Articles

As the Ukraine conflict was poised to expand, the “extremely complicated” situation at the frontline (in Vladimir Putin’s words on Dec. 20) gave rise to intensified high-level exchanges between Moscow and Beijing as they searched for both an alternative to the conflict, and stable and growing bilateral ties. As the Ukraine war dragged on and mustered a nuclear shadow, it remained to be seen how the world would avoid what Henry Kissinger defined as a “1916 moment,” or a missed peace with dire consequences for not only the warring parties but all of civilization.

Putin and Xi in Samarkand

High-level exchanges regained momentum in the last few months of 2022 as Chinese leader Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin met on the sidelines of the SCO annual summit in Uzbekistan on Sept. 15. A week before, top Chinese legislator Li Zhanshu paid an official visit to Russia, starting in Vladivostok where he met Putin during Russia’s 7th Eastern Economic Forum. By yearend, Dmitry Medvedev, former Russian president (2008-2012) and now chairman of the United Russia party, paid a surprise visit to Beijing, which was followed by a video conference between Xi and Putin on Dec. 30.

The Putin-Xi September meeting in Uzbekistan was the first in-person gathering since they met in Beijing in late February, shortly before the Ukraine war. Prior to this, they had only a virtual meeting on June 15. In the ancient Uzbek city of Samarkand, the two leaders reportedly exchanged views on a wide range of global, regional, and bilateral issues. Both praised the current friendly relationship between their two countries and vowed to continue to work together for global and regional stability.

The Putin-Xi meeting took place against a backdrop of a “rapidly changing world” (Putin), and “formidable global changes that have never been seen in history” (Xi). In Ukraine, conflict had turned from a World War II-style blitzkrieg to one of World War I-style attrition. Meanwhile, Washington’s massive and sustained assistance to Ukraine paralleled rising US-China confrontations, particularly over Taiwan. For many in China, the specter of Taiwan turning into another Ukraine was no longer a distant possibility, no matter how hard China tried to differentiate the Taiwan issue from that in Ukraine while maintaining its principled neutrality posture between Moscow and Kyiv.

Putin apparently understood China’s dilemma. While calling his Chinese counterpart a “dear comrade” (Уважаемый товарищ), a common usage during the Sino-Soviet “honeymoon” (1949-59), Putin expressed gratitude for China’s “balanced position in connection with the Ukraine crisis,” saying that “we understand your questions and your concerns in this regard,” and that “we will certainly explain in detail our position on this issue.” As for the Taiwan issue, Putin reiterated that “we have firmly, in practice, abided by the one-China principle.”

Xi thanked Putin for Russia’s consistent one-China stance. Xi did not mention Ukraine in his opening remarks. Instead, he stressed the need to enhance strategic and practical coordination with Russia, particularly regarding the function of the SCO.

SCO: Out of Covid and into the Shadow of the Ukraine War

The 22nd summit of the SCO was held in Samarkand, Uzbekistan following the Xi-Putin mini-summit. It was the first since Russia’s “special military operation” in February. The pandemic, too, had until this point prevented any normal gathering of the SCO leaders.

All SCO member states (except Russia), as well as the SCO itself, adopted a neutral stand regarding the Ukraine war, as was the case in the 2008 Georgian-Russian war. They did not want to choose between the West and Russia. Nevertheless, the SCO would have to deal with the disruptive effect of the Ukraine war as global and regional economies were already strained by the pandemic.

In Samarkand, the SCO heads of state approved a five-year plan (2023-2027) for implementation of the “Treaty on Long-term Neighborliness, Friendship and Cooperation of the SCO Member States,” signed 15 years before. They also inked a series of documents covering climate change, transportation, finance, supply chains, energy, food security, etc.

A considerable part of Putin’s speeches at the summit explained “the current complicated international situation” and Russia’s responses. He was particularly critical of Western sanctions against Russia, including EU’s “selfish behavior” regarding Russia’s exports of grain and fertilizers. Beyond that, the Russian president was upbeat about SCO achievements.

Samarkand was Xi’s first foreign trip since January 2020. He seemed more concerned about SCO security and its effective governance to offset “color revolutions.” In this regard, a balanced, effective, and sustainable security architecture was needed to deal with traditional and nontraditional security including data, bio-, and outer space security. Xi offered to train 2,000 law enforcement personnel of SCO member states in the next five years. In post-Afghan Central Asia and with Moscow’s preoccupation with the Ukraine war, Beijing was apparently willing to do more to secure its huge investment in the region’s sprawling energy and transit infrastructure.

Until recently, the SCO had been slow to accept new members whose accession to full status usually went through lengthy procedures. In Samarkand, Iran finally signed a memorandum of obligations for full membership status 17 years after becoming an observer of the SCO. Meanwhile, the summit added five additional “dialogue partners” (Bahrain, Kuwait, Maldives, Myanmar, and the United Arab Emirates). A year before, Armenia, Egypt, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia joined the observer group.

In Samarkand, Putin pushed, particularly, for Belarusian membership. “We have always advocated that Belarus, which is Russia’s strategic partner and closest ally, should participate fully in the SCO. This will undoubtedly improve our ability to advance unity in politics, the economy, security, and humanitarian matters,” stated Putin. Now after 12 years as a “dialogue partner” and 10 years as an “observer,” Belarus was on track for full membership.

SCO was far from perfect for current and potential members, but a bigger and more complex body could be guaranteed to be less efficient. In retrospect, the SCO has created an environment in which its founding members were willing and able to negotiate and compromise with one another on vital interests such as border delineation and security in a fluid, sometimes chaotic post-Soviet space. In contrast to the post-Soviet space in Europe, much of Central Eurasia, including the long Sino-Russia border region, avoided the worst of populism and extreme nationalism. Now in an increasingly volatile and divided world, the SCO became more attractive for those who looked for stability and certainty.

Tales of Two “Surprise” Diplomacies

For Carl von Clausewitz, war should never be severed from politics, but is a mere continuation of policy “by other means.” By the end of 2022, the warring parties of the Ukraine conflict were heading out of Europe, albeit in different directions. On Dec. 21, Deputy Chairman of the Russian Security Council Dmitry Medvedev traveled to Beijing. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy headed for Washington.

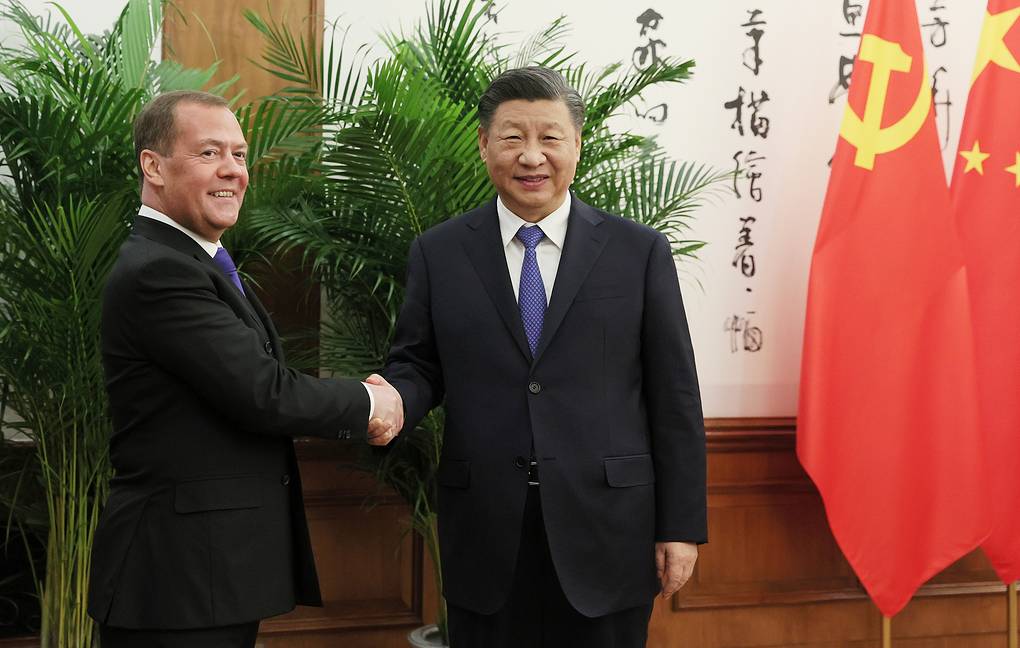

Medvedev’s “surprise visit” to Beijing was made in his capacity of chairman of Russia’s United Party and at the CPC’s invitation. Via this “unique” party-to-party channel for high-level communication, the former Russian president delivered a message from Putin. A statement released by Medvedev’s office provided only sketches of the Beijing talks, indicating that the meeting covered a broad range of issues, including those of “the post-Soviet region… and the Ukrainian crisis.” The Chinese media, in both English and Chinese versions, added details, including Xi’s reiteration of China’s long-standing position of “objectivity and fairness,” and that China “actively promotes peace talks.”

According to the Chinese readout, Medvedev echoed Xi’s “peace” point by saying that “Russia is willing to solve the problems through peace talks.” The crisis, however, was “very complicated,” implying that the 10-month war may become protracted before winding down. Given this, Xi urged all “relevant parties” to “remain rational and exercise restraint,” indicating China’s concerns over possible escalation and spillover to other countries.

Figure 1 Russian Security Council Deputy Chairman Dmitry Medvedev and Chinese President Xi Jinping. Photo: Yekaterina Shtukina/POOL/TASS

Medvedev was well-known in China thanks to his four-year presidency of the Russian Federation. It was unclear if his surprise visit was a coincidence with Zelenskyy’s “surprise” US trip. It occurred nonetheless as Russia’s strategic environment continued to deteriorate as Putin approved a Russian military plan for a significant resizing (from 1 million to 1.5 million) and re-structuring (re-establishing the Moscow and Leningrad Military Districts, etc.). Obviously, Russia’s partial mobilization (300,000) on Sept. 21, the first since the end of the Soviet Union, fell short of expectations. On Dec. 26 and 29 Russia’s strategic airbase Engels was bombed by Ukraine drones, following an initial attack on Dec. 5. Ukraine’s military capability apparently was not weakened after two months of Russian retaliatory bombing of Ukraine’s power infrastructure following the Oct. 8 Crimea bridge bombing. Some Chinese observers noticed that the distance between the Ukraine city Kharkiv and Russia’s Engles air base was about 687 km, similar to that between Kharkiv and Moscow. This means Ukraine had acquired the capability to strike Moscow if it chose to do so. If that happened, escalation was guaranteed.

Figure 2 US President Joe Biden welcomes Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy at the White House in Washington on Dec. 21, 2022. Photo: AP Photo

Despite their opposite travel directions, the outcomes of Zelenskyy and Medvedev’s diplomacy with the world’s two largest powers were almost pre-determined. Even before his arrival in Washington, the US House proposed $45 billion in emergency funds for Ukraine, totaling $110 billion by year’s end. Once in town, the Ukraine president received a hero’s welcome as a 21st-century Winston Churchill while obtaining $1.8 billion in military assistance, including a Patriot missile battery.

The specifics of Putin’s letter to Xi remained undisclosed. The outcome of Medvedev’s trip to Beijing was, too, predetermined regarding the Ukraine war. Because of its position of neutrality (or “impartial” and “just” according to Beijing), the only thing China could do was to help Russia search for a peaceful ending to the conflict. Upon returning home, Medvedev reportedly said that the Beijing talks were “fruitful,” or “meaningful” (содержательной) according to Putin when he was conversing with President Xi via video nine days later.

Putin-Xi New Year’s Eve Meeting (Online)

Unlike the casual exchange of New Year greetings that occurred for many years, the Putin-Xi video meeting this time was substantive and with a visible element of urgency, particularly from the Russian side, given rapidly unfolding events (Zelenskyy’s US trip). A significant part of Putin’s opening remarks was about Russia’s energy export to China. “Russia holds second place in terms of pipeline gas supplies to China, and fourth in terms of LNG exports,” said Putin, implying potential for future growth, particularly in the wake of the Nord 1 & 2 destruction in late September and the EU cap on Russian oil prices set in early December.

Defense and military technology cooperation was also discussed between the two leaders, according to the Kremlin readout. It “has a special place in the entire range of Russian-Chinese cooperation and our relations. We aim to strengthen cooperation between the armed forces of Russia and China,” said the Russian president.

As to Russia-China coordination in diplomacy in facing “unprecedented pressure and provocations from the West,” Putin reminded his Chinese counterpart that Moscow and Beijing “defend our principled positions and protect not only our own interests, but also the interests of all those who stand for a truly democratic world order and the right of countries to freely determine their destiny.”

Given the stakes for Russia-China relations, Putin pointedly reminded his Chinese counterpart of the need for a state visit to Moscow in early 2023: “I have no doubt that we will find an opportunity to meet in person…next spring with a state visit to Moscow. This will demonstrate to the whole world how strong the Russian-Chinese friendship is, our agreement on key issues. Your visit will become the main political event of the year in bilateral relations.”

In his brief opening remarks, Xi did not echo Putin’s invitation for a trip to Moscow in the coming months. Under normal circumstances, Xi is supposed to be in Moscow in early 2023 to reciprocate Putin’s February 2022 Beijing trip (as both a state visit and joining the opening of the Beijing Winter Olympics).

Still, Xi spoke highly of relations with Russia and the “need to maintain close coordination and collaboration in international affairs.” He did not touch mil-mil cooperation but called for good use of “existing working mechanisms” for more “practical cooperation” in the economic area.

The Chinese readout concluded with Xi’s call for peace dialogue and China’s impartial posture regarding the Ukraine conflict. Apparently aware of the enormous difficulties on the part of Russia in reaching a peaceful settlement, Xi stated that “[T]he path of peace talks will not be a smooth one, but as long as parties do not give up, there will always be prospect for peace.” To drive his point home, Xi “stressed that China has noted Russia’s statement that it has never refused to resolve the conflict through diplomatic negotiations and China commends that.”

The Kremlin transcript skipped Xi’s peace points. It is unclear how Xi’s state visit would be affected by the war and prospects for peace talks. In this regard, China found itself between a rock and hard place. At a minimum, a visit to Russia without a ceasefire would be politically inconvenient given China’s declared impartiality. At the strategic level, however, skipping a state visit to Russia would undermine the mutual trust between China and its embattled partner, whose support for China is vital as Beijing’s relations with Washington remained strained and even potentially explosive over Taiwan.

In late December, the same $1.65 trillion US government spending package that authorized $45 billion for Ukraine also allocated $2 billion for Taiwan’s defense, the first installment of a $10 billion package for Taiwan in 2023-2027. In a parallel move, Taiwan was to extend its compulsory military service from four months to a year starting in 2024. Meanwhile, Japan was acquiring offensive weapons (500 US-made long-range Tomahawk cruise missiles) with a 26.8% increase in defense spending to 82 trillion yen ($51.4 billion) for the 2023-24 fiscal year. Given these ominous signs, Beijing chose to continue its “normal” relations with its only reliable partner (Russia) in East Asia.

Normal Relations in Abnormal Times

In the last few months of 2022, both Moscow and Beijing seemed more determined to maintain a “normal” strategic partnership in the midst of fluidity and growing challenges. On Sept. 19, the 17th round of China-Russia strategic security consultation was held in Fujian Province, which faces Taiwan. Co-chaired by senior security officials (Yang Jiechi and Nikolai Patrushev), the consultation reportedly “achieved positive results.” Patrushev took “a firm stand on the one-China principle, and firmly supports the measures taken by the Chinese government to safeguard the sovereignty and territorial integrity on the Taiwan question.”

The Yang-Patrushev consultation was held four days after the Xi-Putin meeting in Uzbekistan and was followed by intensive engagement in diplomatic and security areas. Foreign Minister Wang Yi and Russian counterpart Lavrov met multiple times: a meeting in New York on Sept. 21, telephone talks on Oct. 27, and on the sidelines of the G20 meeting in Indonesia on Nov. 15. Even the change of the Russian ambassador in Beijing was given unusually high attention. In his meeting with outgoing Russian Ambassador Andrey Denisov on Sept. 3, Foreign Minister Wang Yi described Denisov as China’s “good friend, old friend, and genuine friend.” Russia’s Ambassador to China Igor Morgulov, too, was given prominent reception.

A consistent theme of these activities was the Ukraine conflict and its possible de-escalation and resolution. In his New York meeting with Lavrov, Wang reiterated that China would continue upholding an objective and just position to promote peace talks. In an emergency UN session on Ukraine on Oct. 12, Chinese Ambassador Geng Shuang presented a four-point proposal urging all sides not to abandon dialogue and avoid the escalation and spillover effect of the Ukraine war. In their Nov. 15 meeting on the sidelines of the G20summit in Bali of Indonesia, Wang told Lavrov that “China noticed” Russia’s Nov. 2 reaffirmed position that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought,” which showed Russia’s “rational and responsible attitude.”

Russia and China also markedly increased interactions in the security arena with a series of drills and joint patrols in the last few months of 2022:

- Sept. 1-7: 2,000 PLA servicemen, 300 vehicles, 21 aircraft and 3 warships joined Russia’s Vostok-2022 military drill in the Far East. For the first time, Chinese fighter-bombers (J-10B) took off from China and dropped payloads on targets inside Russia.

- Sept. 15: Russian and Chinese navies launched their 2nd joint Pacific patrol. They reached Alaskan waters on Sept. 19.

- Nov. 30: Russian and Chinese strategic bombers conducted a joint patrol over the western Pacific. Four Russian Tu-95 and two Chinese H-6K bombers flew over the Sea of Japan and the East China Sea during an eight-hour mission, the 5th time since 2019, and the second time in 2022. As part of the drills, Russian bombers for the first time landed in China and Chinese bombers flew to an air base in Russia.

- Dec. 21-27: Russian and Chinese navies conducted Joint Sea-2022 naval exercises in the East China Sea, just 300 km from Taiwan, which was the closest to the island in the Sino-Russian joint naval exercises. Four Russian warships joined five Chinese vessels and practiced various items. It was the 10th drill of this kind since 2012.

Much of these drills was “routine.” With the Ukraine conflict and rising tension over Taiwan, these exercises assumed an additional sense of importance and urgency, however.

Figure 3 The routes of the Power of Siberia pipeline (left), the Sakhalin–Khabarovsk–Vladivostok pipeline (right) and the proposed link between them (center). Photo: Power of Siberia

Even economics, the traditional “weakest link,” showed signs of progress. The Russian side was more eager to push for more. On Dec. 21, the day Medvedev traveled to Beijing, Russia inaugurated the gigantic Kovykta gas field and the 800-km Kovykta–Chayanda section of the Power of Siberia gas pipeline. It meant a substantial increase of Russian gas exports to China in coming years through both the existing Power of the Siberia line and the proposed Mongolian route, which is part of the China-Russia-Mongolia economic corridor, now in its planning stage.

In 2022, Sino-Russian trade increased about 25%. The opening of the Blagoveshchensk-Heihe highway bridge on June 10 and the Nizhneleninskoye-Tongjiang railway bridge across the Amur River on Nov. 16 would further facilitate Russian-China economic transactions.

There are still many bottlenecks in Russia-China economic relations, particularly low efficiency and corruption on the Russian side. Western sanctions, too, were creating additional obstacles for joint projects with third-party components, such as the long-range, wide-body 280-seat passenger airliner CR929. Russia’s reluctant pivot to the east and China’s forced delinking of high-tech sectors from the West, however, gave rise to ambitious brainstorming for economic cooperation. One idea was a package of 79 large investment projects worth $160 billion in Russia’s Far East, which was discussed in the 27th prime ministerial meeting on Dec. 5.

It remains to be seen how these projects will be negotiated and initiated. By the end of 2022, Russia and China inked an agreement on a joint scientific lunar station. Construction of the lunar station was expected to be completed by 2035. Two missions were planned in 2026-2030 to test the technologies of landing and cargo delivery and the transportation of lunar soil samples to earth. Plans also included developing infrastructure in orbit and on the moon’s surface (communications gears, electric power, research, and other equipment, etc.) in 2031-2035.

Shadow of 1916

Eight years ago at the height of the Ukraine/Crimea crisis, Henry Kissinger noticed an eerily familiar fascination among the public: everybody talked about confrontation, and nobody cared about how it ended. The worry of the geo-strategist—who will be a centenarian in May 2023—was derived from his own observation of post-WWII US military operations abroad: “four wars that began with great enthusiasm and public support, all of which we did not know how to end and from three of which we withdrew unilaterally.” Kissinger advised that “the test of policy is how it ends, not how it begins.”

Fast forward to Dec. 17, 2022. In an op-ed titled “How to Avoid Another World War,” Kissinger targeted an audience now in the middle of what Kissinger saw as a comparable moment in 1916 when warring parties were briefly toying with the prospect of ending the two-year carnage inflicted by technology they “insufficiently” understood. Ultimately, those “sleepwalking” European leaders missed the chance for a formal peace process because of pride and hesitation. While “diplomacy became the road less traveled,” the war went on for two more years and claimed millions more victims.

To avoid a replay of the missed peace and WWIII in which AI weapons would assume a life of their own, Kissinger proposed a ceasefire line along the borders that existed when the war started on Feb. 24, 2022 while the territory Russia occupied prior to that—including Crimea—would be the subject of a future negotiation. Eventually, a new strategic architecture in Europe would be built in which Ukraine “should be linked to NATO” while Russia would “eventually find a place in such an order.”

Kissinger’s latest, if not last, effort to search for an end of violence in Ukraine was not an isolated endeavor. Before the Ukraine military retook Kherson on Nov. 11, Gen. Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, had pushed for a diplomatic solution as fighting headed toward a winter lull. “When there’s an opportunity to negotiate, when peace can be achieved, seize it. Seize the moment,” Milley reportedly said at the Economic Club of New York. Milley was not urging a Ukrainian capitulation but was afraid that a prolonged war would lead to more death and destruction without changing the front lines. Although senior members of the Biden administration did not share Milley’s ideas, some of them (e.g., Sullivan) had reportedly been urging Ukraine to leave space for a diplomatic opening with Russia. The Biden team was yet to find a balance between values and interests.

Kissinger’s ceasefire proposal was rejected by Kyiv. In fact, Zelenskyy signed a decree in early Oct. ruling out negotiations with Putin. In his meeting with Biden in Washington on Dec. 21, Zelenskyy reportedly rejected Biden’s framing of a “just peace” in favor of his own peace plan for a “global peace summit” by the UN in February 2023, in which Russia could only be invited if it faced a war crimes tribunal first.

Moscow appeared more receptive to Kissinger’s outline. Kremlin spokesman Peskov said Putin was “eager to give the article a thorough reading,” but “hasn’t had a chance to do so yet, unfortunately.” Putin ordered a 36-hour ceasefire in Ukraine for the Orthodox Christmas holiday (Jan. 7, 2023).

Russia’s inclination to pause the conflict was perhaps genuine, as the impact of the seemingly limited “special military operation” was felt “far bigger than that of the Crimean War of the mid-19th century or the Russo-Japanese war of the beginning of the 20th century,” according to Dmitry Trenin. “The closest analogy one can find in Russian history is the First World War, and not only due to the dominance of artillery and the reality of trench warfare,” added the Russian geostrategist. Trenin was not fatalistic but realistic enough to conclude his provocative piece that “[T]he path to a better future for Russia will have to be created in Ukraine—undoubtedly at a high price.”

Beijing closely followed the interaction of various peace/ceasefire proposals while maintaining steadfastly its own peace-oriented posture. This was the case for all in-person and video meetings between top leaders (Xi, Putin, and Medvedev) and senior diplomats. Ukraine was not neglected. In his meeting with Ukraine Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly in New York on Sept. 22, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi said that China was for peace and by peace regarding the Ukraine conflict, and “never stands idly by, never adds fuel to the fire, and never takes advantage of the situation for self-interests.” Kuleba reportedly replied that Ukraine attached importance to the international status and important influence of China, and expected the Chinese side to play an important role in alleviating the current crisis [underline added by writer]. Wang apparently urged Ukraine to move toward a negotiated peace/ceasefire. Kuleba responded by saying that “Ukraine is ready to conduct dialogue and negotiations serving its national interests.” During the meeting, Kuleba reiterated that Ukraine was committed to the one-China policy and expected to strengthen exchanges and cooperation with China in various fields.

Figure 4 Wang Yi Meets with Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba of Ukraine. Photo: Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs

For Beijing, peaceful resolution of the Ukraine crisis had additional urgency because of its adverse impact on relations with Washington. Despite China’s principled neutrality, there was a growing conceptual “Ukraine-Russian trap” (俄乌陷阱) in US-China relations regarding Taiwan, argued Huang Renwei (黄仁伟), a prominent scholar in Shanghai. In this 21st-century “prisoner’s dilemma” game, Beijing worried about a US-induced Ukrainization of the Taiwan issue that would interrupt China’s historical rejuvenation; meanwhile, Washington saw a likely Russian-style operation against Taiwan by the Mainland. This “you-go-low-and-I-go-lower” race to the worst scenario would intensify confrontation between the two largest powers with grave consequences. Beijing’s insistence on a peaceful resolution of the Ukraine crisis, therefore, was increasingly assuming a geopolitical dimension.

As the Ukraine conflict dragged on, Kissinger’s 1916 analogy was particularly relevant in the case of nuclear weapons. The year 2022 started with a Joint Statement by five nuclear-weapon states on preventing nuclear war and avoiding arms races. It was, ironically, followed by a proliferation of nuke talks from all sides, something that was not seen even at the height of the Cold War. Russia’s seizure of Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant and its off-and-on shelling, too, reinforced the nuclear specter.

Precisely because of this looming danger, the need for diplomacy was paramount, though it “may appear complicated and frustrating,” cautioned Kissinger. The alternative could be far worse. In a broader conflict with AI weapons that “already exist, capable of defining, assessing and targeting their own perceived threats and thus in a position to start their own war,” warned Kissinger, civilization may not be “preserved amid such a maelstrom of conflicting information, perceptions and destructive capabilities.”

Unlike either WWI or WWII, WWIII would leave no winners.

Sept. 1-7, 2022: Russia conducts its Vostok-2022 military drill in the Far East involving more than 50,000 troops from 13 countries, including 2,000 servicemen, 300 vehicles, 21 aircraft, and 3 warships from China. President Putin observes the drill on Sept. 6. For the first time, Chinese fighter-bombers (J-10B) take off from China and drop their payload inside Russia.

Sept. 3, 2022: Foreign Minister Wang Yi meets in Beijing with outgoing Russian Ambassador Andrey Denisov who had been in the position since 2013.

Sept. 7-10, 2022: Top legislator Li Zhanshu pays an official visit to Russia and meets President Putin in Vladivostok. He was invited by Chairman of the Russian State Duma Vyacheslav Volodin.

Sept. 12, 2022: CPC Politburo member Yang Jiechi meets in Beijing with the outgoing Russian Ambassador Andrey Denisov.

Sept. 14, 2022: Deng Li, China’s vice foreign minister on Middle Eastern affairs, holds political consultation with his Russian counterpart Mikhail Bogdanov via video link.

Sept. 15, 2022: Four Russian naval ships and three Chinese vessels launch their 2nd joint Pacific patrol. They are spottedoff the Alaska waters by US Coast Guard on Sept. 19.

Sept. 15, 2022: Xi and Putin meet in person on the sidelines of the SCO Summit in Uzbekistan.

Sept. 16, 2022: SCO holds its 22nd summit in Uzbekistan, the first in-person gathering since the pandemic. SCO expansion is one of the main issues. The 6th China-Mongolia-Russian summit is hold on the sidelines of the SCO summit. Among the observer and partner participants were Alexander Lukashenko (Belarus), Seyyed Ebrahim Raisi (Iran), Ukhnaagiin Khurelsukh (Mongolia), Ilham Aliyev (Azerbaijan), Recep Tayyip Erdogan (Türkiye) and Serdar Berdimuhamedov (Turkmenistan).

Sept. 19, 2022: 17th round of China-Russia strategic security consultation is hold in Fujian Province facing Taiwan. It is co-chaired by senior security officials (Yang Jiechi and Nikolai Patrushev). The consultation reportedly “achieved positive results.”

Sept. 21, 2022: Foreign Minister Wang Yi meets with Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) in New York.

Sept. 22, 2022: FM Wang Yi meets Ukraine Foreign Minister Kuleba on the sidelines of the UNGA. Wang briefs Kuleba on China’s “impartial and just” position on the Ukraine conflict, saying that China “never stands idly by, never adds fuel to the fire, and never takes advantage of the situation for self-interests.” Kuleba reaffirms Ukraine’s support for the one-China principle.

Sept. 24, 2022: Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov accuses the United States of “playing with fire” on the Taiwan issue in his speech at the UNGA meeting.

Sept. 27, 2022: Russia and China sign contracts for deployment of Russia’s GLONASS stations in China (Changchun, Urumqi, and Shanghai) and China’s Beidou system stations in Russia (Obninsk, Irkutsk, and Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky).

Sept. 27, 2022: President Xi Jinping sends a message of condolence to Putin over a school shooting incident in the country.

Oct. 17, 2022: Putin signs document making 2022 and 2023 Years of Russian-Chinese Cooperation in Sports and Fitness. This includes an international festival of university sports in Yekaterinburg in 2023 in which university teams from BRICS, SCO, and CIS member states will take part.

Oct. 23, 2022: Putin sends a message of greetings to President Xi on his re-election to the post of General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee.

Oct. 27, 2022: Russian FM Lavrov and Chinese FM Wang Yi hold telephone conversation. Lavrov briefs Wang on Russia’s special operation in Ukraine and thanks China for supporting Russia’s stance on Ukraine. Wang informs Lavrov about the outcomes of the CPC’s 20th congress (Oct. 16-22).

Oct. 29, 2022: President Xi sends a congratulatory message to Russia-China Friendship Association on its 65th founding anniversary.

Oct. 31, 2022: Vice Foreign Minister Ma Zhaoxu meets new Russian Ambassador to China Igor Morgulov in Beijing.

Nov. 1, 2022: Chinese Premier Li Keqiang chairs the 21st SCO Prime Ministerial meeting.

Nov. 2, 2022: Russian Foreign Ministry issues a statement that Moscow strictly adheres to the principle of the inadmissibility of nuclear war in terms of its nuclear deterrence policy.

Nov. 15, 2022: FM Wang Yi meets Russian FM Lavrov on the sidelines of the G20 meeting in Indonesia. Wang tellsLavrov that China endorses Russia’s no nuclear pledge on Ukraine and acknowledges that Russia reiterated its position that a nuclear war was “impossible and inadmissible.” “It is a rational and responsible position from Russia.” China reportedly objects to calling Russia’s invasion of Ukraine a “war” in a joint communique.

Nov. 15, 2022: Special Representative of the Chinese Government on Korean Peninsula Affairs Liu Xiaoming meets in Beijing newly appointed Russian Ambassador to China Igor Morgulov.

Nov. 17, 2022: Assistant Foreign Minister Wu Jianghao meets in Beijing with newly-appointed Russian Ambassador to China Morgulov.

Nov. 25, 2022: Russia’s space agency Roscosmos and China National Space Administration (CNSA) sign two documents: one on bilateral space cooperation in 2023-2027 and the other on cooperation in creating a joint scientific lunar station to be completed by 2035.

Nov. 27, 2022: Chinese FM Wang Yi meets in Beijing with newly-appointed Russian Ambassador to China Morgulov.

Nov. 30, 2022: Russian and Chinese strategic bombers conduct a joint patrol over the western Pacific. Four Russian Tu-95 and two Chinese H-6K bombers fly over the Sea of Japan and the East China Sea during an eight-hour mission. A Chinese YU-20 tanker, J-16 fighter jets, Russia’s Su-30 SM, and Su-35S fighter jets escort the mission. This is the 5thtime since the two sides started in 2019 and the second time in 2022. As part of the drills, Russian bombers for the first time land in China and the Chinese bombers fly to an air base in Russia.

Dec. 5, 2022: Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin and Chinese Premier Li Keqiang jointly chair the 27th prime minister meeting via video.

Dec. 9, 2022: SCO and CIS defense ministers hold joint meeting in Moscow. Chinese Defense Minister Col. Gen. Wei Fenghe attends via video link. President Putin gives a video address, urging participants to “continue developing a constant exchange of information in defense policy within the SCO and the CIS, share experience in building national armed forces, ramping up military-technical cooperation and introducing the most advanced armaments and hardware.”

Dec. 20-21, 2022: Chairman of the United Russia party and Deputy Chairman of the Russian Security Council Dmitry Medvedev visits Beijing and hold talks with CPC chairman Xi. Medvedev delivers a message from President Putin.

Dec. 21, 2022: President Putin inaugurates via video the Kovykta gas field (1.8 trillion cm reserves) and the 800-km Kovykta-Chayanda section of the Power of Siberia gas pipeline.

Dec. 21-27, 2022: Russian and Chinese navies conduct Joint Sea-2022 naval exercises in the East China Sea. Four Russian warships join five Chinese vessels and practice mine sweeping, air defense, communication, and anti-submarine items. It is the 10th drill of this kind since 2012.

Dec. 30, 2022: Putin and Xi hold a video conference. In addition to exchange of New Year greetings, the two also discuss the Ukraine issue, including the possibility of a peace negotiation.