meeting with Russian Prime Minister Mishustin via videoconference, where they focused on economic and other bilateral issues. A joint statement was issued after the meeting.

Dec. 2, 2021: Chinese Vice FM Le Yucheng and Russian Deputy FM Morgulov Igor Vladimirovich hold video conference. Both criticized the US-sponsored Democracy Summit.

Dec. 8, 2021: Vice FM Ma Zhaoxu, Russian Deputy FM Sergei Ryabkov and US Special Envoy for Iran Robert Malley hold a teleconference on the Iranian nuclear issue.

Dec. 15, 2021: Putin holds talks, via videoconference, with Xi Jinping.

Dec. 28, 2021: Russia’s Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Chernyshenko says that countries staging a diplomatic boycott of the Beijing Winter Olympics should have their flags and anthems removed while taking part in the spectacle.

Dec. 30, 2021: Chinese FM Wang Yi pens article in People’s Daily opposing “color revolutions” in central Asia.

Dec. 31, 2021: Xi and Putin exchange New Year’s messages.