Articles

China faced a less forceful US posture in the South China Sea in this reporting period compared with earlier in 2020. Beijing took advantage of President Trump’s failure to participate in the East Asian Summit (EAS) and other ASEAN-led meetings in November. Chinese leaders depicted the United States as disruptive and out of step with what Beijing saw as an overriding trend toward regional economic integration and cooperation. They highlighted the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement and ASEAN’s new prominence as China’s top trading partner, forecasting stronger regional economic growth led by China’s rapid rebound from the COVID-19 pandemic. Beijing remained on guard against US challenges, and it resorted to unprecedented trade retaliation and related diplomatic pressures to compel Canberra to change its recent moves to check Chinese interference in domestic Australian affairs, expansionism in the South China Sea, repression in Hong Kong and Xinjiang, and malfeasance in the initial handling of the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Some experts were optimistic that the Philippines and China were on the verge of agreeing on joint exploitation of oil and gas in South China Sea areas claimed by both countries, but others remained skeptical.

Dueling US-Chinese military exercises in the South China Sea and related Chinese warnings of military conflict featured earlier in 2020 declined in this reporting period. Nevertheless, the extraordinary US naval exercises in the South China Sea in July were followed in September by large military excises by China in the South China Sea and three other locations along the China coast to show resolve against the United States and its allies and partners. China’s Ministry of National Defense spokesman criticized Japan for carrying out anti-submarine drill with Vietnam in the South China Sea in October.

Figure 1 Image of the 2020 Malabar Exercise. Photo: Indian Navy/Twitter

Chinese media were critical of the related annual Malabar military exercise in November, carried out near the western entry of

the Malacca Strait and involving the United States, India, Japan and, for the first time, Australia. There also were routine Chinese reactions to US Freedom of Navigation Operations. On Dec. 23, China Daily reported the US destroyer USS John S. McCain was “expelled” while it “trespassed” in waters claimed by China in the Spratly Islands, noting that the same warship had been similarly countered when conducting operations in Chinese-claimed waters in the Paracel Islands in October. The report added that prior to its operations in the Spratly Islands, the US warship had been conducting operations in the Philippines Sea with a French submarine and a Japanese helicopter carrier.

Reuters and Japanese media reported there would be further exercises among the three militaries in May, with the chief of staff of the French Navy saying that “This is a message aimed at China…This is a message about multilateral partnerships and the freedom of passage.” Coinciding with the US warship operation in the Spratly Islands, China sent the aircraft carrier Shandong and support warships through the Taiwan Strait and into the South China Sea for “long-distant training operations.”

Meanwhile, sharp Chinese criticisms targeted Secretary of State Michael Pompeo and National Security Adviser Robert O’Brien visiting the region. Chinese officials had little to say about O’Brien at the East Asian Summit (EAS) or President Trump at the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit.

Depicting the United States as ineffective and out of step with regional priorities, Chinese leaders doubled down on China’s closer economic integration with Southeast Asian countries, notably through the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement reached in conjunction with the East Asia Summit in November. They reassured regional states of Chinese intentions, highlighting growing China-ASEAN trade and investment, financing with China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and Chinese support for regional countries in dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic. They forecast a future of ever-closer regional ties in opposition to perceived disruptive practices by the US. The main exception was Australia, whose strong alignment with the United States and criticisms of Chinese government practices in Australia and the region prompted unprecedented restrictions on Chinese trade, student, and tourist exchanges, along with strong diplomatic and media pressure.

Chinese Leadership at Annual Asian Regional Meetings

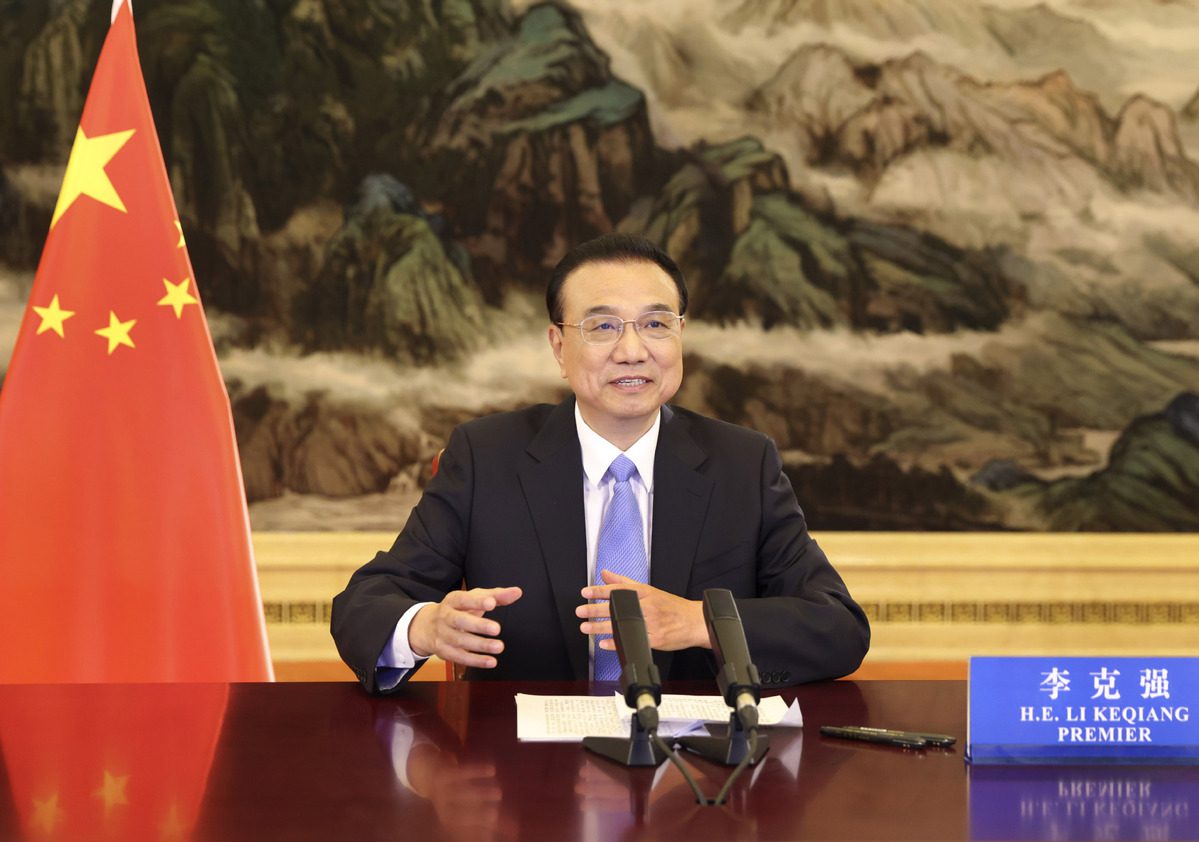

As in the past, Premier Li Keqiang represented China at the East Asian Summit and other related head of government annual meetings, including the ASEAN Plus 3 and the China-ASEAN summit, hosted virtually this year by Vietnam as ASEAN chair. His comments set the tone and major themes of what would turn out to be a substantial Chinese publicity effort highlighting China as regional leader with the United States marginalized as a disruptive outsider.

Figure 2 Premier Li Keqiang delivers a speech via video at the ASEAN Business and Investment Summit in Beijing on Nov 13, 2020. Photo: Xinhua

Speaking at the ASEAN Business and Investment summit on Nov. 13, Li stressed China’s exceptional recovery from the COVID pandemic. He said this allowed for positive economic growth and “taking the lead” in providing opportunities for regional economies seeking to rebound from recession. The RCEP trade agreement reached on Nov. 15 by Li and the 14 other government leaders, represented all ASEAN members, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand. Li said RCEP was a “victory of multilateralism and free trade.” He acknowledged ASEAN countries played an “important leading role” in the eight years of negotiations leading up to the agreement, but he and related Chinese commentary also stressed China’s overall importance in this pact, including nations with about 30% of the world’s population and 30% of the world’s GDP. Alluding to the United States in referring repeatedly to the negative consequence of “unilateralism and protectionism,” Chinese officials stressed the importance of Chinese trade with RCEP countries, which amounted to $1.06 trillion in the first three quarters of 2020, representing one-third of Chinese foreign trade. Chinese officials also used the momentum from the RCEP deal to encourage forward movement in Chinese efforts to improve trade relations with the other “Plus 3” countries, Japan and South Korea.

Chinese commentators at this time also emphasized the importance of stabilizing and reviving regional “supply chains” among China and its regional and global trading partners. The two main sources of disruption were the COVID 19 pandemic and what were seen as “coercive efforts” and “bribing” by the United States to remove China from global supply chains.

Other themes included Li’s emphasis on China’s role in regional efforts to counter the COVID-19 pandemic. He told the annual meeting of the ASEAN Plus 3 countries that China stands ready to engage in international cooperation on vaccines “with all parties” and promote the construction of an ASEAN Plus 3 emergency reserve center for medical materials. Supporting Chinese commentary highlighted China’s continued provision of protective equipment, medical devices, and vaccines to ASEAN and other countries. Li was optimistic that success in pandemic recovery would prompt advances in Chinese and regional economic growth, making East Asia the only region of the world to achieve economic growth in 2020.

Chinese interaction with the South China Sea during the regional meetings included Li’s presentation at the EAS which repeated Chinese pledges to “uphold” the rule of law and work with ASEAN countries to achieve a Code of Conduct in the South China Sea “at an early date.” At the ASEAN-China leaders meeting Li added that the situation in the South China Sea “is stable in general.”

Xi Jinping at APEC, China-ASEAN Expo

Figure 3 Xi Jinping speaks during the annual Central Economic Work Conference in Beijing. The annual Central Economic Work Conference was held in Beijing from Dec 16 to 18. Photo: Xinhua

Building on the momentum of the RCEP agreement reached on Nov. 15, Chinese President Xi Jinping at the APEC leaders meeting on Nov. 20 capped his emphasis on multilateralism, an open world economy, and the leading role of the World Trade Organization with the announcement that China “will give favorable consideration to joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTTP).” That accord is a Japan-led effort to move forward with the high-standard Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) after US withdrawal from the TPP. During the Obama administration, the United States, Japan, and other TPP partners viewed the TPP as a means to get China to curb its widespread economic practices undermining free trade so it could join the TPP. Japanese Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide’s presentation at APEC on Nov. 20 said Japan was open to expanding CPTPP membership, leading ultimately to a much broader “Free Trade Area of the Asia Pacific,” long endorsed by APEC. Initial reaction to Xi’s interest in joining the CPTPP was mixed, with some prominent Japanese commentators warning of suspected Chinese efforts to use CPTPP membership to undermine its high standards and reinforce Beijing’s economic practices adverse to Japan and other CPTTP members.

A week later, Xi broke with past practice of lower-level Chinese officials’ addressing the annual China-ASEAN Expo and China-ASEAN Business and Investment Summit. His speech to the participants advanced China’s newly prominent view of the China-ASEAN relationship as “the most successful and vibrant model of cooperation in the Asia-Pacific” in accord with Beijing’s platitudinous “community with a shared future for mankind.” Xi highlighted Chinese support for supplying high-technology goods involved with smart city, 5G, artificial intelligence, e-commerce, big data, blockchain, and telemedicine. He said China would meet ASEAN needs for COVID-19 vaccines and offer financial support for the COVID-19 ASEAN Response Fund. He pledged to train 1,000 health personnel from ASEAN countries and to assist ASEAN in developing a regional reserve of medical supplies for public health. Xi advised that China’s rapid economic rebound from the pandemic will fuel the worldwide recovery and ASEAN countries and others around the world will benefit.

As usual, Chinese publicity outlets followed the leader’s pronouncements with glowing supporting accounts, in this instance focused on advances in China-ASEAN relations from the “golden era” of the current decade to the coming “diamond decade” of positive relations. They averred that the improvement has been based on three key elements: public health cooperation, economic development, and building mutual trust. Notably, ASEAN in 2020 overtook the European Union as China’s largest trading partner, with a value of $575.76 billion in the first 10 months of 2020, up 7% from the previous year. China’s direct investment in ASEAN markets grew by 75% over the past year to $10.72 billion. Big ticket infrastructure projects going forward include the China-Laos railway and Indonesia’s Jakarta-Bandung high speed railway. Mutual trust was said to be built on China-ASEAN intergovernmental mechanisms to manage South China Sea disputes, including the efforts to develop a Code of Conduct. Also, Southeast Asian counties were seen as refusing to join US efforts to counter Chinese ambitions in the South China Sea and elsewhere in the region.

Dealing with the US and Related Challenges

While praising progress in China’s growing role in regional integration, Beijing remained on guard against US challenges, as well as those by allies and partners supported by the United States. Foreign Minister Wang Yi speaking at the East Asia Summit foreign ministers’ meeting on Sept. 9 cited recent US military exercises in the South China Sea to argue that the United States is the main driver of militarization and the most dangerous threat to peace in the region. Continuing to challenge Chinese behavior in the South China Sea, US Secretary of State Pompeo attacked Chinese “bullying” and pledged US support for regional disputants against China while speaking to an ASEAN-US ministerial meeting the next day.

To shore up Chinese relations with Southeast Asian countries in the face of US charges, in September China’s most senior foreign policy official, Politburo Member Yang Jiechi, visited Myanmar to solidify close relations. China’s Defense Minister Wei Fenghe also visited Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei, and the Philippines. In October, Wang Yi traveled to Cambodia, Malaysia, Laos, Thailand, and Singapore, while also having talks with a senior Indonesia envoy in China and with the Philippines foreign minister visiting China, the latter of which official Chinese media said were efforts to counter US attempts to “drive a wedge” between China and ASEAN states over the South China Sea and other issues. Chinese media criticized Pompeo’s visits to Indonesia and Vietnam in October, and National Security Adviser O’Brien’s visits to Vietnam and the Philippines in November.

Meanwhile, Indonesia in September issued a foreign ministry protest and sent a patrol ship to confront a Chinese Coast Guard ship in Indonesian-claimed waters. In November, the CSIS Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) showed a Chinese Coast Guard ship engaged in another episode of intimidating Malaysia from engaging in drilling in waters coming within China’s broad South China Sea claim. AMTI also provided a yearend review showing that aggressive patrolling and harassment by Chinese Coast Guard ships in the South China Sea was at the same level in 2020 as in 2019. The list of countries submitting diplomatic notes to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf challenging China’s South China Sea claim grew when France, Germany, and the United Kingdom submitted a joint note in September challenging China’s claims and endorsing the findings of the UNCLOS Arbitral Tribunal of July 2016.

Chinese sensitivity to US regional challenges grew with the upgrade of the US-backed Lower Mekong Initiative to the Mekong-US Partnership in September. The partnership provides funded support for Mekong countries that compete with Chinese advances, including under the Belt and Road Initiative. Adding to the challenge is US criticism of China for blocking the flow of the river and causing widespread drought among Mekong countries. While sharply criticizing US intervention, Beijing has recently shown more openness in sharing water information with downstream countries.

Australian-China Acrimony Amid Punitive Trade Restrictions

Unprecedented decline in Australian-Chinese relations on account of acute differences over Chinese manipulation of Australian domestic affairs, expansionism in the South China Sea, malfeasance in China’s initial handling of the coronavirus, and repression in Hong Kong and Xinjiang (as explained in the previous edition of Comparative Connections) continued in this reporting period. Chinese behavior graphically demonstrated to Australia, its ally in Washington, and its partners throughout Southeast Asia and the wider region the uniquely strong capacity of the Chinese Communist Party/State to counter opponents by exploiting their economic and other dependence. Notably, Beijing mobilized government and party mechanisms to carry out a wide-ranging series of abrupt trade restrictions along with cutbacks in investment, tourism, and student exchange to apply pressure to the Australian government and constituencies which rely heavily on economic and other exchanges with China. The show of force added to the growing record of heightened determination by strongman Xi and the Chinese party/state, more than any other major power in living memory, to develop the economic and related dependence of others on it to use as leverage, assuring deference to Chinese demands. Beijing’s mobilization of government and party channels resulted in trade and other restrictions that were often nontransparent and difficult to counter using existing international mechanisms. And Chinese rhetoric all the while sought to shore up Beijing’s avowed commitment to free trade and noninterference in other countries’ internal affairs, now viewed with increasing cynicism in Australia and elsewhere.

Despite some seemingly moderate Chinese rhetoric in October urging Australia to change course in its criticism of Chinese actions in Australia and abroad, Chinese restrictions on trade involving purchases of Australian wine, lobsters, copper, sugar, cotton, timber, and coal took effect in early November. What China was demanding to restore normal trade became clear in mid-November when Chinese officials met with Australian media and provided a list of 14 grievances that Australia needed to remedy. Widespread public outrage in Australia followed the Twitter post of a controversial Chinese foreign ministry spokesman, known for his aggressive, so-called “wolf-warrior” manner, showing the fabricated image of an Australian soldier with a knife to the throat of an Afghan child. Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison denounced the “disgusting slur” and his government demanded an apology. Beijing was unapologetic, with official commentary in December advising that, from a Chinese perspective, the current Australian government is no longer trustworthy and Chinese people no longer see Australia as a friendly country, an attractive tourist destination, or a reliable destination for overseas studies. It forecast continued tensions.

Figure 4 The fake image posted on by a Chinese official on Twitter depicting an Australian soldier holding a knife to the throat of an Afghan child. Photo: Zhao Lijian/Sky News

With domestic business and other constituencies feeling the impact of Chinese punitive restrictions, Morrison at times seemed to soften his tone toward China, seeking dialogue. Nonetheless, Australia followed through with moves viewed negatively in China. As noted, it participated for the first time in the US-India-Japan Malabar naval exercises in November. That month it also established a far-reaching defense cooperation pact with Japan, a strategic partnership action plan with Vietnam, and a strategic partnership with Thailand.

Philippines’ Mixed Signals about China

The ambivalence in the Philippines government’s approach to China over the South China Sea disputes amid an acute US-China rivalry in the region, seen earlier this year, continued in the current reporting period. On the one hand President Rodrigo Duterte, in a message to the UN General Assembly in September, gave his strongest defense yet of the 2016 UNCLOS arbitration tribunal ruling in favor of the Philippines and against China’s expansive South China Sea claims. And despite his anti-US leanings, Duterte had earlier suspended a decision to abrogate the Visiting Forces Agreement with the United States. That suspension was continued in November, winning praise from visiting National Security Advisor Robert O’Brien. O’Brien came to the Philippines for a ceremony marking the transfer of $18 million of precision-guided missiles and bombs and other advanced weapons that President Trump had promised in a phone call to Duterte in March. Duterte reportedly advised Philippine-Americans to vote for Trump in the 2020 US election. O’Brien strongly affirmed the recent US commitment to support Philippine forces and interests against Chinese attack in the South China Sea, stating “any armed attack on the Philippines forces aircraft or public vessels in the South China Sea will trigger our mutual defense obligations.” Against the background of such stepped-up US support, Foreign Minister Teodoro Locsin said in September that the Philippines won’t follow China’s policy of keeping the US out of the South China Sea.

On the other hand, visiting Chinese Defense Minister Wei Fenghe was welcomed in Manila in September, bringing a $19 million grant of equipment for humanitarian assistance and disaster relief. Both sides agreed to seek ways to sustain stability in the disputed South China Sea. The Chinese foreign minister met with Locsin in China as part of his interchange with several Southeast Asian counterparts in October. They muted public differences, while engaging in what were called “candid and in-depth exchanges.”

Chinese media welcomed Duterte’s decision not to follow US sanctions imposed on China Communications Construction Company because of its involvement in construction of artificial islands in the disputed South China Sea. The firm is currently involved in major Philippines infrastructure projects.

Duterte’s decision announced on Oct. 15 to lift a six-year ban and allow oil exploration to resume in Philippines-claimed areas in the South China Sea also claimed by China was subject to different interpretations. Attention focused on a Philippines-China memorandum on joint development signed in 2018 but not yet enacted involving a Philippine oil company and a Chinese oil company. Two days after the announced lifting of the ban, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijan said, “China hoped it could work together with the Philippines in jointly developing energy projects in the South China Sea.” He revealed that “China and the Philippines have reached consensus on the joint development of oil and gas resources in the disputed waters and have established a cooperation mechanism or relevant consultation.”

Experts disagreed on the significance of these developments. Some were optimistic that arrangements could lead to survey and drilling with both companies sharing production. One interpretation was that the Chinese company could become involved in oil exploration under a service contract with the Philippines company licensed by the Philippine government. The arrangement was not seen to undermine Philippines’ jurisdiction over resources in its Exclusive Economic Zone nor did it involve China conceding its sovereignty claims. But others judged that China’s agreeing to such terms in contested waters would represent an unlikely reversal of Chinese practice.

Indonesia Cautions China and the United States

Indonesia’s Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi cautioned the United States and China in early September not to entangle Jakarta in their regional struggle for influence. In an interview with Reuters, she emphasized that “ASEAN, Indonesia, wants to show to all that we are ready to be a partner. We don’t want to get trapped by this rivalry.” The message was a shot across the bow to both Washington and Beijing following increasing levels of hostile rhetoric, diplomatic, and military maneuvers in the South China Sea.

In October, Indonesia reinforced its message of neutrality when President Joko Widodo publicly rejected a proposal earlier in 2020 by Washington to allow US P-8 Poseidon maritime surveillance planes to land and refuel in Indonesia. The P-8 plays a role in monitoring China’s military activities in the South China Sea. The US proposition surprised Indonesian officials given Jakarta’s longstanding policy of never allowing foreign militaries to operate there. Observers noted that the US request was seen as “out of place” and “an example of clumsy over-reach.”

Outlook

Probably the most important change impacting China-Southeast Asia relations in 2021 will be the inauguration of Joseph Biden as the 46th president of the United States. Few observers on either side of the Pacific are optimistic about a major breakthrough in the strong China-US rivalry in Southeast Asia or elsewhere in the world. The new US president is likely to remain preoccupied with domestic priorities for many months. He is widely viewed as a much more predictable leader who places a much higher value on allies and partners than President Trump. China has been publicly cautious in dealing with the incoming leader, willing to engage in dialogue but offering no changes or concessions in the face of widespread US complaints.

Sept. 1, 2020: Thailand announces delay of a $724 million submarine deal with China after public outrage over the deal amid the backdrop of a flagging Thai economy due to the global pandemic.

Sept. 8, 2020: Indonesian Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi cautions the United States and China not to entangle Jakarta in their regional struggle for influence.

Sept. 9, 2020: Foreign Minister Wang Yi criticizes the United States when speaking at an East Asia Summit foreign ministers’ meeting.

Sept. 10, 2020: Secretary of State Pompeo, speaking to an ASEAN-US Ministerial meeting, attacks Chinese “bullying” and pledges US support for regional disputants against China.

Sept. 24-29, 2020: Chinese military forces carry out exercises simultaneously in the South China Sea and three other locations along the Chinese coast.

Oct. 15, 2020: Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte lifts a moratorium on oil and gas exploration in waters claimed by China and the Philippines. The step is viewed by some experts as opening the way to joint survey and drilling by a Chinese company working with a Philippines company with both companies sharing the production. Other experts are skeptical.

Nov. 3-6, 17-20, 2020: Annual Malabar naval exercises take place in two stages in different parts of the Indian Ocean. They involve forces from India, the United States, Japan, and for the first time Australia.

Nov. 13, 2020: Prime Minister Li Keqiang speaks at annual ASEAN Business and Investment Summit.

Nov. 15, 2020: Li and government leaders from 14 other Asian-Pacific states sign the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (RCEP).

Nov. 20, 2020: Chinese President Xi Jinping addresses the 27th Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Economic Leaders Meeting.

Nov. 27, 2020: Xi addresses 17th China-ASEAN Expo and China-ASEAN Business and Investment Summit.

Nov. 30, 2020: Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison denounces a Twitter post by a Chinese foreign ministry spokesman showing the fabricated image of an Australian soldier with a knife to the throat of an Afghan child.

Dec. 21, 2020: China’s navy announces that the carrier Shandong and supporting warships passed through the Taiwan Strait to participate in “normal” exercises in the South China Sea.